14

Entering New Dimensions

In This Chapter

![]() Placing dimensions in drawings

Placing dimensions in drawings

![]() Choosing a dimensioning method

Choosing a dimensioning method

![]() Creating and modifying your own dimension styles

Creating and modifying your own dimension styles

![]() Adjusting dimension sizes to suit the drawing plot scale

Adjusting dimension sizes to suit the drawing plot scale

![]() Placing and modifying annotative dimensions, including details at other scales

Placing and modifying annotative dimensions, including details at other scales

![]() Modifying dimensions

Modifying dimensions

In drafting, either CAD or manual, dimensions are special text labels with attached lines that, together, clearly indicate the size of something. Although it’s theoretically possible to draw all the pieces of a dimension by using AutoCAD commands, such as Line and mText, dimensioning is such a common drafting task that AutoCAD provides special commands to do the job more efficiently. These dimensioning commands group the parts of each dimension into a convenient, easy-to-edit package, much like a block. In fact, AutoCAD actually produces each dimension as something it calls an anonymous block. We discuss blocks in Chapter 17.

Even better, as you edit an object, by stretching a line, for example, AutoCAD automatically updates the measurement displayed in the dimension text label to indicate the object’s new size. And perhaps best of all, AutoCAD’s annotative dimensions adjust their text height and arrowhead size automatically to suit the annotation scale on the model tab or the viewport scale in a layout. We explain the general principles of annotative objects in Chapters 13 and 15; in this chapter, we take a close look at annotative dimensions.

Adding Dimensions to a Drawing

We start off with an exercise to introduce AutoCAD’s dimensioning functionality by creating linear dimensions that show the horizontal or vertical distance between two endpoints:

1. Start a new drawing, using the acad.dwt template file.

This step creates a drawing that uses imperial units, even if your default installation uses metric. It saves us lazy writers from having to duplicate our instructions for metric users.

2. Use the Line command to draw a non-orthogonal line.

A non-orthogonal line is a segment that’s neither horizontal nor vertical. Make the line about 6 units long, at an angle of about 30 degrees upward to the right.

3. Set a layer that’s appropriate for dimensions as current.

Okay, you started from a blank template, so it doesn’t have specific layers, but we included this step as a gentle reminder. As we discuss in Chapter 9, you normally have dedicated layers for visible edges, hidden edges, text, dimensions, section lines, hatching, and so on.

![]() 4. Start the DimLInear command by clicking the down arrow at the bottom of the Dimension button on the left side of the Annotate tab’s Dimensions panel and click Linear, or type DLI and press Enter.

4. Start the DimLInear command by clicking the down arrow at the bottom of the Dimension button on the left side of the Annotate tab’s Dimensions panel and click Linear, or type DLI and press Enter.

AutoCAD prompts you:

Specify first extension line origin or <select object>:

5. To specify the origin of the first extension line, snap to the lower-left endpoint of the line by using an ENDpoint object snap.

If you don’t have ENDpoint as one of your current running object snaps, specify a single endpoint object snap by holding down the Shift key, right-clicking, and choosing ENDpoint from the menu that appears. (See Chapter 8 for more about object snaps.)

AutoCAD prompts you:

Specify second extension line origin:

You must use object snaps when applying dimensions in order to make later editing work properly.

You must use object snaps when applying dimensions in order to make later editing work properly.

6. To specify the origin of the second extension line, snap to the other endpoint of the line by using an ENDpoint object snap again.

AutoCAD draws a horizontal dimension (the length of the displacement in the left-to-right direction) if you move the crosshairs above or below the line. It draws a vertical dimension (the length of the displacement in the up-and-down direction) if you move the crosshairs to the left or right of the line.

AutoCAD prompts you:

Specify dimension line location or[Mtext/Text/Angle/Horizontal/Vertical/Rotated]:

7. Move the mouse to generate the type of dimension you want — horizontal or vertical — and then click wherever you want to place the dimension line.

AutoCAD draws the dimension.

When you’re specifying the dimension line location, you usually don’t want to object-snap to existing objects. Rather, you want the dimension line and text to sit in a relatively empty part of the drawing rather than have it bump into existing objects. If necessary, temporarily turn off running object snap (for example, click the OSNAP button on the status bar) to avoid snapping the dimension line to an existing object.

When you’re specifying the dimension line location, you usually don’t want to object-snap to existing objects. Rather, you want the dimension line and text to sit in a relatively empty part of the drawing rather than have it bump into existing objects. If necessary, temporarily turn off running object snap (for example, click the OSNAP button on the status bar) to avoid snapping the dimension line to an existing object.

If you want to be able to align subsequent dimension lines easily, turn on Snap mode and set a suitable snap spacing (more easily done than said!) before you pick the point that determines the location of the dimension line. See Chapter 8 for more information about Snap mode. You can also use the DIMSPACE command to select several existing dimensions and then automatically space them equally.

If you want to be able to align subsequent dimension lines easily, turn on Snap mode and set a suitable snap spacing (more easily done than said!) before you pick the point that determines the location of the dimension line. See Chapter 8 for more information about Snap mode. You can also use the DIMSPACE command to select several existing dimensions and then automatically space them equally.

8. Repeat Steps 4–7 to create another linear dimension of the opposite orientation (vertical or horizontal).

9. Click the line to select it.

10. Click one of the grips at an end of the line and drag it around.

The dimensions automatically update, live and in real time, to reflect the current values as you move the mouse.

You probably don’t dimension to four decimal places, use a different font for text, use imperial and metric units, or need to show manufacturing tolerances. Not a problem. AutoCAD controls the look of dimensions by means of dimension styles, just as it controls the look of text with text styles and tables with table styles. In fact, AutoCAD also uses text styles to control the appearance of the text in dimensions. We cover dimension styles in more detail later in this chapter, but suffice it to say that AutoCAD has about 80 variables that can be used to warp dimensions into just about any perversion that your industry or company can imagine.

A Field Guide to Dimensions

AutoCAD provides several types of dimensions and commands for drawing them; most commands are shown in Figure 14-1. These commands are found on the Dimensions panel of the Annotate tab on the Ribbon. If you can’t find the button you want, it’s probably hidden in the drop-down list, under the larger button on the left side of this panel. This panel remembers the last button you used, so at any given time, it may be displaying any one of the following buttons.

Figure 14-1: Examples of dimensioning commands.

In the following list, the three characters (in parentheses) is the shortened command name (command alias) you can also enter:

![]()

![]() Linear — DimLInear (DLI): Indicates the linear extent of an object or the linear distance between two points. Most linear dimensions are either horizontal or vertical, but you can draw dimensions that are rotated to other angles, too.

Linear — DimLInear (DLI): Indicates the linear extent of an object or the linear distance between two points. Most linear dimensions are either horizontal or vertical, but you can draw dimensions that are rotated to other angles, too.

![]()

![]() Aligned — DimAigned (DAL): Similar to linear dimensions, but the dimension line tilts to the same angle as a line drawn through the origin points of its extension lines.

Aligned — DimAigned (DAL): Similar to linear dimensions, but the dimension line tilts to the same angle as a line drawn through the origin points of its extension lines.

You don’t always have to pick points when placing dimensions. Watch the command line; it may ask you to

You don’t always have to pick points when placing dimensions. Watch the command line; it may ask you to

Specify first extension line origin or <select object>:

If you press Enter instead of picking the first point, AutoCAD prompts you to select an object. And when you do, it automatically selects each end of the object for you.

![]() Angle — DimANgle (DAN): Indicates the angular measurement between two lines, the two endpoints of an arc, or two points on a circle. The dimension line appears as an arc that indicates the sweep of the measured angle.

Angle — DimANgle (DAN): Indicates the angular measurement between two lines, the two endpoints of an arc, or two points on a circle. The dimension line appears as an arc that indicates the sweep of the measured angle.

![]() Radial — DimDIameter (DDI), DimRAdius (DRA): A diameter dimension calls out the diameter of a circle or an arc and a radius dimension shows the radius of a circle or an arc. You can position the dimension text inside or outside the curve; refer to Figure 14-1. If you position the text outside the curve, AutoCAD draws (by default) a little cross at the center of the circle or arc. AutoCAD automatically adds the diameter and radius symbols to the appropriate dimension type.

Radial — DimDIameter (DDI), DimRAdius (DRA): A diameter dimension calls out the diameter of a circle or an arc and a radius dimension shows the radius of a circle or an arc. You can position the dimension text inside or outside the curve; refer to Figure 14-1. If you position the text outside the curve, AutoCAD draws (by default) a little cross at the center of the circle or arc. AutoCAD automatically adds the diameter and radius symbols to the appropriate dimension type.

If you’re wondering when you should use which one (because radius and diameter dimensions seem to do the same thing), the convention in most drafting disciplines is to use diameter dimensions for whole circles (for example, a hole) and use radius dimensions for part circles or arcs (for example, a fillet).

If you’re wondering when you should use which one (because radius and diameter dimensions seem to do the same thing), the convention in most drafting disciplines is to use diameter dimensions for whole circles (for example, a hole) and use radius dimensions for part circles or arcs (for example, a fillet).

You can also use DimLInear to dimension a circle or an arc. Trying to pick the endpoints of a circle can keep you busy for several hours, but if you press Enter at the first prompt and then select a circle or an arc, it applies a linear dimension across the diameter.

You can also use DimLInear to dimension a circle or an arc. Trying to pick the endpoints of a circle can keep you busy for several hours, but if you press Enter at the first prompt and then select a circle or an arc, it applies a linear dimension across the diameter.

![]() Arc Lenth — DimARc (DAR): Measures the length of an arc as though it were stretched out straight and then applies a curved dimension line that’s concentric with the arc.

Arc Lenth — DimARc (DAR): Measures the length of an arc as though it were stretched out straight and then applies a curved dimension line that’s concentric with the arc.

![]() Jog — DimJOgged (DJO): When dimensioning arcs, it is standard drafting practice to create a dimension line that starts at the center of the arc and proceeds outward to the arc itself. A problem arises, however, when dimensioning an arc with a very large radius. The center may be at an inconvenient location where the dimension line would interfere with other geometry or, worse, it may be well beyond the edge of the final drawing. DimJOgged neatly solves this problem for you. It works almost exactly like DimARc except that it asks you to specify two extra points. After you select the arc (or circle, strangely enough), it then asks you to specify a center override point and then a location for the jog itself. The resulting dimension line consists of three segments, starting at the center override point: The first and last point to the real center; the middle segment connects the first and last points by putting a jog in the line.

Jog — DimJOgged (DJO): When dimensioning arcs, it is standard drafting practice to create a dimension line that starts at the center of the arc and proceeds outward to the arc itself. A problem arises, however, when dimensioning an arc with a very large radius. The center may be at an inconvenient location where the dimension line would interfere with other geometry or, worse, it may be well beyond the edge of the final drawing. DimJOgged neatly solves this problem for you. It works almost exactly like DimARc except that it asks you to specify two extra points. After you select the arc (or circle, strangely enough), it then asks you to specify a center override point and then a location for the jog itself. The resulting dimension line consists of three segments, starting at the center override point: The first and last point to the real center; the middle segment connects the first and last points by putting a jog in the line.

![]() Ordinate — DimORdinate (DOR): Applies X or Y coordinate values from an origin point. Certain types of mechanical parts can have a great many holes and other features. The drawing would become impossibly cluttered if you were to apply two traditional dimensions to show the X and Y locations of each detail. Common practice in this situation is to use ordinate dimensioning. Each ordinate dimension appears simply as a single extension line and a number showing the X or Y distance from the origin of the drawing or from the origin of the current user coordinate system (UCS), if there is one. (We cover UCSs in Chapter 21.) Normal practice is to specify the lower-left corner of the part as the origin. The X and Y values are usually aligned neatly in a row and column along the edge of the part. There are no dimension lines or arrowheads.

Ordinate — DimORdinate (DOR): Applies X or Y coordinate values from an origin point. Certain types of mechanical parts can have a great many holes and other features. The drawing would become impossibly cluttered if you were to apply two traditional dimensions to show the X and Y locations of each detail. Common practice in this situation is to use ordinate dimensioning. Each ordinate dimension appears simply as a single extension line and a number showing the X or Y distance from the origin of the drawing or from the origin of the current user coordinate system (UCS), if there is one. (We cover UCSs in Chapter 21.) Normal practice is to specify the lower-left corner of the part as the origin. The X and Y values are usually aligned neatly in a row and column along the edge of the part. There are no dimension lines or arrowheads.

Using the quick dimension commands

Three dimensioning commands can help you place multiple dimensions very quickly. They’re found near the middle of the Dimensions panel of the Annotate tab on the Ribbon.

![]()

![]() Continue — DimCOntinue (DCO): Having placed one linear dimension, you can now carry on to place a series of end-to-end dimensions. AutoCAD automatically picks the end of the previous dimension as the start of the next one, so you need to pick the end of only the next one.

Continue — DimCOntinue (DCO): Having placed one linear dimension, you can now carry on to place a series of end-to-end dimensions. AutoCAD automatically picks the end of the previous dimension as the start of the next one, so you need to pick the end of only the next one.

![]()

![]() Base — DimBaseline (DBA): This one works much like DimCOntinue except that AutoCAD selects the start of the previous one as the start of the next one. You thus end up with a series of dimensions, all measuring from a common starting point.

Base — DimBaseline (DBA): This one works much like DimCOntinue except that AutoCAD selects the start of the previous one as the start of the next one. You thus end up with a series of dimensions, all measuring from a common starting point.

Before AutoCAD 2014, DimCOntinue and DimBaseline would use the current dimension style when placing the additional dimensions. Now, by default, they match the style of the selected dimension.

Before AutoCAD 2014, DimCOntinue and DimBaseline would use the current dimension style when placing the additional dimensions. Now, by default, they match the style of the selected dimension.

![]() Quick Dimensions — QDIM: Interestingly, this is one of the few dimensioning commands that doesn’t start with DIMxxx. When you invoke it, it invites you to select objects. The best bet usually is to use one or more window selections (pick from left to right), each of which completely surrounds several objects. Now, whenever you press Enter, AutoCAD automatically applies DimLInear dimensions wherever it can (and you might be surprised at some of those places). It can place dimensions in several formats, including continue, baseline, staggered, ordinate, and several others. For convenience in repeat operations, it remembers the last mode you used.

Quick Dimensions — QDIM: Interestingly, this is one of the few dimensioning commands that doesn’t start with DIMxxx. When you invoke it, it invites you to select objects. The best bet usually is to use one or more window selections (pick from left to right), each of which completely surrounds several objects. Now, whenever you press Enter, AutoCAD automatically applies DimLInear dimensions wherever it can (and you might be surprised at some of those places). It can place dimensions in several formats, including continue, baseline, staggered, ordinate, and several others. For convenience in repeat operations, it remembers the last mode you used.

Opening the Dimension toolbar

As much as we like the Drafting & Annotation workspace and the Ribbon, one task where using the classic interface just might be more efficient is in dimensioning. The classic Dimension toolbar provides access to more dimension tools than the Ribbon, and it does so while maintaining consistent one-click access to each command. With the Ribbon, you may find that it takes a couple of clicks to find to the command you want, and some dimension commands aren’t even there.

Here’s how to display the Dimension toolbar in a Ribbon-based workspace:

1. Click the View tab on the Ribbon.

2. On the User Interface panel, click Toolbars.

AutoCAD displays a menu of loaded customization files. If your system doesn’t have Express Tools installed, or if you’re using AutoCAD LT, you may see only AutoCAD (or AutoCAD LT) on this menu. If you’re working for a large company, you may well see additional custom menus on this list.

3. Click AutoCAD or AutoCAD LT to display a list of classic toolbars.

4. Choose Dimension from the menu.

AutoCAD closes the Toolbars menu, and the classic Dimension toolbar appears, either floating or docked on an edge of the drawing area.

Where, oh where, do my dimensions go?

In this section, we explain where to put dimensions, not where to place them. Huh? Right. We aren’t going to tell you to place dimensions outside the part outline, with smaller ones closer to the part and longer ones farther away, and so on. In this section, we show you the location in the drawing where your dimensions will live. You can choose one of three different methods for dimensioning your drawings:

![]() You can place dimensions in model space by using non-annotative dimensions. This method, the oldest, for many years was the only possible way. We mention it here because you’re bound to encounter many of the millions and millions of existing drawings that were created this way.

You can place dimensions in model space by using non-annotative dimensions. This method, the oldest, for many years was the only possible way. We mention it here because you’re bound to encounter many of the millions and millions of existing drawings that were created this way.

• Advantage: Dimensions are available in model space as you edit the drawing.

• Disadvantage: As with text and hatching, dimension objects have to be scaled to suit the drawing scale. Placing dimensions on details at other scales can get truly ugly. We cover scale factors in Chapters 13 and 15 as well as later in this chapter.

![]() You can place dimensions in paper space. This was introduced as the second-generation method in an attempt to overcome the scaling issue. You can reach from paper space through a layout viewport and snap onto the model space objects. Dimensions remain associative and usually change when the model space objects change. Paper space layouts are discussed in Chapter 12.

You can place dimensions in paper space. This was introduced as the second-generation method in an attempt to overcome the scaling issue. You can reach from paper space through a layout viewport and snap onto the model space objects. Dimensions remain associative and usually change when the model space objects change. Paper space layouts are discussed in Chapter 12.

• Advantage: You don’t need to set a dimension scale factor to suit the drawing scale. The dimension scale factor is always 1:1 because paper space layouts are usually plotted at full size, and the viewport scale sets the model space scale factor.

• Disadvantages: The dimensions aren’t available when editing in model space, so you’re flying blind. In addition, the associative connections between the paper space dimensions and the model space objects are fragile and easily broken. There’s a repair command, but it’s a nuisance to have to use it.

![]() You can place dimensions in model space using annotative dimensions. This is the newest, latest, greatest, and best way to place dimensions. Annotative dimensions automatically size themselves to suit the drawing scale that you choose. We discuss annotative text in Chapter 13, annotative hatching in Chapter 15, and annotative dimensions later in this chapter.

You can place dimensions in model space using annotative dimensions. This is the newest, latest, greatest, and best way to place dimensions. Annotative dimensions automatically size themselves to suit the drawing scale that you choose. We discuss annotative text in Chapter 13, annotative hatching in Chapter 15, and annotative dimensions later in this chapter.

• Advantages: Dimensions are available in model space while you’re drawing and editing, you don’t need to mess with dimension scale factors, and applying dimensions to drawing details that are at a different scale from the main drawing becomes trivial.

• Disadvantage: Annotative dimensions have been slow to catch on because people are stuck in the older ways (“That’s how we’ve always done it!”) and because they don’t understand a couple of subtleties about them that we reveal in Chapter 13. If you’re the first in your office to adopt annotative dimensions, everyone else will hail you as the Great AutoCAD Guru and will pester you to help them learn how to use them.

The Latest Styles in Dimensioning

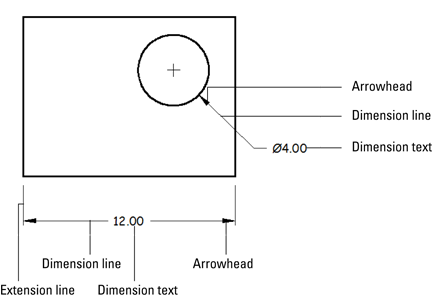

In this section, we discuss how to set the factors that control the format and appearance of dimensions, but we start with a brief anatomy lesson. AutoCAD uses the names shown in Figure 14-2, and described in the following list, to refer to the parts of each dimension:

Figure 14-2: The parts of a dimension.

![]() Dimension text: The numeric value that indicates the true distance or angle between points or lines. Dimension text can also include other information in addition to or instead of the number. For example, you can add a suffix, such as

Dimension text: The numeric value that indicates the true distance or angle between points or lines. Dimension text can also include other information in addition to or instead of the number. For example, you can add a suffix, such as TYP., to indicate that a dimension is typical of several similar configurations; add manufacturing tolerances; and show dual dimensioning in alternate units.

![]() Dimension lines: In linear dimensions, indicate the true distance between points. Angular dimensions have curved dimension lines with the center of the curve at the vertex point of the objects being dimensioned. For radius and diameter dimensions, the dimension line simply points at or through the center of the object being dimensioned. (See Figure 14-1 for examples of these dimension types.)

Dimension lines: In linear dimensions, indicate the true distance between points. Angular dimensions have curved dimension lines with the center of the curve at the vertex point of the objects being dimensioned. For radius and diameter dimensions, the dimension line simply points at or through the center of the object being dimensioned. (See Figure 14-1 for examples of these dimension types.)

![]() Arrowheads: Appear at the end or ends of the dimension lines and emphasize the extent of the dimensioned length. AutoCAD’s default arrowhead style is the closed, filled type shown in Figure 14-2, but you can choose other symbols, such as dots or tick marks, to indicate the ends of the dimension lines. (Don’t get “ticked off about it,” but AutoCAD calls the line ending an arrowhead even when, as in the case of a tick mark, it doesn’t look like an arrow.)

Arrowheads: Appear at the end or ends of the dimension lines and emphasize the extent of the dimensioned length. AutoCAD’s default arrowhead style is the closed, filled type shown in Figure 14-2, but you can choose other symbols, such as dots or tick marks, to indicate the ends of the dimension lines. (Don’t get “ticked off about it,” but AutoCAD calls the line ending an arrowhead even when, as in the case of a tick mark, it doesn’t look like an arrow.)

![]() Extension lines: Extend outward from the definition points (also known as defpoints) that you select (usually by snapping to points on an object) to the dimension lines. By drafting convention, a small gap usually exists between the defpoints and the beginning of the extension lines. Also by convention, the extension lines usually extend just past the dimension lines; refer to Figure 14-2 for examples. AutoCAD makes dimensions look tidier by assigning fixed gap sizes and projection lengths for the extension lines, and if you need to dimension to circles or center lines, you can assign dash-dot linetypes to either or both extension lines.

Extension lines: Extend outward from the definition points (also known as defpoints) that you select (usually by snapping to points on an object) to the dimension lines. By drafting convention, a small gap usually exists between the defpoints and the beginning of the extension lines. Also by convention, the extension lines usually extend just past the dimension lines; refer to Figure 14-2 for examples. AutoCAD makes dimensions look tidier by assigning fixed gap sizes and projection lengths for the extension lines, and if you need to dimension to circles or center lines, you can assign dash-dot linetypes to either or both extension lines.

![]() Definition points (or defpoints): When you create any kind of dimension, placed on a special layer named (what else?) Defpoints, which the program creates when a dimension command is issued for the first time. These points are usually invisible because the objects being dimensioned are on top of them, but you can see where they sit by selecting a dimension to turn on its grips. The grips on the objects being dimensioned are on the dimension’s definition points. Because you wouldn’t want these points to appear when you plot drawings, the Defpoints layer does not plot; nothing created on the Defpoints layer ever plots.

Definition points (or defpoints): When you create any kind of dimension, placed on a special layer named (what else?) Defpoints, which the program creates when a dimension command is issued for the first time. These points are usually invisible because the objects being dimensioned are on top of them, but you can see where they sit by selecting a dimension to turn on its grips. The grips on the objects being dimensioned are on the dimension’s definition points. Because you wouldn’t want these points to appear when you plot drawings, the Defpoints layer does not plot; nothing created on the Defpoints layer ever plots.

By default, no matter which type of dimension you create, AutoCAD groups all parts of each dimension (the extension lines, dimension lines, arrowheads, and text) into a special associative dimension object. Associative has two meanings:

![]() The different parts of the dimension function as a single object. When you click any part of the dimension, AutoCAD selects all its parts.

The different parts of the dimension function as a single object. When you click any part of the dimension, AutoCAD selects all its parts.

![]() The dimension is connected to the points on the object that you specified when you drew the dimension. If you change the size of the object (for example, stretch a line), the dimension updates appropriately, as shown in Figure 14-3. The lines and arrows move, and the text changes to reflect the line’s new size.

The dimension is connected to the points on the object that you specified when you drew the dimension. If you change the size of the object (for example, stretch a line), the dimension updates appropriately, as shown in Figure 14-3. The lines and arrows move, and the text changes to reflect the line’s new size.

Figure 14-3: Changing objects automatically updates dimensions.

The good news is that you should have to adjust things to suit your specific industry or company only once, and then all dimensions will suit the specified standard. The really good news is that it usually takes only a bit of fine-tuning of the default settings to cover most of your dimensioning needs.

Dimension styles are saved within the current drawing. The really, really good news is that you can save this drawing as a template file (we cover templates in Chapter 4) so that all new drawings created from this template will have the dimension styles predefined. Or if you’re working in an office, someone may already have set up suitable dimension styles.

Creating dimension styles

A dimension style (or dimstyle, for short) is a collection of drawing settings, called dimension variables (or dimvars, for short), which are a special class of the system variables that we describe in Chapter 23.

![]() If you do need to create your own dimension styles or you want to tweak existing ones, use the DIMSTYle command. You can invoke it by clicking the small, diagonal arrow in the lower-right corner of the Dimensions panel of the Annotate tab on the Ribbon. The Dimension Style Manager dialog box opens, as shown in Figure 14-4.

If you do need to create your own dimension styles or you want to tweak existing ones, use the DIMSTYle command. You can invoke it by clicking the small, diagonal arrow in the lower-right corner of the Dimensions panel of the Annotate tab on the Ribbon. The Dimension Style Manager dialog box opens, as shown in Figure 14-4.

Figure 14-4: Yet another manager, this one for dimension styles.

Every drawing comes with a default dimension style named Standard (for imperial [feet-and-inches] drawings) or ISO-25 (for metric drawings) and a matching annotative style. (We cover annotative dimensions later in this chapter.) Although you can use and modify the Standard or ISO-25 style, we suggest that you leave them as is and create your own dimension style(s) for the settings that are appropriate to your work. This approach ensures that you can use the default style as a reference. More important, it avoids a potential naming conflict that can change the way your dimensions look if the current drawing is inserted into another drawing. (Chapter 18 describes this potential conflict.)

The system variable MEASUREMENT overrides the default for a specific drawing, but it affects only text, hatching, and noncontinuous line types.

Follow these steps to create your own dimension style(s):

![]() 1. On the Ribbon’s Home tab, click the label of the Annotation panel to open the panel slideout, and then click the Dimension Style button.

1. On the Ribbon’s Home tab, click the label of the Annotation panel to open the panel slideout, and then click the Dimension Style button.

Alternatively, if that just sounds like too much work, you can type D and press Enter. The Dimension Style Manager dialog box appears.

2. In the Styles list, select the existing dimension style whose settings you want to use as the starting point for the settings of the new style.

For example, select the default dimension style named Standard or ISO-25.

3. Click the New button to create a new dimension style that’s a copy of the existing style.

The Create New Dimension Style dialog box appears.

4. Enter a New Style Name and then select or deselect the Annotative check box. Click Continue.

Select the Annotative check box to create an annotative dimension style, or deselect it for a non-annotative style.

The New Dimension Style dialog box appears. (This dialog box is virtually identical to the Modify Dimension Style dialog box, which is displayed when you edit a dimension style.)

5. Modify dimension settings on any of the seven tabs in the New Dimension Style dialog box.

See the descriptions of these settings in the next section of this chapter.

6. Click OK to close the New Dimension Style dialog box.

The Dimension Style Manager dialog box reappears.

7. Click Close.

The Dimension Style Manager dialog box closes, and the new dimension style becomes the current dimension style that AutoCAD uses for future dimensions in this drawing.

8. Draw dimensions to test the new dimension style.

Adjusting style settings

After you click New or Modify in the Dimension Style Manager dialog box, AutoCAD displays a tabbed New Dimension Style dialog box or Modify Dimension Style dialog box (the two dialog boxes are identical except for their title bars) with a mind-boggling — and potentially drawing-boggling, if you’re not careful — array of settings.

Fortunately, the dimension preview that appears on all tabs — as well as on the main Dimension Style Manager dialog box — immediately shows the results of most setting changes. With the dimension preview and some trial-and-error setting changes, you can usually home in on an acceptable group of settings. For more information, use the Help feature in the dialog box: Just hover the mouse pointer over the setting that you want to know more about.

The following few sections introduce you to the more important tabs in the New/Modify Dimension Style dialog boxes and highlight useful settings. Note that whenever you specify a distance or length setting, you should enter a plotted size. We discuss plotting size scale factors in Chapters 13 (text) and 15 (hatching) and later in this chapter.

Following lines and arrows

The settings on the Lines tab and the Symbols and Arrows tab control the basic look and feel of all parts of your dimensions, except text.

Symbolically speaking

The settings on the Symbols and Arrows tab control the shape and appearance of arrowheads and other symbols.

A useful setting is Center Marks. Depending on which radio button you select, placing a radius or diameter dimension also identifies the center by placing a small center mark, or center lines that extend just beyond the circle or arc, or none. The default is the tick mark, but we prefer the line because normal drafting practice is usually to show center lines.

Tabbing to text

Use the Text tab to control how dimension text looks, which includes the text style and height to use (see Chapter 13) and where to place the text with respect to the dimension and extension lines. In particular, note the Text Style drop-down list, which shows the text styles available in the drawing. Click the three-dot button at the right end of the list to open the Text Style dialog box, and edit or create a suitable text style if one doesn’t already exist in your current drawing. The default Text Height in imperial units (0.180) is too large for most situations; set it to 1/8", 3mm, or another height that makes sense.

Getting fit

The Fit tab includes a bunch of options that control when and where AutoCAD shoves the dimension text if it doesn’t quite fit between the extension lines. The default settings leave AutoCAD in “maximum attempt at being helpful” mode. That is, AutoCAD moves the text, dimension lines, and arrows around automatically so that nothing overlaps. On rare occasions, AutoCAD’s guesses might be less than perfect. It’s usually easier to adjust the text placement by grip-editing the placed dimension, as we describe in the section “Editing dimension geometry,” later in this chapter, instead of messing with dimension style settings.

Most important, the Fit tab includes the Annotative check box. Using annotative dimensions, as we recommend in this chapter, makes dimensioning go a lot more smoothly!

Using primary units

The Primary Units tab gives you highly detailed control over how AutoCAD formats the characters in the dimension text string. You usually set the unit format and precision and maybe specify a suffix for unitless numbers, if it's not clear from the drawing which units you're using. You may also change the Zero Suppression settings, depending on whether you want dimension text to read 0.5000, .5000, or 0.5. ("Zero Suppression!" also makes a great rallying cry for organizing your fellow AutoCAD drafters.)

Other style settings

If your work requires that you show dimensions in two different systems of measure (such as inches and millimeters), use the Alternate Units tab to turn on and control alternate units. Alternate Units display both dimensions at a time.

If your work requires listing construction or manufacturing tolerances (for example, 3.5 +/-0.01), use the Tolerances tab to configure the tolerance format.

AutoCAD also includes a separate TOLerance command that draws special symbols called geometric tolerances. If you need these symbols, you probably know it (and you have our sympathies); if you’ve never heard of them, just ignore them. Search for the term Geometric Tolerance dialog box in the AutoCAD help system for more information.

AutoCAD also includes a separate TOLerance command that draws special symbols called geometric tolerances. If you need these symbols, you probably know it (and you have our sympathies); if you’ve never heard of them, just ignore them. Search for the term Geometric Tolerance dialog box in the AutoCAD help system for more information.

Changing styles

To switch to a different style, simply click in the dimension style window in the Dimensions panel of the Annotate tab on the Ribbon, and select a style from the drop-down list.

Scaling Dimensions for Output

You need to adjust the size of text and dimensions that are applied in model space to suit the final plotting scale of the drawing. By far, the best way to do this is to use annotative dimensions. Follow these steps to use the Annotative dimension style and apply an annotative scale to a dimension:

1. Start a new, blank imperial drawing.

Use the acad.dwt template.

2. Draw a horizontal line about 20 units long.

3. Apply a linear dimension (DimLInear, or DLI) to the line.

Pretty hard to read, isn’t it?

4. Switch to the Annotative dimension style.

Find the Dimension Style drop-down list that reads Standard in the upper-right corner of the Dimension panel of the Annotate tab on the Ribbon. Click it and then choose Annotative.

5. Change the current drawing annotation scale.

Select the 1:5 scale from the drop-down list, under the Annotation Scale button in the lower-right corner of the application window.

6. Use the DIMLIN command again and place a second dimension for the line.

Ah, that’s better, and it didn’t require any esoteric calculations. You now have to dimension that measure the length of the line, but the text and arrowheads appear at different sizes now.

To avoid confusing results, which is what has turned off most users from using annotative annotations, make sure that the Automatically Add Scales button in the lower-right corner is turned off. When Automatically Add Scales is enabled, AutoCAD updates all annotation objects that support annotative behavior when you change the current annotative scale. Having all scales attached to every annotation object is not ideal as it is much harder to control where the new scale representations appear in your drawing especially when they might not all be needed. We discuss this topic more in Chapter 13.

To avoid confusing results, which is what has turned off most users from using annotative annotations, make sure that the Automatically Add Scales button in the lower-right corner is turned off. When Automatically Add Scales is enabled, AutoCAD updates all annotation objects that support annotative behavior when you change the current annotative scale. Having all scales attached to every annotation object is not ideal as it is much harder to control where the new scale representations appear in your drawing especially when they might not all be needed. We discuss this topic more in Chapter 13.

Dimensioning details at different scales is always the most difficult type of dimensioning, unless you use annotative dimensions.

Here’s the easy way to create a multiscale drawing, such as the one in Figure 14-5:

1. Draw the object at full size in model space, including the small notch detail.

2. Select the 1:10 scale from the drop-down list under the Annotation Scale button in the lower-right corner of the AutoCAD window.

Figure 14-5: A drawing with a detail at another scale.

3. Apply the three dimensions that show in the Scale 1:10 view in Figure 14-5, using an annotative dimension style.

The figure shows paper space, but you’re working in model space.

4. Apply an annotative hatch and then draw the center line.

Turn to Chapter 15 if you’re not sure how to apply an annotative hatch.

5. Edit the properties of the hatch pattern and the 1.400 dimension to add 1:2 scale factors.

Chapter 15 discusses editing hatch patterns.

6. Make sure that the Automatically Add Annotative Scales button is turned off, and change the Annotation Scale to 1:2.

Three existing dimensions disappear, and the hatch and the 1.400 dimension resize themselves.

7. Add the 1.500 and 2.400 dimensions.

8. Switch to the paper space Layout1 tab. Click the viewport boundary and then grip-edit it approximately to the size and location shown.

Your model space drawing is probably not properly located, and the hatch and dimensions don’t show.

9. Click the viewport boundary again, click the Viewport Scale button (it probably reads similarly to 0.694694), and select 1:10 from the scale list.

The viewport zooms accordingly, and the hatch and 1:10 dimensions appear. If necessary, double-click in the viewport to enter model space, and then pan accordingly.

Don’t zoom or else you lose the scale setting!

Don’t zoom or else you lose the scale setting!

10. Double-click outside the viewport to return to the paper space layout.

![]() 11. Create a second viewport by using the VPORTS command, or simply copy it and then modify the existing one.

11. Create a second viewport by using the VPORTS command, or simply copy it and then modify the existing one.

12. Repeat Steps 8 and 9 on the new viewport, but use a Viewport Scale of 1:5.

Use the Lock/Unlock button to lock the viewports to prevent inadvertently messing with them.

Use the Lock/Unlock button to lock the viewports to prevent inadvertently messing with them.

There you have it — a multiview, multiscale detail drawing without duplicating any geometry or annotations. To see the real magic of it, go to the model space tab and observe that there’s still only one model of the part and no detail at the other scale. Use the Stretch command to play with the depth and location of the notch. Go back to the Layout1 tab to see how everything has automatically updated in both views. Magic!

Editing Dimensions

After you draw dimensions, you can edit the position of the various parts of each dimension and change the contents of the dimension text. AutoCAD groups all parts of a dimension into a single object.

Editing dimension geometry

The easiest way to change the location of dimension parts is to use grip editing, which we describe in Chapter 11. Just click a dimension, click one of its grips, and maneuver away. You’ll discover that certain grips control certain directions of movement. Selecting a dimension displays grips generally at the text, the ends of the dimension lines, and the defpoints.

In AutoCAD 2012, dimensions joined the group of objects that feature multifunction grips. Click the text grip on a linear dimension and use the grip menu to adjust the text location. Click an arrow grip, and you can create a continuous or baseline dimension from that end of the dimension, or you can flip the arrow. You can do these things by selecting a dimension and changing items in the Properties palette, but the multifunction grips are more efficient.

If you want to change the look of a component of a specific, individual dimension (for example, substitute a different arrowhead or suppress an extension line), use the Properties palette. (See Chapter 11 for more on the Properties palette.) All dimension settings in the New/Modify Dimension Style dialog boxes (see “Adjusting style settings,” earlier in this chapter) are available from the Properties palette when you select one or more dimensions.

Follow these tips for editing dimensions:

![]() Use smart breaks. In manual drafting, it’s considered bad form to cross object lines (that is, real geometry) with dimension lines or extension lines, or to have anything cross a dimension line. Dimension Break (DIMBREAK) prompts you to select a dimension and then an object to break it. The wild aspect is that it’s a smart break. If you do anything to the dimension or to the object being broken to change where they cross, the break follows accordingly — and if you change either item so that they no longer cross, the break heals itself. Better yet, if you change things again so that they cross again, the break reappears!

Use smart breaks. In manual drafting, it’s considered bad form to cross object lines (that is, real geometry) with dimension lines or extension lines, or to have anything cross a dimension line. Dimension Break (DIMBREAK) prompts you to select a dimension and then an object to break it. The wild aspect is that it’s a smart break. If you do anything to the dimension or to the object being broken to change where they cross, the break follows accordingly — and if you change either item so that they no longer cross, the break heals itself. Better yet, if you change things again so that they cross again, the break reappears!

![]() Use the DIMSPACE command. The Dimension Space (DIMSPACE) command applies a specified separation between existing linear or angular dimensions. Spacing dimensions equally — if you don’t use the DimBAseline command as they’re created — requires tedious manipulation with Snap Mode and the Move command.

Use the DIMSPACE command. The Dimension Space (DIMSPACE) command applies a specified separation between existing linear or angular dimensions. Spacing dimensions equally — if you don’t use the DimBAseline command as they’re created — requires tedious manipulation with Snap Mode and the Move command.

![]() You don’t always have to draw everything at full size. A fundamental mantra in AutoCAD is that you should always draw everything at full size. On occasion, however, it isn’t always practical. For example, you may design a power-transmission shaft for a large machine. The shaft is 4 inches in diameter and 12 feet long. It has a variety of splines, keyways, and bearing shoulders on each end, but the 11-foot section in the middle is simply a straight cylinder. If you draw it at full size and scale the plot to fit a suitable paper size, you’ll never see the details at each end.

You don’t always have to draw everything at full size. A fundamental mantra in AutoCAD is that you should always draw everything at full size. On occasion, however, it isn’t always practical. For example, you may design a power-transmission shaft for a large machine. The shaft is 4 inches in diameter and 12 feet long. It has a variety of splines, keyways, and bearing shoulders on each end, but the 11-foot section in the middle is simply a straight cylinder. If you draw it at full size and scale the plot to fit a suitable paper size, you’ll never see the details at each end.

![]() Common practice would be to draw the interesting end details, break out and remove the boring center section, and then bring the ends closer together. Now you can create a reasonable plot. The problem is that any dimension that crosses over the break, such as the overall length, doesn’t show the correct value. The solution is to override the value (we explain how a little later in the section “Editing dimension text”) and then to use the DIMJOGLINE command to insert a jog in the dimension line to indicate that the dimension line isn’t the true length.

Common practice would be to draw the interesting end details, break out and remove the boring center section, and then bring the ends closer together. Now you can create a reasonable plot. The problem is that any dimension that crosses over the break, such as the overall length, doesn’t show the correct value. The solution is to override the value (we explain how a little later in the section “Editing dimension text”) and then to use the DIMJOGLINE command to insert a jog in the dimension line to indicate that the dimension line isn’t the true length.

In spite of the name similarities, don’t confuse DIMJOGLINE with the DimJOgged command, covered earlier in this chapter. DIMJOGLINE is for linear dimensions, and DimJOgged is for radial dimensions.

In spite of the name similarities, don’t confuse DIMJOGLINE with the DimJOgged command, covered earlier in this chapter. DIMJOGLINE is for linear dimensions, and DimJOgged is for radial dimensions.

![]() Right-click for useful options. If you select one or more dimensions and right-click, the menu displays a number of useful options for overriding dimension settings or assigning a different style.

Right-click for useful options. If you select one or more dimensions and right-click, the menu displays a number of useful options for overriding dimension settings or assigning a different style.

![]() Sometimes, it’s better to create a new style. When you change a setting in the Properties palette, you’re overriding the default style setting for that dimension. If you need to make the same change to a bunch of dimensions, it’s usually better to create a new dimension style and assign that style to them. You can use the Properties palette or the right-click menu to change the dimension style that’s assigned to one or more dimensions.

Sometimes, it’s better to create a new style. When you change a setting in the Properties palette, you’re overriding the default style setting for that dimension. If you need to make the same change to a bunch of dimensions, it’s usually better to create a new dimension style and assign that style to them. You can use the Properties palette or the right-click menu to change the dimension style that’s assigned to one or more dimensions.

If you manually change a dimvar setting, the setting is applied to the current dimension style as an override, and all subsequent dimensions that are placed by using this style have the overridden appearance. This can cause much the same problem as overriding object properties instead of using different layers; if you edit a dimension style, all existing dimensions that use it update, including the ones that you hadn’t expected because they seem to be different from the ones you want.

If you manually change a dimvar setting, the setting is applied to the current dimension style as an override, and all subsequent dimensions that are placed by using this style have the overridden appearance. This can cause much the same problem as overriding object properties instead of using different layers; if you edit a dimension style, all existing dimensions that use it update, including the ones that you hadn’t expected because they seem to be different from the ones you want.

![]() Use a mask for the dimension text. You can use the Properties palette to turn on AutoCAD’s background mask feature (described in Chapter 13) for the text of individual dimensions: Select the dimensions, display the Text area in the Properties palette, and find the Fill Color item. Click in the list box, scroll down, and select Background to use the drawing background color (which usually gives the best results). To ensure that dimension text lies on top of other objects, use the TEXTTOFRONT (Chapter 13) or DRAWORDER (Chapter 18) commands.

Use a mask for the dimension text. You can use the Properties palette to turn on AutoCAD’s background mask feature (described in Chapter 13) for the text of individual dimensions: Select the dimensions, display the Text area in the Properties palette, and find the Fill Color item. Click in the list box, scroll down, and select Background to use the drawing background color (which usually gives the best results). To ensure that dimension text lies on top of other objects, use the TEXTTOFRONT (Chapter 13) or DRAWORDER (Chapter 18) commands.

![]() Don’t explode dimensions. The AutoCAD eXplode command on the Home tab’s Modify panel blows a dimension to smithereens — or at least into a bunch of line and multiline text objects. Resist the temptation. Exploding a dimension makes it much harder to edit cleanly and eliminates AutoCAD’s ability to update the dimension text measurement automatically.

Don’t explode dimensions. The AutoCAD eXplode command on the Home tab’s Modify panel blows a dimension to smithereens — or at least into a bunch of line and multiline text objects. Resist the temptation. Exploding a dimension makes it much harder to edit cleanly and eliminates AutoCAD’s ability to update the dimension text measurement automatically.

Editing dimension text

In most cases, you shouldn’t have to edit dimension text. Assuming that you draw the geometry accurately and pick the dimension points precisely, AutoCAD displays the right measurement. If you change the size of the associated object, AutoCAD updates the dimension and its measurement. However, you may occasionally want to override the dimension text (that is, replace it with a different measurement) or add a prefix or a suffix to the true measurement.

AutoCAD creates dimension text as multiline text, so dimension text has the same editing options as ordinary text. You have several ways to launch the dimension text editor, but the easiest is to simply double-click the dimension text.

AutoCAD displays the true dimension length as text in the actual dimension (and updates the text if you change the size or location of the object). You can override the true length by typing a specific length or another text string. You can preserve the true length but add a prefix or suffix by inserting <> (that is, the left and right angle-bracket characters) as placeholders for the dimension value. For example, if you enter About <> and the actual distance is 12.000, AutoCAD displays About 12.000 for the dimension text. If you stretch the object later on so that the actual distance changes to 14.528, AutoCAD changes the dimension text automatically to read About 14.528. Now you can appreciate the importance of drawing and editing geometry precisely!

Controlling and editing dimension associativity

When you add dimensions by selecting objects or by using Object Snap modes to pick points on the objects, AutoCAD normally creates associative dimensions, which are connected to the objects and move with them. This is the case in new drawings that were originally created in any release of AutoCAD starting with 2002.

![]() DIMREASSOCiate: If you have dimensions that aren’t currently associative (probably because they were created in older versions of AutoCAD) or they’re associated with the wrong objects, you can use the DIMREASSOCiate command to associate them with points on the objects of your choice. DIMREASSOCiate can be found on the Annotate tab’s Dimensions panel slideout, or you can type DRE and press Enter.

DIMREASSOCiate: If you have dimensions that aren’t currently associative (probably because they were created in older versions of AutoCAD) or they’re associated with the wrong objects, you can use the DIMREASSOCiate command to associate them with points on the objects of your choice. DIMREASSOCiate can be found on the Annotate tab’s Dimensions panel slideout, or you can type DRE and press Enter.

![]() DimDisAssociate: You can use the DimDisAssociate (DDA) command to sever the connection between a dimension and its associated object.

DimDisAssociate: You can use the DimDisAssociate (DDA) command to sever the connection between a dimension and its associated object.

![]() DIMREGEN: In a few special circumstances, AutoCAD doesn’t automatically update geometry-driven associative dimensions. (Maybe Autodesk should call them usually-fully-awake-but-occasionally-asleep-at-the-wheel associative dimensions.) In those cases, the DIMREGEN (no command alias) command fixes things.

DIMREGEN: In a few special circumstances, AutoCAD doesn’t automatically update geometry-driven associative dimensions. (Maybe Autodesk should call them usually-fully-awake-but-occasionally-asleep-at-the-wheel associative dimensions.) In those cases, the DIMREGEN (no command alias) command fixes things.

The associative dimensions we’re talking about here first appeared in AutoCAD 2002. Before that, AutoCAD had a more primitive kind of dimensioning. Dimensions were single objects, and they updated if you stretched an object

The associative dimensions we’re talking about here first appeared in AutoCAD 2002. Before that, AutoCAD had a more primitive kind of dimensioning. Dimensions were single objects, and they updated if you stretched an object