Chapter 7

Owning Commodities in a Balanced Portfolio

Assets that hedge against the risks of rising inflation are hard to come by. The traditional asset classes of stocks and bonds are both biased to outperform during periods of falling inflation. Consequently, traditional portfolios—which are mostly invested in stocks and bonds—are highly exposed to environments in which inflation is rising. These types of portfolios tend to perform extremely poorly during climates dominated by rising inflation, as should be expected given the predictable return patterns of these asset classes in terms of their economic bias.

In the last chapter I discussed how the inflation protection TIPS offer is a benefit to portfolios. TIPS provide direct inflation protection because returns to TIPS holders are inflation-adjusted. Commodities represent another asset class for your portfolio that covers the rising-inflation environment category. In this chapter I will first explain how commodities investments work, since the investment structure is different from the asset classes previously discussed. Next, commodities will be viewed through the conventional lens and the flaws in this thinking will be exposed. Finally, I will walk you through how to analyze commodities through a balanced portfolio perspective to help you appreciate how this asset class fits within a total balanced portfolio framework.

What Are Commodities Investments?

There are various commodities in which you can invest. A short list of the main commodities includes oil, gas, industrial metals (copper, aluminum, etc.), precious metals (gold, silver, etc.), agricultural commodities (soybeans, corn, sugar, etc.), and livestock (cattle, hogs, etc.). Commodities are very different investments from mainstream stocks and bonds. Unlike equities and fixed income securities, commodities do not generate income or pay dividends or interest. The return you receive is based solely on the price change of the underlying commodity (or, more precisely, the futures price as will be discussed later in this chapter). If the price rises over time you earn a positive return, and vice versa.

The other big difference between this asset class and the others we have covered thus far is that commodities are real assets. Stocks, bonds, TIPS and most other asset classes, in contrast, are financial assets. A real asset is something that is tangible and that you can touch; a financial asset is merely a contract that reflects a claim in an underlying asset. The reason I make a distinction between real and financial assets is because this attribute is actually one of the main reasons why commodities tend to be better inflation hedges. The supply of commodities cannot easily be increased with financial engineering. It takes time for the supply to change as production of each commodity is adjusted based on underlying demand and the cost of production. A relatively fixed supply generally results in price changes stemming from shifts in demand for the commodities. Changes in demand come from the economic cycles that you are trying to diversify against.

Due to the tangible nature of commodities, investing in this market segment is unlike investing in the other asset classes that I have covered. Holding a stock or a bond is easy because buying and selling is as simple as a click of a button. No physical asset needs to be stored because stocks and bonds are financial assets that only require a computer entry or certificate of ownership. The stock or bond appears on your monthly statement and can be easily tracked. Buying a commodity is quite different since you cannot effortlessly store a commodity such as oil or cattle.

There are generally two ways to invest in commodities without having to deal with the administrative burden and cost of holding the physical asset. First, you can buy the stocks of the corporations that invest in commodities such as metals miners or oil producers. The logic is that as the price of the commodities rise, the profits of these companies also improve and therefore lead to higher stock prices. Since stocks are liquid investments, you can gain exposure to commodity prices with little effort and none of the cumbersome restrictions that come with holding physical commodities. The challenge with this approach is that the stock price may not be highly correlated with the underlying commodity price. The companies may be mismanaged or they may hedge out the price risk of the commodity, thereby giving up the upside price movement. Another way to say this is that by investing in commodity stocks, you are taking on additional stock market risk on top of the risk of commodity price changes. Therefore, you may have periods during which the commodity price goes up but the stock price falls, and vice versa. Recall that the key to building a balanced portfolio is to ensure that the various economic environments are adequately covered. Thus, it is imperative that your commodity allocation tracks the price of the underlying commodities as closely as possible. For these reasons commodity stocks may not be an ideal fit for the balanced portfolio.

Entering into a futures contract with another party for the price of the commodity is probably a cleaner approach to investing in commodities, and is the strategy used in this book. This process in effect converts this real asset into a financial asset, just like the rest of the asset classes. This conversion provides increased liquidity and tighter correlation with the underlying commodity price. The way these agreements work is that you invest in a contract with another party in which you promise to pay a fixed price at a future date for a specific commodity. This price, called the futures price, may be higher or lower than the current price of that commodity, termed the spot price. For example, if the spot price of oil is $100 per barrel today, the price you might agree to pay for a barrel of oil (in say, three months) may be $102. With this agreement, you have the obligation to pay $102 for a barrel of oil in three months and the counterparty is required to physically deliver the barrel of oil to you. Since investors in commodities rarely want to actually receive the barrel of oil (and the other party normally doesn't want to deliver it to you), nearly all commodities futures contracts are settled before the predetermined delivery date. The settlement terms are simply the difference between the then-current price and the futures price that had been established at the inception of the contract. In the example above, if the price of oil is $105, then the winning party who purchased the commodity future earns $3 ($105 current price minus $102 agreed-upon futures price) and the losing side that sold it pays $3. It is a zero sum game because the gains of one party are equal to the losses of the other.

In practice, entering these futures contracts is far simpler than it may seem at first. You do not actually have to go find someone who will take the other side and hire an attorney to draft the documents. These contracts are actively traded in highly liquid, regulated exchanges that are not too different from the stock and bond markets. Long-term investors, short-term speculators, and those who are looking to hedge themselves against adverse commodity price movements trade in these markets. The hedgers are typically commodity producers who often prefer to know today the price they are going to sell the commodity for in the future. These market participants can take both sides of the trade and together create sufficient buyers and sellers of commodity futures contracts to establish a fluid tradable market.

The main goal with commodities investing is to gain exposure to a diversified basket of the price of these items in order to achieve the target of hedging against inflation risk. A balanced basket can easily be purchased via a commodities index fund that has a specific, predetermined weight to a large number of commodities in order to provide sufficient diversification to investors. This also takes the guesswork out of picking the right commodities to own.

The Conventional View of Commodities

Most conventional portfolios include a very small proportion, if any, of commodities investments. To better understand why this is the case, it will be helpful to look at the attributes of commodities through a conventional lens. The conventional approach to assessing the attractiveness of most asset classes is to review their historical returns to determine whether they offer upside potential. This expected return might also be compared to expected risk to assess the return-to-risk ratio. A question that is often asked is whether the investment provides a compelling return for the risk taken. Asset classes that offer higher returns per unit of risk are deemed to be the most attractive, and those with low expected returns and high risk are considered to be unattractive. The conventional logic follows that if the goal of a portfolio is to have high returns with low risk, then a collection of asset classes that share the same attributes would efficiently accomplish this objective.

When viewed through this lens, the commodities asset class does not look very appealing. It has historically produced low excess returns relative to its high volatility. Table 7.1 summarizes the average historical excess returns and standard deviation (or risk) of each of the four key asset classes I have covered.

Table 7.1 Returns and Risk of the Major Asset Classes (1927–2013)

From a conventional standpoint, commodities jump out on this list. This asset class is one of the riskiest investments because of its high standard deviation, but its average excess return is one of the lowest. The risk is similar to that of equities, but the long-term return is like that of bonds. Low return and high risk: why would anyone want to own this asset class? Consequently, the conventional allocation to commodities tends to be very low.

Such an outcome seems to make sense when approaching the asset allocation decision within the conventional framework. Most investors look at each asset class as a stand-alone investment and try to identify those market segments that offer compelling prospective returns with lower risk (which are often based on historical returns). This approach can be contrasted to a balanced portfolio context in which each asset class is examined in terms of its contribution to the total mix rather than its own merits. Thus, some asset classes may be unattractive on their own but warrant inclusion in the portfolio because of the benefits they provide when looking at the bigger picture. In other words, the true diversification benefits of owning commodities are only obvious when looking through a balanced portfolio framework, which depends on reliable cause-effect linkages as opposed to through the traditional lens, which tends to overemphasize historical data (returns, risk, and correlation).

A second drawback to commodities from a conventional perspective is that this particular asset class, unlike many others, contains some structural impediments. First of all, the fact that commodities do not generate income or pay a dividend or interest makes it difficult to calculate their fair value. How would you know what an asset is really worth if it doesn't earn or pay anything? A commodity's value and return is based entirely on what others will pay for it in the future. As a result, this asset class is often missing from the menu for investment portfolios focused on investing in undervalued or cheap asset classes because investors simply cannot determine whether it is a good buy at the current price.

The second structural concern for commodities investments is the potential discrepancy between the price of commodities futures and current (or spot) prices. That is, the price of the actual commodity may rise but the futures price may not follow suit. Thus, by investing in commodities futures you are taking the risk that even if the underlying commodity appreciated in value you may not benefit from the gain.

These two major arguments against commodities stem from using a conventional lens and are overstated. Each of these reasons to avoid commodities contains major flaws that I will explain next.

Major Flaw #1: Low Returns and High Volatility—Why Would I Ever Invest in Commodities?

The bottom-line reason to own commodities is because they are biased to outperform when you really need them to. This holds true even though the average returns over time may be unattractive. A perfect analogy is insurance, which tends to share similar characteristics. Insurance protects you in the event of a disaster (be it a fire, an accident, death, or whatever you are insuring against). If the event you are insuring against doesn't occur, you lose a little by owning insurance, since you have to a pay a premium to stay insured. You can think of commodities in the same way. Even if the total excess return above cash is very low over the long run, you still benefit from owning it because it pays off during periods in which your other assets may be doing poorly (particularly during rising inflation economic climates). The higher the inflation relative to expectations, the more it earns. When considered from this perspective, a low average excess return over time actually makes it even more attractive than insurance. Insurance has a negative return almost all the time and probably a net negative expected return to you over the long run even if it does pay off every now and then (which is precisely why insurance companies exist and are highly profitable). Think of it as insurance that you do not have to pay for. The same rationale applies to TIPS, Treasuries, and every other asset class. Each is there to protect you in a different economic environment. Even stocks are there to protect you against periods of rising growth and falling inflation. You may not feel you need protection against these encouraging periods, but owning stocks protects your portfolio from potential underperformance of the rest of the assets. They all work together and have a specific role. This important concept will be more fully fleshed out later in this chapter when I discuss the role of commodities in a balanced portfolio.

Major Flaw #2: Two Structural Issues—They Pay No Income and Futures Prices Can Diverge from Spot Prices

Commodities produce no income. Your return is based solely on the difference between the price you pay to buy and the price when you sell. Most other asset classes, such as equities, Treasuries, and TIPS, offer interest or dividends in between buying and selling, providing an additional source of returns. Even stocks and bonds that pay no dividends or interest accrue some value while they are being held. Companies earn profits, and if they choose not to pay a dividend they simply reinvest the cash into their businesses. This theoretically adds some value that benefits shareholders. A zero coupon bond that does not pay interest compensates investors with a gradually increasing bond price until it reaches its full par value at maturity.

That commodities produce no income should not dissuade you from including commodities in your balanced portfolio. Due to the pronounced benefits of this asset class's unique characteristics, it is still worthy of a place in a balanced portfolio, regardless of the aforementioned issue. The bottom line is that value is less important than its economic bias. And since there is a scarcity of good inflation hedges, commodities can add value when included in portfolios. The response to this objection will become even more evident when we go through how commodities fit within the context of a balanced portfolio later on.

Another concern involves the unique structure of commodities futures. The apprehension stems from the fact that the spot price of the commodity can rise, but you may still lose money depending on the shape and slope of the futures curve. In reality, you are not investing in the current price of a commodity. Since you are buying a commodity futures contract, you are effectively making a bet on the future price and how that future price may change. Consider the following example: oil today is $100 per barrel and the futures contract three months from today is $102. If you buy the three-month futures contract and during that period oil rises from $100 to $102, then you do not gain anything. This is because you bought a contract for $102 (even though today's price was only $100). Therefore, even though you were right that oil went up $2, you were not able to profit from this foresight since you effectively had to overpay for the investment. The opposite, as argued, is also true. If the futures price is lower than the current price, then that makes investing in commodities a more attractive endeavor. This is the thinking among many market participants.

Although this logic may seem intuitive, it misses a big component of how you should think about investing in commodities futures. Remember that the return you earn from any investment, not just commodities, is based on how the future transpires relative to what had been expected and already factored into the purchase price. I discussed this notion in the section that noted that Treasuries may produce attractive excess returns even though the starting yield is low. The reason for this, as I explained, is that the concern that interest rates may rise (because they are low) is probably already priced into the yield curve. Said differently, longer-term Treasuries offer a higher yield than shorter-term bonds and cash because of the expectation that interest rates are going to rise. This is reflected in an upward sloping yield curve that may be very steep. Your excess return above cash will depend on whether interest rates rise more or less versus what is already discounted. Thus, if everyone expects rates to rise and they actually rise less than the level priced in (but they nonetheless rise), you earn an excess return from holding long-term Treasuries because the increase was less than expected.

A commodities futures curve and the return you ultimately achieve both follow a parallel rationale. If the futures price is higher than the spot price (the current price) that signifies that the market is anticipating that the price will rise between now and the end of the futures contract. If the price rises more than that amount, then you earn a profit. If the price underperforms expectations, then you underperform cash. This is exactly the same dynamic as for Treasuries and stocks, real estate, and any other asset class. It all depends on how the future transpires relative to discounted conditions.

Another simple example involves inverted curves. If the futures curve is inverted that means that the futures price is lower than the spot price. This reflects a market expectation that the price in the future will fall. This may be the case if there is excess supply of the commodity, anticipated economic weakness, or for many other potential reasons. Regardless, if the price falls less than expected you will earn a positive return. For instance, if today's oil price is $100 and the 3-month futures price is $98, even if oil prices fall to $99 you still earn $1.

This is the same thought process that is used to analyze an inverted yield curve for bonds. There are times when a 5-year Treasury may offer a yield that is less than that of a 3-month Treasury. You might reasonably ask why investors would want to tie up their money for five years and be compensated with a lower yield than they can get by locking in their cash for only three months. Going back to the core principles applied above, an inverted yield curve—just like an inverted commodities futures curve—indicates a market expectation that interest rates are going to decline over time. This often occurs because of an expectation of an economic downturn that would cause the Fed to lower interest rates. (You may have heard of the familiar connection between inverted yield curves and recessions: Every time that there's been an inverted yield curve, an economic recession has occurred.) If interest rates actually fall more than is priced in, you would be better off locking in a lower rate for a longer period because you would earn more interest in total (even though your starting interest rate may be lower). In other words, the interest rate for a 3-month Treasury is temporary and when your bond matures you would reinvest your principle in a lower-yielding Treasury. After adding up all the reinvestments over a five-year period, you would have been better off locking in the lower five-year rate in the beginning. Conversely, if rates fall less than is priced in you would outperform with the shorter-term bond. It simply comes down to how the future plays out as compared to what was priced to occur. As a result, the concern that the spot price may be different from the futures price becomes a nonissue.

Considering Commodities through a Balanced Portfolio Perspective

Rather than looking at commodities in terms of how they may perform on their own, you should consider how they fit within the context of the total portfolio. What attributes do they possess that may add value to the total portfolio? To think from this perspective requires you to evaluate commodities with an eye toward the two key factors that influence the total portfolio's returns: its economic bias and its volatility.

Economic Bias: Rising Inflation

Commodities are biased to outperform their average returns during periods dominated by rising inflation. This bias is reasonable and reliable. In fact, commodities are actually part of the inflation calculation. Rising prices in commodities such as energy, metals, and food directly and indirectly lead to broader increases in inflation measurements. The direct impacts on inflation measurements come from the fact that the methodology used to calculate the CPI incorporates changes in the prices of commodities. Meanwhile, indirect effects of rising commodity prices find their way into inflation of other items in the CPI basket because of the fact that these commodities are inputs into the prices of these items. For instance, higher gas prices lead to higher prices for traveling or shipping items because of the increased costs to those companies providing these services. At least a portion of the higher input expenses are typically passed on to consumers via higher prices, which results in higher overall prices for goods and services.

The fact that commodities represent a portion of the input cost of goods and services is another reason there is an inflation link in their returns. As general increased demand for goods and services pushes overall inflation rates higher, the higher demand for the goods and services leads to greater demand for the inputs (the commodities). The higher demand in turn exerts upward pressure on commodity prices. If the demand was greater than expected, then the price generally rises, because the demand originally expected was compared to the original supply to determine the price. This discounted future price is then reflected in the futures curve. Again, your profit depends on whether the future price comes in higher or lower than that price. This outcome will be based on how the future transpires relative to expectations, just as is the case with the other asset classes.

Economic Bias: Rising Growth

Commodities are not only pro-inflation assets, but also are biased to outperform during rising growth environments. As the economy outperforms to the upside, greater commodity demand naturally follows. If I earn more money than I had anticipated, then I am likely to spend a portion of that higher income. Part of that spending will either be directly on commodities (perhaps higher quality food, oil or precious metals) or on other goods and services that will require more commodities to produce. Because economic growth is greater than expected, it is reasonable that the original supply of commodities is insufficient to meet the higher, unexpected demand. This mismatch generally results in upward price pressures. It comes down to expectations versus actual results. Imagine if there was great optimism about the future prospects of the economy: We are living in a boom period and this prosperity is expected to continue. This view would likely result in higher futures prices for commodities, as well as an uptick in the production of commodities. If you are a commodities producer and feel that the economy is trending positively and commodities prices are rising, you will have the incentive to produce more commodities to meet the anticipated growing demand. Such lofty expectations are often not met since the margin of safety has shrunk. Even if the economy performs well, it would have to do better than expected in order to positively impact commodities prices (or stock prices, or the price of any pro-growth asset class). In the case of commodities, changes in both supply and demand lead to price changes and both are directly impacted by expectations of future economic conditions.

Putting It Together: Rising Inflation and Rising Growth

The historical average excess return of a diversified basket of commodities since 1927 is 2 percent per year and the average volatility has been a very high 17 percent, which is slightly less than the volatility of equities. Most importantly, however, during rising inflation periods (favorable times for commodities) the average excess return has been 8.4 percent per year. This represents the second-best asset class return (behind long-term TIPS at 10.7 percent) of the four major asset classes. Since rising inflation periods occur about half the time (relative to expectations), the benefits of owning this asset class should be apparent. The same analysis holds for the other economic environment in which commodities are biased to outperform: rising growth. Commodities have averaged a 7 percent excess return above cash when there is rising growth, which ranks second to equities. The average return of commodities during different economic environments is presented in Table 7.2.

Table 7.2 Annualized Commodities Excess Returns by Economic Environment (1927–2013)

| Average Excess Return for All Periods (Good and Bad) | Good Environment (Avg. Excess Return) | Bad Environment (Avg. Excess Return) |

| 2.0% | Rising inflation (8.4%) | Falling growth (–2.3%) |

| Rising growth (7.0%) | Falling inflation (–4.0%) |

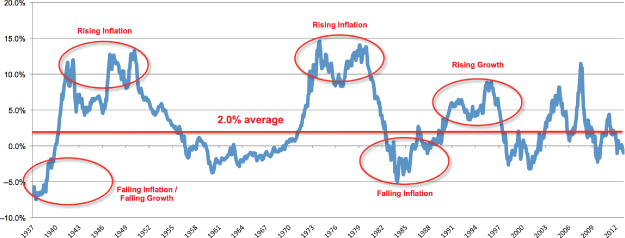

Using rolling 10-year returns, as displayed in Figure 7.1, commodities have outperformed and underperformed as you would expect, given their economic bias.

Figure 7.1 10-Year Rolling Commodities Excess Returns versus Growth and Inflation

The Advantage of the High Volatility of Commodities

Seen from a conventional viewpoint, the high volatility of commodities appears to be a negative attribute. However, when considering how commodities fit within the framework of a balanced portfolio, something remarkable occurs. You will discover that commodities are actually more valuable to the balanced portfolio because they are highly volatile. If they were not volatile, they would provide less of a benefit. This may sound like an exaggeration, but the following example provides support for this highly counterintuitive statement.

To prove this point, I will take an extreme example. Imagine if there were another asset class that offered exactly the same return as commodities but with zero risk or volatility. In other words, this asset class, which I will call no-risk commodities, has returned the same long-term percentage return as regular commodities (2 percent excess returns since 1927) but was able to achieve these results through a perfectly smooth return path. Commodities averaged a 2 percent return per year but had years when they were up by 60 percent and periods during which they were down by 50 percent. On the other hand, the hypothetical no-risk commodities earned 2 percent excess returns by earning 0.17 percent per month every month (which is 2 percent divided by 12) without exception. On its own this looks like a very attractive asset class and would score off the charts using traditional risk-return metrics. You are guaranteed to beat cash by 2 percent every year. You would think that this asset class is far superior to normal commodities.

As it turns out, the opposite is true. To demonstrate this I will compare the long-term average historical return of a balanced portfolio with regular commodities with the same balanced portfolio with our hypothetical no-risk commodities. For the balanced portfolio I have used the allocation that is presented in the final chapters of this book. At this point the makeup of this portfolio is not important. This comparison is presented here to demonstrate the significance of the volatility characteristic of commodities. You just need to know that the percentage of commodities in the two portfolios we are comparing is identical and the only difference is the substitution of the commodities return stream. One portfolio uses regular commodities and the other substitutes no-risk commodities. The goal is to completely isolate the impact of volatility on total portfolio returns.

The balanced portfolio's results are actually worse with no-risk commodities than with regular commodities. In this case, higher volatility is better than lower volatility! The comparison is highlighted in Table 7.3.

Table 7.3 The Balanced Portfolio and Commodity Volatility (1927–2013)

| Average Excess Return | |

| With Regular High-Risk Commodities | 4.3% |

| With Hypothetical No-Risk Commodities | 4.0% |

Does this result make sense from a conceptual standpoint when looking through the balanced portfolio lens? Of course it does. Regardless of the results, my objective is to ensure that you now understand why this result is actually more sensible. As I've covered previously, it is the concepts that stand the test of time as the environment will undoubtedly change in the future and new investment strategies and structures will be introduced. You can take these concepts and apply them to various economic environments and asset classes. The reason this outcome makes sense is because the strong returns arrive when you need them to balance underperformance in other parts of the portfolio. By producing a more stable return stream and by minimizing the losses during the really bad times, the improved overall balance that comes from owning commodities outweighs their individual unappealing return-risk characteristics. In this sense, commodities are the true team player!

The Role of Commodities in a Balanced Portfolio

Commodities are biased to perform better during rising inflation and rising growth economic climates, as depicted in Figure 7.2.

Figure 7.2 Economic Bias of Commodities

Putting the inflation and growth bias together, the role of commodities in a balanced portfolio is to offer upside during these periods to help offset weakness in other asset classes not biased to outperform during these climates. The inflation hedge is crucial because of the lack of great options in this area. This is another reason why you might consider including commodities even though investing in this asset class is not as structurally clean as the others.

Summary

If you approached investing the conventional way by analyzing each asset class on its own and putting together a handful that looked independently attractive, then you would immediately dismiss commodities (as most do). With a line of thinking that emphasizes the balanced portfolio you are better able to assess the attractiveness of each asset class based on its role within the context of a truly balanced portfolio. The change in perspective and approach leads to a completely different outlook, asset allocation, and ultimately, improved long-term results.

This is a very important point because it diffuses many of the arguments you may hear about commodities or other asset classes that may appear unappealing as a stand-alone investment. That the various economic environments are adequately covered is more important to the bottom line than the relative attractiveness of the portfolio's individual parts.