Refining the Research Process

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After completing this chapter, you should understand:

- How to execute the five basic steps in the research process.

- The process of identifying the issues or problems to research.

- How to collect evidence from data, authorities, and other sources.

- The skill of evaluating the research results and various alternatives.

- Develop and communicate a well-reasoned, documented memo and conclusion.

- How to remain current with the expanding body of authorities and data.

- International complexities in practice.

- Skills for the CPA exam.

METHOD OF CONDUCTING RESEARCH

Accountants are confronted with problems related to the proper accounting treatment for given transactions or the proper financial presentation of accounting data and disclosures. The focus of the research will determine what appropriate alternative principles exist and what potential administrative support exists for those alternatives. Apply professional judgment in selecting one accounting principle from the list of alternatives. Always use a systematic method for conducting research.

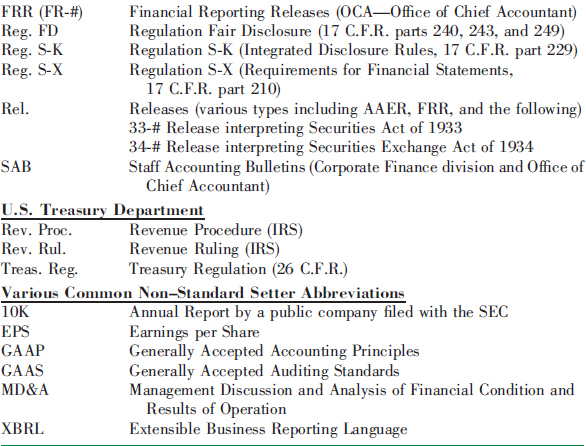

The following example problem demonstrates the application of the research methodology, as depicted in Figure 9-1. Think through each part of the problem and the research steps in order to comprehend the complete research process.

QUICK FACTS

Research identifies the relevant facts and issues, collects the applicable authorities, analyzes the results and identifies alternatives, develops conclusions, and communicates the results.

EXAMPLE FACTS: Sony is a multinational company headquartered in Tokyo, Japan, with over one thousand subsidiaries worldwide. Sony decided to expand its entertainment business in the United States, overseen by its subsidiary Sony-USA. Therefore, Sony-USA purchased two companies to form Sony Music and Sony Pictures. Because of these acquisitions, Sony assumed debt of $1.2 billion and allocated $3.8 billion to goodwill. On Sony's annual report filed with the SEC, Sony reported only two industry segments: electronics and entertainment. While Sony Music was profitable, however, Sony Pictures had produced continued losses of approximately $1 billion. Sony's founder, Akio Morita has asked your firm, XYZ, CPAs, to identify and explain any major potential accounting or tax concerns from these facts, but does not want you to worry about consolidations.

FIGURE 9-1 OVERVIEW OF THE RESEARCH PROCESS

Step One: Identify the Issues or Problems

To start the research, reread the problem provided to establish the facts and identify the issues or problems in clear and concise statements. Handle this task systematically by using the following three-part approach:

- Identify the preliminary problem.

- Analyze the problem.

- Refine the problem statements.

Identify the Preliminary Problem First, recognize potential problems in accounting, auditing, and tax. Company management, such as the controller or tax director, often initiates this problem identification process. Companies sometimes hire outside assistance from CPA firms. Because the initial statements of potential problems are usually very general and vague, one must develop the skill in analyzing the problem and then refining the statement of the problem or issues.

EXAMPLE of preliminary issue 1: Can Sony amortize the goodwill, or must the company write down the goodwill?

EXAMPLE of preliminary issue 2: Did Sony's financial statement presentation of two industries comply with relevant authorities?

Analyze the Problem Additional facts are often needed in research. Thus, the problem sometimes requires one to go back and acquire more from one's manager or even the client. Certain types of facts, such as related party situations and dates, are almost always relevant. Sometimes, an important fact to clarify is exactly which entity or person is the client.

Analyzing the problem is similar to an auditor conducting planning for an audit. The auditor will acquire more information about the business and potential risks. One might begin by going to a financial research database, such as S&P NetAdvantage, to acquire additional information about the company. Also, one might begin some problems by examining the relevant corporate Web sites. Usually, corporate Web sites offer an About the Company link, which explains more about the history and current structure of a company.

EXAMPLE of analysis: Corporate Web sites might help to reveal corporate structures for Sony, such as its subsidiary, Sony-USA, which has its own subsidiaries, such as Sony Entertainment, Sony Music, and Sony Pictures.

Examine historic SEC filings, such as the 10-K annual report for a public company or the Form 20-F, annual report for a foreign-owned public company. Prior to 2009, foreign companies had to reconcile their accounting from international accounting standards to U.S. GAAP. Included in annual report with the SEC are various non-financial items, such as the company's management, the board of directors, and qualitative and quantitative disclosures about the market risk. Key financial information in the SEC filing includes the company's financial data, operating and financial revenue prospects, major shareholders, and related party transactions. The Investor Relations part of the corporate Web site often provides easy access to annual reports filed with the SEC.

EXAMPLE of additional analysis: Prior to 2009, Sony has filed SEC Form 20-F for several years, which reconciled the accounting to U.S. GAAP. These filings are publically available through either the SEC database (EDGAR) or accessing the company's financial information in various financial research databases or LexisNexis Academic. Assume the review of Sony's SEC filings finds the following information:

- When Sony purchased the motion pictures business, it projected a loss for only five years. Sony assumed that Sony Pictures would become profitable.

- Sony suffered a significant loss after amortization and financing costs from the acquisition for the past four years. Moreover, in the current year, Sony Pictures sustained a loss of nearly $450 million, double the amount that Sony had planned. Sony Pictures had accumulated total net losses of nearly $ 1 billion.

- Goodwill of $2.7 billion associated with the acquisition of Sony Pictures was written down by Sony early in the year.

- Sony combined the results of Sony Music and Sony Pictures and reported them as Sony Entertainment. Sony Entertainment showed little profit. Sony's consolidated financial statements did not disclose the losses from Sony Pictures.

Refine the Problem Statement Refine the problem statement with more sophistication by incorporating the critical facts and the main authority for resolving the problem, after having identified the preliminary problem and engaged in initial problem analysis. Basic knowledge of relevant professional authorities helps the professional accountant to determine what additional facts are needed in refining the problem. Thus, a professional often conducts some initial research, as discussed in step two, and then returns to step one to refine the problem statement. The initial research may prompt the need for requesting additional facts.

QUICK FACTS

Summary of Step One: Identify the Issues or Problems

1. Identify the preliminary problem.

2. Analyze the problem.

3. Refine the problem statement.

EXAMPLE for more facts: The treatment for goodwill changed in 2001 for accounting purposes, the year for Sony's acquisitions is critical. Assume the desired analysis is for the current year. (One could actually determine the real year by examining corporate histories of Sony, such as presented in the chapter on databases and other tools.)

EXAMPLE of refined issue 1: Determine whether an annual write-down of goodwill and its impairment is necessary for an acquisition of a company with continued losses.

EXAMPLE of refined issue 2: Determine whether financial statement disclosures of two segments are needed when one industry has two businesses with different financial trends. The concern is to avoid misleading financial statement users in violation of Securities Exchange Act § 13(a).

Step Two: Collect the Evidence

The collection of evidence generally involves searching for all relevant authorities, whether in accounting, auditing, or tax. Often, one should also review insightful nonauthoritative sources, such as a survey of present industry practices, information about the industry, or relevant articles about the client company or problem.

Identify Keywords for Research Keywords are needed in some cases to locate the relevant authorities. The statement of the problem should enable one to generate the initial keywords necessary to access the appropriate sections of the authorities and professional literature. Additional keywords are sometimes identified after the search has begun, as one acquires more knowledge about various terms of art.

EXAMPLE: Identify keywords for research after the initial analysis and refined statement of the problem. Keywords are often used in a database search.

FIGURE 9-2 POTENTIAL KEYWORDS FOR THE SONY PROBLEM

EXAMPLE: Potential keywords for the Sony problem are shown in Figure 9-2.

To find relevant legal and professional authorities, the researcher may encounter cross-references that circle back to original starting point. Some identified keywords may prove useless in the search. Don't get discouraged. Continue to conduct the search for authorities and helpful nonauthoritative literature carefully and systematically. This approach will help make the process less frustrating and more efficient.

If applying U.S. accounting standards, then search the FASB Accounting Standards Codification. Figure 9-3 demonstrates the keyword citation diagram under old U.S. GAAP authorities.

A diagram sometimes aids the researcher in conducting and documenting an efficient literature search. Start by listing the keywords identified from the statement of the problem. Review these terms for relevant cross-references to other terms, whether broader, narrower, or related terms. Examine these additional terms for potential citations. List the citations in logical order, such as by the hierarchy of relevant authorities when one exists, such as for legal authorities, government accounting, or auditing authorities. Always start with the highest level of primary authority. Use authoritative support to explain or further interpret part of the stronger authority.

Locate and Examine the Relevant Authorities Determine the appropriate financial accounting framework and database to use to check for current standards. Use FASB Accounting Standards Codification to find relevant, authoritative citations to solve research issues involving U.S. GAAP. Use IFRS/IAS to resolve international GAAP that a foreign multinational company is likely to use even for SEC filings. If using IFRS/IAS, determine whether to use the less complicated IFRS for small to medium sized entities. If one does not have subscription access to the sources, remember that an accounting database may help locate relevant accounting information. Ideally, reference the primary authorities as precisely as possible, such as where in the FASB Accounting Standards Codification or the IAS/IFRS the authorities arises. However, some firms are satisfied with a reference to the general standard at issue.

FIGURE 9-3 ACCOUNTING KEYWORD/CITATION DIAGRAM FOR THE EXAMPLE USING OLD U.S. GAAP

RESEARCH TIPS

If a hierarchy of authorities exist, begin by examining its highest level.

A hierarchical structure of authorities often exists for the relevant accounting, auditing, or tax authorities. Recall that some official accounting standard-setting bodies continue to maintain a hierarchy of authorities, such as the IASB, GASB, or FASAB. If a hierarchy does exist, begin the review of authorities by examining the highest-level authorities. Note the scope of any authorities reviewed. Save time by scanning potential authorities for their relevance. Avoid making detailed reviews of authorities and pronouncements that are not applicable to the specific facts and issues for the transaction under investigation.

EXAMPLE on goodwill: A summary of the relevant authorities on goodwill is as follows:

Goodwill is an intangible asset that often arises from a business combination. It is a separate line item in the statement of financial position. Goodwill is not amortizable because it has an indefinite useful life. Potential impairment of goodwill in each reporting unit requires annual testing. ASC 350-20-35-1 and 28 (IAS 36.10). A reporting unit includes segments of an operating unit for which disclosure is needed. The impairment is generally measured by comparing the fair value to the reported carrying value of goodwill. ASC 350-20-35-4 (IAS 36.105). Impairment losses are recognized in the income statement. The notes to the financial statements must disclose each goodwill impairment loss if the loss is probable and can be reasonably estimated. The segment from which the business arose must disclose the loss. ASC 350-20-50-1 and 2 (IAS 36.129). Caution: Previously, goodwill was presumed to have a finite life and amortized over forty years. Also, the tax treatment of goodwill differs from financial accounting. Goodwill is a qualifying intangible for amortization over fifteen years under IRC § 197(a) and (d)(1)(A).

EXAMPLE on segment disclosure: The following is a summary of the relevant portions of accounting and SEC accounting literature on segment disclosure: Segment disclosure reporting is required for public companies in their annual financial statements. ASC 280-10-50-10 (IFRS 8.2). The objective of segment disclosure is to provide users of financial statements with information about the business' different types of business activities and various economic environments. ASC 280-10-50-6 (IFRS 8.1). Operating segments earn revenues and expenses, have results regularly reviewed by management, and have discrete financial information. ASC 280-10-50-1 (IFRS 8.5). Operating segments should exist if the revenue is 10 percent or more of the combined revenues, or assets are 10 percent or more of the combined assets. ASC 280-10-50-12 (IFRS 8.13).

Disclosure of segment information must include nonfinancial general information, such as how the entity identified its operating segments and the types of products and services from which each reportable segment derives its revenues. ASC 280-10-50-40 (IFRS 8.22). Required financial information includes the reported segment profit or loss, segment assets, the basis of measurement. ASC 280-10-50-29 (IFRS 8.21). Reconciliation is required of the totals of segment revenues, reported segment profit or loss, segment assets, and other significant items to corresponding business enterprise amounts. ASC 280-10-50-30 and 31 (IFRS 8.28).

Filing reports periodically with the SEC is required for every issuer of a security under the Exchange Act of 1934. The reports must include any information to ensure the required financial statements were not misleading in light of the circumstances. Prior to 2009, foreign-owned companies with registered securities had to reconcile the accounting in the annual financial statement to U.S. GAAP under SEC Form 20-F.

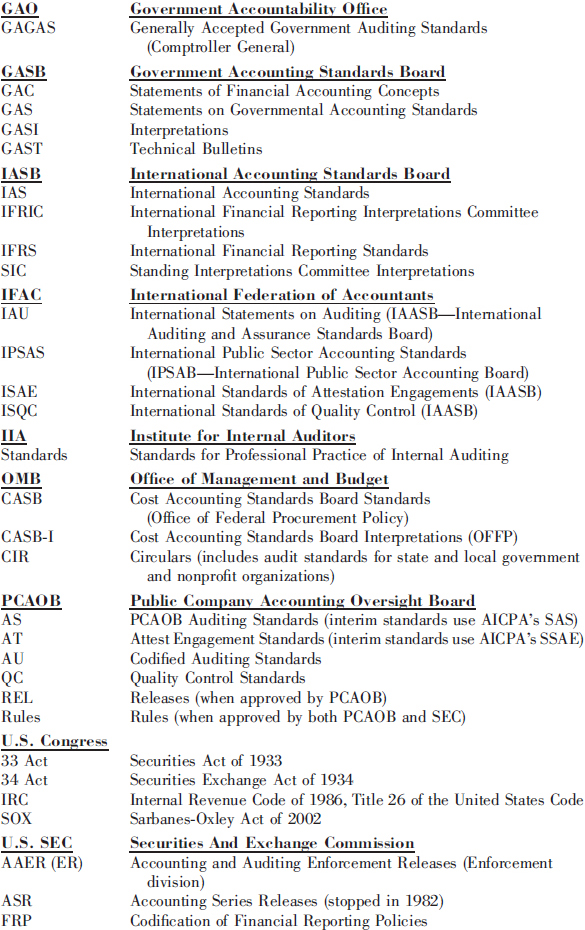

Sometimes obtain additional non-authoritative insight into the background and rationale underlying these key authorities. For example, one could examine old U.S. GAAP by looking at FASB Statements (FAS) No. 141 on goodwill and FAS 131 on segment disclosure. Abbreviations are regularly used for the research and its documentation, such as shown in Appendix A.

Do not ignore colorable authorities, pronouncements that other researchers might believe address the research problem, but you believe are irrelevant. Review colorable authorities for potential application and possible references to other appropriate sources. Discussions within these authorities may add insights into the problem at hand.

Review Insightful Nonauthoritative Sources Sometimes extend the search to insightful nonauthoritative literature or relevant standards within a profession. Nonauthoritative materials may help one understand the authorities. Nonauthoritative sources may include looking at guidance issued by AICPA; industry practices; published research studies; credible, relevant Web sites; databases for secondary source literature; and other respected sources. Reviewing nonauthoritative materials supplements the primary task to examine the real authorities for any accounting and auditing research.

QUICK FACTS

Nonauthoritative materials may help one understand the real authorities.

Determining how other companies with similar circumstances or transactions have handled the accounting and reporting procedures could involve a review of Accounting Trends and Techniques, issued by the AICPA. Sometimes, a discussion of the issue is appropriate. One normally does not discuss any specifics with professionals outside of one's accounting firm. If one does engage a discussion of the issue with outside peers, such as colleagues on the Internet, one must always exercise due professional care in completely protecting client confidentiality.

Use databases to find secondary sources. For example, investigate significant businesses competitors or hot issues within the relevant industry. Search within an article index database for insightful articles on a business or its operations. Access standards issued by a professional organization, such as the standards to help determine valuation for fair market value purposes.

QUICK FACTS

Summary of Step Two: Collect the Evidence

1. Identify keywords for research.

2. Locate and examine the relevant authorities.

3. Review insightful nonauthorities.

EXAMPLE of insightful nonauthoritative sources: Use financial research databases to better understand the music industry, Sony Music, or the issues. One might discover that Sony Music is the second-largest music company in the United States, which suggests that separate segmental reporting is needed. Relevant Web sites may provide one with valuable information, such as the studies provided by government agencies, financial organizations and markets (for example, the New Yok Stock Exchange, operated by NYSE Euronext), professional organizations (for example, the Institute of Internal Auditors), and search engines and their tools (for example, Google's advanced search page). Reviewing these Web sites sometimes helps the researcher find the latest information on the topic in question.

Step Three: Analyze the Results and Identify Alternatives

Exercise professional judgment in carefully reviewing the results and identifying potential alternative solutions. Evaluate the quality and amount of authoritative support for the research problem. Given a more principled approach to accounting standards, alternative solutions may have justification. Review the evidence and alternatives with other accountants knowledgeable in the field. One might check industry practices to verify any different possibilities for alternative reporting.

EXAMPLE problem: Recall the refined statement of the problem for Sony. The first issue was whether an annual write-down of goodwill was necessary for an acquisition of Sony Pictures after continued losses. The second issue was whether financial statement disclosures of Sony and Sony Entertainment were adequate under Securities Exchange Act Section 13(a) when Sony Entertainment had two businesses (music and pictures) with different financial trends.

EXAMPLE analysis: Through an examination of documents, discussions with persons involved, and application of accounting authorities, assume the following analysis is made:

- The carrying value of Sony Pictures exceeded its fair value. Similarly, the carrying amount of Sony Pictures' goodwill exceeded the implied fair value of Sony Pictures' goodwill. The impairment of goodwill loss was probable and can be reasonably estimated.

- Sony should report separately information about each operating segment that met any of the 10 percent quantitative thresholds.

- Sony may not combine Sony Music and Sony Picture as one reportable segment for many reasons—for example, they do not have similar economic characteristics. Other reasons include the fact thatthe businesses are not similar in either the nature of the products, the nature of the production processes, the type or class of customer for their products and services, or the methods used to distribute their products.

- Disclosure of Sony Music and Sony Pictures segmental information should fundamentally provide information about their reported segment profit or loss. Other information to disclose includes the types of products from which each reportable segment derives its revenues, any reconciliations needed from the total segment revenues, and interim period information.

- The amount assigned to goodwill acquired was significant in relation to the total cost of purchasing Sony Pictures. Therefore, Sony must disclose the following information for goodwill in the notes to Sony Entertainment's financial statements: (1) the total amount of goodwill and the expected amount deductible for tax purposes and (2) the amount of goodwill by reportable segment.

- The authoritative accounting standards provide principled support for recognizing writing down goodwill of an acquired entity with continuous losses. Write down goodwill when a loss is probable and can be reasonably estimated. Sony must provide separate financial reporting for Sony Pictures because Sony Music and Sony Pictures do not share similar economic characteristics.

RESEARCH TIPS

Support the conclusion with logical, well-reasoned analysis.

Step Four: Develop a Conclusion

A conclusion is generally a very short statement answering the issue. The conclusion should logically arise from well-reasoned analysis. The conclusion is often placed after the statement of the problem. If more than one issue exists, have the conclusion address each issue.

EXAMPLE of conclusion on Issue 1: The write-down of goodwill of an acquired entity with continuous losses is required.

EXAMPLE of conclusion on Issue 2: The financial statement disclosure of only two industries when one industry has two businesses with different financial trends is misleading.

EXAMPLE of combined conclusion: The authoritative literature supports the write-down of the goodwill of an acquired entity with continuous loss. The amount of the write-down is equal to the difference between the carrying value of goodwill and the fair value. The financial statement disclosure of only two industries when one industry has two businesses with different financial trends is misleading.

Step Five: Communicate the Results

Communicate the results of the research using the writing and oral skills discussed in a previous chapter. Communication of research results are often sent to clients in a brief, formal letter. Recall that e-mail is more generally reserved for more informal communications.

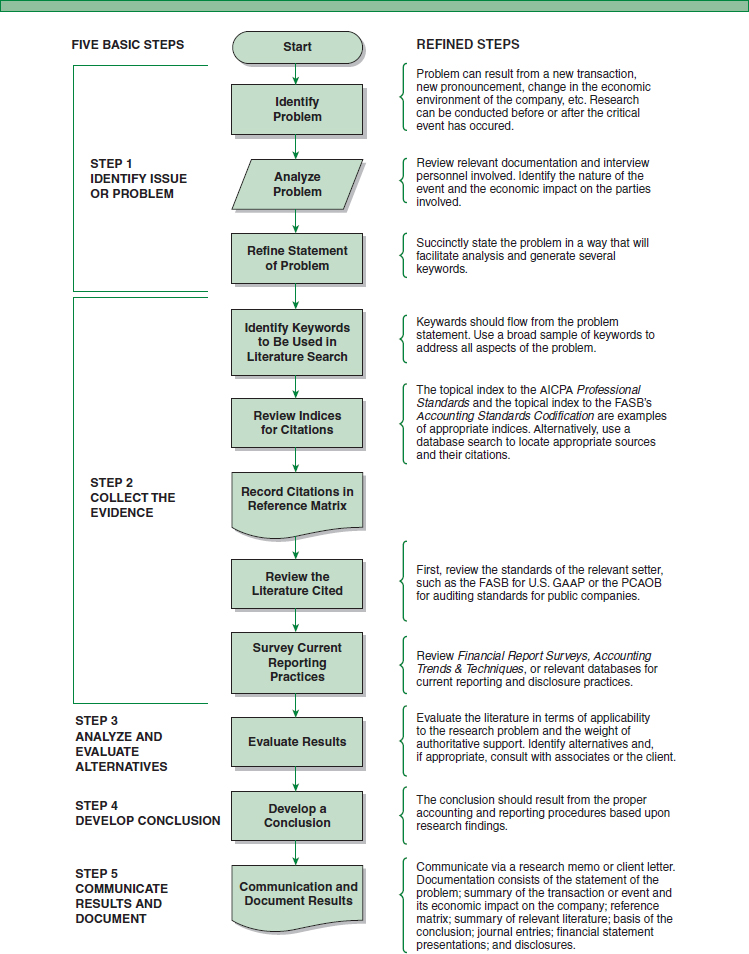

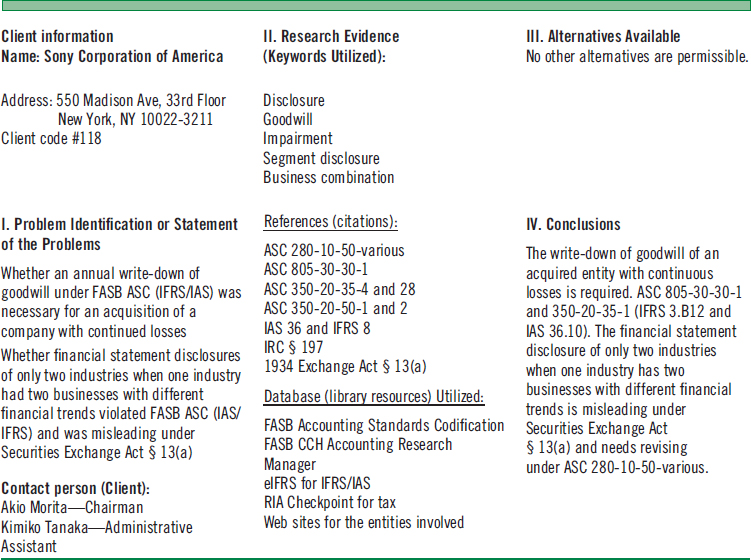

Document any research results. An example of a documentation worksheet that an accounting firm might use to organize the pertinent research information for its records using U.S. GAAP is shown in Figure 9-4. Given the time pressures within the profession, sometimes, the relevant portions of the authorities are simply copied and pasted into a document and attached to the document worksheet. While the authors advocate as much precision as possible, given current practices in accounting research, the example document worksheet provides the authors' view of the appropriate documentation needed for references to the accounting authorities.

RESEARCH TIPS

Document the relevant research and communicate appropriately.

A research memo includes detailed documentation. Such a memo is often appropriate for more sophisticated clients or problems. Slightly different structures for research memos and documentation exist among accounting firms. A brief research memo using both ASC and IAS/IFRS is shown in the appendix. In general, a research memo should include the following documentation:

QUICK FACTS

Summary of the Research Steps

1. Step One: Identify the Issues or Problems

2. Step Two: Collect the Evidence

3. Step Three: Analyze the Results and Identify the Alternatives

4. Step Four: Develop the Conclusions

5. Step Five: Communicate the Results

- A statement of the relevant facts and the issues or problems

- A summary of the conclusions

- References to legal and authoritative literature used, along with a brief explanation of the relevant parts of the authority

- The application of authorities, including a description of the authoritative support for each alternative; Explain why the alternatives were discarded and the recommended procedure or principle was selected.

The precision expected for documentation should increase in future years due to the increased documentation requirements under PCAOB audit standards, the easier research capabilities from FASB accounting standards codification, and increased legal penalties during the last decade. A well-documented memo is more likely to assure any reviewer that the researcher has an understanding of the authorities and the research problem.

LESSONS LEARNED FOR PROFESSIONAL PRACTICE

Many challenges confront researching effectively and efficiently. By using the suggested five-step process, one is more likely to solve the problem accurately and in a time-efficient manner. While research is both an art and a science, as one develops more experience in research, one will find the research easier and exciting. Make sure the research work is well documented. One never knows when one's work will get tested within the firm's quality review program, reviewed by an auditor (perhaps in a peer review process), inspected by the PCAOB if one is part of a registered firm, or even defended in court.

FIGURE 9-4 EXAMPLE DOCUMENTATION WORKSHEET OF RESEARCH UNDER U.S. GAAP

Professional accounting research of accounting authorities based on codified principles is much easier than the old system in the United States of various rules-based pronouncements in the GAAP hierarchy. Recall that the FASB's accounting standards now use the more conceptual approach, similar to the IAS/IFRS, which the SEC is considering as a replacement for GAAP in 2014. Then use professional judgment in the application of the standards, particularly in a litigious society.

SEC accounting research is important not only for its direct application to public companies, but also for those learning to comprehend the potential regulatory environment that all accountants could face if additional crises arise in the profession.

Absorb the examples in this chapter by locating and reading each authority cited. The process of finding and reading the authorities will give you a better feel for the real research process. The inspiration for this example arose from SEC Accounting and Auditing Enforcement Release No. 1061. While the case oversimplifies those facts, it lays a foundation from which to more easily tackle the entire case.

REMAIN CURRENT IN KNOWLEDGE AND SKILLS

Remain current in knowledge by studying new updates of authorities or new pronouncements. A systematic plan to remain current usually achieves the best results. Regularly read accounting and business periodicals, newsletters, and other sources. Currency is essential with the typical expansion of accounting, auditing, and tax authorities. Consider adopting some of the following techniques in your plan to remain current in knowledge:

- Use checklists: Maintain a checklist of new developments to assist in remaining current. Accountants prepare listings of updates to the FASB Accounting Standards Codification or new pronouncements and indicate which clients the change may affect. Pronouncements having no direct immediate impact on any client are often placed in a “rainy day” reading file.

- Summarize new authorities: Acquire or prepare summaries of new authorities at regularintervals. Such summaries identify and describe new legal, accounting, auditing, and tax authorities. Distribute the information to staff members through e-mail, presentations within the firm, attendance at continuing education seminars, or other means.

- Read periodicals: Read several accounting and business periodicals that summarize and explain new authorities. For example, read the Wall Street Journal, the AICPA's Journal of Accountancy, and leading professional publications in one's area of expertise, such as Internal Auditor or the Tax Adviser. Successful accountants regularly engage spend time reading about new professional standards, technological enhancements for practice, management concerns, and many other accounting and business topics.

- Check database updates: Check for news on a company of interest or specialized industry news of interest.

- Browse Web sites: Browse Web sites that capture relevant information on a timely basis, which is then reviewed by the practitioner. Use the newsgroups on the Internet to discuss topics of interest to you and your clients.

- Read accounting newsletters: Take advantage of sophisticated newsletters that update practitioners on current events. Newsletters are distributed by standard setters, publishers, large accounting firms, and others. They are increasingly being distributed via e-mail. Major newsletters by standard setters include the following:

- Action Alert. FASB summarizes board actions and future meetings in this weekly publication, available through e-mail.

- GASB Report. GASB summarizes new statements, exposure drafts, interpretations, or technical bulletins in a quarterly publication.

- CPA Letter. AICPA produces this online newsletter to address such topics as AICPA board business, new pronouncements on auditing, disciplinary actions against members, upcoming events, and more. This newsletter is one of almost twenty newsletters created by the AICPA. Other newsletters are often targeted toward specialty areas in accounting.

Remaining knowledgeable on every detail of all new authorities is not possible. However, every practitioner must develop and consistently use various techniques to acquire current professional knowledge. Currency is especially important with authorities and pronouncements that directly affect one's clients. Participate in continuing professional education to help learn about new developments in a formal, structured setting.

Remain current in skills, whether by continued research practice or training. Accountants will need even more skills in the future for new research opportunities, analysis, communication, or other needs. Today's professional world is much different from what the accountant experienced a generation ago, with the advances in technology, increased complexities in business, expanded sources of authority, increased regulation, and other developments.

RESEARCH TIPS

Remain current in knowledge and skills by continued reading, training, and practice.

The professional accounting world will undoubtedly continue to evolve as new business practices develop, changes in the economy occur, and financial scandals are uncovered. Failure to remain current in either knowledge or skills is likely to violate one's professional responsibilities and increase the chances of losing one's job, professional sanctions, costly malpractice lawsuits, or government action.

INTERNATIONAL COMPLEXITIES IN PRACTICE

In a global economy, one may desire to research the data, professional authorities, or legal environment in other jurisdictions. For example, researching authorities enables one to have a more sophisticated discussion with accounting professionals in a foreign country and best represent their multinational clients who conduct business in multiple countries. However, due diligence in understanding, researching, analyzing authorities and data, and communicating solutions is essential.

Increasingly, accountants are accessing foreign authorities or data to engage in collaborative work or ask foreign professionals sophisticated questions. Yet, differences around the world, both cultural and societal, may lead to various interpretations or actions based on the same data or professional authorities. Foreign regulators sometimes provide formal or informal interpretations or guidance on IFRS. One should not assume that all parts of the world have the same degree of professional commitment in reporting or high enforcement standards. Reporting incentives are influenced by such factors as a country's legal system, strength of the auditors, and a company's financial compensation scheme.

Outsourcing of accounting work to low-cost jurisdictions is likely to continue to increase, especially as more countries adopt IFRS/IAS. The accountants overseeing any outsourced work need to exercise extra due care to ensure that the foreign professionals meet the professional standards interpretations that are expected in the United States or other highly developed country.

SKILLS FOR THE CPA EXAM

Skills in practice identified for the CPA are classified in three categories: knowledge and understanding, application skills that include research and analysis, and communication skills. Knowledge is acquired through education or experience and familiarity with information. Understanding is the process of using concepts to address the facts or situation. Knowledge and understanding skills represent almost half of the skills tested on the CPA exam.

Application skills of judgment, research, analysis, and synthesis are required to transform knowledge. Judgment includes devising a plan of action for any problem, identifying potential problems, and applying professional skepticism. Research skills include recognizing keywords, searching through large volumes of electronic data, and organizing data from multiple sources. Analysis includes determining compliance with standards, noticing trends and variances, and performing appropriate calculations. Synthesis includes solving unstructured problems, examining alternative solutions, developing logical conclusions, and integrating information to make decisions. Application skills require technological competencies in using spreadsheets, databases, and computer software. Application skills represent between one-third and almost one-half of the skills tested on the CPA exam.

Communication skills include oral, written, graphical, and supervisory skills. Oral skills include attentively listening, presenting information, asking questions, and exchanging technical ideas within the firm. Written skills include organization, clarity, conciseness, proper English, and documentation skills. Graphical skills include organizing and processing symbols, graphs, and pictures. Supervisory skills include providing clear directions, mentoring staff, persuading others, negotiating solutions, and working well with others. Communication skills represent 10 to 20 percent of the skills tested on the CPA exam.

Using the five-step research process demonstrated in this chapter substantially helps to develop the necessary skills for the CPA exam. For any research problem, learn the facts and understand the problem or issues. Acquire knowledge about the client's needs and desires in order to understand the alternative and best solutions to the problem. Knowledge and understanding of accounting should also include the various standard setters and their authoritative sources and the nonauthoritative sources available in various databases, Web sites, hardbound books, newsletters, and other secondary sources.

Use application skills such as identifying keywords for research. Develop the skills of locating and reviewing the relevant authorities. Analyze how the authorities apply to the particular facts in the research problem. Synthesize information with the help of insightful, nonauthoritative sources. Use professional judgment as you refine the issues with greater specificity and develop well-reasoned conclusions.

QUICK FACTS

Skills include knowledge and understanding, application through research and professional judgment, and effective communication.

Develop strong communication skills not only for the CPA exam and research memos, but in handling the day-to-day tasks and interactions that typify the work of accountants and business professionals. Communicate the results of the research, as appropriate.

Although the CPA exam tests knowledge, application, and communication skills in much shorter questions than in the professional world, the goals presented are the same in preparing one as the knowledgeable and skilled professional for the various work that accountants perform.

SUMMARY

One should follow the five-step research process to (1) identify the issues or problems, (2) collect the evidence, (3) analyze the results and identify the alternatives, (4) develop the conclusions, and (5) communicate the results. The professional accountant must remain knowledgeable about current professional standards and develop skills in researching accounting, auditing, and tax issues. These attributes increase management's confidence and respect in your work as a accountant, auditor, or tax professional. By following the advice in this text, you are more easily able to fulfill your future professional role and responsibilities.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- What is the focus of accounting, auditing, and tax research?

- What is the three-part approach used to identify the problem or precise issue?

- Explain two ways to collect evidence.

- How are keywords used to evaluate and collect evidence?

- How might one determine accounting alternatives?

- What is the purpose of a research memorandum?

- What documentation is needed in the research process?

- How will you keep current on authoritative accounting standards?

- What are some of the complexities in international practice?

- What skills are needed for the CPA exam?

EXERCISES

1. Examine 17 CFR part 229.306 and explain the legal requirements for an audit committee. Hint: Use either a legal database, such as LexisNexis Academic, or search Title 17 of the Code of Federal Regulations.

2. Locate SEC Accounting and Auditing Enforcement Release No. 1062. What did that SEC release discuss? Hint: In the SEC Web site, while accountants refer to the source as AAER, the SEC will list the same release as FR-#. The release is issued by the Enforcement division of the SEC. It is often more productive to use a commercial service with a stronger index. LexisNexis and CCH's Accounting Research Manager are examples of two databases having many SEC releases.

3. Does a tax treaty exist between the United States and Japan? If so, when was it signed?

4. Compare the international treatment of segment reporting to the U.S. GAAP treatment.

5. Identify the competitor companies to Sony Music and how they rank. Identify your sources.

6. Major Research Problem 1: An audit partner of a CPA firm invested in a computer side business with a member of the board of directors of a public company that sells insurance and is an audit client of that CPA firm. Identify any potential problems. Conduct preliminary research to find the relevant source at issue. Refine the problem statement. Research and locate the relevant professional authorities and determine if there is any colorable authority in the law that prohibits such a relationship. If so, try to find the interpretation of the law that the SEC may have issued. Analyze, consider alternatives, and develop the conclusion. Write a research memo on the problem.

7. Major Research Problem 2: Midwest Realty, Inc., is a regional real estate firm. Andrea Midwest incorporated the firm eleven years ago. She is the founder, president, and the majority stockholder. Recently, Midwest decided to expand her successful local real estate firm into a regional operation. She established offices in major cities across the Midwest. Midwest Realty, Inc. leased the office space. The standard lease agreement included a ten-year, noncancelable term and a five-year option renewable at the discretion of the tenant. Two years ago, the residential home market was depressed in the Midwest due to movement of factory jobs abroad, a shaky economy, and tight credit policies. So Midwest decided to eliminate ten offices located in depressed economic areas that she believed would not recover in the housing market during the next five years. This year, Midwest Realty, Inc. closed the ten offices. Midwest Realty, Inc., however, was bound by the lease agreements on all these offices. The company subleased four of the ten offices, but continued to make lease payments on the six remaining vacated ones. Midwest Realty properly classified the lease commitments as operating leases. The controller for the company, Calvin Brain, expressed concern to Midwest about the proper accounting for the lease commitments on the six remaining offices available for subleasing. Brain believes they must recognize that the future lease commitments are a loss for the current period. However, the executives of Midwest disagree and believe that the rental payments are period costs to recognize as an expense in the year paid. Midwest is confident that the company can sublease the vacant offices within the next year and avoid booking a loss and corresponding liability in this accounting period. Midwest has, however, given Brain the job of researching this problem and making recommendations supported by current authoritative accounting pronouncements. Brain has asked your firm, XYZ, CPAs, to help in the development of the recommendations. Complete all five steps for this research problem, documenting each step.

APPENDIXA

Abbreviations Commonly Used in Citations

An alphabetized list of organizations creating professional or legal authorities shows the major accounting, auditing, or tax abbreviations for their sources. This list includes various FASB accounting authorities discontinued after the FASB Accounting Standards Codification and accounting authorities previously discontinued by the AICPA.

Issuance Abbreviation Title of Issuance (Division of the Standard Setter or Comment)

APPENDIX B

Sample Brief Memorandum

RE: Sony's Goodwill and Segment Reporting

Facts:

Sony is a Japanese multinational company that decided to expand its entertainment business in the United States. Sony purchased CBS Records and Columbia Pictures to form Sony Music and Sony Pictures. Because of these acquisitions, Sony assumed debt of $1.2 billion and allocated $3.8 billion to goodwill. On Sony's Annual Report filed with the SEC, Sony reported only two industry segments: electronics and entertainment. While Sony Music was profitable, Sony Pictures produced continued losses of approximately $1 billion. When Sony purchased the motion pictures operations, it projected a loss for only five years because it assumed that the motion pictures entertainment would become profitable. However, Sony suffered a significant loss after amortization and the costs of financing the acquisition for the past four years. Moreover, in the current year, Sony Pictures sustained a loss of nearly $450 million, double the amount that Sony had planned. To date, Sony Pictures has had total net losses of nearly $1 billion. Early in the year, Sony declared that it had written down $2.7 billion in goodwill associated with the acquisition of Sony Pictures. Sony combined the results of Sony Music and Sony Pictures and reported them as Sony Entertainment. Little profit was shown in Sony Entertainment. Sony's consolidated financial statements did not disclose the losses from Sony Pictures.

(1) Whether an annual write-down of goodwill and its impairment is necessary under FASB ASC for the acquisition of a company with continued losses.

(2) Whether financial statement disclosures of two segments are needed when one industry has two businesses with different financial trends in order to avoid misleading financial statement users under Securities Exchange Act Section 13(a).

Conclusions:

(1) A write-down of goodwill of an acquired entity with continuous losses is required.

(2) The financial statement disclosure of only two industries when one industry has two businesses with different financial trends is misleading and needs revising.

Authorities on goodwill:

A summary of the relevant authorities on goodwill is as follows:

Goodwill is an intangible asset that often arises from a business combination ASC 805-30-30-1 (IFRS 3.B12). It is a separate line item in the statement of financial position. Goodwill is not amortizable because it has an indefinite useful life. Potential impairment of goodwill in each reporting unit requires annual testing ASC 305-20-35-1 and 28 (IAS 36.10). A reporting unit includes segments of an operating unit for which disclosure is needed. The impairment is generally measured by comparing the fair value to the reported carrying value of goodwill. ASC 350-20-35-4 (IAS 36.105). Impairment losses are recognized in the income statement. The notes to the financial statements must disclose each goodwill impairment loss if the loss is probable and can be reasonably estimated. The segment from which the business arose must disclose the loss. ASC 350-20-50-1 and 2 (IAS 36.129).

Caution: Previously, goodwill was presumed to have a finite life and was amortized over forty years. Also, the tax treatment of goodwill differs from financial accounting. Goodwill is a qualifying intangible for amortization over fifteen years under IRC § 197 (a) and (d)(1)(A).

Authorities on segment disclosure:

The following is a summary of the relevant portions of accounting and SEC accounting literature on segment disclosure:

Segment disclosure reporting is required of public companies in their annual financial statements. ASC 280-10-50-10 (IFRS 8.2). The objective of segment disclosure is to provide users of financial statements with information about the business's different types of business activities and various economic environments. ASC 280-10-50-6 (IFRS 8.1). Operating segments earn revenues and expenses, have results regularly reviewed by management, and have discrete types of financial information. ASC 280-10-50-1 (IFRS 8.5). Operating segments should be recognized if the revenue is 10 percent or more of the combined revenues or assets are 10 percent or more of the combined assets. ASC 280-10-50-12 (IFRS 8.13). Disclosure of segment information must include nonfinancial general information such as how the entity identified its operating segments and the types of products and services from which each reportable segment derives its revenues. ASC 280-10-50-40 (IFRS 8.22). Required financial information includes the reported segment profit or loss, segment assets, the basis of measurement. ASC 280-10-50-29 (IFRS 8.21). Reconciliation is required of the totals of segment revenues, reported segment profit or loss, segment assets, and other significant items to corresponding business enterprise amounts. ASC 280-10-50-30 and 31 (IFRS 8.28).

Filing reports periodically with the SEC is required for every issuer of a security under the Exchange Act of 1934. The reports must include any information needed to ensure that the required financial statements were not misleading in light of the circumstances. Prior to 2008, foreign-owned companies with registered securities had to reconcile the accounting in the annual financial statement to U.S. GAAP under SEC Form 20-F.

Application of authorities:

- The carrying value of Sony Pictures exceeded its fair value; the carrying amount of Sony Pictures' goodwill exceeded the implied fair value of Sony Pictures' goodwill. The impairment of goodwill loss was probable and can be reasonably estimated.

- Sony should report separate information about each operating segment that met any of the 10 percent quantitative thresholds.

- Sony may not combine Sony Music and Sony Pictures as one reportable segment for any of the following reasons. They do not have similar economic characteristics. These businesses are not similar in the nature of the products, the nature of the production processes, the type or class of customer for their products and services, and the methods used to distribute their products.

- Sony should disclose segmental information for Sony Music and Sony Pictures, providing information about their reported segment profit or loss. Other information to report includes the types of products from which each reportable segment derives its revenues, any reconciliations needed of the total segment revenues, and interim period information.

- The amount assigned to goodwill acquired was significant in relation to the total cost of the acquiring Sony Pictures. Thus, Sony must disclose the following information for goodwill in the notes to Sony Entertainment's financial statements: (1) the total amount of goodwill and the expected amount deductible for tax purposes and (2) the amount of goodwill by reportable segment.

- The authoritative sources require recognizing writing down goodwill of an acquired entity with continuous losses. Write down goodwill when a loss is probable and can be reasonably estimated. On the other hand, Sony must provide separate financial reporting for Sony Pictures because Sony Music and Sony Pictures do not share similar economic characteristics.