9. Constructive Design Research in Society

Any successful research program needs to be socially robust to live long enough to produce interesting results. Perhaps more than any other design research specialty, constructive design research has to work with many types of partners. This chapter looks at one project, Luotain (probe), conducted in Helsinki between 2002 and 2005 to illustrate how constructive researchers juggle between various demands in its environment. In the research world, Luotain juggled between information technology, industrial design, and art. It also needed to gain acceptance among design and business communities. It even contributed to public policy in Finland. Luotain managed to keep all of these interests in line for almost three years, which is a major achievement on its own.

Chapter 8 outlined the ways in which constructive design researchers use design things in their research process. Design things, we saw, gather people around actual design work. 1 Just as any research, however, constructive design research cannot stop there. Any research program worthy of its salt needs to function in society, not just during the project. Successful programs keep designers dialoging with society; unsuccessful ones are unable to keep this dialog going long enough.

1.While Ehn primarily follows Bruno Latour’s philosophy (especially Latour, 1987), this chapter takes most design readers to a more familiar terrain, pragmatism. In particular, Donald Schön (1983) did more than anyone in teaching researchers that design is a reflective dialog between designers and their materials. His perspective, building on pragmatism, was historically important in turning design research to post-Cartesian thinking, but it has its problems as well. In particular, it is too easy to misread Schön and exaggerate dialog at the expense of “design things.” Here, Ehn’s Latourian interpretation of design things comes in handy: it gives a far more important a place to those things that populate design practice. Precedents to this rehabilitation of material things are numerous; among writers we have referred to in this book, they most notably include phenomenologists and also Michael Lynch’s reinterpretation of ethnomethodology (Lynch, 1993). One of the founders of pragmatism, John Dewey, has been another constant reference in Ehn’s most recent interpretation of what makes design tools work (see Ehn, 2008, especially p. 99).

This chapter reviews constructive design research in society. As soon as researchers leave the university, they face rationalities different from their own. Many of these rationalities are beyond their control; more often than not, researchers find themselves in a subordinate position in activities initiated and controlled by people who think differently. 2 In practice, constructive design researchers work in a network of contracts and overlapping commitments. As various partners come and go into the projects with varying agendas, it is difficult to predict what comes out. Projects like these are “garbage-cans,” as Michael Cohen, James March, and Johan Olsen once famously called organizational decision-making processes. 3

2.See Abbott (1988).

To keep research going, researchers have to understand the demands society imposes on them. To function, researchers need to understand some of the rationalities they face outside of the studio. This chapter explores some of these rationalities through the example of Luotain, a key project in Helsinki’s empathic design program. Taking these demands into account improves the chances of success in research.

9.1. Luotain

Luotain (“probe” in English) was a design research project in Helsinki from 2002 to 2005. It was built around cultural probes that had been used in research in Helsinki since 1998. While the original British work on cultural probes sought to expand the mindset of human–computer interaction (HCI) researchers, Luotain took a step back and studied whether cultural probes work in company settings. 4 The practical goal was to improve product development in companies by introducing new, design-specific research methods. In practical terms, Luotain created concepts for companies. Product development, however, was left to the design firms.

4.For original formulation of cultural probes, see Gaver et al. (1999); for defense of building ambiguity into design research, see Gaver et al. (2004).

The project had thirteen participants. The coordinators were industrial designers at the University of Art and Design Helsinki. 5 Originally, participants consisted of five pairs of companies. Each pair had a company and its design partner and brought a case for the project, which was run as a series of cases with seminars and workshops in between. Later, this setup expanded to include an extra design consultant and new companies. Funding came partly from companies, but the main funding came from the National Technology Research Agency.

5.The leader of the project was professor Turkka Keinonen and the main researcher was Tuuli Mattelmäki, who received her doctoral degree in 2006.

The conceptual roots of Luotain were in an interpretive critique of emotions. By the end of the 1990s, the prevailing view in information technology was that emotions can and ought to be measured. Instead, Luotain turned to empathic, sociological, and interpretive theories of emotions. Emotions were seen as crucial to design and as social processes in need of empathic interpretation rather than directly measurable bodily processes (Figure 9.1). 6

6.One issue in the study of emotions is how much interpretation there is in emotion. Roughly, the dividing line goes between the positivists, who see emotions as biological processes, and constructionists, who stress interpretation (Kemper, 1981). For positivists, stimuli leads to certain states in the body, and people understand these states as emotions (Kemper, 1981). For constructivists, stimuli leads to changes in the body, but these changes need interpretation before they become emotions (Shott, 1979). Some mediate between these views, usually on Darwinistic grounds: in some situations automatic emotional responses are the last resort to survival, and emotions like fear are for that reason beyond interpretation, while other emotions have an interpretive component (Kemper, 1981). Few claim that more complex emotions like enjoying good design belong to the automatic category.The details of this debate are beyond this book. It is important to note, though, that emotions are also used to make sense of ourselves, and they often function as tactical and even commercial devices (Rosenberg, 1990; Hochschild, 2003). These social uses of emotions are the ones researchers in Helsinki were after, not (possibly) measurable emotions like a fear of snakes; hence, interpretive (or constructive) theories of emotions.

By any measure, Luotain was successful. It lasted about three years, and during this time it was able to attract company interest and funding. It also led to more than twenty scientific papers and Tuuli Mattelmäki’s widely admired doctoral thesis “Design Probes.”7 Its later impact can be seen in numerous studies. It has influenced dozens of master’s theses: some oriented to user research, some to concept development, and some to construction. For example, during Luotain Katja Soini was a doctoral student who went into organizational development and started to explore how design researchers can even participate in legislature. Another doctoral student, Kirsikka Vaajakallio, begun to explore how methods in Luotain were connected to participatory design; she first explored design games but later rediscovered the empathic roots of Luotain. Mattelmäki realized that through workshops many kinds of participants can be brought into design. Since then, this realization has led her to co-design. 8

7.Mattelmäki (2006).

8.This paragraph refers to several ongoing doctoral theses, built on Luotain, that are due to be published in 2011–2012. Workshops in the context of legislation have been explored by Katja Soini. Design games and their empathic roots are explored by Kirsikka Vaajakallio.

9.2. Researchers as Peers

Luotain found an audience in many research communities. The project plan in 2002 built mostly on literature in HCI, which was still fashionable after the dot.com bubble burst. The key papers in Mattelmäki’s Empathy Probes from 2006 were published in human-centered computer science conferences. This work was based on earlier work in smart products — small software-intensive gadgets that had become an important part of the design business in the 1990s. 9

9.In Helsinki, Keinonen (1998) and Säde (2001).

The audience soon started to change. Luotain started to build on the notion of user experience, a term that had been introduced to design more than ten years earlier and had become popular after the turn of the century. For Luotain, this term opened doors to HCI and design research. By the end of the project in 2005, researchers were publishing in HCI conferences and journals as well as in more design-oriented conferences like the Royal College of Art’s Include. Subsequent projects continue to be seen in all of these venues. 10

10.Design conferences include the International Association of Societies for Design Research (IASDR), Nordic Design Research Conference (Nordes), Designing Pleasurable Products and Interfaces (DPPI), Design and Emotion (D+E), and Design Research Society in England (DRS). Popular journals are Design Issues and Co-Design Journal, among others. Popular human–computer interaction conferences like Computer-Human Interaction, and a host of smaller conferences like Designing Information Systems, Computer-Supported Collaborative Work, Participatory Design, and Mobile HCI.

For researchers, this is basically a safe world. Researchers may disagree on many things, but they share many goals. In this world, they are able to gain a high degree of control over their activities and ways of thinking, and they know a great deal about its ways of reasoning.

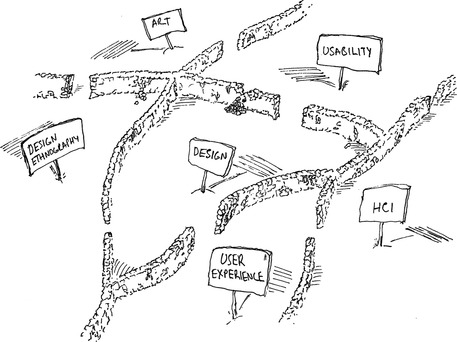

However, there are also differences. Interaction designers, for example, mostly build their research traditions on computer science and psychology. They favor theory building, experimental research, and statistical analysis. For empathic designers, this can be a hostile environment: there are few pockets of sympathetic reviewers. In ethnographic communities like the Ethnographic Praxis in Industry conference, empathic designers find people who understand interpretive research. Still, there are many dividing lines here too. For example, one issue is whether research should provide inspiration for design or whether it ought to be based on careful documentation, analysis, and theoretical work. 11 In artistically oriented communities, even interpretive research may be too analytical because it stresses writing at the expense of exhibitions (Figure 9.2). 12

11.See Chapter 5.

12.See the conference the Art of Research, the Design Research Society’s Experiential Knowledge Special Group, and also the new Craft Research journal.

Constructive design researchers place their work on this palette of communities in several ways. For example, researchers in Eindhoven mostly publish in HCI conferences and journals but also find outlets in design. Critical designers publish in both places but have focused on HCI for most of the decade. They have only recently come back to design much like the participatory designer places in Scandinavian design universities and empathic designers in Helsinki.

As design research has matured and gained a degree of academic autonomy, there has been a marked trend toward design as a disciplinary base. Still, constructive design researchers keep publishing in several communities. Interaction designers have increasingly been interested in the material, cultural, and social sensitivities every good designer works with and are willing to learn from their practices. The scientific leanings of HCI occasionally clash with the creative leanings of designers, but the gap is far less pronounced than it was a decade earlier. The HCI community has become far more receptive to design, setting up a design subcommittee at its CHI conference in 2009.

Constructive design research has also found a home in many design schools. Often, however, design research in these schools focuses on history, aesthetics, and critical studies. Also, traditional design disciplines like ceramics and textiles define their future through art, not research. Perhaps for these reasons, constructive design research usually takes place in industrial and interaction design programs. Constructive research widens the research basis of art and design schools but may also create a split between the humanities. However, as most constructive design researchers build on interpretive thinking, art, and design, there are also many things that create bridges to the humanities.

9.3. Research Faces Design Traditions

Luotain was created after about ten years of work on smart products in Helsinki, 13 but it put methodology into a new theoretical context. The main research question was inspiration rather than usability: finding new design opportunities rather than optimizing products and product concepts. The leading idea was that designers need to understand people before they can start designing. This idea came to be known as “empathic design,” even though “interpretive design” would have been a more accurate term. Innovative research methods, as Carnegie Mellon’s Bruce Hanington has called them, quickly became a meeting point for researchers, companies, designers, and other stakeholders. 14

13.Around 1995 to 1999, smart products were much like computers had been 15 years earlier. Before 1995, few people carried complex electronic devices like mobile phones in their pockets and bags. With portable stereos and mobile phones, designers faced usability questions that were much like those met in Silicon Valley in the 1980s. Designers could not assume that the users were professionals or could even be trained to use products. Products had to be built for people, not the other way around.In research in Helsinki, usability became a research focus. While some work focused on consumer preferences, other pieces of work focused on developing methods for studying usability. Methods like paper prototyping were borrowed from computer designers, used in collaborative projects with industry, and then reported to HCI research communities.

14.Hanington (2003).

In terms of design, these were not obvious steps. Language in design had few concepts with which to describe work that was interpretive, relied on post-Cartesian theory, and used methods that were often inspired by twentieth century avant-garde art.

Still, for many reasons, Luotain found support in industrial and interaction design. For some designers, Luotain was putting on paper what any good designer already knew. For others, it was a research community’s answer to their interpretive self-image and that good design has to start from understanding people. Also, because Luotain borrowed many methods from design practice and its workshop-based methods of analysis were familiar to every designer, it was easy to integrate it into teaching and practice. Luotain’s primary creator, Tuuli Mattelmäki, was named the industrial designer of the year in 2008.

A somewhat harder nut to crack was the workshop culture at the heart of design. Traditional design education is a hands-on education, and the dominant tradition of design education still uses the Bauhaus as its prototype. 15 The Bauhaus gave design education the idea of combining art, craft, and industry, as well as the idea of bringing the best from other fields of learning into design. However, empirical social science was not a part of its program. 16 In many programs modeled after the Bauhaus, user researchers have hit their heads against this heritage. They have usually been placed into separate research units, away from design. 17 Luotain’s solution was to focus on the early-stage interpretive foundations of design work, concept search, and concept design, rather than plywood and screws. For practitioners, this is perfectly acceptable. Conceptual work belongs to good design, and many designers live by conceptual design rather than construction (Figure 9.3).

15.Why the Bauhaus has become a reference to design education is beyond the subjects covered in this book. It was only a small part of a much larger reform of design education in German-speaking Europe at the time (Siebenbrodt and Schöbe, 2009, p. 8ff). Also, its influence was, as Otl Aicher noted, felt more in museums than in actual life (Aicher, 2009).We believe the main reason it has become so prominent in historical writing goes back to the extraordinary talent from Weimar, Dessau, Berlin, and later, Chicago. With alumni like Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, Marcel Breuer, Walter Gropius, and Mies van der Rohe, it obviously receives more attention than its competitors in early twentieth century Germany, Switzerland, and Austria.

16.The reasons are solid: empirical social science was in its infancy in the heyday of the Bauhaus and mostly built on history. Most of the tools of post-war social science were simply not available for people like Moholy-Nagy.

17.After all, it is easy to be romantic about handicrafts. However, it is also good to remember some of the problems in craft and workshops; they tend to be male-dominated, tradition-bound, and means-oriented. Also, history certainly tells a tale that questions any romantic call back to craft. It is industrialization that has lifted us from poverty and improved our life standards, not craft. Some of these critiques are discussed in Ehn (1988a).

In broader terms, constructive design research has gained many sympathetic listeners in design. Since the 1960s, many things have been pushing design away from its practical roots. 18 Industrial design has made design a more abstract discipline, process-based rather than material- or form-based. CAD technologies have made the skills of the hand less important and pushed descriptive geometry to the sidelines. Design management has focused designers on brands, markets, images, and organizational processes. Interaction design had valued an ability to talk about behavior and meanings in the abstract and to think in terms of flows and logic rather than traditional design forms and materials. The media image of design has been conceptual and is on the verge of becoming artistic. Most recently, services and sustainability have pushed designers still farther into abstraction.

18.This is the situation in architecture, too, as Pallasmaa (2009) noted.

In this context, most practitioners have welcomed constructive design research. For them, its stress on doing has an air of familiarity. When they see researchers in studios and workshops, they find it easy to communicate with them on equal ground. Most ideologists of constructive design research are programmatically pushing into the heart of research. Some are even arguing for using research as a template for wider restoration of universities that have become dangerously scientific at the expense of practice. 19

19.Overbeeke (2007), Keitsch et al. (2010). For 50 years, industrial design turned to research to gain legitimacy at the face of the Bauhaus tradition, creating opportunities for researchers. See Valtonen (2007, p. 118 ff).It needs to be noted that departures from the Bauhaus tradition have happened in places in which design is business- and technology-oriented rather than artistic. There are exceptions, however. For example, critical design and the Presence Project both came out from Computer-Related Design, which was set up in the 1990s as a response to digital technology that had transformed design thoroughly in the previous decade. Computer-Related Design, headed by the graphic designer Gillian Crampton-Smith, was a multidisciplinary program from the very beginning but with roots in industrial design. It became the site for research after a research grant from Interval Research Corporation in 1994. Later, this program evolved into Design Interactions under Tony Dunne. For a brief history of Computer-Related Design, see Crampton-Smith (1997).

9.4. New Bauhauses: Digital and Electronic

Constructive design researchers face another type of environment in design programs at technical universities. Technical universities traditionally build design on science and engineering, not on art and craft. When designers in these environments turn to ubiquitous and tangible computing models, they often turn to industrial design as a model. At one extreme, the dream is to create a version of digital and electronic Bauhaus by merging technology and art. 20

20.Ehn and Crampton-Smith (1998).

A recent example of this type of program is K3 at Malmö University in Sweden. This program combines art, cultural studies, and communication. 21 Its research side builds on media studies as well as on participatory design and computer science. Its founders’ goal was to turn it into a digital version of the Bauhaus. For the program’s founders, post-Cartesian philosophy and contemporary art provided useful arguments that justified building workshops to enable experimental work. 22 Here, they continued their earlier work from Sweden, where several researchers had defined electronics and software as design material. 23

21.K3 stands for konst, kultur, and kommunikation, or in English, art, culture, and communication. For the original version in Swedish, see mah.se/fakulteter-och-omraden/Kultur-och-samhalle/Institutioner-och-centrum/Konst-kultur-och-kommunikation-K3/Om-Konst-kultur-och-kommunikation-K3/Design-pa-K3/, retrieved May 26, 2010.In his original manifesto for a digital Bauhaus, Pelle Ehn (1998, p. 210) wrote:Nostalgic this may be, but this, indeed, is the Bauhaus applied to the digital domain.

What is needed is not the modern praise of new technology, but a critical and creative aesthetic-technical production orientation that unites modern information and communication technology with design, art, culture and society, and at the same time places the development of the new mediating technologies in their real everyday context of changes in lifestyle, work and leisure.

22.In design in particular, Brown (2009) and Verganti (2009).

23.See Redström (2005).

The reasons for bringing studios to technological research are well explained by Pieter Jan Stappers of Delft University of Technology:

Interactive Rear-View Mirror

IP08 was a nine-week design class given at the University of Art and Design Helsinki in spring 2008. In this class, master’s level industrial design students went through user-centered design processes. Students had to create a design concept, learn the basics of microcontroller, learn some programming in C, and refresh the basics of electric circuits.

In 2008, the theme of the class was co-experience (Battarbee, 2004) in the car and safety while driving. Interaction between the front and the back seat at that time was a major road safety issue, taking people’s focus away from what was happening on the road, causing potential hazards, and introducing risks into the driving experience. The class wanted to give students a firsthand bodily understanding of embedded technology, in our case how sensors and actuators work, and this was stressed throughout the class from the first user studies to the final testing of the prototypes. 24

24.See IP08 (2008). In 2008, the participants were Kaj Eckoldt, Thorsteinn Helgason, Riikka Hänninen, Jing Jiang, Ella Kaila, Timo Niskanen, and Benjamin Schultz. Funding for the project came from the Nordic Innovation Center’s Ludinno project led by Tomas Edman. Instructors were Ilpo Koskinen, Jussi Mikkonen (electronics), and Petra Ahde (design).

Kaj Eckoldt and Benjamin Schultz built an interactive rear-view mirror. Their work process is described in Figure 9.4.

|

| Figure 9.4 Constructive research in the classroom. (a) User studies in Lahti, Finland. (b) Concept creation. (c) Studio work. (d) An experience prototype of howscreens could be used to mediate communication between parents and children.Eckoldt and Schultz rejected this concept and worked with real mirrors. (e) Eckoldt and Schultz are trying out early concepts with a Lego Mindstorms model in the workshop. (f) From the workshop. (g) They test another concept with Lego Mindstorms. (h) Mock-up of a child sitting in a baby chair. 25 25.Photos from the user study and experience prototyping are by Eckoldt and Schultz; others are by Ilpo Koskinen. |

Classically, design studios are known for their visual culture. Designers surround themselves with inspiring materials, sketches and prototypes; other designers in the studio absorb these visual sparks as well, and such visual outlets are known to set off unplanned and informal communications, and present people with unexpected inputs, which can serve as part of solutions and lead to serendipitous innovation.

In 2001, four research groups from our department started ID-StudioLab, in which staff, PhD students and MSc students on research projects worked in a studio situation to promote contact between different expertises and different projects…. It promoted the informal contact and sharing of ideas and skills, an undercurrent that can be as important for the dissemination of research findings as the official publication channels. Moreover, it formed a playground in which design researchers could “live with their prototypes,” an important ingredient of “research through design”….

The “living prototypes” were part of the “texture” of StudioLab, influencing and being influenced by dozens of researchers, students and visitors who all brought and took away snippets and insights according to their specific background. This is why design studios are so important for growing knowledge. 26

26.Stappers (2007, pp. 88–89).

This setting keeps the distance between the source of inspiration and reasoning small. ID-StudioLab is also located close to Delft’s workshops, and there is a small electronics lab next to the StudioLab. Proximity encourages researchers to explore their ideas not just through discussion, but also physically. However, StudioLab’s researchers also have expertise in user studies and in field-based evaluation of their prototypes. It is not a laboratory in which researchers explore things sheltered from reality; its boundary is permeable. 27

27.IO StudioLab has been home to many of the best doctoral theses in the Netherlands, including Djajadiningrat (1998), Wensveen (2004), Keller (2005) and Sleeswijk Visser (2009).

9.5. Meet the Business

Luotain was a novel experience to many company participants, just as it was for many designers. For instance, in Datex-Ohmeda, which General Electric bought during Luotain, the project was owned first by the company’s usability group. Many suspicions were voiced because the project did not follow the group’s standard practices and put many of them in doubt. When the upper management saw the value of the project, however, it began to be accepted. On the other hand, when Luotain worked with Nokia, it was not seen as a novelty. Nokia had been involved in European research projects that had used cultural probes, and many researchers working in the project had trained many Nokia designers.

With the exception of Nokia, Luotain prompted rethinking of products, product road maps, and in some cases product development as a whole as early as 2002. At the end of the project in 2005, companies were on the map. Former usability testing groups had by then evolved into user-centered design groups.

When Mattelmäki was writing her doctoral thesis, she interviewed companies that had been involved in Luotain. She learned that the main benefits of her “empathy probes” were that they provided inspiration and information on users’ needs and contexts for company designers, they allowed users to express their idea to product developers, and they created a dialog between users and designers. 28

28.Mattelmäki (2006, pp. 197–205).

There are other studies that show how constructive design research is attractive to industry and has been appropriated in businesses. When working with constructive design researchers, companies find research that helps them to identify opportunities. In addition, they provide concepts, prototypes, and well-crafted arguments that explain these. Constructive design research also prepares people who can go back and forth between theoretical ideas, studio work, and workshops, and who have the ability to plan and to work with materials and technologies. These are valuable skills.

There are some patterns in how research finds a place in business. With the exception of the smallest one-man firms, with few resources to buy research, several design firms have embraced design research, turning it into a strategic tool. On the one hand, research has helped design firms to diversify their offerings and to make long-term contracts with clients and land lucrative research contracts. 29 On the other hand, research adds value to the customer who does not want to buy research and prototypes from two different places. This business concept has been around since the early days of E-Lab and Cheskin and continues to thrive today. 30

29.This is especially true if they are able to link this new expertise to management consulting, as RED associates in Copenhagen. IDEO and previously E-Lab have provided important models for other companies.At the small-business and craft-oriented end of the spectrum, researchers face some of the same tensions as artists. As Howard S. Becker (1982) noted in Art Worlds, craftspeople routinely complain about “bad craft” in seeing artists’ craft objects. The complaint has institutional foundations. Art occupies a much higher position in society than art. When artists attempt pottery, for example, they are able to connect to media and wealthy clients in ways beyond reach by craftsmen, whose work, naturally, is technically much better. The strain is inevitable. No doubt, this is also the case with research. After all, research prototypes are barely ever meant to achieve a high level of craft, while research budgets can typically be only dreamt of by craftspeople.

30.For E-Lab, see Wasson (2000) and Wasson (2002).

On the client side, there are also patterns. At one end are small companies with few resources to invest in design. At the other end of the business hierarchy are global companies like Intel, Philips, Microsoft, and Nokia that have resources for extensive research. Widely known research programs from these companies include Intel’s former People and Practices Research group, Alessi’s research programs, and Philips Design’s vision projects. 31 Again, there are powerful economic reasons to invest in constructive design research. Failing in research is cheap compared to failing with a product (Figure 9.5).

31.For Intel, see Intel’s Reassessing ICTs and Development: The Social Forces of Consumption (Intel, 2010a), which presented a series of case studies of ICT use through a multi-site ethnography and contextualized these studies to social science literature on development. For Alessi, Verganti (2009) and Alessi and Zilocchi (2010); for Philips, for example, Aarts and Marzano (2003) and Vision of the Future (Philips Design 2005).

The first markets for constructive design research were born in cities with sophisticated design markets, such as Silicon Valley, the Scandinavian capitals, Munich, Amsterdam, and London. These places have had markets for highly specialized design services for decades, and they continue to create demand for new openings. A city like London can support companies that specialize in using documentary film in user research. 32

32.Like in Stbd, a design company based in Amsterdam and London that specializes in using documentary film for design. Its use of documentary partly builds on the doctoral thesis of one of its partners, Bas Raijmakers (2007). Companies like DesignIT in Copenhagen and Aarhus, Denmark, typically sell both research and design services. See designit.com/.

The Internet is currently creating a new interface between constructive design research and business. The cost of a start-up on the Web may be little more than having time for research, a laptop, and an Internet connection. Testing concepts is also cheaper than testing physical products. Publishing on the Web is easy, and Web-based marketing is cheaper than traditional marketing. The differences in producing hardware are significant: a solid concept for a new umbrella has to be sold to business angels, risk investors, banks, manufacturers, wholesalers, and department stores. We believe that constructive work may provide IT start-ups with useful ideas and a relatively cheap way to test their ideas and strategies. In the world of bits, research gets a far more important role as the driver of innovation than in the world of atoms.

9.6. Embracing the Public Good

Design takes place in the market, but this is only one side of the story. The other side is the public sector. When funding comes from public sources, research is expected to produce something the market fails to do. Examples include plans and concepts for public spaces, new infrastructures, and for “special” groups too small to attract product development money from the private sector.

Again, Luotain is a good example. Although the public sector was not involved in the project, it made the project possible in several ways. It was mostly funded by public sources, and for this reason, it had to have several participants, and it needed to publish its findings to benefit society, not just participating companies. Besides, political considerations made the project possible in the first place. Funding for the project came from a government program, Muoto 2005!, which aimed at rebuilding Finnish industry through design. Policy work that led to the Muoto 2005! program had been done in part by professors at Luotain’s home department.

Local and national governments have funded many key constructive design research projects in Europe, and the European Union is another major source of funds. 33 Some of these projects have become important milestones on the road toward constructive research, like the Presence Project and Maypole. 34 Both were funded mostly by a consortium where part of the money came from industry seeking applications, but long-term continuity was built on funds from public sources.

33.Many examples we have shown in this book, such as DAIM (Halse et al., 2010), Luotain (see Mattelmäki, 2006), and Switch!, received funding from national sources in their home countries. On the other hand, the EU funded the Presence Project and Maypole.

34.Presence Project (2000), Mäkelä et al. (2000).

Many European and Asian countries, such as the United Kingdom and the Scandinavian countries, and South Korea, New Zealand, South Africa, and India have similar design policies. The European Union was also preparing its design policy from 2008, building it mostly on experience and thinking from Denmark, Finland, and the United Kingdom. Small European countries, in particular, have integrated design and design research into their industrial and innovation policies.

Constructive Design Research in Innovation Policy

Constructive design research is a winner in many political discussions about what kind of research should be funded. 35 Its value proposal is flexible and robust. For companies with enough intellectual, technological, and fiscal resources, it leads to prototypes that companies may use in various ways, which is another promise field research can make. Like any research, it promises knowledge that is in the public interest. Profits from relatively small investments in research can be significant.

35.Other winners are obvious: research in technology and business.

In particular, fieldwork is directly relevant for industrial interests. This is hardly surprising, given the roots of field research in industry and global companies’ investment in it. The key word has been user-centered design. However, field research fits best under this concept. The word “design,” for its part, creates the connection to industrial policy, which currently usually comes under the label of “innovation policy.” Conveniently enough, “design” also has an air of creativity. This sounds like a marriage made in heaven.

The link between user-centered design and innovations has become the cornerstone in policies in Denmark, India, and more recently, the European Union. For example, the European Union has titled its design policy document as “Design as a Driver of User-Centered Innovation.”36 In this document, design is distanced from aesthetics and styling, and firmly situated in the realm of user-centered design. In these policies, design typically complements more traditional innovation activities such as research. Design and other non-technological innovation drivers like organizational development are less capital intensive and have shorter pay-back periods than, for example, technological research but still have the potential to drive competitiveness.

36.European Union (2009, p. 2).

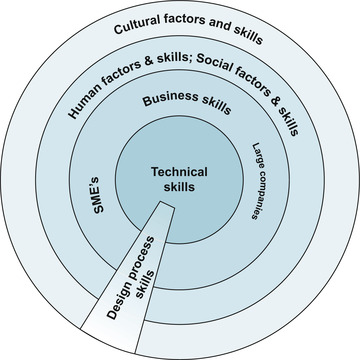

For example, the Muoto 2005! program in Finland aimed to increase the number of design graduates and to better connect design with industry. 37 It was surprisingly successful in both respects, but more relevant to our concerns is its conceptual structure. It consisted of concentric circles, with technology in the middle, business around this core, and social and cultural “factors” at the outer circles: design connected these circles. This delightfully simplistic model became the structure for both technological and social science and humanistic research. With the exception of a few theoretical studies, and some technology studies in industry, most research funded in this initiative was user-centered (Figure 9.6).

37.For Muoto 2005!, see Saarela (1999).

Designers have been more than passive partners in preparing these policies. A good deal of expertise for policy preparation came from the top of the design world, which had a plenty of resources needed to participate in the time-consuming and often tricky world of policy making.

In Muoto 2005!, most of the background preparation work was done in the country’s largest design school and its design department. When the policy was running, management was delegated to business consultants. The university had expertise, money, and enough resources to participate in this work, which does not lead to billable hours. It was also sufficiently removed from industrial interests to be capable of articulating the larger interests of the design community.

The main exception is the United States. Although it has gone through several attempts to construct a design policy, little has been produced, and most funding is based on private funds. 38 America channels public funds to design, but usually through funding national security, which is impossible to track. 39 Other major stable sources of funding outside of the market are major foundations, but as far as we know, no systematic studies of how design has fared in their boards exist. 40 There is no way around the public good argument in America, although it does not work in the same way as in Europe.

38.For the latest effort, see designpolicy.org/from 2009. This effort came from the design world. In Europe, the main drivers have been people with power, usually either administration and politicians, or major corporations.

39.Historically, the military was an important source of revenue for design firms run by Henry Dreyfuss, Walter Teague, and even Raymond Loewy. Although the details still remain under the veil of secrecy, ergonomics is in debt to military spending that started during World War II. See Flinchum (1997, pp. 78–87).

40.To see how Herbert Simon connected with the Ford, Carnegie, and Rockefeller foundations to pool resources for psychology, management, and computer science at Carnegie Tech (now Carnegie Mellon University), see Crowther-Heyck (2005, pp. 149ff). Crowther-Heyck does not mention how design was progressing on Simon’s agenda for the university. A more recent example is the now defunct Interval Research from Paul Allen, which funded what came to be one of the key projects in shaping constructive work, Presence.

Public funding introduces designers to partners they would not ordinarily work with. These include a host of engineering specialties but also several sciences, research institutions, service companies, public sector organizations, and non-governmental organizations. In this world, design researchers have learned to explicate their aims and methods with new types of arguments. The best recent example is probably Material Beliefs, a London-based project exploring potential implications of biomedical and cybernetic technologies. The project cooperated with engineers, scientists, and social scientists but aimed at producing prototypes, exhibitions, and debates rather than just scientific papers. It was funded by Britain’s Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, which had a program about public involvement in science. 41

41.See Beaver et al. (2009).

9.7. Constructive Design Research in Society

This chapter reviewed constructive design research in society by illustrating it with Luotain, a study done in Helsinki from 2002 to 2005, with many spillovers that still continue. Luotain first oriented to HCI but later turned to design. Its home base was industrial design, but compared to design-as-usual, its aims were considerably abstract. Still, its methods were largely borrowed from design. Its business context was lively: eleven companies participated in the project. Luotain avoided product orientation but was business friendly. Finally, it had a public dimension through funding from the National Technology Research Agency. It was to produce knowledge for the public domain, which it did.

As Luotain illustrated, constructive design researchers face many types of rationalities. Some of these rationalities are close to home, such as in the research, design, and business worlds. Some others are distant such as the idea that public good seldom figures in designers’ minds. It can be difficult to keep all of these rationalities in line, but Luotain managed to do that with design things and workshops. The project elaborated on the empathic design program a great deal, first by taking it into a more workshop-based methodology and, later, through co-design and service design. Projects that build on Luotain today seek inspiration from scenography and environmental art. 42

42.For workshops, see Soini and Pirinen (2005); for more artistic work, see Mattelmäki et al. (2010) and the Spice Project at designresearch.fi/spice.

How researchers face these rationalities depends on their positions in research and the social organizations that surround it. Researchers in Luotain concentrated on project work, published in conferences, and worked with businesses and occasionally in seminars organized by the National Technology Research Agency, where they saw a glimpse of technology policy. However, abstract arguments about public good were far from their minds; instead, they worried about design and conceptual frameworks, and tending to the public good was reserved for senior professors and university presidents. Indeed, many who inhabited these lofty heights were not from the design side; they were managers, industrialists, politicians, university presidents, and senior public servants.

Other programs relate to society in different ways. For example, research in Eindhoven has technical roots and builds on HCI, which is an accepted part of research in engineering and shares its mathematical beliefs. This is in stark contrast to research in art and design universities like the Royal College of Art, in which constructive design researchers share vocabulary, techniques, conventions, and methods for breaking social conventions with contemporary artists. Scandinavian research, on the other hand, falls in between. To make a constructive design research program socially robust, it has to respond to the demands of its local environment. 43

43.“Socially robust” is from Nowotny et al. (2008).

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.