Chapter 14

International accounting

‘Whether we are ready or not, mankind now has a completely integrated financial and informational market place capable of moving money and ideas to any place on this planet in minutes.’

W. Wriston, Risk and Other Four-letter Words, p. 132, The Executive's Book of Quotations (1990), p. 150.

Learning Outcomes

After completing this chapter you should be able to:

- Explain and discuss the main divergent forces.

- Understand the macro and micro approaches to the classification of international accounting practices.

- Understand the accounting systems and environments in France, Germany, China, the UK and the US.

- Examine the convergent forces upon accounting, especially harmonisation in the European Union and standardisation through the International Accounting Standards Board.

Go online to discover the extra features for this chapter at www.wiley.com/college/jones

Go online to discover the extra features for this chapter at www.wiley.com/college/jones

Chapter Summary

- Global trade and investment make national accounting very constrictive.

- Divergent forces are those factors that make accounting different in different countries.

- The main divergent forces are: objectives, users, sources of finance, regulation, taxation, the accounting profession, spheres of influence and culture.

- Countries can be classified into those with macro and micro accounting systems.

- France and Germany are macro countries with tight legal regulation, creditor orientation and weak accounting professions.

- The UK and the US are micro countries, guided by the idea of faithful presentation, with influential accounting standards, an investor-oriented approach and a strong accounting profession.

- Internationalisation causes pressure on countries to depart from national standards.

- The three main potential sources of convergence internationally are the European Union, the International Accounting Standards Board through International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) and US standards.

Introduction

Increasingly, we live in a global world where multinational companies dominate world trade. The world's stock exchanges are active day and night. Accounting is not immune from this globalisation. There is an increasing need to move away from a narrow national view of accounting and see accounting in an international context. The purpose of this chapter is to provide an insight into these wider aspects of accounting. In particular, we explore the factors that cause accounting to be different in different countries, such as objectives, users, regulation, taxation and the accounting profession. Accounting in some important countries (France, Germany, the UK and the US) is also explored. Finally, this chapter looks at the international pressures for convergence towards one universal world accounting system. In essence, therefore, the aim of this chapter is to provide a brief overview of the international dimension to accounting.

Context

Perhaps surprisingly, given the variety of peoples and cultures throughout the world, the fundamental techniques of accounting are fairly similar in most countries. In other words, in most countries businesses use double-entry bookkeeping, prepare a trial balance and then an income statement (profit and loss account) and statement of financial position (balance sheet). This system of accounting techniques was developed in Italy in the fifteenth century and spread around the world with trade.

However, the context of accounting in different countries is very different and causes transnational differences in the measurement of profit, assets, liabilities and equity. The differences between countries are caused by so-called ‘divergent forces’, such as objectives, users, sources of finance, regulation, taxation, accounting profession, spheres of influence and culture. These divergent forces, which are examined in more detail in the next section, caused accounting in the UK to be different to that in, say, France or the US.

National Boundaries

‘National borders are no longer defensible against the invasion of knowledge, ideas, or financial data.’

Walter Wriston, Risk and Other Four-Letter Words, p. 133

Source: The Executive's Book of Quotations (1994), p. 202. Oxford University Press.

These international accounting differences caused few problems until the globalisation of international trade. However, with the rise of global trade and the erosion of national borders (see Soundbite 14.1), the variety of world accounting practices has been seen by many as a significant problem, particularly for multinational companies. There have been increasing pressures for the standardisation of accounting practices worldwide.

For large multinational companies, it is cheaper and easier to have just one set of world accounting standards. This is the aim of the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB). Meanwhile, within Europe there is pressure to harmonise accounting to create one set of Europe-wide standards. For European listed companies, the European Union (EU) has endorsed International Accounting Standards (IAS). These pressures for the harmonisation and standardisation of accounting are called ‘convergent forces’. In essence, therefore, these divergent and convergent forces pull accounting internationally in different directions. Large global corporations, such as GSK, Microsoft, Nokia, Toyota and Volkswagen, dominate world trade. As Real-World View 14.1 shows, the revenue of many of these corporations is greater than the gross domestic product of many countries. For example, the revenue of Wal-Mart stores and Royal Dutch Shell were greater than the GDP of countries such as Thailand, Denmark, Colombia and Venezuela. In fact only 28 countries in the world exceeded the revenue of Wal-Mart stores.

The World's Top Economic Entities in 2011

Source: Wikipedia 2011 countries by GDP from World Monetary Fund and Fortune, Global 2011 companies ranked by revenue.

Divergent Forces

Divergent forces are those factors that cause accounting to be different in different countries. These may be internal to a country (such as taxation system) or external (such as sphere of influence). There is much debate about the nature and identity of these divergent forces. For example, some writers exclude objectives and users. Each country has a distinct set of divergent forces and the relative importance of each divergent force varies between countries. These divergent forces are interrelated. The main divergent forces discussed in this chapter are shown in Figure 14.1. These divergent forces influence in particular a country's national practices.

(i) Objectives

The objectives of an accounting system are a key divergent force. There are two major objectives: economic reality, and planning and control. The basic idea behind economic reality is that accounts should provide a ‘true and fair’ view of the financial activities of the company. The UK holds this view. The US takes a similar view: ‘present fairly … in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP)’. However, in the US there is a stronger presumption than in the UK that following GAAP will present a fair view of the company's activities. The UK's ‘true and fair’ concept is basically linked to the underlying idea that the purpose of accounting is to provide users with financial information so that they can make economic decisions.

In contrast to economic reality, planning and control places more emphasis on the provision of financial information to government. Accounting in countries such as China, France and Germany is more concerned with collecting statistical and regularised information for comparability and planning. For example, in France accounting has traditionally been seen as promoting national economic and fiscal planning. In France and Germany, the concept of a true and fair view is incorporated in national law. Unlike in the UK, this is more narrowly interpreted as compliance with the regulations.

(ii) Users

Users and objectives are closely interrelated. Users are also linked closely to another divergent force, sources of finance. In some countries, such as the UK and the US, shareholders are the main users of accounts. In the UK, institutional investors (such as insurance companies and pension firms) dominate, while in the US the role of the private individual is comparatively more important. When shareholders dominate, the accounting system focuses on profitability and the income statement becomes the main financial statement. However, recently standard setters have moved towards a statement of financial position approach.

In other countries, such as France and Germany, the power of the shareholder is less. In France, for example, the users of accounting are more diverse, ranging from the government for economic planning, to the tax authorities for fiscal planning, to the banks. In Germany, the main users are the tax authorities and the banks. In France and Germany, the users are generally relatively more concerned about liquidity and the statement of financial position than in the UK and the US. However, in both France and Germany, as more multinational companies are listed, the power of the shareholder is increasing. Both countries use IFRS for listed companies. In China, there is a range of users which includes investors, but these are not the main focus of the accounting system.

Users

If the main users of accounts are banks rather than shareholders, how will that affect the items in the financial statements which they scrutinise?

Bankers essentially lend companies money and are concerned about two main things: loan security and loan repayments. They are, therefore, likely to focus on the statement of financial position, particularly on assets, gearing and liquidity. They will wish to make sure that any assets on which the loans are secured have not been sold or lost value. They will investigate the gearing ratios to see that the company has not taken on too many additional loans. In addition, they will scrutinise the amount of cash and the liquidity ratios to ensure that there is enough cash to pay the loan interest.

Shareholders invest their capital and look for a return. They will, therefore, principally be concerned with the income statement. In particular, they will look at earnings, earnings per share, dividends and dividend cover. They will wish to be assured that the company is profitable and will remain profitable.

(iii) Sources of Finance

A key question for any company is how to finance its operations. Apart from internally generated profits, there are two main sources: equity (or shareholder) finance and debt (or loan) finance. In some countries, such as the UK and the US, equity finance dominates. In other countries, for example, France and Germany, there is a much greater dependence on debt finance. The relative worldwide importance of the stock exchange (where equity is traded and raised) can be seen in Figure 14.2.

The presence of a strong equity stock market, such as in the US or the UK, leads countries to have an investor and an economic reality-orientated accounting system. There is a focus on profitability and the importance of auditing increases. By contrast, a strong debt market is historically associated with the increased importance of banks. Thus, Germany whose economy is larger than that of the UK has a much smaller stock market. As a consequence, much more of the funding for industry comes inevitably from loan finance.

(iv) Regulation

By regulation, we mean the rules that govern accounting. These rules are primarily set out by government as statute or by the private sector as accounting standards (see Chapter 10 for more detail on the UK). The balance and interaction between statutory law and standards within a particular country is often subtle. The regulatory burden is usually significantly greater for public listed companies than for smaller non-listed companies.

In the UK and the US, for example, accounting standards are very important. However, whereas in the UK there are Companies Acts applicable to all companies, in the US, the Securities Exchange Commission, an independent regulatory organisation with quasi-judicial powers, regulates the listed US companies. Other US companies are regulated by state legislation, which is often minimal.

In some countries, such as France and Germany, accounting standards are not so important. Indeed, France has no formal standard-setting body equivalent to the UK's Accounting Standards Board, while Germany only set up a standard-setting organisation in 1999. In France and Germany accounting regulation originates from the government: in Germany, by way of a Commercial Code and in France, by way of a comprehensive government manual for accounting. However, French and German listed companies use IFRS.

(v) Taxation

Strictly, the influence of taxation is part of a country's regulatory framework. However, as the relationship between accounting and taxation varies significantly between countries, it is discussed separately here. Essentially, national taxation systems may be classed as ‘independent’ of, or ‘dependent’ on, accounting. In independent countries, such as the UK, the taxation rules and regulations do not determine the accounting profit. There are, in effect, two profits (calculated quite legally!) – one for tax and the other for accounting. The US uses a broadly independent tax system. However, there is a curious anomaly. If US companies wish to lower their taxable profits, they can use the last-in-first-out (LIFO) method of inventory valuation (which usually values inventory lower than alternative inventory valuation methods, and thus lowers profits). (See Chapter 16 for a fuller discussion of LIFO.) However, these companies must also use this method in their shareholder accounts.

In France, Germany and China however, for individual companies accounting profit is dependent upon taxable profit. In effect, the rules used for taxation determine the rules used for accounting. Accounting, therefore, becomes a process of minimising tax paid rather than showing a ‘true and fair view’ of the company's financial activities. However, group accounts in France and Germany can be prepared using international principles as tax is calculated on individual company, rather than group accounts.

(vi) Accounting Profession

Accounting professions worldwide vary considerably in their size and influence. In the UK and US accountants play an important interpretive and judgemental role. Although accounting standards are independently set, qualified accounting professionals generally constitute the majority of the members of the accounting standards boards.

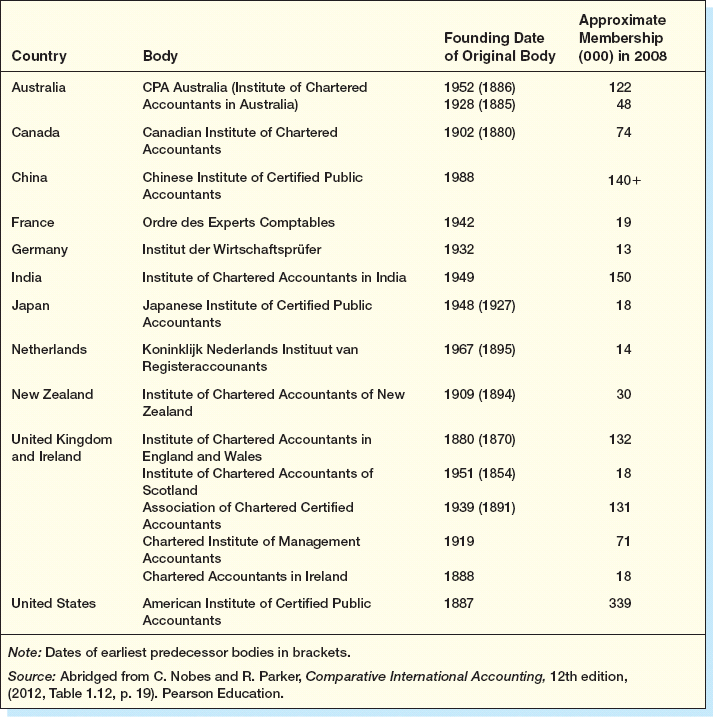

Figure 14.3 shows the age and size of some professional accountancy bodies. In the UK and the US, the accounting profession is very strong and influential. In the US, for example, in 2008 there were about 339,000 Certified Public Accountants (CPA). By contrast, in Germany, there were only 13,000 Wirtschaftsprüfer, the German equivalent of the CPA. In China and India, both countries with huge populations, there were only 140,000 and 150,000 qualified accountants respectively. In those countries with comparatively big accounting professions, such as Australia, the UK and the US, accountants have traditionally played an important role in developing national accounting. However, in France and Germany, professionally qualified accountants have far less influence on accounting. In these countries, traditionally there has been less flexibility in the accounting rules and regulations and less need for judgement. However, given the use of IFRS by listed companies this is gradually changing.

(vii) Spheres of Influence

Accounting is not immune from the wider forces of economics and politics. Many countries' accounting systems have been heavily influenced by other countries. The UK, for example, imported double-entry bookkeeping from Italy in the fifteenth century. It then exported this to countries such as Hong Kong, India, Kenya, Malaysia, Nigeria and Singapore. These countries still follow a model inherited from the UK. The UK also originally exported its accounting system to the US. However, from the early 1900s, the US has influenced the UK rather than vice versa. Overall, it is perhaps possible to identify three broad spheres of influence: the UK, the US and the continental European. Currently, the UK is being influenced by both the US and the more prescriptive continental European model. China was originally influenced by the centrally planned Russian system, but nowadays it is increasingly influenced by the West.

(viii) Culture

Culture is perhaps the most elusive of the divergent forces. Hofstede, in Culture's Consequences (Sage, 1980), defines culture as ‘the collective programming of the mind which distinguishes the members of one human group from another’. Building on the work of Hofstede, accounting researchers have sought to establish whether culture influences accounting. For example, do the French or the British have a collective culture which influences accounting? Using such concepts as professionalism, uniformity, conservatism and secrecy, they have found some, if not overwhelming, support.

Classification

Accounting researchers have sought to classify national accounting systems using, for example, divergent forces, cultural characteristics, and accounting measurement and disclosure practices. A useful classification system is described by Nobes (1983). Broadly, his system classifies countries as either having macro or micro accounting systems. Figure 14.4 uses the divergent forces to summarise the major national characteristics of macro and micro countries. It can thus be seen that macro countries, such as France and Germany, are typified by governmentally orientated systems where the influence of tax is strong, but that of the accounting profession is weak. Meanwhile, micro countries, such as the UK and the US, are typified by investor-orientated systems where tax influence is weak, but the influence of the accounting profession is strong.

Country Snapshots

Every country's accounting system and environment is a unique mixture of divergent forces. In this section, we look at the accounting systems and environments of five important developed and developing countries: France, Germany, China, the UK and the US. The aim is to provide a quick overview of the distinctive natural characteristics of each country's accounting systems.

France

The French accounting system is often cited as a good example of a standardised accounting system. It thus contrasts with the UK and US systems. Essentially, the French accounting system was introduced in order to provide the government with economic information for planning and controlling the French economy. The French system centres around Le Plan Comptable Générale (General Accounting Plan). This sets out a uniform system of accounting to be used throughout France. Of special interest is a chart of accounts where each item in the accounts is given a number. These numbers can then be used to aggregate items from different companies. Overall, Le Plan Comptable Générale resembles a comprehensive accounting manual which French companies follow.

In addition to Le Plan Comptable Générale, there are various detailed accounting and taxation laws. The role of taxation is particularly important. In essence, tax law drives accounting law. Standish (in Nobes and Parker, 2000, p. 205) states any company wanting to take advantage of various tax concessions needs to:

‘… enter the relevant tax assessable income or tax deductible charges in its accounts as if valid for tax purposes, even if the effect is to generate assets or liabilities that do not conform to the accounting criteria for asset and liability recognition and measurement.’

The accounting profession in France is much smaller than in the UK and US. There were 19,000 professional accountants in 2008 (Nobes and Parker, 2010, p. 206). Compared with other countries, the profession is not influential. There are, for example, no accounting standards in France comparable to those in the UK and US.

However, accounting in France has changed (see Soundbite 14.2) and is still changing rapidly. For many years, French companies have been permitted to use non-French accounting principles. Many large French groups, therefore, used US accounting principles or International Accounting Standards (IAS). Since 2005, French listed companies like all EU listed companies use IFRS in their group accounts. However, individual company accounts must still be prepared using French principles.

France

‘We're [France] somewhere between the United States and Germany on transparency, probably closer to US practices and certainly less able than German business to hide systematic abuses. We're going toward the US model, but it's going to take several years more.’

Alan Minc quoted in International Herald Tribune (October 10, 1996)

Source: The Wiley Book of Business Quotations (1998), p. 158.

Germany

Germany has traditionally had a relatively distinctive accounting system (see Real-World View 14.2). Essentially, it is very prescriptive, government controlled and creditor-orientated. Currently, there is no comprehensive body of accounting standards. The main regulations are contained in the Companies Acts, Commercial Code and Publication Law. These laws set out very detailed regulations.

German Accounting System

Traditionally, German accounting has followed a relatively distinct path. Germany, along with France, has always represented a continental accounting tradition based on a creditor rather than a shareholder approach. The Franco-German approach is in direct contrast to the Anglo-Saxon view of accounting. This latter view, typified by UK/US accounting, espouses an economic reality, user-based approach, with the main user being the shareholder.

Source: M.J. Jones, Germany: An Accounting System in Change, Accountancy (International edition), Vol. 124, No. 1272, August 1999, pp. 64–5. Copyright Wolters Kluwer, UK.

The measurement systems underpinning German accounting have traditionally been seen as very conservative. This is especially so when compared with UK accounting policies. For instance, in 1997 Rover, the UK car maker, would have made a profit of £147m under UK rules. Under German rules it reported a loss of £363m. Taxation law also dominates accounting; for example, expenses are only allowable for tax if they are deducted in the financial accounts of individual companies.

Germany

‘Accounting scandals are major drivers of the regulatory development. In response to accounting scandals, the legislative landscape in Germany has been changed fundamentally in the period between 1980 and 2006. For example, in 2005 the Financial Reporting Enforcement Panel, a new enforcement institution, was created responsible for the correctness of the financial statements.’

Source: Hansrudi Lenz (2010), Accounting Scandals in Germany, in Michael Jones, Creative Accounting, Fraud and International Accounting Scandals, p. 18. Reproduced by permission of John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

The German accounting profession is very small. In 2008, there were only 13,000 German professionally qualified accountants (Nobes and Parker, 2010, p. 20). There is, however, also a separate profession of tax specialists. Although small, the German profession is very well qualified. However, in Germany most accounting developments originate from the government rather than from the accounting profession.

By international standards, the German stock market is comparatively small. Its total market capitalisation is only about half that of the UK. German industry is financed principally by banks. The focus of German accounting, therefore, has traditionally been on assets rather than profit.

However, German accounting, like French accounting, has changed rapidly. Listed German companies, like listed French companies, use IFRS to prepare their group accounts. This internationalism of German accounting started in the 1990s. In 1990, no German companies were listed in the US. However, Daimler Benz caused a minor sensation in Germany by listing on the US exchange in 1993. Since then German companies have increasingly used US or International Accounting Standards. In Germany, in 2005, a German Financial Reporting Enforcement Panel was established to monitor the reporting standards of German companies.

China

China is modernising fast and its economy is growing rapidly. As a result it has recently become the World's second biggest economy overtaking Japan, but behind the US. China has had a long history of centralised government. This dictated its accounting system and up until the 1970s China's accounting was based on that of the Soviet Union. The Chinese economy was planned centrally and its accounting was a tool in that planned centralisation.

China

‘Since the introduction of economic reforms and “open door” policies in 1978, China has been in transition from a centrally planned to a market economy.’

Source: C.H. Chen, Y. Hu and J.Z. Xiao (2010), Corporate Accounting Scandals in China in Michael Jones, Creative Accounting, Fraud and International Accounting Scandals. Reproduced by permission of John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

However, from the 1970s the Chinese economy has modernised very fast mainly towards a socialist market economic system. By 2003, China achieved a 73% marketisation (Chen et al., 2010). Although ownership of the business enterprises remains substantially with the government, management and ownership are now separated making the concept of the business entity relevant (Nobes and Parker, 2010).

China's stock market has developed rapidly with nearly 2,000 listed firms (see www.scrc.gov.cn). The market capitalisation of Shanghai has now overtaken that of Hong Kong and by January 2009 China was approaching that of the UK in terms of domestic companies. However, the banking sector is still dominated by state-owned banks.

In terms of regulations, the government launched a major accounting reform in 1992. This resulted in several regulations including ‘Accounting Regulations for Share Enterprises and Accounting Standards for Business Enterprises’. The main users in China were considered to be the government, banks, the public and an enterprise's own management rather than investors (Nobes and Parker, 2010). In addition, ‘there is a high degree of conformity between tax and accounting figures, so that the calculation of taxable income is a major purpose of accounting’ (Nobes and Parker, 2010, p. 321).

In October 1998, an Accounting Standards Committee was founded. In 2000, a new uniform accounting system was introduced to replace the existing industry-based standards. Moreover, China was also issuing accounting standards (Xiao, Weetman and Sun, 2004). Then, in February 2006, a new set of Accounting Standards was developed for Business Enterprises (ASBEs). These are required for listed companies from 2007 and are very similar to IFRS (Nobes and Parker, 2010). The imposition of these new laws so quickly and the rapid modernisation of the economy has meant that enforcement has lagged behind. There have, therefore, been many scandals in China (Chen et al., 2010).

There has, however, been a rapid growth in the audit profession. The Chinese Institute of Certified Public Accountants (CICPA) was founded in 1988. It has grown rapidly and in 2008 had approximately 140,000 members (Nobes and Parker, 2010). Although very small in terms of its population (e.g., the UK has 132,000 members of the ICAEW alone), it does reflect an important and developing body of professionals.

Overall, therefore, Chinese accounting has, like its economy, been transformed over the last generation. This is perhaps unsurprising as accounting is often called the hand maiden of economics. In other words, it serves to support and develop the economic infrastructure.

The UK

The UK is still an important player in accounting worldwide. However, it is no longer the world leader. The current UK system contains elements of US and continental European accounting. The generally recognised objective of accounting in the UK is to give a ‘true and fair view’ of a company's financial activities to the users, most notably the shareholders. There are two sources of regulation: company law and accounting standards. Company law, which now includes the European Fourth and Seventh Directives, sets out an increasingly prescriptive accounting framework. The financial reporting standards, set by the Accounting Standards Board, provide guidance on particular accounting issues. They are followed by UK non-listed companies which constitute the vast bulk of UK companies. The UK has a Financial Reporting and Review Panel, which investigates companies suspected of non-compliance with the standards. The UK, therefore, has an unusual mix of regulations. UK listed companies now follow IFRS for their group accounts.

The UK's Accounting Standards Board is currently proposing a three-tier approach which would be effective from 1 July 2013. Under this, listed companies would continue to follow IFRS. Joining them would be other publicly accountable companies such as those trading debt on public markets or holding deposits.

In the second tier small and medium-sized companies would report under the ASB's proposed new accounting standard based on IFRS for SMEs (FRSME). This would be shorter and less complicated than current UK standards. A new standard ‘Financial Reporting Standards for medium-sized entities’ would be introduced. Finally, the smallest companies will continue to use a simplified version of UK standards, known as FRSSE.

The accounting profession in the UK is very influential and accounting in the UK is a relatively high status profession. It is also very fragmented, comprising the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW), the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Scotland, the Institute of Chartered Accountants in Ireland, the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants, the Chartered Institute of Management Accountants and the Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy. The ICAEW has traditionally been the largest body numbering 132,000 professionally qualified accountants in 2008 (see Figure 14.3). However, the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants is growing rapidly with a particularly strong overseas presence and in 2008 had 131,000 members.

Unique Features of UK Accounting System

Every country's accounting system and environment is unique. Can you think of three features of the UK's accounting and environment which contribute, in combination, to the uniqueness of the UK's accounting system?

There are many special features in the UK's system. Some of the main ones are listed below.

- Combination of a ‘true and fair view’ with Companies Acts, UK accounting standards and IFRS.

- The fragmentation of the accounting profession into six institutes.

- The dominance of the institutional investor in the stock market.

- The Financial Reporting Review Panel's role as guardian of good accounting practice.

- Non-listed companies are able to capitalise their goodwill and write it off to the income statement over 20 years (rebuttable presumption).

The main users of accounts in the UK are the shareholders. In particular, in the UK, institutional investors dominate. The stock market is very active and its market capitalisation is very high. Unlike most other countries, there is a separation between accounting profit and taxable profit. In essence, there are two distinct bodies of law. Certainly, taxable profit does not determine accounting profit.

The US

The US is one of the most important forces in world accounting. Most important developments in accounting originate in the US. A particular feature of the US environment is the position of the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC). The SEC was set up in the 1930s after the Wall Street crash of 1929. It is an independent regulatory institution with quasi-judicial powers. Listed US companies have to file a detailed annual form, called the 10-K, with the SEC. The SEC also supervises the operation of the US standard-setting body, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). This body has been designated by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) as the US's standard-setting body. At the time of writing this book, the FASB and the IASB are working on a project to converge US GAAP and IFRS.

FASB is the most active of the world's national standard-setting bodies. The members of FASB have to sever their prior business and professional links. FASB has published over 150 standards. It is supported by the Emerging Issues Task Force, which examines new and emerging accounting issues. The US accounting standard-setting model proved the blueprint for the current UK system. Unlike France, Germany and the UK, US listed companies follow their own national standards rather than IFRS.

US listed companies are thus well regulated. However, curiously for the mass of US companies, which are not listed, there may be very few accounting or auditing requirements. Company legislation is a state not a federal matter. Each state, therefore, sets its own laws.

The accounting profession in the US is both numerous and influential. There were 339,000 members of AICPA in 2008 (see Figure 14.3). Most of the world's leading audit firms have their head offices in the US.

The objective of accounting in the US is generally recognised as being to provide users with information for decision making. Most of the finance for US industry is provided by shareholders. Unlike in the UK, the majority of shareholders in the US are still private shareholders. The market capitalisation of the US stock market is the greatest in the world. Many of the world's largest companies such as Microsoft or the General Electric Company are US. The high-quality financial information produced by US financial reporting standards is often argued to help the efficiency of the US stock market. However, in 2001 and 2002 a series of high-profile accounting scandals involving companies such as Enron, WorldCom and Xerox led to a questioning of the quality of US accounting and auditing standards.

Real-World View 14.3 shows the connection between US capital markets and financial reporting standards.

US Financial Reporting

Financial Reporting and Capital Markets

There is a clear connection between the efficient and effective US capital markets and the high quality of US financial reporting standards. US reporting standards provide complete and transparent information to investors and creditors. The cost of capital is directly affected by the availability of credible and relevant information. The uncertainty associated with a lack of information creates an additional layer of cost that affects all companies not providing the information regardless of whether the information, if provided, would prove to be favorable or unfavorable to individual companies. More information always equates to less uncertainty, and it is clear that people pay more for better certainty.

Source: Edmund Jenkins, Global Reporting Standards, IASC Insight, June 1999, p. 11. Copyright © 2012 IFRS Foundation. All rights reserved. No permission granted to reproduce or distribute.

In the US, as the aim of the accounts is broadly to reflect economic reality, the tax and accounting systems are generally independent. There is, however, one curious exception: last-in first-out (LIFO) inventory (stock) valuation. Many US companies adopt LIFO in their taxation accounts as it lowers their taxable profit. However, if they do so, federal tax laws state they must also use LIFO in their financial accounts. However, since LIFO inventory values are generally old and out of date, this fails to reflect economic reality (see Chapter 16 for more on LIFO).

Convergent Forces

Convergent forces are pressures upon countries to depart from their current national standards and adopt more internationally based standards. Convergent forces thus oppose divergent forces. The advantage of national standards is that they may reflect a particular country's circumstances. Unfortunately, the disadvantage is that they impair comparability between countries and are a potential barrier to international trade and investment.

Pressures for Convergence

How might national accounting standards prove a barrier for a multinational company, such as Glaxo-Wellcome, or a large institutional investor, such as Aberdeen Asset Management?

The world of trade and investment is now global. Companies such as Glaxo-Wellcome will, therefore, trade all over the world and have subsidiaries in numerous countries. They will sometimes have to deal with accounting requirements in literally hundreds of countries. To do this takes time, effort and, more importantly, money. If there was one set of agreed international accounting standards, this would make the life of many multinationals easier and cheaper.

Large institutional investors will also be active in many countries. For them, there is a need to compare the financial statements of companies from different countries. For example, an institutional investor, such as Aberdeen Asset Management, may wish to achieve a balanced portfolio and invest funds in the motor car industry. It would wish to compare companies such as BMW in Germany, Fiat in Italy, General Motors in the US and Toyota in Japan. To do this effectively, there is a need for comparable information. A common set of international accounting standards would provide the comparable information.

There are three main potential sources for the convergence of accounting worldwide: the European Union (EU), the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) and the United States. The process of convergence through the EU is normally termed harmonisation, while that through the IASB is called standardisation.

European Union (EU)

The European Union is concerned with harmonising the economic and social policies of its member states. Accounting represents part of the economic harmonisation within Europe. In countries such as France and Germany, accounting regulation has always been seen as a subset of a more general legal regulation. Differences in accounting between member states are seen as a barrier to the harmonisation of trade.

The main legal directives affecting accounts are the Fourth Directive and the Seventh Directive. The Fourth Directive is particularly important to the UK. It is based on the German Company Law of 1965. The Fourth Directive ended up as a compromise between the traditional UK and the Franco-German approaches to accounting. The UK approach was premised on flexibility and individual judgement. By contrast, the continental approach set out a prescriptive and detailed legal framework. In the end, the Fourth Directive married the two approaches.

The UK for the first time accepted a standardised format for presenting company accounts and much more detailed legal regulation. However, France and Germany agreed to incorporate into law the British concept of the presentation of a true and fair view.

At one time, the European Union appeared to be developing its own standards. However, it has now thrown its weight behind IFRS. These are now required to be used by the more than 9,000 European listed companies for their group accounts.

Different Accounting Standards

‘Different accounting standards are a drag on progress in much the same way as diverse languages are an inconvenience. Unlike creating a world language, creating one set of standards is achievable. Apart from the potential savings for companies with diverse international structures, complying with an internationally understood accounting paradigm opens up a wider investment audience.’

Source: Clem Chambers, Talking the Same Language, Accountancy Age, 3 February 2005, p. 6.

International Accounting Standards Board (IASB)

The International Accounting Standards Committee (IASC) was founded in 1973 by Sir Henry Benson to work for the improvement and harmonisation of accounting standards worldwide. Originally, there were nine members: Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, Mexico, the Netherlands, the UK and Ireland, and the US. Member bodies were the national professional bodies of different countries. The IASC grew rapidly and, in 2001, 150 countries were members. The member bodies used their best endeavours to ensure that their countries followed International Accounting Standards (IAS). These were subsequently called International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). The IASC was reconstituted as the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) in 2001 (to simplify matters we generally use IASB for both IASC and IASB throughout this book).

At first, the IASB merely codified the world's standards. After this initial step, the IASB began to work towards the improvement of standards. The IASB set out a restricted number of options within an accounting standard from which companies could then choose. Up until the mid-1990s, it is fair to say that the IASB made only limited progress. A threefold differentiation in the IASB's impact was possible: lesser developed countries, European countries and capital market countries. Lesser developed countries, such as Malaysia, Nigeria and Singapore, adopted IFRS because doing so was cheaper than developing their own standards. In continental Europe, the IFRS were seen both as a problem and a solution. They were a problem in that generally IFRS were seen to adopt a primarily investor-orientated approach to accounting which conflicted with the traditional continental European tax-driven, creditor-based model. They were a solution in that IFRS were preferable to US standards. Increasingly, in the early 1990s, French and German companies adopted US standards. Karel Van Hulle, Head of the EU's Accounting Unit, commented in 1995, ‘It would be crazy for Europe to apply American standards, as it would be crazy for the Americans to apply European standards. We ought to develop those standards which we believe are the best for us or for our companies.’ Finally, for capital market countries, such as the UK and the US, the IFRS were generally already similar to the national standards. Even so, there was a great reluctance, particularly by the US, to accept IFRS.

A breakthrough agreement came in 1995. IOSCO (The International Organisation of Securities Commissions), the body which represents the world's stock exchanges, agreed that when the IASB had developed a set of core standards it would consider them for endorsement and would recommend them to national stock exchanges as an alternative to national standards. The advantage to IOSCO was that there would be a common currency of standards which could be used internationally. In particular, there was the hope that non-US companies could trade on the New York Stock Exchange without having to use US Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) or provide a reconciliation to US GAAP. The IASB subsequently experienced severe problems compiling a set of core standards. However, by 2000 these were in place. The importance of the IASB is shown in Real-World View 14.4.

Why IFRSs? Why Now?

The effective functioning of capital markets is essential to our economic well-being. In my view, a sound financial reporting infrastructure must be built on four pillars:

- accounting standards that are consistent, comprehensive, and based on clear principles to enable financial reports to reflect underlying economic reality;

- effective corporate governance practices, including a requirement for strong internal controls, that implement the accounting standards;

- auditing practices that give confidence to the outside world that an entity is faithfully reflecting its economic performance and financial position; and

- an enforcement or oversight mechanism that ensures that the principles as laid out by the accounting and auditing standards are followed.

As the world's capital markets integrate, the logic of a single set of accounting standards is evident. A single set of international standards will enhance comparability of financial information and should make the allocation of capital across borders more efficient. The development and acceptance of international standards should also reduce compliance costs for corporations and improve consistency in audit quality.

Sir David Tweedie, Chairman, International Accounting Standards Board Testimony before the Committee of Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs of the United States Senate, Washington, 9 September 2004

Source: Deloitte, IFRS in your pocket, 2005, p. 2.

At the start of the new Millennium, three developments substantially enhanced the power of the IASB. First, in 2000 IOSCO allowed its members to use IFRS standards. Second, the IASC was reconstituted as the IASB in 2001 with a new chairman, Sir David Tweedie. The four main elements were: the IASC Foundation, the IASB, the Standards Advisory Council and the Standing Interpretations Committee. The IASC Foundation appoints the IASB, raises money and acts in a supervisory role. The main objectives of the IFRS foundation (IFRS, 2010) are ‘to develop in the public interest, a single set of high-quality, understandable, enforceable and globally accepted financial reporting standards based upon clearly articulated principles’. To fulfil the required standards, financial statements and other reporting need to be of high-quality, complete and transparent for investors and other users of financial information in the world's capital markets to make the right economic decisions. From July 2011, there is a new head of the IASB, Hans Hoogervorst and as Real-World View 14.5 shows, the Board has a busy work programme up to 2016.

The IASB's Workload

One of the first tasks of the new board will be to set its work programme for the next five years. By the time it does this, several very significant projects (including revenue, leases, insurance contracts and financial assets and financial liabilities) should have been completed. China, Japan, India, Canada, Brazil and several other major jurisdictions should be well on their way to International Financial Reporting Standards adoption. The Securities and Exchange Commission should have decided whether US domestic issuers should be allowed or required to use IFRS in place of US GAAP. Ideally, all the standards issued by the old board should have proved acceptable to the EU and other jurisdictions that use IFRS and to G20 ministers.

Source: D. Cairns, Where next for the IASB? Accountancy Magazine, February 2011, pp. 30–1. Copyright Wolters Kluwer (UK) Ltd.

The IASB sets the IFRS. At the end of 2011, there were 14 members of the IASB board with each member having one vote. As at December 2010, there were eight IFRS and 29 International Accounting Standards (IAS) (i.e., developed by the IASC in existence). The Standards Advisory Council gives general advice and guidance to the IASB. The Standing Interpretations Committee interprets current IFRS, but also issues guidance on other accounting matters. There is also a Monitoring Board that provides a formal link between the trustees and public authorities and an advisory council which provides a forum for organisations and individuals to participate in the IASB's work. The third important development was the decision in June 2000 by the European Union that all EU listed companies would follow IFRS from 2005.

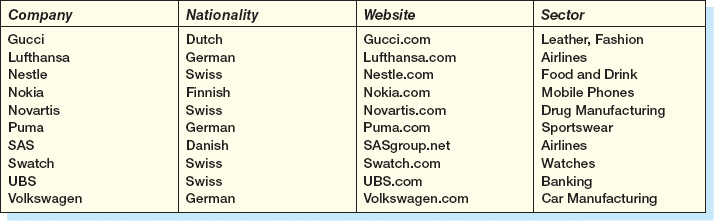

These three developments considerably enhanced the power of the IASB. By 2009, 110 countries required the use of IFRS for all listed companies and 80 countries required their use by unlisted companies. The web addresses of some of these companies as well as the IASB website are given in Figure 14.5.

Figure 14.5 Some Useful Web Addresses for Companies using International Financial Reporting Standards

The IFRS are continually being revised. The standards in existence in 2010 are listed as an Appendix to this chapter. There are, in addition, many interpretations (guidance documents) as well as the IASB's The Conceptual Framework which is in the process of being updated. This framework defines the objectives of financial statements, the qualitative characteristics of financial statements and the basic elements and concepts of financial statements. IFRS, like all standards, are ultimately political in nature; as Real-World View 14.6 shows, there has been much concern about the global rules on fair value accounting. Many critics have blamed fair value for the global financial crisis.

A Pyrrhic Victory?

‘IFRS is a good idea in principle, but the problem is the politics and whether the US gives up its sovereignty,’ says Roger Barker, head of corporate governance at the Institute of Directors. And if too many global accounting rules are watered down in order to secure US support, IFRS will be a ‘pyrrhic victory’, Barker adds.

Jonathan Russell, a partner at Russell Phillips and Rees Russell and a former president of the UK 200 Group of chartered accountants and lawyers, says: ‘For most small businesses, this is something that isn't even on their radar, so if and when the global accounting rules become compulsory, it will just be something else they expect their accountants to deal with.

At present at my firm I have about two clients who use international standards, which creates extra difficulties for us because we have to be familiar with UK and international GAAP.’

Big Four accounting firms appear more enthusiastic about IFRS, Pauline Wallace, UK head of public policy for PricewaterhouseCoopers, and an expert on IFRS, says that momentum towards global accounting standards appears unstoppable, and is not reliant on US support.

‘The IASB has done a phenomenal job in getting its standards applied across the world,’ she says. ‘There is a real groundswell towards IFRS. If the US doesn't give its support for IFRS, it will be unfortunate, but it won't be a killer blow.’

Source: N. Huber, Rule the World, Accountancy Magazine, May 2010, p. 26. Copyright Wolters Kluwer (UK) Ltd.

A consistent problem for the IASB has been the attitude of the US. Traditionally, the US has been reluctant to adopt IFRS. Although, in principle, the US favours world standards, it has several concerns about IFRS. It feels they are not as rigorous as US standards and is also worried about their enforcement. However, the shortcomings of US accounting standards revealed by recent US accounting scandals have made the IAS potentially more attractive to US regulators. In October 2003, a joint convergence project was begun by the IASB and the FASB. The aim of this project is to eliminate differences between the standards set by the IASB and FASB. Short-term convergence projects were set to be completed by 2008 with a decision by the US on convergence to follow and no decision had been made when this book went to press in March 2013. However, even if the US does replace US GAAP with IFRS this is unlikely to be before 2015.

US Acceptance of IAS Standards

Cynics argue that it is in the US's interests deliberately to delay accepting International Accounting Standards. Why do you think this might be?

US standards are probably the most advanced of any country in the world. The US is also the richest country in the world and a source of potential capital for companies from other countries. To gain access to US finance, many overseas companies list on the US Stock Exchange. However, to do this they must adopt US standards or provide reconciliations to US standards. As time passes, more foreign companies adopt US standards. Cynics, therefore, believe that the US may be playing a waiting game. The longer the US delays approving IAS, the more foreign companies will list on the US exchange. These cynics argue, therefore, that it is in the US's interests to delay accepting IAS.

From a UK perspective, the Accounting Standards Board, which sets standards for UK domestic non-listed companies, has accepted, in principle, the need for eventual international harmonisation. The current policy is to depart from an international consensus only when there are particular legal or tax difficulties or when the UK believes the international approach is wrong. Recently, the ASB has made important efforts to harmonise UK and IAS standards in key areas such as goodwill, taxation and pensions. The UK is also harmonising its accounting practices with those currently used in the US. The ASB has also agreed, in principle, that IFRS should be used for all publicly accountable entities.

US Standards

There is still the possibility that if the SEC refuses to endorse the IFRS, US standards will become a substitute for worldwide accounting standards. More and more companies worldwide are being listed in the US. The advantage of using US standards is that this enables non-US companies to list on the New York Stock Exchange. This is the world's largest stock exchange and a ready source of capital. Currently, these companies have to reconcile their earnings and net assets to US GAAP if they use IFRS or their own national standards.

Conclusion

Different countries have different accounting environments. These accounting environments are determined by divergent forces, such as objectives, users, sources of finance, regulation, taxation, the accounting profession, spheres of influence and culture. These divergent forces are interrelated and the mix of divergent forces is unique for each country. Countries can be classified as having macro or micro accounting systems. In macro countries, such as France or Germany, the emphasis is on tight legal regulation, with a creditor orientation and a weak accounting profession. By contrast, in micro countries such as the UK and the US, there is a focus on regulation via standards rather than the law and an overall investor-orientated approach with a strong accounting profession.

The great variety of accounting systems worldwide impedes the growth in world trade. Consequently, there are pressures for countries to depart from purely nationally based accounting. The pressures result from the growth in multinational companies and in cross-border trade and investment. These convergent forces thus counteract the divergent forces.

At the European level, the European Union works towards the harmonisation of accounting practices. On the global level, the International Accounting Standards Board sets International Financial Reporting Standards. Having made a slow start, the IASB is now gathering momentum.

There is now an agreement by the International Organisation of Securities Commission that its members are allowed to use IFRS when listing on individual exchanges. However, the US Securities and Exchange Commission still has reservations. In Europe listed companies must now use IFRS.

Selected Reading

1. Books

International Accounting is blessed with some very good, comprehensive books. As International Accounting is continually changing, it is always necessary to check that you have the latest edition.

Chen, C.H., Hu, Y., and Xiao, J.Z. (2010) Corporate Accounting Scandals in China, in Jones, M.J., Creative Accounting, Fraud and International Accounting Scandals.

Nobes, C.W., and R.H. Parker (2010) Comparative International Accounting (11th edition), (Pearson Education Limited: London).

This is the longest standing of the books. Nobes and Parker write some of the chapters themselves, but there are also useful chapters by other authors, especially Klaus Langer on Germany.

Roberts, C., Weetman, P. and Gordon, P. (2002) International Financial Accounting: A Comparative Approach (Financial Times Management: London).

This book provides a comprehensive coverage of the issues in this chapter.

Walton, P., Haller, A. and Raffournier, B. (1998) International Accounting (International Thompson Business Press: London).

Once more this is a useful book. Each chapter is written by a specialist.

2. Articles

Students may find the following three articles provide a reasonable coverage of the International Accounting Standards Board and Germany, respectively.

Jones, M.J. (1998) ‘The IASB: Twenty-five years old this year’, Management Accounting, May, pp. 30–32.

Jones, M.J. (1999) ‘Germany: An accounting system in change’, Accountancy International, August, pp. 64–65.

Nobes, C.W. (1997) ‘German Accountancy Explained’, Financial Times Business Information, London.

The key article on the micro–macro classification of accounting systems is listed below. Also there is a useful chapter in Nobes and Parker (2004).

Nobes, C.W. (1983) ‘A Judgmental International Classification of Financial Reporting Practices’, Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, Spring, pp. 1–19.

Xiao, Z., Weetman, P. and Sun, M.L. (2004) Political Influence and Co-existence of a Uniform Accounting System and Accounting Standards in China, Abacus, Vol. 40, No. 2, pp. 193–218.

Provides an overview of regulatory change in China.

Discussion Questions

Discussion Questions

Questions with numbers in blue have answers at the back of the book.

| Q1 | Why is the study of international accounting important? |

| Q2 | What are the main divergent forces and which are the most important? |

| Q3 | Compare and contrast the main features of the Anglo-American and continental European accounting systems. |

| Q4 | Taking any one country, rank the divergent forces in order of importance. |

| Q5 | Has the UK more in common with the US than with France? |

| Q6 | Will the convergent forces outweigh the divergent forces? |

Appendix 14.1: List of International Standards

IFRS as in Existence as at December 2010

International Accounting Standards (IASs)

As in existence at December 2010.

Go online to discover the extra features for this chapter at www.wiley.com/college/jones

Go online to discover the extra features for this chapter at www.wiley.com/college/jones

SOUNDBITE 14.1

SOUNDBITE 14.1 REAL-WORLD VIEW 14.1

REAL-WORLD VIEW 14.1

PAUSE FOR THOUGHT 14.1

PAUSE FOR THOUGHT 14.1