Chapter SIX

The Soaring

Awakening, Rebellion, and the Moon

The 1960s saw the beginnings of conscientious FCC implementation of the “public interest, convenience, or necessity” provision of the Communications Act of 1934, an approach that lasted well into the 1970s. The reasons were twofold: (1) the election in 1960 of a new, young, liberal President, one whose efforts included appointing commissioners to the FCC who held proconsumer rather than proindustry philoso-phies, and (2) an environment in which large numbers of citizens rebelled against the previous decade’s oppression of freedom and expression, with a leap toward individual choice, derision of hypocrisy, and greater sensitivity to the plight of less fortunate people and the will to do something about it. One manifestation of such commitment was the growing civil rights movement. Another, later in the decade, was the women’s liberation movement.

The decade saw citizens’ increasing and forceful participation in the legal and regulatory processes of their country, in an attempt to achieve equal opportunities and a redress of grievances. The media and the FCC were not immune. The public became aware that the exploding mass media industries were rapidly gaining increased influence over the information disseminated to the public and the ideas the public formed from that information. The electronic media’s control of the nation’s political process had begun.

The decade started with a remarkable demonstration of the power of television. Vice President Richard M. Nixon and Senator John F. Kennedy were the Republican and Democratic nominees, respectively, for the Presidency. Nixon seemed a sure winner, according to the early polls, as long as nothing dramatic happened to change the course of the campaign. He was therefore opposed to participating in television debates with Kennedy; however, he felt that his refusal could be used effectively against him and, hence, agreed to several debates. The first debate, on September 26, turned the election around. The largest audience to watch a single television program up to that time, an estimated 75 million, saw a fresh, vigorous, bright Kennedy and a seemingly unshaven, tired, scowling Nixon, the latter’s gray suit fading him into the background. Kennedy had makeup and costume experts prepare his physical appearance; Nixon decided he didn’t need theatrical trappings. Those who heard the debate on radio believed that, on the issues, Nixon had won; by contrast, those who saw it on television felt that Kennedy had won. Though Nixon regained ground by the time all four debates were over, the damage had been done and Kennedy was in the lead in the polls. Politics would never again be the same: Image would replace issues in reaching the public through television, and most of the public would thereafter vote on the basis of personality rather than policy.

To preclude debates among all of the 16 bona fide Presidential candidates on the ballot in one or more states that year, Congress suspended the equal-time provisions of the Communications Act, allowing the media to restrict their debate coverage to only the two leading eligible political parties. Another innovation in TV and politics that year was the networks’ use, for the first time, of computers to predict the voting results on election day, even before the polls throughout the country had closed.

Another scandal rocked the FCC. President Eisenhower asked for the resignation of the FCC chairman, John C. Doerfer, following charges of (1) false billing of expenses and (2) accepting substantial gifts from the industry Doerfer was supposed to regulate. Increasing numbers of citizen complaints about broadcasting prompted the FCC to establish a Complaints and Compliance Division, the responsibilities of which continued, under different organizational names, into the 2000s.

Eighty-seven percent of U.S. homes had TV sets in 1960, with 440 VHF and 75 UHF stations on the air. More than 4,000 radio stations were in operation, 815 of them FM. Although sales of radio sets had doubled from 1955, only 11% of the public yet had FM receivers. Cable TV now had 650,000 subscribers—but that number was still only about 1.5% of the nation’s households.

The networks developed programming to meet the overall growth, in the process starting to take back control of programming from advertising agencies. Instead of accepting shows that the advertisers provided, networks attempted first to get rights to programs and then to sell them to sponsors. This approach gave the networks better control of their schedules as well as of individual programs.

Television program content varied. On one hand, Edward R. Murrow and Fred Friendly’s Harvest of Shame documentary on See It Now the day after Thanksgiving, with its theme, as stated by one of the farm supervisors, that “we used to own our slaves; now we just rent them,” prompted public outrage and congressional legislation to protect migrant workers from cruel exploitation and inhuman living and working conditions. CBS wasn’t the only network to deal with controversial issues. NBC’s White Paper and ABC’s Close-Up series documented and suggested humanistic solutions to problems that many people in the United States tried to pretend didn’t exist.

On the other hand, the success of a new show, The Untouchables, with its 35-share of the audience (the percentage of sets on tuned to a given program), paved the way for a copycat deluge of similarly violent programs. Within a year the nightly spewing of violence from the TV screens was causing concern among many citizen groups and in several federal government agencies—anxiety and disapproval that have not stopped since.

Fig 6.1 This FM program guide cover reveals the fine-arts image characteristic of the medium in the 1950s and early 1960s. Leopold Stokowski poses for station KHGM, “Home of Good Music.”

Courtesy Lynn Christian.

The Olympics were televised for the first time in 1960, and also for the first time a cartoon sitcom, The Flintstones, came to prime time. Whereas subsequent animated programs were only sporadically successful in prime time and for many years virtually nonexistent, in 1990 the unexpectedly high ratings of a comparable cartoon series, The Simpsons, suggested that it might again be time for prime-time animation.

GARRISON KEILLOR

WRITER, PRODUCER, PERFORMER

I went into radio because it was my dream since I was a little boy to be invisible. I went into radio because it was magical, like ventriloquism—“Learn to Throw Your Voice and Mystify Your Friends,” said the little ads for mail-order novelty stores. I went into radio because it was a novelty. I went into radio because I was broke and owed money to the University of Minnesota and they were talking about kicking me out, but I couldn’t let them do it; they were the only ones who had liked me enough to let me in. (I was writing for The New Yorker at the time, but it wasn’t aware of that.) Finally, I went into radio for love, for a tall girl with red hair and green eyes and long legs who sat behind me in American Literature. This was in October 1960, before so much happened in the world that made us skeptical, and to think that a beautiful girl was looking at the back of my head made me adventurous. So when she asked me once if I was in any activities, I said, “I’m in radio.” “Oh really,” she said, “that’s interesting.” And then I thought how bad I’d feel if she found out I was lying, so I went into radio.

Radio station WUM was two little rooms covered with green acoustic tile and a transmitter in a closet across the hall, in the basement of the women’s gymnasium, next to the squash court.

I went to a staff meeting. Men and women sat on the floor and smoked cigarettes and made sarcastic comments about the Lutheran church, older men and women in their twenties. They were so cool, they laughed exclusively through their noses, not overcommitting themselves. It was the beginning of a new decade and we were all anxious to make the break out of Midwesternism into something like atheistic nude Communist avant-garde pacifist anarchism, just go as far as we could. On the transmitter, which looked like a large meat locker, someone wrote the motto: “This Machine Destroys Small Minds.” It was an intense place. They talked about doing a major documentary about hypocrisy, and everybody else wanted to work on it. It’d be about four hours long and be finished by spring and it’d knock the props out from under everything as we knew it.

I was hoping for maybe a five-minute newscast or something, so I was surprised when the station manager, Don Olsen, asked me, “Could you, uh, do an evening show for like maybe five hours a night for, say, seven nights a week?” I said, heck yes. Everybody else would be busy on the documentary, he said, and they needed people to hold down the fort. “Maybe you could contribute to the hypocrisy thing later, by writing some stuff or something,” he said, but I didn’t care. I didn’t want to change the world; I only wanted to impress one beautiful girl, and for that I turned to glorious music written by great men with names I learned to beautifully pronounce in a voice I worked on so it didn’t sound so Midwestern, a voice that might have spent some time at Oxford, a voice whose mother may have been French. Men with names such as Gabriel Fauré, Andre Previn, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Claude Debussy, Olivier Messiaen, Johann Sebastian Bach—he was my favorite once I got the “ch” right.

Every evening, seven to midnight, sounds like a lot of work, but Beethoven alone wrote many works over an hour in length, and so did the others. All you needed was five of those puppies and your evening was complete. I learned to make my voice deeper by talking with my chin on my chest. It was a good deep solemn suave voice. It was thrilling for me, a boy from Anoka, to talk like that and to be intimately associated with greatness. Two months before, I was somebody who nobody ever invited to parties, and now I had my own show where great musicians appeared. I said, “You have just heard the Symphony No. 5 in C minor by Ludwig von Beethoven, Leonard Bernstein conducting the New York Philharmonic. Turning now to music of Johann Sebastian Bach, we hear his Unaccompanied Suite for Cello No. 1, played by Pablo Casals.” And there he was.

Radio amazed me and I hoped it would amaze her, too. After class one day, I said, “You know, I keep meaning to ask you out, Renee, but I’ve got this radio show I’ve got to do.” She said, “Yeah, I keep meaning to listen to that.” I said, “I’d sure like to know what you think of it. I really would.” She said, “Why don’t you come over and we could listen to it together?”

I played Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps over and over to impress her, and Poulenc, and Sessions, and Nuage by Delmer Gunsel, a local composer, avantgarde composers like Berio and Boulez, Ingmar Carlsson’s Four Choruses for Dying Orchestra on Themes of Soren Kierkegaard, Op. Posth. Things of that sort.

As the year spun by, one by one the rest of the staff slowly disappeared, dropped out, sunk by failing grades in courses taught by professors they could not respect. The documentary on hypocrisy never got done. I never saw anybody actually record anything for it. March came, and the middle of April, a dreary cold month, and there were only three of us left, Clifford the engineer, Jim who did “Jazz in the Afternoon,” and me. For some reason, without being aware of it at the time, I seemed to have become the station manager. But I was happy. I was on the radio, in love, talking to her, playing great music, and my grades weren’t bad either because, if I ever really needed to study, I’d just say, “We begin tonight’s program with music of Johann Sebastian Bach, his Mass in B-minor, heard in its entirety and without commercial interruption.” Almost three hours in the clear. I could run over to the library, check the reading list, sit down, get sort of an overview of the American Democratic Tradition, keep my eye on the clock, run back, and turn the record over, but even if it was stuck in the groove, nobody called up to complain. That’s how good Bach is. There’s so much there that one phrase repeated over and over just keeps showing you something else.

All spring I sat in the studio and played great music, imagining tonight would be the night she’d tune in and realize that this smooth voice was me and suddenly she’d be there! Waving, at the studio window! I’d wave her in and she’d say, “I heard your show. It’s great. I love Bach!” and I’d say, “Hey, Renee, somehow I knew you had to love Bach as much as I love Bach and I knew that someday you and I would love Bach together.”

But that evening never came. One night a guy appeared at the studio window, waving, and ran in and said, “We’re off the air!” He wore a shirt that looked like old wallpaper with eight ballpoint pens in the pocket clipped to a white plastic pocket protector: I could see he was an engineer. It was Clifford. “When did we go off the air?” I said. He said, “I’m not sure but probably sometime before Christmas. That’s when I went to California. Didn’t you ever check the transmitter?” “No,” I said, “I’m the station manager.” And he reached down and turned off the turntable.

Suddenly I understood why nobody had ever called in to complain about Le Sacre du Printemps. I had been my only listener. I had spent six months talking to myself in a voice that wasn’t even my own. If this happened to me today, it would probably kill me, but when you’re 19, you bounce back from these disasters, and I picked up the phone and called the one person I knew who could comfort me at this terrible moment in my career. “Renee,” I said, “I need to come over and see you.” “Okay,” she said. So I did.

We talked for three hours—about life, for the most part—and she was wonderful, and I wished I really was in love with her, like you might wish you could play the piano, but I’ve thought of her ever since, especially when I’m near a microphone. All these years I’ve enjoyed talking to her out there somewhere. Thank you, Renee, wherever you are.

Courtesy Garrison Keillor.

Fig 6.2 Garrison Keillor.

Photo © Cheryl Walse Bellville.

Radio programming continued to change. The last four network soaps left radio, replaced principally by news shows. KFAX, in San Francisco, became the first all-news radio station, and in Los Angeles, KABC went all-talk. More prophetic was the change-over at WABC, the ABC radio network’s pilot station in New York. Losing listeners and money, the station switched to a fast-paced, top-tune, musical ID rock-and-roll format. From a rating of 3 (the percentage of all radio homes tuned in) in its market, it jumped to a rating of 20 by the end of the decade. Stations throughout the country that followed its lead also found growing audiences. The nation’s radio stations became primarily rock-and-roll operations.

Technical innovations helped both radio and television. Tape cartridges, or “carts,” began to be used in more and more radio studios. The cordless microphone, or “mic,” came into being. Transistors made possible the development of portable radios, a boon to radio’s survival and FM’s reemergence. To stay on the air by cutting personnel costs, a number of small radio stations tried automation. Television received a boost with Emerson’s distribution of the first small, portable, battery-operated television sets, with 3-inch screens. Motorola’s development of microwave communications made it possible for TV stations to carry remotes live from almost any site. Coupled with mobile TV units—which all the networks used at the 1960 political conventions—microwave greatly enhanced the immediacy of news broadcasts.

Its implications for the future escaping most of U.S. industry, RCA struck a deal with Japan, where workers’ wages were lower than in the United States, to assemble RCA television sets in Japan from parts made in America. It seemed a good idea at the time because the savings in production costs enlarged RCA’s profits. Eventually, however, Japan began to manufacture the entire set for RCA, then made sets for other companies, and finally made sets on its own, gradually taking world leadership away from the United States in the production and distribution of television and radio equipment. But back then, U.S. industry looked on Japanese industry as something it could use for its own benefit, and even the following year, 1961, when the first Japanese-made television set, by Sony, went on sale in the United States, few people took it seriously.

1961

Within weeks after his appointment by President Kennedy to head the FCC, Newton N. Minow made his famous “vast wasteland” address at the annual convention of the NAB. Although the catchphrase was intended only as an incidental part of his speech, it became a symbol of Minow’s efforts to push television toward more and better programming in the public interest. What concerned broadcasters more specifically was the section of his speech in which Minow said, “I understand that many people feel that in the past licenses were often renewed pro forma. I say to you now: renewal will not be pro forma in the future. There is nothing permanent or sacred about a broadcast license.” The broadcast industry hadn’t heard such tough talk from regulators since the Blue Book had been issued 15 years earlier.

NEWTON MINOW

FORMER FCC CHAIRMAN

In 1961, the FCC’s brash, young, and newly appointed chairman, Newton Minow, created a stir when he delivered the following statement to attendees of NAB’s annual convention: “I invite you to sit down in front of your television set when your station goes on the air and stay without a book, magazine, newspaper, profit-and-loss sheet, or rating book to distract you—and keep your eyes glued to that set until the station signs off. I can assure you that you will observe a vast wasteland.”

Today, Minow is an attorney with a private law firm, but his famous rebuke lives on: “I recall a recent letter which came to me from a woman in a small town in the Southwest. She wanted to know what time the ‘vast wasteland’ came on.”

Fig 6.3 Newt Minow.

Courtesy Newton Minow.

One of Minow’s priorities was the development of noncommercial educational broadcasting, later on in the decade to be named public broadcasting. To facilitate the growth of this service, Minow established at the FCC an Educational Broadcasting Branch, which was to continue for almost two decades, only to be abolished, ironically, by another Democratic FCC chairman, President Jimmy Carter’s appointee, Charles Ferris. Ferris began the process of deregulation that during the subsequent Reagan administration reversed most of the Kennedy–Minow regulatory actions regarding the public interest. Minow was also responsible for arranging for a commercial frequency in New Jersey to become New York City’s first noncommercial educational television (ETV) station, in 1962. There were 51 ETV stations on the air, offering mostly cultural and instructional programming. An instructional television experiment that began in 1961, the Midwest Program on Airborne Television Instruction (MPATI), transmitted programs to class-rooms in six Midwestern states from airplanes—an early version of today’s satellite programs.

Minow attempted to strengthen the Fairness Doctrine, which was under continuous fire from the industry. His strong concern with monopolistic practices led to FCC rules that prevented networks from dictating, as they had been, even nonprime-time programming schedules for their affiliates. He was a strong advocate for the development of UHF. Two other early Kennedy FCC appointees, E. William Henry, who joined the FCC in 1961, and Kenneth Cox, who became a commissioner in 1963, were instrumental in carrying on Minow’s strong regulatory policies after Minow left the Commission in 1963, shortly before Kennedy’s assassination. During his Presidency Kennedy encouraged Minow’s efforts, reportedly telling him on one occasion, “You keep this up. This is one of the really important things.”

Kennedy used television not only for political purposes but to open up government operations to the public. He arranged for TV to cover every one of his press conferences with no restrictions. Just before Kennedy had assumed the oath of office, outgoing President Eisenhower used television to make a remarkable admission. During his Presidency he had supported McCarthyism and even jingoistic efforts of the military, the defense industry, and the CIA. Perhaps feeling he no longer needed the support of those organizations to maintain his Presidency, he used TV for his last address as President to warn the country of the dangers of the military-industrial complex.

In 1961 Westerns dominated TV programming, with such favorites as Bonanza, Gunsmoke, and Wagon Train. One could see 22 different Westerns on network television every week. Violence on television continued to concern the public, and a Senate committee headed by Senator Thomas J. Dodd began an investigation of the frequency and effects of violence on TV.

During the Kennedy administration, Ed Murrow left CBS after 25 years to become head of the United States Information Agency (USIA), where his job was to present a positive picture of the United States to the rest of the world. One of the ironies of his USIA directorship was his request to the British Broadcasting Company (BBC) not to show his own Harvest of Shame because it gave such a negative picture of America. The BBC showed it anyway, and Murrow later expressed regret for having made such a request.

FM got a boost when the FCC authorized FM stereo in 1961. Within a few years, stereo, plus the clean sound of FM, began to attract many young music listeners to the service. Paradoxically, in a move that eventually permitted FM to overtake AM as the preferred sound medium, the FCC turned down a petition for AM stereo. This action kept the older medium at a significant competitive disadvantage when stereo-phonic sound all but replaced monaural. Within the next few years, first Germany and then Japan would ensure FM’s future in the United States by exporting small, inexpensive, portable FM receivers.

1962

John Henry Faulk won his lawsuit against AWARE, Inc., and Laurence Johnson in 1962. The jury awarded Faulk $3.5 million—even more than he’d asked for. It turned out, however, that Johnson was virtually bankrupt, and so Faulk got little of the award—not enough to compensate for the fact that because he was controversial he never again worked for any network. Officially, the blacklist was now ended. Unofficially, broadcasting continued it in what was called a “graylist.”

Both the President and the First Lady made television history in 1961. President Kennedy’s ultimatum to the Soviet Union to withdraw its missiles from Cuba—his “Cuban Missile Crisis” speech—was carried on all three networks. Jacqueline Kennedy personally conducted an hour-long tour of the White House, carried by both NBC and CBS; the President joined her at the end to say good night to the viewers.

In other action related to the media, President Kennedy signed into law the All-Channel Receiver Act, which amended the Communications Act to authorize the FCC to require that, beginning in 1964, all TV sets made had to be capable of receiving both VHF and UHF. While UHF has still not achieved parity with VHF in this new millennium, this act did provide UHF with an opportunity to survive and indeed enabled many UHF stations to become very profitable.

Kennedy also signed into law the Educational Broadcasting Facilities Act, which provided, for the first time, federal grants to assist in the construction of educational television stations.

LAWRENCE LAURENT

TELEVISION CRITIC (EMERITUS), THE WASHINGTON POST

By 1962 newspapers began to notice that networks were consistently running minutes ahead of the wire services. After the 1964 California primary, in which the AP was still declaring Nelson Rockefeller the winner over Barry Goldwater, even after Goldwater had been confirmed as the winner by the networks, the wire services and three broadcasting networks met to discuss creating a cooperative vote-counting agency. Shortly afterward the National Election Service was born. NES established machinery to furnish a quick running account to all of its subscribers, thus also protecting the newspapers, all of which were subscribers to one or both wire services. The new service was activated in time to furnish its organizing members full service for the fall election of 1964.

This quotation is from Sig Mickelson’s excellent book, From Whistle Stop to Sound Bite (Praeger Publishers, New York, 1989, p. 145). Professor Mickelson is relying on a fine memory, and I would like to point out that he committed several errors. The news-gathering cooperative was first known as Network Election Service (NES) and later was called News Election Service. I know, for I was present at the creation.

The story begins on election night, 1962, at The Washington Post, where I had been the broadcasting critic for 12 years (and where I would remain for almost 20 additional years). My attention to election coverage was interrupted by a message that publisher Philip L. Graham wished to see me in the office of managing editor Alfred Friendly. I found the two of them sitting in front of a TV set, comparing the returns being displayed with the numbers fed into the Post’s teletype machines by the Associated Press and the United Press. Graham greeted me with a question: “Why are the results on television so far ahead of the wire services?”

Graham was an easygoing executive of enormous wit and great charm, but one learned quickly that his Harvard Law School training did not permit vague answers. I answered truthfully, “I don’t know.” Graham, who wore the staff worship with an easy grace, displayed his gap-toothed grin and asked, “How would you find out?”

“I would do a comparative study,” I responded, “documenting the numbers that each offered in major elections over the election night.”

“Good,” said Graham. “You get your lazy self up to New York tomorrow and start that study.” He paused and added, “And don’t spend more than $50,000.”

The following morning I was in New York, conferring with Bill Leonard, who was then running the CBS election unit. I thought CBS the best place to begin, for the simple reason that Philip Graham held the licenses to two television stations (in Washington, D.C., and in Jacksonville, Florida), both affiliated with the CBS television network. With Leonard I reviewed the vague aims of the study: Would it demonstrate that the networks were padding vote totals, as some California critics had charged? Would it show that the networks had developed new vote-gathering techniques? What were the limits a news organization ought to impose on the uses of computers? How could we improve the entire process of covering elections? Overall, I had no real idea of the ultimate use of the study I intended to do.

Leonard, who had been in television news since the end of World War II, nodded in agreement and said, almost as an afterthought, “I suppose I ought to clear this with Dick Salant?” Richard Salant, graduate of the Harvard Law School and a particular favorite of CBS President Frank Stanton, had taken over running CBS News after Sig Mickelson’s resignation. I responded to Leonard by saying, “Oh, I thought you had already done that.” I remained in Leonard’s office while he went to see Salant. Bill returned, looking unhappy. “Dick says for you to write him a letter, telling him what kind of study you intend to do and what use you intend to make of it.”

I was stunned. This was a roadblock I had never considered. No point could be made by being angry with Leonard, the messenger, so I said: “Well, that takes this matter out of my hands. I will have to call The Washington Post.” I used Leonard’s telephone to reach Alfred Friendly and recounted the morning’s happenings.

Friendly told me to go over to the wire services to set up that portion of the study, and he would have Graham talk to Salant. I spent the afternoon in the offices of the Associated Press and United Press.

Cooperation was guaranteed. Each would make available to me the entire election night file.

A telephone call from Friendly to my hotel room awakened me the next day. He sounded disgusted. “Come on home,” he said. “CBS refuses to cooperate, and that kills the project.” I responded, “Before I come back to Washington I would like to see William R. McAndrew. He’s the president of NBC News. He’s a former print journalist and may be more sympathetic toward the answers we’re trying to find.”

“Go ahead,” Friendly responded. “It can’t hurt, but I wouldn’t get my hopes too high.”

I walked through the rainy Manhattan morning to 30 Rockefeller Plaza, NBC’s headquarters, and went up to McAndrew’s office without an appointment. I dripped rain over the carpet and chairs before I took a seat near a hostile, suspicious receptionist. “Mr. McAndrew is busy, and you have no appointment. You will have to wait.” But McAndrew came to his door, spotted me immediately and insisted that I come into his office. He listened, sipping coffee, while I emphasized that I had already been turned down at CBS; that no one can limit a project or its uses before the work has been done; and that I thought both broadcasters and newspapers would benefit from such a study.

My shoes were drying, and I was warming to the task of convincing McAndrew. Yes, he and NBC might be taking a chance on the results, I argued, but McAndrew knew my work and should be certain that I wasn’t out to do a hatchet job on anyone. Besides, all of us might learn something useful.

McAndrew said, “Fine. Now, let’s bring in Julian Goodman, Elmer Lower, and Frank Jordan and see what they think.” I told my story a second time, feeling more comfortable as the audience grew bigger. Goodman was McAndrew’s chief deputy and a friend of long standing when he was NBC bureau chief in Washington. I knew Lower from his days in Washington. Frank Jordan and I were acquainted. All three agreed that the study would be a good thing.

I let out a sigh of relief, asked permission to make a collect call to Washington, and settled back while McAndrew chatted with my bosses at The Washington Post. NBC made everything available that I needed. With temporary clerical help, we made charts of vote reporting by NBC, the AP, and the UP in two-minute intervals for every senatorial and gubernatorial contest in the nation. (I made an arbitrary decision to eliminate House of Representatives elections since interest tended to be local or regional and not national.)

By the time the charts were finished, the results were clear. Each time a wire service went head to head with NBC, the broadcast network was the winner. And the reasons weren’t hard to find. First came the preparation and the organizing. Network-hired consultants had selected “key precincts” that were indicators of statewide returns. Also, networks had concentrated on elections that relied on the fast voting machines, ignoring the slower hand-marked, hand-tallied voting in some precincts. (This, almost alone, accounted for the swifter, higher totals in the California elections and put to rest charges in Los Angeles newspapers that the broadcasters were “padding” the totals.)

In some states, NBC had hired the League of Women Voters to staff every precinct and keep an open telephone line to the network. This was not expensive (NBC made a contribution to the league), and it outsped the conventional reporting methods.

In 1962, one must remember, computers were still comparatively primitive and huge. They still relied on vacuum tubes, which would be replaced within five years by the microminiature electronic circuits that grew out of transistor technology. Even in primitive form, however, the computers were a giant step in data processing. They were tailor-made for election night work. First, the computers could be programmed to prevent mistakes. For example, a computer was programmed with the exact number of registered voters in each precinct. If a total were received that was greater than the number of registered voters, the computer would reject the report. An operator would be on the telephone to the reporter, asking that he double check the data and, perhaps, see if he had transposed a digit or reversed a few numbers. Computers in those days did swift calculations in seconds and displayed the results to a television camera. (By the 1970s, the computers had tiny new components and did the same calculations in nanoseconds, meaning a billionth part of a second.)

My own roots are deep into the print culture. I had been trained in typography, schooled to worship the printed word, and had done quite well working in this technology. As a consequence, I was able to stress the handicaps inherent in publishing compared to broadcasting. Networks receive direct benefits from election night coverage. Advertisers buy election night coverage on television while often avoiding a postelection newspaper. More important, election night offers one of the rare events in which the news departments of three major networks compete directly. (Impoverished ABC News didn’t amount to much in 1962. It got its election results from the AP, and a valiant band of reporters did the very best they could.) The main point, however, is that an election night victory in the ratings or in published criticism could carry the winning news department through rough economic times. In short, in broadcasting, the winner of election night competition is rewarded.

Print, however, has a long list of opposites. Staffs are increased, overtime rates are paid, the hours are long, particularly for an East Coast newspaper with West Coast elections to cover. Newspaper editors process vote totals, write and rewrite stories of fact and interpretation. Type must be set (and it was done by a manually operated Linotype machine in 1962). Type is assembled in page form to allow matrices to be made for stereotype plates that go into the pressroom. Still later, after the entire newspaper edition is assembled, it must be delivered across a city, throughout a county, or all over a state. The hours roll by, and television has already displayed the vote totals, interpreted the results, and often sent its audience to bed before midnight. In any race with newspapers, television will always win.

I concluded a 38-page report to Graham by advising that newspapers simply would have to harness computers and that, most of all, the competition between print and electronics was wasteful and foolish. One could be proud of its speed while the other could take pride in providing a permanent record. Finally, I advised the publisher of The Washington Post that a cooperative effort would be a real benefit to both competitors and, most of all, to the voting public, which is entitled to swift, accurate, meaningful voting totals.

Graham asked me up to his office after he had finished reading the report. “That’s about what I thought you would find,” he said. (Later, I was told, Graham arranged a meeting with the Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice.) After laying out his case for intermedia cooperation, which gave no competitive advantage to any of the participants, he got a favorable answer. In the archaic, impersonal language that is so dear to this branch of Justice, the antitrust division ruled it had “no objection at this time” to the unified coverage of voting.

Philip Leslie Graham, who had so little time left in his remarkable life, was once described to me as “part prince and part Machiavelli.” He showed both traits by having the study printed privately and distributed discreetly to newspaper editors, who needed to be convinced before a cooperative could be formed. Long-held grievances had to be forgotten for editors to agree to work with broadcasters. Out of this, in 1963, came the Network Election Service, or NES, and on election night in 1964 it worked quite well. The name News Election Service was adopted two years later.

Alfred Friendly, who rode herd on NES after Mr. Graham’s death, told me several times that the study I did was vital to Mr. Graham’s campaign of breaking down print resistance to the cooperative. He would add that the study would be remembered “as probably the most important thing you have ever done.”

So, uh, pardon me, Mr. Mickelson, but I do have a different story about the formation of NES for the 1964 election and all the elections that have followed. I like my version better, too, for the simple reason that I lived it.

Courtesy Lawrence Laurent.

Fig 6.4 Lawrence Laurent worked at The Washington Post for more than 30 years, covering television for 28 of those years. He retired from the Post in 1982 and was formerly vice president/communication for the Association of Independent Television Stations. He has taught broadcasting courses at four major universities and is also editor in residence at the Broadcast Pioneers Library.

Photo by Anna Ng, Washington, D.C. Courtesy Lawrence Laurent.

In combining his interests in space and in telecommunications, Kennedy pushed for enactment of the Communications Satellite Act of 1962. It was passed and signed just a month after the launch of the United States’ first communications satellite, Telstar I, which debuted with demonstration programs between the United States and Europe. Although it would be many years before satellites were used for network transmissions across the United States, the Soviet Union in 1962 announced plans to use four Sputnik satellites for interconnection in its territories. The Communications Satellite Act of 1962 authorized a Communications Satellite Corporation (COMSAT, established in 1963) to coordinate and represent all U.S. telecommunications satellite operations.

The advances in satellite telecommunications opportunely occurred at the time that a new guru of communications, the Canadian professor Marshall McLuhan, began to have a worldwide impact on thinking in the field, including his concept that, because of electronic communications, “time has ceased, space has vanished … [and] we now live in a global village.” His theory that “The medium is the message” would become both a pro- and an antitelevision slogan.

Perhaps the most dramatic proof of the world simultaneously expanding and getting smaller was the televising in 1962 of astronaut John Glenn’s earth orbit in a space capsule, an event seen by some 135 million viewers.

Ninety percent of U.S. homes now had TV sets. What network shows were they watching? The top-rated program in 1962 was The Beverly Hillbillies. Number two was Candid Camera. A notable premiere was Johnny Carson’s taking over from Jack Paar as host of NBC’s The Tonight Show, a job Carson held for 30 years, until 1992. A notable special was Barbara Walter’s first major assignment for The Today Show, Jacqueline Kennedy’s goodwill tour of India.

FM development got another boost from the FCC in 1962 when the commission put a freeze on new AM stations. Broadcasting magazine’s headline read, “For Radio, Birth Control Begins at 40.” Many applicants who wanted new radio stations reluctantly switched to FM, little knowing at the time how fortunate a move that was.

1963

On November 22, 1963, President Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, Texas. Television was the principal news source of the tragedy. Americans stayed glued to their sets for four days and watched with a mixture of horror and unbelieving fascination as Lee Harvey Oswald, the accused killer of Kennedy, was murdered on the television screen right before their eyes by Jack Ruby, in a police station, before Oswald could be questioned about the assassination.

Earlier that year Newton Minow gave his final speech to the NAB convention, stating, “You need to do more than feed our minds. Broadcasting must also nourish the spirit. We need entertainment which helps us grow in compassion and understanding. Certainly make us laugh; but also help us comprehend. Of course, sing us to sleep; but also awaken us to the awesome dangers of our time. Surely, divert us with mysteries; but also help us to unlock the mysteries of our universe.”

Fig 6.5 Newspaper headline reporting Kennedy assassination.

Courtesy of Smithsonian Institution.

When Minow left the FCC, Kennedy appointed as chair Commissioner E. William Henry, who carried on the administration’s public interest philosophy. One of his initial efforts, to restrict the amount of commercial time on television—which was exceeding even the limits suggested in the NAB’s own code—was frustrated when the House passed a bill forbidding the FCC from doing so. The FCC withdrew its proposal.

Television news expanded. Following a Roper poll that showed television to be the principal source of news for the U.S. public, the networks extended their evening news broadcasts from 15 to 30 minutes. ABC strengthened its competition with CBS and NBC by hiring Elmer Lower to head its news division. Television news helped move the country closer to civil rights legislation when in August it televised the March on Washington, in which the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech.

Sports made news, too, with the first use of the instant replay (in the Army–Navy football game). Before long, the technique was a standard feature in TV coverage of every athletic event.

Fig 6.6 Newspaper account of the electronic media’s response to the assassination of President Kennedy.

Courtesy of Smithsonian Institution.

Then as now, ratings drove broadcasting. Concern about the validity of ratings led to a congressional study, and the House Commerce Committee reported that several rating companies were providing inaccurate information. Thereafter a closer eye was kept on rating systems, though they continued to be the arbiter of all programming.

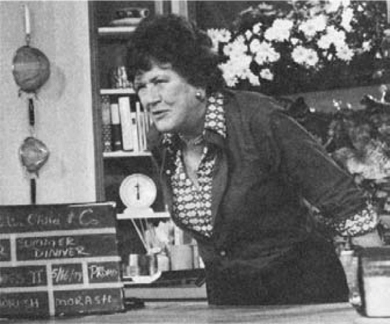

JULIA CHILD

CHEF AND TELEVISION HOST

Timing seemed to be a key factor in the success of my television show. World War II was over, air travel to Europe was suddenly affordable and accessible to the general public, the Kennedys were in the White House with a famous French chef, and European (particularly French) foods were very popular. I believe my informal style made this fancy upper-class cuisine seem less complicated. Since errors were not edited out of the programs, my shows had a credibility which provided viewers with a sense of identification.

Almost 10 hours of preparation and rehearsal went into each taped show. For most of the programs, recipes needed to be prepared several times, each one done to a particular point of completion so that the item was able to be used for illustration during the various stages of assembly. When expensive items such as suckling pig were used, the dish was auctioned off and the proceeds went to public television station WGBH; otherwise, the hungry television crew feasted on the day’s taping results.

The early shows (circa 1963–1964) were filmed in the demonstration kitchen of a public utilities company. These black-and-white shows were filmed by two stationary cameras; and because television audiences wanted things to be literal, I was not able to skip around—I needed to methodically proceed step by step from the beginning to the end. This made the show seem very long. The later shows, filmed in color, were done with addition of a handheld camera. They were edited to show a series of short segments rather than the whole process in its entirety.

Fig 6.7 Julia Child.

Courtesy Julia Child Productions, Inc.

1964

Politics—party and public—interacted strongly with broadcasting in 1964. The election campaign between President Lyndon B. Johnson, who as Vice President had succeeded Kennedy, and Republican Senator Barry Goldwater introduced the kinds of negative television spots that would later dominate U.S. elections. So strong was one spot implying that Goldwater would start an atomic war that the Democrats voluntarily withdrew it. At the same time, both parties experimented with subtle ads designed to affect the viewer psychologically and to capitalize on the experiences of previous campaigns via commercials stressing personalities and biographical sketches rather than issues. Politicians were more sensitive than ever to the power of television, and where previously TV crews had full and free access to convention activities, the Goldwater contingent tried to maintain its control of the Republican Convention by controlling the movements of reporters. In one dramatic incident, NBC’s John Chancellor was arrested, on camera, by the Goldwater forces for crossing into a forbidden area. As he was being dragged away, Chancellor signed off with “This is John Chancellor, somewhere in custody.”

A public interest group, the Office of Communications of the United Church of Christ (UCC), monitored broadcast stations’ services, especially in relation to the growing civil rights movement. Under its director, Everett Parker, the UCC Office of Communications investigated the programming and employment practices of WLBT in Jackson, Mississippi. It found the station racist in both respects and petitioned the FCC not to renew WLBT’s license. The FCC renewed it anyway, rejecting the UCC’s request for standing in the matter. In dissenting opinions, FCC Chairman Henry and Commissioner Cox insisted on the right of the public to participate in the FCC’s licensing and renewal process. The federal district court overturned the FCC’s action in 1965 and ordered WLBT’s license revoked. The court’s decision stated: “After nearly five decades of operation the broadcast industry does not seem to have grasped the simple fact that a broadcast license is a public trust subject to termination for breach of duty.”

In 1964 the FCC issued a Fairness Doctrine Primer, which not only explained how stations could implement the Fairness Doctrine but reaffirmed their obligation to do so. Coincidentally in 1964, on radio station WGCB in Red Lion, Pennsylvania, a right-wing minister, Billy James Hargis, made a personal attack on the loyalty of Fred Cook, who had written a book critical of the Republican Presidential candidate, Barry Goldwater. Cook asked for free time to reply, under the Fairness Doctrine. WGCB refused but offered to sell him time. Cook complained to the FCC, which ordered the station to comply. The station continued to refuse, and the case wound up in the Supreme Court, which five years later, in 1969, issued its landmark Red Lion decision, upholding the Fairness Doctrine and the “scarcity principle” that justified government regulation of broadcasting. (The “scarcity principle” maintains that because there are a limited number of frequencies, the airwaves belong to the public and must therefore be operated in the public interest, under an agency established by the public’s representatives.)

Other FCC actions in 1964 included hearings on payola and plugola and the establishment of fees for filling applications for licenses. Another FCC action had a long-term effect on FM. The commission, believing that FM was now ready to survive on its own, eliminated some AM-FM program duplication, forcing FM stations to develop their own programming at least 50% of the time—a move that broadcasters protested but that we now know was in FM’s best interest.

Fig 6.8 The number of radio stations programming exclusively to blacks grew in the 1950s and 1960s.

Courtesy Rick Wright.

At another federal office an event occurred that would in a few years have a significant impact on broadcast advertising: The surgeon general, who in 1956 had first warned the public about the dangers of smoking, issued the now-famous Report on Smoking.

One thousand cable systems were in operation in 1964. Fred Friendly became president of CBS News. Cassette recorders became standard equipment in radio stations. While Hello, Dolly was a national hit, rock grew as the music of the Beatles began to dominate the airwaves. The first movie especially produced for TV, The Killers, was made, starring Hollywood actor Ronald Reagan. The movie never reached the air, however—it was considered too violent.

TV’s revealing eye saw some results from its handiwork. The Civil Rights Act was passed and the Reverend King received the Nobel Peace Prize. TV would soon turn that eye on another matter that would galvanize public action: the United States’ participation in the war in Vietnam.

1965

Surveys showed that color TV programs resulted in increased viewing and greater attention to commercials, and in 1965 all the networks were now broadcasting pre-dominantly in color. Color film was being used in news programs. Among the news programs that were of most interest to Americans were those with reports from Vietnam. The networks expanded their coverage as U.S. forces expanded their participation in the conflict. Seeing the horrors of war and the body bags being carried virtually across their living rooms, more and more Americans, especially college students, began to rebel against their government’s military involvement in Southeast Asia. Vietnam became not only an issue in campus discussions but an important theme in the folk music that captured the attention of the 1960s generation. Anger and protests grew as television began to include U.S. atrocities in its reports. One such report in 1965 that had a profound effect on many Americans was news correspondent Morley Safer’s coverage of U.S. troops flicking their cigarette lighters and burning down a village of 120 huts because some of its residents had reportedly helped the Vietcong.

The Vietnam War and the continued hardening of the Cold War with the Soviet Union gave rise to a number of spy series on television. Two of the most popular were Mission: Impossible and I Spy, the latter breaking new ground in casting by costarring in an otherwise white cast a young African-American performer named Bill Cosby. Even comedy got into the TV spy act with Get Smart.

RICK SKLAR

THE LATE RICK SKLAR WAS PROGRAMMER, WABC, NEW YORK, AND HEAD OF SKLAR COMMUNICATIONS

When I began to program WABC in 1962, it was the fourth Top Forty station in the market behind WMCA, WMGM, and WINS. Researching retail record sales, I noted that the top three songs sold more than twice as many copies as the next dozen, and below the top 24 hits, sales were scattered. Abandoning the 77 record playlist I had inherited from previous programmers and consultants, I cut the airplay list to an unheard of 18 to 24 singles per week (depending on what was selling), alternating with hits of the past from our existing library of the Top 100 rock-and-roll songs from 1954 to 1961. The top three songs were put on fast repeat cycles controlled by industrial timing clocks that activated PLAY THIS SONG NEXT lights in the studio. The number-one song was played every 60 minutes, number two every 75 minutes, and number three every 90 minutes. Every other song was from the Top 14 or a recurrent (recent hit).

To be certain listeners would report WABC and the time they heard it to the rating companies, I put the Top 14 songs on tape cartridges that were tagged with jingles that sung the call letters followed by a time chime to cue the disc jockey to give the time. The station was positioned as the home of “music power.” The strategy worked. One by one WABC’s competitors switched to another format. By the late 1960s WABC had a weekly reported audience of 6 million listeners, more than twice the circulation of the next largest station in America. In a market with over four dozen radio stations, WABC’s share was often over 20%. On a typical Saturday night, more than one in every four radios was tuned to our “Cousin Brucie” show.

Fig 6.9 Rick Sklar with surrealist painter Salvador Dali, who served as the judge of a 1964 WABC contest.

Courtesy Rick Sklar.

At the FCC, the Kennedy legacy continued, with Chairman Henry getting the Commission to adopt public interest standards and service to the community as significant factors in judging to whom to award licenses in comparative hearings (those in which there were two or more applicants for the same frequency or channel). The FCC gave satellite communications further encouragement by autho-rizing COMSAT to operate commercial facilities.

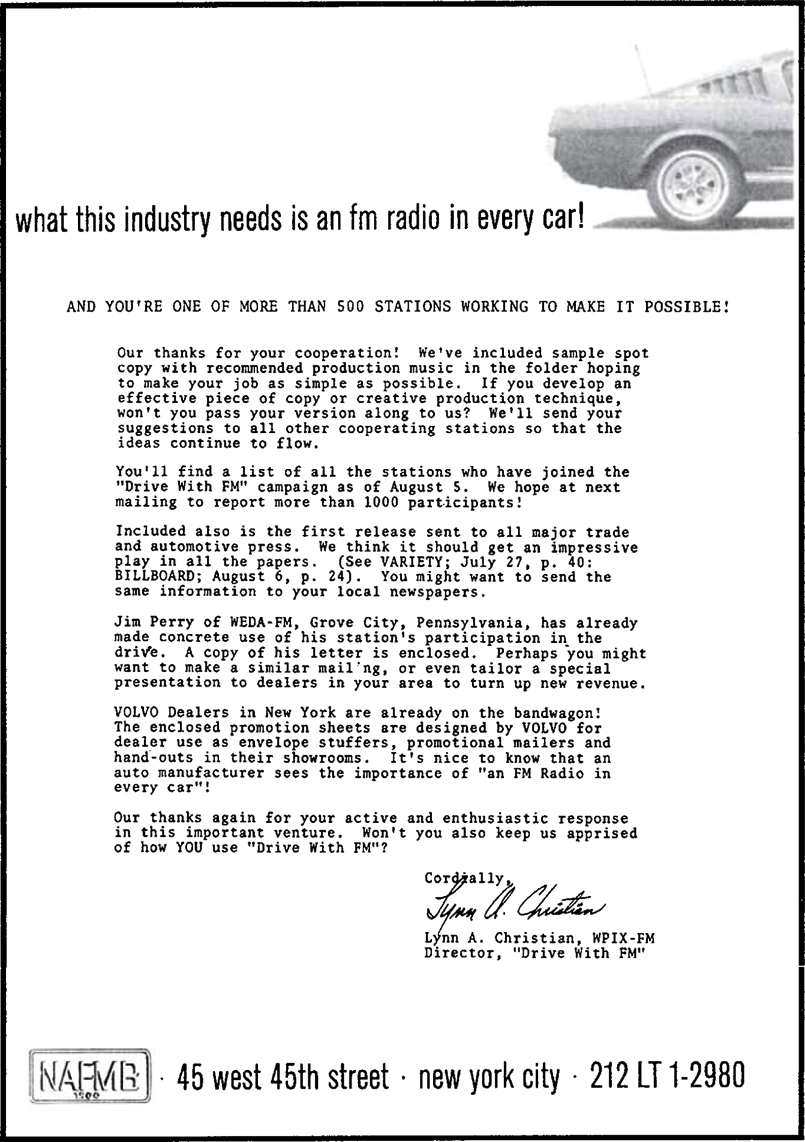

Fig 6.10 The National Association of FM Broadcasters pushed for parity with AM throughout the 1950s and 1960s. An FM receiver in every car was a primary goal.

Courtesy Lynn Christian.

The industry was in good shape financially and statistically in 1965. More than 30 million radio sets were sold that year, about a fourth of them with FM. Almost 99% of all homes and 80% of automobiles had radios. Television was now in 93% of U.S. households. Four thousand radio stations were on the air, some 1,300 of them FM. Two hundred and fifty noncommercial educational FM stations were in operation. Five hundred and seventy commercial TV stations and 100 noncommercial educational TV stations were operating. In fact, the rapid growth and importance of educational television prompted efforts to build it into a system that could be a national alternative to commercial television. To study and determine such options, the Carnegie Commission on Educational Television was established.

But two rivals to broadcasting loomed large, one with its foot already in the door and the other on the horizon. The number of households with cable television had doubled in five years and now exceeded 1.3 million, served by more than 1,300 community cable systems. The National Cable Television Association (NCTA) made its presence known when it hired as its president a former FCC chair, Frederick W. Ford. The competition on the horizon came from the Far East, as the first videotape recorders (the VTR, later the VCR), the Sony Videocorders, which sold for $995 with a 9-inch receiver, came into U.S. homes.

Other horizons visually came closer in 1965. The previous year an international conference had established INTELSAT, a global satellite communications system. On June 28, 1965, it was inaugurated with INTELSAT I, called Early Bird, transmitting across the Atlantic Ocean. Not long after that, one of the authors of this book was invited to a gala event where, on a giant screen in Washington’s Mayflower Hotel ballroom, he saw another miracle of the new satellite communications age: the first television transmission between Japan and the United States. For international telecommunications, it seemed that not even the sky was the limit.

1966

The war in Vietnam not only was a subject for television news but directly affected the operations of television in 1966. The networks continued to refuse to be critical of U.S. involvement, and sometimes they even distorted coverage to avoid stimulating negative public concern or embarrassing the administration. To do so at the time would have been considered controversial and, to some, even un-American. As Variety, the industry newspaper, finally put it, the networks were guilty of “no guts journalism.” So many voters were outraged, however, that in early 1966 the Senate began hearings on Vietnam. After initial coverage of the hearings, CBS abruptly stopped and substituted reruns of I Love Lucy and The Real McCoys. The CBS News president, Fred Friendly—one of the few news executives who displayed consistent integrity as well as courage—resigned in protest.

By the following year, antiwar protests had spread throughout the country, and network news programs were no longer able to ignore the demonstrations and marches by millions of Americans. Broadcasting provided more and more coverage, and finally individual journalists and news teams began to probe for the truth of what was happening. Their continuing efforts for honest coverage through succeeding years contributed to the government’s eventually ending the war. It was television’s stories on Vietnam and the public protests that reportedly persuaded President Lyndon Johnson not to run for another term. One account alleges that after he saw Walter Cronkite criticizing his military policy in Vietnam, Johnson decided that if Cronkite opposed him, then the average American couldn’t be far behind and he had lost his base of support.

Fig 6.11 Network coverage of the Vietnam War was extensive and had a profound effect on viewers.

Courtesy Irving Fang.

Citizen sensibility and outspoken action affected television programming directly. After 15 years on CBS television, the most recent ones as a variety program rather than in its original sitcom form, Amos ’n’ Andy could not survive the civil rights movement of the 1960s, and public antipathy to its stereotyping and alleged racism forced it off the air for good. “People power” was reflected in other ways as well. A highly innovative show that made its debut in 1965 was the science fiction adventure series Star Trek. It bombed in the ratings, consistently finishing near the back of the prime-time pack, never higher than number 52. There was no way it could survive in bottom-line broadcasting. But a vociferous letter-writing cult developed around the show’s essentially antiwar, prohumanistic story lines, reflecting the mood of much of the country. Accordingly, the series was kept on the air for three years, eventually spawning a series of theatrical movies, a new Star Trek: The Next Generation TV series—which did better commercially than the first one—followed by more spin-off series and frequent syndicated repeats of the original one. Captain Kirk, Mr. Spock, and other characters remained household words through the remainder of the century, as did annual conventions of “Trekkies.”

Fig 6.12 Network TV struck pay dirt in the mid-1960s with an adaptation of the comic strip favorite Batman. The show starred Adam West and Burt Ward.

Courtesy Artist’s Proof, Alexandria, Virginia.

The so-called ’60s generation was represented on the FCC as well. Appointed in 1966 by President Johnson, Commissioner Nicholas Johnson (no relation) vigorously and unabashedly symbolized the public interest—putting the needs of the consumer above the profits of the industry. For the next seven years, to the end of his term, Johnson would push for public interest rules and regulations that angered many broadcasters and annoyed his more conservative colleagues.

ANN LORING

ACTRESS AND WRITER

Much maligned, too often ridiculed, soap operas have long been the butt of the TV critics … a reputation they do not deserve.

I have worked in soaps from the time they were shot in black and white, and “live,” and little old men were careless with the prompting cards, when dinosaurs were nibbling the last green leaves from the trees, until ultimately I completed a 14-year leading role on Love of Life. This history, although it does inescapably “date” me, nevertheless does afford my hoary soul a maven’s credibility.

Ergo the following statements:

a. Probably the toughest acting job that exists (and I have known them all … theater, film, radio) is playing a major role in a daytime drama, as they are now euphemistically called. Absolutely true!

Imagine committing 40 to 50 pages of dialogue to memory night after night, then struggling exhausted the next morning to face cold coffee, a minuscule three- to four-hour rehearsal, always digging deep into the recesses of your brain to find the words … oh, those words … then finally facing the ultimate terror: the invisible audience of some 26 million viewers ready to judge your performance for its emotional honesty and truth, developed within these bare bones of time.

Even more distressing, imaging being judged by critics as though one had had the luxury of a week’s rehearsal or more, such as in extended prime-time shows. A consummation devoutly to be wished! I reiterate, it is the most taxing acting job of all, given these incredible circumstances.

b. My second statement bespeaks the courage of the various production staffs. Long before prime time dared, the soaps were already beginning to deal with such sensitive topics as abortion, mental illness, drug addiction, and teenage suicide. Soaps dared to make touch-and-go landings on the “untouchable” runways of general television fare.

Of course, the interplay of relationships: the unrequited love, jealousies, innumerable pregnancies, dalliances, spouse-stealing and spouse-switching and the consequent villainies were, and will continue to be, the thrust of most story lines.

But credit them, the soaps dared! They were the brave front, the very first to breach the ever-threatening enemy lines of censorship.

There is so much more to say had I but time and space. It is enough to remind one that soaps have molded taste, fashion, even behavior. The viewer, in a way that is almost beyond understanding, seems to identify and bond with his favorite character so powerfully, with such seriousness, that upon occasion he is unable to distinguish between his own life’s reality and what appears on the screen.

Even after all these years, the influence of the soaps remains startling to me. Perhaps the strength of this influence is best illustrated by the following example: Some years ago, in our story line, a mature woman was in a hospital dying of a rare disease. It was the decision that this character would die after several months of suffering her illness. During this sequence, the producer received a letter from a doctor in a nearby New York hospital, who wrote that he was treating a patient ill with this same rare disease. His patient, he told us, unfailingly watched our show each day and reacted in precise parallel to the condition of the screen character. Knowing this, the doctor pleaded with the producer to be sure to keep the character alive—for surely if she were to die, he would certainly lose his patient.

Needless to say, a conference was called, [and] the story line rewritten so that the character began to grow better in a daily sequence of improvement.

One morning, a month later, a Jeroboam of champagne arrived at the studio. With it came a touching thank-you note. The real patient was rallying and the doctor would forevermore be grateful.

Need I say more?

Courtesy Ann Loring.

Another Lyndon Johnson appointment was also a surprise but not at all controversial. When FCC Chairman Henry resigned in 1966, the President, instead of naming a Democrat to succeed him, named a sitting commissioner and a former chair, Rosel H. Hyde, a moderate Republican who had started his career with the old Federal Radio Commission. Because much of Lyndon Johnson’s personal fortune was based on broadcast holdings, some believed he was attempting to avoid charges of conflict of interest that might have been leveled had he appointed someone from his own party, politically beholden to him. Hyde kept the commission on an even keel for several years, leaving only when the next President, Richard M. Nixon, appointed his own chair.

Spy and war films were popular on TV and, to fill the “software” gap, NBC started to produce its own made-for-TV movies. ABC went it one better and paid millions to present the first blockbuster movie in prime time, The Bridge on the River Kwai. This action started a trend that still continues.

ABC, in third place and hurting financially, attempted to merge with International Telephone and Telegraph (IT&T). This arrangement would have provided the network with a needed infusion of money and created a new conglomerate with expanded media power. Although the FCC approved the merger, the Department of Justice fought it and the following year it was canceled. An attempt to establish a fourth commercial network failed, too. The Overmyer Network was established in 1966, became the United Network, and went on the air in 1967 with programs broadcast on 125 stations; a lack of advertisers caused it to fold in a month. Though regional and specialized networks (such as sports) were able to make it, another national network didn’t come on the scene again for 20 years. Then, with the huge resources of its founder, Rupert Murdoch, to back it, the Fox network not only survived but began to grow.

Cable continued to expand, with national corporations such as GE, Time, Inc., and various regional telephone companies entering the field. The FCC, deciding it was time to assert strong jurisdiction over cable, mandated that cable systems carry all local broadcast stations and limit importation of distant signals. Meanwhile, the commission closely monitored and occasionally checked the medium’s growth in major metropolitan markets.

In addition, that other future competition to broadcasting, still just a gleam, made a little headway as the price of VTRs came down to about $400.

1967

The FCC, spurred by Commissioners Johnson and Cox and responding to the public’s assertion of its rights, issued a number of strong regulatory actions in 1967. Among them were rules requiring Fairness Doctrine implementation of time to answer personal attacks on any individual (the Red Lion case, still not decided by the Supreme Court), banning station identifications that misled the audience on the station’s city of location, and—one of the most controversial rulings in the history of broadcast regulation—applying the Fairness Doctrine to cigarette advertising. Petitioned by John F. Banzhaf III, an attorney and professor of law, and relying on the findings of the surgeon general’s office on smoking and health, the FCC ruled that stations carrying cigarette commercials had to present antismoking viewpoints or offer time to antismoking organizations. Despite vehement industry protests and lawsuits, the FCC had the backing of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and other government offices, and the courts found the FCC action to be constitutional. It was this ruling that led Congress, a few years later, to ban all cigarette advertising on television and radio, a ban that went into effect on January 2, 1971. Why January 2, instead of the more logical January 1? It gave the television industry and cigarette manufacturers a final huge audience to whom to sell their wares: those watching the January 1 football bowl games.

Cigarette Advertising’s Last Hurrah

Following the Surgeon General’s 1962 report confirming the deleterious effect of tobacco, mild notices were placed on these products. Antismoking groups sought to get these warnings on the air, with limited success. Broadcasters that complied often placed these public service announcements (PSAs) in the wee hours of the morning. Action on Smoking and Health (ASH), the group guided by Attorney Banzhaf, appealed to the FCC to invoke the Fairness Doctrine, eventually seeking a “fair” balance since there were no tobacco commercials airing at 2:00 a.m., and a 3:1 ratio between tobacco ads and antismoking spots. To their surprise, and without much further deliberation, the FCC consented. In effect, this meant the tobacco companies would be subsidizing the opposition; the more ads they ran, the more anti-smoking PSAs aired. When the idea of a ban on smoking ads in broadcasting surfaced, the tobacco companies vehemently resisted.

However, in 1968, the Federal Trade Commission indicated it might seek to prohibit all tobacco ads in other media and venues. In an effort to prevent the loss of all advertising, the cigarette companies opted to move out of the then high-profile radio and TV ads. The industry acquiesced to the broadcasting embargo on the ads, and in 1969, Congress passed the ban, which took effect on January 2, 1971 (the cigarette and broadcast companies pressured the FCC to allow the last ads to run during the New Year’s Day football games). A few minutes before midnight, January 1, 1971, on NBC’s Tonight Show, Virginia Slims ran the final cigarette commercial ever on television.

In cable, two companies were formed for the express purpose of providing regular programming to cable systems, going beyond simply carrying off-the-air broadcast stations. In radio, ABC was authorized to establish four news networks, an innovative approach to providing different kinds of news to different kinds of audiences. A dozen years later, other radio networks would follow suit, and a trend of multiple, short-form (as little as one program or one program series) and long-form (a continuous block of time, similar to the old radio structure) offerings of various specialized formats to affiliates developed. This scheme helped radio networks to survive and grow.

The rebellious nature of much of the country was reflected in radio by what was to become known as the underground rock format. Tom “Big Daddy” Donahue, a former disciple of “more music king” Bill Drake, inaugurated underground radio’s precursor, progressive radio, at KMPX in San Francisco. While vacationing at home, Donahue arrived at the conclusion that only one or at best two cuts on any hit album were getting airplay and that the remaining cuts were being ignored. This realization led him to implement an album cut–intensive format at a time when AM Top 40 was the reigning monarch of the airwaves. Several months after Donahue’s programming innovation, Boston’s WBCN-FM initiated a free-form (anything goes) progressive format. Soon there were dozens of such stations across the country.

Owing in part to their nonconformist image, derived from the unorthodox mix of music and announcers who often sounded sedated—what one observer referred to as “those voices from the purple haze” (a reference to a popular rock song of the period)—many of these stations became part of the much-ballyhooed counterculture movement. The term underground, with its clandestine and subversive connotations, was ascribed to stations that gave the impression (if nothing more) of being outside the mainstream of American thinking on such issues as war, sex, and drugs. The so-called underground stations—a phrase that prompted a snicker from the leader of the Black Panthers, Eldridge Cleaver, who thought it an absurdly inappropriate name when such stations could readily be tuned in on any radio receiver, from the White House to Shaker Heights—were also later referred to as “acid rockers” because of their heavy emphasis on music associated with the psychedelic drug movement. The climate of social unrest that existed, at a time when rock music was becoming more diffused and a substantial segment of the radio audience was disenchanted with the predominance of the highly formulaic Top 40 sound, gave real impetus to the album rock format.

In the meantime, educators had convinced both President Johnson and Congress that it was time for the establishment of an educational television network. The congressional plan was based on the Carnegie Commission’s report, Public Television: A Program for Action. After many months of lobbying, radio was included, and the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967 was passed. Its principal provision was to establish the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), which, with federal funding and an independent board of directors—somewhat along the lines of the BBC—was to set up one or more national systems of public television and public radio. Within a few years CPB had created, for television, the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) and, for radio, National Public Radio (NPR). Whether President Johnson’s key role in getting the legislation passed was for political or educational reasons—or both—has been debated by public broadcasting historians. One of the authors of this book, who was involved in the Public Broadcasting Act legislation, was at the bill-signing ceremony at the White House and chatted briefly with the President about his role and the fact that inasmuch as the first public television station was KUHT in Texas, it was appropriate that a President from Texas should be responsible for this next historical step.

Outlandish Sitcoms Follow TV’s Golden Age

The appellation of television’s Golden Age refers to the abundance of mostly live original and classical dramas that dominated prime time in the 1950s, frequently with a lone sponsor who insisted they steer clear of socially and politically controversial themes. By the close of the decade critics began ruminating that these idealistic morality tales were becoming stale and repetitious. Additionally, television was spreading from its East Coast, more cosmopolitan, base to the rest of the country. Early in the 1960s, as the nation began to experience the societal upheavals that would define the decade, the medium turned to bizarre fantasy sitcoms marked by the likes of talking horses and cars, genies, benign witches, flying nuns, friendly ghouls, millionaire hillbillies, and the introduction of prime-time animation. What prompted this switch from serious, albeit narrowly prescribed, dramas is not clear, but three factors may have contributed: (1) major Hollywood studios became more involved with television production and its facilities allowed for more audacious plots; (2) a perceived need to appeal to a growing, more heterogeneous mass audience; (3) and a yearning to evade reality, assassinations, the violent repression of civil rights marches, and a growingly unpopular and endless war.

1968

The year 1968 was a high-water mark of protest, of going underground to fight the establishment, of trying to make changes in the structure of the country. There were underground newspapers, underground magazines, and underground radio stations. People fought not only against the war abroad but against poverty and discrimination at home. When they did so openly, they suffered, sometimes by harassment and beatings and sometimes worse, as in the government’s predawn raid in 1969 of a Chicago apartment where the leaders of the Black Panthers were sleeping, killing two of them in their beds. Blood, death, and tears galvanized America, especially its youth.

Television covered student demonstrations on college and university campuses all over the country. Urban demonstrations became violent. “Revolts,” some called them; others said “riots.” “Burn, baby, burn!” was a battle cry heard frequently on TV news, as desperate, underprivileged people, facing hopeless poverty and racism, futilely torched and rioted.

Not only were militant protesters attacked, but two mainstream leaders, the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., and Senator Robert F. Kennedy, were assassinated that year. The latter happened virtually in our living rooms, on TV, on Presidential primary day in California. Television also showed us, live, the police violence against protesters at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, shocking America just as the police violence against protesting civil rights marchers in the South had done only a few years before.

Though television was now willing to report more of the truth of America’s rebellion, it was unwilling to take a controversial viewpoint itself, as Murrow and Friendly would have done. Public television, through PBS’s predecessor, National Educational Television (NET), tried to, with an Inside Vietnam documentary that was promptly attacked by a number of members of Congress as being un-American and pro-Communist. Two young comedians who had quickly risen in the ratings with their Smothers Brothers TV show tried to reflect the mood of the country and angered their network, CBS, by insisting on putting on the folk guitarist and singer, Pete Seeger, playing his popular anti-Vietnam War song, “The Big Muddy.” The Smothers Brothers continued to inject political and social humor and comments into their programs until the following year, when CBS, still headed by William Paley, abruptly threw them off the air for not being, as the network put it, sufficiently “mainstream.” Was Joe McCarthy laughing in his grave?

The Tet Offensive in Vietnam in early 1968—a bloody, massive assault by Vietcong and North Vietnamese forces into South Vietnam—revealed an enemy stronger than the military had led the public to believe. Key opinion makers like Walter Cronkite began to express misgivings about the war. Given the turmoil and the mood of the country and the erosion of his popular support, President Johnson made a television address in which he described the state of the war, announced a halt to the U.S. bombing, and then, unexpectedly, stated he would not run for reelection.

The “Birth” of Public Television

Public television in the United States has never been as vibrant as most of its foreign counterparts, primarily because it was the “second child,” emerging long after commercial broadcasting had been entrenched as the primary system. Even when it moved from a loose confederation of local and generally poorly funded noncommercial, educational television stations into a more cohesive structure called National Educational Television (NET) in 1963, it was still teetering on the edge of irrelevance, relying on mostly stale prerecorded programming. Some feared it would follow the path of educational radio, which began with great enthusiasm, then through a combination of events fell into near total neglect. Public television’s fortunes began to turn in 1967, when, with the backing of the Ford Foundation, it was able to interconnect a number of educational stations with several hours per week of live programming featuring a weekly Sunday night news and feature program, the Public Broadcasting Laboratory. It was also in 1967 that the Carnegie Commission on Educational Television issued its seminal report that defined the mission for a public broadcasting system, and political leaders began to take serious notice, eventually leading to the passage of the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967.

Fig 6.14 Pacifica Radio has presented some of the medium’s most innovative and controversial programming since its inception in 1949.

Courtesy Pacifica Radio.

The nation’s attitudes spurred some changes in broadcasting. In Boston, a group of mothers concerned about the increasingly low quality of children’s programs, including violence, sexism, racism, and the cupidity of advertisers, formed Action for Children’s Television (ACT), which during the next few decades proved to be a thorn in the side of the FCC, Congress, broadcasters, and sponsors in its attempts to improve the quality of children’s programs and reduce the avarice of commercials. ACT continued into the 1990s under the leadership of one of its original founders, Peggy Charren.

One of the emerging gurus of underground broadcasting was Lorenzo Milam, who, frequently without compensation, helped radio stations get on the air and develop programming that reflected the attitudes and dissent of large, voiceless segments of the populace.