Image Resolution

Resolution is measured in lines and pixels—the microdots on a computer's LCD screen, which you can see with a magnifying glass, or when you accidentally spit on the screen and notice little red, blue, and green dots in each pixel. Each of these three colors changes value, shaping the hues you see on-screen. The more pixels you have on-screen, the more detail you can see. These pixels are arranged in lines. Lines are measured top to bottom, whereas pixels are measured along the lines, left to right. As a point of comparison, the miniDV format contains about 480 lines of resolution with about 720 pixels per line, whereas 1080 HD video contains 1,080 lines with 1,920 pixels per line. In addition, the P in 1080 P indicates a progressive scan (where the image is presented fully), as opposed to a 1080i (which indicates alternating interlaced scan lines used in broadcast television).

In film, 35 mm provides about six times the resolution of HD video in its original negative (6,000 lines of resolution), whereas a projection print has about 2,000 (for 2 K projectors). The figure varies; one source places film resolution at 3,112 lines with 4,096 pixels per line. So 1080 × 1920 high-definition video provides just over 2 million pixels of resolution, whereas film contains 12 million pixels of resolution!

The exposure index (the optimum ISO setting to expose the image) for miniDV is about 200, whereas HD is around 300. Film contains an exposure index of 800.

Filmmakers interested in digital film find the RED Scarlet and Epic cameras fascinating because their resolution and exposure index approaches the quality of film. The resolution of the 3 K Scarlet contains 3072 × 1728 pixels (that's 5.3 million pixels, over twice that of standard HD).

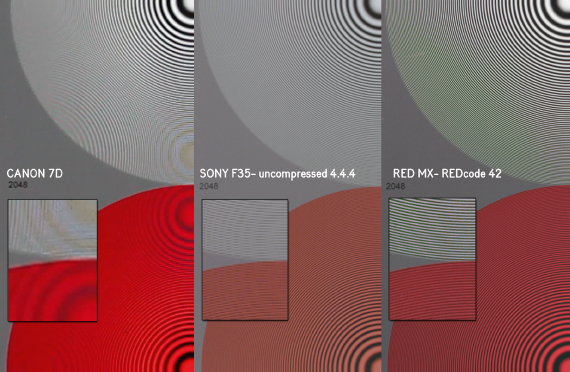

It must also be mentioned that one of the main debates circulating around DSLRs are some manufacturers’ slow CMOS chips (requiring “line skipping” in the sensor's signal processing, resulting in line bending during camera pans). The RED company, which created one of the first digital cinema cameras, the RED, followed by the new Epic and Scarlet models, did tests comparing its Mysterium-X sensor to the Canon 7D and Sony's F35 (see Figure A1.1).

FIGURE A1.1

As can be seen, the zone test reveals high amounts of pixilation in the Canon, with less in the Sony F35, while the RED provides nearly a flawless image. Debate went back and forth on Reduser.net, some stating that it's an unfair test and that professional work is being shot with Canon 5Ds and 7Ds, for example. RED owner Jim Jannard weighed in by stating that he's just putting facts out there and wants camera users to decide: “I guess the proliferation of misinformation about what the DSLRs can and can't do triggered a bit of frustration. I just believe that ‘good enough’ isn't a professional mindset.” He, among others, feel that professionals should be concerned with image resolution.

(<http://reduser.net/forum/showthread.php?t541220&page53>, accessed February 25, 2010)

Barry Green, testing the image quality of several DSLRs by recording resolution charts (see Figure A1.2), argues on DVXuser.com that many DSLRs are cheating their resolution:

[T]he [Panasonic] GH1, the [Canon] 7D, and the 5D Mark II all look like they're rendering incredibly sharp, highly detailed images, but they're not. In reality, according to the resolution charts, they're rendering images that fall somewhere around a standard-definition camera, and maybe a 720 P camera. Any additional “sharpness” you see in the image is fake—it's aliasing, it's smoke and mirrors, it's image contamination.

Rarely will you see such obvious image contamination as on a resolution chart. In a real-world image, it may be much harder to spot what's “real” and what's aliased “fake” detail. To an untrained eye, a heavily aliased image might even look good. Before you had the chart explained to you, which image looked “sharper”—the one with the blur, or the one with the vertical lines? Granted, neither of them is a perfect representation of what they're supposed to look like, but which of these images looks more like an accurate representation of the third chart?

Similar to the arguments found on Reduser.net, users on Prolost.com argued back and forth about the merits of shooting HD with DSLRs. Some claimed (correctly) that they're first and foremost stills cameras with video added as an afterthought.

Ted Schilowitz, the number two person at RED, said in a personal interview that RED is concerned about resolution because it wants to create digital film, a form that's designed to replace analog film. “Our world is not about making sacrifices, our world is giving people the tools to make really, really good pictures. So, the Scarlet, with a 3 K sensor in it, the body is under three thousand bucks. A set of prime lenses, they're super fast, are under five thousand for the whole set. And the Scarlet is a real RED camera right? It's not an SLR that is cheating and doing video scaling to get your 1080 P image. This is doing 3 K RED code raw, just like its bigger brother the RED One.” They're setting themselves up for the 4 K projection world of future cinema.

FIGURE A1.2

Barry Green's resolution chart comparing the resolution of a video camera to a DSLR. The third image reveals the original chart.

However, despite resolution tests, the most important point to make out of this argument is not the resolution of the camera or whether or not it's aliasing, but what the image feels like to the audience. And because the Scarlet hasn't been released at the time writing was completed for this book in early summer 2010, it's really a moot argument. Cameras are tools for storytelling. Stephen van Vuuren, who created the film Outside In (a movie on Saturn composed of still imaging techniques), noted on the Prolost.com site how he was concerned about the resolution tests, and debated whether or not to get a Canon 7D. However, after seeing Vincent Laforet's Nocturne,

I pulled the trigger. I absolutely knew about the [resolutionaliasing] issues and found it easy to figure out when the problem occurs (see my test clip [http://vimeo.com/sv2studios]). Shoot fine horizontal detail stopped way down with high shutter speed handheld—yowza.

However, after hours of shooting with my 7D, I've yet to see this again. Occasionally I see some mild aliasing.

But here's the most important thing to me—non-technical and technical people I've worked for years watching my Canon XL-1, DVX100a, HV30 and other footage respond “Wow” upon seeing 7D on a native 25” 1080 P monitor.

I personally have not been this excited in a camera since I bought [a] top-of-the-line Chinon Super 8 camera in 1988. I love it—the camera excites me. People who watch the footage go “wow.” It cost $1,900 with a lens, ready to shoot 24p 1080p images with Super 35 mm DOF with lovely low light and dynamic range. Yeah, it has a few technical issues. But who cares. I don't, nor do the people watching.

Van Vuuren, like many DSLR shooters, really doesn't care that much about resolution tests, and the minutia of such geek details are really lost on them because they understand that the story comes first and if the weaknesses can be overcome, then good-quality cinema projects can be created. Philip Bloom and Shane Hurlbut, ASC, use Canon DSLRs to make their movies despite such limitations because, for them, like van Vuuren, clients are wooed over by the wow factor of the image. They feel the image is good enough for professional use—even George Lucas.

When Philip Bloom was invited to Skywalker Ranch to show off the capabilities of DSLR cameras, he shot around the ranch using a Canon 5D and 7D, and then screened the results on a 40-foot screen for Rick McCallum and George Lucas. They did not complain about the footage, but were impressed.1 Lucasfilm used DSLRs in some of their work for Red Tails, a World War II film focused on an African American fighter squadron.

One of the reasons people like to shoot on HD DSLRs as compared to standard HD cameras is their ability to shoot in low light. Matt Buchanan, a reporter for Gizmodo.com, discusses how camera companies marketed the quality of their image by pixel count but have since changed: “However it began, ‘amazing low-light performance’ is now a standard bullet point for any camera that costs more than $300 (even if it's not true).”2 In either case, pixel resolution in DSLR cameras is only for still-image mode; the pixel count in 1080 P is the same, no matter the high megapixel count advertised, because when cinema makers shoot in video mode, it'll be 1920×1080 (for 1080 resolution). The ISO exposure capabilities for low-light sensitivity and low signal-to-noise ratio are advantages with DSLR cameras.

It comes down to this: someone shooting on a RED Scarlet, for example, can shoot a project that doesn't look that good, whereas someone shooting on a standard HD camera can get a cinema look if he knows what he's doing. The resolution doesn't create a cinematic look; the cinematographer's eye does that. That's why many cinematographers look at the lighting in the world around them and study master painters because they know how to use light and color to set the mood of the image. When shaping the mood with light and shadow, the cinematographer crafts an illusion of beauty on-screen, which results in what we call the “film look.” The film look, in other words, is subjective. It's what we see in cinema, shot by cinematographers who are helping to shape the mood of the story by using light and shadow, lenses, filters, and so on to be able to craft the cinematic mood of a scene.

1Bloom, P. The tale of Lucasfilm, Skywalker Ranch, Star Wars and Cnon DSLRs on a 40 foot screen!<http://philipbloom.net/2009/12/12/skywalker/>, accessed February, 25.2010.

2 Giz Explains: Why ISO Is the New Megapixel. <http://gizmodo.com/5470334/giz-explains-why-iso-is-the-new-megapixel>, accessed March 2010.