chapter at a glance

Even with great talents many people fail to achieve great things. A good part of the reason lies with unwillingness to work hard enough to achieve high performance. Here's what to look for in Chapter 5. Don't forget to check your learning with the Summary Questions & Answers and Self-Test in the end-of-chapter Study Guide.

WHAT IS MOTIVATION?

Motivation Defined

Types of Motivation Theories

Motivation across Cultures

WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM THE NEEDS THEORIES OF MOTIVATION?

Hierarchy of Needs Theory

ERG Theory

Acquired Needs Theory

Two-Factor Theory

WHAT IS THE EQUITY THEORY OF MOTIVATION?

Equity and Social Comparisons

Equity Theory Predictions

Equity Theory and Organizational Justice

WHAT ARE THE INSIGHTS OF THE EXPECTANCY THEORY OF MOTIVATION?

Expectancy Terms and Concepts

Expectancy Theory Predictions

Expectancy Implications and Research

WHAT IS THE GOAL-SETTING THEORY OF MOTIVATION?

Motivational Properties of Goals

Goal-Setting Guidelines

Goal Setting and the Management Process

Wall Street Journal columnist Carol Hymowitz opened an article written about successful female executives with this sentence: "Reach for the top—and don't eliminate choices too soon or worry about the myth of balance."

One of the first leaders mentioned in her article is Carol Bartz, former executive chairman of the board of the noted software firm Autodesk and the new CEO of Yahoo. In her interview with Hymowitz, Bartz points out that women often suffer from guilt, inappropriately she believes, as they pursue career tracks. In her own case she has both a demanding career and a family. And in both respects she says that she's found happiness.

"If you are comfortable with your choices, that's the definition of peace."

Andrea Jung, both chair and CEO of Avon products, agrees with Bartz that women have to work long hours and meet the challenges of multiple demands as they work their way to the top. For Jung this includes lots of international travel, overnight flights, and jet lag. She makes no bones about the fact that sacrifices are real: missed family gatherings, children's school functions, and more. But she also considers the trade-offs worthwhile, saying: "If you're comfortable with your choices, that's the definition of peace."

Nancy Peretsman is managing director and executive vice president of the investment bank Allen & Company. She laments that many young women believe they have to trade career advancement for fulfillment in their personal lives. Not so, says Peretsman, who has a top job and a family that includes teenage daughters. She says: "No one will die if you don't show up at every business meeting or every school play."

As for Hymowitz's conclusions, one stands out clearly. She finds that the lessons from women at the top of the corporate ladder come down to these: setting goals, persevering, accepting stretch assignments, obtaining broad experiences, focusing on strengths not weaknesses, and being willing to take charge of one's own career. That advice seems well voiced. It also seems appropriate for anyone, be they man or woman, seeking career and personal success in today's corporate world.

achievement requires effort

The opening voices from women at the top of the corporate ladder raise interesting issues. Among them is "motivation." The featured corporate leaders all work very hard, have high goals, and are realistic about the trade-offs between career and family. It's easy and accurate to say that they are highly motivated. But how much do we really know about motivation and the conditions under which people, ourselves included, become highly motivated to work hard ... at school, in our jobs, and in our leisure and personal pursuits?

By definition, motivation refers to the individual forces that account for the direction, level, and persistence of a person's effort expended at work. Direction refers to an individual's choice when presented with a number of possible alternatives (e.g., whether to pursue quality, quantity, or both in one's work). Level refers to the amount of effort a person puts forth (e.g., to put forth a lot or very little). Persistence refers to the length of time a person sticks with a given action (e.g., to keep trying or to give up when something proves difficult to attain).

Motivation refers to forces within an individual that account for the level, direction, and persistence of effort expended at work.

Content theories profile different needs that may motivate individual behavior.

Process theories examine the thought processes that motivate individual behavior.

There are many available theories of motivation, and they can be divided into two broad categories: content theories and process theories.[286] Theories of both types contribute to our understanding of motivation to work, but none offers a complete explanation. In studying a variety of theories, our goal is to gather useful insights that can be integrated into motivational approaches that are appropriate for different situations.

Content theories of motivation focus primarily on individual needs—that is, physiological or psychological deficiencies that we feel a compulsion to reduce or eliminate. The content theories try to explain work behaviors based on pathways to need satisfaction and the influence of blocked needs. This chapter discusses Maslow's hierarchy of needs theory, Alderfer's ERG theory, McClelland's acquired needs theory, and Herzberg's two-factor theory.

Process theories of motivation focus on the thought or cognitive processes that take place within the minds of people and that influence their behavior. Whereas a content approach may identify job security as an important individual need, a process approach would probe further to identify why the person decides to behave in certain ways relative to available rewards and work opportunities. Three process theories discussed in this chapter are equity theory, expectancy theory, and goal-setting theory.

An important caveat should be noted before examining specific motivation theories. Although motivation is a key concern in organizations everywhere, the theories are largely developed from a North American perspective. As a result, they are subject to cultural limitations and contingencies.[287] Indeed, the determinants of motivation and the best ways to deal with it are likely to vary considerably across the cultures of Asia, South America, Eastern Europe, and Africa, as well as North America. For example, an individual financial bonus might prove "motivational" as a reward in one culture, but not in another. In researching, studying, and using motivation theories we should be sensitive to cross-cultural issues. We must avoid being parochial or ethnocentric by assuming that people in all cultures are motivated by the same things in the same ways.[288]

Content theories, as noted earlier, suggest that motivation results from our attempts to satisfy important needs. They suggest that managers should be able to understand individual needs and to create work environments that respond positively to them. Each of the following theories takes a slightly different approach in addressing this challenge.

Abraham Maslow's hierarchy of needs theory, depicted in Figure 5.1, identifies five levels of individual needs. They range from self-actualization and esteem needs at the top, to social, safety, and physiological needs at the bottom.[289] The concept of a needs "hierarchy" assumes that some needs are more important than others and must be satisfied before the other needs can serve as motivators. For example, physiological needs must be satisfied before safety needs are activated; safety needs must be satisfied before social needs are activated; and so on.

Maslow's hierarchy of needs theory offers a pyramid of physiological, safety, social, esteem, and self-actualization needs.

Maslow's model is easy to understand and quite popular. But research evidence fails to support the existence of a precise five-step hierarchy of needs. If anything, the needs are more likely to operate in a flexible rather than in a strict, step-by-step sequence. Some research suggests that higher-order needs (esteem and self-actualization) tend to become more important than lower-order needs (psychological, safety, and social) as individuals move up the corporate ladder.[290] Studies also report that needs vary according to a person's career stage, the size of the organization, and even geographic location.[291] There is also no consistent evidence that the satisfaction of a need at one level decreases its importance and increases the importance of the next-higher need.[292] And findings regarding the hierarchy of needs vary when this theory is examined across cultures. For instance, social needs tend to take on higher importance in more collectivist societies, such as Mexico and Pakistan, than in individualistic ones like the United States.[293]

Clayton Alderfer's ERG theory is also based on needs, but it differs from Maslow's theory in three main respects.[294] First, ERG theory collapses Maslow's five needs categories into three: existence needs, desires for physiological and material well-being; relatedness needs, desires for satisfying interpersonal relationships; and growth needs, desires for continued personal growth and development. Second, ERG theory emphasizes a unique frustration-regression component. An already satisfied lower-level need can become activated when a higher-level need cannot be satisfied. Thus, if a person is continually frustrated in his or her attempts to satisfy growth needs, relatedness needs can again surface as key motivators. Third, unlike Maslow's theory, ERG theory contends that more than one need may be activated at the same time.

The supporting evidence for ERG theory is encouraging, even though further research is needed.[295] In particular, ERG theory's allowance for regression back to lower-level needs is a valuable contribution to our thinking. It may help to explain why in some settings, for example, worker complaints focus mainly on wages, benefits, and working conditions—things relating to existence needs. Although these needs are important, their importance may be exaggerated because the workers cannot otherwise satisfy relatedness and growth needs in their jobs. This is an example of how ERG theory offers a more flexible approach to understanding human needs than does Maslow's hierarchy.

In the late 1940s psychologist David I. McClelland and his co-workers began experimenting with the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) as a way of measuring human needs.[296] The TAT is a projective technique that asks people to view pictures and write stories about what they see. For example, McClelland showed three executives a photograph of a man looking at family photos arranged on his work desk. One executive wrote of an engineer who was daydreaming about a family outing scheduled for the next day. Another described a designer who had picked up an idea for a new gadget from remarks made by his family. The third described an engineer who was intently working on a bridge stress problem that he seemed sure to solve because of his confident look.[297]

McClelland identified themes in the TAT stories that he believed correspond to needs that are acquired over time as a result of our life experiences. Need for achievement (nAch) is the desire to do something better or more efficiently, to solve problems, or to master complex tasks. Need for affiliation (nAff) is the desire to establish and maintain friendly and warm relations with others. Need for power (nPower) is the desire to control others, to influence their behavior, or to be responsible for others.

Because each need can be linked with a set of work preferences, McClelland encouraged managers to learn how to identify the presence of nAch, nAff, and nPower in themselves and in others. Someone with a high need for achievement will prefer individual responsibilities, challenging goals, and performance feedback. Someone with a high need affiliation is drawn to interpersonal relationships and opportunities for communication. Someone with a high need for power seeks influence over others and likes attention and recognition.

Need for achievement (nAch) is the desire to do better, solve problems, or master complex tasks.

Need for affiliation (nAff) is the desire for friendly and warm relations with others.

Need for power (nPower) is the desire to control others and influence their behavior.

Since these three needs are acquired, McClelland also believed it may be possible to teach people to develop need profiles required for success in various types of jobs. His research indicated, for example, that a moderate to high need for power that is stronger than a need for affiliation is linked with success as a senior executive. The high nPower creates the willingness to exercise influence and control over others; the lower nAff allows the executive to make difficult decisions without undue worry over being disliked.[298]

Research lends considerable insight into the need for achievement in particular, and it includes some interesting applications in developing nations. For example, McClelland trained businesspeople in Kakinda, India to think, talk, and act like high achievers by having them write stories about achievement and participate in a business game that encouraged achievement. The businesspeople also met with successful entrepreneurs and learned how to set challenging goals for their own businesses. Over a two-year period following these activities, the participants from the Kakinda study engaged in activities that created twice as many new jobs as those who hadn't received the training.[299]

Frederick Herzberg took yet another approach to examining the link between individual needs and motivation. He began by asking workers to report the times they felt exceptionally good about their jobs and the times they felt exceptionally bad about them.[300] The researchers noticed that people talked about very different things when they reported feeling good or bad about their jobs. Herzberg explained these results using the two-factor theory, also known as the motivator-hygiene theory, because this theory identifies two different factors as primary causes of job satisfaction and job dissatisfaction.

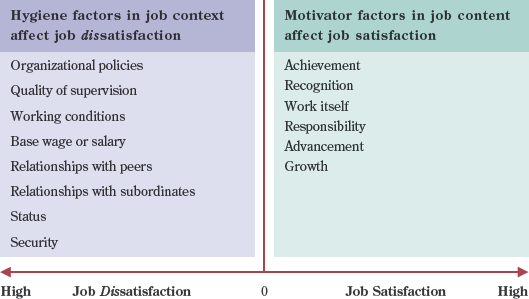

Hygiene factors are sources of job dissatisfaction, and they are associated with the job context or work setting. That is, they relate more to the environment in which people work than to the nature of the work itself. The two-factor theory suggests that job dissatisfaction results when hygiene factors are poor. But it also suggests that improving the hygiene factors will only decrease job dissatisfaction; it will not increase job satisfaction. Among the hygiene factors shown on the left in Figure 5.2, perhaps the most surprising is salary. Herzberg found that a low base salary or wage makes people dissatisfied, but that paying more does not necessarily satisfy or motivate them.

Herzberg's two-factor theory identifies job context as the source of job dissatisfaction and job content as the source of job satisfaction.

Hygiene factors in the job context are sources of job dissatisfaction.

Motivator factors, shown on the right in Figure 5.2, are sources of job satisfaction. These factors are related to job content—what people actually do in their work. They include such things as a sense of achievement, opportunities for personal growth, recognition, and responsibility. According to the two-factor theory, the presence or absence of satisfiers or motivators in people's jobs is the key link to satisfaction, motivation, and performance. When motivator factors are minimal, low job satisfaction decreases motivation and performance; when motivator factors are substantial, high job satisfaction raises motivation and performance.

Job satisfaction and job dissatisfaction are separate dimensions in the two-factor theory. Taking action to improve a hygiene factor, such as by giving pay raises or creating better physical working conditions, will not make people satisfied with their work; it will only prevent them from being dissatisfied on these matters. To improve job satisfaction, Herzberg suggests the technique of job enrichment as a way of building satisfiers into job content. This technique is given special attention in the next chapter as a job design alternative. For now, the implication is well summarized in this statement by Herzberg: "If you want people to do a good job, give them a good job to do."[301]

OB scholars have long debated the merits of the two-factor theory, with special concerns being directed at failures to confirm the theory through additional research.[302] It is criticized as being method bound, or only replicable when Herzberg's original methods are used. This is a serious criticism, since the scientific approach valued in OB requires that theories be verifiable under different research methods.[303] Yet, the distinction between hygiene and motivator factors has been a useful contribution to OB. As will be apparent in the discussions of job designs and alternative work schedules in the next chapter, the notion of two factors—job content and job context—has a practical validity that adds useful discipline to management thinking.

Motivator factors in the job content are sources of job satisfaction.

What happens when you get a grade back on a written assignment or test? How do you interpret your results, and what happens to your future motivation in the course? Such questions fall in the domain of the first process theory of motivation to be discussed here—equity theory. As applied to the workplace through the writing of J. Stacy Adams, equity theory argues that any perceived inequity becomes a motivating state of mind; in other words, people are motivated to behave in ways that restore or maintain equity in situations.[304]

Adams's equity theory posits that people will act to eliminate any felt inequity in the rewards received for their work in comparison with others.

The basic foundation of equity theory is social comparison. Think back to the earlier questions. When you receive a grade, do you try to find out what others received as well? And when you do, does the interpretation of your grade depend, in part, on how well your grade compared to those of others? Equity theory would predict that your response upon receiving a grade will be based on whether or not you perceive it as fair and equitable. Furthermore, that determination is only made after you compare your results with those received by others.

Adams argues that this logic applies equally well to the motivational consequences of any rewards that one might receive at work. Adams believes that motivation is a function of how one evaluates rewards received relative to efforts made, and as compared to the rewards received by others relative to their efforts made. A key word in this comparison is "fairness," and as you might expect, any feelings of unfairness or perceived inequity are uncomfortable. They create a state of mind we are motivated to eliminate.

Perceived inequity occurs when someone believes that the rewards received for his or her work contributions compare unfavorably to the rewards other people appear to have received for their work. The basic equity comparison can be summarized as follows:

Felt negative inequity in this equation exists when an individual feels that he or she has received relatively less than others have in proportion to work inputs. Felt positive inequity exists when an individual feels that he or she has received relatively more than others have. When either feeling exists, the theory states that people will be motivated to act in ways that remove the discomfort and restore a sense of felt equity. In the case of perceived negative inequity, for example, people are likely to respond by engaging in one or more of the following behaviors:

Change work inputs (e.g., reduce performance efforts).

Change the outcomes (rewards) received (e.g., ask for a raise).

Leave the situation (e.g., quit).

Change the comparison points (e.g., compare self to a different co-worker).

Psychologically distort the comparisons (e.g., rationalize that the inequity is only temporary and will be resolved in the future).

Take actions to change the inputs or outputs of the comparison person (e.g., get a co-worker to accept more work).

Research on equity theory indicates that people who feel they are overpaid (perceived positive inequity) are likely to try to increase the quantity or quality of their work, whereas those who feel they are underpaid (perceived negative inequity) are likely to try to decrease the quantity or quality of their work.[305] The research is most conclusive with respect to felt negative inequity. It appears that people are less comfortable when they are under-rewarded than when they are over-rewarded.

You can view the equity comparison as intervening between the allocation of rewards and the ultimate motivational impact for the recipient. That is:

A reward given by a team leader and expected to be highly motivational to a team member, for example, may or may not work as intended. Unless the reward is perceived as fair and equitable in comparison with the results for other teammates, the reward may create negative equity dynamics and work just the opposite of what the team leader expected. Equity theory reminds us that the motivational value of rewards is determined by the individual's interpretation in the context of social comparison. It is not the reward-giver's intentions that count; it is how the recipient perceives the reward that will determine actual motivational outcomes. OB Savvy 5.1 offers ideas on how people cope with such equity dynamics.

The processes associated with equity theory and its predictions about motivation are subject to cultural contingencies. The findings and predictions reported here are particularly tied to individualistic cultures in which self-interest tends to govern social comparisons. In more collectivist cultures, such as those of many Asian countries, the concern often runs more for equality than equity. This allows for solidarity with the group and helps to maintain harmony in social relationships.[306]

One of the basic elements of equity theory is the fairness with which people perceive they are being treated. This raises an issue in organizational behavior known as organizational justice—how fair and equitable people view the practices of their workplace. In ethics, the justice view of moral reasoning considers behavior to be ethical when it is fair and impartial in the treatment of people. Organizational justice notions are important in OB, and in respect to equity theory, they emerge along three dimensions.[307]

Procedural justice is the degree to which the rules and procedures specified by policies are properly followed in all cases to which they are applied. In a sexual harassment case, for example, this may mean that required formal hearings are held for every case submitted for administrative review. Distributive justice is the degree to which all people are treated the same under a policy, regardless of race, ethnicity, gender, age, or any other demographic characteristic. In a sexual harassment case, this might mean that a complaint filed by a man against a woman would receive the same consideration as one filed by a woman against a man. Interactional justice is the degree to which the people affected by a decision are treated with dignity and respect.[308] Interactional justice in a sexual harassment case, for example, may mean that both the accused and accusing parties believe they have received a complete explanation of any decision made.

Organizational justice is an issue of how fair and equitable people view workplace practices.

Procedural justice is the degree to which rules are always properly followed to implement policies.

Distributive justice is the degree to which all people are treated the same under a policy.

Interactional justice is the degree to which the people are treated with dignity and respect in decisions affecting them.

Among the many implications of equity theory, those dealing with organizational justice also must be considered. The ways in which people perceive they are being treated at work with respect to procedural, distributive, and interactional justice are likely to affect their motivation. And it is their perceptions of these justice types, often made in a context of social comparison, that create the ultimate motivational influence.

Another of the process theories of motivation is Victor Vroom's expectancy theory.[309] It posits that motivation is a result of a rational calculation—people will do what they can do when they want to do it.

Vroom's expectancy theory argues that work motivation is determined by individual beliefs regarding effort/performance relationships and work outcomes.

In expectancy theory, and as summarized in Figure 5.3, a person is motivated to the degree that he or she believes that: (1) effort will yield acceptable performance (expectancy), (2) performance will be rewarded (instrumentality), and (3) the value of the rewards is highly positive (valence). Each of the key underlying concepts or terms is defined as follows.

Expectancy is the probability assigned by an individual that work effort will be followed by a given level of achieved task performance. Expectancy would equal zero if the person felt it were impossible to achieve the given performance level; it would equal one if a person were 100 percent certain that the performance could be achieved.

Instrumentality is the probability assigned by the individual that a given level of achieved task performance will lead to various work outcomes. Instrumentality also varies from 0 to 1. Strictly speaking, Vroom's treatment of instrumentality would allow it to vary from −1 to +1. We use the probability definition here and the 0 to +1 range for pedagogical purposes; it is consistent with the instrumentality notion.

Valence is the value attached by the individual to various work outcomes. Valences form a scale from −1 (very undesirable outcome) to + 1 (very desirable outcome).

Expectancy is the probability that work effort will be followed by performance accomplishment.

Instrumentality is the probability that performance will lead to various work outcomes.

Valence is the value to the individual of various work outcomes.

Vroom posits that motivation, expectancy, instrumentality, and valence are related to one another by this equation.

| Motivation = Expectancy × Instrumentality × Valence |

You can remember this equation simply as M = E × I × V, and the multiplier effect described by the "×" signs is significant. It means that the motivational appeal of a given work path is sharply reduced whenever any one or more of these factors approaches the value of zero. Conversely, for a given reward to have a high and positive motivational impact as a work outcome, the expectancy, instrumentality, and valence associated with the reward all must be high and positive.

Suppose that a manager is wondering whether or not the prospect of earning a merit pay raise will be motivational to an employee. Expectancy theory predicts that motivation to work hard to earn the merit pay will be low if expectancy is low—a person feels that he or she cannot achieve the necessary performance level. Motivation will also be low if instrumentality is low—the person is not confident a high level of task performance will result in a high merit pay raise. Motivation will also be low if valence is low—the person places little value on a merit pay increase. Finally, motivation will be low if any combination of these exists. Thus, the multiplier effect advises managers to act to maximize expectancy, instrumentality, and valence when seeking to create high levels of work motivation. A zero at any location on the right side of the expectancy equation will result in zero motivation.

Expectancy logic argues that managers should always try to intervene actively in work situations to maximize work expectancies, instrumentalities, and valences that support organizational objectives.[310] To influence expectancies, the advice is to select people with proper abilities, train them well, support them with needed resources, and identify clear performance goals. To influence instrumentality, the advice is to clarify performance-reward relationships, and then to confirm or live up to them when rewards are actually given for performance accomplishments. To influence valences, the advice is to identify the needs that are important to each individual and then try to adjust available rewards to match these needs.

A great deal of research on expectancy theory has been conducted.[311] Even though the theory has received substantial support, specific details, such as the operation of the multiplier effect, remain subject to some question. In addition, expectancy theory has proven interesting in terms of helping to explain some apparently counterintuitive findings in cross-cultural management situations. For example, a pay raise motivated one group of Mexican workers to work fewer hours. They wanted a certain amount of money in order to enjoy things other than work, rather than just getting more money in general. A Japanese sales representative's promotion to manager of a U.S. company adversely affected his performance. His superiors did not realize that the promotion embarrassed him and distanced him from his colleagues.[312]

Some years ago a Minnesota Vikings defensive end gathered up an opponent's fumble. Then, with obvious effort and delight, he ran the ball into the wrong end zone. Clearly, the athlete did not lack motivation. Unfortunately, however, he failed to channel his energies toward the right goal. Similar problems in goal direction are found in many work settings. Goals are important aspects of motivation, and yet they often go unaddressed. Without clear goals, employees may suffer direction problems; when goals are both clear and properly set, employees may be highly motivated to move in the direction of goal accomplishment.

Goal setting is the process of developing, negotiating, and formalizing the targets or objectives that a person is responsible for accomplishing.[313] Over a number of years Edwin Locke, Gary Latham, and their associates have developed a comprehensive framework linking goals to performance. About the importance of goals and goal setting, Locke and Latham say: "Purposeful activity is the essence of living action. If the purpose is neither clear nor challenging, very little gets accomplished."[314] Research on goal setting is now quite extensive. Indeed, more research has been done on goal setting than on any other theory related to work motivation.[315] Nearly 400 studies have been conducted in several countries, including Australia, England, Germany, Japan, and the United States.[316] Although the theory has its critics, the basic precepts of goal-setting theory remain an important source of advice for managing human behavior in the work setting.[317]

Managerially speaking, the implications of research on goal setting can be summarized in the following guidelines.[318]

Difficult goals are more likely to lead to higher performance than are less difficult ones. If the goals are seen as too difficult or impossible, however, the relationship with performance no longer holds. For example, you will likely perform better as a financial services agent if you have a goal of selling 6 annuities a week than if you have a goal of selling 3. But if your goal is selling 15 annuities a week, you may consider that impossible to achieve, and your performance may well be lower than what it would be with a more realistic goal.

Specific goals are more likely to lead to higher performance than are no goals or vague or very general ones. All too often people work with very general goals such as the encouragement to "do your best." Research indicates that more specific goals, such as selling six computers a day, are much more motivational than a simple "do your best" goal.

Task feedback, or knowledge of results, is likely to motivate people toward higher performance by encouraging the setting of higher performance goals. Feedback lets people know where they stand and whether they are on course or off course in their efforts. For example, think about how eager you are to find out how well you did on an examination.

Goals are most likely to lead to higher performance when people have the abilities and the feelings of self-efficacy required to accomplish them. The individual must be able to accomplish the goals and feel confident in those abilities. To take the financial services example again, you may be able to do what is required to sell 6 annuities a week and feel confident that you can. If your goal is to sell 15, however, you may believe that your abilities are insufficient to the task, and thus you may lack the confidence to work hard enough to accomplish it.

Goals are most likely to motivate people toward higher performance when they are accepted and there is commitment to them. Participating in the goal-setting process helps build acceptance and commitment; it creates a sense of "ownership" of the goals. But goals assigned by someone else can be equally effective when the assigners are authority figures that can have an impact, and when the subordinate can actually reach the goal. According to research, assigned goals most often lead to poor performance when they are curtly or inadequately explained.

When we speak of goal setting and its motivational potential, the entire management process comes into play. Goals launch the process during planning, provide critical focal points for organizing and leading, and then facilitate controlling to make sure the desired outcomes are achieved. One approach that integrates goals across these management functions is known as management by objectives, or MBO, for short. MBO is essentially a process of joint goal setting between managers and those who report to them.[319] The process involves managers working with team members to establish performance goals and to make plans that are consistent with higher-level work unit and organizational objectives. This unlocks the motivational power of goal setting as just discussed. And when done throughout an organization, MBO also helps clarify the hierarchy of objectives as a series of well-defined means-ends chains.

Management by objectives, or MBO is a process of joint goal setting between a supervisor and a subordinate.

Figure 5.4 shows how the process allows managers to make use of goal-setting principles. The joint manager and team member discussions are designed to extend participation from the point of establishing initial goals to the point of evaluating results in terms of goal attainment. But the approach requires careful implementation. Not only must workers have the freedom to carry out the required tasks, managers should also be prepared to actively support workers' efforts to achieve the agreed-upon goals.

Although a fair amount of research based on case studies of MBO success is available, reports from scientifically rigorous studies have shown mixed results.[320] Some reported difficulties with the process include too much paperwork required to document goals and accomplishments, too much emphasis on goal-oriented rewards and punishments, as well as too much focus on top-down goals, goals that are easily stated and achieved, and individual instead of team goals. When these issues are resolved, the MBO approach has much to offer, both as a general management practice and as an application of goal-setting theory.

These learning activities from The OB Skills Workbook are suggested for Chapter 5.

Cases for Critical Thinking | Team and Experiential Exercises | Self-Assessment Portfolio |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Chapter 5 study guide: Summary Questions and Answers

What is motivation?

Motivation is an internal force that accounts for the level, direction, and persistence of effort expended at work.

Content theories—including the work of Maslow, Alderfer, McClelland, and Herzberg—focus on locating individual needs that influence behavior in the workplace.

Process theories, such as equity theory and expectancy theory, examine the thought processes that affect decisions made by workers about alternative courses of action.

Although motivation is of universal interest and importance, specific aspects of work motivation may vary from one culture to the next.

What are the needs theories of motivation?

Maslow's hierarchy of needs theory views human needs as activated in a five-step hierarchy ranging from physiological (lowest) to safety, to social, to esteem, to self-actualization (highest).

Alderfer's ERG theory collapses the five needs into three: existence, relatedness, and growth; it maintains that more than one need can be activated at a time.

McClelland's acquired needs theory focuses on the needs for achievement, affiliation, and power, and it views needs as developed over time through experience and training.

Herzberg's two-factor theory links job satisfaction to motivator factors, such as responsibility and challenge, associated with job content; it links job dissatisfaction to hygiene factors, such as pay and working conditions, associated with job context.

What is the equity theory of motivation?

Equity theory points out that social comparison takes place when people receive rewards.

Any felt inequity in social comparison will motivate people to behave in ways that restore a sense of perceived equity to the situation.

When felt inequity is negative—that is, when the individual feels unfairly treated—he or she may decide to work less hard in the future or to quit a job for other, more attractive opportunities.

Organizational justice is an issue of how fair and equitable people view workplace practices; it is described in respect to distributive, procedural, and interactive justice.

What is the expectancy theory of motivation?

Vroom's expectancy theory describes motivation as a function of an individual's beliefs concerning effort-performance relationships (expectancy), work-outcome relationships (instrumentality), and the desirability of various work outcomes (valence).

Expectancy theory states that Motivation = Expectancy × Instrumentality × Valence, and argues that managers should make each factor positive in order to ensure high levels of motivation.

What is the goal-setting theory of motivation?

Goal setting is the process of developing, negotiating, and formalizing performance targets or objectives.

Research supports predictions that the most motivational goals are challenging and specific, allow for feedback on results, and create commitment and acceptance.

The motivational impact of goals may be affected by individual difference moderators such as ability and self-efficacy.

Management by objectives is a process of joint goal setting between a supervisor and worker; it is an action framework for applying goal-setting theory in day-to-day management practice and on an organization-wide basis.

Content theories (p. 110)

Distributive justice (p. 117)

Equity theory (p. 115)

ERG theory (p. 112)

Existence needs (p. 112)

Expectancy (p. 118)

Expectancy theory (p. 118)

Growth needs (p. 112)

Hierarchy of needs theory (p. 111)

Higher-order needs (p. 112)

Hygiene factors (p. 114)

Instrumentality (p. 118)

Interactional justice (p. 117)

Lower-order needs (p. 112)

Management by objectives, or MBO (p. 123)

Motivation (p. 110)

Motivator factors (p. 115)

Need for achievement (nAch) (p. 113)

Need for affiliation (nAff) (p. 113)

Need for power (nPower) (p. 113)

Organizational justice (p. 117)

Procedural justice (p. 117)

Process theories (p. 110)

Relatedness needs (p. 112)

Two-factor theory (p. 114)

Valence (p. 118)

Motivation is defined as the level and persistence of _____________. (a) effort (b) performance (c) need satisfaction (d) performance instrumentalities

A content theory of motivation is most likely to focus on _____________. (a) organizational justice (b) instrumentalities (c) equities (d) individual needs

A process theory of motivation is most likely to focus on _____________. (a) frustration-regression (b) expectancies regarding work outcomes (c) lower-order needs (d) higher-order needs

According to McClelland, a person high in need achievement will be _____________. (a) guaranteed success in top management (b) motivated to control and influence other people (c) motivated by teamwork and collective responsibility (d) motivated by challenging but achievable goals

In Alderfer's ERG theory, the _____________ needs best correspond with Maslow's higher-order needs of esteem and self-actualization. (a) existence (b) relatedness (c) recognition (d) growth

Improvements in job satisfaction are most likely under Herzberg's two-factor theory when _____________ are improved. (a) working conditions (b) base salary (c) co-worker relationships (d) opportunities for responsibility

In Herzberg's two-factor theory _____________ factors are found in job context. (a) motivator (b) satisfier (c) hygiene (d) enrichment

In equity theory, the _____________ is a key issue. (a) social comparison of rewards and efforts (b) equality of rewards (c) equality of efforts (d) absolute value of rewards

In equity motivation theory, felt negative inequity _____________. (a) is not a motivating state (b) is a stronger motivating state than felt positive inequity (c) can be as strong a motivating state as felt positive inequity (d) does not operate as a motivating state

A manager's failure to enforce a late-to-work policy the same way for all employees is a violation of _____________ justice. (a) interactional (b) moral (c) distributive (d) procedural

In expectancy theory, _____________ is the probability that a given level of performance will lead to a particular work outcome. (a) expectancy (b) instrumentality (c) motivation (d) valence

In expectancy theory, _____________ is the perceived value of a reward. (a) expectancy (b) instrumentality (c) motivation (d) valence

Expectancy theory posits that _____________. (a) motivation is a result of rational calculation (b) work expectancies are irrelevant (c) need satisfaction is critical (d) valence is the probability that a given level of task performance will lead to various work outcomes.

Which goals tend to be more motivating? (a) challenging goals (b) easy goals (c) general goals (d) no goals

The MBO process emphasizes _____________ as a way of building worker commitment to goal accomplishment. (a) authority (b) joint goal setting (c) infrequent feedback (d) rewards

What is the frustration-regression component in Alderfer's ERG theory?

What does job enrichment mean in Herzberg's two-factor theory?

What is the difference between distributive and procedural justice?

What is the multiplier effect in expectancy theory?

While attending a business luncheon, you overhear the following conversation at a nearby table. Person A: "I'll tell you this: if you satisfy your workers' needs, they'll be productive." Person B: "I'm not so sure; if I satisfy their needs, maybe they'll be real good about coming to work but not very good about working really hard while they are there." Which person do you agree with and why?