Chapter 4

Research Planning

Never research in a vacuum. Every piece of user research is part of the ongoing project of understanding your users, whether they are longtime customers or mysterious strangers who have never heard of your product. Making a research plan supports that project in several ways: It spells out the goals, sets up a schedule that helps you deliver results when they’re needed most, and lets you avoid unnecessary, redundant, or hurried research. It can help you communicate about the research and make it easier for colleagues to participate and to act on the results. It also helps defeat the most frequent objection to doing user research: “We just don’t have the time or budget.” But even if you don’t show your plan to anyone, it will help you figure out what to research when. You should start working on a research plan as soon as you’ve decided to do any research at all, even if it’s only a tiny usability test or some client visits.

A research plan consists of three major parts: why you’re doing the research (the goals), what you’re doing and when you’re doing it (the schedule), and how much it’s going to cost (the budget). These are in turn broken up into practical chunks such as report formats and timetables. To get the most out of research the soonest, you should integrate the research plan with the product development plan. Sometimes, however, this is the most difficult part.

Make a Research Plan—Now!

The rest of this chapter will explain a thorough process for establishing your questions and identifying ways to solve them. But essentially, all your plan has to do is cover five areas:

1. The questions that you are trying to answer

2. Why it’s important to answer them

3. The techniques that you will use to answer each question

4. The resources (time, money, people, equipment) you will need. (If you do not have any of these resources guaranteed, you may also need to include an argument about why you should be granted them, or where you will find them.)

5. When and where the research activity will take place, and who will do it

And that’s all. In the last part of this chapter, we’ll give you a very detailed example plan that you are free to adapt as you see fit. But you can scrawl your research plan on the back of a napkin, if that works for you and the clients for your research.

Setting Goals for Research

Before writing a research plan, you need to know two things: why you’re doing the research and how your results will be acted upon. Together, you use these two things to figure out which questions to ask, in what order, to have the most impact on the product.

The first involves determining business priorities and setting research goals that can meet them. The second involves an understanding of the development process so that the research can make the greatest impact on the final product.

There are many reasons why you could be initiating research. Maybe your company has a product that could be performing better, maybe it’s developing something new and you want to see if the concept is appealing before investing the resources to code or build it, or maybe you are trying to figure out what product or service you should create. Wherever you are at the outset, you should begin your research with the people it needs to inform and with their definitions of success.

Every department in your company has a different method of measuring its success. Development could measure success as meeting the schedule or the number of bugs per thousand lines of code. Marketing could look for the number of positive reviews and increased site traffic. Identity design might care about the ease with which the product is integrated into the corporate brand. Customer support might want to decrease the number of questions they have to field. Sales wants to bring in more revenue. Each of these represents a different perspective on the final product, and each demands something different from the user experience.

Research can go on in any direction. To get the most benefit, it needs to target the most important features of the product. But a product’s “features” include much more than just its form factor or screen layout. Its most important features are those that affect the business goals of the company. Thus, the first step is to make a list of issues or ways in which the product’s user experience impacts the company. Each issue represents a goal for the research program; it focuses the research plan and helps uncover how the product can be improved for the greatest benefit to the company. Collected and organized from the perspective of the company, these issues will not (and should not) focus solely on the user’s ability to efficiently use the product. There may be goals for advertising effectiveness, customer support load, brand recognition, and so forth.

In other words, since the user experience affects every facet of the product, you should consider every facet. The process consists of three steps.

Collect Issues and Present Them as Goals

The process of determining the important issues can be a research project in itself. Sometimes one person requesting the research will claim to know all the issues it should address, but wherever possible you should take your own inventory.

Begin by identifying the stakeholders. Every department will own some piece of every product, but some will own more than others (or will care more). The product manager—who is probably the most important person to talk to, anyway—can help start the list since he or she will know which groups and individuals have the biggest stake in the project. These will almost certainly consist of engineering, design, marketing, and sales, but it can include any other department that has a stake, or say, in the product’s success. There could also be a significant managerial presence in a product if it’s a major moneymaker (or loser) or if it’s brand new.

Sample Sport-I.com Stakeholder List

Alison, VP of Product Development

Erik, Interaction Design

Michel, Marketing

Sun, Front-End Development

Janet, Sales

Ed, Customer Support

Leif, QA

Joan, Identity Design

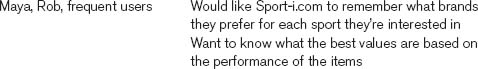

Maya, Rob, frequent users

If there is no single person who’s responsible for the product in a given department, find the person who dealt with it most recently. Odds are that this person regularly deals with it or can tell you who does. Once you have your list of stakeholders, find out what they consider to be the most important issues. You can do this either by getting all the stakeholders together to spend an afternoon setting companywide priorities for the product, or by speaking to each person independently (often a necessity with executives and other busy people). The latter is often a good idea if there are strong disagreements and you want to make sure that everyone’s viewpoint is heard.

The key questions each person (or department) should answer are as follows:

• In terms of what you do on a day-to-day basis, what are the goals of the product?

• Are there ways that it’s not meeting those goals? If so, what are they?

• Are there questions you want to have answered about it? If so, what are they?

Once you’ve talked to all the departmental representatives, make a list of the goals and issues.

User Experience Goals and Questions for Sport-I.com

What if stakeholders have conflicting goals? An advertising sales manager may want to increase revenue by introducing additional ad units at the same time that the vice president of content wants to add more news stories to the home page. Since there’s a limited amount of real estate on the interface, these goals may appear to be at odds with each other. At this stage, it’s too early to attempt to resolve them, but investigating the relationship between them may be an important near-term goal for the project.

After you’ve talked to everyone in-house, you should talk to a couple of users for their perspective. That may seem like a catch-22: Why research the user’s needs before you even have a plan to research their needs? Because getting their voice into the research plan gets the research focused on them early and sets a precedent that can prove important in selling your research efforts within the company. See Chapter 6 for some hints on how to find users to talk to. Add this information to the list.

As part of this process, you should try to collect the other user experience knowledge that may be floating around the company, answering research questions without doing any original research. This can include surveys done by marketing, customer support feedback summaries, interviews by the development group, and unused reports from usability consultants. The user experience researcher can play the role of information collector and integrator, and, becoming the repository of all user-related information, spread information about the value of user experience research, and build stakeholder trust in the process. More information sources are described in Chapter 14.

Prioritize the Goals

Based on your interviews, you will have some idea of the corporate priorities with respect to the goals you’ve defined. Some things may be important because they’re seen as preventing people from using a key feature of the product. Others may be important because they differentiate the product from its competitors, or because work to address them is being planned for the near future. Still others might be less important because they may create a big drain on resources or are currently a hot topic of debate within the company.

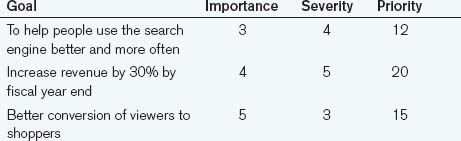

To get an idea of the order in which to tackle the research, you should prioritize the questions. If the prioritization is unclear, you can try the following exercise (which uses the same technique as in Chapter 11, where it applies to choosing specific features).

A Prioritization Exercise

Make a column next to your list of questions and label it “Importance.” Go down the list and rate each item on a scale of 1 to 5, where 5 means the feature affected is a “must have,” critical to the success of the product, and 1 means it’s a “nice to have,” but not essential.

Next, make a second column and label it “Severity.” This will reflect how bad the problem is. Write a number on a 1 to 5 scale here, too. Five represents bad problems (generally ones that are directly affecting the bottom line right now), and 1 refers to problems that are annoyances or information that would be good to know.

Now multiply the two entries in the two columns, and write the result next to them in a third column called “Priority.” This combines and amplifies the two factors in deciding which problems should be investigated when. Ordering the list by the third column gives you a starting order in which to investigate the product’s user experience.

You should now have a prioritized list of what the company as a whole considers to be important user experience questions. There shouldn’t be more than half a dozen or so “big” questions and a dozen or so smaller, more specific ones. These, taken together and coupled with a schedule, a budget, and some more fleshed-out goals, will be the heart of your research plan.

Rewrite Goals as Questions

With the product goals in hand, start rewriting the goals raised during your interviews as user-specific questions or information to be gathered. Broaden narrow questions into general topics to get at the root causes of the problems. If there’s a concern voiced about a specific feature, for example, you may need to broaden the focus to include the underlying reasons for that feature’s existence.

The questions should be simple so that they give the most bang for the buck. Every problem presents a host of questions and issues, many of which are complicated and interrelated. But this is “easy pickin’s time.” Pick one or two questions for each goal that, when answered, will address the goal. When you later research and revise the plan, you’ll be able to tease out the more subtle questions and important interactions.

Goals for Sport-i.com Rewritten as Research Questions

Expand General Questions with Specific Ones

In the final step, flesh the larger, more abstract questions into specific ones that can be answered by research.

Of course, not all these questions can be answered in a single research project or by a single technique, but having a big list of questions from which to draw can help you when you’re putting together your research schedule. Moreover, the process of making the list often helps define the boundaries for the larger issues, reveals relationships between the larger issues, and sometimes reveals new questions and assumptions.

Tips

Never go into user research to prove a point, and never create goals that seek to justify a position or reinforce a perspective. The process should aim to uncover what people really want and how they really are, not whether an opinion (whether yours or a stakeholder’s) is correct

Learn the product thoroughly. Research goals can be framed more precisely if you can understand how the software currently works. Do what you can to become a user: Read the documentation, take a training course, and talk with tech support.

Be prepared to deal with fundamental questions about the product. If a question comes up during research—even if it’s “should we be in this business at all?”—then there should be a way to deal with it and create research that will answer it (or at least escalate it to a senior stakeholder who can address it).

The mantra for determining which questions to ask is simple.

Test what’s testable.

Don’t ask questions whose answers won’t be actionable or test things that you can’t change. For example, it’s generally of little use to inquire about the identity design of a product before the feature set has been determined since the feature set will greatly shape the product’s identity. Likewise, it’s fairly useless to be researching feature desirability after you’ve already committed to an interaction design since the design assumes that people want what it’s showing them.

Integrating Research and Action

Now you know what your objectives are in doing research, and what you aim to find out. The other critical input you need is how your research will be used. Are your findings expected to inform product development? Product marketing? Customer support or policy? Are the questions you answer going to shape the next release of the product? The next few years of releases?

Just as every part of the business has their own goals that lead to different questions, they all may operate on different schedules, with which research may need to coordinate. You can never predict exactly how and to whom your research will be useful—if you could, it wouldn’t be research. On the other hand, it pays to deliver research findings when stakeholders need them most. For example, if you want to know how your prototype fared in usability tests before developers start to implement the new design, you need to build that timing into your research plan.

To gather these schedule requirements, start by talking to the person immediately in charge of the product. Go through your list of questions. For each question, find out if there are key milestones or deadlines for acting upon the answers. You may need to follow up with other team members to get the detail you need. Once you know the critical dates on the product’s road map, you can work backward from those dates to determine how much time you have to do the relevant research. Based on this information, your priorities, and your available budget, you can then select the research techniques you will use and the sequence of research projects.

Don’t assume that if time is short, you should forego research until after the product is released. If you can argue that the findings from research will increase the product’s chances of success, you may be able to change the schedule to allow for it. See Chapter 19 for more ways of integrating user experience research into your corporate culture.

Agile Software Development and User Research

In 2001, 17 developers published the Agile Manifesto, advocating a new way to build software. In their words, this approach values “individuals and interactions over processes and tools; working software over comprehensive documentation; customer collaboration over contract negotiation; responding to change over following a plan.” (The complete statement is posted at agilemanifesto.org.) Agile and similar “lightweight” methodologies have steadily gained popularity among engineers and have been adopted by large and small software companies. When user research is involved in their efforts, researchers must also “work Agile,” planning research projects to inform short, frequent release cycles. This typically affects the research plan in several ways:

• Research that gathers general product requirements is completed before any development starts.

• Prototype and product testing is done in many short rounds; each round is focused on a small set of features to be built in the next development cycle.

• Research reports are brief and are often delivered to the team orally rather than in documents.

• Since customer requirements can change on short notice, research plans have to be updated frequently.

A further evolution of this thinking is the Lean Startup movement, first described by software entrepreneur Eric Ries on his blog startuplessonslearned.com. Addressing the specific case of new product development, Ries argued in 2009 that innovating at low cost requires a “continuous cycle of customer interaction” featuring “rapid hypothesis testing about market, pricing and customers,” along with continuous software releases. This philosophy has broad implications for research planning in a startup environment. Agile release cycles drive usability cycles in which recruiting, testing, and analysis take less than two weeks, rather than the three or more weeks that have been more typical of the industry.

The output of every research technique not only provides information on how to improve the product, but also can focus subsequent research. Surveys describe the current audience so that you know whom to recruit for interviews. Field visits and interviews outline their problems, which can motivate the development of features. In turn, usability tests evaluate the features. Every piece of information that research provides helps you know who your users are or what they want.

Thus your schedule of research projects, although constrained by immediate priorities and the development schedule, should still be organized so that one project informs and reinforces subsequent projects. In practice, this means that procedures that gather general information fall before those that collect information about specific preferences and behaviors.

Starting Research in the Beginning

For a new product or an existing product in an early phase of redesign, the following order of research projects makes sense. Realistically, you will probably only have time for a few of these projects given the usual schedules of product releases and new product development. This is where it helps to have prioritized your research questions; the techniques you choose will depend on what types of questions are most critical.

Early Design and Requirement Gathering

• Internal discovery to identify the business requirements and constraints.

• A survey to determine demographic segmentation and technology use of the existing or proposed user base. (Surveys are described in Chapter 12.)

• Usage data analysis of their current behavior if such data exist. (Usage data analysis is described in Chapter 16.)

• Usability testing of the existing product to uncover interaction problems. And competitive usability tests to determine strong and weak points in the competitors’ products. (Usability testing is described in Chapter 11.)

• Observational field visits (Chapter 9) and diary studies (Chapter 10) to uncover current experiences (both with the product and with the task it’s supposed to aid), and to specify how they solve them right now.

• Two to three rounds of focus groups (Chapter 7) or interviews (Chapter 6) to determine whether people feel the proposed solutions will actually help them and which features are of highest value. And competitive focus groups to determine what users of the competition’s products find most valuable and where those products fail them.

After Release

• Surveys and usage data analysis to compare changes in the product to past behavior.

• Diaries (Chapter 10) to track long-term behavior changes.

• Observational field visits (Chapter 9) to study how people are actually using it.

Starting in the Middle

A user research plan often may have to begin in the middle of a development cycle. Decisions have already been made about who the users are, what their problems are, and what solutions to use. These cannot be revised—at least until the next development cycle. In such cases, the research plan should begin with procedures that will give immediate benefit to the product before release and plan for more fundamental research to take place during the next development cycle. The following order may make sense for such a project:

Design and Development

• Rapid iterated usability testing and competitive usability testing until release. (Competitive research techniques are described in Chapter 5.)

Organize Research Questions into Projects

Let’s go back to the example. In the list of research questions, it appears that there are some quantitative questions about people’s current behavior (the ratio of abandonees to those who complete a transaction, the page where the abandonment happens, etc.), and there are questions about their motivation and understanding of the site. The first set of questions can be answered through log analysis, and the second set can largely be accomplished through usability testing. There’s one question, “How do they shop on the site?” that’s probably too abstract to be easily answered through usability testing. It’s one of those fundamental questions that will probably need to be researched over an extended period of time and with several different techniques. It can begin with a round of observational research.

![]() Visit this book’s website at www.mkp.com/observing-the-user-experience for more research planning resources.

Visit this book’s website at www.mkp.com/observing-the-user-experience for more research planning resources.

Choosing among the Techniques

Picking the right techniques and grouping them can be difficult. The more experience you have with the methods, the better you will know which techniques best address which questions. If you don’t have any experience with any of these techniques, start with the descriptions in this book, and pick one that seems right. Try it out. If it doesn’t help you answer your question, note what kinds of information it was able to gather well and try a different technique.

Here is a table of the techniques with some trade-offs. It provides a basic overview of the techniques, but it’s certainly not comprehensive.

Based on what you know about the company priorities, group the questions into clusters by technique, and make a rough schedule. Usage data analysis starts immediately, whereas the usability testing will take several weeks to prepare and recruit. The site visits can start at just about any time. However, in this hypothetical situation, there are not enough resources to do a complete study. So, a small round begins immediately with the assumption that more will take place later.

Continue through your issue list in order of priority, expanding all the items this way. As you’re expanding them, look for similarities in the questions and places that research can be combined to simultaneously address a number of issues. In addition, look for places where competitive analysis can produce an interesting perspective. You can also start with the list of techniques and use that to generate further questions and research ideas. So, for example, you could start by saying, “What can we learn with observational research? Will that address any of the research goals?” and work your way through the other techniques.

A single entry from the final list could look something like this.

Consider this entry as a single unit for the purposes of scheduling. It’s a block that can be put into a scheduling or project management program. The specifics of what is tested may change later, but a list of techniques and questions will allow you to put together a good idea of what is to be tested, and when.

Asking Questions across Multiple Projects

Most product development schedules are fast paced, so the plan should concentrate on the short term. However, it should not short-change the long term. It’s always tempting to focus on the goals for the next release and leave fundamental questions about a product and its users to long-term projects. But deeper answers are precisely what can make or break a product over the long run. Don’t put off answering these questions because they seem too general or difficult to answer. In fact, they should be investigated as soon as possible. The earlier they produce results, the sooner that planning, design, and implementation of core product changes can be made.

However, only focusing on deep questions when there’s an upcoming release is rarely a wise plan, from the perspective of either the product or the researcher’s success within a company. Thus, the research plan should be structured as a set of parallel projects, with long-term goals cutting across several projects. Each project addresses whatever short-term questions need to be answered but also asks a couple of key questions to nudge knowledge about the fundamental questions forward, too.

This can be represented as a grid. Each fundamental question is in a column, while research projects label the rows. Thus it’s possible to keep track of which projects are asking questions about which fundamental goals they’re addressing. This keeps long-term goals from being neglected by the research process. The following table shows one such representation, with the colored cells representing which project gathers information investigating which goal (with project 4 an in-depth investigation of issues studied in projects 2 and 3).

Tracking Goal Information Collection across Research Projects

Of course, not all projects are going to provide data for every goal, but keeping this structure in mind will allow you to keep the long-term needs in perspective while still getting the short-term work done.

The research plan should be updated frequently: in between every round of research, with every major change to the product and, in general, with every addition to the knowledge of the user experience and whenever company priorities change. It would not be unusual for there to be updates every week or two. Versioning every update helps keep track of all the changes.

The Format of the Plan

Until this point, we have intentionally avoided presenting a specific structure or style for the research plan since those will vary based on your needs and resources. A plan should be flexible and adapted to your environment. If you use project management or scheduling software, a lot of the plan can be represented in it. If you plan to show it to management on a regular basis, it can be in a more formal written form that can be folded into the product development plan. If your company culture prefers to communicate using a wiki, it can be a set of wiki pages. Whatever. It should fit a style that is useful and comfortable for you, but that can be shared and integrated with the larger product plan. The plan is a document that you are going to use to communicate the structure of your research and to sell the value of your work to your product team and your company as a whole.

There are some things every research plan should do.

• Set expectations. The people conducting the research and the recipients of the results should know what research is being done, how it’s being done, and what results they can expect. Don’t overload expectations for any single round of testing. A round of testing will not validate or condemn the entire project, and it should not be expected to. A research plan should also communicate that it is a flexible and ever-changing document. This can be done through version numbers or even expiration dates (“This research plan is valid until 2/2/2013”).

• Set schedules and responsibilities. Who is going to do what when? How the research schedule integrates into the larger development process. This should be specific in the short term, but it can be more general in the long term, except for research that’s directly tied to the larger schedule.

• Specify goals. Every research project and the research plan as a whole should have specific goals associated with them. The goals collected at the beginning of the process drive the specifics of the research. It should be clear what they are.

• Specify outputs. There should be outputs for every research project based on the needs of the stakeholders, specifying the information that’s going to be presented. Ideally, the actual deliverables (report, presentation, workshop, set of personas, etc.) should be described.

Budgets

The budget will be based on the cost of resources available to you, but it’ll probably come in four big chunks.

1. People’s time (including your time and the research team’s time)

In our experience, useful times for calculating the duration of a qualitative user research project such as a usability test (including project management time and typical inefficiencies) are roughly as follows:

Quantitative research, such as surveys and log analysis, will vary greatly in effort based on the complexity of the task and the tools and expertise available. What a good statistician can do in a couple of hours can take days for someone with less training.

Incentive costs are described in detail in Chapter 6, but (as of spring 2012 in San Francisco) they tend to fall around $150 per person per 90-minute session for most research.

Likewise, equipment costs will vary based on how ambitious your research is in terms of documentation, how demanding it is in terms of space, and where you’re located. As of the time of writing, the cost of software for analyzing and recording usability tests ranges from free to around $1500. Renting a full lab, complete with software, can cost anywhere from $1200 to $1800 per day. And installing a permanent, high-end lab into your own offices will cost you about $30,000. However, you can also do an absolutely professional (albeit less highly documented) job for free: just take over an empty conference room and borrow a video camera.

Example: Research Plan for Company X

This is an excerpt of a research plan prepared with Indi Young, a user experience research consultant, for presentation to the development team of a consumer product comparison website. It presents an extensive research program designed to get a broad understanding of problems and users prior to a major redesign. Since it’s designed for presentation, it includes more process explanation than an internal document and fewer details than would be used for internal delivery (which would include tables like all the ones described earlier), but it gives a good outline of how such a research plan can look when fully expanded. (For the sake of this example, this plan is confined to the research, but in reality, it would probably reference production milestones.)

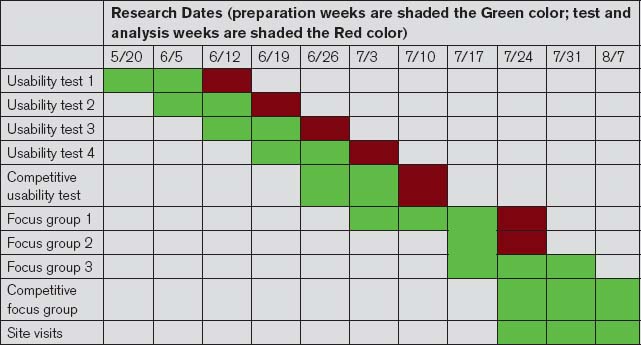

Summary

This research plan outlines the needs and goals of company X in order to conduct rapid user research on company X’s and the competitors’ products, and presents a schedule designed to meet this goal. It includes plans for five rounds of usability testing, four focus groups, and the beginning of an ongoing site visit process. A schedule of all research through the week of July 8 is included, and an estimated budget is proposed.

This research plan is valid between 5/22/2011 and 6/26/2011, at which point an updated plan will be submitted.

Research Issues

Based on conversations with representatives of design, information architecture, product development, marketing, and customer service, we have identified five large-scale issues that our research will attempt to shed light on.

• While many people use the core product comparison service, less than 1% (based on analysis of tracking cookies) ever purchase anything from the online shop.

• While the top levels of the content tree get a fair amount of use, the deeper levels, especially the product-specific sections, do not.

• The competitors’ design is a lot less polished and much more chaotic, yet they get twice as much traffic with a similar amount of advertising.

• Other than knowing that they’re comparing one product against another, there’s little information about the circumstances under which people use the service.

• People often complain about being unable to find a specific product again after they’ve found it once.

Research Structure

The research will be broken into two parallel segments: interaction research and a profile of the existing user population.

Immediate User Research

In order to provide actionable results in time for the next release, we will immediately begin a testing process to evaluate the existing site interfaces. This will determine which elements of the design work best, which are most usable, and which features are most compelling, while finding out what doesn’t work and shedding light on how users prioritize the feature set as a whole. There will be some competitive analysis included to uncover the strengths and weaknesses of the user experiences provided by competitors’ products.

The techniques used will include four rounds of usability testing and, potentially, some focus group research.

Usability Testing

We will conduct four sets of one-on-one structured, task-oriented interviews with five to eight users apiece from company X’s primary target audience, for a total of 20 to 32 interviews. The interviews will last about an hour apiece and will focus on how well people understand the elements of the interface, their expectations for structure and functionality, and how they perform key tasks. Video recordings of the interviews will then be analyzed for feature use trends and feature preference. There will be one round per week from 6/5 until 6/26. For each round, a report summarizing findings will be prepared within two to four business days of the completed research and presented to appropriate parties within company X. Each round will use the most recent prototype and will concentrate on the most pressing user experience issues at the time as determined by company stakeholders and previous research.

A fifth set of tests will be of the same format with the same tasks, but will be conducted with the services provided by Company Y and Company Z.

Focus Groups

If no additional usability testing is needed before launch, we will conduct a series of three focus groups with six to eight users apiece from two key segments of the user base, member researchers, and shoppers (as defined in the market segmentation studies obtained from marketing). These groups will concentrate on uncovering what the users consider to be the most valuable parts of the service and where the service performs below their needs and expectations.

In addition, a competitive focus group will be conducted with users familiar with Company Y’s product discussing that company’s product.

Existing User Profiling

In addition, we will begin a program to create a profile of the existing user base and to better understand how they comparison shop. This will (we hope) uncover opportunities for the service to expand into and provide a closer fit to people’s lives, further encouraging its use.

The technique used will be site visits with one to two team members.

Site Visits

We will visit the homes or offices of three to five people representing a couple of the primary target audiences. We will schedule the visits for times when they expect to be comparison shopping for a specific item, and then we will observe and document (with video recording and handwritten notes) how they go about this task. We will create a model of the process they use to comparison shop based on analyzing the video and notes, enumerating what tools and techniques they use, what problems they face, and how they solve them.

Schedule

The following schedule lays out the planned research. Most work is done in parallel between several different tests in order to get the most research in the available time. The usability tests all involve about the same amount of preparation and recruiting, which can happen simultaneously for one test as the next test is being conducted and analyzed.

Focus groups involve a fair amount of preparation, but since the groups themselves are relatively short (two hours apiece), they can all be conducted in the same week (although the schedule allows for a week’s slippage for the last of the regular focus groups). There’s also a competitive focus group, which has its own deliverable.

The site visits are not slated to be completed in this time period because it was determined that although understanding the use of the product in context is very important, understanding immediate usability needs is a higher priority. Thus, the schedule displays preparation for it, but lists no deliverables.

Budget

These are the projected budgets, broken out by total estimated time and total estimated costs. These are approximate figures based on experience, and they will be adjusted in future research plans to reflect actual amounts as the research progresses.

Five Usability Tests

| Preparation | 10 hours |

| Recruiting and scheduling (assuming 40 participants—32 regular and 8 competitive) | 80 hours |

| Conducting tests | 120 hours |

| Analyzing tests | 80 hours |

| Writing report and presenting results | 15 hours |

| Integrating with development (meetings, presentations, etc.) | 10 hours |

| Total time | 315 hours |

| Recruiting incentive (25–40 people) | $2500–4000 |

| Supplies (food, videotape, etc.) | $500 |

| Total cost (not counting salary) | $3000–4500 |

Deliverables

The results of each usability test will be sent in an email as they are completed. Each email will include an outline of the procedures, a profile of the people involved, a summary of all trends observed in their behavior (as they apply to the initial research goals), problems they encountered, and a series of supporting quotations. A presentation of the results of each test will be scheduled for everyone affected. The presentation will allow the analyst to answer questions about the results and give further explanations of the proceedings of the test.

The results of all the regular focus groups will be collected into a single report, which will be sent by email as soon as it is complete. In addition to outlining the procedures used and providing a summary of the trends as they apply to the research goals, it will analyze any differences observed between various market segments. There will be a separate report from the final focus group that will compare the values and reactions of users of Company Y’s services to those observed with Company X’s.

Maintenance

It’s important to revise the research plan every time new knowledge comes in. Everything is subject to change as your team and the company’s understanding of the user’s experience grows. Re-evaluate, refine, and rewrite research goals to take every piece of additional knowledge into account. During particularly fast-moving periods in your company’s or product’s evolution, you may need to plan in detail for the short term, but keep long-term research planning more open-ended.

Since every piece of research is likely to affect your understanding of a number of different research goals, all knowledge about the user experience should be consolidated whenever possible. A good way to do this is to create a wiki site that contains all the reports and goals and that links each goal to the information that applies to it, and to enter all problems into the development group’s bug-tracking software.

Eventually, you should have a set of interlinked documents that, together, make up a more-or-less complete picture of your user population.