Tax Research for Compliance and Tax Planning

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After completing this chapter, you should understand the following:

- Tax research goals.

- Tax research challenges.

- Tax research databases, such as RIA Checkpoint.

- Primary tax authorities, particularly the Code, treasury regulations, and cases.

- The tax research process.

- Professional standards affecting U.S. taxation.

Many taxpayers acquire professional assistance in completing their tax returns. Complexity in tax law and its application make strong tax research skills even more important. The purpose of this chapter is to present information and guidance in conducting tax research for both tax compliance and tax planning. The tax research methodology is actually very similar to accounting and auditing research.

TAX RESEARCH GOALS

The objective of tax research is to maximize the taxpayer's after-tax return or benefits. The objective is not necessarily to produce the lowest possible tax liability. Clients may value certainty of tax results or seek to minimize potential disputes with the IRS. This difference in viewpoint—maximizing after-tax benefits as opposed to minimizing tax—is especially important when one realizes that many tax-planning strategies involve some trade-off with pretax income, either in the form of incurring additional expenses, receiving less revenue, or both.

Tax researchers must distinguish between tax evasion, tax avoidance, and abusive tax avoidance. Tax evasion consists of illegal acts, such as making false statements of fact, to lower one's taxes. Tax advisors have professional responsibilities and must not condone any tax evasion. Tax avoidance seeks to minimize taxes legally, such as avoiding the creation of facts that would result in higher taxes. Tax avoidance is often the objective of tax research. The IRS now targets abusive tax avoidance by promoters of tax shelters and taxpayers investing in transactions that the IRS believes are intentionally being used to misapply the tax laws.

QUICK FACTS

Tax avoidance legally seeks to minimize taxes.

Tax research is an examination of all relevant tax laws given the facts of a client's situation in order to determine the appropriate tax consequences. The term tax research may vary depending on the context. Academic tax research is sometimes theoretical or policy-oriented research with the objective of providing new information that might describe the behavioral consequences of a change in the tax law or that will help shape decisions on how to change the tax law. Applied tax research addresses existing tax law, with the objective of determining its application to a given situation. In this book, the term tax research is used solely in the professional sense, to relate to the tax problems of specific taxpayers rather than to society at large.

TAX RESEARCH CHALLENGES

Begin tax research by determining the relevant facts. Many tax disputes involve questions of fact rather than questions of law. Two common factual disputes include determining fair market value of property and the amount of deductible business expenses incurred, especially while traveling away from home on business. Presentation of the facts may include the arguments made by both the taxpayer and the IRS as well as the decision by any prior court.

EXAMPLE: Does receipt of a diamond necklace constitute an excludable gift under Section 102 or taxable compensation for services?

Discussion: The result depends upon all facts and circumstances relevant to the case. True love suggests the necklace is an excludable gift under Section 102; a one-evening relationship might suggest the payment of the diamond necklace is gross income under Section 61 as a return for companionship services. Any dispute with the IRS in such a situation is a question of fact, not law.

The researcher must also identify the precise legal issues for a given set of facts. Too often, there is a tendency among novice tax researchers to rush into a search for legal authority without an adequate understanding of the problem. The following example can help illustrate the benefit of spending time in the initial steps to determine the relevant facts and legal issues.

EXAMPLE: The taxpayer operated refuse dumps. Land was acquired for business use. Land is not depreciable. What should the taxpayer argue to obtain a depreciation deduction?

Discussion: Argue that the purchase price was primarily for the holes in the land for refuse, not the land itself. As the holes were filled in, the taxpayer depreciated the assigned cost of the holes. By characterizing part of the purchase as acquiring refuse holes, the taxpayer in John J. Sexton1 was successful in taking a tax deduction. Less imaginative taxpayers and advisors had overlooked this idea.

After determining the facts and issues, the researcher must search for relevant legal authorities from among the massive array of tax authorities. Tax research is a process by which relevant tax law is applied to a given set of facts. To find the authority, it helps to have knowledge of how the tax law is organized and to develop skills in careful reading and analysis of the law. The law always controls, even if it contradicts accounting, economic, social, or moral theory.

QUICK FACTS

In tax research, more than one correct solution may exist.

The challenge is to select the correct legal authorities. In some situations, more than one answer may exist in law. The tax researcher may then inform the client on the relative merits and tax benefits of each defensibly correct option. Usually, however, only one tax result has an appropriate weight of legal authority. Determining the cutoff between a defensible tax treatment and one that is not defensible depends on whether the legal authorities backing the position provide substantial authority. Although applying this standard is learned more through experience and professional judgment, the evidence should support winning one's case in the majority of instances.

Three types of activities involve tax research: tax compliance, tax planning, and tax litigation. For tax compliance, tax returns are typically prepared. Tax accountants generally perform both tax compliance and tax planning work. Lawyers also engage in tax planning and handle tax litigation work to take a tax case to court.

Tax compliance is sometimes referred to as closed-fact engagements. All the facts have already occurred when the work is being performed. For tax compliance, the researcher's job is limited to discovery of relevant facts and law because the factual burden of proof generally rests with the taxpayer in the event of an audit.

Tax-planning engagements are sometimes referred to as open-fact engagements because not all of the relevant facts have transpired. Tax planning considers how to carefully execute tax avoidance, that is, controlling the facts that actually occur in order to produce an optimal after-tax result for the taxpayer. The rendering of well-researched tax planning advice is generally regarded as the hallmark of a true professional.

Tax litigation arises after the taxpayer is audited and intensifies if settlement with the IRS is not reached. The work may begin by double-checking prior tax research and researching the more rarely used tax sources that are beyond the practical scope of this text for accountants. If significant litigation potential becomes apparent, the tax accountant or client should consult with an experienced tax attorney.

TAX RESEARCH DATABASES

Tax research databases include both primary and secondary authorities. The two most used primary authorities by accountants are the Code and Regulations. Secondary sources are useful for acquiring a basic understanding of topics. A popular secondary source is the Masters of Tax Guide, which summarizes the tax law. Today's tax professionals generally use tax research databases through a publisher's Web site, or use a DVD to ensure access when the Internet is not available.

Several publishers produce databases that are useful for tax research. Some researchers use the massive online legal databases, such as LexisNexis and Westlaw, discussed in the prior chapter. Other researchers use specialized tax research databases, such as those provided by the Research Institute of America (RIA) and Commerce Clearing House (CCH).

QUICK FACTS

Tax services in a tax research database help find relevant cases.

Both RIA and CCH tax databases include primary tax authorities and helpful secondary sources, such as tax services, citators, news updates, and journal articles. RIA's tax database RIA Checkpoint includes RIA's tax services: Federal Tax Coordinator and United States Tax Reporter. CCH's tax database Intelli Connect includes CCH's tax services: Standard Federal Income Tax Reporter and Tax Research Consultant. An important difference between the RIA and CCH tax databases is how each displays the results. While RIA Checkpoint shows the number of results by source category, CCH's Tax Research Network mixes the results but displays them by what the CCH software believes is most relevant.

Popular Web sites for the tax researcher are presented in Figure 7-1. The Web has enabled Congress, the IRS, the courts, and others to make their sources more available. The IRS Web site provides downloadable tax forms and instructions as well as plain English, unofficial versions of the Treasury Regulations and daily news updates.

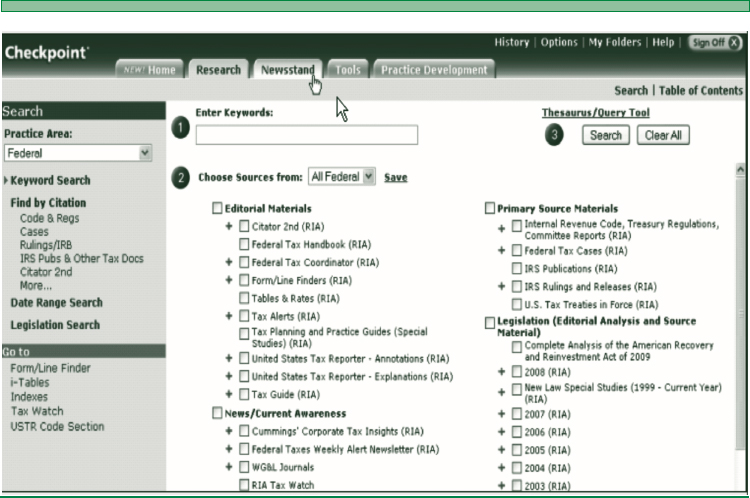

RIA Checkpoint

RIA Checkpoint contains various tax research libraries, such as international, federal, state, and local, and estate planning. The opening research screen should appear as in Figure 7-2. One tab on top of the opening screen is “Training and Tips.” Use this tab to access “Getting Started” and the “Demo,” which are listed on the left side of the screen. Various choices for practice areas in tax are provided in the drop-down box in the upper left side of the RIA Checkpoint screen. The researcher usually wants to limit the research to the relevant parts of the federal practice area of taxation.

FIGURE 7-2 RIA CHECKPOINT OPENING SCREEN

PRIMARY TAX AUTHORITIES

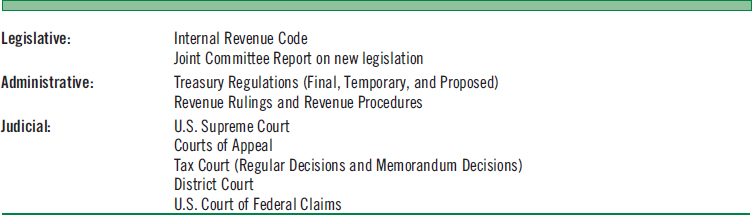

An understanding of the primary sources of tax authority and how to utilize RIA Checkpoint database and its tax services will help the researcher locate the relevant law. Primary authority generally comes from the following sources:

- Statutory sources: The Internal Revenue Code, the U.S. Constitution, and tax treaties

- Administrative sources: Treasury Regulations, Revenue Rulings, and revenue procedures

- Judicial sources: Case decisions from the various courts

This section overviews the most widely primary sources of tax law. Constitutional concerns are not discussed because they rarely arise for federal tax, although they may arise for state taxes.

Tax treaties usually attempt to eliminate double taxation from income subject to tax in two countries. If the tax transaction at issue involves a foreign national or arose in a foreign country, tax researchers should begin their research determining if there is any applicable tax treaty. The United States has tax treaties with many countries. Some tax treaty information is available on the IRS Web site, as well as in tax research databases. Using an index on the Web, such as www.taxsites.com (international page), can also help lead to finding relevant tax treaty information.

The Code

The Code or IRC is the popular name for U.S. statutory law on federal taxation. The official name is the Internal Revenue Code of 1986 as Amended, located in Title 26 of the United States Code. The Code is the statutory foundation of all federal tax authority. When new tax legislation is passed, such as the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, the provisions in the law are codified, that is, rearranged logically in the Code.

To cite a specific tax provision, tax researchers use the Code section number and the specific provisions within that Code section. For example, cite “Code § 11(a),” instead of the more cumbersome “Subtitle A, Chapter 1, Subchapter A, Part II, Section 11, Subsection (a) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986 as Amended.” If a Code section refers to one of the organizational divisions of the Code, the researcher should use the table of contents to clarify what code sections are included.

A Find by Citation approach in a tax research database is an easy and efficient method to view a specific Code section. For RIA Checkpoint, the link to the citation is on the left side of the screen. The citation approach often provides a template box to assist the researcher in accessing the desired Code section or other authority.

Always cite a provision within a Code section with as much precision as possible. Thus, it is essential to know that each section is divided into subsections, paragraphs, subparagraphs, and clauses. Within parentheses following the Code section number, subsections use lowercase letters, paragraphs use numbers, subparagraphs use capital letters, and clauses use lowercase roman numerals. Only if a Code section existed back under the 1939 codification does the current Code not include a small letter before a paragraph number, such as section 212(3) for the deduction of tax services.

RESEARCH TIPS

Always cite as precisely as possible within a Code section.

The general rule of a Code section is usually provided in subsection (a). Read subsection (a) carefully and scan the remaining subsection headings to search for other relevant provisions in the Code section. Reading the Code requires moving around within the section and even into other sections in order to understand the meaning of a phrase used with the Code section. A Code section will sometimes explicitly reference another Code provision. More often, however, make an effort to connect different sections that effect the meaning of a phrase within a Code section. The Code requires careful reading skills. Little words such as “or” between paragraphs can create big differences in meaning. Thus, the reader should consider highlighting significant words so as to place the reading into proper perspective.

FIGURE 7-3 ANALYSIS OF A CODE OF A SECTION

RESEARCH TIPS

To understand the general rule of a Code section, read subsection (a) carefully.

EXAMPLE: How does one read the example of Section 132 on fringe benefits related to employee discounts?

Discussion: First read subsection (a) carefully to understand the general rule that among the excludable fringe benefits is a qualified employee discount. Then scan the subsections to search for other relevant provisions. Subsection (c) defines qualified employee discount. Section 132(c)(1)(A) states that, for property, the discount cannot exceed “the gross profit percentage.” Look to see if this term is defined within subsection (c) or elsewhere in the Code section. Indeed, Section 132(c)(2) defines the gross profit percentage. Note that the paragraphs (1) and (2) are more indented than the subsections (a) and (c) and the subparagraph (A) is even further indented.

The Code may seem confusing at first. For example, the Code sometimes defines concepts differently for various sections.

EXAMPLE: Do related parties for tax purposes include brothers and sisters?

Discussion: Related parties for purposes of Code Section 267, disallowance of losses between related parties, are defined in subsection (b) to include brothers and sisters as part of the family relationship for purposes of constructive ownership of stock. In contrast, Section 318, on the constructive ownership of stock for purposes of defining related parties for subchapter C corporations, does not consider brothers and sisters as related.

Many tax researchers now rely extensively on online access to read the Code and other relevant tax law. Historically, accountants acquired a new paperbound edition of the Code after each major tax law change. They also bought a useful secondary source book, such as CCH's Master Tax Guide.

RESEARCH TIPS

Topical tax services are easier to read, but annotated ones provide more depth.

Tax services are secondary sources that are especially helpful in finding relevant cases. The online version of a tax service reproduces multivolume, comprehensive sets of books that are organized either topically or by Code section number. Topical tax services, such as RIA's Federal Tax Coordinator, are generally easier to read and provide footnote support to the primary authorities. Tax services organized by Code section number are commonly called annotated tax services and provide short annotations on cases and sometimes Revenue Rulings that interpret that Code section. Annotated tax services, such as CCH's Standard Federal Income Tax Reporter, usually provide a greater depth of research than a topical tax service. Both RIA and CCH provide both topical and annotated tax services.

For recently enacted changes to the Code, one should examine the Report by the Staff of the Joint Committee on Taxation (“the Blue Book”). The Joint Committee produced compromises to reconcile differences in proposed legislation passed by both the House of Representatives and the Senate. The Blue Book explains those changes and often provides the basis for future Treasury Regulations interpreting the modified Code sections. Tax services will often include the most relevant parts of the Blue Book. Less reliable congressional sources include the House Ways and Means Committee Reports, the Senate Finance Committee Reports, congressional hearings, and individual speeches inserted into the Congressional Record.

Administrative Authorities (Particularly Treasury Regulations)

Once Congress has enacted a tax law, the federal government's executive branch implements it by interpreting and enforcing the law. Thus, the Treasury Department creates Treasury Regulations. The IRS, the largest division of the Treasury Department, issues lesser administrative authorities and enforces the tax law through audits and making adjustments in a taxpayer's self-reported tax liability.

Treasury Regulations Treasury Regulations provide general guidance that interpret and clarify the statutory law. The number of Treasury Regulations interpreting a code section varies widely. While some Code sections have many treasury regulations, other sections have no regulations.

Three major types of Treasury Regulations are proposed, temporary, and final regulations. Treasury Regulations first appear in proposed form in the Federal Register. The IRS has sometimes subsequently modified or withdrawn a proposed regulation. After major changes in the Code, temporary regulations are eventually issued, which are legally binding, but expire after three years. Final regulations are issued only after going through the official process for notice and comment at public hearings. The regulation is then published as a Treasury Decision in the Federal Register and later codified into Title 26 of the Code of Federal Regulations.

QUICK FACTS

Treasury Regulations interpret and clarify the Code.

Two types of final Treasury Regulations are legislative and interpretive. Legislative regulations arise when a Code section directs the Secretary of the Treasury to create regulations to carry out the purposes of the section. Interpretive regulations arise under the authority of Code Section 7805(a), which expressly provides that the Treasury Department Secretary “shall prescribe all needful rules and regulations for the enforcement of this title.” You must comply with both types of final Treasury Regulations.

To find a relevant regulation, scan the titles of the regulations that interpret the code section at issue. While most tax research databases attempt to link the regulations to the related Code section, some databases make an effort to link each regulation to a particular Code subsection or paragraph. If the title of the regulation appears to have potential application, look over the contents of that regulation. Then carefully read potentially relevant parts of the regulation. Some Treasury Regulations are helpful by providing clarifying examples on a topic. Other Treasury Regulations may directly address topics that the relevant Code section did not mention.

EXAMPLE: Does the deduction for travel away from home on business include a business associate?

Discussion: Section 162(a)(2) allows a deduction for ordinary and necessary business expenses for traveling while away from home on business. Travel expenses are disallowed for the spouse, dependent, or other individual accompanying the taxpayer under Section 274(m)(3). The other individual does not include a business associate. Treas. Reg. § 1.274-2(g).

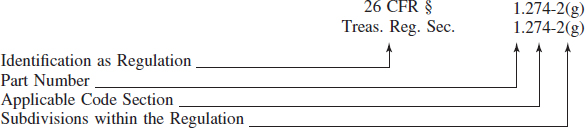

Notice that the citation for a Treasury Regulation references the Code section that the regulation interprets. The Code section that the regulation interprets is evident after the decimal point and before the hyphen that precedes the subdivisions of the regulation. Although Treasury Regulations are found in Title 26 of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), they are more commonly referenced merely by Treasury Regulation section. The citation for a Treasury Regulation begins with the part number that identifies the general area of taxation to which the regulation is related, such as “1” for an income tax regulation:

| Part 1 | Income Taxes |

| Part 20 | Estate Taxes |

| Part 25 | Gift Taxes |

| Part 31 | Employment Taxes |

| Parts 48, 49 | Excise Taxes |

| Part 301 | Procedural Rules |

RESEARCH TIPS

A Treasury Regulation citation identifies the Code section interpreted.

In the following example citation of a regulation, one can tell at a glance that the regulation cited applies to Code Section 274. However, the subdivisions of the regulation have no relationship with the subdivisions within the Code section. The “2” in the citation following the hyphen and “274” indicate that this is the second regulation issued interpreting Code Section 274. Two appropriate forms of a citation of the same regulation are as follows:

Carefully check that any Treasury Regulations relied upon remains applicable to the current Code section of interest. Parts of a regulation may become obsolete because of a recent change in the Code language. The Treasury Department is frequently slow to amend or remove regulations. Commercial tax services are often helpful in pointing out concerns with particular regulations.

Revenue Rulings and Revenue Procedures Revenue Rulings apply the law to a specific set of completed facts. Revenue Rulings are often based on further IRS review of previous private letter rulings issued upon taxpayers' requests concerning the tax outcomes of specific proposed transactions. In contrast to the general guidance provided in Treasury Regulations, Revenue Rulings provide issues, facts, and law and analysis on applying the law to a particular set of facts. They do not carry the same level of authority as Treasury Regulations do. Revenue Rulings are issued by the IRS and represent the position that IRS revenue agents must follow in auditing tax returns.

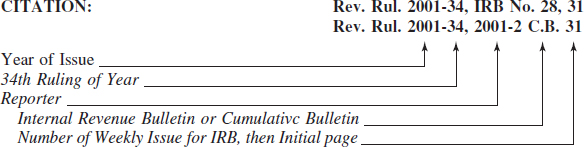

The citation to a Revenue Ruling does not reference the Code section that it addresses. However, for the researcher's convenience, a tax service, such as RIA Checkpoint, will sometimes follow the Revenue Ruling citation with the relevant Code section. The researcher should remove that Code section reference when citing the Revenue Ruling. Always check the status of a Revenue Ruling before relying on it. For example, the IRS may modify, revoke, or supersede a Revenue Ruling. For convenience, the major tax services provide update links or warnings to determine the current status of a Revenue Ruling. Revenue Rulings are first published in the Internal Revenue Bulletin (IRB) and later in the Cumulative Bulletin (CB). A researcher might encounter either of the following citations for the same Revenue Ruling:

QUICK FACTS

Revenue Rulings and Revenue Procedures represent the IRS position.

Revenue Procedures are created by the IRS to announce administrative procedures that taxpayers must follow. Revenue Procedures are similar in weight of authority to Revenue Rulings. They are both found in the same sources. They are also cited in the same manner except that the prefix “Rev. Proc.” is used instead of “Rev. Rul.”

Examples of lesser administrative authorities by the IRS that lack precedential value in court include IRS Notices and Private Letter Rulings (PLRs). IRS Notices are useful when they outline expected future Treasury Regulations that the IRS might take years to create. PLRs are issued on a proposed transaction but are binding on the IRS only with respect to the particular taxpayer requesting the ruling, assuming all material facts were disclosed.

IRS publications explain how to complete various tax forms and topics. For example, IRS Publication 901 discusses U.S. tax treaties. While the IRS publications are useful for tax compliance purposes, they merely interpret the law and are actually secondary authority. IRS publications are often used by taxpayers completing their own tax returns and by non-accountant tax preparers.

Caution: Many government sources are often miscategorized as primary sources because the government created the source. This miscategorization is evident in RIA Checkpoint's list of primary sources. Within this text, secondary authority exists when the source lacks precedential value for various taxpayers to rely on the source.

Judicial Sources of Tax Authority Judicial decisions in common law countries, such as the United States, are considered part of the law. Judicial law is created by consistently treating similar cases in the same fashion under the applicable statute and regulations. While Congress sets forth the words of law and the administrative branch interprets and enforces those words, it is the judiciary that has the final say as to what the words really mean when applied in a particular case.

QUICK FACTS

Judicial cases interpret the Code and the Treasury Regulations.

Examining prior judicial decisions to determine the meaning of a given phrase in the Code is sometimes necessary. To conduct the research on case law effectively, the tax researcher needs a working knowledge of judicial concepts, the various federal courts, and the hierarchy. Knowledge of the judicial system is necessary to appraise the authoritative weight of decisions rendered by the various federal courts.

U.S. Tax Court This specialized court considers only tax cases. Its nineteen judges are usually highly knowledgeable tax lawyers. Although the Tax Court is located in Washington, DC, judicial hearings are held in several major cities during the year. Most Tax Court cases involve only a single judge, who submits an opinion to the chief judge. The Tax Court's Web site reprints its recent decisions, provides its rules of practice, and gives other information.

QUICK FACTS

Taxpayers in Tax Court do not prepay the taxes in dispute.

Two types of Tax Court cases are processed: regular and memorandum. A regular decision is when the Tax Court's chief judge decides a case is announcing a new principle in the law. On rare occasions, en banc decision occurs, which involves a review by all of the Tax Court judges for an important tax issue. A memorandum decision is made if the Tax Court is just applying already announced principles to a different set of facts. Prior to 1943, both regular and memorandum decisions were published by the government under the title United States Board of Tax Appeals (BTA).

Many taxpayers use the Tax Court to litigate the IRS audit adjustment to avoid prepaying the amount of taxes in dispute. The Tax Court may rule differently on identical fact patterns for two taxpayers residing in different circuit court of appeals jurisdictions in case of inconsistent holdings by the circuit courts. This is because, within each circuit, the Tax Court will follow precedents of that court of appeals (known as the Golsen rule).2 Besides not having jury trials, the Tax Court has unique rules to expedite the court's process, such as requiring the taxpayer and IRS to work together to establish the facts.

The IRS will issue either an acquiescence or nonacquiescence for most Tax Court regular decisions that the IRS has lost. Acquiescence means the IRS expects to follow the decision of the Tax Court when dealing with cases of similar facts and circumstances. A nonacquiescence indicates the IRS will not follow the Tax Court's decision when handling similar cases. This IRS issuance does not apply to either memorandum decisions or decisions by any other courts. Announcements of either acquiescence (Acq.) or nonacquiescence (Nonacq.), are published in the IRB and CB.

RESEARCH TIPS

Tax Court's Small Claims division considers disputes of $50,000 or less.

The Small Claims division of the Tax Court considers tax disputes of $50,000 or less. The expedited process and less costly procedures are the advantages for a taxpayer to elect having the Small Claims division of the Tax Court decide the case. The disadvantage of using the Small Claims division is that appeals are not allowed. The Small Claims division decisions are not published by the government because they do not have precedential value. However, tax research databases will sometimes publish such nonprecedential authority.

Other Courts If a taxpayer prepays the amount in dispute with the IRS and then sues for a refund, the taxpayer must first use either a U.S. District Court or the U.S. Court of Federal Claims. Only in a district court can one obtain a jury trial. However, a jury can decide only questions of fact, not questions of law. Each state has at least one federal district court. About 25 percent of the U.S. Court of Federal Claims' cases are tax cases. This court was previously known as the U.S. Claims Court and the U.S. Court of Claims.

In the U.S. Court of Appeals, either taxpayers or the IRS may appeal decisions of the Tax Court and the district courts. The appeal is made to the circuit in which the taxpayer resides. Because there are thirteen courts of appeals (eleven regional ones, the DC Circuit, and the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit), the Federal Circuit appellate court will hear appeals on tax issues only if they arise from decisions of the U.S. Court of Federal Claims. Normally, a review by a court of appeals consists of a panel of three judges and is limited to the application of law, not the redetermination of facts. Courts of appeal are obligated to follow the decisions of the Supreme Court but not those from other circuit courts of appeal.

QUICK FACTS

Court of appeals decisions provide precedent within each circuit.

The U.S. Supreme Court is the ultimate forum for appeal. However, it considers only a handful of tax cases each year, usually those in which courts of appeal have reached different conclusions on the same issue. Either the taxpayer or the IRS can request the Supreme Court to review a court of appeals decision. The Supreme Court hears the case only if it grants the “writ of certiorari” (reported as “Cert. Granted”). If the Supreme Court refuses a case, certiorari is denied (reported as “Cert. Den.”). The Supreme Court simply will not review the case, and the decision of the court of appeals will stand.

QUICK FACTS

U.S. Supreme Court cases are precedent for all taxpayers.

Precedent is the principle that governs the use of prior decisions as law. The courts use precedents to build stability and order into the judicial system. Decisions concerning similar prior cases are used as guides when deciding new cases. The process of finding analogous cases from the past and convincing the tax authorities of the precedential value of those cases is the essence of judicial tax research.

The hierarchy of court decisions determines whether a case is precedent. A Supreme Court decision on an issue is precedent for all courts as long as the statute remains unchanged. A taxpayer sometimes tries to argue a narrow application of the court's holding or interpretation of the law so as to distinguish the unfavorable precedent. Court of appeals decisions provide precedent for all cases in their respective circuits. The decisions of other circuit courts of appeals are merely influential, not precedent. The Tax Court follows precedent set by the appellate court of the circuit in which the taxpayer resides. Thus, consistency in the application of law is maintained within a jurisdiction even though an inconsistency may exist in the law's application to taxpayers residing in other circuits.

FIGURE 7-4 SOURCES OF TAX AUTHORITY

STEPS IN CONDUCTING TAX RESEARCH

RESEARCH TIPS

The research process is based on facts, issues, authorities, and reasoning to support the conclusion.

Tax research consists of five basic steps, as explained in Chapter 1. Those steps, as applied in the tax research context are:

- Investigate the facts and identify the issues.

- Collect the appropriate authorities.

- Analyze the research.

- Develop the reasoning and conclusion.

- Communicate the results.

Step One: Investigate the Facts and Identify the Issues

Often, tax problems have a way of appearing deceptively simple to taxpayers. The taxpayer is often interested only in the final outcome and tax-planning advice. The tax adviser must always exercise due professional care in acquiring the facts and identifying the relevant legal issues regardless of the amount of money at stake.

EXAMPLE: Determine how much is deductable under Code Section 170 for making a charitable contribution of land costing $100,000 when it has a $250,000 fair market value.

Discussion: Depending on additional facts, the deduction can range from $0 to $250,000. Even the most cursory review of Section 170 reveals that the researcher needs to know more facts just to identify the real tax issues that impact the amount of any charitable deduction.

RESEARCH TIPS

The answer to many tax issues depends on the critical facts.

Preliminary research often causes the tax researcher to understand what additional facts are needed from the client. The new information might trigger new or more refined issues for research. The purpose of the following example is merely to illustrate the continually unfolding interrelationships between primary tax authorities and relevant facts in identifying and refining the real legal issues to research.

EXAMPLE: In researching the character of the contributed land as ordinary income or capital gain property, assume the tax advisor discovers that the taxpayer claimed all real estate holdings as investments, despite a history of many prior real estate transactions. What issues and conclusions should the tax adviser identify?

Discussion: The legal issue is whether the taxpayer's real estate activities constitute a trade or business under Section 162(a). If so, was the donated land held for sale in the normal course of the business? If the taxpayer was in the business of selling real estate, the land was held for sale in the normal course of that business, resulting in ordinary income, rather than capital gains which might benefit from lower tax rates.

Step Two: Collect the Appropriate Authorities

RESEARCH TIPS

Search techniques include keyword, table of contents, citation, and index approaches.

Search techniques needed to collect the appropriate tax authorities can include the keyword, table of contents drill-down, index, and citation approaches. The most difficult part of the search is to find relevant cases. While not every Code section and regulation has judicial cases interpreting their language, most sections have cases that apply the statutory and administrative law to a particular set of facts.

FIGURE 7-5 SEARCH BY TABLE OF CONTENTS APPROACH IN RIA ChECKPOINT

A keyword search is often used to find relevant cases interpreting the Code or regulations. However, note that the search engines for different databases do not always search the entire database. A keyword search is sometimes likely to overwhelm the researcher with many documents that are not on point. Also, tax research databases differ in presenting the search results.

A table of contents drill-down search approach in a tax database enables one to proceed from the relevant Code section to tax services to find relevant annotations of cases that interpret that Code section. Annotations provide a one- or two-sentence explanation of the case. For example, when one finds the relevant Code section and provision within it, most online tax services will provide hyperlinks to the authorities discussed. If the case appears potentially relevant, the researcher should then read the entire case to ensure its relevance, extract sufficient information to understand the case, and generally write a paragraph on that case.

FIGURE 7-6 SEARCH BY CITATION: RIA TEMPLATES FOR CODE AND REGULATIONS

The index approach is similar to viewing an index in the back of the book. Indices exist for the Code, tax services, and selected other sources. Access to the indices in RIA Checkpoint is near the bottom left side of the opening research screen.

Citations enable the researcher to collect the authorities quickly. Whether one uses online tax databases or hardbound books to find the case is irrelevant; the citation is the same. Case citations generally use the following format: case name,volume number, reporter, initial page number where the case begins, the court if not evident from the reporter, and year of the court's decision. When one uses a tax research database, note that the database's style of case citation may differ slightly from the official style that the tax researcher should use.

Tax publishers RIA and CCH provide useful court reporters that include all federal court decisions concerning taxation, except for those from the Tax Court. Thus, included in the reporters are tax cases from U.S. district courts, Court of Federal Claims, court of appeals, and the Supreme Court. The RIA court reporter is called American Federal Tax Reports (AFTR, AFTR2d, AFTR3d) while the CCH product is United States Tax Cases (USTC). AFTR and USTC are found in the publisher's tax research database: RIA Checkpoint or CCH Tax Research Network. Accountants usually cite non–Tax Court cases in either AFTR or USTC. Caution: USTC neither refers to Tax Court cases nor includes them.

Supreme Court decisions are published by the U.S. Government Printing Office in U.S. Supreme Court Reports (U.S.). They are also unofficially published by such reporters as AFTR and USTC. A parallel citation exists to show multiple locations for finding a case. A citation to a case need not include any nonofficial sources for accessing the case; however, it's often helpful to include such information. The following example provides a parallel citation to a tax decision by the Supreme Court: Ballard v. Commissioner, 544 U.S. 40; 95 AFTR2d 1302 (2005).

Courts of appeal decisions are officially published in the Federal Reporter (F., F.2d, F.3d), and the tax decisions are unofficially reprinted in RIA's AFTR series and CCH's USTC. The first name in a case citation indicates the party appealing the prior court's decision. The following citation refers to a 2008 decision by the court of appeals for the Federal Circuit: National Westminster Bank v. United States, 512 F.3d 1347; 2008-1 USTC 50,140 (Fed. Cir. 2008).

U.S. District Court decisions are officially published in the Federal Supplement (F. Supp., F. Supp. 2d). Finding the decisions of the U.S. Court of Federal Claims and its predecessor courts is more complicated. Decisions rendered between 1929 and 1932 and after 1959 appear in the Federal Reporter—2d or 3d Series (F.2d or F.3d), while those issued between 1932 and 1960 are in the Federal Supplement (F. Supp.). A sample citation is United States v. Textron Inc., 507 F. Supp. 2d 138, 2007 (D.R.I. 2007).

QUICK FACTS

A case citation generally includes the case name, volume number, court reporter, initial page number, court, and year.

Tax Court case citations distinguish regular and memorandum decisions because they are in different reporters. Tax Court regular decisions are published by the government in United States Tax Court Reports (TC). Tax Court memorandum decisions are published by RIA and CCH reporters called TC Memorandum Decisions (T.C. Memo) and Tax Court Memorandum Decisions (T.C.M.). The following illustrates the citation to different Tax Court decisions.

QUICK FACTS

Two types of Tax Court cases are regular and memorandum decisions.

Step Three: Analyze the Research

A working knowledge of primary tax authorities is needed because of the enormous volume and the many sources of tax authorities. Such knowledge should include both understanding the nature of the sources and where to locate them. By understanding the legal hierarchy of tax authorities, the researcher can assess their relative weight. For cases and Revenue Rulings, the strength of authorities varies depending on the court, the age of the decision as a proxy for a greater likelihood that the law has changed, and the client's set of facts.

The analysis of the tax research is often the most difficult part of tax research. General guidelines for analysis are listed below:

- The Code is the strongest authority. However, the Code does not always answer many questions arising from a given factual situation.

- Treasury Regulations are the next strongest authority.

- Court decisions interpret the Code and regulations. A court can overturn a Code section only if it is unconstitutional. A court will overturn a Treasury Regulation only if the regulation is totally unreasonable.

- Supreme Court cases apply to all taxpayers. Circuit court of appeals decisions apply only to taxpayers residing in that circuit. However, circuit court cases are often influential elsewhere.

- IRS Revenue Rulings and Revenue Procedures are binding only on IRS revenue agents, not on the courts. Thus, weight of authority for Revenue Rulings exists only if the taxpayer is arguing before the IRS.

RESEARCH TIPS

A citator is used to determine whether a case continues to have validity.

A citator is used to check whether a case continues to have validity. A citator presents the judicial history of a case. Courts may affirm or reverse a prior court's decision or any part of the case. The higher court may sometimes issue the appropriate legal standard and then remand the case back to the prior court for a decision that applies that law. A citator also traces subsequent judicial references to the case, which helps to indicate the influence of a court's reasoning on other courts. Figure 7-7 displays the citator in RIA Checkpoint.

EXAMPLE: A link to the citator in RIA Checkpoint appears on the search screen on the left side. In using the citator, the researcher enters the citation for the case to evaluate.

An ability to research effectively both primary and secondary tax authorities is a necessary skill for the tax advisor. Secondary authorities on taxation are often helpful in locating and assessing relevant primary tax authority. They may provide valuable analyses, research already performed by leading tax professionals and scholars, and unique insights on a wide variety of tax issues. Secondary authority does not carry precedential weight. Secondary sources that are more commonly used in tax are provided in Figure 7-8. Secondary authority generally comes from the following types of sources:

- Lesser IRS administrative pronouncements, such as private letter rulings (PLRs), IRS publications, and IRS notices.

- Tax service explanations, such as in RIA's Federal Tax Coordinator.

- Treatises and textbooks.

- Articles from professional tax journals and law reviews.

- Tax newsletters and Web sites.

RESEARCH TIPS

Secondary authority is often helpful for the initial research.

Step Four: Develop the Reasoning and Conclusion

In reaching a solution to a tax issue, the tax researcher will apply relevant tax authorities related to the issues and facts. As in accounting and auditing research, professional judgment in tax also plays an important role in reasoning. Always consider the weight of authority so as to start with the strongest, most logical source, such as a Code section or subsection. For cases, try to use the strongest cases possible, which depends on the level of the court, whether the judge's remark was the holding of the case or merely influential passing remarks (dicta), and the similarity of the facts. The reasoning includes a discussion of how each potentially relevant legal authority is applied to the set of facts or is distinguishable from them.

FIGURE 7-7 RIA CITATOR 2ND FOR UPDATING CASES

Document the relevant law and apply each source discussed in the reasoning before reaching a conclusion. In certain situations, no clear solution is apparent due to unresolved issues of law or perhaps incomplete facts from the client. Written documentation is important for communicating the research findings to others or constructing tax planning advice. Documentation of the research process is especially important if the client is audited on this tax issue. When the tax return is under audit, the person who completed the tax return two years ago may have departed. Carefully document the research to avoid both IRS penalties and litigation from an unhappy client.

RESEARCH TIPS

Document your tax research in a memo for the client file.

As part of tax planning, the tax professional will determine how to structure the facts and possible legal alternatives for the client's problem. The professional should present likely consequences for each alternative. The client, in discussion with the tax professional, will then select the best alternative given the facts.

FIGURE 7-8 POPULAR SECONDARY SOURCES IN TAX

Step Five: Communicate the Results

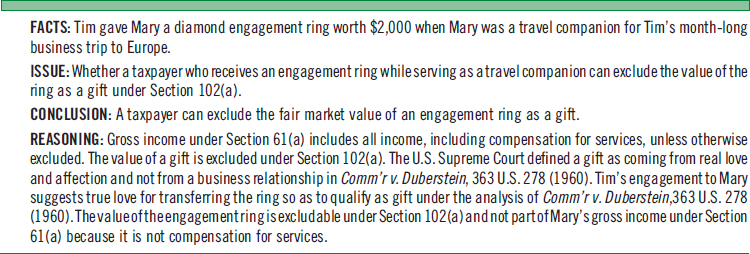

A structured tax research memo format for the completed tax research is usually used. Subheadings typically exist to assist the reader. The conclusion is often placed after the issues. An example of a very brief memo is provided in Figure 7-9.

In the reasoning, check that all relevant sources of authority are briefly discussed. A case is often presented in a separate paragraph with a sentence for the facts of the case, the court's holding, and the reasoning behind the court's decision. In the reasoning, it is best to explain how each authority discussed applies to the client's set of facts rather than assume that the reader will see the same connection of relevant law to the client's set of facts.

FIGURE 7-9 BRIEF RESEARCH MEMO ILLUSTRATED

A letter to the client about the research should focus on what the client wants to know, the bottom line results, and tax planning advice. The letter should clearly and briefly express the major points in a less technical format than a research memo. The client cannot often judge the quality of the research and may use the quality of the communications as a proxy to judge your abilities. The tax professional should follow up significant oral communications with a letter or e-mail.

QUICK FACTS

Develop strong writing skills for effective client communications.

Effective communication often requires a presentation tailored to the intended audience. Professional judgment is required in determining how much detail to express when preparing any given client letter, tax research memo, or other written document. The goal is to make sure that clients completely understand both the potential benefits and risks of any recommended actions. Whatever the level of technical sophistication of the client for whom the research is performed, a client letter should set forth at least a statement of the relevant facts, the tax issues involved, the researcher's conclusions, and the legal authorities and reasoning upon which the conclusions are based. Guidelines for preparing each section of the research report include the following.

Relevant Facts

- Include all the facts necessary for answering the tax question(s) at issue.

- Usually state the events in chronological order and provide a date for each event.

- Provide references to any available documentation of the facts.

- Let the client review the written description of the facts for accuracy and completeness.

Issues Identified

- State each issue as precisely as possible, referencing where in the Code the issue arises.

- Incorporate in each issue the critical facts for determining the applicable law.

- Describe each issue in a separate sentence.

- Arrange the tax issues in a logical order.

Conclusions

- State a brief separate conclusion for each tax issue presented.

- Review the quality of the written memo or client letter communications.

- Sign and date the client letter that communicates the results and tax planning advice.

Authorities and Reasoning

- Provide a detailed, logical analysis to support each of the research conclusions.

- Separately present the authorities and the reasoning underlying each issue.

- Always begin discussing a relevant Code section before going to a regulation or case.

- For court decisions, concisely summarize the facts, holding, and reasoning.

- Provide a proper citation for each authority mentioned.

- Apply the precise findings of each legal authority cited to the facts.

- Consider providing possible alternatives having a reasonable possibility of success on the merits of the issue. Assess the legal support underlying each alternative.

QUICK FACTS

A tax research memo provides facts, issues, conclusions, authorities, and reasoning.

PROFESSIONAL STANDARDS FOR TAX SERVICES

Various professional standards affect tax practice. Foremost is the IRS Circular 230, which governs who can practice before the IRS and provides enforceable rules of conduct and strict standards on written advice related to potential legally questionable tax shelters. Under Circular 230, a CPA, lawyer, and those passing an IRS exam to qualify as enrolled agents can practice before the IRS. Rules of conduct in Circular 230 include using due diligence and not working for a contingent or unconscionable fee in preparing any original tax return.

QUICK FACTS

IRS Circular 230 provides strict standards on written tax advice.

Circular 230 provides strict standards on any written tax advice, including e-mails regarding covered opinions on tax avoidance transactions, as identified in Treas. Reg. § 1.6011-4(b)(2). This standard has led most tax professionals to provide a disclaimer on every e-mail. Even more importantly, as a result of recent Circular 230 reforms, tax accountants have refocused on offering professional services rather than sales of questionable tax planning packages.

The AICPA Statements on Standards for Tax Services (SSTSs) supplement the AICPA Code of Professional Conduct for CPAs in tax practice. The SSTS address such topics as the use of estimates on the taxpayer's returns, making a departure from a position previously decided by the court or IRS administrative proceedings, and responsibilities after learning about an error on the taxpayer's previously filed tax return. The AICPA has also issued a few interpretations of these standards, such as one on tax planning. The SSTS are available on the AICPA Web site under its materials on taxation. Future tax professionals are encouraged to read these professional standards and apply them in practice.

EXAMPLE: When preparing or signing a tax return, when must a CPA in good faith not rely, without verification, on information that the taxpayer or third party prepares?

Discussion: If the information appears incorrect, incomplete, or inconsistent on its face or on the basis of other facts, the CPA has a duty to make further inquiry (SSTS No. 3).

QUICK FACTS

The CPA exam in the simulation often tests tax research skills using the Code and Treasury Regulations.

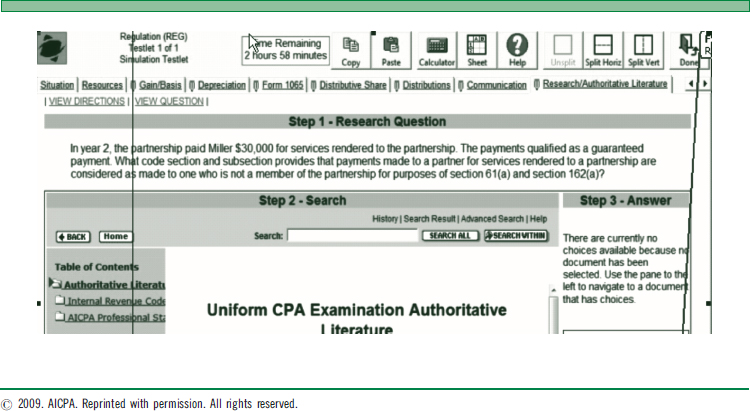

The CPA exam often tests tax research skills in the simulation part of the exam's regulation section. For the simulation, the CPA exam provides a database with a tab for research, providing the Code and the Treasury Regulations. The CPA exam now has several short simulation problems. The AICPA's simulation problem example shown in Chapter 1 is reproduced and answered in this chapter's appendix. One looks under the research tab to find the relevant Code or Treasury Regulations.

SUMMARY

Accountants perform tax research for both tax compliance and tax planning. For any tax issue, the researcher must find and understand the major primary authorities: the Code, Treasury Regulations, and cases. Using a tax research database such as RIA Checkpoint is a necessity in practice. Tax researchers must carefully cite to their authorities and apply them to the client's facts. Professional standards apply to accountants and tax professionals. In the process of understanding tax research, one develops an appreciation for the complexity, excitement, and skills required for a tax professional.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- Explain the difference between tax evasion, tax avoidance, and abusive tax avoidance.

- Identify tax research goals.

- Identify and explain the basic steps of the tax research process.

- Discuss the challenges in tax research.

- Distinguish between tax compliance and tax planning.

- Identify the differences between a Treasury Regulation and a Revenue Ruling.

- Explain the meaning of the term precedent for tax research.

- What does it mean when the IRS announces a nonacquiescence?

- Identify the sources that are published in the IRB.

- Besides Revenue Rulings and Revenue Procedures, identify three other types of sources that the IRS generates.

- Explain when one would encourage a client to go to district court rather than Tax Court.

- Discuss how to use RIA Checkpoint to find relevant cases.

- Identify what cases are provided in AFTR and USTC.

- Compare and contrast Tax Court regular decisions with Tax Court memorandum decisions.

- Diagram the court hierarchy, showing the three courts of original jurisdiction on the bottom, two courts in the middle, and the U.S. Supreme Court on top.

- Discuss the structure of a tax research memo.

- Locate three different tax Web sites, and identify three different items available on each Web site.

- Describe the analysis and reasoning in a tax research memo.

EXERCISES

1. Find each of the following on the Web:

- A copy of your state's 1040 tax form.

- A copy of Publication 597, “Information on the United States–Canada Income Tax Treaty.”

- Two proposed taxation bills, and briefly summarize each.

2. Which of the following tax sources are primary authorities?

- Tax services

- Tax Court memorandum decisions

- Revenue Procedures

- IRS publications

- Temporary Treasury Regulations

3. Use a tax research database to answer the following:

- Paraphrase Code Section 61(a)(4).

- What is the general content of Code Section 166(d)?

- Find the precise authority within the Code that defines net long-term capital gains.

- Find the precise authority within the Code that determines when the gain on the sale of a home is taxable.

4. Use a tax research database and answer the following questions. Then repeat the problem using a different tax research database and compare their ease of use.

- Conduct a search of the U.S. Treasury Regulations using the keyword “moving expenses.” List three documents from your search and their dates.

- Conduct a search of the IRB/CB using the keyword “tuition credit.” List the three most recent documents produced from your search. Use proper citation format.

5. After getting selected in Disney's training program, Minsu became a rock star. His family paid $22,000 to get Minsu trained. How much of these expenses paid by his family are deductible? Reference the specific authority in the Code and regulations.

6. Find the Code section that explains the amount of the penalty for failure to include reportable transaction information with the return. How much is that penalty?

7. Under Treas. Reg. § 1.6011-4, how is a reportable transaction described?

8. Central Michigan Medical Association (CMMA) is planning on hiring a new cardiologist who currently lives in Dallas, Texas. The cardiologist owns a home in Dallas. Due to the depressed housing market, he would incur a loss of $80,000 if it were sold. In order for the new doctor to relocate to Michigan, he requests that CMMA reimburse him for the loss to be incurred on the sale of his Dallas home. In conducting tax research, what are some tax issues to consider in regards to the tax treatment for the loss reimbursement? Identify the key issues as precisely as possible.

9. Use a tax research database and identify the general content of each of the following Internal Revenue Code sections:

- § 62(a)(2)

- § 162(e)(4)

- § 262(b)

- § 6702(a)

10. Use a tax research database and list the major Code sections for the following topics:

- Gift tax

- Capital gains

- Stock dividends

- Business energy credits

11. Identify the general contents of each of the following subchapters and parts of the Code:

- Subchapter A

- Subchapter C

- Subchapter K, part 1

- Subchapter S

12. You loaned your roommate $4,500 for next semester's tuition. Your roommate promised to pay you back next summer from his summer employment. However, next summer, you realized that your roommate never found a job, but vacationed all summer in Europe. He e-mails you and informs you of his inability to pay off his debt. Can you claim any tax deduction? Focus primarily on the Internal Revenue Code for your research.

13. Use a tax service to find the definition of a material adviser in the Code. What type of list must the material advisor maintain? Give the authorities for your answers, using proper citation format.

14. Which Treasury Regulation provides rules for foreign-owned U.S. corporations and foreign corporations engaged in a trade or business within the United States (reporting corporations)? What IRS form is a reporting corporation required to file that relates to reportable transactions with a related party?

15. Determine the number of Treasury Regulations issued for each of the following Code sections 101, 183 and 385. Provide a citation to the last Regulation for each Code Section.

Using the Code

16. What deduction does § 162(a)(2) specifically authorize? What Code provision in another section disallows some of those deductions? Explain.

17. What is the penalty provided under Code Section 6662(b)(2)? Where in that Code section is that penalty defined? Explain the definition in your own words.

18. Determine whether employer contributions to employees' health and accident plans create gross income for the employee. Give the answer and describe the process used to find the answer, including the tax research database used, the successful method of search, and the relevant provision within the applicable code sections.

Using Treasury Regulations

19. Examine Treas. Reg. § 1.183-2. What Code section and language within that Code section does the Treasury Regulation interpret? What does the Treasury Regulation state are the nine relevant factors?

20. Find the Treasury Regulation that determines whether educational expenses can qualify as deductible business expenses. Give the citation for the general rule within that regulation.

21. Assume Sally is a professor who has a PhD in accounting and teaches tax courses. She decides that it would help her teaching to earn a law degree with a heavy emphasis on tax classes. Can she deduct the cost of the tax courses offered as part of her law degree? Explain and cite to specific provisions in the Code and Treasury Regulations.

Locating Cases

22. Locate Ballard v. Commissioner, 544 U.S. 40; 95 AFTR 2d 2005-1302 (2005). What was the main issue before the Supreme Court? What did the Supreme Court do with the appellate court's decision?

23. Find and read a Tax Court regular decision that discusses whether hair transplants are deductible medical expenses. Give the official citation to the case. What did the Tax Court hold? If a case with similar facts were decided today, would the Tax Court reach a similar conclusion? Explain.

Locating Revenue Rulings

24. Locate Revenue Ruling 2003-25, identify the topic, and find the date of the Revenue Ruling. What is the applicable Code section?

25. Locate Revenue Procedure 2008-20, identify the topic, and find the date of the Revenue Procedure. What is the applicable Code section? What IRS tax form addresses the same topic?

Evaluating Different Sources

26. Assume that the taxpayer has a tax issue in which the only authority on point is the following: (a) an unfavorable circuit court of appeals case from the same circuit as the taxpayer's residence and (b) a favorable decision from a district court in another circuit. What does one advise the taxpayer?

27. Assume that the taxpayer has a tax issue in which the only authority on point is the following: (a) an article written by a famous tax lawyer that supports taxpayer's position and (b) a Revenue Ruling that does not support taxpayer's position. What does the researcher advise the taxpayer?

28. Assume that the taxpayer has a tax issue in which the only authority on point is as follows: (a) a private letter ruling that favors the taxpayer's position and (b) a Tax Court regular decision that opposes taxpayer's position. What does the researcher advise the taxpayer?

Conducting Tax Research and Documentation

29. Assume that your best friend has a full scholarship offer for playing football at the University of Colorado at Boulder. The scholarship covers tuition, dorm room, and meal costs at the university. Write a brief memo explaining the tax consequences of the scholarship, documenting the relevant authorities.

30. Assume that your older sister agrees to tutor you for a month in math. She normally charges clients $500 for similar services. In return, you agree to write a brief memo explaining the tax consequences to both you and your sister. You would normally charge $100 for your services. Write the issue.

31. What were the issue(s) involved in National Westminster Bank v. United States, 512 F.3d 1347; 101 AFTR2d 2008-490, 2008-1 USTC ¶50,14 (Fed. Cir. 2008)? What is the proper citation for the prior decision in this case?

32. Use a tax service, such as United States Tax Reporter, to answer the following questions:

- If your school provides an athletic scholarship to an athlete, does the athlete have gross income?

- Can the athlete deduct his or her expenses for such items as clothing, meals, and fitness camp?

33. Use the citator to update the decision in United States v. Textron Inc., 507 F. Supp. 2d 138 (D.R.I. 2007). Determine if any case has cited this decision or any subsequent decisions in this case. What topic does this important case address that impacts accountants?

34. Myrtle loaned Sven $150,000 for his gardening supplies company. A drought occurred during the year. Because Sven was unable to repay the loan, Myrtle accepted the following plan to extinguish Sven's debt. Sven is to pay cash of $3,000 and transfer ownership of the gardening property having a value of $80,000 and a basis of $60,000. Sven must also transfer stock with a value of $30,000 and a basis of $45,000. Find a relevant Treasury Regulation. Read Code Section 108 and James J. Gehl, 102 T.C. 74 (1994). Determine how much gross income Sven should report from the extinguishment of his debt.

APPENDIX

FIGURE 7A-1 CPA EXAM, REGULATION SECTION, TAX SIMULATION PROBLEM

EXAMPLE: In year two, the partnership paid Miller $30,000 for services rendered to the partnership. The payments qualified as a guaranteed payment. What Code section and subsection provide that payments made to a partner for services rendered to a partnership are considered as made to one who is not a member of the partnership for purposes of Section 61(a) under the Research/Authoritative Section 162(a)?

Discussion: Search for “guaranteed payment” in the Code and discover § 707(c). Literature tab and “Sec. 707. Transactions between partner and partnership (c) Guaranteed payments

To the extent determined without regard to the income of the partnership, payments to a partner for services or the use of capital shall be considered as made to one who is not a member of the partnership, but only for the purposes of Section 61(a) (relating to gross income) and, subject to Section 263, for purposes of Section 162(a) (relating to trade or business expenses).”