Large sensor cinema snuck up on us all. My first short movies were shot on the Canon L2 Hi8 mm video camera. When I was doing doctoral work at NYU's Tisch School of the Arts in the mid- to late 1990s, I enrolled in the NYU boot camp one summer, and we shot on 16 mm black and white film with no sync sound—Arriflexes that had three fixed lenses that you could rotate into position. After that, I purchased the first generation Panasonic DVX100 24p miniDV camera and shot two fiction shorts and several documentary projects. When I consulted with reporters in Spring 2008 at The Christian Science Monitor, our budget allowed only for consumer HD cameras (a mix of Panasonic and JVC tapeless cameras), and they cost around $1,200. Before shifting to DSLRs, I shot my latest festival documentary on a Sony A1U HDV miniDV camera, a $2,200 camera, nearly the price of a Canon 5D Mark II body! And none of those cameras matched the image quality of the Canon Rebel T2i for $600!

I know digital video.

None of my footage from these cameras looked as good as the two-minute rolls of film I shot on that Arriflex at NYU. Not even close. The smooth, creamy shots were unlike anything I've ever seen on video. The sharpness of the glass was incomparable. But I lived with shooting on video because it was affordable, and artistic sensibility—that cinematic feel I had previously seen in 16 mm film—was compromised due to budget.

Until now.

Once I picked up the Canon 5D Mark II, there was no going back. The footage coming out of the camera—if not the same as those shorts I shot with an Arriflex—was the best thing I've seen since then. It was cinematic. I, like Philip Bloom, dismissed the camera at first because of the lack of controlling aperture.

But in the fall of 2009, I started watching videos on Vimeo by DSLR shooters. The stuff looked good. I wanted one. I did more research and convinced my colleagues at Northern Arizona University's School of Communication to get one—the Panasonic GH1 (the only other serious contender at the time for around ~$1300). One of my students, Shannon Sassone, shot her short fiction project with it in my intro video production class. She was amazed at the quality of the image. And I became convinced that DSLRs could be used in the classroom.

Later, I decided to write a book proposal that would address the cinematic needs of these student shooters, as well as for independent filmmakers and video journalists who saw the potential of these cameras but didn't know where all the resources were to make effective use of DSLRs as cinema cameras. I wanted to bring together some of the best thinkers and practitioners practicing this form of cinema—from Philip Bloom, who pioneered the sharing of information about DSLRs on his blog; to Rii Schroer, who is primarily a photo journalist who wanted to make movies with this camera; to Shane Hurlbut, ASC, who had access to nearly any camera in the world but wants to shoot films with the Canon 5D Mark II.

It's one thing to ignore shooters who get excited about putting up test shots online. It's another thing to look at Philip Bloom's San Francisco People, Cherry Blossom Girl, or Skywalker Ranch, or even his Salton Sea Beach (shot on a Canon Rebel T2i), and not realize that there's something going on here—something different from the kinds of video we've seen over the past 15 to 20 years.

Then Philip Bloom announced 10 million views on his website as of June 1, 2010, and we're not talking about a celebrity site, but a working man's view of HDSLR cinema and how he's doing it (see <http://philipbloom.net/>). Other blogs sprouted up (which I highly recommend checking out): Shane Hurlbut: Hurlbut Visuals (<http://www.hurlbutvisuals.com>), Jared Abrams: Wide Open Camera (<http://wideopencamera.com/>), PlanetMitch's blog: <http://blog.planet5d.com/>, Vincent Laforet: <http://blog.vincentlaforet.com/>, and Dan Chung's DSLR News Shooter (<http://www.dslrnewsshooter.com/>). All of these sites reveal a democratization of the cinema look, an inside peak at how to do good work.

And when Lucasfilm jumped on board, the tremor became an earthquake. As Shane Hurlbut, ASC, is fond of saying, Canon knocked over the applecart, burned it up, and decided to make applesauce. How cinema and television are being done is starting to change. Hollywood has embraced the new aesthetic offered by these cameras.

The season finale of House MD (2010) was shot on a Canon 5D Mark II. “We started testing on episode 19, which I was directing,” Greg Yaitanes says in an interview with Philip Bloom.1 “We would run the 5D next to our film cameras just to see how the 5D was reacting to our lighting, what our sets looked like, how actors looked, anything we needed to be aware of. And we were very happy with these tests.” Everyone was surprised by how good the image looked. Everyone on the production and postproduction team agreed—including those handling special effects; even the studio executives said it was good enough for broadcast, Yaitanes explains.

I'm not trying to create a film aesthetic. I'm trying to create its own aesthetic. I want it to be its own look, its own style.

In the end, Yaitanes said it looked “gorgeous … It allowed us to tell a story that we never told before.” The HDSLR camera changed how the story was told. There was no examination of test charts. There was what they saw on-screen, and there was the emotion of the story.

Yaitanes embraced the aesthetics of the camera. And despite banding issues—which does tend to occur when the camera overheats—he and his team didn't let that bother them. “We struggled a bit with banding … That was every once in a while and frankly it's part of a look,” Yaitanes says to Bloom. “You can try and fight these things away and wish they weren't there, but then you're just comparing that aesthetic to something else. I'm not trying to create a film aesthetic. I'm trying to create its own aesthetic. I want it to be its own look, its own style. If there's some banding … some motion blur, then for me, who cares? I feel like the story trumps all. These are, again, tools. These are, again, things that give you a look.”2

If anything, I hope this book shows how you can develop that cinematic look—if not the look of film, then something else that looks as cool. When Yaitanes went to film school, there was only film. But he wished that it “was not the only medium in which people would look at [motion pictures]. Back then no one would take something you shot on video seriously in terms of a narrative.” Conventional video just didn't have an alternative look that felt aesthetically strong.

But that has now all changed. The DSLR cinema movement embraced a new kind of digital video aesthetic, a cinema aesthetic made possible by an HD codec combined with a large sensor, small form factor, and interchangeable lenses. Now we have many choices of large sensor cameras. Some of these are DSLRs, some are video cameras with Super S35 mm or micro 4/3 sensors—all with interchangeable lenses and all manufactured because of the DSLR cinema movement (and perhaps with a bit of influence from RED cameras). But what began as a 30 fps video on a stills camera (Canon 5D Mark II) designed for print journalists needing the convenience of shooting “a little bit of video” to supplement their in-the-field assignments for newspaper websites has now become a tool for cinema.

With the release of 4 K cameras and professional large sensor cameras over $10,000, many professionals will likely steer away from DSLRs, but many independent filmmakers, students, video journalists, and documentarians will all continue to use DSLRs because the price is right and the cinematic image is comparable to the higher-end pro cinema cameras costing thousands more.

At the same time as these higher priced cameras become predominant, the next cinematic evolution will be what many of us have asked for in the original RED Scarlet (announced in spring 2008) and later in DSLRs (fall 2008)—shooting RAW on a budget (under $3,500). This next year is when it's happening. Joe Rubinstein and Elle Schneider created the Digital Bolex camera (<http://www.digitalbolex.com/>), announced at the SXSW film festival in Austin, Texas in March 2012—the Kickstarter campaign hoped to raise $100,000 to get the first 100 production models built. Within a day or two of the announcement – with a nudge from Philip Bloom – they received over $260,000! This indicates a strong desire on the part of independent filmmakers to shoot RAW. Schneider's short film, One Small Step (2012) was shot on an early preproduction model and premiered at Cannes Film Festival (Short Film Corner) in 2012 (see Figure 16.1).

FIGURE 16.1

A still from Elle Schneider's One Small Step, a short film shot on an early preproduction model of the Digital Bolex D16, a 16 mm camera that shoots in RAW.

(Image courtesy of Digital Bolex, trailer at <http://www.digitalbolex.com/videos/trailer-one-small-step/>.)

The camera is based on the original 16 mm Bolex (made in Switzerland) so popular in the 1960s and 1970s. In addition, they're using a CCD sensor designed by Kodak, a similar chip Rubinstein discovered in the Swedish company's sleek Ikonoskop 16 mm camera. The telling sign of the oncoming RAW revolution occurred when Philip Bloom tweeted a picture of himself holding an Iknoskop and stating that his “favorite image from a camera at the show? Probably the ikonoskop. Lovely! Hope to shoot with it soon!”

(<https://twitter.com/#!/ikonoskop>). The video I saw on monitors at the Ikonoskop booth at NAB certainly revealed a strong film aesthetic. A promotional video directed by Thomas Gangalter, for clothing design company, Co was shot on an Ikonoskop (see Figure 16.2).

FIGURE 16.2

A still from Thomas Bangalter's poetic promotional for the clothing company, Co. Take note of a wide range of latitude in the desert landscape, with exposure on the face as well as on a blue sky and detail in white clouds.

(video at: http://co-collections.com/ss12.php)

It reveals a wide range of latitude in a desert landscape, with exposure on the face as well as on a blue sky and detail in white clouds. But for over $9,000 it's still in the same price range of the higher end cinema cameras. Rubinstein and Schneider, however, want a simple camera priced at the right price. They plan to release their digital Bolex in fall of 2012, with a wider market in 2013 for under $3500.

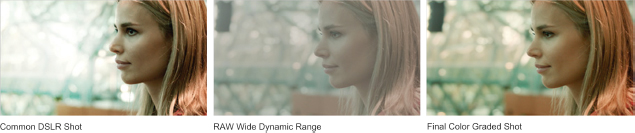

Just a month or so after the South-by announcement, Black Magic Design—the maker of quality production and postproduction hardware and software (such as DaVinci Resolve)—announced their own cinema camera that shoots 2.5 K RAW for under $3,000. The promise of RAW includes a wide latitude of exposure ranging from 12 to 14 stops—the same as film (see Figure 16.3 for RAW production still comparison).

And more recently, Weisscam announced their own version of a RAW camera, the T-CAM (<http://www.weisscam.com/products/t-cam/features_t1.html>).

The DSLR cinema movement embraces a new kind of digital video aesthetic, a DSLR cinema aesthetic made possible by an HD codec combined with a large sensor, small form factor, and interchangeable lenses.

The future will be about the film look, rather than being limited by the amount of exposure needed. The gloves are being thrown down and new technologies are coming out that make filmmaking cheaper and cheaper.

FIGURE 16.3

Black Magic Design's promotional material includes a series of stills comparing the lower range of exposure latitude on a DSLR to their RAW camera. Take note of the gradual shadow falloff in the color graded shot, as well as the details found in the highlights in the background in contrast to the blown-out highlights and sharper falloff of shadows in the DSLR shot. This is what reveals the power of RAW when utilized for a cinematic look.

(Image courtesy of BlackMagic Design <http://www.blackmagic-design.com/products/blackmagiccinemacamera/> ).

Because of the cheaper costs, filmmaking is no longer just for the Hollywood elite, but for you and me, the independent filmmakers, as well as event video shooters, students, video journalists, documentary filmmakers—the do-it-yourselfers who have been desiring cinematic quality on an affordable camera but had to simply make do with miniDV and prosumer HD cameras that just didn't cut it due to their fixed lenses and small sensors.

We can now gear up for a cinema-type project for as low as $2,000 or less and not worry that our vision's being compromised. There is no excuse to shoot crappy-looking movies. You can still shoot bad images with these cameras, but that'll be due to a lack of skill, and not the camera.

I hope this book helps you make the best-looking movie on the lowest possible budget.

It can be done. And you can do it.

1Bloom, P. Greg Yaitanes ‘House’ Interview transcription. Transcription by Oli Lewington., <http://philipbloom.net/other-stuff/case-studies/greg-yaitanes-house-interview-transcription/,accessedJuly2010>.

2Bloom, P. (April 19, 2010). In-depth interview with Greg Yaitanes, Executive Producer and Director of ‘House’ Season Finale shot on Canon 5DmkII, http://philipbloom.net/2010/04/19/in-depth-interview-with-executive-producer-and-director-of-house-season-finale-shot-on-canon-5dmkii/, accessed April 20, 2010.