25

Automatic Vulnerability Discovery Using Fuzzers

Whenever I approach a new target, I prefer to search for bugs manually. Manual testing is great for discovering new and unexpected attack vectors. It can also help you learn new security concepts in depth. But manual testing also takes a lot of time and effort, so as with automating reconnaissance, you should strive to automate at least part of the process of finding bugs. Automated testing can help you tease out a large number of bugs within a short time frame.

In fact, the best-performing bug bounty hunters automate most of their hacking process. They automate their recon, and write programs that constantly look for vulnerabilities on the targets of their choice. Whenever their tools notify them of a potential vulnerability, they immediately verify and report it.

Bugs discovered through an automation technique called fuzzing, or fuzz testing, now account for a majority of new CVE entries. While often associated with the development of binary exploits, fuzzing can also be used for discovering vulnerabilities in web applications. In this chapter, we’ll talk a bit about fuzzing web applications by using two tools, Burp intruder and Wfuzz, and about what it can help you achieve.

What Is Fuzzing?

Fuzzing is the process of sending a wide range of invalid and unexpected data to an application and monitoring the application for exceptions. Sometimes hackers craft this invalid data for a specific purpose; other times, they generate it randomly or by using algorithms. In both cases, the goal is to induce unexpected behavior, like crashes, and then check if the error leads to an exploitable bug. Fuzzing is particularly useful for exposing bugs like memory leaks, control flow issues, and race conditions. For example, you can fuzz compiled binaries for vulnerabilities by using tools like the American Fuzzy Lop, or AFL (https://github.com/google/AFL/).

There are many kinds of fuzzing, each optimized for testing a specific type of issue in an application. Web application fuzzing is a technique that attempts to expose common web vulnerabilities, like injection issues, XSS, and authentication bypass.

How a Web Fuzzer Works

Web fuzzers automatically generate malicious requests by inserting the payloads of common vulnerabilities into web application injection points. They then fire off these requests and keep track of the server’s responses.

To better understand this process, let’s take a look at how the open source web application fuzzer Wfuzz (https://github.com/xmendez/wfuzz/) works. When provided with a wordlist and an endpoint, Wfuzz replaces all locations marked FUZZ with strings from the wordlist. For example, the following Wfuzz command will replace the instance of FUZZ inside the URL with every string in the common_paths.txt wordlist:

$ wfuzz -w common_paths.txt http://example.com/FUZZYou should provide a different wordlist for each type of vulnerability you scan for. For instance, you can make the fuzzer behave like a directory enumerator by supplying it with a wordlist of common filepaths. As a result, Wfuzz will generate requests that enumerate the paths on example.com:

http://example.com/admin

http://example.com/admin.php

http://example.com/cgi-bin

http://example.com/secure

http://example.com/authorize.php

http://example.com/cron.php

http://example.com/administratorYou can also make the fuzzer act like an IDOR scanner by providing it with potential ID values:

$ wfuzz -w ids.txt http://example.com/view_inbox?user_id=FUZZSay that ids.txt is a list of numeric IDs. If example.com/view_inbox is the endpoint used to access different users’ email inboxes, this command will cause Wfuzz to generate a series of requests that try to access other users’ inboxes, such as the following:

http://example.com/view_inbox?user_id=1

http://example.com/view_inbox?user_id=2

http://example.com/view_inbox?user_id=3Once you receive the server’s responses, you can analyze them to see if there really is a file in that particular path, or if you can access the email inbox of another user. As you can see, unlike vulnerability scanners, fuzzers are quite flexible in the vulnerabilities they test for. You can customize them to their fullest extent by specifying different payloads and injection points.

The Fuzzing Process

Now let’s go through the steps that you can take to integrate fuzzing into your hacking process! When you approach a target, how do you start fuzzing it? The process of fuzzing an application can be broken into four steps. You can start by determining the endpoints you can fuzz within an application. Then, decide on the payload list and start fuzzing. Finally, monitor the results of your fuzzer and look for anomalies.

Step 1: Determine the Data Injection Points

The first thing to do when fuzzing a web application is to identify the ways a user can provide input to the application. What are the endpoints that take user input? What are the parameters used? What headers does the application use? You can think of these parameters and headers as data injection points or data entry points, since these are the locations at which an attacker can inject data into an application.

By now, you should already have an intuition of which vulnerabilities you should look for on various user input opportunities. For example, when you see a numeric ID, you should test for IDOR, and when you see a search bar, you should test for reflected XSS. Classify the data injection points you’ve found on the target according to the vulnerabilities they are prone to:

Data entry points to test for IDORs

GET /email_inbox?user_id=FUZZ

Host: example.com

POST /delete_user

Host: example.com

(POST request parameter)

user_id=FUZZData entry points to test for XSS

GET /search?q=FUZZ

Host: example.com

POST /send_email

Host: example.com

(POST request parameter)

user_id=abc&title=FUZZ&body=FUZZStep 2: Decide on the Payload List

After you’ve identified the data injection points and the vulnerabilities that you might be able to exploit with each one, determine what data to feed to each injection point. You should fuzz each injection point with common payloads of the most likely vulnerabilities. Feeding XSS payloads and SQL injection payloads into most data entry points is also worthwhile.

Using a good payload list is essential to finding vulnerabilities with fuzzers. I recommend downloading SecLists by Daniel Miessler (https://github.com/danielmiessler/SecLists/) and Big List of Naughty Strings by Max Woolf (https://github.com/minimaxir/big-list-of-naughty-strings/) for a pretty comprehensive payload list useful for fuzzing web applications. Among other features, these lists include payloads for the most common web vulnerabilities, such as XXS, SQL injection, and XXE. Another good wordlist database for both enumeration and vulnerability fuzzing is FuzzDB (https://github.com/fuzzdb-project/fuzzdb/).

Besides using known payloads, you might try generating payloads randomly. In particular, create extremely long payloads, payloads that contain odd characters of various encodings, and payloads that contain certain special characters, like the newline character, the line-feed character, and more. By feeding the application garbage data like this, you might be able to detect unexpected behavior and discover new classes of vulnerabilities!

You can use bash scripts, which you learned about in Chapter 5, to automate the generation of random payloads. How would you generate a string of a random length that includes specific special characters? Hint: you can use a for loop or the file /dev/random on Unix systems.

Step 3: Fuzz

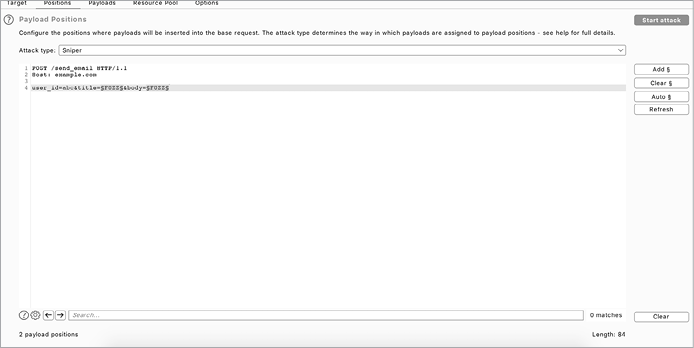

Next, systematically feed your payload list to the data entry points of the application. There are several ways of doing this, depending on your needs and programming skills. The simplest way to automate fuzzing is to use the Burp intruder (Figure 25-1). The intruder offers a fuzzer with a graphical user interface (GUI) that seamlessly integrates with your Burp proxy. Whenever you encounter a request you’d like to fuzz, you can right-click it and choose Send to Intruder.

In the Intruder tab, you can configure your fuzzer settings, select your data injection points and payload list, and start fuzzing. To add a part of the request as a data injection point, highlight the portion of the request and click Add on the right side of the window.

Figure 25-1: The Burp intruder payload position selection

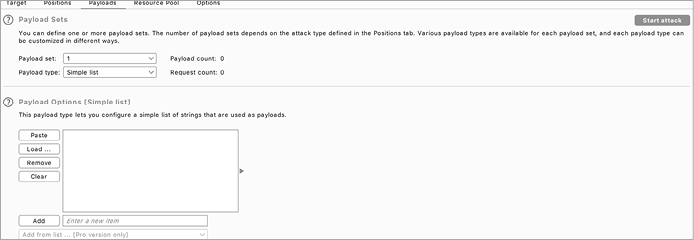

Then either select a predefined list of payloads or generate payload lists in the Payloads tab (Figure 25-2). For example, you could generate list of numbers or randomly generated alphanumeric strings.

Figure 25-2: Selecting the payload list in Burp intruder

Burp intruder is easy to use, but it has a downside: the free version of Burp limits the fuzzer’s functionality, and time-throttles its attacks, meaning that it slows your fuzzing and limits the number of requests you can send over a certain period of time. You’ll be able to send only a certain number of requests per minute, making the intruder a lot less efficient than a non-time-throttled fuzzer. Unless you need a GUI or have the professional version of Burp, you’re better off using an open source fuzzer like OWASP ZAP’s fuzzer or Wfuzz. You’ll learn how to fuzz a target with Wfuzz in “Fuzzing with Wfuzz” later on this page.

Note that sometimes throttling your fuzzers will be necessary to prevent disruption to the application’s operations. This shouldn’t be an issue for bigger companies, but you could accidentally launch a DoS attack on smaller companies without scaling architectures if you fuzz their applications without time throttling. Always use caution and obtain permission from the company when conducting fuzz testing!

Step 4: Monitor the Results

Analyze the results your fuzzer returned, looking for patterns and anomalies in the server responses. What to look for depends on the payload set you used and the vulnerability you’re hoping to find. For example, when you’re using a fuzzer to find filepaths, status codes are a good indicator of whether a file is present. If the returned status code for a pathname is in the 200 range, you might have discovered a valid path. If the status code is 404, on the other hand, the filepath probably isn’t valid.

When fuzzing for SQL injection, you might want to look for a change in response content length or time. If the returned content for a certain payload is longer than that of other payloads, it might indicate that your payload was able to influence the database’s operation and change what it returned. On the other hand, if you’re using a payload list that induces time delays in an application, check whether any of the payloads make the server respond more slowly than average. Use the knowledge you learned in this book to identify key indicators that a vulnerability is present.

Fuzzing with Wfuzz

Now that you understand the general approach to take, let’s walk through a hands-on example using Wfuzz, which you can install by using this command:

$ pip install wfuzzFuzzing is useful in both the recon phase and the hunting phase: you can use fuzzing to enumerate filepaths, brute-force authentication, test for common web vulnerabilities, and more.

Path Enumeration

During the recon stage, try using Wfuzz to enumerate filepaths on a server. Here’s a command you can use to enumerate filepaths on example.com:

$ wfuzz -w wordlist.txt -f output.txt --hc 404 --follow http://example.com/FUZZThe -w flag option specifies the wordlist to use for enumeration. In this case, you should pick a good path enumeration wordlist designed for the technology used by your target. The -f flag specifies the output file location. Here, we store our results into a file named output.txt in the current directory. The --hc 404 option tells Wfuzz to exclude any response that has a 404 status code. Remember that this code stands for File Not Found. With this filter, we can easily drop URLs that don’t point to a valid file or directory from the results list. The --follow flag tells Wfuzz to follow all HTTP redirections so that our result shows the URL’s actual destination.

Let’s run the command using a simple wordlist to see what we can find on facebook.com. For our purposes, let’s use a wordlist comprising just four words, called wordlist.txt:

authorize.php

cron.php

administrator

secureRun this command to enumerate paths on Facebook:

$ wfuzz -w wordlist.txt -f output.txt --hc 404 --follow http://facebook.com/FUZZLet’s take a look at the results. From left to right, a Wfuzz report has the following columns for each request: Request ID, HTTP Response Code, Response Length in Lines, Response Length in Words, Response Length in Characters, and the Payload Used:

********************************************************

* Wfuzz 2.4.6 - The Web Fuzzer *

********************************************************

Target: http://facebook.com/FUZZ

Total requests: 4

===================================================================

ID Response Lines Word Chars Payload

===================================================================

000000004: 200 20 L 2904 W 227381 Ch "secure"

Total time: 1.080132

Processed Requests: 4

Filtered Requests: 3

Requests/sec.: 3.703250You can see that these results contain only one response. This is because we filtered out irrelevant results. Since we dropped all 404 responses, we can now focus on the URLs that point to actual paths. It looks like /secure returned a 200 OK status code and is a valid path on facebook.com.

Brute-Forcing Authentication

Once you’ve gathered valid filepaths on the target, you might find that some of the pages on the server are protected. Most of the time, these pages will have a 403 Forbidden response code. What can you do then?

Well, you could try to brute-force the authentication on the page. For example, sometimes pages use HTTP’s basic authentication scheme as access control. In this case, you can use Wfuzz to fuzz the authentication headers, using the -H flag to specify custom headers:

$ wfuzz -w wordlist.txt -H "Authorization: Basic FUZZ" http://example.com/adminThe basic authentication scheme uses a header named Authorization to transfer credentials that are the base64-encoded strings of username and password pairs. For example, if your username and password were admin and password, your authentication string would be base64("admin:password"), or YWRtaW46cGFzc3dvcmQ=. You could generate authentication strings from common username and password pairs by using a script, then feed them to your target’s protected pages by using Wfuzz.

Another way to brute-force basic authentication is to use Wfuzz’s --basic option. This option automatically constructs authentication strings to brute-force basic authentication, given an input list of usernames and passwords. In Wfuzz, you can mark different injection points with FUZZ, FUZ2Z, FUZ3Z, and so on. These injection points will be fuzzed with the first, second, and third wordlist passed in, respectively. Here’s a command you can use to fuzz the username and password field at the same time:

$ wfuzz -w usernames.txt -w passwords.txt --basic FUZZ:FUZ2Z http://example.com/adminThe usernames.txt file contains two usernames: admin and administrator. The passwords.txt file contains three passwords: secret, pass, and password. As you can see, Wfuzz sends a request for each username and password combination from your lists:

********************************************************

* Wfuzz 2.4.6 - The Web Fuzzer *

********************************************************

Target: http://example.com/admin

Total requests: 6

===================================================================

ID Response Lines Word Chars Payload

===================================================================

000000002: 404 46 L 120 W 1256 Ch "admin – pass"

000000001: 404 46 L 120 W 1256 Ch "admin – secret"

000000003: 404 46 L 120 W 1256 Ch "admin – password"

000000006: 404 46 L 120 W 1256 Ch "administrator – password"

000000004: 404 46 L 120 W 1256 Ch "administrator – secret"

000000005: 404 46 L 120 W 1256 Ch "administrator – pass"

Total time: 0.153867

Processed Requests: 6

Filtered Requests: 0

Requests/sec.: 38.99447Other ways to bypass authentication by using brute-forcing include switching out the User-Agent header or forging custom headers used for authentication. You could accomplish all of these by using Wfuzz to brute-force HTTP request headers.

Testing for Common Web Vulnerabilities

Finally, Wfuzz can help you automatically test for common web vulnerabilities. First of all, you can use Wfuzz to fuzz URL parameters and test for vulnerabilities like IDOR and open redirects. Fuzz URL parameters by placing a FUZZ keyword in the URL. For example, if a site uses a numeric ID for chat messages, test various IDs by using this command:

$ wfuzz -w wordlist.txt http://example.com/view_message?message_id=FUZZThen find valid IDs by examining the response codes or content length of the response and see if you can access the messages of others. The IDs that point to valid pages usually return a 200 response code or a longer web page.

You can also insert payloads into redirect parameters to test for an open redirect:

$ wfuzz -w wordlist.txt http://example.com?redirect=FUZZTo check if a payload causes a redirect, turn on Wfuzz’s follow (--follow) and verbose (-v) options. The follow option instructs Wfuzz to follow redirects. The verbose option shows more detailed results, including whether redirects occurred during the request. See if you can construct a payload that redirects users to your site:

$ wfuzz -w wordlist.txt -v –-follow http://example.com?redirect=FUZZFinally, test for vulnerabilities such as XSS and SQL injection by fuzzing URL parameters, POST parameters, or other user input locations with common payload lists.

When testing for XSS by using Wfuzz, try creating a list of scripts that redirect the user to your page, and then turn on the verbose option to monitor for any redirects. Alternatively, you can use Wfuzz content filters to check for XSS payloads reflected. The --filter flag lets you set a result filter. An especially useful filter is content~STRING, which returns responses that contain whatever STRING is:

$ wfuzz -w xss.txt --filter "content~FUZZ" http://example.com/get_user?user_id=FUZZFor SQL injection vulnerabilities, try using a premade SQL injection wordlist and monitor for anomalies in the response time, response code, or response length of each payload. If you use SQL injection payloads that include time delays, look for long response times. If most payloads return a certain response code but one does not, investigate that response further to see if there’s a SQL injection there. A longer response length might also be an indication that you were able to extract data from the database.

The following command tests for SQL injection using the wordlist sqli.txt. You can specify POST body data with the -d flag:

$ wfuzz -w sqli.txt -d "user_id=FUZZ" http://example.com/get_userMore About Wfuzz

Wfuzz has many more advanced options, filters, and customizations that you can take advantage of. Used to its full potential, Wfuzz can automate the most tedious parts of your workflow and help you find more bugs. For more cool Wfuzz tricks, read its documentation at https://wfuzz.readthedocs.io/.

Fuzzing vs. Static Analysis

In Chapter 22, I discussed the effectiveness of source code review for discovering web vulnerabilities. You might now be wondering: why not just perform a static analysis of the code? Why conduct fuzz testing at all?

Static code analysis is an invaluable tool for identifying bugs and improper programming practices that attackers can exploit. However, static analysis has its limitations.

First, it evaluates an application in a non-live state. Performing code review on an application won’t let you simulate how the application will react when it’s running live and clients are interacting with it, and it’s very difficult to predict all the possible malicious inputs an attacker can provide.

Static code analysis also requires access to the application’s source code. When you’re doing a black-box test, as in a bug bounty scenario, you probably won’t be able to obtain the source code unless you can leak the application’s source code or identify the open source components the application is using. This makes fuzzing a great way of adding to your testing methodology, since you won’t need the source code to fuzz an application.

Pitfalls of Fuzzing

Of course, fuzzing isn’t a magic cure-all solution for all bug detection. This technique has certain limitations, one of which is rate-limiting by the server. During a remote, black-box engagement, you might not be able to send in large numbers of payloads to the application without the server detecting your activity, or you hitting some kind of rate limit. This can cause your testing to slow down or the server might ban you from the service.

In a black-box test, it can also be difficult to accurately evaluate the impact of the bug found through fuzzing, since you don’t have access to the code and so are getting a limited sample of the application’s behavior. You’ll often need to conduct further manual testing to classify the bug’s validity and significance. Think of fuzzing as a metal detector: it merely points you to the suspicious spots. In the end, you need to inspect more closely to see if you have found something of value.

Another limitation involves the classes of bugs that fuzzing can find. Although fuzzing is good at finding certain basic vulnerabilities like XSS and SQL injection, and can sometimes aid in the discovery of new bug types, it isn’t much help in detecting business logic errors, or bugs that require multiple steps to exploit. These complex bugs are a big source of potential attacks and still need to be teased out manually. While fuzzing should be an essential part of your testing process, it should by no means be the only part of it.

Adding to Your Automated Testing Toolkit

Automated testing tools like fuzzers or scanners can help you discover some bugs, but they often hinder your learning progress if you don’t take the time to understand how each tool in your testing toolkit works. Thus, before adding a tool to your workflow, be sure to take time to read the tool’s documentation and understand how it works. You should do this for all the recon and testing tools you use.

Besides reading the tool’s documentation, I also recommend reading its source code if it’s open source. This can teach you about the methodologies of other hackers and provide insight into how the best hackers in the field approach their testing. Finally, by learning how others automate hacking, you’ll begin learning how to write your own tools as well.

Here’s a challenge for you: read the source code of the tools Sublist3r (https://github.com/aboul3la/Sublist3r/) and Wfuzz (https://github.com/xmendez/wfuzz/). These are both easy-to-understand tools written in Python. Sublist3r is a subdomain enumeration tool, while Wfuzz is a web application fuzzer. How does Sublist3r approach subdomain enumeration? How does Wfuzz fuzz web applications? Can you write down their application logic, starting from the point at which they receive an input target and ending when they output their results? Can you rewrite the functionalities they implement using a different approach?

Once you’ve gained a solid understanding of how your tools work, try to modify them to add new features! If you think others would find your feature useful, you could contribute to the open source project: propose that your feature be added to the official version of the tool.

Understanding how your tools and exploits work is the key to becoming a master hacker. Good luck and happy hacking!