Fraud Investigative Techniques

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After completing this chapter, you should understand:

- The definition of fraud.

- Different types of fraud.

- The components of the fraud triangle.

- The utilization of ACL and i2 Analyst Notebook in fraud investigations.

- An overview of a fraud examination and business investigation.

- The use of computer technology in fraud examinations/investigations.

Perhaps a client requests your help to determine if evidence exists of vendor kickbacks to certain employees in the purchasing department. Possibly a company's legal counsel has hired you to determine whether an officer of the company has any hidden assets as a result of an embezzlement scheme he or she carried out. Maybe you need to conduct background checks (due diligence checks) on potential strategic partners of a proposed joint venture. Sound like interesting assignments? These are a few examples of value-added forensic accounting services offered by accounting firms to their clients. Other common fraud auditor/examiner engagements in relation to an audit client could include the following:

- Providing assistance to the audit team in assessing the risk of fraud and other illegal acts.

- Providing assistance to the audit team in investigating potential fraud or other illegal acts.

- Conducting fact-finding forensic accounting studies of alleged fraud that could include bribery, wire fraud, securities fraud, money laundering, retailfraud, ortheft of intellectual property.

- Conducting due diligence studies that could include public record checks or background checks on individuals in a hiring situation or on entities in a potential acquisition.

- Consulting as to the implementation of fraud prevention, deterrence, and detection programs.

These examples of fraud engagements demand that the investigator possess unique research skills in addition to the traditional skills presented in the previous chapters of this book.

QUICK FACTS

Forensic accounting is the use of accounting in a court of law.

In addition to the typical accounting, auditing, and tax services rendered by accountants, the profession is rapidly moving into other value-added services known as fraud investigation (or litigation support) or the broader, more comprehensive term forensic accounting. The terms forensic accounting and litigation support generally imply the use of accounting in a court of law. Thus, the services of an accountant in a fraud investigation or court case are often referred to as forensic accounting or litigation support services.

Fraud is a major problem for most organizations. Stories about fraud often appear in newspapers and business periodicals. A review of such articles reveals that fraud is not perpetrated only against large organizations. One report in a business magazine has estimated that 80 percent of all crimes involving businesses are associated with small businesses. Although the full impact of fraud within organizations is unknown, various national surveys have reported that annual fraud costs to U.S. organizations exceed $900 billion (or 7 percent of their revenues) and are increasing.

RESEARCH TIPS

Develop fraud examination skills through education and experience.

Fraud examinations and background (due diligence) checks are not easy tasks. One must have the proper training, skills, and experience to conduct a successful fraud investigation. Many fraud investigators currently working in CPA firms obtained their experience working with various federal and local agencies, such as the IRS, FBI, or various levels of police work. Others obtained their fraud examination skills by attending conferences or seminars conducted by organizations such as the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners.

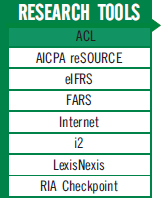

This chapter presents a basic overview of fraud and common red flags that may indicate its occurrence. Additionally, the chapter explains the basic steps of a financial fraud examination and the investigative techniques a forensic accountant may use. Because no two fraud investigations are alike, this chapter will provide a heightened awareness of the environment of fraud and present basic techniques for a fraud investigation. Also, with advances in technology, fraud examination is increasingly becoming more high tech. Thus, the chapter will highlight the use of computer software and the Internet as tools in fraud investigations. Discussion will focus on two major software products (ACL and i2's Analyst Notebook) that are utilized in fraud investigations.

DEFINITION OF FRAUD

In simplest terms, fraud is commonly defined as intentional deception, or simply lying, cheating, or stealing. Black's Law Dictionary defines fraud as:

A generic term, embracing all multifarious means which human ingenuity can devise, and which are resorted to by one individual to get advantage over another by false suggestions or by suppression of truth. It includes all surprise, trickery, cunning, dissembling, and any unfair way by which another is cheated.

Concern about fraud applies to investors, creditors, customers, government entities, and others. Major perpetrators of financial statement fraud such as Enron, Sunbeam, WorldCom, and others have raised the public's awareness of the importance of fraud prevention and detection.

Laws that relate to fraud are often complex. The fraud examiner must become aware of the different types of fraud and will often require the legal assistance of an attorney. However, the different fraud-related laws have a common legal definition. As defined by the U.S. Supreme Court, fraud includes the following elements:

- A misrepresentation of a material fact

- Known to be false

- Justifiably relied upon

- Resulting in a loss

QUICK FACTS

Fraud is the misrepresentation of a material fact, known to be false, justifiably relied upon, resulting in a loss.

Thus, a fraud examination involves various procedures of obtaining evidence relating to the allegations of fraud, conducting interviews of selected witnesses and related parties, writing reports as to the findings of the examination, and, in many cases, testifying in a court of law as to the findings. A sufficient reason or suspicion (predication) is the basis for beginning a fraud examination. Often, this predication is based upon circumstantial evidence that a fraud has likely occurred. An employee complaint or unusual or unexplained trends in financial ratios may raise a suspicion that something is wrong. The fraud examination is conducted to prove or disprove the allegations.

TYPES OF FRAUD

Statement on Auditing Standards No. 99, “Consideration of Fraud in a Financial Statement Audit,” distinguishes two categories of financial statement fraud: fraudulent financial reporting and misappropriation of assets.

QUICK FACTS

Fraud consists of fraudulent financial reporting and misappropriation of assets.

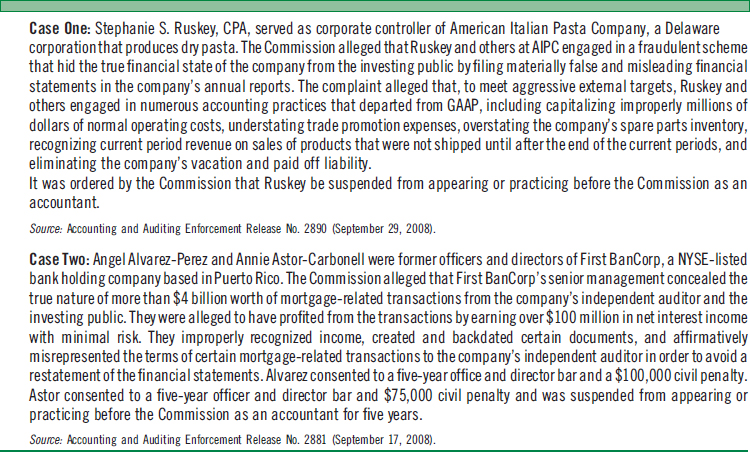

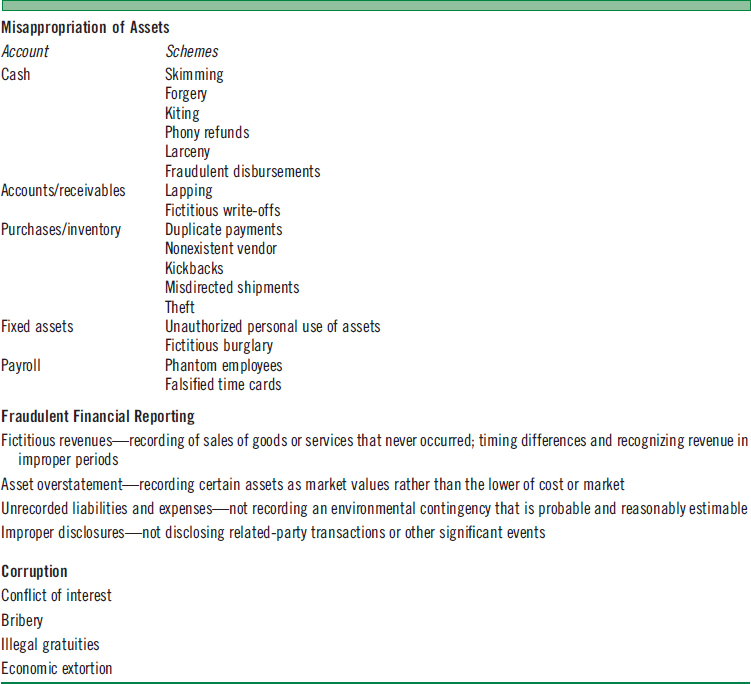

The first category of fraud, fraudulent financial reporting, is usually committed by management in order to deceive financial statement users. Thus, fraudulent financial reporting (management fraud) refers to actions whereby management attempts to inflate reported earnings or other assets in order to deceive outsiders. Examples of management fraud would include overstating assets/revenues, price fixing, contract bidding fraud, or understating expenses/liabilities in order to make the financial statements look better than they really are. Figure 10-1 presents details of two examples of enforcement actions by the SEC relating to management fraud. Fraudulent financial reporting is generally the most costly type of fraud.

The second category of fraud, misappropriation ofassets, is more commonly known as employee fraud. Misappropriation of assets refers to actions of individuals whereby they misappropriate (steal) money or other property from their employers. Various employee fraud schemes could include embezzlement, theft of company property, kickbacks, and others as listed in Figure 10-2. Misappropriation of assets is generally the most common type of fraud.

FIGURE 10-1 EXAMPLES OF MANAGEMENT FRAUD

FIGURE 10-2 COMMON EXAMPLES OF FRAUD ACTIVITIES

One common categorization of fraud is by industry classification, such as financial institution fraud, health care fraud, or insurance fraud. Another classification of fraud uses six types:1

RESEARCH TIPS

Approach each fraud investigation in a systematic manner.

- Employee embezzlement: Fraud in which employees steal company assets either directly (stealing cash or inventory) or indirectly (taking bribes or kickbacks).

- Management fraud: Deception by top management of an entity primarily through the manipulation of the financial statements in order to mislead users of those statements.

- Investment scams: The sale of fraudulent and often worthless investments, for example, telemarketing and Ponzi scheme frauds.

- Vendor fraud: Fraud resulting from overcharging for goods purchased, shipment of inferior goods, or nonshipment of inventory even when payment has been received.

- Customer fraud: Fraud committed by a customer by not paying for goods received or deceiving the organization in various ways to get something for nothing.

- Miscellaneous fraud: A catch-all category for frauds that do not fit into one of the previous five categories, for example, altering birth records or grade reports.

Although there are many different types and categories of fraud, a fraud examiner should approach each engagement in a systematic manner, as explained in this chapter.

THE FRAUD TRIANGLE

Why do individuals commit fraud? Probably the most common reason is that the perpetrators are greedy and believe that they will not get caught. Various researchers, including criminologists, psychologists, sociologists, auditors, police detectives, educators, and others have studied this issue. They have concluded that three basic factors determine whether an individual might commit fraud. These three factors comprising the fraud triangle include (1) motivation (perceived pressure or incentive), (2) perceived opportunity, and (3) rationalization.2 All three elements are generally present in the typical case of fraud.

The first element of the fraud triangle is motivation based on perceived pressure or incentive to commit a fraud. An individual's motivation can change due to external forces. An individual who is honest one day might commit fraud the next day due to external pressures. These pressures include financial pressures, vices, and work-related pressures. Typical financial pressures include excessive debt resulting from unexpected high medical bills, uncontrolled spending with credit cards, lifestyle beyond one's means, or outright greed. Vices may include addiction to gambling, drugs, or alcohol. The individual having a vice is sometimes motivated by this pressure to commit a fraudulent act in order to support his or her addiction. Work-related pressures could include not receiving desired job recognition, being overworked and underpaid, or not getting an expected promotion. A formerly honest individual may turn to fraud in order to get even with his or her employer.

QUICK FACTS

The fraud triangle consists of motivation (pressure or incentive), perceived opportunity, and rationalization.

The motivation based on perceived pressure or incentive for top management to commit financial statement fraud (management fraud) may include obtaining a bonus or stock option based on the company's financial results, the company's stock price, or meeting regulatory requirements. Similarly, dramatic changes in the organization, such as reengineering or a potential merger, can lead to uncertainty as to the future. This may motivate an individual to become dishonest in order to survive within the organization.

The second element of the fraud triangle is perceived opportunity. All employees have opportunities to commit fraud against their employers, suppliers, or other third parties, such as the government. Perceived opportunity is often driven by the access an individual has to the entity's assets or financial statements, the skill of the individual in exploiting the opportunity to commit fraud, and, in certain cases, the individual's seniority or trust within the organization. Many corporate frauds have occurred due to breaches of trust by employees and managers to whom access privileges were granted. If an individual believes that the opportunity exists to commit a fraud, conceal the fraud in some way from others, and avoid detection and punishment, the probability of the individual committing fraud increases. When an individual's professional aspirations are being met, the individual is generally content. However, when those aspirations are not met, unconventional measures that may include fraud are sometimes pursued.

Conditions (red flags) that may provide the opportunity for fraud include:

RESEARCH TIPS

Examine the fraud probability to plan the fraud investigation.

- Negligence on the part of top management in enforcing ethical standards or disciplining an individual who commits a fraud.

- Major changes in the entity's operating environment.

- Nonenforcement of mandatory vacation time for employees, preventing others from filling in during absences.

- Lack of supporting documentation for transactions.

- Lack of physical safeguards over assets.

QUICK FACTS

Effective internal controls reduce the opportunity for fraud.

Internal control is an important factor in limiting fraud. The fraud examiner must pay attention to the entity's internal controls and evaluate the weaknesses or red flags that provide the opportunity for fraud.

The third element of the fraud triangle is an individual's rationalization for the actions taken. If an individual can rationalize questionable actions as not being wrong, he or she might justify any improper behavior in his or her mind. Common rationalizations for fraud activity include such statements as:

- “I work long hours and am treated unfairly by my employer. The company owes me more.”

- “I will use the funds only formy current financial emergency and will pay them back later.”

- “The federal government foolishly wastes my money, so I will not report my extra income this year on my tax return. Besides, no one gets hurt.”

What the individual is attempting to do is to rationalize away the dishonesty of any wrongful action.

Individuals use many other rationalizations when committing fraud. However, an important factor, which the fraud examiner will evaluate, in minimizing illicit actions is an individual's personal integrity. An individual's strong personal standards of ethics can offset the temptation to rationalize the fraud activity. The tone set by top management as to proper ethical conduct can have a major impact on actions taken by employees.

Most frauds result when the three elements of the fraud triangle occur in combination: motivation (pressure or incentive), opportunity, and rationalization. If an organization is able to control or eliminate any of the three elements of the fraud triangle, the likelihood for fraud decreases. Knowledge of these three elements provides the fraud examiner with a better understanding of different approaches to take in the investigation.

Fraud comes in many forms. The forensic accountant must tailor the fraud examination to the specific circumstances. Following is an overview of a typical financial statement fraud examination.

OVERVIEW OF A FINANCIAL STATEMENT FRAUD EXAMINATION

RESEARCH TIPS

Understand the characteristics and types of fraud.

Over the years, independent auditors have often not met the expectations of third parties in detecting material fraud when auditing financial statements. Fraud auditing focuses on the detection and prevention of fraud. The fraud auditor should possess the skills of a well-trained auditor combined with those of a criminal investigator.

To further clarify the auditor's responsibility to uncover fraud in a financial statement, SAS No. 99 provides guidance. The auditor has a responsibility to plan and perform the audit in order to obtain reasonable assurance that the financial statements are free of material misstatement, whether caused by error or fraud. Therefore, the auditor/fraud examiner must understand the characteristics and types of fraud, be able to assess fraud risks or red flags, design an appropriate audit, and report the findings on possible fraud to management or the appropriate levels of authority.

Assessing the risk of material misstatement of the financial statements due to the possibility of fraud is a critical part of the first step. The assessment should include attempts to answer the following questions: What types of fraud risk exist? What is the actual and potential exposure to the fraud? Who are the perpetrators? How difficult is it to identify and prevent the fraud? What is the company doing to prevent fraud now? How effective are these measures? This risk assessment aids the auditor in designing the audit program and audit procedures to perform.

In conducting the risk assessment of material misstatement due to fraud, the auditor evaluates fraud risk factors (red flags) that relate to the two basic categories of financial statement fraud: fraudulent financial reporting and misappropriation of assets. A fraud risk factor is a characteristic that provides a motivation or opportunity for fraud or an indication that fraud may have occurred. The risk factors that relate to financial reporting fraud can be placed in the following three groups:

RESEARCH TIPS

Examine one's incentives, pressures, opportunities, and attitudes to identify potential fraud.

- Incentives/pressures: This group of risk factors relates to the financial stability or profitability of the entity, excessive pressure on management or operating personnel to meet expectations of third parties or financial targets, or a case where the personal situation of management or the board of directors is threatened by the entity's financial performance. Examples of specific red flags include a high degree of competition or market saturation along with declining profit margins, perceived or real adverse effects of reporting poor financial results, or personal guarantees by management or board members for debts of the entity.

- Opportunities: These factors relate to aspects of the industry or the entity's operations that provide the opportunity to engage in fraudulent financial reporting. Examples include significant or highly complex transactions, major operations conducted across international borders, or deficiencies in internal controls.

- Attitudes/rationalization: This category of risk factors reflects the tendency by board members or management to justify or rationalize their motives to commit fraudulent financial reporting. Examples of red flags include ineffective communication or enforcement of ethical standards and excessive interest by management in maintaining or increasing the entity's earnings trend.3

Risk factors relating to misstatements arising from the misappropriation of assets are classified into two groups: susceptibility of assets to misappropriation, which relates to the nature of the organization's assets and the probability of theft; and controls, which relate to the lack of measures for preventing or detecting the misappropriation of assets. Examples of red flags for the susceptibility of assets include large amounts of cash on hand; easily convertible assets, such as bearer bonds or diamonds; and lack of ownership identification of fixed assets that are very marketable.

QUICK FACTS

Red flags alert the auditor to potential fraud.

Although fraud is usually concealed, the presence of risk factors (red flags) may alert the fraud auditor to the potential for fraud within the company. If such factors exist and a risk assessment warrants, the auditor should discuss them with management and/or legal counsel. If the conclusion reached is that fraud is likely, a fraud examination would commence. The basic steps of the fraud examination are as follows:

- Identify the issue/Plan the investigation.

- Gather the evidence/Complete the investigation phase.

- Evaluate the evidence.

- Report findings to management/legal counsel.

Step One: Identify the Issue/Plan the Investigation

RESEARCH TIPS

Identify the fraud issue and create a hypothesis answering when, how, and by whom.

Based upon the circumstances indicating the possibility of fraud, the client and/or the client's legal counsel would usually instruct the fraud examiner to conduct a fraud examination. Management's suspicions as to the possibility of fraud could come from a number of sources. Employees may have observed improprieties committed by fellow employees or observed an employee's lifestyle that is inconsistent with his or her income. Issues may arise from an internal or external audit that has identified missing documents. Not all suspicions result in a finding of fraud, but, by pursuing the evidence and anomalies, the fraud examiner can make a reasoned determination as to its existence. If fraud exists and is not pursued, it will probably continue and more likely increase over time. Based upon the circumstantial evidence, the fraud examiner would create a hypothesis as to when the potential fraud occurred, how it was committed, and by whom.

Step Two: Gather the Evidence/Complete the Investigation Phase

Although different investigation methods exist, the objective of the investigation phase is to gather appropriate evidence in order to determine whether a fraud has occurred or is occurring. Investigations are often contentious and generate a great deal of uneasiness for all parties involved. Each investigation is different, and the suspects and witnesses will often react differently. One mistake in the investigation can jeopardize the entire process.

Also included in the investigation phase is the identification of resources to utilize in the investigation. The fraud examiner needs to know what resources are available: primary, secondary, or third parties. Various types of resources are discussed later in the chapter.

The investigation technique used will often depend on the type of evidence the fraud examiner is attempting to gather. One approach is to classify the evidence into four types with the related investigative techniques to gather the evidence as follows:4

QUICK FACTS

The investigative technique used often depends on the type of evidence sought.

| Type of Evidence | Investigative Technique |

|

Examination of documents, searches of public records, searches of computer databases, analysis of net worth, or analysis of financial statement Interviewing, interrogations, or polygraph tests Physical examination (counts/inspections) or surveillance (close supervision of suspect during examination period) Use of forensic expertise |

Two examples of gathering evidence as to the existence of fraud are presented below:

Case One: Management has experienced lower profit margins than expected. In this investigation, the fraud examiner might review inventory procedures to determine whetheremployees are stealinginventory. The investigation might identify shrinkage in the actual counts of high-dollar inventory items, and a review of surveillance records may show whether anyone has removed inventory during off hours.

Case Two: Aco-workerhas reported that an employee appears to be livingwell above his known means. In such a case, the fraud investigator might review payment records to determine whether sales proceeds were diverted into an employee's personal account. A net worth analysis can also identify inconsistencies, and a review of the suspect's brokerage statements (with legal permission) may show whether the deposit dates correspond to the dates when questionable business transactions occurred.

The investigation phase of the examination requires strong analytical skills. These skills are important in the analysis of the financial information and other data for any trends or anomalies.

QUICK FACTS

Fraud investigations identify the issues, gather the evidence, evaluate the evidence, and report the findings.

In gathering testimonial evidence, interviewing skills are critical for the fraud examiner. Interviewing skills require an ability to extract testimonial evidence from collaborators, co-workers, or others related to the case, as well as the suspect, in hopes of obtaining a confession. Fraud-related interviews are carefully planned question-and-answer sessions designed to solicit information relevant to the case.

Also, information technology skills are required in order to search public records and other electronic databases in the gathering of evidence for the investigation. The use of computer databases and software in evidence gathering for a fraud investigation is discussed later in this chapter.

Step Three: Evaluate the Evidence

After completing a thorough investigation, the fraud examiner will evaluate the evidence in order to determine whether the fraud has occurred or is still occurring. One can draw sound conclusions only if the information was properly collected, organized, and interpreted. Once fraud is discovered, the fraud examiner attempts to determine the extent of the fraud. Was it an isolated incident? Was there a pattern connecting the incidents? When did the fraud begin? By identifying how long and to what extent the fraud occurred, the investigator may be able to provide critical information to help the client recover missing funds from the perpetrator or obtain reimbursement from an insurance company.

RESEARCH TIPS

Ask many questions in a fraud examination to determine the extent of the fraud.

Step Four: Report Findings to Management/Legal Counsel

Upon completing the evaluation of the evidence, the fraud examiner needs to document the results of the investigation and prepare a report on the findings. The report should use the writing concepts discussed in Chapter 2. Any report should use coherent organization, conciseness, clarity, Standard English, responsiveness, and a style appropriate to the reader.

At times, the client's legal counsel may request that the fraud examiner serve as an expert witness in a court case. A fraud examiner might win or lose a court case against a perpetrator depending upon the accuracy and technical rigor of the examiner's investigation and report. However, the fraud examiner's report needs to avoid rendering an opinion as to the guilt or innocence of the suspect. The report should state only the facts of the investigation and the findings. The report should present answers as to when the fraud occurred, how it was committed, and by whom.

Because fraud investigations are considered litigation support services, which are considered consulting services, the CPA/fraud investigator needs to adhere to professional standards during the investigation, as well as in developing the report. Relevant standards and guidance are issued by the AICPA's Management Consulting Services Committee and related subcommittees.

BUSINESS INVESTIGATIONS

A business or due diligence investigation is sometimes performed by professional accountants to help management minimize business risks. At times, a client may need help to verify information about an organization before entering into a joint venture or corporate merger. Or perhaps the client needs a background information check before hiring a new corporate officer or other employee. In other situations, the client may need to know about any related parties associated with the corporation or the reputation of a potential new vendor. In each of these examples, a business or individual background investigation might prove valuable in obtaining desirable information for managing business risks.

A “documents state of mind” is needed in most types of investigative work, Many types of documents, or paper trails, can be used by the investigator to gather facts about the issue under investigation. Such documents are classified as either primary or secondary sources. A typical secondary source would be a newspaper article about a company acquiring a subsidiary or doing business in a certain country.

RESEARCH TIPS

Develop a “documents state of mind” to show a paper trail.

Primary documents are readily available in many types of investigations. For example, if one is attempting to gather background information on a new corporate executive, typical primary sources would include voter registrations, tax records for property ownership, details of civil and criminal lawsuits, and divorce and bankruptcy records. Corporations have similar types of paper trails. For example, an entity's articles of incorporation are roughly equivalent to an individual's birth certificate.

FIGURE 10-3 INVESTIGATIVE TECHNIQUE: “WORKING FROM THE OUTSIDE IN”

In gathering background information, the investigator typically follows a technique referred to as “working from the outside in.” This technique is depicted in the form of concentric circles, with the larger circle representing the secondary sources, as illustrated in Figure 10-3. The middle circle contains the primary sources that often substantiate the secondary information. The inner circle could include personal interviews for facts concerning the target or the issue under investigation. In many investigations, the investigator needs to use creativity in gathering and analyzing the data.

COMPUTER TECHNOLOGY IN FRAUD INVESTIGATIONS

In the Information Age, fraud potential is wider in scope. However, new tools and techniques are available to combat this expansion of fraud. Uncovering signs of fraud among possibly millions of transactions within an organization requires the fraud examiner to use analytical skills and work experience to construct a profile against which to test the data for the possibility of fraud. Three important tools for the fraud examiner are data mining software, public databases, and the Internet.

Data Mining Software

Data mining software is a tool that models a database for the purpose of determining patterns and relationships among the data. This tool is an outgrowth of the development of expert systems. Computer-based data analysis tools can prove invaluable in searching for possible fraud. From the analysis of data, the fraud examiner can develop fraud profiles from the patterns existing within the database. Through identifying and understanding these patterns, the examiner may uncover fraudulent activity. The use of data mining software also provides the opportunity to set up automatic red flags that will reveal discrepancies in data that should be uniform. Some of the common features of data mining software include the following:

- Sorting: Arranging data in a particular order such as alphabetically or numerically

- Occurrence selection: Querying the database to select the occurrences of items or records in a field

- Joining files: Combining selected files from different data files for analysis purposes

- Duplicate searches: Searching files for duplication, such as duplicate payments

- Ratio analysis: Performing both vertical and horizontal analyses for anomalies

Following is a brief description of some of the more common commercial data mining software products used by fraud examiners.

WizRule This software package is used for many different applications, such as data cleaning (searching for clerical errors) or anomaly detection in a fraud examination. The program is based on the assumption that, in many cases, errors are considered as exceptions to the norm. For example, if Mr. Johnston is the only salesperson for all sales transactions to certain customers, and a sales transaction to one of the customers is associated with salesperson Mrs. Allen, the software could identify the situation as a deviation or a suspected error.

QUICK FACTS

Data mining examines patterns and relationships among the data.

WizRule is based on a mathematical algorithm that is capable of revealing all the rules of a database. The main output of the program analysis is a list of cases found in the data that are unlikely to be legitimate in reference to the discovered rules. Such cases are considered suspected errors.

Use software packages that utilize various mathematical algorithms to examine the data.

Financial Crime Investigator This program offers a systematic approach for investigating, detecting, and preventing contract and procurement fraud. The software, using artificial intelligence, provides instructions on how to query databases to find fraud indicators and match them to the appropriate fraud scheme. It provides a detailed work plan to investigate each scheme, converts probable schemes to the related criminal offenses, outlines an investigative plan for each offense based on the elements of proof, and generates interview formats for debriefing anonymous informants for each contract fraud scheme.

IDEA (Audimation Services, Inc.) This product is a powerful generalized audit software package that allows the user to display, analyze, manipulate, sample, or extract data from files generated by a wide variety of computer systems. The software provides the ability to select records that match one's criteria, check file totals and extensions, and look for gaps in numerical sequences or duplicate documents or records. The investigator can conduct fraud investigations; perform computer security reviews by analyzing systems logs, file lists, and access rights; or review telephone logs for fraudulent or inappropriate use of client facilities.

Monarch This software program allows the investigator to convert electronic editions of reports from programs such as Microsoft Access into text files, spreadsheets, or tables. Monarch can then break this information into individual reports for analysis.

ACL for Windows ACL Services Ltd., the developer and marketer of ACL for Windows, is considered the market leader in data inquiry, analysis, and reporting software for the auditing profession. ACL's clients include many of the Fortune 100 companies, governmental agencies, and many of the largest international accounting firms. In the software category of fraud detection and prevention, ACL for Windows is the most commonly used software package. An educational version is included in the enclosed CD.

This software product allows the fraud examiner to perform various analytical functions without modifying the original data. The software can sort data on multiple levels as well as locate numerical gaps in the sequencing of data. Graphical display options allow the investigator to create graphs from the Histogram, Stratify, Classify, and Age commands. ACL is very beneficial in fraud detection due to its ability to quickly and thoroughly analyze a large quantity of data in order to highlight those transactions often associated with fraudulent activity.

QUICK FACTS

Software can often assist in highlighting transactions often associated with fraudulent activities.

As a world leader in data inquiry, analysis, and reporting software, ACL is very effective in such areas as identifying trends and bringing potential problem areas, highlighted errors, or potential fraud to the auditor/fraud examiner's attention by comparing files with end-user criteria and identifying control concerns. In the specific area of fraud detection, ACL can identify suspect transactions by performing such tests as matching names between employee and paid vendor files, identifying vendor price increases greater than an acceptable percent, identifying invoices without a valid purchase order, and identifying invoices with no related receiving report. As the forensic accountant attempts to sort through a massive volume of data in order to detect the possibility of fraud, ACL is a major software product available for the fraud examiner. Figure 10-4 shows the opening screen for ACL software.

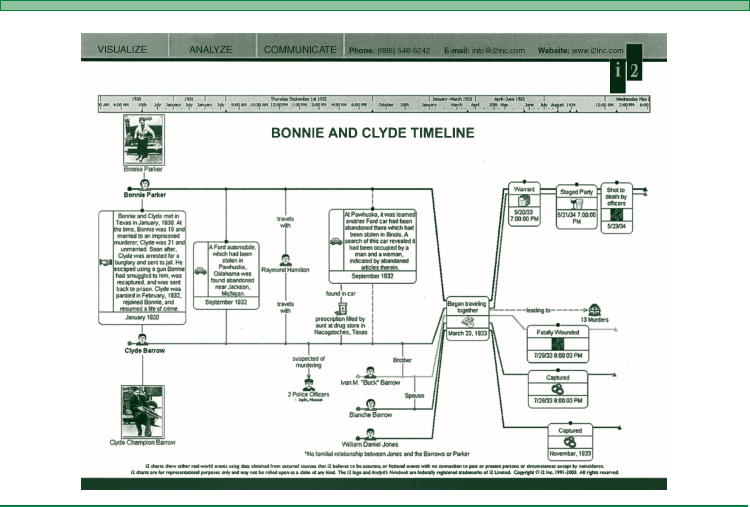

Analyst's Notebook This software package, developed by i2 Inc., is a visual investigative analysis product that assists investigators by uncovering, interpreting, and displaying complex information in easily understood charts. In many investigations, one must carefully analyze large amounts of multiformatted data gathered from various sources. The software provides a range of visualization formats showing connections between related sets of information and, in chart form, revealing significant patterns in the data. The software is excellent for extracting sections from large and complex investigation charts in order to produce smaller, more manageable presentation charts.

FIGURE 10-4 OPENING SCREEN OF ACL SOFTWARE

A visual presentation is a powerful tool to use in discussing the case with legal counsel and in presenting findings in court. For example, if the fraud examiner has a complex investigation chart of individuals and locations of suspects, and legal counsel is interested in one particular individual, the software can immediately produce a smaller chart showing only the information relating to that one individual. Figure 10-5 provides an example of i2's charting capabilities with respect to a drug cartel investigation.

In a fraud investigation, the Analyst's Notebook can aid the fraud examiner in developing building blocks that support the key issues of how and why. The software can help manage the large volume of information collected; help in understanding the information by providing a link analysis to build up a picture (chart) of the individuals and organizations involved in the fraud; help in the examination of the fraudsters' actions by developing a timeline analysis as to the precise sequence of events in the fraud case; and help in the discovery of the location of the stolen money or assets. Figure 10-6 provides an example of a timeline chart of the famous Bonnie and Clyde investigation.

RESEARCH TIPS

Use Analyst's Notebook to help chart your fraud investigation.

Typical investigations using the Analyst's Notebook include money laundering activities, securities fraud, credit card fraud, insurance fraud, and organized crime cases. Additional tools available to the fraud investigator from i2 Inc. include iBase and iBridge. iBase is a state-of-the-art database software tool that not only captures, but also controls and analyzes, multisource data in a secure environment. With iBase, one can quickly build a multi-user investigative database that can provide information in a unique visual format. iBridge serves as a connectivity solution that provides the user with a live connection to multiple databases throughout one's organization. It provides connectivity to a variety of relational databases for data retrieval and analysis by the fraud investigator.

FIGURE 10-5 I2'S CHART OF A DRUG CARTEL INVESTIGATION

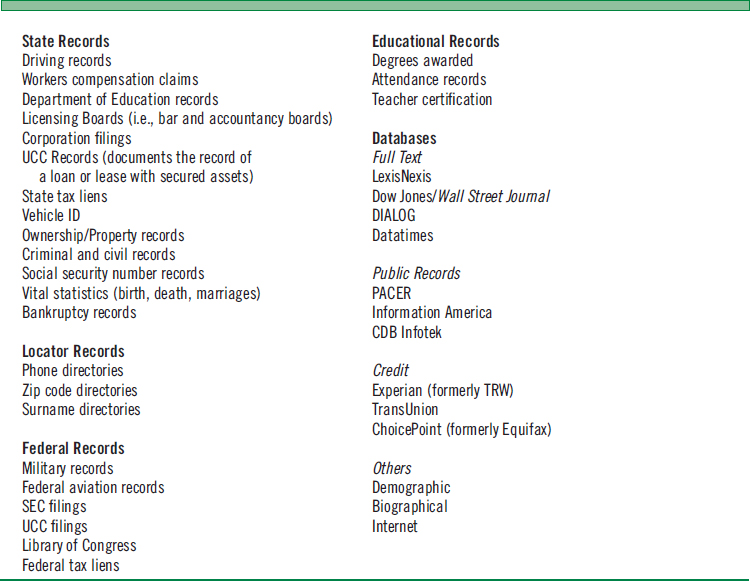

Public Databases

Given the enormous volume of public records (including information sold to the public for a fee), in certain cases, the fraud examiner or investigator may not need anything else in gathering evidence. These public databases include, among other information, records of lawsuits, bankruptcies, tax liens, judgments, and property transactions from all over the United States and, in certain cases, from around the world. If the examiner cannot locate the information via computerized databases, he or she can still locate the necessary information by personally visiting courthouses, recorder's offices, or city halls.

The fraud examiner/investigator relies heavily on public records/databases. Because these records are in the public domain, there are usually no restrictions in accessing the information. Business intelligence literature commonly cites that 95 percent of spy work comes from public records/databases. Additional reasons for utilizing public records include the quick access time and the inexpensive search costs.

FIGURE 10-6 I2'S TIMELINE CHART OF THE “BONNIE AND CLYDE” INVESTIGATION

Some of the commonly used public records/databases include courthouse records, company records, online databases, and the Internet. Figure 10-7 presents a summary listing (not all-inclusive) of typical records/files or databases available to the investigator.

Courthouse Records Every county has a courthouse and a place to file real estate records. In both small towns and large cities, lawsuits, judgments, and property filings are found at the courthouse. In addition to county records, the same types of records are filed at federal courts, which also contain bankruptcy filings. These records address the basic questions of a business investigation: Is the subject currently in a lawsuit? Are there unsatisfied judgments? Is there a criminal history? Has the subject filed for bankruptcy?

RESEARCH TIPS

Use public databases that include courthouse records, company records, online databases, and the Internet

The existence of these courthouse records tells the investigator something, but buried within the case jackets and docket sheets is even more information. Looking for financial information, the investigator can examine such items as the mortgage on a subject's home. Divorce filings and bankruptcy filings are business investigations in themselves. They contain records on assets and liabilities, employment histories, and pending suits.

Company Records The common starting point in many business investigations is public filings made with the SEC, accessible on the various databases at the SEC Web site. Unfortunately, the great majority of privately held companies need not file with the SEC. This leaves two primary sources for company information. First, Dun and Bradstreet compiles data on millions of companies. Experienced investigators recognize the shortcomings of these reports, but know that they make great starting points. Second, all businesses file some form of report in either the state or the county where they are located. Proprietorships and partnerships typically file local “assumed name,” “d/b/a,” or “fictitious name” filings. Corporations, limited partnerships, and limited liability companies (LLCs) file annual reports in their states of registration. These reports will typically identify the officers and registered agent of the company, but most reports will not list ownership data or financial information.

FIGURE 10-7 INVESTIGATIVE RESOURCES

RESEARCH TIPS

Examine company records and other relevant documents from online databases.

Other sources of company information supplement the various public records and courthouse records. Uniform Commercial Code filings (UCCs) and real estate filings can provide details missing in basic business filings. An investigator may tie an individual to a company because both the individual and the company are co-debtors in a secured agreement. Detailed financial information on private companies often can be gathered from litigation records over contracts, trade secrets, and other issues. Different regulatory bodies may have information on companies, even when they are closely held. State insurance commissions, for instance, have files for the public on companies that sell insurance in their states. Companies awarded government contracts also have to make certain information public. Investigators should try a variety of public records to acquire relevant information on the company under investigation.

Online Databases Many investigators use commercial databases to acquire the majority of their information. As described above, commercial databases give investigators the ability to quickly pull information from all over the world without alerting the subject. The speed and depth of commercial databases make them a must-have for business investigators.

Online databases come in four basic formats. The first type is the full-text database. Full text means that the database stores, for retrieval, the full text of articles. Several databases now have articles from newspapers and magazines from around the world. Databases also carry the full text of transcripts of television and radio broadcasts. LexisNexis, Dow Jones News Retrieval, and Datatimes are examples of full-text databases. Many online databases are now conveniently available on the Web. The online database world provides the majority of information now used by the business investigator.

QUICK FACTS

Online databases include full-text documents, public records, credit information, and other valuable information.

The second type of database is the public record database. Database companies provide access to many different types of courthouse records as well as company records. Access to federal litigation and bankruptcy records is obtainable through the PACER system. Major vendors of public record databases include Information America, CDB Infotek, and LexisNexis.

A third type of database is the credit and demographic database. The Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) restricts the use of consumer credit information, but credit bureaus offer data not covered by the FRCA. Other databases act as national phone books, providing names and addresses across the country. Credit bureaus include Experian (formerly TRW), Trans Union, and ChoicePoint (formerly Equifax). Suppliers of demographic data such as names and addresses include Metronet and DNIS.

Finally, there are databases that provide additional types of information. Vendors like Dialog and LexisNexis also provide company directories, abstracts, and biographical records such as “Who's Who.”

The Internet

Fraud examiners/investigators utilize the Internet beyond accessing commercial databases. Searching the Internet is generally not as precise as searching most commercial databases. Thus, investigators tend to stick with LexisNexis and Dialog. However, Internet online magazines often provide breaking news stories not covered elsewhere. Newsgroups and mailing lists contain raw (but often erroneous) data on companies. Finally, the first source of information on a company these days is often its own corporate Web site. For example, companies place detailed background information on themselves as well as profiles of their key executives on their Web sites.

Internet Web sites utilized by fraud examiners/investigators include KnowX, Switchboard, and others described in the following paragraphs.

KnowX (www.knowx.com) Many of the previously cited public documents are currently accessible via the Internet. KnowX, a LexisNexis company, is an online public record service. This Web site provides the fraud investigator with inexpensive searches to do background checks on a business, locate assets, and investigate for property values. Typical searches available include aircraft ownership records, a business directory, corporate records, date-of-birth records, lawsuits, real estate tax assessor records, stock ownership records, and watercraft ownership records.

Zoominfo.com (www.zoominfo.com) This Web site collates information from various Web sites through its software bots, also known as intelligent agents, which capture and match information to a particular person or company. You can search by company, person or industry. However, this information is generated from other Web sites and needs to be verified.

Other Web sites Other specific Internet sites related to fraud include:

- Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (www.acfe.com). This Web site provides information on fraud and the Certified Fraud Examiners Program.

- Online Fraud Information Center (www.fraud.org).

- Fraud Information Center (www.echotech.com/fmenu.htm).

FRAUD INVESTIGATION REGULATIONS

Many different types of information are available to fraud investigations. One must gather the information legally in order to provide the evidence in a court of law. Some federal acts that govern access to information are the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), and privacy laws that restrict the type of information that organizations may provide.

QUICK FACTS

Conducting a professional fraud investigation requires following the law.

The FOIA increased the availability of many government records. Typical information available under the FOIA includes tax rolls, voter registration, assumed names, real property records, and divorce/probate information. Information not available under the FOIA includes such items as banking records, telephone records, and stock ownership.

The FCRA regulates what information consumer reporting agencies can provide to third parties. Under the FCRA, an individual cannot obtain information about a person's character, general reputation, personal characteristics, or mode of living without notifying that person in advance. Thus, a fraud examiner/investigator should learn more about the legality of evidence gathered.

SUMMARY

As discussed in this chapter, fraud is a major risk to society. As fraud increases, businesses are turning to fraud examiners/investigators to help fight it. Therefore, professional accountants are offering additional services to clients in the area of forensic accounting or litigation support services related to the audit. Fraud examination steps include identifying the issues and planning the investigation, gathering the evidence in an investigation phase, evaluating the evidence, and reporting findings to entity management or legal counsel. Software and database tools are used to help the professional gather and organize the evidence for such engagements. Each fraud investigation is unique and requires strong critical thinking skills as it proceeds.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- Describe four different examples of fraud engagements.

- Define forensic accounting.

- Define fraud and identify four examples of fraud.

- What are the three components of the fraud triangle? Of what concern are they to the fraud examiner?

- What is a risk factor or red flag?

- Differentiate between management fraud and employee fraud.

- What are some risk factors associated with management fraud and employee fraud?

- Identify the basic steps of a fraud examination.

- Provide two examples of a business/due diligence investigation.

- Describe three computerized tools used by the fraud examiner/investigator.

- Explain the difference between data mining software and public databases.

EXERCISES

1. Access the KnowX Web site (www.knowx.com) and enter a free search. Discuss what you searched for and what you found. Provide two examples of how the fraud examiner/investigator can utilize this Web site.

2. Access Zoominfo.com and search for a business. What were your results?

3. Access the Fraud Information Center (www.fraud.org) and locate and describe three types of fraud reported by the Fraud Information Center.

4. Acquire information about the Bernie Madoff investment management scandal, as revealed in 2009. Integrate the theory presented in this chapter with the facts of the case to explain the scandal. Why were government investigators so slow to uncover this record-breaking $50 billion fraud?

5. Access a recently issued SEC Accounting and Auditing Enforcement Release related to a fraud action (www.sec.gov/divisions/enforce/friactions.shtml), and determine incentive(s)/pressure to commit the fraud, accounting issue(s), and the motive for the fraud.

6. Access the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners Web site (www.acfe.com) and complete the following:

- List three qualifications for becoming a CFE.

- List three items located in the ACFE's resource library.

7. Locate four Web sites on fraud and briefly describe the contents of the sites.

1 W. Steve Albrecht, Gerald W. Wernz, and Timothy L. Williams, Fraud: Bringing Light to the Dark Side of Business (Burr Ridge, Ill.: Richard D. Irwin, Inc., 1995).

2 More detailed discussion of the fraud triangle can be found in the following: G. Jack Bologna and Robert J. Lindquist, Fraud Auditing and Forensic Accounting, 2nd ed. (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1995); W. Steve Albrecht et al., Fraud Examination (Cincinnati: South-Western/Cengage, 2009); and Association of Certified Fraud Examiners, Fraud Examiners Manual, annual editions.

3 AICPA, SAS No. 99, “Consideration of Fraud in a Financial Statement Audit” (October 2002).

4 Albrecht et al., op. cit.