A Day at the Races (2010), directed by Philip Bloom, United States, 6:00 min.

Technical data: Shot on a Canon 7D with PL Mount in a neutral picture style with Cooke S4 25 mm and 100 mm lenses and a Tokina 11–16 mm lens. Audio was recorded on a Zoom H4n with a Rode shotgun mic on a boom. The 7D was also modified with a 6 × 6 Mattebox and 0.9, 0.6, and 0.2 ND filters. Edited with Final Cut Pro. Color grading with Apple Color.

A Day at the Races is located at http://vimeo.com/9978341.

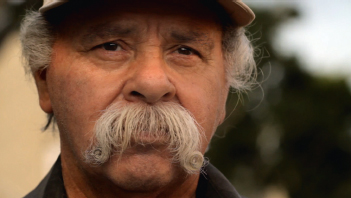

FIGURE 10.1

Still from A Day at the toes directed by Philip Bloom, showing off his trademark close-up of people's faces.

(©2010 LumaForge, LLC. Used with permission.)

Some of the greatest training for people to learn to shoot fast and shoot efficiently is to work news.

MEETING PHILIP BLOOM

Bloom, hailing from England, arrives late at Venice Beach's famed Sidewalk Café, where you can find a Louis L'Amour hamburger on the menu, as well as homeless teens with their dogs intermingling with circus act characters roaming along the boardwalk. But he's always jolly and can win you over in moments with his charm. Bloom came out of the ranks of Sky Television in England. He begged to be a camera operator and actually found his break when a sound crewmember left. He filled the opening and Bloom says he “learned to shoot from some of the best cameramen I've ever worked with.” He also learned to work efficiently and quickly by shooting news. “I would have to say that some of the greatest training for people to learn to shoot fast and shoot efficiently is to work news. Because you really have to get stuff done fast,” he notes. “I will walk into a room and it is almost like a Terminator-style scan,” he quips. “I'll look around the room and within about 30 seconds I will put any additional lighting where the subject is going to be and where the camera is going to be.” He stayed with Sky Television for 17 years, traveling the world producing documentaries for his last three years at Sky. “It was great fun,” he smiles.

After leaving Sky, he went independent. And found DSLRs. But he first balked at their potential. He tossed the Canon 5D Mark II aside. After seeing some footage over the summer of 2009, he began to change his mind. “Initially I thought the weaknesses outweighed the strengths, but by progressively using them, and with new cameras coming out and more importantly with new firmware coming out, it feels like it is going the other way and the strengths are outweighing the weaknesses,” Bloom explains.

FIGURE 10.2

Still featuring Ishan Tankha from a 90-second spot, “Voices of Change” directed by Lucy Campbell-Jackson and shot by Philip Bloom on a Canon 5D Mark II. Note Bloom's oblique composition capturing the depth in the shot.

(©2009 Greenpeace.)

Bloom shot some projects with it, including a commercial for Greenpeace (see “Greenpeace: Voices of Change” at http://vimeo.com/6695584; see Figure 10.2). He quickly became one of the foremost gurus of DSLR cinema, even hired by Lucasfilm to show the Lucas team the cinematic potential of the cameras and then later brought on the set of Red Tails (2012) to shoot some plates and pickup shots with Canon DSLRs (see Figure 10.3).

See the following: Philip Bloom's Greenpeace commercial, “Voices of Change” directed by Lucy Campbell-Jackson: http://vimeo.com/6695584; Philip Bloom's timelapse video, “Lucasfilm's Red Tails on set Timelapse”: http://vimeo.com/12148053; Philip Bloom behind the scenes of Red Tails, “Behind the Scenes on Lucasfilm's Red Tails with the Canon DSLRs”: http://vimeo.com/11695817; Philip Bloom's video, “Skywalker Ranch”: http://vimeo.com/8100091.

“When you see them on the big screen, you can understand why Lucasfilm is so amazed by these cameras,” Bloom explains, “and the whole industry is so interested in buying them because filmmaking is an expensive business and a big part of that is cameras and big parts of that [are] the amount of crew that is needed.”

Bloom admits he's not an expert in the design of Canon lenses or the technical aspects of how everything works inside the camera, but he does say, “I'm just very passionate about using them and I use them prolifically and that is why people come to me. They come to me because of my experience.”

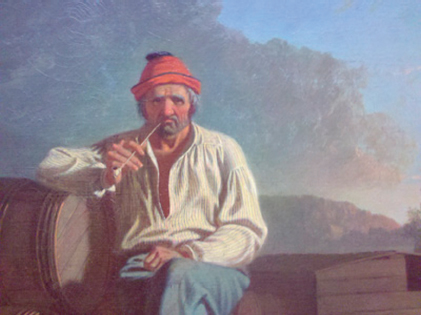

He's distinctly known for a style that captures intimate portraits of people's faces, a style that strikingly echoes with the composition of Bingham's Mississippi Boatman (see Figure 10.3). And for A Day at the Races, the Cooke lenses add compositional strength to Bloom's project.

FIGURE 10.3

George Caleb Bingham's Mississippi Boatman (1850).

Photo of painting by Kurt Lancaster. National Gallery.

But what is more interesting is how some of Philip Bloom's images from A Day at the Races (including many shots from his people series), captures a similar style and composition of Bingham (see Fig. 10.4).

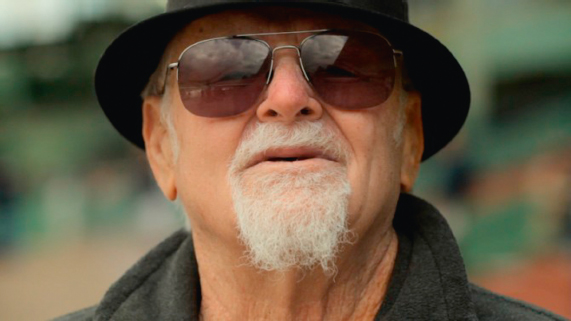

FIGURE 10.4

Philip Bloom captures emotion with a close-up in A Day at the Races.

(©2010 LumaForge, LLC. Used with permission.)

Although I don't believe Bloom has studied Bingham's art, many cinematographers do, and what Bloom instinctively conveys is a keen concept of composition that echoes what a master painter does with composition—all of which provides cinematic strength to his HD videos. Bloom's shots not only convey the compositional sensibilities of an artist (such as Bingham's work from 160 years earlier), but they also engage what good artists always do—capture the essence of humanity in moments of unvarnished truth, the rawness of the human condition filtered through the artist's eyes with aesthetic prowess.

SHOOTING WITH CINEMA LENSES

In early 2010, Neil Smith, founder of the digital post house Hdi RAWworks asked Philip Bloom to come to Los Angeles and shoot A Day at the Races as a proof-of-concept piece—that the Canon 7D can be utilized as a cinema camera by fitting it out with Cooke lenses (S4i; see Figure 10.5). These lenses are meant to be rented, unless you have an extra $20,000 lying around. “As a serious professional post house, the first time I came across HDSLR cameras I totally pooh poohed them,” Smith laughs. “I thought we would never use them. They would never be used in” cinema projects.

Neil Smith hired Philip Bloom not only to shoot a short with a 7D fitted out with Cooke cinema lenses, but to present a master class workshop at The Lot in March 2010. It was a way to prove how these cameras can be utilized by a small crew and still attain a cinema look for film projects. It's a way of “making things simpler and more streamlined. And that's certainly [… what] these cameras are very good at doing,” Bloom says.

FIGURE 10.5

A Canon 7D fitted with a PL mount, sports a $20,000 Cooke lens.

(©2010 LumaForge, LLC. Used with permission.)

Bloom explains how he initially conceived the story with Neil Smith. “He wanted the majesty of the horses through the morning mist running on the race track,” Bloom remembers. But “the longest lens I got was 100 mm” and there was no mist. “Filming horse racing with one camera and the longest lens [at] 100 mm, you aren't going to get much,” Bloom remarks. “I was expecting longer lenses, and I didn't get them, so as soon as I saw the lenses I had, I completely changed the plan. I said, OK, we are going to do the detail behind the racing. We are going to capture the life around the racing instead of the racing itself.”

This became the story—an immersion into the environment surrounding the horse races, such as the stables, rather than the race, itself.

RETROFITTING THE CANON 7D

Hot Rod Cameras (hotrodcameras.com; Illya Friedman, President) designed a PL mount for the 7D, allowing professional cinema makers to mount cinematype lenses, such as the Cooke modeled in A Day at the Races. It's not cheap for low-budget DSLR shooters, but for $3,250, the company will take your 7D and modify it so that it can take the PL mount. For Races, Bloom utilized two Cooke S4 lenses, 25 mm and 100 mm, as well as a modified Tokina 11–16 mm. Bloom loved the way the images with the Cookes turned out. “What a gorgeous image these lenses give you,” he explains on his blog. “Yes it was a lot more fiddly and time consuming using these lenses with a mattebox for NDs than my normal ‘run and gun’ setup but it was worth it. The images … speak for themselves!”1

ON LOCATION

Bloom shot in and around horse stables at Hollywood Park for two and a half hours; then he and his team shot for a couple of hours at Santa Anita racetrack. It was a 5 a.m. shoot. Smith explains, Bloom “shot only in available light. He captured some beautiful images of the race horses being put through their morning training before sunrise and then in the afternoon at an actual race at the Santa Anita track.”

The only shots where they used the mic were with the interviews and the man playing the trumpet. All the ambient noise was recorded in-camera, including the shoveling of the hay (see Figure 10.6). If the level is low enough, editor Jeremy Ian Thomas says, “it's good enough” to use in the project. However, if the levels are too high, “then you hear that kind of tin can feel,” Thomas adds. (Which is why recording on a separate audio recorder is preferable.)

FIGURE 10.6

You can hear the scooping of the hay beneath the music track in A Day at the Races. The audio for this shot was recorded on-camera.

(©2010 LumaForge, LLC. Used with permission.)

Despite the fact they didn't get long lenses for the initial plan of shooting a race, Bloom felt it worked in his favor by covering the backdrop of the races so that they could focus on the people setting up the event, the ones working in the stables. “That is the kind of thing I do anyway,” Bloom explains. “We had the horses in there as background and that worked so much better. I was really happier with it.”

Jeremy Ian Thomas, the editor of the piece, was on location with Bloom, who explained to Thomas that the story “wasn't going to be about the majesty of the horses, but the life swirling around the horses, and that there's this whole other world” where “the horses are actually innocent bystanders in a much more human” story, Thomas says. “It's not really about the horses. They're beautiful and humble and quiet, but around them is a whole industry of gambling, and Philip and I were very cognitive of that early on in the storytelling. He and I were looking at each other like, ‘We need to stay here in the stables.’”

But Neil Smith originally “wanted to go shoot the horses running,” Thomas explains, “but Philip said, ‘Let's stay here’ [in the stables] and I agreed with him. ‘Let's stay here and let's capture the light here, and then we'll move on to the horses.’”

Thomas continues, “Anybody who [watches] it will see that the horses are quite out of focus in a lot of it (see Figure 10.7). They're behind the people, and it's more about the life around it, and I thought that was brilliant.” Thomas pauses. “Horses are great and I think horses are amazing, but there's been a lot of movies and documentaries about horses, but there hasn't been any, that I've seen, about the life around the race horses. And I thought that was pretty cool.”

FIGURE 10.7

A woman poses in front of a horse revealing the shallow depth of field in natural lighting of the Canon 7D in A Day at the Races.

(©2010 LumaForge, LLC. Used with permission.)

Philip Bloom remembers arriving at “the ungodly hour of 4:30 a.m.” They started with Mike Mitchell, a trainer at the Hollywood stables. Bloom remarks on his blog how he has a “family in the racing business in England, and the people working in the stables are generally young blonde students (huge sweeping generalizing there!),” but at the Hollywood stables, “they seemed to be Latin American guys with MASSIVE filmic moustaches. Much more fun for me to film, as people know I tend to film interesting looking people than the obvious pretty ones!”2 And one of Bloom's trademark styles is to gravitate toward the close-ups of these faces (see Figure 10.1).

For most of his previous projects—and all of his personal ones—Bloom typically edits. But due to the time constraints on this project, he passed off the task to Jeremy Ian Thomas of Hdi RAWworks. “It is so nice to see someone else take your work,” Bloom says, “and Jeremy was so tuned in to what I wanted. It worked brilliantly.”

After dumping the footage into the computer, Thomas crosses his fingers and says he “hopes this footage is good”—and he speaks from being one of the people on location that day. “I hope we didn't mess up,” he laughs. He's seen Philip Bloom's work and knows what he's looking for. “I like Philip's editing style,” Thomas says, “but it is different than mine, and I thought, ‘Okay, I don't want to go too far left field and have to re-edit it because he doesn't like it.’ So I kept in mind what Philip might want to see.” But when it came to pacing the film, Thomas took “a lot of liberties.”

Thomas did not want to mimic Bloom's work found in much of his personal short DSLR projects. “His stuff tends to be dissolves—long dissolves, beauty photography of trees and deserts and stuff, and I wanted this to feel more narrative—like it was building and building and building,” Thomas remarks. “I wanted it to feel a little more hypnotic,” while at the same time sticking “pretty close to what [Bloom] was used to seeing.”

Bloom explains how he is drawn to “real people's stories. That's my favorite. I like real people, just telling about their life. Because everybody's got fascinating stories to tell.” Although not in-depth character studies, the stories Bloom creates tend to revolve around people's faces and the environment they're in.

One of the images that stood out to Thomas included a shot “where you see something spinning, and you don't quite know what it is yet, and then the horse comes in frame. I knew that was going [to] be either the opening shot, or one of the opening shots, because I thought it was nice. I liked the abstract feel of that. And then the horse shows up and you go, Oh, okay, it's—and then we go wide, and you see the whole stable” (see Figures 10.8 to 10.10).

FIGURE 10.8

Jeremy Ian Thomas originally conceived this abstract object motion as the opening shot of the film. It appears about 30 seconds into A Day at the Races.

(©2010 LumaForge, LLC. Used with permission.)

Figure 10.9

As the shot proceeds, it goes a bit wide and we see a horse.

(Still from A Day at the Races. ©2010 LumaForge, LLC. Used with permission.)

FIGURE 10.10

A full wide shot reveals the horse tied to an exercise carousel.

(Still from A Day at the Races. ©2010 LumaForge, LLC. Used with permission.)

FIGURE 10.11

Philip Bloom eyes a shot in A Day at the Races on a Marshall monitor attached to the Canon 7D.

(©2010 LumaForge, LLC. Used with permission.)

Thomas explains how he edited in “my mind where I thought shots would go” as he “was watching that [scene] when [Bloom] shot it” (see Figure 10.11). Thomas says that's what he does when he directs a project. “I edit in my mind. When we shoot, I already am piecing it together.”

Thomas feels that color grading is a process that should begin with the cinematographer. “If you're working with a good DP like Philip,” he says, “you're lucky, because you're starting out with a really good color palette to begin with.” Whether DPs realize it or not, Thomas believes they are “being drawn to the color of an image a lot of times, even more than a composition.” In the case of A Day at the Races, what Bloom shot contained “heavy, heavy color tones already,” Thomas observes. “Every image he grabbed had something in it already that I liked” as a colorist. “So I would either enhance what was already there, or I would dial it back if there was too much of it. Some of the stuff inside the stalls was too yellow, so I would have to dial the yellow back and bring some more earth tones beneath the yellow” (see Figure 10.12).

FIGURE 10.12

A shot from inside a stable, which for Jeremy Ian Thomas was too yellow, so he, as the colorist, “would have to dial the yellow back and bring some more earth tones beneath the yellow,” he explains.

(Still from A Day at the Races. ©2010 LumaForge, LLC. Used with permission.)

But this process isn't always easy, especially with some other DPs who are not looking at colors. “When you're not working with someone like Philip, and there's not a lot of color, you have to really make the DP look good, [as if] he saw that color already,” Thomas explains. “But all I really did with A Day at the Races was keep the skin tones intact by doing a desaturation of the skin tones, and then I would saturate everything around the subject, because the colors were already so beautiful. There were these really nice greens, mid-level greens, and there were these really beautiful pink hues across the mid-tones at the stables. And there was a nice yellow, and some pink.” When he saw a person in a shot, Thomas said he “would make sure their skin tones were right. But everything around them was popping, and colorful” (see Figure 10.13). Overall, he felt that it was “a really good grading experience.”

In the end, Bloom was happy with the project. He gave some notes to Thomas after seeing the rough cut, and additional changes were made. Bloom wouldn't have chosen the particular piece of music for the piece and would have taken a different approach for the final edit, he explains, but he admits that “it's always great to see how someone else interprets your work.”

Bloom also enjoyed using the Cooke lenses on the 7D, but at the same, “I honestly feel for the type of shooting that I do, like this piece, that using Canon or Zeiss lenses would have been just as great.”

FIGURE 10.13

The colors would “pop,” as Jeremy Ian Thomas explains in observing A Day at the Races. He would make sure the skin tones were correct and then bring out the colors by saturating them a bit.

(©2010 LumaForge, LLC. Used with permission.)

Neil Smith was pleased with the work that Bloom and Thomas did: “When we screen the movie in our theater,” Smith boasts, “people are truly amazed at what Philip was able to capture with the low-light capability of the 7D and with a documentary style of shooting.” In short, Smith explains, “the real purpose behind the film was to show how HDSLR cameras can be used to help creative filmmakers tell their stories, easily and cheaply without sacrificing production value.”3

1 http://philipbloom.co.uk/2010/03/04/shooting-7d-pl-with-cooke-lenses-for-saturdays-la-masterclass/, accessed 26.04.2010.

2 http://philipbloom.co.uk/2010/03/04/shooting-7d-pl-with-cooke-lenses-for-saturdays-la-masterclass/, accessed 26.04.2010.

3Cheap in relationship to the cost of a cinema film camera, as well as film stock. The lenses, however, are not cheap, but this film shows that a modified Canon 7D can utilize a high-end lens package that can be rented without having to use a full-size cinema camera.