Chapter 5

The High Value of Low-Yielding Treasuries within the Balanced Portfolio Framework

Treasury bonds are government guaranteed instruments that promise to pay a fixed interest rate over time. The principal value of the bond has nearly zero risk of loss because the issuer, the U.S. government, effectively has the ability to print money to repay the bondholder. As a result, Treasuries are often considered to be risk-free. However, this is only true if you buy a bond and hold it to maturity. The price of Treasuries fluctuates every day because these bonds are publicly traded. The price moves as the future economic environment unfolds and as expectations of the future shift. Thus, you can lose money if the bond is sold prior to maturity. When I discuss Treasuries in this chapter and in this book, I am referring to bonds that are generally not held to maturity, as my emphasis is on trying to achieve stable returns through time. Thus, the volatility in the price of the bonds becomes an important consideration.

Introduction

In the last chapter we covered one of the most popular and widely owned asset classes, equities. In this chapter, we turn perhaps to the other end of the spectrum. Many investors believe that Treasuries, because of their low yields, are one of the least attractive asset classes. Today, Treasuries may be the one asset to which you are most averse. You might question why anyone in their right mind would invest in an asset class that offers a very low yield with limited upside and significant downside risk. It would be one thing if Treasuries were yielding double digits as they were in the 1980s, but yields near historic lows seem to make this an obviously poor asset class. This mind-set, while ostensibly reasonable, is extremely flawed.

I will begin the discussion about Treasuries with a review of this asset class as it is commonly viewed from a conventional perspective. Similarly to the approach taken with equities, most investors simply look at the expected return of Treasuries, which they base on their current yield, to assess their attractiveness. A low yield suggests poor future returns and therefore a bad investment. As a result, few investors choose to include this asset class in their portfolios. The major flaws in this thought process and conclusion will be detailed in the first part of this chapter.

The discussion will then turn to how Treasuries should be assessed when analyzed through a balanced portfolio lens. Not only will this new insight help you to better understand the important role of Treasuries in a balanced portfolio, but you will also more clearly appreciate the flaws in conventional thinking when viewing Treasuries using this different viewpoint.

The Conventional Perspective

As was described in the last chapter, the conventional approach to assessing the attractiveness of asset classes, including Treasuries, is to consider the upside. The main question that is asked is how much Treasuries can return over a reasonable time frame. Most investors look at the current yield as an indicator of the future return potential of Treasuries since the principal value is guaranteed. If interest rates are low relative to historical levels, then the assumption is that there is more downside risk than upside potential in Treasuries. This is because if rates are low, then they are more likely to rise than fall. Rising rates cause a loss in principal in Treasuries, while falling rates are a positive. This simplistic approach effectively covers the preponderance of the analysis done on this important asset class.

The current view of Treasuries from this perspective seems to make sense. In late 2007, the 10-year Treasury yield fell and stayed below 4 percent for the first time since the 1950s. Most investors concluded that interest rates were too low to warrant buying Treasuries. Many are absolutely convinced that the yield is far too unattractive to provide a decent expected return. As a result, since 2007 investors have reduced their exposure to Treasuries by replacing them with higher yielding, lower quality alternatives. In addition, investors have been shortening their bond portfolio's duration to protect against what they view to be an inevitable rise in interest rates.

Despite this conventional view, long-term Treasuries produced excess returns above cash of 44.1 percent from October 2007 through December 2013. This return far exceeded expectations and was stronger than the returns of the stock market during the same time frame. The S&P 500 Index beat cash by 36.1 percent during this time (nearly all of the gain coming in the final year—2013—of the measurement period). Many contend that the outsized returns of Treasuries have been an aberration that no one could have confidently predicted.

The truth is that underweighting Treasuries during the past six years has exposed the highly flawed belief that the only thing that really matters is the interest rate. The real mistake is not in the results, but in the perspective used. The most important message is for you to understand why Treasuries performed far better than many had expected and why the predictable reaction to low interest rates was misguided. After all, the results could have easily turned out differently. The objective is to provide you the needed insight to help minimize the likelihood of making a similar mistake in the future.

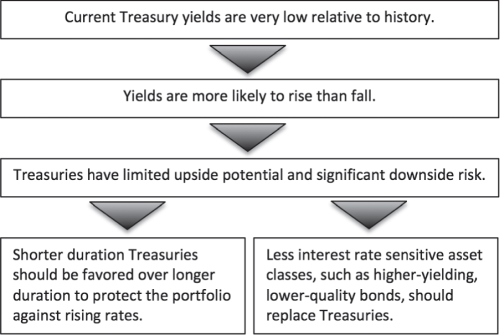

In the first section of this chapter I will walk you through the main arguments used in the conventional perspective and identify major oversights in each key point. The main argument for underweighting Treasury exposure follows a familiar logical sequence, which is laid out in Figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1 Conventional Thought Process for Underweighting Treasury Exposure

This conventional thought process contains several major flaws at each step of the argument. The first point that current Treasury yields are low is certainly true; however, the rest of the logic quickly falls apart. The flaws can be summarized into three groups:

- Interest rates have to rise more than expected in order to negatively impact Treasury excess returns.

- Long-term Treasuries can produce strong returns over shorter time frames despite a low starting yield.

- Cutting Treasury duration or replacing Treasuries with higher yielding, lower quality bonds makes portfolios less balanced and more risky.

I will address each of these major flaws separately.

Major Flaw #1: Interest Rates Have to Rise More than People Expect for Treasuries to Underperform Cash

Earlier in the book I emphasized the importance of breaking down returns into their core components. The return of cash plus the excess return above cash make up the total return of an asset class. Since the return of cash is risk-free, you should focus on the excess return above cash when analyzing asset class returns. You can get the cash rate with no risk, so if you are going to take risk you need to understand how much you can expect to be compensated.

When you decide to exchange cash for a long-term Treasury bond, you are effectively making a bet that you will be compensated a little more than what you would earn if you just held cash over time. Since both cash and Treasuries are considered risk-free in terms of principal value, you would only take the price risk associated with Treasuries if you were compensated with excess returns above cash. Since Treasuries are merely a longer-duration version of risk-free cash—because they, too, do not contain credit risk—the excess returns Treasuries offer are understandably low relative to other, riskier asset classes.

The actual excess return above cash that you will receive with your Treasury investment, like all other asset classes, depends on how events transpire relative to market expectations. The future discount is relatively straightforward to discern for Treasuries because it is reflected in the slope of the yield curve. Specifically, the yield curve tells us the market's expectation for the future path of cash rates. An upward sloping curve demonstrates the discounted increase in cash rates over time. Cash rates and short-term interest rates are nearly identical and are set by the Federal Reserve. The steeper the slope, the faster short-term interest rates are expected to rise.

Therefore, when you think about whether Treasuries are attractively priced relative to cash the key question to ask is whether you expect interest rates to rise faster than what is currently priced in. If you do, then you should underweight Treasuries (relative to an efficient, neutral mix); and if you don't, then you ought to hold more. For example, if cash is yielding 0 percent and long-term Treasuries are offering a 4 percent yield, then that implies that interest rates are expected to rise significantly over time. If they do rise, but less than priced in, then you would be better off buying Treasuries than holding cash. In this case Treasuries would earn excess returns above cash because cash rates rose less than expected.

From this perspective it should be apparent that contrary to the popular view, the current yield by itself does not matter. You need to look at the entire yield curve to identify what future conditions it is discounting. A 4 percent long-term Treasury yield means something very different when cash is yielding 0 percent versus when it is yielding 6 percent. At 0 percent, the yield curve is extremely steep and at 6 percent it is inverted (signifying the anticipation of falling short-term interest rates). In both cases, the excess return above cash is dependent on the future path of interest rates versus the discounted levels. In fact, since 1927 the correlation of future excess Treasury returns and the starting yield is just 10 percent or 0.1 (meaning there is effectively very little correlation between the two). The excess return depends on how the future plays out relative to what was already priced in (and you know that the odds of it going one way or another are about fifty-fifty).

To illustrate this point, let's review the yield and returns of Treasuries during the past six years. The 10-year Treasury fell below 4 percent in December 2007, at which time nearly every bond investor concluded that interest rates were near historic lows and destined to rise. Shortly thereafter at the onset of the financial crisis, short-term interest rates fell to almost 0 percent. With the framework described above, the appropriate way to have analyzed interest rates was to consider the steepness of the yield curve to gain a more complete perspective of what the low rates meant. Since everyone expected rates to rise, this market view was already reflected in the yield curve with low rates at the short end (the end closest to the present) and much higher relative rates at the long end (the end farther out).

A well-informed investor would have asked what has caused short-term rates to fall. Historically, interest rates have gone down to zero only in times of great distress and when there is need for massive monetary stimulation. The last time interest rates were near zero in the United States was during the Great Depression, and they stayed there for 15 years, from 1933 to 1948. In Japan, interest rates approached zero in 1995 and have remained there ever since (19 years and counting). Monetary policy dictates lowering short-term interest rates to stimulate growth. When interest rates are lowered to zero, that suggests that the economic environment is so fragile that zero rates are warranted. In today's environment, zero rates are in fact insufficient to stimulate growth because of the overly indebted balance sheets of many developed economies (the United States included). Thus the question to ask is how long short-term interest rates may stay near zero given the economic environment, as opposed to just automatically concluding that they must rise just because they are low. The timing is crucial because it ultimately drives long-duration bond excess returns to a greater degree than the starting yield.

The reason Treasuries performed so strongly was because everyone expected rates to rise rapidly, and instead rates fell. Why did they fall? Economic growth underperformed levels discounted in the market, which were far too optimistic given underlying economic conditions. This is a major oversight of the vast majority of investors.

In reality it is not the low yield of Treasuries that has been unusual but the near zero yield of cash, which rarely occurs. Since all asset classes price relative to cash, low yields impact everything. They are just more easily observable in low Treasury yields. This is a crucial insight: low cash yields lower the total returns of all asset classes since they are all priced relative to cash. The excess returns should be your focus, and they remain unchanged as a result of low-yielding cash. If you observe every asset class relative to cash as described in an earlier chapter, then this thought process should make sense. This point is most obvious when considering Treasuries because of the close similarity between this asset class and cash.

Another argument against holding Treasuries in a portfolio is that the yield is said to be artificially low because the Fed is printing money and buying these bonds. The thinking goes that this is not normal and is in effect artificially depressing rates far below where they would be were it not for the government's manipulation. And, once the Fed stops doing this, rates are surely going to rise. Thus, in today's unique environment, the argument continues, it is not just how the future transpires relative to expectations but the role government plays in the process—it is not a free market, but one that is being controlled by a noneconomic participant. Many experts have proposed this line of thinking.

However, the flaw in this perspective is that it fails to fully appreciate the reasons for the Fed's involvement. Think of our discussion in the first chapter. The deepest economic collapse since the Great Depression forced the Fed to first lower interest rates to zero and then engage in quantitative easing (or printing money) to push longer-term interest rates lower and inject money into the economy. The last time this was done to this degree was during the Great Depression, when similar economic conditions existed. In other words, interest rates are low because the economy is extremely depressed, which is the type of environment in which Treasuries are biased to do well (and they have).

In fact, it is debatable whether interest rates would be higher or lower if the Fed were to stop buying Treasuries. The first few times Treasury purchases ceased shortly after 2009, interest rates actually fell even lower because the lack of printing of currency caused the economy to weaken, which caused rates to fall further. The forces of the economic environment outweighed the reduced buying by the Fed to force rates even lower. Conversely, each time the Fed started to buy bonds, rates actually rose because the economy strengthened. Thus, the answer to the question of whether rates are artificially low is unclear. Had the Fed never bought a single Treasury bond interest rates might be significantly lower than current levels because of the probability of an economic collapse. Perhaps interest rates are artificially high! Consider, for instance, that several European countries have interest rates lower than those in the United States even though the ECB, as of this writing, has printed far less than the Fed.

Major Flaw #2: Long-Term Treasuries Can Deliver Sizable Gains over Shorter Periods

Please note that in this section when I refer to owning long-term Treasuries, I am suggesting maintaining a constant duration to these bonds rather than buying a bond and holding it to maturity. This is an important distinction. If you buy a 10-year Treasury bond, for example, and you hold it until it matures, then the return you will earn is known at the time of your purchase. It will simply be the yield to maturity of the bond. This is the return that most investors think about when they consider investing in Treasury bonds. This logic may sound intuitive because when you analyze the potential return of a bond it seems to make sense to look at the yield it offers plus a return of your principal. From this perspective, a low yielding Treasury bond would understandably look quite unappealing.

However, if instead you buy that same 10-year bond today and then after a year sell it and buy another 10-year bond and continue the process indefinitely, then you will maintain a constant long-maturity Treasury bond. The return stream of this portfolio may be different from that in the first example when the bond is held to maturity, depending on the economic environment.

When considering Treasuries, most investors are concerned that the potential upside is limited when the yield is low. Many are also concerned that there is significant risk of loss because rising interest rates means that Treasuries will lose money. These commonly held views are simply not true when considering the excess returns above cash. We already know the return of cash is low, but this reality lowers the returns of all asset classes, not just Treasuries. The focus should be on excess returns above cash, as I've reiterated multiple times.

The excess return of Treasuries, like other asset classes, is based on how the future transpires versus what was discounted. If interest rates are priced to rise rapidly and they actually fall, then significant returns can be expected. This is because of the huge mismatch between what happened and what was anticipated to occur. You can see that when nearly everyone expects a certain outcome, the pricing in of that eventuality actually creates an opportunity for significant outperformance because of the extreme view. On the other hand, if few expect rates to rise and they do rise because of the shifting economic conditions, then that would lead to underperformance in Treasuries. Treasury outperformance versus cash is possible, then, even with low starting yields.

There is one condition, however: To achieve high returns investors must own longer-duration bonds. Duration is key. It is duration that can produce the high returns and it is duration that helps build balance. Investors have been reducing duration because they are afraid of losing money. Instead they should be increasing duration, not because they expected interest rates to fall, but to improve the balance in the portfolio. If rates happened to rise more than expected, then other segments of the portfolio could have benefited (such as equities, if rates rose because the economy was strong). If rates fell (as they did), then the Treasuries would have appreciated enough to offset the losses in the other asset classes. This critical point will be fully explored later in this chapter and in the subsequent discussion about the makeup of the balanced portfolio at the end of the book. The key argument I am trying to make at this point of the discussion is that you can achieve very good excess returns even if the starting yield is low—if you maintain long duration.

Once again, recent experience provides a helpful example of the dynamic described above. The 30-year Treasury yield on June 30, 2011, was 4.4 percent and it closed at 2.9 percent just three months later. The reason it fell so much was because the economy materially weakened unexpectedly during that short time horizon because the Fed stopped buying Treasuries. Since the duration is so long, the excess return during that three-month period was 30.9 percent! The S&P 500 dropped 14.1 percent during that three-month span and investors who didn't own long Treasuries were fully exposed and likely lost significant capital.

What about the consensus view among experts that going forward it is highly unlikely that interest rates will fall again? The problem with this argument is the simple fact that the consensus view has been an extremely poor indicator of future returns time and again. Consider that the three best years in the history of the Treasury market all occurred at a time when Treasuries were most out of favor (+32 percent excess returns in 1982 after an 18-year run of rising interest rates, +39 percent in 2008, and +35 percent in 2011 when interest rates were widely considered to be too low). Not only did Treasuries outperform consensus expectations, but they emphatically delivered record returns!

What about the argument that bond yields do not sufficiently compensate investors against inflation? The current yield may be less than expected inflation, but that does not necessarily mean that the total return (yield plus principal gains) will be less than actual inflation. In terms of total return, the example above clearly demonstrates that with enough duration, the total return can far exceed inflation. Furthermore, we do not yet know what inflation is going to be over time. It may be much higher or it may be much lower (or even negative as it was for a moment in 2008). The key consideration is whether the future plays out as expected. Far too often, investors are guilty of placing too much confidence in their ability to accurately predict the future despite having a subpar track record (selective memory in this area tends to obscure reality).

Major Flaw #3: Cutting Treasury Exposure Reduces Balance and Makes Portfolios More Risky

Many investors have been cutting their exposure to Treasuries as a response to their concerns about limited upside and big downside risks in this asset class. The act of reducing Treasury exposure can take two main forms, both of which have a similar impact on the total portfolio (as you will see shortly).

First, you might cut the allocation to Treasuries to add other asset classes. Some investors have tried to replace Treasuries with bonds of lower credit quality to increase yield and decrease exposure to what they view as inevitably rising interest rates. The problem with this approach is that a bond with a lower credit quality has a different economic bias than Treasuries. This makes sense because Treasuries have virtually no credit risk, while bonds of other issuers do have varying degrees of risk of default. During weak economic periods the general risk of default rises and therefore adversely impacts lower quality bonds. On the other hand, Treasuries thrive in such an environment because of the flight to quality. In this way, Treasuries are unique securities and there are very few, if any, true substitutes (within the United States at least; of course you can always buy high quality sovereign bonds overseas).

A second way to reduce exposure to Treasuries is to shorten the duration of your Treasury holdings. The thinking is that the shorter the duration, the less interest-rate sensitive the bonds. And since interest rates are expected to rise, reducing duration seems like a reasonable reaction to this problem. It is true that shortening the duration of the Treasury holdings reduces volatility, but more importantly, it also negatively impacts the effectiveness of these holdings. What if rates actually fall instead of rise, or if they don't rise as much as everyone expects? What economic environments would those outcomes likely involve, and what would be the consequences to your portfolio? These are crucial questions that ought to be part of the thought process. Table 5.1 summarizes the changes investors have made in response to concerns about low interest rates and their corresponding impacts on the portfolio.

Table 5.1 Fear of Rising Rates Has Led Investors to ⋯

| Action | Impact | Because |

| Cut Treasury allocation | Underperform during falling growth | Other bonds don't do as well during falling growth |

| Reduce Treasury duration | Underperform during falling growth | Shorter duration Treasuries don't go up as much during falling growth |

We can test the conceptual linkages described in Table 5.1 by comparing the actual returns of the various substitutes for Treasuries during the period from October 2007 (when interest rates first fell to theoretically low levels) to December 2013 (when this book was written). By analyzing how each conventional solution to low interest rates behaved during various environments, we can gain insight into the diversification attributes of each asset class. When you look at the data, try to focus on how each market segment performed when the stock market was going up or down: How did Treasuries do when equities were performing well and how did they do when equities experienced declines? How did shorter-term bonds and lower quality fixed income perform during similar environments? The correlation between asset classes is a critical part of building a balanced portfolio, so the intent here is to demonstrate performance using recent examples of the types of relationships that you might expect.

The results are presented in Table 5.2. The table divides the time frame since 2007 into bull and bear market phases of the stock market, which mostly correspond to strong and weak economic growth cycles, respectively (since inflation has been relatively stable during this period). In addition to long-term Treasuries, the returns of three other asset classes are compared to equity returns during each cycle. Intermediate bonds and cash represent the strategy of reducing bond market duration to protect against rising interest rates. High-yield bonds offer a higher yield and theoretically better downside protection against rising interest rates.

Table 5.2 The Diversification Benefits of Treasuries: Excess Returns during Equity Bull and Bear Markets since 2007

| Shorter Duration | Higher Yield | |||||

| Equity Market Highs and Lows | Period | Equities | Long-Term Treasuries | Intermediate Bonds | Cash | High-Yield Bonds |

| Peak to Trough | 10/07–3/09 | –58.2% | 30.4% | 7.2% | 2.9% | –29.5% |

| Trough to Peak | 3/09–4/10 | 84.2% | –12.9% | 9.5% | 0.2% | 72.4% |

| Peak to Trough | 4/10–7/10 | –15.6% | 13.5% | 3.0% | 0.0% | –2.1% |

| Trough to Peak | 7/10–4/11 | 35.5% | –4.9% | 3.0% | 0.1% | 16.1% |

| Peak to Trough | 4/11–10/11 | –18.6% | 36.7% | 5.4% | 0.0% | –7.5% |

| Trough to Peak | 10/11–4/12 | 30.5% | –8.6% | 1.0% | 0.0% | 12.6% |

| Peak to Trough | 4/12–6/12 | –9.6% | 17.5% | 2.2% | 0.0% | –0.7% |

| Trough to Peak | 6/12–12/13 | 49.7% | –19.9% | –0.5% | 0.1% | 18.9% |

| Total Period | 10/07–12/13 | 36.1% | 44.1% | 34.8% | 3.5% | 69.8% |

Source: Bloomberg.

All returns cumulative.

Indexes used are as follows: equities (S&P 500), long treasuries (Citigroup US 30 Year Treasury), intermediate bonds (Barclays Aggregate Bond), cash (3 month Treasury repo rate), and high yield (US High Yield Master II).

Specific time periods used are as follows: 10/9/07–3/9/09, 3/9/09–4/23/10, 4/23/10–7/2/10, 7/2/10–4/29/11, 4/29/11–10/3/11, 10/3/11–4/2/12, 4/2/12–6/1/12, 6/1/12–12/31/13.

These represent peak to trough and trough to peak periods for the S&P 500 Index since October 2007.

None of the popular substitutes for Treasuries offered similar upside during periods that equities suffered losses. The critical lesson to draw from the analysis in Table 5.2 is an appreciation of why the return patterns of the recent past materialized. The economy underperformed expectations and therefore long-term Treasuries, which are biased to outperform in such periods, soared in value. It certainly could have gone the other way. In fact, there were periods during which Treasuries did poorly during this great run. Of course, equity gains during those times more than offset the underperformance in Treasuries.

Clearly, of all the bond substitutes—intermediate-term diversified bonds, cash (both of which are proxies for shorter-duration bonds), and high-yield fixed income—Treasuries proved to be the best diversifier. This analysis has nothing to do with the fact that Treasuries outperformed most of the rest (high-yield bonds ended with better absolute performance, although the pattern of returns generally matched those of equities). Indeed, the opposite result would have yielded the same conclusion. The returns shown in Table 5.2 should be expected because of the environmental bias of this crucial asset class. Intermediate diversified bonds, although they are of high quality, do not have sufficient volatility to materially help the portfolio during economic weakness. Cash and low-duration fixed income strategies don't move enough to make a difference. High-yield bonds, which are more credit-sensitive than interest rate-sensitive, predictably tend to correlate with the ups and downs of the stock market. All three commonly used bond alternatives offer inferior diversification benefits when compared to long-term Treasuries.

The three major oversights that I just covered help demonstrate the flaws in conventional thinking as it relates to the Treasury asset class. In the rest of this chapter I reintroduce Treasuries using a balanced portfolio perspective. As you will read, the focus will not be on the future expected return of Treasuries as is the conventional approach.

Considering Treasuries through a Balanced Portfolio Perspective

Treasuries, despite their low yield, still play an important role in well-balanced portfolios. In order to more fully appreciate this conclusion, I will cover the economic bias of Treasuries in terms of growth and inflation and the volatility of long-term Treasuries. You have already seen how these two factors represent the key inputs in the asset allocation process of a balanced portfolio, so a continuation of a similar thought process will now be applied to Treasuries.

Economic Bias: Treasuries Favor Falling Growth

Weak growth benefits Treasuries because of the increasing likelihood of falling interest rates. This occurs because a weakening economic environment produces a reaction by the central bank to consider lowering interest rates to encourage borrowing to spur economic growth. When growth unexpectedly declines, it results in a move by the Fed that had not been anticipated by the market since the falling growth itself had not been expected. As a consequence, interest rates decline because cash rates suddenly are discounted to rise less than previously anticipated.

Declining interest rates are great for Treasuries because the bonds you own have a fixed interest rate. If prevailing rates are lower than those discounted at the time of your purchase, then the higher coupon of your bond relative to market rates makes your bond a more attractive investment. Consequently, the price rises to reflect the new reality of lower interest rates as this gradually becomes apparent to the market.

Moreover, Treasuries tend to do well during weakening growth periods because of a flight to quality during adverse economic environments. When bad things happen to the economy, it seems reasonable that investors would react by becoming more cautious and risk averse. Treasuries, which have no credit risk, all of a sudden become more attractive investments because the focus shifts from maximizing returns to protecting capital. The high-quality bias of Treasuries attracts frightened investors who are seeking a safe place for their money.

Within this context you might better appreciate how low interest rates can go even lower. All it takes is for economic growth to underperform what is already discounted. Since growth underperforms expectations roughly half the time from a historical standpoint, it makes sense that the odds of low rates dropping are similar to the odds of them rising (even with low starting yields).

Economic Bias: Falling Inflation Benefit to Treasuries

Lower inflation also benefits bond prices. As I expressed in the opening chapter, the Fed attempts to keep inflation at bay by raising interest rates to deter borrowing when inflation is too high and lowering rates to stimulate debt growth when inflation is too low. Each incremental change in inflation produces an expectation of its future path. How that expectation relates to what has already been discounted in the original price is then reflected in the current price. If inflation falls more than expected, then that leads to a greater likelihood of the Fed lowering short-term interest rates. This new discovery then feeds into the increased probability of lower future long-term interest rates, which benefits Treasury prices.

Important Distinction: Deflation versus Falling Inflation

One quick note on deflation needs to be pointed out. Inflation has been the natural state of the economy during nearly all of U.S. history. Inflation means that prices are rising. Falling inflation implies that prices are rising less than they were before: That is, the rate of price increases has declined, although prices are still rising. This scenario is called disinflation. An important distinction needs to be made between disinflation and deflation, the latter of which means a period in which prices are actually falling.

Deflation is not good for an economy, even though you might argue that you would prefer to pay less for what you buy. The reason deflation is such a negative outcome is because of the vicious cycle to which it normally leads. In the first chapter I described the economic machine as a system that vitally depends on increased spending. The more spending there is, the better the economy, since spending improves incomes and provides for a virtuous, self-reinforcing cycle. When there is deflation, people tend to reduce their spending. This is particularly true when deflation becomes entrenched for an extended period of time. Imagine if you anticipated that prices would be lower next month than present levels. Wouldn't you most likely wait to make that big ticket purchase at the lower price? A short-term drop in overall prices of goods and services is fine because spending would likely continue, if not pick up, as consumers take advantage of sale prices. However, the longer deflationary conditions exist, the greater the negative impact on spending patterns as people start to realize that they would benefit from postponing their purchases. The problem with this reaction is when the majority simultaneously cut spending it results in falling incomes, which then leads to reduced spending. This negative spiral is difficult to break and can lead an economy into a major prolonged depression. The Japanese economy since the early 1990s provides a prime example of this dynamic, as does the U.S. Great Depression in the early 1930s.

The severe negative consequences of deflation—in contrast to the benefits of falling inflation—are precisely why central banks are so focused on avoiding this economic outcome. When inflation rates fall too low, there is great incentive for central banks to lower interest rates to stimulate more borrowing in order to improve growth and increase the inflation rate. Central banks, generally speaking, prefer for inflation rates not to hover too close to zero for long. Keep in mind that deflation is historically quite rare, mainly because of the central bank's ability and willingness to avoid it at any cost. Further, the recent Japanese and European deflationary periods offer central banks vivid reminders of the severe social, political, and economic costs of such dire circumstances.

This background about deflation relates to this section of the book because this particular economic environment should be examined on its own. It does not fit cleanly into the rising-falling growth and rising-falling inflation construct described earlier. Like the economic shock that comes from deflation, the impact of this environment on asset class returns can also be drastic. Stock prices collapse an average of 90 percent and in many instances it leads to widespread bankruptcies. Commodities and inflation-linked bonds, both of which are pro inflation investments, generally lose significant value as well. In fact, few asset classes hold their value as a mad rush into cash often dominates during such periods. Treasury bonds may provide a safe haven since their prices are most directly impacted by shifts in interest rates. Deflation is normally met by a drastic cut in rates in an effort to promote borrowing and spending.

Therefore, Treasuries carry with them some deflation protection in addition to the falling inflation bias. Deflation does not occur frequently, so don't overvalue this characteristic. That said, if it does occur, you would be very glad that you own some long-term Treasuries. Think of it as insurance: You rarely need it, but it is prudent to keep it just in case. Given where we are in the long-term debt cycle, holding some deflation protection may not be such a bad idea in the present economic climate.

Putting It Together: Falling Growth and Falling Inflation (and Deflation) Economic Bias

As described above, lower interest rates benefit bond prices. More precisely, it is the future path of cash rates that influences bond prices. This is because the bond yield at various maturities from short-term to long-term merely reflects the discounted changes in cash rates. Since the Fed controls cash rates and the Fed responds to changes in the economic environment (in terms of growth and inflation) by adjusting cash rates, then these economic shifts together impact discounted cash rates. Changes in cash rates then impact longer-term interest rates, which directly affect Treasury bond prices.

Table 5.3 provides historical data that supports these cause-effect linkages. The rare deflationary periods that we've experienced have been bundled with falling inflation economic climates in this table.

Table 5.3 Annualized Long-Term Treasuries Excess Returns by Economic Environment (1927–2013)

| Average Excess Return for All Periods (Good and Bad) | Good Environment (Avg. Excess Return) | Bad Environment (Avg. Excess Return) |

| 1.4% | Falling growth (5.5%) | Rising inflation (0.2%) |

| Falling inflation (2.6%) | Rising growth (–3.0%) |

As you might expect, at 1.4 percent the historical average excess return above cash is not very high. Treasuries have the same credit risk as cash, so investors in long-term Treasuries only receive compensation for the interest rate risk that is taken. As is the case with equities, the difference in returns by economic environment is meaningful. During falling growth periods the excess return of Treasuries has averaged 5.5 percent per year. This is a very strong average return that is nearly identical to the 5.6 percent equity average excess return (for all periods). Considering that about half the time growth is falling relative to expectations, it is easy to see the benefits of owning Treasuries as part of a balanced portfolio.

Of course, the opposite environment of rising growth has historically been very bad for Treasuries, with an average excess return of –3.0 percent. Predictably, Treasuries benefit from falling inflation and underperform during periods of rising inflation, as demonstrated in Table 5.3.

Figure 5.2 provides similar data for longer-term rolling 10-year periods. Notice that the good times occurred during predictable economic climates, as did the bad environments.

Figure 5.2 10-Year Rolling Long-Term Treasuries Excess Returns versus Growth and Inflation

The Benefits of Higher-Volatility Treasuries

One very important and somewhat counterintuitive point about the returns in Table 5.3 needs to be reinforced. The only reason the returns diverge materially between the good and bad periods is because we are using long-duration Treasuries. Shorter-duration Treasuries would share exactly the same environmental bias as longer-term Treasuries. In fact, the excess returns above cash are nearly identical. However, the returns during good environments and bad environments would not be too different. Good periods would outperform the average excess return by a little bit and bad environments would produce slight underperformance. This is simply because longer-duration bonds have more volatility than short-term bonds. More volatility means that the return pattern will fluctuate more, which leads to the wider divergence in returns during good and bad economic climates.

From a conventional perspective, when you have two asset classes that produce the same returns you would always select the one that has less risk or lower volatility. Why get the same return for more risk? However, from a balanced portfolio viewpoint, you do not make asset allocation decisions based on the same criteria. Instead the emphasis is on identifying the economic bias of each asset class and determining its volatility. As is apparent from Table 5.3, the reason more volatility is preferred over less volatility (and therefore long-duration instead of short-duration Treasuries) is because of the better returns when you need them. This is the whole idea behind building balance. You focus less on each individual asset class and more on how it fits within the bigger picture. Each asset class is part of a team and serves a bigger purpose.

The Role of Treasuries in the Balanced Portfolio

Treasuries do well when growth comes in below expectations, when inflation falls below consensus views, or when both conditions are present, as shown in Figure 5.3.

Figure 5.3 The Economic Bias of Treasuries

Economic growth has historically underperformed about half the time. This observation has been true since 1927 and is very likely to persist looking forward. This is a reasonable outcome because what really matters is how future economic conditions play out versus what had already been discounted. The consensus view about future growth is factored into today's price of Treasuries (as well as equities, commodities, TIPS, and all other asset classes).

It makes sense that the consensus, or average, view is wrong about half the time for two main reasons. First, the middle point of a data set means that half the outcomes fall below and half above that point. Second, the consensus view generally represents an extrapolation of the recent past into the near future. Most people expect the next 6 to 12 months to resemble the last 6 to 12 months. Few try to anticipate inflection points, and even fewer foresee major shifts before the fact.

The same can be said about inflation. Roughly half the time what transpires is above what had been discounted and the other half below. Importantly, this range of outcomes exists whether interest rates are high or low. Everyone can easily observe the level of current interest rates and therefore factors this into expectations of future growth and inflation.

This background is repeated here because it is fundamental to describing the important role of Treasuries in the balanced portfolio. The same background is also crucial for establishing the importance of each asset class within the context of a truly balanced asset allocation.

Importantly, since 2007 short-term Treasuries have not enjoyed success similar to long-term Treasuries. This is because shorter duration reduces volatility both ways. When rates rise more than discounted, then long duration hurts more, but when rates don't rise as fast as expected, then long duration helps more. One core idea behind the concept of maintaining a well-balanced portfolio is that you do not have to correctly guess which way it is going to go. If rates move against you, then other parts of the portfolio are biased to outperform during that environment. If rates move favorably for Treasuries, then that is likely because of an adverse economic environment that would simultaneously cause other parts of the balanced portfolio to underperform. Therefore, if you don't maintain sufficient duration, then you leave the portfolio exposed to environments during which Treasuries are biased to outperform. If the economy suddenly weakens and you don't have sufficient duration in your Treasuries, then this part of the portfolio would not go up enough to offset underperformance elsewhere.

Each asset class in the balanced portfolio fills a specific role because it serves to cover certain economic environments. If one of the asset classes were removed from the efficient starting point, then the portfolio would naturally be exposed to the economic environment that had been previously covered by that asset class.

The two economic environments that Treasuries cover are weak growth and falling inflation (or deflation). Weak growth is the more important of the two, since most portfolios are already underweight weak growth assets (either because of a lower quality bias in bonds, smaller total allocation to Treasuries, or a shorter duration). In other words, if long-term Treasuries are reduced from the efficient mix, then there is effectively a big bet that the economy will not underperform expectations. Remember that economic growth is falling about half the time, since it is relative to market discounted conditions. If you underweight Treasuries and the economy does weaken, then overall portfolio underperformance is likely to result because of the imbalance in the portfolio due to the underweight to Treasuries.

Rather than focusing on how Treasuries may perform if interest rates rise (as is nearly universally the concern), you should view the role of this important asset class within the framework of a balanced portfolio efficient mix. Viewed through this lens, you would be less worried about the performance during rising interest rate environments, since other segments in the balanced portfolio are biased to do well during that period (namely, commodities or TIPS if rates rise due to rising inflation, or commodities and equities if rates rise due to rising growth; you'll see this as we cover additional asset classes). Another question that will become apparent when thinking in balanced portfolio terms is what would happen to the portfolio if interest rates fall and Treasuries are missing? Even if rates are low, they can certainly go lower (as you've seen not just recently but throughout the history of financial markets).

Summary

Of all the potential economic environments that you would likely want to cover in your portfolio, it is the falling growth scenario that is perhaps the most significant. The worst equity bear markets in history occurred during the weakest economic environments, and more accurately, during the periods in which most investors had expected continued good times but were suddenly blindsided by unexpected downturns (i.e., 2008–2009, 2000–2002, 1973–1974, 1929–1932, etc.).

With this understanding, the recent moves by investors to cut exposure to Treasuries in favor of lower quality, higher yielding bonds and to drastically reduce duration can be reexamined. It may be more apparent now why these actions have actually increased the risk in the portfolio by making the allocation less diversified. Nearly everyone is afraid of rising interest rates. Yes, there is risk of loss in Treasuries if interest rates rise (as they did in 2013), but there is also risk of loss in the rest of the portfolio if interest rates fall (usually because of a weakening economic environment). This became apparent in 2008 and 2011. The most important message to remember is that it is far better to hedge the interest rate risk by adding asset classes that are biased to do well during environments in which rates rise than to significantly reduce Treasury exposure.

Putting it all together, it should be understandable why a core allocation to long-term Treasuries should have a permanent place in your balanced portfolio. Furthermore, the low yield should not deter you from owning this asset class because of the critical role it plays within the foundation of a well-balanced mix of asset classes.