RECORD SOUND LIKE A FILMMAKER

The cinema law of sound: No one can watch a film if the audio sounds bad. No matter how good the image, poor audio quality will block your viewers from ever appreciating the image. Do not ever skimp on sound. It is the most important element in scenes with dialog. In fact, you can present a fairly poor image and if the audio is spot on, people will enjoy the movie—more so than good images accompanied by bad sound. Bad sound is a dead giveaway that the film was made by an amateur.

With DSLR cameras, it's pretty easy to get bad sound. But with some basic knowledge and the proper tools, the DSLR shooter can record great audio. Most of the large sensor video cameras contain XLR inputs, where filmmakers can plug in audio with professional connections—just don't use the built-in microphones of any video camera or DSLR. Dialog should never be recorded with the built-in camera mics—ever. Jared Abrams (WideOpenCamera.com), says he likes the fact that DSLRs make you go “back to basics” of filmmaking:

The way they started motion picture was one frame at a time. And eventually they just strung ‘em together until it looked like something they were used to and liked, and off we went. The DSLR cameras are doing just the same thing. It's a great sync-sound camera. If you treat it like that, then you'll get the most out of it. If you run separate sound, you will get better sound. And the fact that they didn't jam all this audio into it just makes it a more potent camera. That's one of the bad things about standard little video cameras is that they're trying to jam all this audio technology into it.

(Interview with author, March 2010.)

Whether you're shooting with a DSLR or a large sensor video camera with XLR inputs1 the best sound will always come from an external recorder with a field mixer. This is what professional filmmakers do anyway. And DSLRs, when treated like a film camera needing external audio, allows the camera to be excellent at recording video. Because DSLR manufacturers decided to deliver a strong picture over strong audio—and there's a compromise on space—DSLR shooters must shoot like filmmakers when recording sound. Ideally, recording sound separately, or at the very least, disabling the automatic gain control (AGC) in the camera, getting the proper microphones, and connecting the mic to a professional audio adapter (containing a preamp with limiters) are essential in getting the best possible sound.

This chapter defines sound quality, provides terminology for different microphone types, the different audio gear you can get, how to use Magic Lantern to get incamera monitoring of audio on some Canon DSLRs, and a case-study on capturing “run-and-gun” audio with a 5D Mark II.

The following are some basics you, as the filmmaker, should consider when recording audio for your projects:

DSLR shooters must shoot like filmmakers when recording sound.

The answers to these questions will determine your audio quality. This chapter covers these topics so you can be more informed in your choices as you shoot and know the impact of compromises. You should test through postproduction and into a final export of your project to understand what your final field audio recording will sound like.

Sound Quality

Just as the cinematographer must be aware of the quality and source of light in a scene, filmmakers need to be aware of the ambient room quality. Is it hard or soft? Hard walls and hard floors will reverb your audio, providing micro-echoes of sound in the space. Test the sound quality by yelling in the space. If you hear an echo, reverb will be abundant and the audio may sound a bit tinny. A room with carpeting, furniture, and so forth will absorb the sound and break up the audio wavelengths, so the reverb will be minimized. Outdoors (other than an alley, for example) will likely provide a soft sound quality. A windy day will cause audio impacts, pretty much ruining the recording. Using a windscreen will minimize this damage—not the foam windscreen that usually comes with the mic, but a large, thick, furry screen covering a sound blimp for wind production (such as the one depicted in Figure 5.8).

In addition, the filmmaker must decide if the subjects should sound close or far away. In most cases, their voices should sound as though they're close, so the microphone must be brought in close (less than three feet or closer). If distance needs to be conveyed, then pull the microphone back so it sounds as though someone is talking across the room, for example.

In addition, many DSLR cameras utilize automatic gain control, which means the camera will adjust the levels of the audio coming into the recording, depending on how much sound is hitting the mic. A lot of sound will lower the input, whereas soft sounds will force the camera to increase the levels, typically causing unwanted hiss. In either case, the AGC will result in bad sound by recording uneven audio levels and adding extra noise when the levels are low and the AGC increases to compensate. In most cases, you want to turn off the AGC, which is really not an option for most DSLR cameras. The Canon 5D Mark II and III, Canon 60D, and the Rebel T3i allow for manual control of the audio. BeachTek and juicedLink are two companies that provide devices to disable the AGC of cameras and allow you to input XLR microphones (more about them later in the chapter). These devices trick the camera so that it thinks all the audio is even, allowing manual control of the audio. In addition, the firmware hack Magic Lantern will remove AGC as well (but not in the Rebel T3i or 7D).

Furthermore, audio is recorded at different qualities. A 44.1 kHz, 16-bit recording is lower quality than a 48 kHz, 24-bit recording. The first number refers to the sampling rate—the amount of times per second the audio is sampled (44,100/second), and the second number refers to the amount of information recorded per sample (16 or 24). If you're using an external recorder, you have the option of setting different compression schemes. Just make sure you set the same compression as the camera so you can sync them up in post. Do not use compressed mp3 recording—no matter how high the bit rate. Keep your audio data as raw as possible!

Also, when recording audio, such as dialog, be sure to record room tone in every space you record. Have everyone on set be quiet and record blank audio for at least a minute. This will capture the ambient sound you will need in editing in order to fill in gaps between takes or to even out the sound quality from different takes.

Checklist for Sound Quality

| 1. | Are you indoors or outdoors? |

| 2. | What is the surface quality of the environment? Will the sound reverb, or is it absorbed in the environment? If you're getting a lot of reverb, get the microphone in really close. |

| 3. | Do you want your subject to sound close? |

| 4. | Do you want your subject to sound far away? |

| 5. | Can you turn off the automatic gain control? If not, then use an audio adapter (or Magic Lantern on some Canon DSLRs) that turns it off or use an external digital audio recorder. |

| 6. | What is your compression value? (You don't need this unless you're using an external device.) |

The following sections provide an overview of some of the equipment you may think about using on your shoots. They include a justification of what works well and why. Some of this information may be a review for experienced filmmakers, so feel free to skip over it. If you're relatively new to filmmaking, the information may be useful, especially if you're trying to get better sound for your projects. The final section of the chapter will walk you through two audio workflow setups covering the recording of an external onboard mic and an external digital recorder with the intention of syncing your audio (covered in Chapter 6 on postproduction workflow).

Microphone Types

Microphone types sound differently; they will convey distinctive audio qualities depending on the space you're in. The major mic types include lavalieres (lavs), omnidirectionals (omnis), cardioids, and shotguns. They will never sound the same.

![]() Lavs are needed for wide shots with dialog (we'll see the boom pole with a shotgun mic in a wide shot).

Lavs are needed for wide shots with dialog (we'll see the boom pole with a shotgun mic in a wide shot).

![]() Cardioids are for use indoors.

Cardioids are for use indoors.

![]() Shotguns are for outdoor medium and close-up shots.

Shotguns are for outdoor medium and close-up shots.

Cardioids provide the best sound recording but pick up too much noise outside. Because shotgun mics have the rear lobe pickup pattern, they'll pick up reflections of sound off the ceiling and wall, resulting in interference when shooting indoors. Lavs, although useful for picking up dialog in a wide shot, don't sound as good and need to be postprocessed to bring back the warmth of a person's voice. For run-and-gun journalists and documentary filmmakers, the shotgun is the best choice if you can choose only one mic.

Many of these mics include space for a battery, but you will want to use phantom power if available because it will increase the quality during recording, although it will reduce the battery life of your recorder. The voltage allows the signal to be picked up when sound waves hit the front plate, changing the value of the air quality against a capacitor and turning it into an electric signal. On the other hand, dynamic microphones—the ones you see reporters use on television news—are more rugged and do not require any external power. But the sound quality is not as good as condenser microphones.

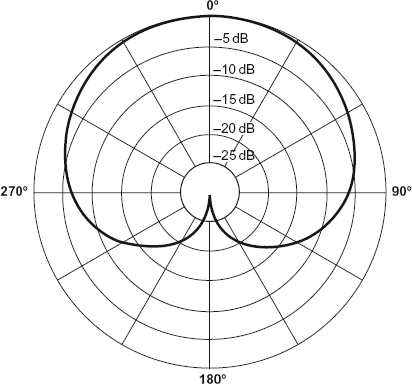

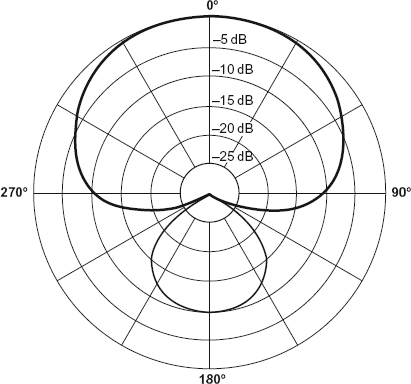

Shotgun microphones are unidirectional, oftentimes with a cardioid or super-cardioid pickup pattern. A cardioid pattern allows you to record sounds from the direction the microphone is pointed (see Figure 5.1), whereas a supercardioid—found in shotgun mics—does the same thing but also picks up some sound from the rear (see Figure 5.2).

FIGURE 5.1

Cardioid pickup pattern. (The Microphone, your voice's Gateway to the World. Voiceover4us.com. <http://www.voiceover4us.com/blog/2008/07/15/14/>, accessed February 2, 2010.)

FIGURE 5.2

Super cardioid pickup pattern. Typically found in shotgun mics. (The Microphone, your voice's Gateway to the World. Voiceover4us.com. <http://www.voiceover4us.com/blog/2008/07/15/14/>, accessed February 2, 2010.)

FIGURE 5.3

Rode VideoMic Pro with foam cover. This mic includes a built-in shock mount to reduce noise from movement. The foam windscreen is not useful against wind; you'll need a wind muff that's designed for this mic. The frequency response of this mic ranges from 40 Hz to 20 kHz. This mic uses a minijack connector; it's a high impedance mic but can connect directly to the DSLR's microphone jack without any kind of adapter. This minijack mic could be plugged directly into an external audio recorder. You may want to tape the minijack plug so that there's less of a chance of having the cord accidentally being pulled during a recording.

(Image courtesy of Rode.)

One of the popular mics that can be attached to the DSLR's accessory shoe is the Rode VideoMic Pro (see Figure 5.3), a light shotgun mic that attaches on top of the DSLR (see Figure 5.4 for a polar pickup pattern chart for this mic). If you're traveling light and shooting a news piece, documentary, or a wedding solo (without anyone helping out with sound), then this is probably one of the most useful mics you can get for your DSLR. It will not be as good as a shotgun mic with an XLR adapter, but it will provide usable sound for your production.

The Rode VideoMic Pro will provide usable sound for run-and-gun style documentary and journalism work, but it's recommended that it be used to record decent reference audio and as a backup source in case your audio recorder fails. It is better to use a higher-end mic with an XLR adapter, especially if you're submitting for broadcast or to a film festival, where audio really matters.

If you're shooting solo and going for speed, attaching an on-camera mic, such as the Rode VideoMic Pro, is a great choice. When you're talking to someone, be sure that person is close, no more than three feet away, if you want to capture as clean a sound as possible. This may work great for news and documentary. However, when shooting short fiction pieces and commercials, you will want wider shots and still pick up clean audio. But because the performers are more than a few feet away (even five feet is too far), you'll need to run longer cable. Be aware that microphones with minijack plugs (the standard tip-ring-sleeve, or TRS, connectors) are high impedance using unbalanced cables and the signal will weaken over distance, and these mics are prone to picking up noise and interference (such as a radio station). It's best to use a balanced cable (XLR).

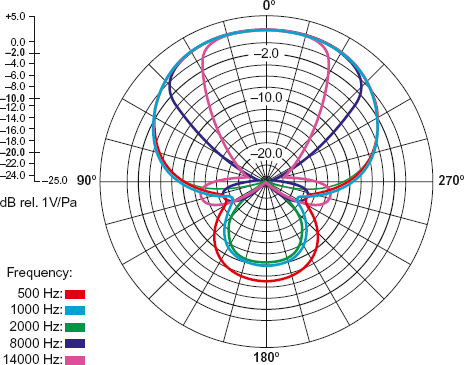

FIGURE 5.4

Rode VideoMic Pro's polar pickup pattern measured in frequency response. The Hertz refers to the wavelength. The lower number is low-frequency sounds such as rumbles and bass. The higher frequency expresses higher tones. A human voice can range from 80 Hz to 1100 Hz.

(Image courtesy of Rode.)

The Rode NTG-2 shotgun mic is a decent dialog microphone, most useful for outdoor shots or indoors if sound reflection is minimal (see Figure 5.5), and if you're shooting solo, attach this mic to a DSLR rig along with an XLR adapter that provides phantom power, and you'll get really good sound. If you have a sound person, this type of mic is a great choice when attaching it to an external recorder (such as a Tascam DR-40 or Zoom H4n).

Whatever shotgun mic you end up using, knowing its strengths and weaknesses is important. Note, for example, the frequency response of the Rode VideoMic Pro compared to the Rode NTG-2. The NTG-2 can go as low as 20 Hz, whereas the VideoMic Pro is limited to 40 Hz. Fewer low frequencies will be picked up by the VideoMic Pro. However, often a boom pole sound operator will engage the low-cut filter to minimize boom pole handling, removing the lower frequencies from the shotgun mic.

Shotgun mics provide the best sound in your recording work, but using a shotgun inside a room with a lot of reverb will cause extra audio muddiness.

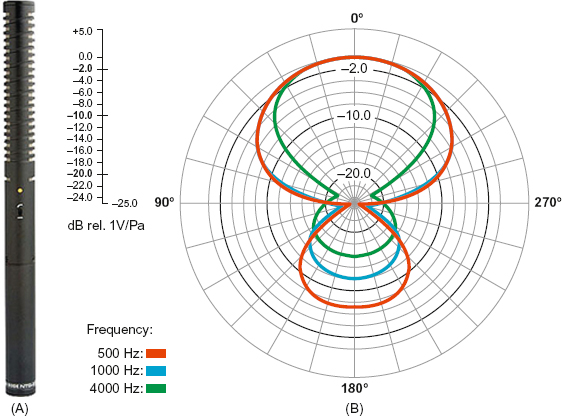

FIGURE 5.5 A AND B

The Rode NTG-2 shotgun microphone and its polar pickup pattern. A good budget dialog mic. The frequency response of this mic ranges from 20 Hz to 20 kHz. This mic uses an XLR connector, which means you'll need to use an audio adapter from BeachTek or juicedLink.

(Image courtesy of Rode.)

If, instead, you use a mic with an XLR connector (with balanced cable, which will resist the noise that high-impedance lines will pick up), you will have the advantage of running long cable, and it'll pick up very little to no noise, and the audio quality will stay high. Interference will be minimized. But you will need to hook it up to an XLR adapter if shooting with a DSLR or use an external audio recorder with XLR inputs, because DSLR cameras currently available do not contain XLR inputs (see the “XLR Adapters” section later).

It must be noted that the interference tube in shotgun mics doesn't work well indoors—unless there's a lot of sound absorption material, such as furniture. Sound reflecting off the wall skews the frequency and draws attention to the echo sounds. If all you have is a shotgun mic, typical of run-and-gun style doc shooters, video journalists, and indies, be aware of the space you're in and adjust the direction of the mic, as needed. Holding the mic from below, for example, may minimize sounds bouncing off the walls.

When pointing a shotgun mic at someone, remember that it will pick up sound behind the person, so if she is standing on a sidewalk and you're facing the street with the camera-mic setup, you'll get loud traffic noise. If you have the person turn around so you're facing a storefront, you'll get much cleaner sound. When shooting a documentary in Hood River, Oregon, I interviewed many people on the street asking them about their Sasquatch sightings. The shotgun mic was held close to them, and traffic noise was minimal, despite the number of cars and trucks rumbling by. In addition, holding the mic up in the air (with a boom pole or pistol grip) and pointing down toward your performer's voice will also minimize external sounds because extra noise is minimal when pointing toward the ground.

FIGURE 5.6

Sennheiser's wireless lav G3 microphone system. It's expensive at $600, but the wireless will give you a lot of flexibility on shoots.

(Image courtesy of Rode.)

Most lavaliere mics are omnidirectional, picking up sound from all directions. If you want someone to sound close up and personal, the lav mic, when wired properly, provides good, clean sound. Lavs require a transmitter box that typically hooks to the subject's belt, and a wire attached to the mic is strung up beneath the subject's shirt and hooks onto the shirt collar (see Figure 5.6). An XLR wire connects the transmitter box to the camera's XLR adapter. There are also wireless models, which allow the transmitter to send the audio remotely to a receiver that connects to the XLR adapter.

Built-in mics, no matter the camera, are nearly useless and usually provide poor sound quality. They're useful only for reference audio if you're recording sound externally on a digital recording device. If you must use the onboard mic, make sure it's not windy and make sure your subject is standing less than three feet away.

For DSLR cameras, phantom power is provided only with onboard external XLR adapters or external digital recorders.

Getting the Right Mic and Using a Boom Operator

Filmmaker David Anselmi says that “even a crappy mic sounds better on a boom! A mic with a boom pole and a good boom operator can give you great sound—much, much better than a $1,000 Sennheiser 416 mounted on the camera!”

In addition, Anselmi recommends going for microphones in the $600-$1,000 range. “You may want to do an A/B comparison of a lower-end mic with a high-end mic with excellent audio monitors, so you can hear the difference—you'll never be satisfied with a $250 mic again. Also, for outdoors—especially in heavy wind—a blimp is essential.” Words of wisdom as you shop for the right microphone. Testing is always the best rule of thumb. If you're in New York City, B&H Photo has an audio room where you can test microphones (other professional video/audio gear stores will also allow you to test microphones).

Windscreens

Windscreens are absolutely essential when shooting outdoors, even if there's only a light breeze. Wind impacts a microphone's diaphragm hard and can easily damage your audio. The foam covers that come with microphones are really designed to soften the speech of the performer; they're not windscreens and will not hold up to outdoor use even on a light windy day. Rather, using a wind muff or windscreen is the way to go when there is a breeze (see Figure 5.7). They slip over the microphone, and their thick, furry cover breaks up the impact of light breezes. Some models cover the microphone snuggly; others, such as Rycote's Miniscreen, leave a gap between the mic and windscreen, which, from my tests, seems to work better in stronger wind (see Figure 5.8).

FIGURE 5.7

The Rycote Softie offers some protection against wind but is not good for moderate levels of wind.

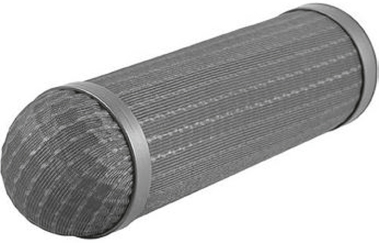

FIGURE 5.8

Rycote's Miniscreen is a great budget option (~$80) for taking out moderate wind noise on a shotgun microphone.

XLR Adapters

If you want to get good sound out of a DSLR, utilizing a preamp with XLR connectors is one of the best options if you're not using an external recorder. You'll get a rich and clean signal. This option also allows you to use professional XLR microphones.

Furthermore, using an XLR cable is a must for recording over a distance of a few feet, and because DSLR cameras do not contain XLR inputs, you'll need to use an XLR adapter. JuicedLink and BeachTek are two popular companies that build XLR adapters. The two products I'll describe here also allow for audio monitoring (with headphone inputs), provide phantom power for microphones, and subvert the automatic gain control of the audio in-camera. As noted before, most, if not all, DSLR cameras use AGC; the only exceptions as of this writing are the Canon 60D, 5D Mark II and III, Rebel T3i and the 7D.

Be sure the adapter has the proper transformer and circuits; otherwise, the noise resistance natural to the XLR cable will be lost. In addition, the XLR adaptor box contains a mini-jack that plugs into the DSLR's mic input; this input can easily break. Some people hot glue the right angle connector into the minijack and cable-tie the slack to the camera, connecting and disconnecting the cable from the adapter box.

BEACHTEK DXA-SLR XLR ADAPTER

BeachTek's DXA-SLR model includes a microphone preamp (15 dB) to help provide a clean signal for your microphone (see Figure 5.9). It's designed so you can access the battery of the Canon 5D Mark II. It also has 48 volts of phantom power, which is an added bonus for powering your mics. It doesn't have LED meters for monitoring audio input levels, but it uses a single LED to indicate red when audio clips.

FIGURE 5.9

BeachTek's DXA-SLR model.

(Image courtesy of BeachTek.)

JUICEDLINK'S PREAMP DT454

JuicedLink's preamp DT454 provides clean audio with the circuitry of its preamp—a product designed for video cameras needing XLR adapters (see Figure 5.10). It overrides the automatic gain control of DSLR cameras with an AGC disabler not needed for the Canon 5D, 60D, and Rebel T3i. It allows you to use up to two XLR mics, as well as two minijack unbalanced mics (useful for those who own Rode's VideoMic Pro but want a clean connection and clean sound). It also includes LED level meters, a headphone jack (a must-have!), as well as 48 V and 12 V of phantom power.

FIGURE 5.10

JuicedLink's preamp DT454.

(Image courtesy of JuicedLink

Pistol Grip and Boom Pole

Pistol grips and boom poles are basic tools if you're working with a crew. If you're running and gunning, then stick with your onboard external microphone, but if you have at least one other person helping out on the shoot, use a boom pole to bring your mic in close to your subject. A pistol grip provides a similar tool for medium and close-up shots (see Figure 5.11). I've sat in a chair during an interview and handheld the mic with a pistol grip, just out of frame, and received excellent quality sound because I can place the mic a foot or two closer to the subject than just placing it on-camera. In this kind of setup, I put the camera on a tripod, use an external audio recorder, and sit beside the camera so I can monitor the image during the interview. When using a boom pole, be sure to strap the cord to the pole, so the wire doesn't hit the pole, creating additional noise.

FIGURE 5.11

A Rycote pistol grip. Great for getting a mic in close when you have tighter shots. The device is designed to minimize noise when holding a shotgun microphone.

(Image courtesy of Rycote.)

External Recorders

If you want to get good clean audio with DSLR or large sensor video cameras, the Zoom H4n (~$300) (see Figure 5.12) and Tascam DR-40 (~$200) (see Figure 5.13) are two possible choices for you to record sound separately, while getting a professionally clean recording with XLR mics. For a bit more money, Tascam's DR-100mkii (~$330) is their update for their quality DR-100 model. They record digitally onto an SDHC card.

FIGURE 5.12

Zoom H4n audio recorder.

(Image courtesy of Tascam.)

Essentially, these recorders allow you to hook up a professional microphone to their XLR inputs, so you'll get the clean audio. There are also a variety of settings that can be chosen, but be sure to pick a non-MP3 compressed format. Use 44.1 kHz, 16-bit or 48 kHz, 24-bit (or the one that matches the audio compression of the camera—if it's a different rate, you may get material out of sync). You will still record audio on the camera's microphone and use it as a reference, and replace it with the clean audio after you've synced it up using a lip sync software, such DualEyes, a standalone application for PC or Mac. (Final Cut Pro X has a synchronization feature built into the software.) As a back-up (in case you have to do a manual sync) record a slapping of hands or use a slate at the beginning of the take, and make sure everything's recording; it's sometimes too easy to forget to turn on the external recorder!

FIGURE 5.13

Tascam DR-40 audio recorder.

(Image courtesy of Tascam.)

Use the Rode VideoMic Pro connected to the DSLR's hotshoe as your reference and backup sound (or hook up a shotgun mic to your video camera; then bring in the XLR mic as close as possible. You could consider putting the device on a small tripod. If you're using only a minijack microphone, you may want to consider getting the Marantz PMD620 audio recorder. It doesn't have XLR inputs, but it'll give you a clean recording—much better than the on-camera mic.

If you do not want to deal with an external recorder and you want the best possible sound out of any video camera or DSLR, you may want to consider a more expensive option (~$750): Sound Devices MixPre-D (see Figure 5.14). It's a portable field mixer and mic preamp that contains unclippable limiters, so, if set properly, it will not blow out any sound. It's made of metal, so the rugged device will hold up to some impact abuse. If you're utilizing this with a DSLR, the MixPre-D includes a locking connector to the DSLR, feeding the field mixer's clean audio to the camera. The chief advantage is the ability to use XLR microphones, but you can also monitor audio, engage phantom power for mics, adjust the levels, and view an LED level meter. Hooking this up to an audio recorder (such as the Tascam DR-40) will provide pristine sound.

Without such limiters found in the MixPre-D, you'll want to record your audio at 212 dBu or 220 dBu to minimize the risk of clipping audio if a subject or performer gets too loud. However, the audio levels will be low and will have to be boosted in post (usually the normalization gain). When you're boosting, the audio will usually result in increased noise, so you may need to use a noise reduction plug-in for the software. With an optional plate, this device can be attached to the tripod connector of the camera.

External Microphone Audio Recorder

The Rode VideoMic H D (see Fig 5.15) contains not only a modified NTG-3 condenser shotgun microphone and a metal casing mini-blimp (for wind protection), but also a built-in audio recorder—all of which mounts on the shoe adapter of the camera. In addition, it also includes a minijack microphone input, a line input, a headphone jack (most DSLRs don't include them) with a headphone amplifier, a level meter, among other features.

FIGURE 5.14

Sound Devices MixPre-D is a powerful preamp for adding quality audio to your recordings. Clean and quiet preamps with unclippable limiters make this one of the most powerful tools in your audio arsenal. It includes a DSLR feature that allows you to input this device directly to the camera's unbalanced (high impedance) microphone input.

Headphones

You need to monitor the audio when shooting. The problem with most, if not all, DSLRs is their lack of a headphone jack—thus, the importance of getting an XLR adapter with a headphone input or using an external digital audio recorder. Monitoring sound will allow you to know when something's not working right. Unfortunately, without a headphone jack on the DSLR and monitoring only through the XLR adapter, you don't know if something is going bad with the sound in-camera. This is another reason why using external recorders for DSLRs is important.

With that said, there are headphones designed to sound pretty, and then there are headphones designed to sound accurate: monitor headphones. You want the headphones that sound accurate. One of the best websites detailing unbiased ratings and sales of headphones is <http://headphone.com>. For studio use—mics that will sound accurate—this site recommends four models for ~$100 and under (two of which are at ~$60): Beyerdynamic DT2325 (~$60) and Shure SRH240 (~$60 see Figure 5.15); and Sennheiser HD 280Pro and Shure SRH440 (at ~$100). Go to their site and scroll down to “Headphones for Studio Use”: <http://www.head-phone.com/selection-guide/dj-and-studio.php>. Sony also makes a monitoring headphone that is good for field production: the MDR-7506 (~$90).

FIGURE 5.15

Rode's VideoMic H D contains not only a high-end microphone based on their NTG-3 mic, but an audio recorder, as well as a headphone jack, useful for DSLR shooters.

(Image courtesy of Rode.)

Getting the right headphones—within the parameter of making sure they're designed for monitoring sound (studio and/or field production)—is essential. But once you have the choice paired down to headphones that are designed for accurate monitoring, the ones you purchase should be those that are comfortable for you to wear.

Magic Lantern for Canon DSLRs

The Magic Lantern firmware hack (instructions and software located here: <http://magiclantern.wikia.com/wiki/Unified>) that temporarily updates the camera's firmware booted from the camera's memory card, adding such video camera features as audio meters, headphone monitoring, spot meter, histogram, among other functions on most Canon DSLRs. It is free, but it does not work on the 7D and the audio capabilities don't work on the Rebel T3i 600D, but it works with the Canon 5D Mark II, 600D, and Rebel T2i (550D). Installing Magic Lantern does void your warranty, and it is not supported by Canon, and this author only recommends it for experienced shooters (he and Focal Press make no warranties or guarantees for your camera). You proceed at your own risk.

Magic Lantern includes disabling of the automatic gain control (AGC) for audio (useful for those shooting with a Rebel T2i 550D—which is absolutely key when you want to even attempt to get usable audio in your footage. Furthermore, it puts the audio bars on the LCD screen so you can see what the audio is doing. Sescom makes a cable that plugs into the AV port of the camera and converts it to a headphones jack. (The Rebel T2i/550D and 60D cable is located here: <http://www.sescom.com/product.asp?item=DSLR-550D-HOCF>; the 5D Mark II cable is located here: <http://www.sescom.com/product.asp?item=DSLR-5DMKII-HOCF>.)

Furthermore, it contains a focus assist tool that lights up the focus plane with blue pixels, so you don't have to wonder if you're close on the focus—you know you're there (the feature doesn't work well in low light, however). You can even dial in color temperature on the Rebel T2i (550D), which is a feature already in most of the other Canon cameras.

I have installed it on a Rebel T2i, a 60D, and my personal 5D Mark II and never had a problem with it. Another feature includes the focal length of a zoom lens, as well as the focal plane distance, so focus can be pulled more precisely and helps with marking tape. (See Figure 5.16.)

FIGURE 5.16

Magic Lantern Unified on a Canon 60D. Along the top, we can see the audio meters that change color (green for within the zone, yellow getting hot, red for clipping). It shows the remaining space on the memory card (11.8 GB). The spot meter in the center places the exposure at 34%. While the histogram hovers above center to the right. Along the bottom can be seen the size of the lens and the f-stop setting (50 mm at f/1.8), the shutter speed 1/41, the ISO (400), and the color temperature preset (Sunny).

(Photo by Kurt Lancaster.)

The installation instructions are located here:

<http://magiclantern.wikia.com/wiki/Unified/install>.

The user guide instructions is located here:

<http://magiclantern.wikia.com/wiki/Unified/UserGuide>.

Here's my short guide for installation (again, I take no responsibility for failed installs and damage to your camera. Proceed at your own risk.):

| 1. | Be sure the camera has the latest firmware release (as of this writing, it's 1.0.9 for the Rebel T2i (550D). Be sure to read the site's latest updates (in some cases, you may need to roll back a Canon update in order to have Magic Lantern work). If not, then go to Canon's website and scroll to the bottom of this page and hit “I agree”: <http://web.canon.jp/imaging/eosd/firm-e/eosdigital7/firmware.html>. You'll be taken to another page where you can download the firmware. Place the file on your memory card and put it back into the camera. Put the camera in manual mode, then index finger dial over to the third toolbar menu. Go to firmware and click on it to update. Be sure your battery is fully charged. (A battery dying during the install can be very bad.) |

| 2. | After updating, plug in your camera's memory card to your computer and delete Canon's 1.0.9 firmware from the card. |

| 3. | Download the firmware from this page: (as of this writing, the latest version is dated December 22, 2011), <http://magiclantern.wikia.com/wiki/Release_2011Dec22%20and%20unzip%20it.> |

| 4. | Copy all of the Magic Lantern files to the card (don't place it in any folders). |

| 5. | Put the memory card back into the camera. |

| 6. | Update the Magic Lantern firmware as if you're doing step 1: Put the camera in manual mode on the top dial and dial over to the third toolbar menu. Go to firmware and click on it to update. It'll tell you when it has updated successfully. |

| 7. | Pull out the battery for about 10 seconds and turn the camera off. |

| 8. | Dial the camera to video mode. Turn on the camera and hit the delete button to bring up the menu. |

| 9. | The camera will use Magic Lantern with this card. If you want to use it on other cards, then you will need to install the same files. If you format that card, you'll be given the option to keep Magic Lantern on the card, otherwise you'll have to reinstall it. |

| 10. | Read the User's Guide to see what each function does. |

My Magic Lantern menu settings (default unless otherwise noted; read the manual for an explanation of the all the settings):

Audio

Audio Gain: This is where you adjust the levels. Mine is currently at 23 dB.

Input Source: You can adjust to include external and internal at the same or choose “external stereo” (which is what I normally do).

Output volume: Sets headphone levels. I've set mine to the maximum of 6 dB.

Audio Meters: ON.

LiveV (I keep everything off, except the following:) Global Draw: ON Focus

Peak: D1xy, 1.0, local (Aside from the audio settings, this is the key reason I use Magic Lantern--the ability to know where you are in focus.) Spotmeter: Percent, AFF

Waveform: Small (sometimes I'll use this over the histogram).

Movie

Movie Restart: ON (When the camera hits the 4GB file size limit around 12 minutes, instead of the recording shutting off, it'll turn itself back on, so you'll only lose about a second.)

I don't adjust any of the other menu settings.

Magic Lantern Case Study—Occupy Wall Street with the Canon 5D Mark II

When shooting on the run, it's important to travel light. I was in New York City on other business in October 2011, when I decided stop on by Zuccotti Park and observe Occupy Wall Street. I brought my Canon 5D Mark II with two Zeiss Contax 50 mm f/1.4 and 35 mm f/2.8 lenses with a Lightcraft ND fader, a Sennheiser ME62/K6 omni-directional condenser microphone (it is a great dialogue mic and short), a Lightwave windscreen, a special XLR to minijack connector (made by ETS), a Sescom AV headphone cable, and headphones. I had one spare battery and two 16 GB memory cards. (See video at: <http://vimeo.com/30500114>.)

Pulling out my gear, I noticed many others using larger video cameras, but with my low-profile setup, I had easy access to many different subjects. I handheld all of the shots (with no rig attached to the camera). I kept the camera close to the subjects (in most cases three feet or less) so as to get their audio clear on my mic as possible (see Figure 5.17). Although I wished I had brought along my shotgun mic, I couldn't find the right windscreen, so I kept with the low profile mic, because I had a windscreen, and I felt that was more important than getting the directional sound of a shotgun mic.

I attached the Sennheiser mic to the shoe mount using a shockmount, and plugged it directly into the mic input of the 5D using the new XLR to minijack camera balun (the ETS PA910) series, providing a low to high impedance connection to the camera. (See Figure 5.18.) In other words, in a pinch, it'll provide decent audio when you don't have a separate digital audio recorder on hand (such as the Tascam DR-40). However, I would not have done the shoot without using Magic Lantern, so I could see audio meters while recording

and monitoring the audio by plugging into the AV port of the 5D. Indeed, I adjusted the audio several times based on the levels I watched.

FIGURE 5.17

By keeping the camera close to the subject (2.5’-3’) at Occupy Wall Street in New York City, I was able to record decent audio with a Sennheiser ME62/K6 attached to a 5D Mark II with a shockmount and a XLR to minijack step down cable. Lens: Zeiss Contax 50 mm f/1.4. The open aperture provided a nice shallow depth of field for the interview shots, which allows for the audience to focus on what the subject is saying, while the wider lens was used for deep focus scenic shots. (Lancaster, K. and Sotosky, S. (2011). Occupy Wall Street—New York City. Vimeo. com. <http://vimeo.com/30500114>).

(©2011 Kurt Lancaster)

FIGURE 5.18

Light run and gun setup for Occupy Wall Street. The setup included a Canon 5D Mark II and a Zeiss Contax 50 mm f/1.4 lens along with a shockmount holding a Sennheiser microphone attached to the camera, and the ETS step down cable (XLR to minijack), as well as a headphone adapter by Sescom providing the ability to use headphones when Magic Lantern is installed.

(Photo by Kurt Lancaster.)

I shot the project handheld with no strap, no DSLR rig. The omnidirectional aspect of the ME62 picked up a lot of side and background noise, but it ended up adding to the atmosphere of the piece. Furthermore, I stood close to the subject, so the microphone was less then three feet away. I shifted my head to the left, while hand-holding the camera, so the subject being interviewed would look at me and not the camera. The project was edited by my friend, Stacey Sotosky.

This was my test whether the step-down cable with a high quality mic could record usable audio. It did. At the same time, Magic Lantern's capabilities for audio monitoring allowed me to treat the project as if I were using a video camera—but with the benefits of the cinematic quality of a Canon 5D Mark II.

Checklist for External Onboard Minijack Mic

| 1. | Choose your microphone (such as the Rode VideoMic Pro or a shotgun mic with an XLR to minijack step-down cable if shooting with a DSLR), attach it to the accessory shoe plate, and plug the mic directly to the microphone jack of the camera. |

| 2. | Turn on the mic (be sure you put a fresh battery into the microphone). |

| 3. | If possible, turn off the AGC and set the audio input levels of the camera at 212 dBu to minimize clipped audio (keep the levels under –6 on the meter). |

| 4. | Keep your subject no more than a few feet away or so; this will provide the strongest audio signal. |

| 5. | Monitor with headphones and adjust levels as needed. If you're shooting with a DSLR with no audio monitoring capabilities, consider installing Magic Lantern. |

| 6. | Input your files normally. The audio is recorded simultaneously with the video. |

Checklist for External XLR Mic with XLR Adapter

Checklist for External Recorders (Tascam DR-40)

| 1. | Do two recordings: one on-camera for reference and backup and the other externally. Choose your microphone type and follow the previous checklist for minijack on-camera recording. For DSLR shooters, don't worry about an external XLR adapter because that just complicates the workflow. You could just use the camera's mic, but if you hook up a Rode VideoMic Pro, for example, you'll get usable sound, so if something did go wrong in the external recording, you'll have a backup. |

| 2. | Most audio recorders contain a tripod screw hole, so you can mount the recorder onto its own tripod, if desired, or mount it to a DSLR rig. |

| 3. | Put fresh batteries into the recorder. |

| 4. | Choose your microphone for the digital audio recorder (XLR shotgun, XLR lav, or both—using the two different inputs) and hook it up to a boom pole, pistol grip, or tripod. Make sure it's no more than three feet away. |

| 5. | Attach the XLR cable to the mic and the input of the audio recorder (if you're using two mics, plug both into the recorder). |

| 6. | Set your audio recorder's audio compression scheme; be sure it matches the camera's recording capabilities (it'll most likely be 44.1 kHz, 16-bit or 48 kHz, 24-bit). Some recorders can do 96-bit, which will give you an even better recording to work with in post. Just be sure the kilohertz (44.1 kHz or 48 kHz) matches the camera setting. |

| 7. | Unless you're using a field mixer with limiters (such as the MixPre), set the max levels of your audio to 212 dBu (keep the levels below –6 on the meter) to help prevent clipping if a performer or subject gets too loud. This will give you 12 decibels of head-room. |

| 8. | Turn on the phantom power (it'll be either 48 V or 12 V). If you have a 12 V option, you may want to use this to save battery life, but be sure your mic can utilize 12 V of power. Otherwise, just stick with 48 V. |

| 9. | Plug in your headphones. There's a separate volume control for the headphones, but what you're hearing isn't exactly what you're actually recording! |

| 10. | Press Record on the digital audio recorder. The first time you press the Record button, it'll flash red and provide an audio level signal so you can test your levels before actually recording. |

| 11. | Set your levels by doing an audio test. |

| 12. | Press the Record button a second time to start recording. Double-check the timelapse clock to see if it's ticking; this will assure you that you're recording the audio! |

| 13. | Start recording on the camera. |

| 14. | Clap your hands or use a slate. |

| 15. | Begin the scene. |

| 16. | When the scene is completed, press the Stop button. (If you press the Pause button, you will keep one file if you press the Stop, then each time you record, a new file will be created—which is useful when recording multiple takes of video.) |

| 17. | Take note of the file number on the audio recorder, so you can match it to the right take on the camera. |

| 18. | Export the camera's video-audio footage into your computer. This will need to be processed (see the Chapter 6 on postproduction workflow). When you process it, keep the audio in its native format (44.1 kHz or 48 kHz). This audio will be your synced reference audio. |

| 19. | Export the audio from the audio recorder. You'll use this audio to replace the camera audio after you've synced it using the synchronization feature of Final Cut Pro X or DualEyes (see Chapter 6), or if you do it manually. |

This chapter should have provided you with the tools to get the quality sound you need for your film projects. The next chapter covers the final toolkit for the filmmaker: postproduction workflow for audio and video.

1 XLR inputs are not the savior of good audio! Some argue against using DSLRs because they lack XLR inputs—I've taught some form of video production for over 12 years; most of that time was dedicated to using prosumer video cameras containing XLR inputs, but I would still get bad audio from some students. And I have some students now who will record with a Zoom H4n, and they'll still get bad recordings—not because they're using a DSLR, but because if you do not know now to place a mic properly or set levels correctly it doesn't matter if the camera contains XLR inputs or not—a bad mic placement will result in poor audio and improper levels.