Chapter 6

Universal Tools

Recruiting and Interviewing

No matter what the research, there are two things you’re always going to be doing: looking for people who will give you the best feedback and asking them questions. These two elements, recruiting and interviewing, make up the backbone of every successful research project, and although some of this information is covered in other chapters, they deserve a chapter of their own.

Recruiting

Even if everything else is perfect, if you get the wrong people to talk about your product, your research can be worse than useless since it gives you confidence in results that don’t represent the views and behaviors of your real users. Every product has a target audience, from toasters to missile guidance systems. You need to understand the experience of the people who are actually going to want to use, understand, and buy your product. Anyone else’s experience will be of marginal use, or even deceptive. So if you’re making a missile guidance system and you invite the North American Toaster Enthusiasts to speculate on how it should be improved, you’re not going to get useful Army-related feedback. (And if you decide to take their speculating seriously, you may end up with a missile that has a 30-second pop-up timer.)

The process of finding, inviting, and scheduling the right people for your research is called recruiting, and it consists of three basic steps: determining the target audience, finding representative members of that audience, and convincing them to participate in your research.

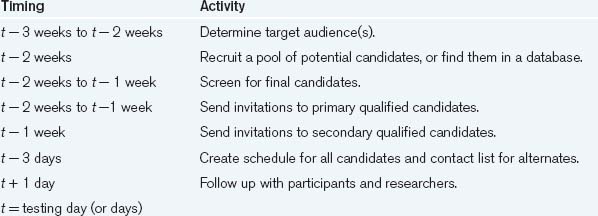

The time required for recruiting can vary widely, depending on how accessible your target audience is and the location and duration of the research you have planned. For example, imagine a study in which you want to observe style-conscious young adults shopping for their favorite hair products in the stores they usually visit. You will be spending a fair amount of time with each participant (not to mention traveling to the stores) and you may need to pay them a lot for their time. To make this research valuable, you need to be choosy and screen each candidate individually before selecting them for the study. Table 6.1 shows the recruiting schedule you might follow.

Table 6.1. Typical Recruiting Schedule for a “Shop-Along” Field Study

Overall, this process could take two hours for each participant—more if you’ve never recruited that kind of participant before.

Now, imagine a very different study: you want to learn whether adding photos to your online hair care shopping guide helps users decide which products to buy. If you conduct the study online and have users participate remotely from their homes or workplaces, you may be able to recruit people and run the sessions inside of a day (see Table 6.2).

Table 6.2. Typical Recruiting Schedule for a Remote Web Usability Study

If you frequently need to conduct in-person studies, it is useful to have someone recruiting full time, rather than trying to do it in between other work. Recruiting can be almost a full-time job in itself, and it always turns out to be more work than anticipated. To reduce costs, a temp or an intern can recruit full time if given some training.

Pick Your Audience

As a general rule, the longer your company has been providing a product or service, the better you will know its audience. If they have been selling laser printers for years, they should have detailed information about the people who buy them, which you can use in recruiting. On the other hand, if your company has just invented a new way to print photographic images on cupcakes, you may not have much to go on. If you are doing early-stage research to discover business opportunities, part of your job may be learning who the users could be. In that case, you should begin by finding out how your team currently defines its audience and recruit those people for an initial round of research to confirm your assumptions. If those participants turn out not to be interested in your product, you may need to recruit different people for another round, so plan accordingly.

As a researcher, it’s important to question assumptions about audiences. For example, companies accustomed to traditional market research often want to have purchasers or final decision makers, such as chief executives, as usability participants. But the reality is that executives likely don’t spend much time using your product—their employees do. If you recruit executives based on a client request and despite evidence that executives are not your product’s main users, you risk designing for an audience that’s not actually there.

This happens all the time and is a great source of pain for the people who actually have to use business software. In that sort of situation, you may need to argue for two studies—a usability test with frequent users and surveys or interviews with decision makers about purchasing behaviors.

So how do you define that group of “right people”? For most user research, the most important recruiting criteria are behavioral. That is, you are looking for people who actually do (or want to do) the things that your product or service supports. If your product is a new bicycle helmet with a fold-out rearview mirror, your research audience might be people who ride bikes regularly and use bike safety accessories. They might also be people who don’t ride regularly but would if they felt safer on the road. For some products, it may be especially important to know how intensively they use (or don’t use) various computing and communications technologies, such as online games, mobile devices, or digital video. In that case, break that information out into a technological profile.

What about demographics? Shouldn’t things like age, gender, geographic location, and household income be used to pick your participants? For a relatively new product or service with not many users yet, this can unnecessarily make your recruiting job harder. For an established product with many users, it can be important for your participants to resemble your existing users demographically. For example, say your company produces online bridge tournaments and the vast majority of your players are over 60. For your user research, you need to get people who play bridge and have played online, or you are unlikely to learn anything useful. Even if you do that, though, you are likely to miss some important findings if your participants are all under 40. (Plus, it will be hard to convince your stakeholders that your research is valid.) If your recruiting efforts consistently yield participants who don’t resemble your users demographically, it’s a sign that you need to find new channels for recruiting. In general, recruit based on behavioral criteria first, and if there are demographic attributes that are true of most of your target users, make sure at least some of your participants have them, too.

Put your profiles of the product’s target audience into writing, if they aren’t already written down. If you’re making a website that helps people plan a night out, your primary audience may be single professionals who go on lots of dates and use the web on mobile phones as well as PCs.

Initial Date Planning Profile

Demographics

Ages: 25–55

Gender: male or female

Single

College educated

Income: $60K+

Behaviors

Go out on a date at least once a month

Technology Use and Experience

Use the web at least one hour per day

Access the web from a mobile device at least four times per week

Have gone online to get information about local restaurants, entertainment, or events in the past year

Now, ask yourself what makes the ideal research participants different from the target audience as a whole. What kind of people will give the best feedback for the specific research you are doing? Ask yourself:

• Which segments of your audience do you need to focus on? For example, the people planning dates, or the ones who get invited out?

• How much experience should they have with your product? If you’re testing a new interface, do you want people who are used to the old version, or others who can see it “fresh”?

• How much experience should they have with competing products?

• Are you targeting a single group of users or multiple groups? For example, city-dwellers and suburbanites might be different enough that you should treat them as two groups.

• What are undesirable characteristics that should be avoided? In this example, people who consider themselves experts on their cities might not give useful feedback.

Explore the answers to these questions and modify your profile accordingly. Remove factors that are not going to affect how people use or view the product and add information. Focus on isolating the factors that will make them an ideal research audience.

Revised Date Planning Research Profile

Demographics

Ages: 25–55

Gender: male or female

Single

College educated

Income: $60K+

Behaviors

Invite someone out on a date at least once a month

Choose places and activities for dates

Consult friends and local media sources for ideas when planning dates

Technology Use and Experience

Use the web at least one hour per day

Access the web from a mobile device at least four times per week

Have gone online to get information about local restaurants, entertainment, or events in the past year

Be careful not to overdetermine your target audiences. If you find yourself trying to define multiple conditions to the point where you’re not sure you can find people who meet them, or if some of the restrictions are mutually exclusive, consider breaking the research into several groups. Thus, if you’re making a mobile application for truck drivers and you need the perspectives of both long-haul and short-haul drivers, rather than mixing the two groups into one piece of research or finding drivers with experience in both fields, consider running the same research with two groups.

Not all research should be done with “average” users. If you are looking for new ideas to improve or differentiate your product, consider talking to some people who use it intensively, have an unusual way of using it, or have special needs. You may even want to interview people who have chosen not to use it.

Find Your Audience

Once you have the research profile, you need to go out and look for those people. You have two groups to draw upon: people already in contact with your company and everyone else. Recruiting from the first group will always be the fastest and cheapest option. But what if this group is small, or doesn’t include enough of the right people for your research? If you have plenty of time, you can do some outreach to find the participants yourself. If not, you can use a commercial recruiting service. This may be an agency that recruits the people you need, a software tool that puts you in touch with them online, or a combination of both.

Recruiting on Your Own from Existing Contacts

Existing contacts can include current customers; people who have created accounts on your website; people who have signed up for your newsletter or given you their business cards at trade shows or events; your company’s friends/fans/followers on Facebook, Twitter, or other social networking services; your employees’ own families and friends; and even brand-new employees.

Many of the channels you already use to interact with customers can also be used to recruit research participants. For example, you could post a call for participants on your company website (Figure 6.1), email newsletter, or Facebook fan page, or tweet it out on your Twitter account. Obviously, make sure to choose the channels where the people who fit your research profile can be found. If you’re looking for expert users, don’t announce it in the new user help forum.

Figure 6.1 A call for research participants on Intuit’s website (http://about.intuit.com/research/). The site explains why Intuit does research, how users can participate, and the incentives offered.

For some research needs, you may have a very specific set of current users you want to contact; for example, customers who recently upgraded from the free version of your service to the pay version. In these cases you may want to email users and invite them to participate in your research. The advantage of this method is that you may already have information that you can use to prefilter the people you ask. For example, if you want to learn about new users’ experiences, you can invite only people who have signed up for your service in the past month. On the downside, some users may find it intrusive or annoying to be contacted in this way. To avoid alienating invitees, state the purpose of your contact in the subject line of your message, offer them an incentive for participating, and give them a way to opt out of being contacted for research in the future.

Recruiting on Your Own from a Wider Population

Maybe you don’t yet have a product, or even a web presence. Perhaps you are a new company or are trying to enter a new market where you don’t have many contacts yet. If you’ve done the work to define your audience precisely, it should not be too hard to find other ways to reach out to them. But it does take some effort! This is why people hire commercial recruiting companies—locating people on your own often costs less, but it can require some creativity and extra effort.

Say you want to do research with urban dog owners. You could post messages in online discussion forums for dog owners, buy ads on pet care websites, or post flyers in pet supply stores, vets’ offices, and city dog parks. In other cases, it may be better to do your outreach more personally. If you are looking for parents of children with learning disabilities, you probably need to get to know a few of those people and earn their trust. Once they understand your objective, they may be able to introduce you to others.

Many of the techniques we introduce here can push the boundaries of the recruiting schedule in Table 6.1. If you try one on a short schedule and aren’t having immediate luck finding people, be prepared to try another—fast.

• Community email mailing lists and online forums. Some communities have their own email mailing lists. Whether it’s people who live in a certain area or people who use a certain product or people who are in the same industry, there are a lot of mailing lists in the world. After you’ve identified a list or forum, check how busy it is. Low-traffic sites might not have the membership numbers or interest to reward your effort in making contact. Once you’ve chosen a list, make sure that you know the community’s rules and you have the organizers’ permission before sending mail. It may help to start a conversation with the organizer first, then have the organizer send the message on your behalf. That way, community members can have more confidence that your request is legitimate. Never spam (send unsolicited email). Personalize the invitation to the group, making it clear why you’re sending the message and what the benefits of participation are.

It’s important to give people a reason to participate in your research, but that reason doesn’t have to involve money. If you believe that your project has the potential to improve the lives of dogs and dog owners, or help dyslexic kids in school, say so. Overemphasizing financial benefits—especially if you have a very low project budget—can actually turn people away.

• Neighbors. Your corporate neighbors are a great research resource. They may be familiar with your company, and it’s easy for them to come into your offices during a lunch break. Send a note to your neighbors’ office managers and ask them to post an invitation in a public place.

• “Friends and family.” We put this in quotation marks because it’s such an old standby. You don’t want to pack a study with your friends and family—their relationship to you will slant how they behave. But recruiting people you don’t know as well—say, friends of friends, or family members of friends—is perfectly legitimate. Friends can be especially helpful with niche recruiting requirements. If you’re looking for martial arts experts, why not ask an acquaintance who teaches taekwondo? Send an email about the project to people you believe will have friends and family who fit the recruiting criteria. Ask them to forward it on. Keep the email short and to the point, or people won’t forward it. The one big drawback to this method is that your friends probably resemble you in important ways. They’re your friends, after all! So if you rely on their friends, you may well bias your results toward people who also resemble you. So be careful—but do call on your friends in a pinch.

• Ads. Online ads are easy, are often inexpensive, and hold the promise of reaching a vast number of people very quickly. You can take out ads on your site and on other sites (in 2012, Facebook is a common choice). However, we have had mixed results using online advertising to recruit participants. Our experience has been that ad recruitment is more successful when you are recruiting based on a hobby or deep personal interest. That is, an ad for martial arts experts will likely be more successful than one for people who go to the gym occasionally. However, that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t give ads a try. Make sure that the ads specify the location of your study and any incentives. And do make them attractive (as ads, they need to compete with all the other ads). An animated banner can, for example, read “Bay Area Black Belt? Want $60? Click here!” Clicking on the ad then leads people to your project website, screening survey or contact form.

• Traditional methods. When you need people who can come into your office, consider traditional advertising methods. Classified ads online or in local newspapers can work, though an ad in the help wanted section might get confused for a job offer. If you’re in an urban area, there may be leaflet distribution services that can put your invitation on every corkboard in town (college campuses are an especially good source of such bulletin boards and are a great way to recruit college students if they’re part of your audience).

If you’re at a loss for how to target a certain group of people, first find one person who matches your research participant profile. Then sit down with him or her and brainstorm about other ways that similar people can be reached. Talk about places he or she goes—online and offline—and habits and interests. Suggest some of the methods in the preceding list and ask how to tailor them specifically to his or her lifestyle.

Using a Commercial Recruiting Service

Commercial recruiters have databases with thousands of people from all walks of life. For them, the task of finding people is fairly straightforward: they search through their databases for basic demographic matches, and then they screen those people for the criteria that you’ve determined. We describe how to work with commercial recruiters later in the chapter.

The decision about whether to work with a commercial recruiting firm or do it yourself largely depends on available resources. Recruiting is a time-consuming process, especially for relatively rare groups or for people with complex schedules. However, basic recruiting can be a fairly straightforward process if organized well and given sufficient time.

Keeping Track of People Available for Recruiting

However you connect with potential research participants, you should keep a database of people who are willing to have you contact them directly for user research. Be sure to record how you got in touch with each person. You should also keep a list of people who have asked not to be contacted, so you can make sure not to bother them. Ideally, this should be integrated with whatever customer contact management system you use.

You should try to have at least ten times as many people in your contact list as you expect to invite to your next round of research.

Additional Recruiting Tips

Rather than including lengthy explanations in email, you can make a web page that explains the research program and then send email that points people to it. This can be the same page that collects their demo or web info, but it can be a purely informative page, too. The page should explain the purpose of the recruiting, the incentive, the occasional nature of the research (so people don’t think it’s a job), and how they can get more information. Add frequently asked questions to it as the recruiting process matures.

Clearly state the location of the research and the geographic area from which you’d like to recruit in all invitations. You can’t predict who will read a request, and it’s little use to have people offer to participate from halfway around the world (or even 100 miles away) unless you’re willing to pay them for their transportation costs or you’re doing research remotely.

Keep track of when and how people found out about your program. This will tell you which techniques work best and, moreover, how your recruiting methods may affect the perceptions of the participants. People who have purchased something from your company will know more about your product and have stronger opinions than people recruited through your neighbors, who will in turn have stronger opinions than people who saw an ad.

Don’t get to the point where everyone you’re recruiting has identical qualities or has been recruited in the same way. Every attribute in a profile has a range of values that could satisfy it, and recruiting should strive to get a diverse group of people within the range. For example, when participant ages are defined to be between 25 and 35, it would be better if the recruits ages encompassed the whole range rather than all being 35.

Try to keep the number of repeat recruits down. In most cases, it’s generally acceptable to recruit someone who hasn’t participated in any kind of usability or marketing research in six months. In some cases, however, this requirement will have to be waived—for example, when time is short or the person has a rare profile or he or she is in a popular market that gets recruited a lot (IT managers are few, and are the targets of much market research, for example).

When someone gives you especially good feedback, make sure to note it in the database (you can have a check box for “great response”). If you ever need a couple of people on short notice, you can just pull people who you know are articulate and insightful.

If time allows, run a small recruiting test. Recruit one or two people and run them through the research. If they provide good feedback and they’re in the right audience, proceed with recruiting everyone else the same way.

The Screener

Your next task is to create an appropriate script for the recruiter to filter the general population for the criteria specific to your research. This is called a screener.

The screener is probably the most important part of the recruiting process. It’s a script that filters out the people who will give you good responses from the ones who merely match your basic criteria. The screener can be a form posted on the web, a script read by the recruiter over the phone, or a questionnaire sent in an email. If you are doing an unmoderated study, such as an online survey, you can have people complete the screener at the beginning, with only screened participants proceeding to the actual research.

Getting the screener right can get you people who are likely to be interested in the product and can speak about their experiences intelligently and eloquently. Getting the screener wrong means getting people who are, at best, only marginally interested in what you have to offer and, at worst, uninterested and inarticulate.

Screeners vary from project to project and from recruiter to recruiter, but there are some general rules that apply to most.

• Stick to 20 questions. There’s a reason that game exists. It’s possible to find out almost anything about someone in 20 questions. Most target audiences can be defined in 10 to 15 questions, and if the people are prescreened through your database, you can get away with fewer than five.

• Make it short. It should be possible to get through a whole phone screener in five to 10 minutes.

• Be clear and specific. The person responding to the question should know exactly what kinds of answers are expected.

• Never use jargon. Use simple, straightforward, unambiguous language.

• Ask for exact dates, quantities, and times. This eliminates the problem of one person’s “occasionally” being another’s “all the time.”

• Every question should have a purpose. Each question should help determine whether this person is in the audience or not. Don’t ask questions that are incidental or “nice to know,” since answers to them will not be useful in recruiting and take everyone’s time. Save “nice to know” questions for when you actually meet a participant.

• Start with the questions that will screen people out. The earlier a question is in the screener, the more people it should eliminate from the pool of potential participants. This saves both the recruiter and the participant time since earlier questions weed out later questions that would be irrelevant otherwise. For example, if you know you only want people over 60, but you want a variety of experienced and inexperienced Internet users, put the age question before the Internet experience question.

• Questions should not lead. There should be no value judgments or answers implicit in the questions. “Are you bothered by the excessive lag times on the web?” implies that the person perceives lag times and that he or she should be bothered by them. Instead, phrase questions in a more general (but not more ambiguous) way, and then look for specific responses. “Are there things on the web that regularly bother you? If so, what?” could get at the same kinds of issues as the first question, without its bias.

• Clearly state the format of the research. State what the research is for, when it’s going to happen, how long it’s going to take, how much the incentive is, and whether the participants should do anything ahead of time (and whether they should do nothing ahead of time).

• Build in flexibility. Let the recruiter know the acceptable parameters for answering each question, so that you don’t needlessly dismiss people who can provide valuable feedback.

• Prioritize helpful participants. There is nothing more frustrating than an interview with someone who hates talking or a usability test with someone who won’t follow directions. Including open-ended questions can help the recruiter guess whether a person will be responsive and articulate.

Sample Phone Screener

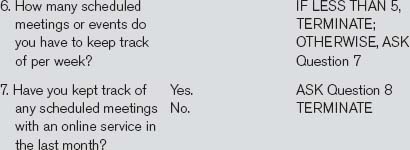

This is a telephone screener for a site that offers an online calendar. The target audience is mostly existing users, but the screener has been expanded to include a couple of potential users and a power user (to get a taste for several different kinds of user experiences).

This screener consists of three sections: an introduction for the recruiter that specifies the ideal target audience, an introduction for the participants, and the main set of questions and selection criteria. It is a relatively complex screener that would probably be too involved for a first usability test.

Target Audience

6–9 people total: 4–6 current users, 1 power user, 1–2 nonusers (but likely potential users)

Note that some of the criteria are specific, such as the frequency of Internet access and the number of events entered into the calendar, whereas others (such as the gender and age) have ranges.

Current User Screener

Hello, my name is [screener facilitator name here] from [your company name here]. We are seeking a few people who are interested in participating in a paid evaluation of a product that you may find useful. This is not a sales call, and no sales or solicitation efforts will be made at any time.

The evaluation will consist of a one-on-one interview on January 20 or 21 in downtown San Francisco. It will be during working hours and will last about one hour. If you participate, you will receive a cash stipend of $100. The interview will be strictly for research, and all of your comments will be confidential. If you are interested in participating, I need to ask you a few questions to see if you’ve had the kind of experiences we’re looking for.

The introduction simultaneously sets people’s expectations and serves as the first round of questioning since people will immediately say if they’re unavailable on the given date or if they’re unwilling to participate. It’s also careful to describe the general nature of the research without going into specifics that may skew people’s responses.

Alternatively, you can use a more generic introduction (“We are conducting a study, and I would like to ask you a few questions”), but you run the risk of going through the whole process just to find that the person is not available on a given day or is uninterested in participating in this type of research.

Eliminate people who work in industries that can present a conflict of interest. People who are in advertising, usability, user interface design, and market research should almost always be eliminated since they’re too aware of the kinds of issues that research is aiming to uncover and are unlikely to give an unbiased perspective (even if they want to).

“Terminate” is an instruction to the recruiter that tells him or her to stop the recruiting process and wrap up the interview. There is some termination text provided at the end of the screener.

Although many of these questions will have already been filtered for if these names were pulled out of a database, it’s still useful to make sure that the information is accurate, so it’s a good idea to verify the information again. Additionally, the age and income questions may be considered to be invasive by some people. In many cases, that information doesn’t affect people’s behavior and the questions can be eliminated; in cases where the information is of secondary importance, it’s possible to move the questions to the end.

When people have participated in user research recently, they’re more likely to give unconsciously biased responses since they’ll be familiar with the format of the research and may try to anticipate the “appropriate” answers. Since you’re almost always looking for unguarded, unbiased responses, it’s generally a good idea to eliminate these people from the research unless you have no other choice. Moreover, some people see the incentive payments as a good way to supplement their income and may try to get into any kind of marketing or usability research project. Inviting such people should be avoided entirely since they’re unlikely to provide natural or truthful responses.

When you are short on time or when you can interview only a couple of people, it’s sometimes useful to filter for people you’ve interviewed before rather than filtering them out. People who are known to give good, honest, articulate feedback provide a shortcut to useful information. In such situations, it’s important to inform the analyst about the participant’s background since it’ll probably affect the way he or she interprets the results.

| 15. In a couple of sentences, list your favorite websites lately and describe why you like them. | [NOTE DOWN] TERMINATE IF INARTICULATE; OTHERWISE, SCHEDULE |

Open-ended questions like this serve two purposes. They give the recruiter an idea of how articulate a potential participant is, and they can collect information that’s not easily formatted as a multiple-choice question. Save them for the end, and don’t put more than one in any given screener since they’re time-consuming and don’t filter many people out. (That said, some recruiters prefer to ask the open-ended question at the beginning since it’s less intimidating and can catch terminally inarticulate participants early in the process.)

| TERMINATE | That’s all the questions I have. Thank you very much for participating. Although we’re not scheduling people who fit your profile right now, we may call you again for a different research project. |

If you’re using the more generic introduction, you can also replace the termination statement with something less specific, such as “That’s all the questions I have. Thank you very much for participating in our study.”

That’s it for the questions. Would you be willing to come into our downtown San Francisco offices for a one-hour paid interview on January 20 or 21? You will be reimbursed $100 for your time, and your help will be greatly appreciated by a development team that’s currently making a product you may be interested in.

Online Screeners

Online screeners are similar to telephone screeners in terms of the kinds of questions that are asked, except that online screeners are designed to be answered directly by the participant. This makes them similar to a survey questionnaire in format. In fact, you can use the same writing style and online tools to create them that you would use to run a survey. See Chapter 12 for how to write survey questions and select an online survey tool.

Ideally, you should use a tool that lets you create screeners with branching logic, so that you can terminate people right away if their answers disqualify them, just as you would with a phone screener. Include a question at the beginning to determine whether they are available at the times and locations of the study and a form at the end for qualified respondents to provide their contact information.

Once your screener is online, you need to invite potential participants to fill it out; email is generally the easiest way of doing this. Your first task is to convince recipients not to ignore the invitation, so if you are paying an incentive, make that clear in the subject line. However, don’t put the subject in all caps or use exclamation points, or your invitation will look like spam. Make it clear to readers why you are contacting them, describe the incentive they can earn if they qualify, and state how long the screener will take to complete. Since they haven’t qualified yet, there is no need to describe the research in detail.

SUBJECT: Earn $100 helping us make a better online calendar

BODY:

eCalendar is looking for a few people to help us evaluate a new online scheduling product. Participants will receive a $100 gift card for completing a one-hour interview on January 20 or 21 in downtown San Francisco.

If you are interested, please go this web address to complete a five-minute questionnaire:

http://www.ourcompany.com/research/screener

If you qualify for the study, we will contact you to schedule your session.

You have received this e-mail because you are a current or former eCalendar user. If you would prefer not to be contacted about research studies, please let us know and we will remove your address from the list.

Scheduling

Scheduling procedures largely depend on how you will be conducting the research. Sessions conducted face to face should be scheduled at least a week in advance, longer for business users, if significant travel is required, or if multiple users will participate together. Remote sessions conducted by phone or videoconference can be planned on less notice than in-person research. In fact, some remote research platforms allow website users to be recruited “live”—while they are using the website—then get screened quickly and do the research session right away. Unmoderated research happens at the convenience of the users; you just have to give participants a deadline and remind them as needed.

Whatever the parameters, you should begin by defining a scheduling window in which the study will take place. What are the appropriate times for the researchers? Are there times that are inappropriate for your target audience? (Physicians and network administrators, for example, are almost impossible to schedule during weekday working hours.) Are there key observers who need to be there at certain times? Company meetings? Holidays?

Now, if your research is appointment-based, start scheduling. There are lots of ways to schedule people, and you should feel free to use whatever procedure is right for you. The following sequence was used successfully at Wired Digital and is similar to the procedures used by other recruiters:

3. Receive responses and schedule primary candidates.

4. Invite secondary candidates.

5. Receive responses and schedule secondary candidates.

6. Confirm primary candidates.

7. Confirm secondary candidates.

8. Send thank-you notes to unscheduled candidates.

9. Make email or telephone confirmation calls to all participants the day before their scheduled time.

10. Create and distribute a schedule of all participants.

11. Direct participants and/or researchers to the location where the study will be held.

For events with fixed schedules, such as focus groups or when critical observers have limited schedules, invitations are straightforward.

For more flexible situations, schedules should be constructed around the participant’s preferences. It’s often as effective to ask candidates for a list of times when they’re available as it is to dictate times when they should show up. Allowing participants to drive the scheduling also shows them, upfront, that their input is valuable.

The Invitation

The invitation should reiterate what the research is about, why participation is important, how much the participant will be paid, where the research will take place, and when they should show up (or, in case of site visits, when they can expect the visitors to arrive). Here’s an example of an invitation email:

Thanks for your interest in eCalendar research. You are invited to participate in our next user study. One-hour sessions will be held on WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 8 and THURSDAY, DECEMBER 9 at our offices on 123 Main Street in downtown San Francisco. An honorarium of $100.00 will be paid to you following the test session, and you will be required to sign a nondisclosure agreement prior to beginning the study.

If you would like to participate, you MUST RESPOND TO THIS MESSAGE BY THIS THURSDAY, DECEMBER 2. Please answer the following:

When are you available to attend a test session? Please indicate ALL the times you could attend:

[ ] Wed, Dec. 8, 11:00 AM–12:00 PM

[ ] Wed, Dec. 8, 12:30 PM–1:30 PM

[ ] Wed, Dec. 8, 2:00 PM–3:00 PM

[ ] Wed, Dec. 8, 3:30 PM–4:30 PM

[ ] Wed, Dec. 8, 5:00 PM–6:00 PM

[ ] Thur, Dec. 9, 11:00 AM–12:00 PM

[ ] Thur, Dec. 9, 12:30 PM–1:30 PM

[ ] Thur, Dec. 9, 2:00 PM–3:00 PM

[ ] Thur, Dec. 9, 3:30 PM–4:30 PM

[ ] Thur, Dec. 9, 5:00 PM–6:00 PM

We’ll get back to you on Friday, December 3 with the date and time of your session.

Confirmation and Reconfirmation

Since a lot of dates and times fly around during the scheduling process, it’s a good idea to confirm the final date and time. Send a short, clear email or other message, like this:

Dear [name here],

Thank you for responding to our invitation to next week’s usability study. We’re confirming that your appointment is for:

Day: Monday, December 8, 2012

Time: 5:00 PM

VERY IMPORTANT—YOU MUST CONFIRM YOUR APPOINTMENT

In order to confirm this appointment time, please either REPLY TO THIS EMAIL or CALL 415-235-3468! If you don’t respond, we will assume you are not coming, and we’ll have to schedule another participant in your time slot.

All confirmations should also contain a line to the effect of “Because we have tight schedules, it’s critical that you show up exactly at the time you’re scheduled or a few minutes early,” as well as specific transportation and parking instructions.

OUR ADDRESS

We’re located at 582 Market Street at Montgomery, Suite 602, in the Hobart Building. There is a BART and Muni station right in front of the building, and all the trains stop there. The numbers 2, 7, 9, and 14 buses travel at street level. If you’re driving, the closest parking is an underground pay lot at Mission and Second that is best approached from Mission Street going east.

OTHER GOOD STUFF TO KNOW. This session should last about one hour, and you’ll receive an honorarium in the amount of $100.00 by check within two weeks following your participation. The schedule we have set up for this test is very tight, so if you think you’re going to be running late, PLEASE CALL (415) 235-3468 TO INFORM US. If at all possible, plan to arrive 10 minutes before your scheduled appointment time, and you’ll really be a star!

Thanks again and we’ll see you next week!

In addition, we found it helpful to standardize the format of all correspondence with a one- to two-sentence summary of the message at the beginning; a standard layout for all messages; and a contact person’s name, email address, and phone number at the end. Encourage the participants to contact that person as soon as they know they won’t be able to make an appointment or if they have any questions. Keeping the text tight, but with humor and personality, helps make the process feel less clinical, and people are more likely to read it.

Finally, the single most effective way of preventing no-shows is a combination email and telephone reminder the day before the scheduled appointment. It reminds people, subtly reinforces the importance of their input, and gives you time to schedule an alternate in case they can’t make it.

Choosing an Incentive

An incentive is something that encourages and rewards people for their help. As such, it needs to convince people that they should share their time and experience, and it needs to communicate their value to your company. Never shortchange people.

Although the chance to influence a favorite product can motivate people (and thus should always be emphasized), for most people the best incentive is cash. For increased security, widely accepted gift cards work, too. A starting point for incentives in major metro areas in 2012 is $1.50 for every minute of in-person consumer research and $2 per minute for business-to-business research. You can reduce incentives for phone interviews, videoconferences, or other research that doesn’t require people to leave their homes or offices or you to visit theirs; unmoderated research can also pay small amounts.

Give extra incentives to people with unique perspectives or who are willing to come in at awkward hours. Calculate the “extra” based on the conditions. If you need someone to come in tomorrow, adding an additional $20 to $40 to the basic incentive may be appropriate. A busy manager may not be willing to break up his or her day for less than $200. It’s often useful to budget for a range, and then let the recruiter up the incentive to get good candidates.

For certain people, no amount of money will be enough to encourage them to participate. For these people, you need to come up with alternative incentives. Executives may value meeting other executives in the same industry, so presenting the research as an opportunity to hobnob with peers may entice them. Charity donations are sometimes attractive, as are gift certificates to luxury restaurants or theater tickets. A luxury cruise line site had retired millionaires who liked to travel as its customers. It recruited them by giving them all-expenses-paid flights to New York. It cost the site several thousand dollars per participant, but they were able to get their exact target audience from all over the country. Merely offering the same amount in cash would not have showed the understanding and respect for the participants’ priorities that convinced them to participate.

Sometimes people are willing to participate for less than you’re offering, or even for free. But it’s not a good idea to take advantage of them. For one thing, people who do research for cheap are a self-selecting bunch: they have a lot of time on their hands, or they’re really eager to talk to you, or they need the money. The people who fit any of those criteria are unlikely to be representative of your target audience.

Recruiting Pitfalls

The Wrong People

Sometimes you recruit the wrong group. Maybe you misworded a key screener question, and everyone answered it opposite to what you had intended. Maybe you forgot a key element when determining the target audience. Maybe the recruiter always picked the minimal criteria when you only wanted a couple of people with that description. Regardless, sometimes you will mistakenly invite the wrong people. Every researcher has stories about coming into a room and realizing that it’s full of people who shouldn’t be there at all.

Preparation, a good screener, a carefully chosen target audience, and asking some key questions at the beginning of the research will minimize the chances of this situation, but it still happens. If you find yourself in such a situation, there are two things you can do: either cancel the session and re-recruit, or try to get as much information out of the group, hoping that some of their feedback will be usable. Sometimes the wrong group can be enlightening, since the comparison of answers with a group of the right people can lead to a better understanding of the whole population. Maybe your target audience isn’t so unique after all. However, when time is short and accurate results are critical, cancellation is a perfectly acceptable option. Then you can channel your efforts into getting a group of the right people.

Before you decide to re-recruit (or you start blaming the recruiter), you have to determine why the recruiting failed. In some cases, it will be really obvious—you wanted job seekers, but not people who have never had a job—but sometimes it may not be clear why a certain group didn’t fit your vision. Identify the elements that resulted in the wrong group: is it because of demographic factors? Is it because of their experience (or lack thereof) with the product? Perhaps you did not specify a key criterion (“factory workers” versus “factory workers who work on the shop floor,” for example). Or maybe your expectation of how people behave may not match how your target audience thinks. In rare cases, there may be no way to recruit the perfect group because the factors you want simply don’t exist together.

Always pay people who show up what you promised them, even if you made a mistake in recruiting them. They showed up in good faith. Likewise, pay the recruiter in full if the recruiter scheduled the wrong people and the problem lies with your screener.

No-shows

It seems to be human nature that about a quarter of any invited group won’t show up, for one reason or another. You can compensate for this by scheduling extra people and adding unexcused no-shows to your list of people not to ask again.

If you would like to guarantee a full roster, you can double-schedule every time slot. This makes for twice the recruiting and scheduling work and twice the incentive expense (since you have to pay everyone who shows up, whether or not you need them to participate in research), so it’s rarely worth the trouble. But it’s useful in certain situations, such as when a senior stakeholder plans to observe the research. You can also use the extra people for other studies if you have the resources and a secondary research project. You could have a usability test as a primary research project and a questionnaire or card-sorting task as a secondary project, since these don’t need as much interaction with a researcher as the usability test. You could even have members of the development team who aren’t observing the usability test interview the participants (provided those team members have some user research experience).

Likewise, you can schedule a “floater” for a block of time, say, three hours, to hang out in case someone doesn’t show up. However, qualified people who have two to three hours in the middle of their day are difficult to find, so this isn’t as attractive an option as it may seem at first. Floaters should be paid the proportional amount of incentive for the amount of time they spend waiting (two to three times what someone scheduled for a single slot would get), and they, too, can participate in secondary research if they’re not needed as substitutes.

If the schedule and facility rental budget permit, you can also create “makeup” slots a day or two after the initial batch of research. People who can’t make their initially scheduled time may be amenable to rescheduling.

If you’re expecting weather bad enough to close the roads, arrange an alternative day in advance. Pick a school near the study site and tell people to check whether it’s closed. If that school is closed, odds are that roads are impassable, so people automatically know they’re rescheduled for the alternative day.

Note down the names of no-shows. Unless the people warned you or the recruiter ahead of time, do not pay them and remove them from your contact list, or tell the recruiter to do likewise.

Bias

Your recruiting methods will alter the kinds of people you find. If you rely on paper flyers in your local businesses, for example, you are limiting potential participation to people who visit those businesses. That’s great if you’re doing a study on people who probably spend a lot of time in your neighborhood. But those people might not have anything relevant to say about your research question.

A truly random sample is impossible, so there’s no getting away from some amount of bias. The question is whether the bias matters for your project. Often it does not. Nevertheless, you should mind how bias in recruiting might affect the research results. Keep track of how each person was recruited and evaluate frequent sources for his or her potential to skew the results. If half of your participants come from the same place, you should consider whether that recruitment method is affecting your results.

Anonymity

Preconceptions about your company can also bias the attitudes of people coming to test with you. A famous name can be intimidating, and an unknown company or product can seem more trivial than it really is.

If you don’t want people to know your company’s name as they are recruited and scheduled, it may be useful to maintain an alternative identity. Don’t deceive people, but working through an alternative email address (say, one from a free service) and describing the company and research without giving any specifics can be useful. In general, people don’t mind if you tell them that you’d rather not reveal the name of the company or its products.

Building and Space Preparation

Although not technically a recruiting pitfall, a common problem with scheduling participants for in-person research is that the venue isn’t prepared to greet them. If they’re arriving at an office, everyone they meet should be expecting them. Security staff should know where to send them; the receptionist should know they’re coming. You can even make signs to direct them. If you are meeting in a public place (like a shopping mall or a park), make sure they have some way to coordinate on the go.

Working with a Professional Recruiter

A professional recruiter can take a lot of the headache out of doing the recruiting. Pros have access to a large number of people in a broad range of markets and can schedule them fast. They can be a great asset if you are short on time, don’t have many current users to draw on, or aren’t sure how to recruit a certain audience.

However, working with professionals is more involved than just picking up a phone and saying that you need people that match this-and-such a profile. Recruiters do not know your business or your research requirements. Careful preparation and collaboration on the part of the research team is necessary for the recruiter to get the people you need when you need them.

![]() The American Marketing Association (www.ama.org), the Marketing Research Association (www.mra-net.org), and the European Society for Opinion and Market Research (www.esomar.org) can point you toward other resources. Also check www.mkp.com/observing-the-user-experience for more suggestions on how to find recruiters.

The American Marketing Association (www.ama.org), the Marketing Research Association (www.mra-net.org), and the European Society for Opinion and Market Research (www.esomar.org) can point you toward other resources. Also check www.mkp.com/observing-the-user-experience for more suggestions on how to find recruiters.

Where to Find a Recruiter

Recruiters are often associated with companies offering a broad range of market research services, from providing special conference rooms to focus group moderation to designing and running whole research projects. If you’re in a major metropolitan area, finding one should not be hard. You can generally look up “marketing research” in your city and find half a dozen.

When choosing a recruiting firm, do some research. As with any service, ask for quotes from several different firms and request references from their last couple of user experience research clients. If you’re recruiting for usability testing, ask them whether they do recruiting for “one-on-one interviews” (or, ideally, for usability testing) and if they recruit for offsite facilities. Follow up with the references they provide and ask about the accuracy of the recruiting, how receptive the recruiter was to changes, how many people were recruited, and how specific the recruiting criteria were. If you have a specific audience, such as martial arts experts or cardiologists, ask about the recruiter’s expertise with that exact group. Different recruiters may have different areas of experience. Some have more contacts in medicine, for example, while some may have great sources in the hospitality industry.

Since recruiting may only be part of their business, full-featured marketing research companies may be reluctant to just recruit and may insist on renting out their research spaces (which can be expensive) or providing other services. If you’re only interested in recruiting, you can definitely find a place willing to specialize in it.

For small, fast user research projects, the best bet is to find an independent recruiter who specializes in recruiting and scheduling. These types of companies are rarer than the general market research services, but they exist in most metropolitan areas. If you can’t find one, ask some colleagues or check with one of the usability or human factors associations such as the Usability Professionals Association or Computer-Human Interaction Special Interest Group of the Association of Computing Machinery (ACM SIGCHI).

What Recruiters Can Provide

Every professional recruiter should handle all the aspects of finding the right people, scheduling them, answering their questions, and reminding them of their appointments. In addition, an experienced recruiter can also help you focus your research by narrowing your target audience to just to the people you’re interested in. If you are not sure about how to specify the right market for your research, ask your recruiter to help you put together a profile.

Some recruiters will write a screener for you, and in practice, they’ll often modify your screener to better fit their style and policies. You should participate in the process by requesting a copy before the recruiting begins to ensure that appropriate emphasis is placed on the elements that are of prime importance to you.

In addition to providing you with the profiles of the scheduled participants, many recruiters are willing to take notes about the responses of people who do not get scheduled. Although this tally does not qualify as a survey, it can be interesting information since it can reveal unexpected patterns in your target audience.

Many recruiters will administrate incentive payments, too, cutting checks or providing cash or gift cards as appropriate. In addition, larger recruiting companies can recruit in various geographic markets for you.

What Recruiters Need from You

The most important thing to provide a recruiter is a complete audience description. They will be happy to recruit based on just about any description you give them, but since they don’t know your business, they can’t filter based on unstated assumptions you have about your audience. If your description isn’t sufficiently specific, you’re likely to get people you don’t want. If you say that you’re looking for casual gamers without saying that you want them to have at least some familiarity with online games, the recruiter may get you a bunch of people who play cards. Be as specific as possible. If you’re looking for white-collar workers, define what you mean by “white-collar workers.”

Include a list of whom to exclude. What are industries that present a potential conflict of interest? How much past participation in research is too much? What companies make products competing with yours?

Budget enough time (many commercial vendors need two weeks minimum) and avoid changing the parameters of the recruiting in the middle. Changes are a hassle for the recruiter, and they’re likely to pass the cost of that hassle on to you. If you cancel, be prepared to pay at least part of the incentive fee (all of it if you cancel on the same day) and all the recruiting costs.

Suggest where to get qualified candidates. If you already have a list of customers, such as people who have signed up for a newsletter, and you can filter it for your geographic area, offer the recruiter the list (though be aware that list members will likely know your product and have positive preconceptions about it; otherwise, they wouldn’t have signed up for the newsletter). If you don’t know where to find candidates, you should give the recruiter as much information as you can about where to look for the target audience and how prevalent you expect them to be in the population as a whole.

Provide direction for how to handle marginal candidates. Clearly note which qualities are flexible and how flexible they are. (“We prefer 25- to 35-year-olds, but will accept people between 20 and 40 if they match all the other criteria well.”)

Describe the research to the recruiter. This will help the recruiter understand how to answer questions and may give him or her additional ideas for how to structure the target market description. Is it a series of groups? Is it a series of one-on-one interviews? Will it be done at a special facility? Will it be at the participant’s house? Will it be focused on their attitudes, their experiences, or how well they can use a prototype? Tell the recruiter how much of this information is appropriate to tell the participants.

Finally, explain any terminology that’s necessary so that the recruiter can interpret people’s responses appropriately. If you’re looking for IT managers who regularly buy “hot-swappable, fault-tolerant, low RF, Mil-Spec, U-racks,” you should probably tell the recruiter something about what all those words mean. The recruiter probably won’t need to use these words in conversation, but knowing what they mean will help the recruiter understand the questions he or she is asking.

What They Cost

In 2012, recruiting in major U.S. metro areas typically costs between $100 and $150 per participant scheduled, excluding any incentives you pay participants. Consumers fall on the lower end of the scale and professionals on the upper end. For common groups with few restrictions, such as grocery shoppers with kids, it may be even cheaper. For other groups, such as human resources vice presidents who run organizations with enterprise-wide knowledge management systems, the cost may rise significantly.

Other services, such as screener writing or response tabulation, can be rolled into the whole cost or charged on an hourly basis, with hourly rates of between $75 and $150.

When There Are Recruiting Problems

Don’t accept bad recruiting. If it’s clear that the priorities and questions in the screener were not strictly followed, ask for your money back or for some better recruiting. First, however, make sure that your audience description did not allow the recruiter to interpret it in a way you hadn’t intended. Most recruiters, although not elated by the prospect, will re-recruit participants who didn’t fall into the target description.

Further, as a final courtesy to the recruiter, tell him or her when a participant was particularly good or bad. This will help the recruiter in future recruiting efforts.

Gaining Informed Consent

Gaining informed consent is the cornerstone of ethical research practice. Research participants must understand what you are asking them to do and freely agree to participate. Getting participants’ informed permission before starting research protects you as well as the research participant. Starting a research relationship off with full disclosure minimizes the chance that participants will wonder later if you took advantage of them in any way. This is particularly important in situations where people may feel as if a large company is going to profit from their participation.

It is your responsibility to give participants all the information they need in a way that makes sense to them. This is usually done by having participants read and sign a printed consent form. Consent forms typically include:

A brief description of the research activity and its motivation

This is a usability study of Forkopolis, a website devoted to selling forks. It is intended to improve shoppers’ experience with the site. In this study, we will ask you to perform specific tasks using the website and tell us what you think.

An explanation of what data you want to capture and how you plan to use it

We would like to video record this usability test and share the results with our team for the purposes of improving the site. We will not share your name or any other identifying information with anyone else.

If you are planning to take photos, or video/audio record, the form should also ask participants to indicate which media they will allow you to record and to release their rights to it.

Please check the box if

[ ] you give us permission to record video and share it with the team.

[ ] you give us permission to quote any verbal statements you make during the test in our reports.

An assurance that the participant can leave the study at any time without penalty

You are free to leave at any time. If you end participation, we will delete any video we have captured and notes that we have taken.

An encouragement to the participant to raise any questions or concerns about the study as soon as possible

Please let us know as soon as possible if you have any questions or concerns.

Area for participant’s printed name, signature, and date of signing

I understand and agree.

Name _________________

Signature ______________

Date__________________

Over time, researchers tend to develop consent form wording and formats that work well for them, adapting a standard template to the needs of each project. The best consent forms are short and straightforward. Keep the form under a page if possible and avoid legalese or any unnecessarily formal language.

It can be helpful to think of a “consent” as a process, rather than a document. If a participant initially okays video recording but at the end of the interview asks you to delete the video, take that request seriously. Of course, you can—and should—ask why. Perhaps the participant has specific concerns that you can mitigate. But if the participant remains certain, honor the request and delete the video immediately. For the same reason, it can be a good idea to ask participants at the end of an interview if there is anything they said or showed you that they would not want shared.

If you are using a specialized research facility for focus groups or usability tests, the personnel there can handle consent forms as participants show up. Otherwise, you should get them signed after you introduce yourself and everyone gets comfortable, but before before you ask the first question or snap the first photograph.

Minors. In much of the world, people under the age of 18 cannot legally consent to research. Their parents or other legal guardians must agree on their behalf. If your study involves minors, consent is a two-step process. First, create a consent form for the guardians specifying that they are consenting on behalf of a minor. Second, make sure to also get informed consent from the child or teenager. If the participant can read, make sure your consent form is at a suitable reading level. If the participant is too young to read, read the consent form aloud and ask questions to make sure the child really understands what’s going on. Even though a child can’t legally consent, making sure that he or she understands and agrees to participate is the right thing to do.

Illiteracy. You can’t depend on written forms when you know or suspect that your participants can’t read. In those cases, ask someone who can read—who’s also not associated with the study—to serve as a witness ahead of time. Then just read the consent form aloud instead of handing it to the participant. Pause periodically so that the participant has time for questions. Ask the participant to make an “X” or other mark to indicate acceptance, and the witness will sign off to confirm that the participant agreed to the terms on the form.

![]() For template consent forms and more resources on informed consent, visit www.mkp.com/observing-the-user-experience.

For template consent forms and more resources on informed consent, visit www.mkp.com/observing-the-user-experience.

Interviewing

Most of the research described in this book boils down to one technique: the interview. Observation is critical, but to really know the user’s experience, you have to ask him or her about it, and that’s an interview. User research interviewing differs from the kind of interview an investigative journalist or a prospective employer would hold. It’s more formal and more standardized, and as a kind of nondirected interview, tries to minimize the perspective of the person asking the questions.

The Interview Structure

Nearly every user experience interview, whether it’s a one-person lunchtime chat or a ten-person focus group, has a similar underlying structure. It’s an hourglass shape that begins with the most general information and then moves to more and more specific questions before stepping back for a bigger perspective and concluding with a summary and wrap-up. Here is one way of dividing a standard interview process into six phases.

1. Introduction. All participants introduce themselves. In groups, it’s important to know that the other people in the group are somewhat like you in order to feel comfortable, so a group introduction emphasizes the similarities between all the participants, including the interviewer. In contrast, an individual interview introduction establishes the role of the interviewer as a neutral, but sympathetic, entity.

2. Warm-up. The warm-up in any interview is designed to get people to step away from their regular lives and focus on thinking about the product and the work of answering questions.

3. General issues. The initial product-specific round of questions concentrates on experiences with the product, as well as attitudes, expectations, and assumptions about it. Asking these kinds of questions early prevents the assumptions of the product development team from skewing people’s perceptions. Often, the product isn’t even named during this phase.

4. Deep focus. The product, service, or idea is introduced, and people concentrate on the details of what it does, how it works, whether they can use it, and what their immediate experience of it is. For usability testing, this phase makes up the bulk of the interview, but for site visits or exploratory interviews, it may never enter the discussion.

5. Retrospective. This phase allows people to evaluate the product or idea in a broader light. The discussion is comparable to the “general issues” phase, but the discussion is focused on how the ideas introduced in the “deep focus” phase affect the issues discussed earlier.

6. Wrap-up. This is generally the shortest phase of the interview. It formally completes the interview so that the participants aren’t left hanging after the last question and returns to administrative topics.

Do a dry run with every new interview script. Run through it with a colleague or a sample participant, complete with all recording devices and prototypes, and then revise it appropriately.

Nondirected Interviewing

A famous scientist once asked the following question on a survey:

Does your employer or his representative resort to trickery in order to defraud you of a part of your earnings?∗

This is a leading question. Before you read on, think about what makes this a leading question. What in it implies a “right” answer? What is the actual information the author is trying to elicit? What would have to be different for the question to not be a leading question?

The scientist who wrote it was Karl Marx, and he clearly had an answer that he was expecting, and it wasn’t “no.”

Leading questions are the bane of all social research. They inject the prejudices of the person asking a question into a situation that should be completely about the person answering it. But avoiding directed questioning is easier said than done. It requires a constant vigilance on the part of the person asking the questions and expertise with nondirected interviewing.

Nondirected interviewing is the process of conducting interviews that do not lead or bias the answers. It minimizes the effects of the interviewer’s preconceptions in order to explore the user’s thoughts, feelings, and experiences.

The Neutral Interviewer

As the person writing and asking the questions in a nondirected interview, your job is to step outside everything you know and feel about your product. Forget all the hard work and creativity. Put away all hopes for success and all fears of failure. See it in a neutral light, as if it’s not yours at all.

This seems harsh, but it’s necessary in order to be able to understand the feedback people give you, both positive and negative, and be able to relate that to the process of making the product into what they want and need, not what you think they want and need. Otherwise, you’ll always be seeing either the silver lining or the cloud at a time when you need to be seeing both.

Zen aside, asking questions so as to not bias the respondent’s answer involves a lot of self-imposed distance and a rigorously critical examination of your assumptions. This can be especially difficult when you are intimately familiar with or emotionally invested in the product under examination. At first, it’s going to feel like your questions take too much energy to formulate and sound stilted. Experience will clarify which questions lead people and how to phrase questions neutrally. Eventually—when you’ve achieved nondirected question enlightenment—your questions will sound natural, analysis will be easier, and the unbiased answers you get will give you greater confidence in your results.

Presenting a Neutral Face

Asking nondirected questions has been called an art of “talking without really saying anything.” Interviewers need to encourage people to talk without telling them what to say.

Often, that means keeping quiet and letting the participant think. When you’re tempted to interrupt, try squeezing your hands together instead. Or, when appropriate, take a sip from a glass of water instead of talking.

Experienced interviewers also have a repertoire of generic conversational cues. Some of them are nonverbal, such as “uh-huh” and “mm-hm.” Others are sympathetic but bland, such as “that’s interesting” and “oh, really.” Others, such as “Can you tell me more about _____?” ask for more detail, but don’t specify any correct answer.

Developing verbal cues is especially important for phone interviews, since there is no body language to communicate your engagement. In person, leaning forward and nodding occasionally can help. Whether verbally or nonverbally, it’s important to make sure people know you are paying attention to them.

Composing Nondirected Questions

Most important, every question should be focused on the person answering it. It should focus on experience, not extrapolation. Our understanding of our own behavior rarely corresponds to how we really behave. When we try to put ourselves into others’ shoes, we idealize and simplify. That’s useful in trying to understand people’s ideals, but it’s rarely useful in understanding their behavior. A question such as, “Is this a useful feature?” can be easily misinterpreted as, “In the universe of all things, do you think that someone somewhere could find some use for this feature?” Even taken at face value, the potential for misunderstanding makes all replies questionable. “Is this feature valuable to the work you do right now?” clarifies the perspective.

Similarly, questions should concentrate on immediate experience. People’s current behavior better predicts their future behavior than do their predictions. If you ask people, “Is this interesting to you?” they may imagine that at some point they could find it interesting and say yes. But some things that seem interesting in theory are quite different from things that people will remember and return to. If they find something compelling right now, they’re likely to continue to find it compelling. Thus, the responses to “If it were available today, would you use it? Why?” will be more useful.

Questions should avoid judgmental language. The person answering the question should not think that you’re expecting a specific answer or that any answer is wrong. You can (and should) state this explicitly, but it works better if the question reinforces that view. “Don’t you think that this would be better if it was also available on smart phones?” implies that the person asking the question thinks will disapprove if they hear otherwise. “If this feature were available tomorrow on smart phones, would you use it?” doesn’t imply an expected answer (though it’s a binary question, which we’ll describe later). An even better question would be, “Is there any other way you might use a feature like this?” and then ask about smart phones after they’ve stated their initial thoughts.

Focus questions on a single topic. An “and” or an “or” linking two ideas is ambiguous. It’s hard to tell which concept the response addresses. Divide a question like “How would this product be useful to you in school or at work?” in two.

Keep questions open-ended. If forced to choose, people will pick something, even if none of the options match what they believe. “Which feature from the following list is most important to you?” assumes that there are features that are important, and it assumes that there is one that’s more important than any other. A better way would be to say “Rate from 1 to 5 how important each of the following features is to you, where 1 is least important and 5 is most important. Put 0 if a feature is completely unimportant. Write down any features we may have missed.” Or don’t rate the features. Instead ask, “Does the product do anything that’s particularly useful to you? If so, what is it? What makes it useful?”

Avoid binary questions. Binary questions are of the form “yes/no” or “true/false” or “this/that,” and they force people to make a black-and-white choice when their attitude may not lie near either extreme. “Is this a good product?” misses a lot of subtlety. Although it may be nice to quickly check people’s off-the-cuff opinions, it’s more valuable to know what they find good and bad about the idea, rather than just if the whole thing seems good or bad. “What, if anything, do you like about this product?”

Running a Nondirected Interview

There are a number of ways to increase the quality of the responses in a nondirected interview.

Define terms. “That thing” can refer to a button, a feature, or the whole site. Personal definitions of words differ from the dictionary definition and the development team’s definition. Someone may speak of a simple function as a “module,” whereas the development team may call complex clusters of functions “modules.” When using a technical term, make sure that you clearly define it first. Whenever possible, use the respondent’s definition of a word (even if it’s not how you use it), but make sure that you understand what that definition is first (which may mean asking the respondent to define it). This is especially important in group interactions, where everyone can come in with different definitions.

Don’t force opinions. There are topics about which we just don’t have an opinion. We may have never thought about them, or we may not have enough information. When asked for an opinion, most people will express one. But it’s not going to be carefully considered or deeply held. Before framing a question in terms like “Would this be better or worse if…,” try to gauge whether the participant has any knowledge of “this.”

Restate answers. Bouncing the respondent’s answer back at him or her using different words can cut through problems with questions. It clarifies terminology and verifies that you and the participant understand each other. Immediately after someone has finished a thought, you can say something like “So I hear you saying that…” and state what you just heard using different words. Restating answers requires a little extra care because restatements themselves can lead the discussion. If you have a bias, it’s easy to subtly restate in a way that better fits your assumptions.