12. Object-Oriented Programming: Inheritance

Objectives

In this chapter you’ll learn:

![]() To create classes by inheriting from existing classes.

To create classes by inheriting from existing classes.

![]() How inheritance promotes software reuse.

How inheritance promotes software reuse.

![]() The notions of base classes and derived classes and the relationships between them.

The notions of base classes and derived classes and the relationships between them.

![]() The

The protected member access specifier.

![]() The use of constructors and destructors in inheritance hierarchies.

The use of constructors and destructors in inheritance hierarchies.

![]() The order in which constructors and destructors are called in inheritance hierarchies.

The order in which constructors and destructors are called in inheritance hierarchies.

![]() The differences between

The differences between public, protected and private inheritance.

![]() The use of inheritance to customize existing software.

The use of inheritance to customize existing software.

Say not you know another entirely, till you have divided an inheritance with him.

—Johann Kasper Lavater

This method is to define as the number of a class the class of all classes similar to the given class.

—Bertrand Russell

Good as it is to inherit a library, it is better to collect one.

—Augustine Birrell

Save base authority from others’ books.

—William Shakespeare

Outline

This chapter continues our discussion of object-oriented programming (OOP) by introducing another of its key features—inheritance. Inheritance is a form of software reuse in which you create a class that absorbs an existing class’s data and behaviors and enhances them with new capabilities. Software reusability saves time during program development. It also encourages the reuse of proven, debugged, high-quality software, which increases the likelihood that a system will be implemented effectively.

When creating a class, instead of writing completely new data members and member functions, you can designate that the new class should inherit the members of an existing class. This existing class is called the base class, and the new class is referred to as the derived class. (Other programming languages, such as Java, refer to the base class as the superclass and the derived class as the subclass.) A derived class represents a more specialized group of objects. Typically, a derived class contains behaviors inherited from its base class plus additional behaviors. As we’ll see, a derived class can also customize behaviors inherited from the base class. A direct base class is the base class from which a derived class explicitly inherits. An indirect base class is inherited from two or more levels up in the class hierarchy. In the case of single inheritance, a class is derived from one base class. C++ also supports multiple inheritance, in which a derived class inherits from multiple (possibly unrelated) base classes. Single inheritance is straightforward—we show several examples that should enable you to become proficient quickly. Multiple inheritance can be complex and error prone. We discuss multiple inheritance in Chapter 22, Other Topics.

C++ offers public, protected and private inheritance. In this chapter, we concentrate on public inheritance and briefly explain the other two. The private inheritance and protected inheritance forms are rarely used. With public inheritance, every object of a derived class is also an object of that derived class’s base class. However, base-class objects are not objects of their derived classes. For example, if we have vehicle as a base class and car as a derived class, then all cars are vehicles, but not all vehicles are cars. As we continue our study of object-oriented programming in this chapter and Chapter 13, we take advantage of this relationship to perform some interesting manipulations.

Experience in building software systems indicates that significant amounts of code deal with closely related special cases. When you are preoccupied with special cases, the details can obscure the big picture. With object-oriented programming, you focus on the commonalities among objects in the system rather than on the special cases.

We distinguish between the is-a relationship and the has-a relationship. The is-a relationship represents inheritance. In an is-a relationship, an object of a derived class also can be treated as an object of its base class—for example, a car is a vehicle, so any attributes and behaviors of a vehicle are also attributes and behaviors of a car. By contrast, the has-a relationship represents composition. (Composition was discussed in Chapter 10.) In a has-a relationship, an object contains one or more objects of other classes as members. For example, a car includes many components—it has a steering wheel, has a brake pedal, has a transmission and has many other components.

Derived-class member functions might require access to base-class data members and member functions. A derived class can access the non-private members of its base class. Base-class members that should not be accessible to the member functions of derived classes should be declared private in the base class. A derived class can effect state changes in private base-class members, but only through non-private member functions provided in the base class and inherited into the derived class.

Software Engineering Observation 12.1

Member functions of a derived class cannot directly access private members of the base class.

Software Engineering Observation 12.2

If a derived class could access its base class’s private members, classes that inherit from that derived class could access that data as well. This would propagate access to what should be private data, and the benefits of information hiding would be lost.

One problem with inheritance is that a derived class can inherit data members and member functions it does not need or should not have. It is the class designer’s responsibility to ensure that the capabilities provided by a class are appropriate for future derived classes. Even when a base-class member function is appropriate for a derived class, the derived class often requires that the member function behave in a manner specific to the derived class. In such cases, the base-class member function can be redefined in the derived class with an appropriate implementation.

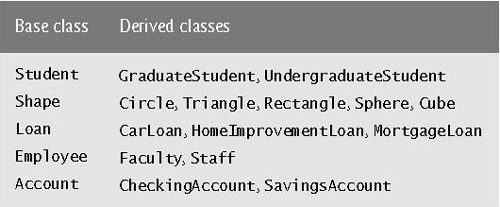

Often, an object of one class is an object of another class, as well. For example, in geometry, a rectangle is a quadrilateral (as are squares, parallelograms and trapezoids). Thus, in C++, class Rectangle can be said to inherit from class Quadrilateral. In this context, class Quadrilateral is a base class, and class Rectangle is a derived class. A rectangle is a specific type of quadrilateral, but it is incorrect to claim that a quadrilateral is a rectangle—the quadrilateral could be a parallelogram or some other shape. Figure 12.1 lists several simple examples of base classes and derived classes.

Because every derived-class object is an object of its base class, and one base class can have many derived classes, the set of objects represented by a base class typically is larger than the set of objects represented by any of its derived classes. For example, the base class Vehicle represents all vehicles, including cars, trucks, boats, airplanes, bicycles and so on. By contrast, derived class Car represents a smaller, more specific subset of all vehicles.

Inheritance relationships form treelike hierarchical structures. A base class exists in a hierarchical relationship with its derived classes. Although classes can exist independently, once they are employed in inheritance relationships, they become affiliated with other classes. A class becomes either a base class—supplying members to other classes, a derived class—inheriting its members from other classes, or both.

Let us develop a simple inheritance hierarchy with five levels (represented by the UML class diagram in Fig. 12.2). A university community has thousands of members.

These members consist of employees, students and alumni. Employees are either faculty members or staff members. Faculty members are either administrators (such as deans and department chairpersons) or teachers. Some administrators, however, also teach classes. Note that we have used multiple inheritance to form class AdministratorTeacher. Also note that this inheritance hierarchy could contain many other classes. For example, students can be graduate or undergraduate students. Undergraduate students can be freshmen, sophomores, juniors and seniors.

Each arrow in the hierarchy (Fig. 12.2) represents an is-a relationship. For example, as we follow the arrows in this class hierarchy, we can state “an Employee is a CommunityMember” and “a Teacher is a Faculty member.” CommunityMember is the direct base class of Employee, Student and Alumnus. In addition, CommunityMember is an indirect base class of all the other classes in the diagram. Starting from the bottom of the diagram, you can follow the arrows and apply the is-a relationship to the topmost base class. For example, an AdministratorTeacher is an Administrator, is a Faculty member, is an Employee and is a CommunityMember.

Now consider the Shape inheritance hierarchy in Fig. 12.3. This hierarchy begins with base class Shape. Classes TwoDimensionalShape and ThreeDimensionalShape derive from base class Shape—Shapes are either TwoDimensionalShapes or ThreeDimensionalShapes. The third level of this hierarchy contains some more specific types of TwoDimensionalShapes and ThreeDimensionalShapes. As in Fig. 12.2, we can follow the arrows from the bottom of the diagram to the topmost base class in this class hierarchy to identify several is-a relationships. For instance, a Triangle is a TwoDimensionalShape and is a Shape, while a Sphere is a ThreeDimensionalShape and is a Shape. Note that this hierarchy could contain many other classes, such as Rectangles, Ellipses and Trapezoids, which are all TwoDimensionalShapes.

To specify that class TwoDimensionalShape (Fig. 12.3) is derived from (or inherits from) class Shape, class TwoDimensionalShape’s definition could begin as follows:

class TwoDimensionalShape : public Shape

This is an example of public inheritance, the most commonly used form. We also will discuss private inheritance and protected inheritance (Section 12.6). With all forms of inheritance, private members of a base class are not accessible directly from that class’s derived classes, but these private base-class members are still inherited (i.e., they are still considered parts of the derived classes). With public inheritance, all other base-class members retain their original member access when they become members of the derived class (e.g., public members of the base class become public members of the derived class, and, as we’ll soon see, protected members of the base class become protected members of the derived class). Through these inherited base-class members, the derived class can manipulate private members of the base class (if these inherited members provide such functionality in the base class). Note that friend functions are not inherited.

Inheritance is not appropriate for every class relationship. In Chapter 10, we discussed the has-a relationship, in which classes have members that are objects of other classes. Such relationships create classes by composition of existing classes. For example, given the classes Employee, BirthDate and TelephoneNumber, it is improper to say that an Employee is a BirthDate or that an Employee is a TelephoneNumber. However, it is appropriate to say that an Employee has a BirthDate and that an Employee has a TelephoneNumber.

It is possible to treat base-class objects and derived-class objects similarly; their commonalities are expressed in the members of the base class. Objects of all classes derived from a common base class can be treated as objects of that base class (i.e., such objects have an is-a relationship with the base class). In Chapter 13, we consider many examples that take advantage of this relationship.

Chapter 3 introduced access specifiers public and private. A base class’s public members are accessible within the body of that base class and anywhere that the program has a handle (i.e., a name, reference or pointer) to an object of that base class or one of its derived classes. A base class’s private members are accessible only within the body of that base class and the friends of that base class. In this section, we introduce an additional access specifier: protected.

Using protected access offers an intermediate level of protection between public and private access. A base class’s protected members can be accessed within the body of that base class, by members and friends of that base class, and by members and friends of any classes derived from that base class.

Derived-class member functions can refer to public and protected members of the base class simply by using the member names. When a derived-class member function redefines a base-class member function, the base-class member can be accessed from the derived class by preceding the base-class member name with the base-class name and the binary scope resolution operator (::). We discuss accessing redefined members of the base class in Section 12.4 and using protected data in Section 12.4.4.

In this section, we use an inheritance hierarchy containing types of employees in a company’s payroll application to discuss the relationship between a base class and a derived class. Commission employees (who will be represented as objects of a base class) are paid a percentage of their sales, while base-salaried commission employees (who will be represented as objects of a derived class) receive a base salary plus a percentage of their sales. We divide our discussion of the relationship between commission employees and base-salaried commission employees into a carefully paced series of five examples:

1. In the first example, we create class CommissionEmployee, which contains as private data members a first name, last name, social security number, commission rate (percentage) and gross (i.e., total) sales amount.

2. The second example defines class BasePlusCommissionEmployee, which contains as private data members a first name, last name, social security number, commission rate, gross sales amount and base salary. We create the latter class by writing every line of code the class requires—we’ll soon see that it is much more efficient to create this class simply by inheriting from class CommissionEmployee.

3. The third example defines a new version of class BasePlusCommissionEmployee class that inherits directly from class CommissionEmployee (i.e., a BasePlusCommissionEmployee is a CommissionEmployee who also has a base salary) and attempts to access class CommissionEmployee’s private members—this results in compilation errors, because the derived class does not have access to the base class’s private data.

4. The fourth example shows that if CommissionEmployee’s data is declared as protected, a new version of class BasePlusCommissionEmployee that inherits from class CommissionEmployee can access that data directly. For this purpose, we define a new version of class CommissionEmployee with protected data. Both the inherited and noninherited BasePlusCommissionEmployee classes contain identical functionality, but we show how the version of BasePlusCommissionEmployee that inherits from class CommissionEmployee is easier to create and manage.

5. After we discuss the convenience of using protected data, we create the fifth example, which sets the CommissionEmployee data members back to private to enforce good software engineering. This example demonstrates that derived class BasePlusCommissionEmployee can use base class CommissionEmployee’s public member functions to manipulate CommissionEmployee’s private data.

Let’s examine CommissionEmployee’s class definition (Figs. 12.4–12.5). The CommissionEmployee header file (Fig. 12.4) specifies class CommissionEmployee’s public services, which include a constructor (lines 12–13) and member functions earnings (line 30) and print (line 31). Lines 15–28 declare public get and set functions that manipulate the class’s data members (declared in lines 33–37) firstName, lastName, socialSecurityNumber, grossSales and commissionRate. The CommissionEmployee header file specifies that these data members are private, so objects of other classes cannot directly access this data. Declaring data members as private and providing non-private get and set functions to manipulate and validate the data members helps enforce good software engineering. Member functions setGrossSales (defined in lines 57–60 of Fig. 12.5) and setCommissionRate (defined in lines 69–72 of Fig. 12.5), for example, validate their arguments before assigning the values to data members grossSales and commissionRate, respectively.

Fig. 12.4 CommissionEmployee class header file.

1 // Fig. 12.4: CommissionEmployee.h

2 // CommissionEmployee class definition represents a commission employee.

3 #ifndef COMMISSION_H

4 #define COMMISSION_H

5

6 #include <string> // C++ standard string class

7 using std::string;

8

9 class CommissionEmployee

10 {

11 public:

12 CommissionEmployee( const string &, const string &, const string &,

13 double = 0.0, double = 0.0 );

14

15 void setFirstName( const string & ); // set first name

16 string getFirstName( ) const; // return first name

17

18 void setLastName( const string & ); // set last name

19 string getLastName( ) const;// return last name

20

21 void setSocialSecurityNumber( const string & ); // set SSN

22 string getSocialSecurityNumber( ) const; // return SSN

23

24 void setGrossSales( double ); // set gross sales amount

25 double getGrossSales( ) const; // return gross sales amount

26

27 void setCommissionRate( double ); // set commission rate (percentage)

28 double getCommissionRate( ) const; // return commission rate

29

30 double earnings( ) const; // calculate earnings

31 void print( ) const; // print CommissionEmployee object

32 private:

33 string firstName;

34 string lastName;

35 string socialSecurityNumber;

36 double grossSales; // gross weekly sales

37 double commissionRate; // commission percentage

38 }; // end class CommissionEmployee

39

40 #endif

Fig. 12.5 Implementation file for CommissionEmployee class that represents an employee who is paid a percentage of gross sales.

1 // Fig. 12.5: CommissionEmployee.cpp

2 // Class CommissionEmployee member-function definitions.

3 #include <iostream>

4 using std::cout;

5

6 #include "CommissionEmployee.h" // CommissionEmployee class definition

7

8 // constructor

9 CommissionEmployee::CommissionEmployee(

10 const string &first, const string &last, const string &ssn,

11 double sales, double rate )

12 {

13 firstName = first; // should validate

14 lastName = last; // should validate

15 socialSecurityNumber = ssn; // should validate

16 setGrossSales( sales ); // validate and store gross sales

17 setCommissionRate( rate ); // validate and store commission rate

18 } // end CommissionEmployee constructor

19

20 // set first name

21 void CommissionEmployee::setFirstName( const string & first )

22 {

23 firstName = first; // should validate

24 } // end function setFirstName

25

26 // return first name

27 string CommissionEmployee::getFirstName( ) const

28 {

29 return firstName;

30 } // end function getFirstName

31

32 // set last name

33 void CommissionEmployee::setLastName( const string &last )

34 {

35 lastName = last; // should validate

36 } // end function setLastName

37

38 // return last name

39 string CommissionEmployee::getLastName( ) const

40 {

41 return lastName;

42 } // end function getLastName

43

44 // set social security number

45 void CommissionEmployee::setSocialSecurityNumber( const string &ssn )

46 {

47 socialSecurityNumber = ssn; // should validate

48 } // end function setSocialSecurityNumber

49

50 // return social security number

51 string CommissionEmployee::getSocialSecurityNumber( ) const

52 {

53 return socialSecurityNumber;

54 } // end function getSocialSecurityNumber

55

56 // set gross sales amount

57 void CommissionEmployee::setGrossSales( double sales )

58 {

59 grossSales = ( sales < 0.0 ) ? 0.0 : sales;

60 } // end function setGrossSales

61

62 // return gross sales amount

63 double CommissionEmployee::getGrossSales( ) const

64 {

65 return grossSales;

66 } // end function getGrossSales

67

68 // set commission rate

69 void CommissionEmployee::setCommissionRate( double rate )

70 {

71 commissionRate = ( rate > 0.0 && rate < 1.0 ) ? rate : 0.0;

72 } // end function setCommissionRate

73

74 // return commission rate

75 double CommissionEmployee::getCommissionRate( ) const

76 {

77 return commissionRate;

78 } // end function getCommissionRate

79

80 // calculate earnings

81 double CommissionEmployee::earnings( ) const

82 {

83 return commissionRate * grossSales;

84 } // end function earnings

85

86 // print CommissionEmployee object

87 void CommissionEmployee::print( ) const

88 {

89 cout << "commission employee: " << firstName << ' ' << lastName

90 << "

social security number: " << socialSecurityNumber

91 << "

gross sales: " << grossSales

92 << "

commission rate: " << commissionRate;

93 } // end function print

The CommissionEmployee constructor definition purposely does not use member-initializer syntax in the first several examples of this section, so that we can demonstrate how private and protected specifiers affect member access in derived classes. As shown in Fig. 12.5, lines 13–15, we assign values to data members firstName, lastName and socialSecurityNumber in the constructor body. Later in this section, we’ll return to using member-initializer lists in the constructors.

Note that we do not validate the values of the constructor’s arguments first, last and ssn before assigning them to the corresponding data members. We certainly could validate the first and last names—perhaps by ensuring that they are of a reasonable length. Similarly, a social security number could be validated to ensure that it contains nine digits, with or without dashes (e.g., 123-45-6789 or 123456789).

Member function earnings (lines 81–84) calculates a CommissionEmployee’s earnings. Line 83 multiplies the commissionRate by the grossSales and returns the result. Member function print (lines 87–93) displays the values of a CommissionEmployee object’s data members.

Figure 12.6 tests class CommissionEmployee. Lines 16–17 instantiate object employee of class CommissionEmployee and invoke CommissionEmployee’s constructor to initialize the object with "Sue" as the first name, "Jones" as the last name, "222-22-2222" as the social security number, 10000 as the gross sales amount and .06 as the commission rate. Lines 23–29 use employee’s get functions to display the values of its data members. Lines 31–32 invoke the object’s member functions setGrossSales and setCommissionRate to change the values of data members grossSales and commissionRate, respectively. Line 36 then calls employee’s print member function to output the updated CommissionEmployee information. Finally, line 39 displays the CommissionEmployee’s earnings, calculated by the object’s earnings member function using the updated values of data members grossSales and commissionRate.

Fig. 12.6 CommissionEmployee class test program.

1 // Fig. 12.6: fig12_06.cpp

2 // Testing class CommissionEmployee.

3 #include <iostream>

4 using std::cout;

5 using std::endl;

6 using std::fixed;

7

8 #include <iomanip>

9 using std::setprecision;

10

11 #include "CommissionEmployee.h" // CommissionEmployee class definition

12

13 int main( )

14 {

15 // instantiate a CommissionEmployee object

16 CommissionEmployee employee(

17 "Sue", "Jones", "222-22-2222", 10000, .06 );

18

19 // set floating-point output formatting

20 cout << fixed << setprecision( 2 );

21

22 // get commission employee data

23 cout << "Employee information obtained by get functions:

"

24 << "

First name is " << employee.getFirstName( )

25 << "

Last name is " << employee.getLastName( )

26 << "

Social security number is "

27 << employee.getSocialSecurityNumber( )

28 << "

Gross sales is " << employee.getGrossSales( )

29 << "

Commission rate is " << employee.getCommissionRate( ) << endl;

30

31 employee.setGrossSales( 8000 ); // set gross sales

32 employee.setCommissionRate( .1 ); // set commission rate

33

34 cout << "

Updated employee information output by print function:

"

35 << endl;

36 employee.print( ); // display the new employee information

37

38 // display the employee's earnings

39 cout << "

Employee's earnings: $" << employee.earnings( ) << endl;

40

41 return 0;

42 } // end main

Employee information obtained by get functions:

First name is Sue

Last name is Jones

Social security number is 222-22-2222

Gross sales is 10000.00

Commission rate is 0.06

Updated employee information output by print function:

commission employee: Sue Jones

social security number: 222-22-2222

gross sales: 8000.00

commission rate: 0.10

Employee's earnings: $800.00

We now discuss the second part of our introduction to inheritance by creating and testing (a completely new and independent) class BasePlusCommissionEmployee (Figs. 12.7–12.8), which contains a first name, last name, social security number, gross sales amount, commission rate and base salary.

Fig. 12.7 BasePlusCommissionEmployee class header file.

1 // Fig. 12.7: BasePlusCommissionEmployee.h

2 // BasePlusCommissionEmployee class definition represents an employee

3 // that receives a base salary in addition to commission.

4 #ifndef BASEPLUS_H

5 #define BASEPLUS_H

6

7 #include <string> // C++ standard string class

8 using std::string;

9

10 class BasePlusCommissionEmployee

11 {

12 public:

13 BasePlusCommissionEmployee( const string &, const string &,

14 const string &, double = 0.0, double = 0.0, double = 0.0 );

15

16 void setFirstName( const string & ); // set first name

17 string getFirstName( ) const; // return first name

18

19 void setLastName( const string & ); // set last name

20 string getLastName( ) const; // return last name

21

22 void setSocialSecurityNumber( const string & ); // set SSN

23 string getSocialSecurityNumber( ) const; // return SSN

24

25 void setGrossSales( double ); // set gross sales amount

26 double getGrossSales( ) const; // return gross sales amount

27

28 void setCommissionRate( double ); // set commission rate

29 double getCommissionRate( ) const; // return commission rate

30

31 void setBaseSalary( double ); // set base salary

32 double getBaseSalary( ) const; // return base salary

33

34 double earnings( ) const; // calculate earnings

35 void print( ) const; // print BasePlusCommissionEmployee object

36 private:

37 string firstName;

38 string lastName;

39 string socialSecurityNumber;

40 double grossSales; // gross weekly sales

41 double commissionRate; // commission percentage

42 double baseSalary; // base salary

43 }; // end class BasePlusCommissionEmployee

44

45 #endif

Fig. 12.8 BasePlusCommissionEmployee class represents an employee who receives a base salary in addition to a commission.

1 // Fig. 12.8: BasePlusCommissionEmployee.cpp

2 // Class BasePlusCommissionEmployee member-function definitions.

3 #include <iostream>

4 using std::cout;

5

6 // BasePlusCommissionEmployee class definition

7 #include "BasePlusCommissionEmployee.h"

8

9 // constructor

10 BasePlusCommissionEmployee::BasePlusCommissionEmployee(

11 const string &first, const string &last,const string &ssn,

12 double sales, double rate, double salary )

13 {

14 firstName = first; // should validate

15 lastName = last; // should validate

16 socialSecurityNumber = ssn; // should validate

17 setGrossSales( sales ); // validate and store gross sales

18 setCommissionRate( rate ); // validate and store commission rate

19 setBaseSalary( salary ); // validate and store base salary

20 } // end BasePlusCommissionEmployee constructor

21

22 // set first name

23 void BasePlusCommissionEmployee::setFirstName( const string &first )

24 {

25 firstName = first; // should validate

26 } // end function setFirstName

27

28 // return first name

29 string BasePlusCommissionEmployee::getFirstName( ) const

30 {

31 return firstName;

32 } // end function getFirstName

33

34 // set last name

35 void BasePlusCommissionEmployee::setLastName( const string &last )

36 {

37 lastName = last; // should validate

38 } // end function setLastName

39

40 // return last name

41 string BasePlusCommissionEmployee::getLastName( ) const

42 {

43 return lastName;

44 } // end function getLastName

45

46 // set social security number

47 void BasePlusCommissionEmployee::setSocialSecurityNumber(

48 const string &ssn )

49 {

50 socialSecurityNumber = ssn; // should validate

51 } // end function setSocialSecurityNumber

52

53 // return social security number

54 string BasePlusCommissionEmployee::getSocialSecurityNumber( ) const

55 {

56 return socialSecurityNumber;

57 } // end function getSocialSecurityNumber

58

59 // set gross sales amount

60 void BasePlusCommissionEmployee::setGrossSales( double sales )

61 {

62 grossSales = ( sales < 0.0 ) ? 0.0 : sales;

63 } // end function setGrossSales

64

65 // return gross sales amount

66 double BasePlusCommissionEmployee::getGrossSales( ) const

67 {

68 return grossSales;

69 } // end function getGrossSales

70

71 // set commission rate

72 void BasePlusCommissionEmployee::setCommissionRate( double rate )

73 {

74 commissionRate = ( rate > 0.0 && rate < 1.0 ) ? rate :0.0;

75 } // end function setCommissionRate

76

77 // return commission rate

78 double BasePlusCommissionEmployee::getCommissionRate( ) const

79 {

80 return commissionRate;

81 } // end function getCommissionRate

82

83 // set base salary

84 void BasePlusCommissionEmployee::setBaseSalary( double salary )

85 {

86 baseSalary = ( salary < 0.0 ) ? 0.0 : salary;

87 } // end function setBaseSalary

88

89 // return base salary

90 double BasePlusCommissionEmployee::getBaseSalary( ) const

91 {

92 return baseSalary;

93 } // end function getBaseSalary

94

95 // calculate earnings

96 double BasePlusCommissionEmployee::earnings( ) const

97 {

98 return baseSalary + ( commissionRate * grossSales );

99 } // end function earnings

100

101 // print BasePlusCommissionEmployee object

102 void BasePlusCommissionEmployee::print( ) const

103 {

104 cout << "base-salaried commission employee: " << firstName << ' '

105 << lastName << "

social security number: " << socialSecurityNumber

106 << "

gross sales: " << grossSales

107 << "

commission rate: " << commissionRate

108 << "

base salary: " << baseSalary;

109 } // end function print

The BasePlusCommissionEmployee header file (Fig. 12.7) specifies class BasePlusCommissionEmployee’s public services, which include the BasePlusCommissionEmployee constructor (lines 13–14) and member functions earnings (line 34) and print (line 35). Lines 16–32 declare public get and set functions for the class’s private data members (declared in lines 37–42) firstName, lastName, socialSecurityNumber, grossSales, commissionRate and baseSalary. These variables and member functions encapsulate all the necessary features of a base-salaried commission employee. Note the similarity between this class and class CommissionEmployee (Figs. 12.4–12.5)—in this example, we will not yet exploit that similarity.

Class BasePlusCommissionEmployee’s earnings member function (defined in lines 96–99 of Fig. 12.8) computes the earnings of a base-salaried commission employee. Line 98 returns the result of adding the employee’s base salary to the product of the commission rate and the employee’s gross sales.

Figure 12.9 tests class BasePlusCommissionEmployee. Lines 17–18 instantiate object employee of class BasePlusCommissionEmployee, passing "Bob", "Lewis", "333-33-3333", 5000, .04 and 300 to the constructor as the first name, last name, social security number, gross sales, commission rate and base salary, respectively. Lines 24–31 use BasePlusCommissionEmployee’s get functions to retrieve the values of the object’s data members for output. Line 33 invokes the object’s setBaseSalary member function to change the base salary. Member function setBaseSalary (Fig. 12.8, lines 84–87) ensures that data member baseSalary is not assigned a negative value, because an employee’s base salary cannot be negative. Line 37 of Fig. 12.9 invokes the object’s print member function to output the updated BasePlusCommissionEmployee’s information, and line 40 calls member function earnings to display the BasePlusCommissionEmployee’s earnings.

Fig. 12.9 BasePlusCommissionEmployee class test program.

1 // Fig. 12.9: fig12_09.cpp

2 // Testing class BasePlusCommissionEmployee.

3 #include <iostream>

4 using std::cout;

5 using std::endl;

6 using std::fixed;

7

8 #include <iomanip>

9 using std::setprecision;

10

11 // BasePlusCommissionEmployee class definition

12 #include "BasePlusCommissionEmployee.h"

13

14 int main( )

15 {

16 // instantiate BasePlusCommissionEmployee object

17 BasePlusCommissionEmployee

18 employee( "Bob", "Lewis", "333-33-3333", 5000, .04, 300 );

19

20 // set floating-point output formatting

21 cout << fixed << setprecision( 2 );

22

23 // get commission employee data

24 cout << "Employee information obtained by get functions:

"

25 << "

First name is " << employee.getFirstName( )

26 << "

Last name is " << employee.getLastName( )

27 << "

Social security number is "

28 << employee.getSocialSecurityNumber( )

29 << "

Gross sales is " << employee.getGrossSales( )

30 << "

Commission rate is " << employee.getCommissionRate( )

31 << "

Base salary is " << employee.getBaseSalary( ) << endl;

32

33 employee.setBaseSalary( 1000 ); // set base salary

34

35 cout << "

Updated employee information output by print function:

"

36 << endl;

37 employee.print( ); // display the new employee information

38

39 // display the employee's earnings

40 cout << "

Employee's earnings: $" <<employee.earnings( ) << endl;

41

42 return 0;

43 } // end main

Employee information obtained by get functions:

First name is Bob

Last name is Lewis

Social security number is 333-33-3333

Gross sales is 5000.00

Commission rate is 0.04

Base salary is 300.00

Updated employee information output by print function:

base-salaried commission employee: Bob Lewis

social security number: 333-33-3333

gross sales: 5000.00

commission rate: 0.04

base salary: 1000.00

Employee's earnings: $1200.00

Note that most of the code for class BasePlusCommissionEmployee (Figs. 12.7–12.8) is similar, if not identical, to the code for class CommissionEmployee (Figs. 12.4–12.5). For example, in class BasePlusCommissionEmployee, private data members firstName and lastName and member functions setFirstName, getFirstName, setLastName and getLastName are identical to those of class CommissionEmployee. Classes CommissionEmployee and BasePlusCommissionEmployee also both contain private data members socialSecurityNumber, commissionRate and grossSales, as well as get and set functions to manipulate these members. In addition, the BasePlusCommissionEmployee constructor is almost identical to that of class CommissionEmployee, except that BasePlusCommissionEmployee’s constructor also sets the baseSalary. The other additions to class BasePlusCommissionEmployee are private data member baseSalary and member functions setBaseSalary and getBaseSalary. Class BasePlusCommissionEmployee’s print member function is nearly identical to that of class CommissionEmployee, except that BasePlusCommissionEmployee’s print also outputs the value of data member baseSalary.

We literally copied code from class CommissionEmployee and pasted it into class BasePlusCommissionEmployee, then modified class BasePlusCommissionEmployee to include a base salary and member functions that manipulate the base salary. This “copy-and-paste” approach is error prone and time consuming. Worse yet, it can spread many physical copies of the same code throughout a system, creating a code-maintenance nightmare. Is there a way to “absorb” the data members and member functions of a class in a way that makes them part of another class without duplicating code? In the next several examples, we do exactly this, using inheritance.

Software Engineering Observation 12.3

Copying and pasting code from one class to another can spread errors across multiple source code files. To avoid duplicating code (and possibly errors), use inheritance, rather than the “copy-and-paste” approach, in situations where you want one class to “absorb” the data members and member functions of another class.

Software Engineering Observation 12.4

With inheritance, the common data members and member functions of all the classes in the hierarchy are declared in a base class. When changes are required for these common features, you need to make the changes only in the base class—derived classes then inherit the changes. Without inheritance, changes would need to be made to all the source code files that contain a copy of the code in question.

Now we create and test a new BasePlusCommissionEmployee class (Figs. 12.10–12.11) that derives from class CommissionEmployee (Figs. 12.4–12.5). In this example, a BasePlusCommissionEmployee object is a CommissionEmployee (because inheritance passes on the capabilities of class CommissionEmployee), but class BasePlusCommissionEmployee also has data member baseSalary (Fig. 12.10, line 24). The colon (:) in line 12 of the class definition indicates inheritance. Keyword public indicates the type of inheritance. As a derived class (formed with public inheritance), BasePlusCommissionEmployee inherits all the members of class CommissionEmployee, except for the constructor—each class provides its own constructors that are specific to the class. [Note that destructors, too, are not inherited.] Thus, the public services of BasePlusCommissionEmployee include its constructor (lines 15–16) and the public member functions inherited from class CommissionEmployee—although we cannot see these inherited member functions in BasePlusCommissionEmployee’s source code, they are nevertheless a part of derived class BasePlusCommissionEmployee. The derived class’s public services also include member functions setBaseSalary, getBaseSalary, earnings and print (lines 18–22).

Fig. 12.10 BasePlusCommissionEmployee class definition indicating inheritance relationship with class CommissionEmployee.

1 // Fig. 12.10: BasePlusCommissionEmployee.h

2 // BasePlusCommissionEmployee class derived from class

3 // CommissionEmployee.

4 #ifndef BASEPLUS_H

5 #define BASEPLUS_H

6

7 #include <string> // C++ standard string class

8 using std::string;

9

10 #include "CommissionEmployee.h" // CommissionEmployee class declaration

11

12 class BasePlusCommissionEmployee : public CommissionEmployee

13 {

14 public:

15 BasePlusCommissionEmployee( const string &, const string &,

16 const string &, double = 0.0, double = 0.0, double = 0.0 );

17

18 void setBaseSalary( double ); // set base salary

19 double getBaseSalary( ) const; // return base salary

20

21 double earnings( ) const; // calculate earnings

22 void print( ) const; // print BasePlusCommissionEmployee object

23 private:

24 double baseSalary; // base salary

25 }; // end class BasePlusCommissionEmployee

26

27 #endif

Fig. 12.11 BasePlusCommissionEmployee implementation file: private base-class data cannot be accessed from derived class.

1 // Fig. 12.11: BasePlusCommissionEmployee.cpp

2 // Class BasePlusCommissionEmployee member-function definitions.

3 #include <iostream>

4 using std::cout;

5

6 // BasePlusCommissionEmployee class definition

7 #include "BasePlusCommissionEmployee.h"

8

9 // constructor

10 BasePlusCommissionEmployee::BasePlusCommissionEmployee(

11 const string &first, const string &last, const string &ssn,

12 double sales, double rate, double salary )

13 // explicitly call base-class constructor

14 : CommissionEmployee( first, last, ssn, sales, rate )

15 {

16 setBaseSalary( salary ); // validate and store base salary

17 } // end BasePlusCommissionEmployee constructor

18

19 // set base salary

20 void BasePlusCommissionEmployee::setBaseSalary( double salary )

21 {

22 baseSalary = ( salary < 0.0 ) ? 0.0 : salary;

23 } // end function setBaseSalary

24

25 // return base salary

26 double BasePlusCommissionEmployee::getBaseSalary( ) const

27 {

28 return baseSalary;

29 } // end function getBaseSalary

30

31 // calculate earnings

32 double BasePlusCommissionEmployee::earnings( ) const

33 {

34 // derived class cannot access the base class's private data

35 return baseSalary + ( commissionRate * grossSales );

36 } // end function earnings

37

38 // print BasePlusCommissionEmployee object

39 void BasePlusCommissionEmployee::print( ) const

40 {

41 // derived class cannot access the base class's private data

42 cout << "base-salaried commission employee: " << firstName << ' '

43 << lastName << "

social security number: " << socialSecurityNumber

44 << "

gross sales: " << grossSales

45 << "

commission rate: " << commissionRate

46 << "

base salary: " << baseSalary;

47 } // end function print

C:cppfp_examplesch12Fig12_10_11BasePlusCommissionEmployee.cpp(35) :

error C2248: 'CommissionEmployee::commissionRate' :

cannot access private member declared in class 'CommissionEmployee'

C:cppfp_examplesch12Fig12_10_11CommissionEmployee.h(37) :

see declaration of 'CommissionEmployee::commissionRate'

C:cppfp_examplesch12Fig12_10_11CommissionEmployee.h(10) :

see declaration of 'CommissionEmployee'

C:cppfp_examplesch12Fig12_10_11BasePlusCommissionEmployee.cpp(35) :

error C2248: 'CommissionEmployee::grossSales' :

cannot access private member declared in class 'CommissionEmployee'

C:cppfp_examplesch12Fig12_10_11CommissionEmployee.h(36) :

see declaration of 'CommissionEmployee::grossSales'

C:cppfp_examplesch12Fig12_10_11CommissionEmployee.h(10) :

see declaration of 'CommissionEmployee'

C:cppfp_examplesch12Fig12_10_11BasePlusCommissionEmployee.cpp(42) :

error C2248: 'CommissionEmployee::firstName' :

cannot access private member declared in class 'CommissionEmployee'

C:cppfp_examplesch12Fig12_10_11CommissionEmployee.h(33) :

see declaration of 'CommissionEmployee::firstName'

C:cppfp_examplesch12Fig12_10_11CommissionEmployee.h(10) :

see declaration of 'CommissionEmployee'

C:cppfp_examplesch12Fig12_10_11BasePlusCommissionEmployee.cpp(43) :

error C2248: 'CommissionEmployee::lastName' :

cannot access private member declared in class 'CommissionEmployee'

C:cppfp_examplesch12Fig12_10_11CommissionEmployee.h(34) :

see declaration of 'CommissionEmployee::lastName'

C:cppfp_examplesch12Fig12_10_11CommissionEmployee.h(10) :

see declaration of 'CommissionEmployee'

C:cppfp_examplesch12Fig12_10_11BasePlusCommissionEmployee.cpp(43) :

error C2248: 'CommissionEmployee::socialSecurityNumber' :

cannot access private member declared in class 'CommissionEmployee'

C:cppfp_examplesch12Fig12_10_11CommissionEmployee.h(35) :

see declaration of 'CommissionEmployee::socialSecurityNumber'

C:cppfp_examplesch12Fig12_10_11CommissionEmployee.h(10) :

see declaration of 'CommissionEmployee'

C:cppfp_examplesch12Fig12_10_11BasePlusCommissionEmployee.cpp(44) :

error C2248: 'CommissionEmployee::grossSales' :

cannot access private member declared in class 'CommissionEmployee'

C:cppfp_examplesch12Fig12_10_11CommissionEmployee.h(36) :

see declaration of 'CommissionEmployee::grossSales'

C:cppfp_examplesch12Fig12_10_11CommissionEmployee.h(10) :

see declaration of 'CommissionEmployee'

C:cppfp_examplesch12Fig12_10_11BasePlusCommissionEmployee.cpp(45) :

error C2248: 'CommissionEmployee::commissionRate' :

cannot access private member declared in class 'CommissionEmployee'

C:cppfp_examplesch12Fig12_10_11CommissionEmployee.h(37) :

see declaration of 'CommissionEmployee::commissionRate'

C:cppfp_examplesch12Fig12_10_11CommissionEmployee.h(10) :

see declaration of 'CommissionEmployee'

Figure 12.11 shows BasePlusCommissionEmployee’s member-function implementations. The constructor (lines 10–17) introduces base-class initializer syntax (line 14), which uses a member initializer to pass arguments to the base-class (CommissionEmployee) constructor. C++ requires that a derived-class constructor call its base-class constructor to initialize the base-class data members that are inherited into the derived class. Line 14 accomplishes this task by invoking the CommissionEmployee constructor by name, passing the constructor’s parameters first, last, ssn, sales and rate as arguments to initialize base-class data members firstName, lastName, socialSecurityNumber, grossSales and commissionRate. If BasePlusCommissionEmployee’s constructor did not invoke class CommissionEmployee’s constructor explicitly, C++ would attempt to invoke class CommissionEmployee’s default constructor—but the class does not have such a constructor, so the compiler would issue an error. Recall from Chapter 3 that the compiler provides a default constructor with no parameters in any class that does not explicitly include a constructor. However, CommissionEmployee does explicitly include a constructor, so a default constructor is not provided, and any attempts to implicitly call CommissionEmployee’s default constructor would result in compilation errors.

Common Programming Error 12.1

A compilation error occurs if a derived-class constructor calls one of its base-class constructors with arguments that are inconsistent with the number and types of parameters specified in one of the base-class constructor definitions.

Performance Tip 12.1

In a derived-class constructor, initializing member objects and invoking base-class constructors explicitly in the member initializer list prevents duplicate initialization in which a default constructor is called, then data members are modified again in the derived-class constructor’s body.

The compiler generates errors for line 35 of Fig. 12.11 because base class CommissionEmployee’s data members commissionRate and grossSales are private—derived class BasePlusCommissionEmployee’s member functions are not allowed to access base class CommissionEmployee’s private data. Note that we used bold black text in Fig. 12.11 to indicate erroneous code. The compiler issues additional errors in lines 42–45 of BasePlusCommissionEmployee’s print member function for the same reason. As you can see, C++ rigidly enforces restrictions on accessing private data members, so that even a derived class (which is intimately related to its base class) cannot access the base class’s private data. [Note: To save space, we show only the error messages from Visual C++ 2005 in this example. The error messages produced by your compiler may differ from those shown here. Also notice that we highlight key portions of the lengthy error messages in bold.]

We purposely included the erroneous code in Fig. 12.11 to emphasize that a derived class’s member functions cannot access its base class’s private data. The errors in BasePlusCommissionEmployee could have been prevented by using the get member functions inherited from class CommissionEmployee. For example, line 35 could have invoked getCommissionRate and getGrossSales to access CommissionEmployee’s private data members commissionRate and grossSales, respectively. Similarly, lines 42–45 could have used appropriate get member functions to retrieve the values of the base class’s data members. In the next example, we show how using protected data also allows us to avoid the errors encountered in this example.

Notice that we #include the base class’s header file in the derived class’s header file (line 10 of Fig. 12.10). This is necessary for three reasons. First, for the derived class to use the base class’s name in line 12, we must tell the compiler that the base class exists—the class definition in CommissionEmployee.h does exactly that.

The second reason is that the compiler uses a class definition to determine the size of an object of that class (as we discussed in Section 3.8). A client program that creates an object of a class must #include the class definition to enable the compiler to reserve the proper amount of memory for the object. When using inheritance, a derived-class object’s size depends on the data members declared explicitly in its class definition and the data members inherited from its direct and indirect base classes. Including the base class’s definition in line 10 allows the compiler to determine the memory requirements for the base class’s data members that become part of a derived-class object and thus contribute to the total size of the derived-class object.

The last reason for line 10 is to allow the compiler to determine whether the derived class uses the base class’s inherited members properly. For example, in the program of Figs. 12.10–12.11, the compiler uses the base-class header file to determine that the data members being accessed by the derived class are private in the base class. Since these are inaccessible to the derived class, the compiler generates errors. The compiler also uses the base class’s function prototypes to validate function calls made by the derived class to the inherited base-class functions—you’ll see an example of such a function call in Fig. 12.16.

In Section 3.9, we discussed the linking process for creating an executable GradeBook application. In that example, you saw that the client’s object code was linked with the object code for class GradeBook, as well as the object code for any C++ Standard Library classes used in either the client code or in class GradeBook.

The linking process is similar for a program that uses classes in an inheritance hierarchy. The process requires the object code for all classes used in the program and the object code for the direct and indirect base classes of any derived classes used by the program. Suppose a client wants to create an application that uses class BasePlusCommissionEmployee, which is a derived class of CommissionEmployee (we’ll see an example of this in Section 12.4.4). When compiling the client application, the client’s object code must be linked with the object code for classes BasePlusCommissionEmployee and CommissionEmployee, because BasePlusCommissionEmployee inherits member functions from its base class CommissionEmployee. The code is also linked with the object code for any C++ Standard Library classes used in class CommissionEmployee, class BasePlusCommissionEmployee or the client code. This provides the program with access to the implementations of all of the functionality that the program may use.

To enable class BasePlusCommissionEmployee to directly access CommissionEmployee data members firstName, lastName, socialSecurityNumber, grossSales and commissionRate, we can declare those members as protected in the base class. As we discussed in Section 12.3, a base class’s protected members can be accessed by members and friends of the base class and by members and friends of any classes derived from that base class.

Good Programming Practice 12.1

Declare public members first, protected members second and private members last.

Class CommissionEmployee (Figs. 12.12–12.13) now declares data members firstName, lastName, socialSecurityNumber, grossSales grossSales and, commissionRate as protected (Fig. 12.12, lines 33–37) rather than private. The member-function implementations in Fig. 12.13 are identical to those in Fig. 12.5.

Fig. 12.12 CommissionEmployee class definition that declares protected data to allow access by derived classes.

1 // Fig. 12.12: CommissionEmployee.h

2 // CommissionEmployee class definition with protected data.

3 #ifndef COMMISSION_H

4 #define COMMISSION_H

5

6 #include <string> // C++ standard string class

7 using std::string;

8

9 class CommissionEmployee

10 {

11 public:

12 CommissionEmployee( const string &, const string &, const string &,

13 double = 0.0, double = 0.0 );

14

15 void setFirstName( const string & );// set first name

16 string getFirstName( ) const; // return first name

17

18 void setLastName( const string & );// set last name

19 string getLastName( ) const; // return last name

20

21 void setSocialSecurityNumber( const string & ); // set SSN

22 string getSocialSecurityNumber( ) const; // return SSN

23

24 void setGrossSales( double ); // set gross sales amount

25 double getGrossSales( ) const; // return gross sales amount

26

27 void setCommissionRate( double ); // set commission rate

28 double getCommissionRate( ) const; // return commission rate

29

30 double earnings( ) const; // calculate earnings

31 void print( ) const; // print CommissionEmployee object

32 protected:

33 string firstName;

34 string lastName;

35 string socialSecurityNumber;

36 double grossSales; // gross weekly sales

37 double commissionRate; // commission percentage

38 }; // end class CommissionEmployee

39

40 #endif

Fig. 12.13 CommissionEmployee class with protected data.

1 // Fig. 12.13: CommissionEmployee.cpp

2 // Class CommissionEmployee member-function definitions.

3 #include <iostream>

4 using std::cout;

5

6 #include "CommissionEmployee.h" // CommissionEmployee class definition

7

8 // constructor

9 CommissionEmployee::CommissionEmployee(

10 const string &first, const string &last, const string &ssn,

11 double sales, double rate )

12 {

13 firstName = first; // should validate

14 lastName = last; // should validate

15 socialSecurityNumber = ssn; // should validate

16 setGrossSales( sales ); // validate and store gross sales

17 setCommissionRate( rate ); // validate and store commission rate

18 } // end CommissionEmployee constructor

19

20 // set first name

21 void CommissionEmployee::setFirstName( const string &first )

22 {

23 firstName = first; // should validate

24 } // end function setFirstName

25

26 // return first name

27 string CommissionEmployee::getFirstName( ) const

28 {

29 return firstName;

30 } // end function getFirstName

31

32 // set last name

33 void CommissionEmployee::setLastName( const string &last )

34 {

35 lastName = last; // should validate

36 } // end function setLastName

37

38 // return last name

39 string CommissionEmployee::getLastName( ) const

40 {

41 return lastName;

42 } // end function getLastName

43

44 // set social security number

45 void CommissionEmployee::setSocialSecurityNumber( const string &ssn )

46 {

47 socialSecurityNumber = ssn; // should validate

48 } // end function setSocialSecurityNumber

49

50 // return social security number

51 string CommissionEmployee::getSocialSecurityNumber( ) const

52 {

53 return socialSecurityNumber;

54 } // end function getSocialSecurityNumber

55

56 // set gross sales amount

57 void CommissionEmployee::setGrossSales( double sales )

58 {

59 grossSales = ( sales < 0.0 ) ? 0.0 : sales;

60 } // end function setGrossSales

61

62 // return gross sales amount

63 double CommissionEmployee::getGrossSales( ) const

64 {

65 return grossSales;

66 } // end function getGrossSales

67

68 // set commission rate

69 void CommissionEmployee::setCommissionRate( double rate )

70 {

71 commissionRate = ( rate > 0.0 && rate < 1.0 ) ? rate : 0.0;

72 } // end function setCommissionRate

73

74 // return commission rate

75 double CommissionEmployee::getCommissionRate( ) const

76 {

77 return commissionRate;

78 } // end function getCommissionRate

79

80 // calculate earnings

81 double CommissionEmployee::earnings( ) const

82 {

83 return commissionRate * grossSales;

84 } // end function earnings

85

86 // print CommissionEmployee object

87 void CommissionEmployee::print( ) const

88 {

89 cout << "commission employee: " << firstName << ' ' << lastName

90 << "

social security number: " << socialSecurityNumber

91 << "

gross sales: " << grossSales

92 << "

commission rate: " << commissionRate;

93 } // end function print

We now modify class BasePlusCommissionEmployee (Figs. 12.14–12.15) so that it inherits from the class CommissionEmployee in Figs. 12.12–12.13. Because class BasePlusCommissionEmployee inherits from this version of class CommissionEmployee, objects of class BasePlusCommissionEmployee can access inherited data members that are declared protected in class CommissionEmployee (i.e., data members firstName, lastName, socialSecurityNumber, grossSales and commissionRate). As a result, the compiler does not generate errors when compiling the BasePlusCommissionEmployee earnings and print member-function definitions in Fig. 12.15 (lines 32–36 and 39–47, respectively). This shows the special privileges that a derived class is granted to access protected base-class data members. Objects of a derived class also can access protected members in any of that derived class’s indirect base classes.

Fig. 12.14 BasePlusCommissionEmployee class header file.

1 // Fig. 12.14: BasePlusCommissionEmployee.h

2 // BasePlusCommissionEmployee class derived from class

3 // CommissionEmployee.

4 #ifndef BASEPLUS_H

5 #define BASEPLUS_H

6

7 #include <string> // C++ standard string class

8 using std::string;

9

10 #include "CommissionEmployee.h" // CommissionEmployee class declaration

11

12 class BasePlusCommissionEmployee : public CommissionEmployee

13 {

14 public:

15 BasePlusCommissionEmployee( const string &, const string &,

16 const string &, double = 0.0, double = 0.0, double = 0.0 );

17

18 void setBaseSalary( double ); // set base salary

19 double getBaseSalary( ) const; // return base salary

20

21 double earnings( ) const; // calculate earnings

22 void print( ) const; // print BasePlusCommissionEmployee object

23 private:

24 double baseSalary; // base salary

25 }; // end class BasePlusCommissionEmployee

26

27 #endif

Fig. 12.15 BasePlusCommissionEmployee implementation file for BasePlusCommissionEmployee class that inherits protected data from CommissionEmployee.

1 // Fig. 12.15: BasePlusCommissionEmployee.cpp

2 // Class BasePlusCommissionEmployee member-function definitions.

3 #include <iostream>

4 using std::cout;

5

6 // BasePlusCommissionEmployee class definition

7 #include "BasePlusCommissionEmployee.h"

8

9 // constructor

10 BasePlusCommissionEmployee::BasePlusCommissionEmployee(

11 const string &first, const string &last, const string &ssn,

12 double sales, double rate, double salary )

13 // explicitly call base-class constructor

14 : CommissionEmployee( first, last, ssn, sales, rate )

15 {

16 setBaseSalary( salary ); // validate and store base salary

17 } // end BasePlusCommissionEmployee constructor

18

19 // set base salary

20 void BasePlusCommissionEmployee::setBaseSalary( double salary )

21 {

22 baseSalary = ( salary < 0.0 ) ? 0.0 : salary;

23 } // end function setBaseSalary

24

25 // return base salary

26 double BasePlusCommissionEmployee::getBaseSalary( ) const

27 {

28 return baseSalary;

29 } // end function getBaseSalary

30

31 // calculate earnings

32 double BasePlusCommissionEmployee::earnings( ) const

33 {

34 // can access protected data of base class

35 return baseSalary + ( commissionRate * grossSales );

36 } // end function earnings

37

38 // print BasePlusCommissionEmployee object

39 void BasePlusCommissionEmployee::print( ) const

40 {

41 // can access protected data of base class

42 cout << "base-salaried commission employee: " << firstName << ' '

43 << lastName << "

social security number: " << socialSecurityNumber

44 << "

gross sales: " << grossSales

45 << "

commission rate: " << commissionRate

46 << "

base salary: " << baseSalary;

47 } // end function print

Class BasePlusCommissionEmployee does not inherit class CommissionEmployee constructor. However, class BasePlusCommissionEmployee’s constructor (Fig. 12.15, lines 10–17) calls class CommissionEmployee’s constructor explicitly with member initializer syntax (line 14). Recall that BasePlusCommissionEmployee’s constructor must explicitly call the constructor of class CommissionEmployee, because CommissionEmployee does not contain a default constructor that could be invoked implicitly.

Figure 12.16 uses a BasePlusCommissionEmployee object to perform the same tasks that Fig. 12.9 performed on an object of the first version of class BasePlusCommissionEmployee (Figs. 12.7–12.8). Note that the outputs of the two programs are identical. We created the first class BasePlusCommissionEmployee without using inheritance and created this version of BasePlusCommissionEmployee using inheritance; however, both classes provide the same functionality. Note that the code for class BasePlusCommissionEmployee (i.e., the header and implementation files), which is 74 lines, is considerably shorter than the code for the noninherited version of the class, which is 154 lines, because the inherited version absorbs part of its functionality from CommissionEmployee, whereas the noninherited version does not absorb any functionality. Also, there is now only one copy of the CommissionEmployee functionality declared and defined in class CommissionEmployee. This makes the source code easier to maintain, modify and debug, because the source code related to a CommissionEmployee exists only in the files of Figs. 12.12–12.13.

Fig. 12.16 protected base-class data can be accessed from derived class.

1 // Fig. 12.16: fig12_16.cpp

2 // Testing class BasePlusCommissionEmployee.

3 #include <iostream>

4 using std::cout;

5 using std::endl;

6 using std::fixed;

7

8 #include <iomanip>

9 using std::setprecision;

10

11 // BasePlusCommissionEmployee class definition

12 #include "BasePlusCommissionEmployee.h"

13

14 int main( )

15 {

16 // instantiate BasePlusCommissionEmployee object

17 BasePlusCommissionEmployee

18 employee( "Bob", "Lewis", "333-33-3333", 5000, .04, 300 );

19

20 // set floating-point output formatting

21 cout << fixed << setprecision( 2 );

22

23 // get commission employee data

24 cout << "Employee information obtained by get functions:

"

25 << "

First name is " << employee.getFirstName( )

26 << "

Last name is " << employee.getLastName( )

27 << "

Social security number is "

28 << employee.getSocialSecurityNumber( )

29 << "

Gross sales is " << employee.getGrossSales( )

30 << "

Commission rate is " << employee.getCommissionRate( )

31 << "

Base salary is " << employee.getBaseSalary( ) << endl;

32

33 employee.setBaseSalary( 1000 ); // set base salary

34

35 cout << "

Updated employee information output by print function:

"

36 << endl;

37 employee.print( ); // display the new employee information

38

39 // display the employee's earnings

40 cout << "

Employee's earnings: $" << employee.earnings( ) << endl;

41

42 return 0;

43 } // end main

Employee information obtained by get functions:

First name is Bob

Last name is Lewis

Social security number is 333-33-3333

Gross sales is 5000.00

Commission rate is 0.04

Base salary is 300.00

Updated employee information output by print function:

base-salaried commission employee: Bob Lewis

social security number: 333-33-3333

gross sales: 5000.00

commission rate: 0.04

base salary: 1000.00

Employee's earnings: $1200.00

In this example, we declared base-class data members as protected, so derived classes can modify the data directly. Inheriting protected data members slightly increases performance, because we can directly access the members without incurring the overhead of calls to set or get member functions. In most cases, however, it is better to use private data members to encourage proper software engineering, and leave code optimization issues to the compiler. Your code will be easier to maintain, modify and debug.

Using protected data members creates two serious problems. First, the derived-class object does not have to use a member function to set the value of the base class’s protected data member. Therefore, a derived-class object easily can assign an invalid value to the protected data member, thus leaving the object in an inconsistent state. For example, with CommissionEmployee’s data member grossSales declared as protected, a derived-class (e.g., BasePlusCommissionEmployee) object can assign a negative value to grossSales. The second problem with using protected data members is that derived-class member functions are more likely to be written so that they depend on the base-class implementation. In practice, derived classes should depend only on the base-class services (i.e., non-private member functions) and not on the base-class implementation. With protected data members in the base class, if the base-class implementation changes, we may need to modify all derived classes of that base class. For example, if for some reason we were to change the names of data members firstName and lastName to first and last, then we would have to do so for all occurrences in which a derived class references these base-class data members directly. In such a case, the software is said to be fragile or brittle, because a small change in the base class can “break” derived-class implementation. You should be able to change the base-class implementation while still providing the same services to derived classes. (Of course, if the base-class services change, we must reimplement our derived classes—good object-oriented design attempts to prevent this.)

Software Engineering Observation 12.5

It is appropriate to use the protected access specifier when a base class should provide a service (i.e., a member function) only to its derived classes (and friends), not to other clients.

Software Engineering Observation 12.6

Declaring base-class data members private (as opposed to declaring them protected) enables programmers to change the base-class implementation without having to change derived-class implementations.

We now reexamine our hierarchy once more, this time using the best software engineering practices. Class CommissionEmployee (Figs. 12.17–12.18) now declares data members firstName, lastName, socialSecurityNumber, grossSales and commissionRate as private (Fig. 12.17, lines 33–37) and provides public member functions setFirstName, getFirstName, setLastName, getLastName, setSocialSecurityNumber, getSocialSecurityNumber, setGrossSales, getGrossSales, setCommissionRate, getCommissionRate, earnings and print for manipulating these values. If we decide to change the data member names, the earnings and print definitions will not require modification—only the definitions of the get and set member functions that directly manipulate the data members will need to change. Note that these changes occur solely within the base class—no changes to the derived class are needed. Localizing the effects of changes like this is a good software engineering practice. Derived class BasePlusCommissionEmployee (Figs. 12.19–12.20) inherits CommissionEmployee’s non-private member functions and can access the private base-class members via those member functions.

Fig. 12.17 CommissionEmployee class defined using good software engineering practices.

1 // Fig. 12.17: CommissionEmployee.h

2 // CommissionEmployee class definition with good software engineering.

3 #ifndef COMMISSION_H

4 #define COMMISSION_H

5

6 #include <string> // C++ standard string class

7 using std::string;

8

9 class CommissionEmployee

10 {

11 public:

12 CommissionEmployee( const string &, const string &, const string &,

13 double = 0.0, double = 0.0 );

14

15 void setFirstName( const string & ); // set first name

16 string getFirstName( ) const; // return first name

17

18 void setLastName( const string & ); // set last name

19 string getLastName( ) const; // return last name

20

21 void setSocialSecurityNumber( const string & ); // set SSN

22 string getSocialSecurityNumber( ) const; // return SSN

23

24 void setGrossSales( double ); // set gross sales amount

25 double getGrossSales( ) const; // return gross sales amount

26

27 void setCommissionRate( double ); // set commission rate

28 double getCommissionRate( ) const; // return commission rate

29

30 double earnings( ) const; // calculate earnings

31 void print( ) const; // print CommissionEmployee object

32 private:

33 string firstName;

34 string lastName;

35 string socialSecurityNumber;

36 double grossSales; // gross weekly sales

37 double commissionRate; // commission percentage

38 }; // end class CommissionEmployee

39

40 #endif

Fig. 12.18 CommissionEmployee class implementation file: CommissionEmployee class uses member functions to manipulate its private data.

1 // Fig. 12.18: CommissionEmployee.cpp

2 // Class CommissionEmployee member-function definitions.

3 #include <iostream>

4 using std::cout;

5

6 #include "CommissionEmployee.h" // CommissionEmployee class definition

7

8 // constructor

9 CommissionEmployee::CommissionEmployee(

10 const string &first, const string &last, const string &ssn,

11 double sales, double rate )

12 : firstName( first ), lastName( last ), socialSecurityNumber( ssn )

13 {

14 setGrossSales( sales ); // validate and store gross sales

15 setCommissionRate( rate ); // validate and store commission rate

16 } // end CommissionEmployee constructor

17

18 // set first name

19 void CommissionEmployee::setFirstName( const string &first )

20 {

21 firstName = first; // should validate

22 } // end function setFirstName

23

24 // return first name

25 string CommissionEmployee::getFirstName( ) const

26 {

27 return firstName;

28 } // end function getFirstName

29

30 // set last name

31 void CommissionEmployee::setLastName( const string &last )

32 {

33 lastName = last; // should validate

34 } // end function setLastName

35

36 // return last name

37 string CommissionEmployee::getLastName( ) const

38 {

39 return lastName;

40 } // end function getLastName

41

42 // set social security number

43 void CommissionEmployee::setSocialSecurityNumber( const string &ssn )

44 {

45 socialSecurityNumber = ssn; // should validate

46 } // end function setSocialSecurityNumber

47

48 // return social security number

49 string CommissionEmployee::getSocialSecurityNumber( ) const

50 {

51 return socialSecurityNumber;

52 } // end function getSocialSecurityNumber

53

54 // set gross sales amount

55 void CommissionEmployee::setGrossSales( double sales )

56 {

57 grossSales = ( sales < 0.0 ) ? 0.0 : sales;

58 } // end function setGrossSales

59

60 // return gross sales amount

61 double CommissionEmployee::getGrossSales( ) const

62 {

63 return grossSales;

64 } // end function getGrossSales

65

66 // set commission rate

67 void CommissionEmployee::setCommissionRate( double rate )

68 {

69 commissionRate = ( rate > 0.0 && rate < 1.0 ) ? rate : 0.0;

70 } // end function setCommissionRate

71

72 // return commission rate

73 double CommissionEmployee::getCommissionRate( ) const

74 {

75 return commissionRate;

76 } // end function getCommissionRate

77

78 // calculate earnings

79 double CommissionEmployee::earnings( ) const

80 {

81 return getCommissionRate( ) * getGrossSales( ) ;

82 } // end function earnings

83

84 // print CommissionEmployee object

85 void CommissionEmployee::print( ) const

86 {

87 cout << "commission employee: "

88 << getFirstName( ) << ' ' << getLastName( )

89 << "

social security number: " << getSocialSecurityNumber( )

90 << "

gross sales: " << getGrossSales( )

91 << "

commission rate: " << getCommissionRate( );

92 } // end function print

In the CommissionEmployee constructor implementation (Fig. 12.18, lines 9–16), note that we use member initializers (line 12) to set the values of members firstName, lastName and socialSecurityNumber. We show how derived-class BasePlusCommissionEmployee (Figs. 12.19–12.20) can invoke non-private base-class member functions (setFirstName, getFirstName, setLastName, getLastName, setSocialSecurityNumber and getSocialSecurityNumber) to manipulate these data members.

Fig. 12.19 BasePlusCommissionEmployee class header file.

1 // Fig. 12.19: BasePlusCommissionEmployee.h

2 // BasePlusCommissionEmployee class derived from class

3 // CommissionEmployee.

4 #ifndef BASEPLUS_H

5 #define BASEPLUS_H

6

7 #include <string> // C++ standard string class

8 using std::string;

9

10 #include "CommissionEmployee.h" // CommissionEmployee class declaration

11

12 class BasePlusCommissionEmployee : public CommissionEmployee

13 {

14 public:

15 BasePlusCommissionEmployee( const string &, const string &,

16 const string &, double = 0.0, double = 0.0, double = 0.0 );

17

18 void setBaseSalary( double ); // set base salary

19 double getBaseSalary( ) const; // return base salary

20

21 double earnings( ) const; // calculate earnings

22 void print( ) const; // print BasePlusCommissionEmployee object

23 private:

24 double baseSalary; // base salary

25 }; // end class BasePlusCommissionEmployee

26

27 #endif

Fig. 12.20 BasePlusCommissionEmployee class that inherits from class CommissionEmployee but cannot directly access the class’s private data.

1 // Fig. 12.20: BasePlusCommissionEmployee.cpp

2 // Class BasePlusCommissionEmployee member-function definitions.

3 #include <iostream>

4 using std::cout;

5

6 // BasePlusCommissionEmployee class definition

7 #include "BasePlusCommissionEmployee.h"

8

9 // constructor

10 BasePlusCommissionEmployee::BasePlusCommissionEmployee(

11 const string &first, const string &last, const string &ssn,

12 double sales, double rate, double salary )

13 // explicitly call base-class constructor

14 : CommissionEmployee( first, last, ssn, sales, rate )

15 {

16 setBaseSalary( salary ); // validate and store base salary

17 } // end BasePlusCommissionEmployee constructor

18

19 // set base salary