Chapter 7

Focus Groups

Focus groups are structured, attentively moderated group discussions that reveal a target audience’s conscious preferences, recalled experiences, and stated priorities. They can tell you what features people value the most and why they value them. As a competitive research tool, they can uncover what people like best about competitors’ products or services and where those products and services fail. Sometimes they even reveal entirely new competitors or applications for the product or service.

Originally called “focused interviews,” focus groups emerged as a social research method in the 1930s, gained strength as a way to improve soldiers’ lives during World War II, then finally took center stage as a marketing tool in the 1950s. As such, they’re probably one of the oldest and most widely used techniques for researching the user experience.

Sometimes vilified as shallow and misleading, focus groups do not deserve their bad reputation. Focus groups are not a cure-all for bad products, but neither are they necessarily pseudoscientific voodoo. When guided by a good moderator, carefully analyzed, and appropriately contextualized, they are an excellent way to uncover what and how people think. In particular, they can reveal what people believe about themselves and their needs, which is crucial in determining how to present a product to the public.

Digital product development generally employs focus groups early in the development cycle, when generating ideas, prioritizing features, and understanding the needs of the target audience are paramount. As a quick way to hear a lot of personal stories in a short time, focus groups can give development teams an early foundation from which to analyze the product and its users’ needs. Watchable and jargon-free, they engage company members who might not otherwise have the opportunity, expertise, or time to participate in user experience research.

Focus groups are popular in part because they are efficient. Two people working part time can set up a series of groups, run them, analyze the results, and have a report in three weeks. Conducting interviews with a similar number of participants, however, can take a full-time researcher almost twice as long. A survey would need to sample a much larger number of people—significantly increasing the complexity of the logistics and analysis, while providing less understanding about the motivations and attitudes of the respondents. And reading forums, blogs, and other sites of customer feedback doesn’t provide the same opportunity for immediate, face-to-face questioning and conversation between company representatives and customers.

That is not to say that focus groups can neatly substitute for other techniques described in this book. By taking people out of their usual environments and putting them in a conference room, you are inevitably going to miss something. Focus groups cannot take the place of usability, in-context interviews, and diary studies. It’s not wise to invest expensive resources based solely on self-reported beliefs and preferences. But with careful preparation focus groups provide an opportunity to see the world from the perspective of your users quickly and relatively cheaply.

When Focus Groups Are Appropriate

Knowing when to use focus groups is one of the keys to using them successfully. Although the technique is straightforward and flexible, it’s not applicable to all cases or at all stages in the development of a product.

What Focus Groups Are Good For

Focus groups are good at finding desires, motivations, values, and memories. A focus group is an environment where people (ideally) feel comfortable revealing their thoughts and feelings. This allows them to share their view of the issues and assumptions that lie at the core of an experience and to relate them to real-world situations. The hallmark of a good user experience focus group, in fact, is concreteness. Knowing people’s preferences and options is only helpful when you know where those beliefs come from.

Focus groups for user experience design (as opposed to focus groups for marketing existing products) are generally scheduled early in product development, though they can also be done during redesign or update cycles. That’s when the development team is trying to nail down what problems their product is supposed to solve, how it’s supposed to solve them, and why it’s valuable for consumers to use their solutions versus all others. Likewise, by bringing users of competitive products in early in the process, it’s possible to find out why people value the competition, what they feel are the most critical features, what regularly bothers them, and where they feel the competitors fail.

In combination with imaginative techniques such as probes, collages, and mappings (discussed in Chapter 10), focus group moderators can prompt a concrete, detailed discussion about products and services people want in their lives. Focus groups can also contribute to competitive analysis, allowing you to examine preferences and attitudes quickly across a range of products. Apart from the obvious marketing angle, this information can immediately influence feature and interaction development, defining a user experience that’s closer to what the target audience wants before resources have been committed. Focus group data can (and usually should) be verified, either through a generalizable survey or through more in-depth and rich interviews or observation. However, identifying trends often gives teams enough data for initial decisions.

Later in the development cycle, the technique can help identify and prioritize features. Bringing a working prototype, visual mockups, or a concept video to a group discussion is a quick way to get feedback on a design direction before too much time and money are invested. Knowing why people value certain features and how they respond to what you present can help determine what gets developed and in what order. Moreover, since focus groups can act as brainstorming sessions, it’s possible to achieve a synergy in which participants generate more ideas together than they could have come up with on their own.

One example from Elizabeth’s practice was a tablet computer designed specifically for hospital nurses. She had a number of different designs for the tablet and needed to provide some data to help the product team choose between them. She knew that there were many different kinds of nursing tasks, and that an emergency department nurse might have different needs than an intensive care nurse. But she didn’t have time to individually interview nurses from each major professional specialty. She just needed to know which design direction might be broadly acceptable to the widest number of nursing specialties, and, crucially, why. So she conducted three focus groups with six nurses each, representing as many different professional specialties as possible. In each focus group, she had the nurses discuss differences and similarities between their jobs, and then had them review five different form factor prototypes.

Through the discussion of nursing jobs, she discovered that the tools for nursing roles from telemetry to pediatrics needed to survive rough treatment. The participants shied away from equipment that seemed fragile. They wanted tools that could be quickly dropped if they needed both hands for patient care. Busy with paperwork, patients, and medication management, nurses in the study were impatient with tools that didn’t work right the first time. Based on the focus groups, the team focused on designs that could be carried in one hand and made sure that programmable buttons provided quick access to frequently used functions.

Focus groups uncover perceptions. This does not mean that they uncover what people actually need or what their actions show they really value. Focus groups will only tell you what people will say they need and what they claim they care about. However, relativism aside, learning what people believe about themselves is as important as knowing what, in practice, they do and feel. Designers, product managers, and marketers need to take people’s self-perceptions seriously in order to effectively communicate the product’s function and define a style for the product that is recognizable and memorable. The closer a product’s presentation of its services matches people’s perceptions of their needs, the more they’re likely to use it.

What Focus Groups Are Not Good For

First and foremost, focus groups are not a way to understand what people actually do. There’s no way that people can predict whether they will actually want to use a product, service, or feature in practice, or whether they will even be able to use it effectively. That’s why we have usability, observation of products in use, and diary studies.

Second, focus group results do not generalize to a larger population. They can’t replace surveys. Data from multiple focus groups can help you make models of human perceptions and attitudes that may well apply to people similar to the participants. However, in almost every case, focus groups are not statistically significant samples. This concern cannot be overstated. When survey samples are both representative and statistically significant, their results can apply to larger populations. There’s no guarantee that the proportion of responses in a focus group matches that of the larger population of users.

When taken literally, statements made in focus groups can mislead analysts. Just think of the many products (such as many feature films) that get worse, rather than better, by literal application of focus group results. Here’s a funny, if potentially mythical, example from the history of comic books. In an attempt to give Superman fans what they wanted, a focus group of 10- to 12-year-old comics readers was asked what kinds of stories they liked. For a while in the 1960s, Superman’s plot lines followed the kids’ requests slavishly. What followed was surreal: the Man of Steel dressing up as a Native American and meeting George Washington, not to mention the transformation of Jimmy Olsen, a meek sidekick, into a giant space turtle. In the end, it led to creative bankruptcy. The impossibly convoluted storylines had to be scrapped entirely, and the comic started over as if none of the stories had happened. The lesson: People do not always understand the implications of what they request. They may not understand the trade-offs necessary to accomplish what they ask for. And they can’t always accurately predict what they’ll enjoy or find useful in practice, as the Superman writers discovered.

Four Types of Focus Groups

There are four common types of focus groups in user experience research. The type of group you choose depends on the types of questions you want to answer, which in turn will likely depend on the stage of development the product is in. Don’t feel limited by these categories; they’re provided only as rough guides.

Exploratory

These groups get at general attitudes on a given topic, helping developers see how the eventual users of the product will understand it, what words they use to talk about it, and what criteria they will use to judge it. For example, a furniture company is interested in what criteria people use to buy furniture in stores and how they buy similar items online. At the beginning of their development process, they run focus groups and find out that, at first, people insist on seeing furniture “in real life” before buying it (thus negating their entire business plan for selling it online). Further discussion reveals that it is only certain classes of products such as couches and beds that are mistrusted without direct experience. With other things (chairs, tables), most people have no problem buying based solely on pictures and descriptions and, in fact, would prefer to do so.

Feature Prioritization

These groups determine the features that are most attractive to the group and why. They are held, in general, right after the beginning of the development cycle, when it’s already clear what the general outlines of the product are going to be. In these types of groups, the assumption is that the participants are interested in a certain kind of product, and the discussion centers on what kinds of things they would like that product to do for them. For example, the participants in a focus group for a homepage creation service were not nearly as interested in community services as they were in tools to help them build and market their own homepage. The “community feeling” that the site was trying to communicate and the tone with which it promoted itself meant little. For them the value in the site lay in the tools and free disk space.

Competitive Analysis

Just as it’s important to know what people value in the feature set that a product provides, it’s important to know what attracts and repels them with respect to competitors’ sites. Often held anonymously (with the commissioning client left unmentioned), these focus groups attempt to understand people’s associations with a competitor, what aspects of the competitor’s user experience they find valuable, and where it doesn’t satisfy their needs and desires. For example, a competitive focus group of online technology news sites revealed that people saw non-news content as largely superfluous. Most read only one news site for a few minutes a day. They valued daily updates and links to other sites, not opinions or in-depth background stories.

Trend Explanation

After spotting a behavioral trend, whether from survey responses, customer service feedback, or website analytics, it’s often difficult to determine its primary cause. Focus groups can help explain the behavior by investigating the users’ motivations and expectations. These types of focus groups are generally held either as part of a redesign cycle or in response to specific concerns. For example, a survey showed that parents of babies bought more children’s products online than parents with older children. Focus groups with people who had taken the survey discovered that parents with babies liked to do their shopping when their babies were asleep, which was often after local shops closed. Older children were more mobile and had preferences of their own, so parents might look for sales online, then take the children in person to help make choices.

How to Conduct Focus Groups

Before you launch a focus group series, it’s important to determine several things.

• The topics that you want to research. Not all groups feel equally comfortable talking about all subjects, and not all subjects lend themselves to group discussion.

• The target audience. These are the people you’re going to invite. Specifically, you need to determine the subset of the target audience likely to give you the best and most relevant feedback.

• The scope of your research. Focus group series can have a few groups of a handful of people or as many as a dozen groups with ten or more participants apiece. The number of groups and people will depend on the complexity of your questions, the depth to which you want to explore the answers, and the certainty with which you want to know these answers.

• A schedule. The best results come from planning for likely contingencies. A good schedule (see Table 7.1) provides sufficient time for everything, especially recruiting, guide writing, and enough flexibility to be able to make a mistake or two.

Table 7.1. A Typical Focus Group Schedule

| Timing | Activity |

| t − 2 weeks | Determine audience and scope; start recruiting immediately. |

| t − 2 weeks | Determine broad topics to be investigated; start writing guide. |

| t − 1 week | Write first version of discussion guide; discuss exact topic wording with development team; check on recruiting. |

| t − 3 days | Write second version of discussion guide with timing; discuss with development team; recruiting should be completed. |

| t − 2 days | Complete guide; schedule run-through; set up and check all equipment. |

| t − 1 days | Run through in the morning; check times and adjust guide questions as appropriate; do final recruiting check. |

| t | Conduct groups (usually one to three days depending on scheduling); discuss with observers; collect copies of all notes. |

| t + 1 day | Relax; do something else. |

| t + 3 days | Watch all tapes; take notes. |

| t + 1 week | Combine notes; write analysis. |

A typical focus group series takes about three weeks from beginning to end.

Choosing Topics

For an average focus group, you should have three to five main topics to investigate. These should be phrased in terms of the project as a whole. “Understanding the mental model people use when researching insurance” could be a goal for an insurance brokerage site, while a service that recommended home building contractors could be interested in “Knowing at which point people turn to an external service when doing home repair.” A high-end online auction site doing a competitive analysis could have “Understanding what repels high-end car sellers from listing their cars on eBay” or “Uncovering what factors will help our product idea to be seen in the same class as Sotheby’s” as two of their goals.

Not all people are comfortable talking about all topics. Choose questions that your target audience will be comfortable discussing. Different audiences for the same product may react differently to the same topics.

A group should be able to adequately discuss each topic in about ten minutes. Topics should be broader than the actual questions you will ask participants, and they should not be goals that are better accomplished by other means (such as a survey). “Making a list of our competitors” would generally be too broad and probably better answered by a survey, whereas “Discovering what factors make the user experiences of our competitors more compelling than ours” is probably more appropriate.

Picking a Target Audience

It is not the actual differences between participants, but whether they perceive each other to be different, that determines their willingness to discuss a topic together.

David L. Morgan, Focus Groups as Qualitative Research

In focus groups, maybe more than in any of the other methods in this book, careful selection of participants is crucial. For people to feel comfortable talking about their experiences and their values, they need to know that other people in the group will not judge them and that they are with other people like them. Thus, unlike most other kinds of research, focus groups usually rely on homogeneous audiences.

However, the definition of “homogeneous” depends on the context of the research and the group. The participants don’t need to be the same in every way, just in the ways that allow people to talk freely about their experiences. For example, generational differences can keep a group from completely opening up about their musical tastes, but might be comfortable and even desirable in a conversation about kitchen appliances.

From your ideal target audience, you should choose a subset or several subsets that are likely to give you the most useful feedback on your topics. The right group will vary from situation to situation. First, you need a solid profile of your target audience, backed up with information about their demographics and technology use. For example, if you’re just looking to find out what existing users value about your service, you want to pick the people who represent the largest subset of your actual audience. However, if you’re looking to find out why your service has problems retaining customers, you must be much more specific: you must focus only on the people who are just like your standard population but have used your service once and never again.

Often, it’s useful to choose several groups to get an understanding of the breadth of experience and as a way to concentrate on specific groups’ experiences. For example, if doctors are supposed to use your system but only medical students seem to be using it, then you probably want to talk to both groups. The doctors will tell you why they don’t use it, and the medical students will tell you why they do. Maybe you need two separate focus group series.

Define “similarity” from the perspective of subgroup members. If you believe that certain groups of people would not feel comfortable chatting, then don’t put them together. Start with demographics and technology use. Income, race, sex, class, age, job, and level of technical know-how are just a few of the factors that can play a role in group interactions and their reactions to a product or service. In order to create a group that can comfortably discuss the topic, we have to take these differences into account. Once the basic outlines are defined, further divide the groups based on behavior: Who does what? What else do they do? Sometimes differences that matter in one topic don’t in another. Just remember: you are not looking for people who think identically—you are looking for people who will likely feel comfortable sharing different opinions and experiences.

Here are some examples.

• When studying automobile buying, researchers learned that men sometimes dominate conversations about cars in mixed-gender groups. Since the researchers wanted to ensure a diverse conversational mix, they created three groups: men, women, and a combined group.

• A medical service decided that doctors and doctor-administrators would likely have trouble feeling comfortable with each other because of their roles in the hierarchy of a hospital—even though they would likely both use the service. Thus, the focus groups were divided based the amount of time each participant spent on administrative work.

• A mobile interface to sports media decided that people living in the San Francisco Bay Area would be likely to see a disproportionate amount of information about new technologies when compared to seemingly similar people elsewhere in the United States. Research was conducted in Washington, DC, and St. Louis, Missouri.

You should feel free to define the subgroups in whatever way you feel comfortable. However, do not define subgroups based on the opinions or preferences of their participants. Prescreening participants for their previously stated values defeats the core purpose of the focus groups, which is to explore those values. For example, don’t screen for people “who like shopping online”; instead, focus on people who shop online and then determine the full range of reasons why these people shop—especially if they don’t enjoy it very much.

Recruiting

Once you’ve picked a target audience (or audiences), it’s time to find participants and invite them. Recruiting for focus groups, much like recruiting for other kinds of research, should be done early and should begin as soon as you’ve picked your audience.

A couple of things distinguish recruiting a group of people from the standard recruiting process described in Chapter 6, which concentrates on finding individuals.

• The exact profile of the participants is more important. With much research, it’s possible to have participants who are almost, but not exactly, ideal target audiences. With focus groups, it’s critical that all the people in a given group fall into the desired profile since one person outside it can derail a whole discussion. Owners of small shops, for example, could potentially feel uncomfortable discussing their problems and feelings with an owner of a large store or a franchise.

• Never recruit people who already know each other. Friends—or even acquaintances—unbalance the group discussion dynamic. A raised eyebrow or a sigh says a lot between two people who know each other and can disrupt the discussion and inadvertently conceal important information. When recruiting using the friends and family method, avoid recruiting people who were all referred by the same person.

• Avoid people who frequently participate in focus groups. The group discussion depends on unguarded responses. Veterans of the process may attempt (often subconsciously) to give the kinds of answers that they feel are expected, or they may try to predict the next topic of discussion. Although not fatal, this can skew the discussion, necessitating extra moderation and analysis. If you have to recruit people with focus group experiences, the experience should be neither frequent nor recent. For these same reasons, never include people who work for organizations that often employ focus groups. So no marketing company employees, no advertising agency people, and so on.

• Make sure none of the participants have significantly more knowledge about any of the topics than the others. If there’s an “expert” in a group, that person’s knowledge can intimidate the other participants, and his or her views can bias the whole group’s perspective. Of course, an entire focus group of experts can be very worthwhile.

• And obviously, make sure you don’t recruit anyone employed by any of the specific companies you’ll be talking about!

Once you’ve decided your target audiences, write a profile of the kind of people you want to recruit. The following could be a profile for potential users of a home improvement recommendation website. It defines a group of people who are actively thinking about home improvement and would be likely to look for information about it online.

A Sample Focus Group Recruiting Profile

Demographics

Ages 20–55

Income not important if behavior criteria are met; otherwise, $70K+ household

Gender unimportant, as long as primary decision maker

Web Use

Use Internet at home or work

Use Internet on computer or mobile phone

Have 3+ years of Internet experience

Use the Internet 5–10 hours per week for personal tasks

Shop for products

Compare products or services

Visit websites that indicate an interest or need for home remodeling (e.g., DIY Network, House Beautiful, Martha Stewart.com)

Behavior

Have completed home improvements in the last 9–12 months or intend to perform improvements in the next 3 months

Total improvement cost at least $20K (estimated if in the future)

Defining Scope

You need to decide two things when determining the scope of the focus groups you’re going to run: how many groups you’re going to have and how many people you’re going to have per group.

Never hold only one focus group for the same reasons you shouldn’t base conclusions about a class of people on the words of a single person: there may be factors that seem important to the group but that turn out to be the product of the dynamics of one specific group of people. That said, more than four groups is rarely necessary. The first group is, essentially, a dress rehearsal. By the third group you should see confirmation of the views and statements (sometimes verbatim) from the first two groups. The fourth group should confirm trends in the first three. If there is still a lot of new information (especially dissension) coming in during the fourth group, it may be a sign that further groups are necessary or that the makeup of the groups is too broad.

Likewise, User experience research focus groups are generally smaller than their traditional marketing counterparts. Walking through a scenario, demonstrating a prototype, or having people perform a collage or mapping exercise takes time. Asking people for detailed responses—and then explanation of their responses—to these kinds of stimuli takes more time. Encouraging conversation takes even more time. Reducing the size of the group can help the moderator avoid a rushed and superficial discussion. Six to eight is a good size, balancing the collection of fine detail with a breadth of perspectives. In cases where you’d like to get a lot of depth from each participant, or if the individual focus groups are short, it may be useful to reduce the number to four. Use fewer than that, and the discussion feels more like an interview and doesn’t produce as dynamic a situation.

See Chapter 8 for more information on collaging, mapping, and other creative techniques for user experience focus groups.

Writing a Guide

The discussion guide is a script for the moderator to follow. It creates a consistent framework and a schedule for the focus group series. Groups hear the same questions in roughly the same order with much the same context, and all the topics are given enough time. This allows a discussion to bring out the subtleties of the participants’ views without shortchanging any of the topics.

Focus group questions should be:

• Carefully ordered. Questions put the participants in a certain frame of mind, thinking about certain issues and remembering certain events. A careful sequence of questions takes advantage of that frame of mind to make the flow of the group discussion feel more natural, which in turn helps the participants to maintain a creative stream of ideas and produce better insights. In general, questions should run from the most general to the most specific, with each question narrowing the discussion a bit and concentrating on a subset of what was discussed before. Plan transitions between topics unless a brand new topic is introduced and discussion begins from a general question again. In order to help the group achieve some comfort with each other before creating any friction, you will generally want to move from questions likely to produce consensus to more controversial topics.

• Nondirected. As described in Chapter 6, questions should not imply an answer or a value judgment. They should focus on allowing the participants to fill in their own thoughts and values. For example, asking, “Do you think Microsoft has a better search engine than Google?” assumes the participant thinks there are advantages of one over the other. Instead, the question should be framed neutrally: “Are there any things you like about using the Google search service? Are there things you like about using Microsoft? What are they? Are there any ways in which you can compare them? How do they compare?”

• Open-ended. Questions should not constrain the answers to fixed responses. They should encourage people to open up and share experiences. Longer responses tell a greater part of the story and tend to be less ambiguous than shorter responses. Thus, rather than phrasing a question in the form, “What’s your favorite recipe site?” you could ask, “How do you search for recipes online?”

• Focused on specifics. The questions should encourage the participants to be specific in their answers. Richard A. Krueger, in his book Focus Groups, recommends breaking down “why” questions into multiple “what” questions, explicitly asking for the influences that informed participants’ decision and the attributes of their decision. For example, “How did you decide to go shopping online for forks?” and “What factors went into picking this site?” will provide better insight than asking, “Why did you pick this site?”

• Personal. People often attempt to generalize their experiences to the general public or some larger hypothetical group. Since you want to know individual views, values, and experiences, emphasize individual experiences. Questions should be formulated to concentrate on people’s current behavior and opinions, without presenting the option to project their experiences. Thus, “If you had to redo your kitchen right now, which of these features would you use to find a home contractor?” is preferable to “Which of these features do you think are useful?”

• Unambiguous. There should be as few shades of meaning as possible, especially when the participants are introduced to new terminology.

Granted, fulfilling all these criteria with all questions is often difficult (writing questions that are simultaneously specific and open-ended is a particularly tricky challenge), but they should be kept in mind as guidelines that should be followed whenever possible. Next to carefully selecting participants, writing a clear, thorough discussion guide is the most crucial ingredient in a successful focus group.

Sample Discussion Guide

The guide is broken up into three major sections: the introduction, the main discussion, and the wrap-up.

The guide that follows is from a focus group for an online news site that is (primarily) interested in understanding the criteria its existing users use to pick the news sites that they read.

Warm-up and intro (10 minutes)

The introduction sets the tone for the discussion, breaks the ice for the participants, and explains the process. It’s important to explain who you are—and especially that you are not personally invested in the project. Many people will not want to say negative things if they worry about hurting your feelings.

Hi. Welcome.

My name is [first name]. I am a researcher working with [company], who have asked me to help them get some of your thoughts and opinions about some products and some ideas they have. I am not associated with the development of any of the products we’ll be talking about, and I have no emotional attachment to any of these things, so you can say whatever you want.

We invited you here because you all read a fair amount of news online. What we’re going to do today is talk about some of your experiences so that they can create a service that is best tailored to people like you.

Telling people how they were chosen helps them feel comfortable with one another. Informing them of the end goal of the research helps them start focusing their thoughts.

The discussion is going to be a pretty casual conversation, but there will be a couple of times when I will ask you to concentrate on certain things.

While we’re talking, it’s important that you be as candid as possible. You won’t hurt anyone’s feelings with anything you say, so please say exactly what you feel.

Furthermore, we want your opinion. No opinion is right or wrong here—especially about the things we’re going to talk about—it’s just an opinion, so even if you disagree with someone in the room we’d like to hear that.

But, we’d like you to speak one at a time.

Set out the ground rules for conversation ahead of time and explicitly allow disagreement. This encourages people to feel comfortable voicing their thoughts later.

Also, since we have a lot of ground to cover today and none of us want to be here for hours, I may have to ask you to wrap up a thought or put it aside so that we can move on.

People don’t take being interrupted as personally if the expectation has been set early on.

Behind that glass wall, as you can imagine, are a couple people from the company whose idea we’ll be talking about and [assistant moderator’s first name], who is working with me. Occasionally, [assistant moderator’s first name] may come in here with a note or something we need. Regardless, feel free to ignore them.

Explicitly noting the mirrored wall (assuming there is one in the room) helps to diffuse any anxiety participants may have about it. Sometimes it’s even appropriate to have the participants wave or make faces at the people behind the mirror during the introduction. Once mentioned, it shouldn’t be brought up again.

As I said, we brought you here to hear what you think, so you won’t hurt anyone’s feeling by whatever you say. We are video recording this conversation, in case you’re wondering, so that [first name] and I don’t have to sit here scribbling notes and can concentrate on listening to you. It’s purely for research purposes. It may be seen by members of the product development team, but it’s not for any kind of publicity or promotion or broadcast.

If the session is video recorded, that should be mentioned, even if participants have signed a consent form before the focus group began.

Now I’d like to read you what’s called a statement of informed consent. It’s a standard thing I read to everyone I interview. It sets out your rights as a person who is participating in this kind of research.

As a participant in this research:

You may stop at any time.

You may ask questions at any time.

You may leave at any time.

There is no deception involved.

Your answers are kept confidential.

Here is a form that gives us permission to video record this discussion and to use the recording in our research.

It’s critical to inform participants of their rights and to get releases that allow you to video record them. Don’t skip it. Doing otherwise is both unethical and, in some situations, illegal. Don’t be dour when introducing the camera, however, since it can create an overly formal atmosphere. Mike usually makes a joke at this point by saying (while pointing at the snack dish that is in virtually every focus group room) that we’re not doing a secret candy taste test.

Any questions about any of that? [Pause for about 3 seconds to let people speak] Let’s start!

Now I’d like all of us to introduce ourselves. By way of introduction, I’d like you to tell us four things.

Your first name

Which city you live in

What TV shows or publications you absolutely can’t live without every week

Anything that regularly irks you about the Internet

(Assistant moderator and moderator do introduction first, everyone goes around.)

The introductory questions introduce everyone and break the ice by sharing something personal but not private, such as a favorite TV show or a pet peeve. As such, it’s appropriate for these questions to be specific, (somewhat) directed, and unrelated to the topics of inquiry.

General News Reading (20 minutes)

How do you get the news most frequently?

Probe: Are there some other ways you regularly get news?

Which news sites do you regularly read? (Make a list on the whiteboard.)

Probe: Are there some that you read more than others?

Probe: What attracts you to the sites you read more often? (Ask individuals about specific sites.)

Have you ever switched from one favorite to another? How often? Did it just happen once or have you had several favorites?

Probe: What made you decide to switch?

Probe: How did you pick the site you switched to?

Probes are follow-up questions that dig deeper into a given topic.

Switching gears, what kinds of news are there? (Make a list.)

Are there any good sites for sports? How about for politics? Technology?

Even though the primary topic is technology news, asking about several different kinds of news keeps the discussion from focusing on technology prematurely.

Are there sites that specialize in any of these (business, entertainment, technology)? Can you name some, even if you don’t read them regularly?

Changing gears again, have you ever come across a situation where you think that advertising has affected the news you’re reading?

Probe: Can you give an example?

Prioritization Exercise (20 minutes)

Pass out paper with the following exercise:

Rate each of the following things based on how important they are to you. Rate them from 1 to 5, with 1 being least important. Also, if you can think of a site that does that one thing better than any other site, write its name or URL next to the statement. You don’t have to put a different site down for every one, and you may not want to put any sites down for some.

The number of different stories on a given topic

The number of different topics covered

How quickly the page downloads

Who is presenting the news

How comprehensively each story is covered

Regular columnists

The quality of the site’s search engine

The visual appearance of the site

How quickly stories are covered after they happened

How easy it is to get around in the site

(Going around) Say which ones you picked as the most important.

Probe: What about it makes it so important?

Probe: Is there a site that does it well? Does anyone else have that site written down?

Are there any attributes of news sites that you think are important but that are not on the list?

This exercise is designed to start a discussion about what makes a good news site by focusing on specific features.

Competitor Site Review (20 minutes)

We’ve been talking about general news reading, but let’s talk about a couple specific news sites for a few minutes.

Turn on projector.

Are any of you familiar with (competitor site)?

Probe (for people who are): Have you ever read it? How often? Under what circumstances do you read it versus other news sources?

Describe [competitor site’s] personality.

Does [competitor site] fall into any kind of specialization?

What kinds of stories would you expect to find here?

Probe: Are there situations where you think you would read it versus other sites?

Probe: Are there kinds of technology news that you wouldn’t go here for?

Probe: What about columns? Are there any that would entice you to read them on a regular basis?

(Go through questions again for another competitor; present competitors in a different order to every group.)

Blue Sky and Wrap-Up (10 minutes)

We’re almost done. I’d like to do a quick brainstorming exercise. I only have one question, but I’d like everyone to think about it for a few seconds and say what comes to mind.

If you could have anything you wanted in a news service, what would you really like a news service to do that none of them currently offer?

(Wait 30 seconds, then go around and discuss, write ideas on board.)

All right, that’s the last of our questions about news.

I know you’re all excited about talking about online news, but we really have to wrap up. If there’s something you think of on your way home that you’d really like to tell us, please feel free to send a note to the following email address [write email on board].

I have one final question: is there anything that we could do better, either in terms of scheduling or in terms of running these groups? Should we have different food, whatever?

Once the content for the site had been established, subsequent focus groups concentrated on the desirability of specific features and how people use news sites in their daily lives.

After you’ve written the guide, it’s important to review it and time it. Members of the product development team, especially the product and project managers, are good guide reviewers. They can point out ambiguities, serve as a second perspective, and prepare the rest of the team for observing the groups.

Guides should always be tested. An easy way to test the guide is to get a couple of people (it doesn’t have to be as many people as the actual group) who haven’t seen it and walk them through it, paying attention to how they answer the questions and how accurate the timing is. In addition, treat the first group as a dress rehearsal, reviewing the effectiveness of the guide and adjusting it appropriately.

Setting a Schedule

A typical schedule (see Table 7.1) for a focus group should provide sufficient time for recruiting and writing the discussion guide.

Conducting the Group

The Physical Layout

Hold groups in a comfortable room with good ventilation, good temperature control, and few distractions. Make sure it’s large enough for the group, without being so big that people feel lost in it. Make sure that all the participants can see each other around the table and that there’s no obviously “best” seat. As well, make sure that the observation room (if there is one) is also comfortable. Hot, cramped, poorly ventilated rooms aren’t conducive to positive, engaged attention.

If a focus group runs for more than 90 minutes, give people at least a five-minute break halfway through—enough time to get to a restroom, call their families if it’s late at night, or check on their cars or bikes.

Typical setups look like conference rooms or living rooms, depending on whether the participants are supposed to feel they’re in a comfortable work area or at home. Actual conference rooms or lounge areas are easily converted to focus group facilities. If the groups are to be held in a conference room with windows to the inside of the office, the windows should be covered or the group should be held as far away from the windows as possible. Outside windows are fine, unless they’re on the first floor, in which case they can be too distracting.

After the group starts, no one except the assistant moderator should enter the room. (Post a sign on the outside door to this effect.) Mike once had a focus group interrupted by a pizza delivery. After some confusion, it became clear that the pizza was for the observers behind the mirror. Although the participants joked about it (“We don’t get pizza!”), the disruption set up an unfortunate dynamic. Even entrances and exits by the assistant moderator should be kept to a minimum, in order to avoid any such disruption to the flow of conversation.

Focus Group Supplies Checklist

Here’s a starter list for the basics you’ll need to bring to a focus group. If you are using a commercial research facility, they may be able to take care of many of these elements for you—check ahead to see what your facility will provide and what it will cost.

• Consent forms and incentive receipts

• Food and drinks for the participants and observers

• Supplies for any object-based activities (see Chapter 8), including big sheets of paper, markers, Post-its™, etc.

• Recording tools (video and/or audio), along with any accessories you need (e.g., batteries, power cables, tripods, microphones). Bring extra batteries just in case.

Less frequent, but still important, issues:

• Need a projector? Check to see whether your focus group room has one built in or if you’ll need to bring one.

• Planning to do some brainstorming or list making? Check whether your focus group room has a whiteboard. If not, you may have to invest in some poster-size paper pads and big markers. An easel is handy as well, so the whole group can see what you’re writing. You can also take notes by projecting from a computer screen, but paper is still more reliable, easier to set up, and more flexible.

Eating together can break the tension when people first meet, so provide food and drink when possible. For late evening groups, people are likely to have eaten dinner, so providing high-energy snacks (such as cookies) can often keep a sleepy group talking. Make sure to provide vegetarian choices and plenty of water. Crunchy food can be quite loud when recorded, so things like celery and potato chips are best avoided. Have plenty of noncarbonated drinks; people drinking carbonated beverages have a tendency to stay silent because they’re afraid they’ll burp in the middle of a sentence.

How to Create a Seating Order

Krueger recommends the following procedure to place people around the table:

• Print table tents with the participants’ names on them. Table tents are folded sheets of paper that sit upright on the table. Each participant’s first name is printed on both sides of the tent, large enough that it can be read from the observation room and on camera (1.5-inch letters printed in black seem to work pretty well).

• Identify the quiet and outspoken people by visiting participants in the waiting area and making small talk with the group.

• Figure out a placement for each person. Long-winded people go next to the moderator, so he or she can break eye contact without disturbing the group dynamic; quiet people go across from the moderator, so the moderator can make eye contact easily and elicit their comments.

• Organize the table tents according to this order.

• Then, when bringing people into the room, drop the table tents seemingly randomly on the table, but actually according to the predesignated order.

If observers are present, they will need some way to unobtrusively watch the proceedings. This can be the traditional two-way mirrored wall, with a soundproof room behind the mirrors that observers can sit in. The observer’s room should have its own entrance, so that observers can come and go without entering the discussion room. If such a room is unavailable, closed-circuit video is an inexpensive and easy solution. A long video cable and a television in a nearby room generally suffice, as long as the observation room is acoustically isolated from the discussion room. If the observers will not physically be on site, streaming video over the Internet will allow them to watch from multiple locations (see sidebar).

![]() Visit the book’s website at www.mkp.com/observing-the-user-experience for tips on remote observation tools, focus group consent forms, and other resources.

Visit the book’s website at www.mkp.com/observing-the-user-experience for tips on remote observation tools, focus group consent forms, and other resources.

Remote Observation of Focus Groups

In the past, observers had to be onsite to actively participate in focus groups. Now, using live streaming video and online messaging, observers need only an Internet connection to participate. While watching the video, they can send occasional questions to the assistant moderator as online chat or text messages.

At the time of writing, there are a number of paid and free services that simplify setting up a live video stream. However, since the easiest methods for streaming live video change quickly, we won’t specify any tools here. Suffice it to say that you will need to decide ahead of time:

• The number of connections to the video stream you are likely to have

• How high-quality your video needs to be

• Whether you will be recording the video stream or whether you will have a separate camera for the actual recording

• Also remember to test your video streaming setup onsite before your first focus group, giving yourself enough time to do any necessary troubleshooting. Setups that work perfectly in your office may fail in the field due to unexpectedly unreliable Internet access, hasty cable connections, and poor lighting.

Video record focus groups when possible. Unlike an audio recording, it’s easy to see who’s saying what on video and to see the body language that sometimes betrays a negation of a concept or discomfort with a topic. If the video process is made unobtrusive, it quickly disappears into the background of the conversation.

Only one camera is usually necessary to adequately capture a focus group, though you will need to take some care to get good audio. Place the camera roughly behind the moderator. If it has a good wide-angle lens, it’s not necessary to have a camera operator, which reduces the cost of the process, as well as the hassle and intimidation of having a person swinging a camera constantly between one side of the table and the other.

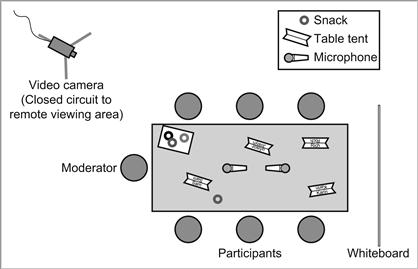

Two cardiod microphones are generally sufficient to capture all the participants’ comments without a lot of extraneous noise. Cardiod microphones are directional microphones that have a broad area of sound capture in front and a much smaller area facing back. Thus, unlike the omnidirectional microphones that are attached to most video cameras, they can be pointed away from sources of noise such as outside windows and air vents (see Figure 7.1).

For temporary setups (as in Figure 7.2), two opposing microphones set on the table work well. However, they’re vulnerable to vibration (a pencil tapping, a coffee cup being set down, or a computer humming will sound much louder to the microphone than they do in the room). Putting some cloth or a mouse pad between the stand and the table can ameliorate this problem.

Figure 7.1 Cardiod versus omnidirectional microphone sensitivity.

Figure 7.2 Temporary conference room-style focus group layout.

The Moderator

Focus group moderation is a skill. The moderator must encourage participation, without allowing any one person to dominate others. To do this without biasing the results takes practice, aptitude, and the right frame of mind.

The basic skills that a moderator must have are a respect for the participants, the ability to listen closely, and the ability to think fast. Often, a moderator must be able to predict where a conversation is headed and either drive it that way or move it in a more desired direction, without the participants realizing that they are being moderated. This can involve many subtle cues in what the moderator says, the tone he or she uses, and even his or her body language.

More specifically, the moderator must be:

• Always in control. Most of the time the moderator can use body language and verbal emphasis to maintain control, subtly directing the discussion to certain participants and topics. However, if a digression is moving in an unproductive direction for too long, the moderator should not hesitate to exert more overt control and refocus the discussion on the necessary topics. For example, if in the course of discussing home renovation services, the discussion digresses into stories about home renovation disasters, the moderator should refocus it on the product rather than on extraneous gripes.

• Always moving forward. The moderator should monitor the flow of the conversation and introduce topics at appropriate times, making the transition feel natural rather than controlling the flow by stopping discussion or abruptly changing the topic. That way the discussion doesn’t turn into an interview, with the participants answering the questions the moderator poses, one after another.

• Nonjudgmental. The moderator acts as mediator, helping the participants express their views without stifling their eagerness to do so. Therefore, the moderator should not express his or her views but facilitate the views of the group to come out. This sometimes involves suppressing the habits we have learned in maintaining civil conversation. For example, many people nod while someone is talking as encouragement, whether they agree or not. This communicates agreement and an endorsement of the viewpoint being expressed. Since the moderator is seen as the “official” at the table, the participants may feel that this is an authoritative endorsement of a certain position and may feel uncomfortable voicing a dissenting opinion.

It’s impossible and almost certainly unhelpful to remain completely immobile, of course. However, it can be a good exercise to limit extraneous nods, shrugs, and smiles at first.

• Respectful. The moderator must have the utmost respect for the participants at all times even if he or she does not agree with them. Every participant in a focus group has a perspective that’s useful to the development team, even if it doesn’t match with the team’s views. For all participants to feel comfortable speaking their minds, they need to know that the moderator will treat their input as valid as everyone else’s. This can be accomplished through the use of nonjudgmental statements and strict control of body language, but it’s best communicated through the honest belief that everyone needs to be heard.

• Prepared. The moderator should know enough about the topics discussed to be able to follow up on participants’ statement with specific questions. This does not mean acquiring expertise in the subject matter, but the moderator should have a good working knowledge of the general concepts, the terminology, and the implications of the issues being discussed. The moderator should also have some knowledge of the habits and environment of the people in the group.

In addition, the moderator should have a good sense of timing (knowing when to transition from one participant and one topic to another), a good short-term memory (referring to people’s earlier statements and using their own words to describe concepts), and an aptitude for diffusing uncomfortable situations, preferably with humor.

The Assistant Moderator

Although it’s certainly possible to conduct a focus group without an assistant moderator, having one helps the process.

The assistant moderator is a key analyst and the connection between the focus group and the outside world. The assistant takes care of the needs of the focus group participants and collects information, leaving the moderator to focus on maintaining a productive discussion.

Before the discussion begins, the assistant should greet the participants when they first come in, bring them into the discussion room, present any initial paperwork (such as nondisclosure agreements), and bring them refreshments. As the discussion progresses, the assistant can bring in notes from the observers and take care of requests.

During the discussion, the assistant moderator should take extensive notes on the interesting parts of the discussion (such as key quotations, issues voiced by the participants, and his or her own observations) and manage the observers’ discussion (taking notes on that, too). After the group ends, the assistant moderator can use these notes to spur a debriefing with the observers and the moderator.

Sometimes it’s useful to have multiple moderators. If there are a lot of groups, or they’re particularly long, or they’re done in different languages, it’s sometimes useful to use several people as moderators. If multiple people are going to be moderating, it’s important that they go through every question and determine how they’re going to ask it and what they will probe.

If there is no assistant moderator, the burden of moderating the participants, managing the observers, and analyzing the final results can fall on a single person. In such situations, it’s useful to create situations where the moderator can leave the participants alone for five to ten minutes and walk back to the observation area to review the discussion with the observers, helping frame the discussion for them.

Moderating the Discussion

Moderating a discussion is the process of balancing the participants’ comfort level and keeping the discussion producing useful information for the research. There are few strict rules for how to moderate a discussion since every group and every topic will demand a different approach Different moderators have different styles that work equally well.

There are, however, several general guidelines that apply to most user experience focus groups.

Actively Manage Group Dynamics

Spending five minutes chatting with participants ahead of time will give you a sense of social relationships—especially the participants who might be too quiet, too bossy, and so on. You can also have the assistant moderator do the talking and discreetly brief the moderator ahead of time.

During the discussion, check for people who talk too little or too much. Are silent people feeling shy? Intimidated? Bored? Try calling on them by name in order to demonstrate your interest. When you ask a general question to the group, look directly at any silent people to let them know you’re listening. At the same time, make sure certain people don’t talk too much. When someone is having trouble articulating an interesting idea, try judiciously interrupting with follow-up questions. When people are just talking without a purpose, ask them to conclude so that you can ask a different question: “This has been interesting, but we do need to move on to the next topic.” Calling on new people by name can also help you derail an overly talkative participant.

One dominant or bullying participant (also known as an “Alpha Jerk”) can ruin a whole focus group. Ideally, the best way to avoid the problem is to remove him or her before the group starts. Hostility or aggression can be obvious when meeting and observing participants in the waiting room. During the group, if the bully obviously tries to take “control” of the group from the moderator, it’s critical to draw attention away from the challenger. The techniques are basically the same as for a talkative person, but they need to be applied more firmly (and, often, more frequently) than for someone who’s merely wordy. In addition, physically dominating the discussion space by walking to a whiteboard and taking notes helps to regain the floor and control of the discussion.

Sometimes the conversation falls dead. To avoid this, try keep the energy level high. Mix in different types of activities, such as watching videos, filling out questionnaires, or using some of the object-based techniques from Chapter 8. If it seems like the group is bored, frustrated, or just tired, consider breaking a little early. If all else fails, temporarily abandon the discussion guide. Return to any questions that did seem to interest the group, or turn the session into an open-ended brainstorm.

Probe for Different Perspectives

When someone says something that’s either unclear or contradicts an earlier statement, restate the idea or ask for clarification. Ask for examples of what the person means or definitions of terms he or she is using. Ask the group for agreement or dissent if someone introduces a new interpretation of the topic. Ask about different experiences or opinions.

Go with the Flow…Up to a Point

Group discussions have a tendency to spiral off on tangents, leaving your planned questions far behind. When they bring up important dimensions of a topic that you may have not yet considered, tangents can be very fruitful. But when the tangent moves on to points of marginal interest, end it quickly. Mention that people seem to be interested in a topic—no topic should ever be discouraged flat-out—then ask the group to end the discussion or to postpone it. As well, feel free to skip around your discussion guide if participants bring up a topic or question you had planned for later. Of course, if there are questions that absolutely have to be asked in a certain order, then (politely) insist upon it.

Help People Express Themselves

Give people time to think before you talk. Wait about five seconds after a participant finishes talking before asking a follow-up. Maybe someone else has something to add. When you ask a question, do the same thing before people answer. Doing it explicitly gives people permission to pause a bit before they talk: “Remember the last time you ordered spare parts? Think for a couple of seconds about what led up to that.” Five to 10 seconds is all that’s generally necessary. In the same way, remember to keep your body language nonjudgmental when people do talk. However, that doesn’t mean you need to act like a robot. Laughing along with a joke is also part of helping people feel comfortable. Be relaxed. Smile. Enjoy the opportunity to share in people’s lives. Have fun with it.

Watch videotapes of yourself moderating. Is your body language unconsciously expressing your personal preferences? Are you leaving room for people to think and talk?

Asking Questions

Asking questions is a subset of moderating, but there are enough elements that strictly relate to questions that we feel it deserves its own section. Several techniques help in asking questions and in clarifying the responses to questions.

Speak the Language of Your Participants

Avoid introducing new terminology and concepts to the group. New words and ideas tend to frame and bias discussion. If the group uses nonstandard words for a concept or creates its own definitions, let it. When you ask follow-up questions, use the participants’ own terminology and concepts, when possible. Don’t use industry jargon. Even if you think your questions are completely comprehensible, pretest to be sure. As a backup, have some examples ready to explain any potentially unfamiliar words or ideas. Try to elicit responses without the example first, so you don’t unnecessarily slant the discussion. But bring out the example if people seem confused. For instance, if the group doesn’t know where to start a feature brainstorm, give them an example of what is considered a new feature (e.g., “The car texts you a reminder when it needs an oil change.”).

But Ask Key Questions Verbatim

We know; we just told you to use the same terminology as the group. However, there’s an important exception. If you have a crucial idea to test, such as a value proposition or a design concept, present it identically to all groups. In order to reduce the ambiguity of the results, you need to make sure that all the groups are responding to the same stimuli.

Writing Before Talking

When people have written something down, they’re much less likely to change their minds and follow groupthink or a dominating personality during discussion. For example, participants who first rate a list of topics on paper have more individual and earnest responses in a subsequent group discussion of the ratings. For that reason, individual writing exercises can be especially useful in feature prioritization focus groups, where getting reliable rankings is the whole point of the session.

Prioritize Lists

If you have participants make a list—whether of concerns, needs, features, or what have you—always follow up by having them prioritize it. You don’t want to have to guess the most important item later. You can have them vote on the most important thing on the list (randomize when walking through the list!) or do a spontaneous finger tally for each item (everyone holds up a number of fingers to rate the item, the moderator quickly comes up with a rough average of the group’s ratings).

Chauncey Wilson, a senior user researcher at Autodesk, suggests the following technique for feature prioritization: give people a “menu” of features on a page with a description of each feature and “price” that’s based on an estimate of how much each feature costs to implement, in fictitious dollar amounts. For example, $100 for something that’s relatively straightforward and $500 for something that’s very involved. Then ask each person to “buy” up to $1000 dollars’ worth of features, writing their choices down on a piece of paper. After all participants have made their choices, discuss why people made certain choices.

Handling Focus Group Problems

Misleading Results

The most common problem in focus groups is misleading or inaccurate results. People are conditioned (or predisposed, depending on whose theories you follow) to avoid conflict in small groups. People have a tendency to go along with what they think other people in the group want, even if they don’t really agree. This is called groupthink, and it presents the illusion of consensus where none actually exists. Failing to question this apparent consensus leads to dangerously unreliable results. To minimize groupthink, first make it clear to the participants that you encourage sincere, polite disagreement. Then include individual writing or sketching exercises as a first introduction to a new topic on which no consensus has yet developed. Careful recruitment will minimize other groupthink problems. Cultural patterns of respect for people of certain ages, genders, income levels, and professions can all lead to some individuals determining a group consensus, often without conscious intent.

Sometimes, however, the problem lies with the team. Focus groups also produce misleading results when the discussion guide incorporates fundamental misunderstandings about people’s experience. Hopefully, you will pay attention to any obvious warning signals—perhaps an overly quiet group, or a few people who insist on talking about what matters to them, rather than your questions. Then you can adjust your approach. The worst outcome is a group that meekly follows your lead, and hence never mentions a critical aspect of their experience. The best way to avoid this is by interviewing a representative of the target audience beforehand. If you discover a misunderstanding after the focus group series has begun, rewrite the guide as soon as possible. If necessary, schedule more groups to be sure you’ve asked enough people the right questions.

Rough Emotions

The unpredictable mix of personalities in focus groups can create uncomfortable situations. After pretesting your discussion guide, you can probably anticipate which topics might be emotionally difficult. The best way of dealing with powerful feelings is by focusing on the ideas behind them, as long as emotional release doesn’t dominate the entire session. If you expect strong feelings, block out some time for participants to discuss their emotional reactions. If a topic unexpectedly stirs up emotional reactions, it’s respectful to let participants discuss them, even if it means skipping a couple of questions in the guide. However, the moderator should tactfully move the discussion as soon as possible to a more distanced analysis of any experiential factors contributing to the emotions.

Defuse hostility toward other participants, however, as soon as possible. When a participant says something that other participants find offensive, sometimes a fruitful discussion ensues. But sometimes the group shatters into hostile partisan groups or unites in attacking the offender. Both are extraordinarily damaging to your plans for the group, not to mention upsetting for everyone. To head off attacks, first ask if anyone else shares that view. Then ask if anyone has a different view. Use follow-up questions to get at the rationales underlying the controversial opinions. Ask angry participants why they disagree with the statement. Stay as neutral as you can, even if you yourself are personally offended.

Dismissing Participants

On rare occasions, you will need to eject someone from the group. Whether innocently or not, occasionally a participant will mislead the recruiters and fit the audience profile so poorly that it’s disrupting conversation. For example, you might have scheduled a focus group with first-time brides-to-be on wedding planning services… only to find that one participant actually has a lot of experience helping friends and family plan their ceremonies. You had screened out professional wedding planners as well as people who had been married before, but you hadn’t anticipated this special case. So instead of answering questions from their own perspectives, participants keep asking her for advice and deferring to her expert knowledge. It’s not her fault, but it’s destroying the utility of the group. More unpleasantly, every once in a blue moon you can get a participant whose hostility or bullying is making it impossible for other people to speak their minds. Whether the person is pleasant or obnoxious, always be polite when you request that he or she leave.

Dismissing participants is a last-ditch solution. Do it only when both the moderator and the assistant agree that it’s necessary for the focus group’s effectiveness.

The assistant moderator should do the dirty work of asking the person to leave. To manage it discreetly, the assistant moderator asks the participant to leave during a scheduled break in the group. As the group is completing a demographic form or a nondisclosure agreement you can duck out and discuss any potential problem with the assistant moderator. In the middle, unfortunately, you may just need to pass notes. Later on, the moderator will announce a “five-minute stretch” or a similar pretext for breaking the action. As it starts, the assistant moderator should come into the room and politely ask the person to go with him or her. The assistant thanks the person for participating, hands over the promised honorarium, and says good-bye. Everyone will know what happened, but the excitement of seeing someone “get kicked out” will quickly fade. If people ask you questions, simply tell them that you felt that the person wasn’t a good fit for the group. Don’t commiserate or apologize.

Don’t let in latecomers who arrive after the introductions. Give them their full honorarium and say good-bye. Bringing new people up to speed is disruptive, and the presence of a “stranger” puts people back on guard after all the icebreaking you did earlier.

Managing Observers

As many people from the development team should attend as many focus groups in a series as possible. This gives the team instant information about their ideas, and it provides the analyst access to valuable technical expertise. For the same reasons that there should be more than one group per topic, people should be encouraged to observe at least two groups if they’re planning to observe any. It’s much easier to know which phenomena are unique to a given group of people and which may be more general phenomena when you’ve seen several groups discussing a given topic.

Observers can communicate with the focus group moderator through notes, chat, or text messages. If you are using paper notes, collect questions during stretch breaks to minimize any disruption to the group. Using text or chat to ask questions is potentially less disruptive, but requires constant monitoring by the moderator and assistant. If you are using text or chat, use an account or number that does not get a lot of traffic. You don’t want to be fielding messages from your friends and family when your attention should be on the focus group.

Focus Group Observer Instructions

Since observers are an active part of the analysis process, it’s important that they know how to approach the observation process. There’s a right way to observe a focus group and many wrong ways. Make a point of meeting with new observers beforehand and prepare them for observing the focus group. The following instructions help prepare observers and can be presented as part of the initial orientation or as a written list.

• Listen. As tempting as it is to immediately discuss what you’re observing, make sure to listen to what people are really saying. Feel free to comment, but don’t forget to listen.

• Don’t write people off. Sometimes, a participant may say things that indicate that he or she isn’t getting it. Never assume that someone has nothing important to say just because they aren’t interesting or insightful from the start. Understanding why one participant “doesn’t get it” can hold the key to understanding the perspectives of everyone who “does.”

• People are contradictory. Listen to how people are thinking about the topics and what criteria they use to come to conclusions, not necessarily the specific desires they voice. A person may not realize that two desires are impossible to have simultaneously, or he or she may not care. Two people may think they’re agreeing, when they’re actually saying the exact opposite.

• For that reason, don’t take requests too literally. Use people’s statements as guides to how they think about the topic and what they value, but don’t treat the specifics of their statements as gospel. If everyone in a group says they like or hate something, that doesn’t mean that the whole world thinks that way. It is, however, a good indicator that you should be paying attention.

• Focus groups are not statistically representative. If four out of five people say something, that doesn’t mean that 80% of the population feels that way. It means that a number of people may feel that way, but it doesn’t mean anything in terms of the proportions found in the population as a whole. Nothing. Zilch.

• Focus group participants are experts. The participants in a focus group know what they want to do and how they currently do it. Listen to their needs and their experiences. Treat them as consultants who are telling you what your customers need, not as novices who need to be educated or the targets of a sales pitch.

• Focus groups are not a magic bullet. A couple of good ideas from every group is enough to make that group worthwhile, but not every statement that the group participants make should be followed to the letter.

• Feel free to pass questions to the moderator, but don’t overdo it. Occasional questions to the group are okay, but there should not be more than a couple in a session. Write your question clearly and concisely, and phrase it as if you were talking to the moderator. When appropriate for the flow of conversation, the moderator will introduce the question. However, the moderator may decide to never introduce your question if the timing or topic is inappropriate.

Hiring Experts

At this point, you’ve likely concluded that focus groups are not as simple as they seem. Effective focus group moderation is particularly difficult. It’s significantly more complicated than a one-on-one interview. You can hire a company that specializes in focus groups rather than expending the time and energy to do the process in-house. There are several things to consider when hiring a company to run your focus group.

Does the moderator know the subject? A moderator needs to be able to think on his or her feet about the subject and probe appropriately. The company should have some experience with the subject. If the moderator does not, then you should prepare to brief him or her in depth on the subject, the terminology, and the associated issues.

Can the company recruit the right people? Getting the right people for the focus group is critical to that group’s success, thus the recruitment method is important. Ask the company how they get their database and how they will screen people for your focus group. Make sure to review the screener, or write your own screener for them. Information on writing screeners is in Chapter 6.

How long is the turnaround time? The analysis method varies from company to company. Depending on the final deliverable, it can take from days to weeks. Make sure to find out what they are planning to do and how long it will take. You may want to forgo a fancy report and slide presentation for a list of findings and a discussion with the moderator and analyst.

As with any contract work, ask for references to the last couple of projects that the company has completed and follow up on them. Do not be shy about asking for satisfaction. If anything is amiss—the recruiting, the moderating, the analysis—call them on it. If necessary, request that additional groups be run at their cost.