SECTION 6

Delivering: Final Presentation Preparation

After you've developed your data‐driven presentation content, you must prepare for and practice your delivery. Knowing what you'll say, anticipating the questions you'll receive, and validating that your spoken words flow smoothly are critical to success. Without proper preparation, you risk having all of your previous work be for naught. Here are some of the concepts discussed in this section:

- Consult a confidant and/or sponsor.

- Adapt your presentation to the audience.

- Be prepared to cut your presentation substantively short.

- Have multiple backup plans for handling problems that can arise.

- Ensure your key points are clear and that you draw attention to the right places.

Your final preparation is the last chance to ensure your messaging is on target, your slides are easy to follow, and that you're able to successfully drive home the points that you want to make. During final preparations, you'll always find some fine‐tuning that will make your presentation better as well as spots where you need to make your verbiage clearer and crisper. Most important, you can identify where your content is strongest (and weakest) and adjust your presentation flow for maximum effect.

Tip 83: Practice Your Presentation

You won't know how long your presentation will take without practice runs. Next time you have a presentation ready but have not yet delivered it, make an estimate of how long it will be. You'll almost certainly be off, and often by a sizable percentage. You can get away with finishing a presentation faster than estimated, but if you're slower than estimated, you'll run short of time and will either not complete your presentation or will have to move too quickly to finish it properly.

In addition to validating your timing, forcing yourself to go through your presentation will enable you to tune your flow by identifying where you are smooth, where you struggle, what content seems stronger and weaker than you expected, and where you might have too much redundancy or technical detail. I have had many occasions where I thought my flow was solid, but during a dry run I realized that it needed some changes. I also routinely find places where I struggle for the words to get my point across. I then focus time on tuning those sections of my narrative.

Some people resist the idea of a practice presentation because it can seem silly to be in a room by yourself presenting. However, think about written documents. Does anyone you know send out a written document that is the first draft with no further review? No way. Everyone understands that multiple passes of edits are required to get a document to the level it needs to be. Why would a live presentation be any different? You may be speaking instead of writing, but it is still about getting the right words in the right order to deliver your message clearly and concisely. Many people will make multiple rounds of edits to their slides, but somehow don't think to also do multiple passes of what they will say to support those slides. If presenting by yourself is too uncomfortable, invite a friend or two to sit in and offer feedback (see Tip 84).

If you have presented material multiple times and are comfortable with it, you may not need to do a full practice run because your prior presentations serve that purpose. You might still do a quick pass as a refresher, however. In my work, I have developed literally thousands of slides on different topics. I keep a log of approximately how long each one takes, and that enables me to estimate the length of a new combination of slides fairly accurately even without a practice run. However, if I haven't used certain slides in a while, I'll still do a practice run of them to refresh myself with how to speak to each slide. I also always time out new slides as soon as I create them.

If you aren't yet used to speaking to a live audience, you can hone your skills further by making a video of a practice run. Ideally, you should video yourself in the environment in which you'll be presenting, whether in a conference room, on a stage, or over a virtual platform. Watch your video and you'll see all sorts of things you'll wish you hadn't. You may find you're speaking too softly (it is almost impossible to speak too loudly in most presentation environments), or that you're speaking too quickly, or that you're looking at your notes too much, or that you keep scratching your head. Seeing and hearing yourself as the audience does is a great way to spot ways to improve your presentation mechanics.

Tip 84: Consult Some Confidants

No matter how diligent you are when putting together your data‐driven presentation, you will always miss something. You may have blind spots that are causing you to neglect making a key connection between findings. You may have developed a flow that is distracting you from optimally communicating your message. One of your points might be of no practical interest to your audience, though you aren't aware of that fact.

One great way to identify such issues is to consult with one or more confidants as you make final preparations for your presentation. By providing a preview to friendly outsiders, you get the honest feedback you need to help flag the areas of the presentation that need more work. Especially for a high‐stakes presentation, it is incredibly risky for you to go into the room having never gone through the presentation for anyone but yourself or your core project team. There are two types of confidants to consider pulling into the process.

First is someone from your extended team who is totally familiar with the type of project you executed and the methodologies that you made use of, but who is not familiar with the specifics of your project. Such a confidant can catch technical inconsistencies or gaps by bringing fresh eyes and expertise to the table.

Second is someone from the project's sponsoring organization, whether an internal business unit or an external company. This is someone you trust, but who does not have expertise related to your project. Such a confidant will help identify areas that are confusing or unclear to a nonexpert audience. Most important, they can validate that the way you are positioning the findings and recommendations will, in fact, resonate with the audience for which it is intended.

In the consulting world, we always look for an inside coach at a client who is friendly to our cause and who is willing to help ensure that we hit the mark so that we can provide the most benefit to the coach's organization. It is impossible to overstate how important candid feedback from someone who intimately understands your audience is. An inside coach will know things that you don't know about the audience and project politics and will be able to help you tighten up your narrative and approach.

Of course, consulting confidants will take time. Even more time will be required to make the adjustments that are suggested by the confidants. You can't leave it to the last minute. Per Tip 10, you must place time in your budget up‐front or you risk not having time to consult with your confidants as your presentation nears. Prevent that from happening!

Tip 85: Don't Overprepare

It sounds odd to say that it is possible to overprepare for a data‐driven presentation, but it is. We just discussed in Tips 83 and 84 how critical it is to prepare. We'll discuss in Tip 101 how damaging it can be to read your slides. Only a single step up from reading slides is when your presentation is so rehearsed and so well memorized that it makes you sound dull and monotone. Preparation is critical, but it really is possible to overdo it.

You certainly want to spend time rehearsing what you'll say, but only take rehearsing so far. I create a few bullets for myself related to each slide. These bullets will remind me of the main points I need to make on that slide. Instead of scripting my narrative verbatim, I purposely keep it to a couple bullet points. Of course, to discuss those bullet points will require many more words. By not scripting my words for each point, I am forced to verbalize my points on the fly in terms of the specific phrasing I use to make each point. Although every iteration of my presentation will be slightly different, it will sound more natural, authentic, and conversational to the audience.

Even with bullets, you can rehearse so much that you're still reciting more than speaking. Find the sweet spot where you know your material well enough that you generally know what to say for each slide. Then, stop there and trust that when the time comes, you'll say something consistent enough to succeed.

If you are so uncomfortable without a script that you feel that you absolutely must use one, then the lesser evil is to use the script. This is preferable to stumbling or losing your place repeatedly if you are not able to explain your points on the fly. But make it a goal to get better at going without a script. Pay attention to speakers at meetings you attend, and I promise that you will easily tell who is reading a script and who is just talking. It is very easy to tell the difference even if you close your eyes so you can't see the person looking at their notes. You can absolutely hear the difference. Hearing that difference will motivate you to avoid fully scripting your presentations.

Tip 86: Adjust Your Story to the Audience

You've just pulled together a crisp, focused presentation and story for your meeting with the marketing team when you are asked to present to the finance team next week. The good news is that you can take your presentation and story to the next meeting as is, right? Wrong! The marketing team will be interested in how they can leverage your findings to improve their message, targeting, segmentation, and so on. However, the finance team will want to know what this will mean to investment ROI and future revenues. Unfortunately, the right presentation for one audience might not be the right presentation for another. Per Tip 5, you must know each audience and adjust your delivery accordingly.

My friend Brent Dykes gave a great example of this concept in his book Effective Data Storytelling (Wiley, 2020). I will provide my own version of his example here. Consider the classic tale Little Red Riding Hood. Many movie versions have been made of this story. Regardless of the viewing audience, would you just grab any one of them to show at an event? I think not! Figure 86a shows just a few of the different versions that have very disparate approaches.

If you put Little Dead Rotting Hood up at your child's birthday party, you'd probably lose all of your future playdates! At a child's party, you'd better go with Hoodwinked. However, if you put Little Dead Rotting Hood up at a college party on Halloween night, it could be a big hit. The important thing is that different audiences want to hear the story in different ways. Regardless of which movie version you play, the audience will come away with the basic premise of the story even as the specifics of the delivery of the basic premise vary widely. What will succeed with one audience may fail miserably with another.

FIGURE 86A Same Story, Very Different Target Audiences!

It is no different when presenting data‐driven content. A marketing team is going to care most about how a recommended action will lift marketing results and how it will be perceived by customers. A finance team is going to care most about the costs and ROI. The legal team is going to care most about ensuring that the company isn't exposed to legal risk. In the end, your overall story points and recommendations are the same for each audience. However, you will need to emphasize and order things differently to succeed with each group.

Gloss over the legal considerations with the marketing team and then drill into the projected lift. With the finance team, gloss over the lift, but then focus on the costs and ROI. Each audience will hear the full story, but they'll also have their specific preferences and viewpoints addressed in the delivery. Often, you can leave the presentation slides themselves mostly untouched while adjusting your verbal commentary and how long you focus on each slide. However, it is an absolute must to adjust your delivery for each audience.

In a situation with a broad and diverse audience, attempt to give everyone's needs a little bit of focus while acknowledging to the audience that additional conversations may be required for different stakeholders to drill into more of the details they care most about. People will understand that you can't be as precise in your targeting with a broad group. However, give a little more emphasis to the points most relevant to whichever audience member(s) you most need to influence.

Tip 87: Focus on Time, Not Slide Counts

One thing that drives me crazy is when people worry about how many slides you should have for a given time allotment. Not only is this not the right way to organize a presentation but also everyone has different opinions on the right number of “minutes per slide.” I've heard one minute, two minutes, and even five minutes per slide used as a rule of thumb. Which is correct? Any of them can be … depending on the content.

Every slide is different. I have some slides that I talk through in 30 seconds or less. I have other slides that I talk through for 10 minutes or more. An audience won't notice how many slides you cover if they blend into the background of the flow of a compelling story and you finish on time.

The slide in Figure 87a can be covered very quickly. The slide in Figure 87b is the type of slide that might require minutes of discussion about each stage in the cycle as well as how they fit together.

When you add animations into the mix (see Tip 23), slide timing gets even murkier. Animations can turn a single slide into effectively many slides. I have seen people (including myself!) meet arbitrary slide limits by using complex animations to combine multiple slides into one.

Focus on creating a presentation that gets your points across succinctly, clearly, and with as few slides as possible. However, the slide count doesn't matter. What matters is that you complete your presentation in the time allotted while meeting the presentation's objectives. If your dry run (see Tip 83) shows you within the time limit, do not stress over having “too many” or “too few” slides. Just hit your time!

FIGURE 87A A Slide That Can Be Covered Quickly

FIGURE 87B A Slide That Might Take a While to Cover

Tip 88: Always Be Prepared for a Short Presentation

Tip 8 probably made you hope that you are asked for a long presentation next time. If so, I have bad news. Even if you are asked for a long presentation, you must also be ready for a short presentation. “How can that be?!?!,” you ask.

Even when there is no official question‐and‐answer slot, you can be sure that someone will ask questions. Next, you will almost always lose time as people come to the room and get settled. Between a few stragglers, some introductions, and a little small talk, you just lost more time. You may also be but one part of a broader agenda. When early speakers run long, those later in the agenda get squeezed on time. But none of these are the biggest time killers.

The higher up the chain your audience, the more likely that they will come late and/or leave early and/or be pulled out of the meeting temporarily in the middle. All of these will take from your time. In my career, I have had many occasions where an hour meeting turned into 15 or 20 minutes at the last minute. I once had a meeting with a chief marketing officer that went from a dedicated hour to 5 minutes walking together in the hall. Good thing I had my “elevator pitch” version ready!

All of that implies that if you aren't ready to make all of your key points quickly if necessary, you won't get to finish your story and you'll leave the audience hanging. It is very hard to be persuasive when you don't make all your arguments and don't get to your conclusions.

Always plan ahead by identifying what you would cut out first, second, and so on if you get crunched for time. That makes it easier to adjust at showtime. I think some of my best presentations have been those where I had to compress my content well below what I was comfortable with at the last minute. By preparing in advance to cut down the content, I was ready to do it, and the compressed time forced me to be highly focused and efficient with my delivery. Focused and efficient delivery is what audiences want regardless of the time you have. If you can pull off your presentation even when the audience knows they substantively cut your time, you'll score big points.

Tip 98 will discuss why you should always have multiple backup plans in case there are issues with technology. One of these backups is a printed version of your slides. I really like the PowerPoint feature that allows you to print four, six, or nine slides on a single page. This format lets you see what's coming next with just enough detail to remind you what you need to say. See Figure 88a.

FIGURE 88A PowerPoint Printout of Multiple Slides

FIGURE 88B Mark Off Points to Skip

On that printout, mark which slides you'll skip if pressed for time and in what priority. If you lose time up‐front, you can quickly hide the slides you need to skip. If you're delayed while presenting, just skip past the slides. I have had many occasions where I was looking down at my slide overviews at the front of the room and thinking, “That one has to go now. Uh oh, another question, I'll skip this one, too.” I will mark out each slide with a pen as in Figure 88b. This trick has helped me keep my cool under pressure.

Tip 89: The Audience Won't Know What You Left Out

Something that causes many presenters angst is the content that they are forced to skip when pressed for time, as in Tip 88. You will know everything you did cover along with everything you didn't cover. It is important to remember, however, that the audience will know only what you cover and will have no knowledge of the additional material not shared. If your presentation is effective in getting the audience to agree to take action, they will be happy while being oblivious to what they missed.

This is a hard tip to follow in practice. I routinely must remind myself not to worry about the point(s) I had to skip. In my mind, of course, I stress over how the extra point(s) would add value and make the presentation better. I then force myself to take the audience's perspective. Unless the content I skipped contains critical pieces of information that would fundamentally change the audience's opinion of, and willingness to act on, my presentation, then the missed content has a negligible impact.

This tip can come into play as you prepare and not just when you are forced to shorten your presentation at the last minute. Often, I'll have a range of points I think are worthy of mention. Once I lay them all out, it becomes clear that I have more material than I can cover in the time that I have been allotted. In that situation, I must cut points during my preparation. As I struggle to decide what to cut, I focus on identifying the points that are either the least impactful or most redundant to other parts of my story. I can usually find a way to cut points so that I am still happy with my presentation and the reception I think it will receive. I accept the need to cut, I make the cuts, and I move on.

I moderate a lot of conference panels, and this tip also comes into play during those sessions. I always have a set of questions that I plan to ask the panelists. Inevitably, between people talking longer than expected and audience questions, I can't get to all the questions. Although I may be disappointed that I didn't get to ask a couple of my questions, I remind myself that the audience never knew the questions existed. If a panel runs smoothly, who cares about questions not asked?

To illustrate how this tip works in the context of this book, can you name one or two topics that were originally planned for the book but ended up being cut? Of course not!

Tip 90: Scale Figures to Be Relatable

The scale used to discuss findings can affect how easily the audience is able to comprehend the results. Nontechnical audiences have trouble processing small fractions or very large numbers. For example, nonprofits often make claims such as “For every semester we provide our free tutoring services to a student, their test scores rise by 10 points!” This approach is a great way to make impacts very tangible and relatable.

You must determine what scale will best enable the audience to appreciate your results. Consider the statement “For every dollar we invest in free tutoring, test scores rise by 0.01 points.” Given that a dollar is a small amount of money, the impact of each dollar should be small. As a result, the claim doesn't sound remotely impressive. The fix? Change the scale! Instead say, “For every $1,000 invested in our free tutoring, test scores rise by 10 points.” While maintaining the exact same mathematical relationship, it sounds much more impressive. It is also a fair scale to use because $1,000 is about what a semester of tutoring costs.

Similarly, analytical results are often put in context of odds. “For every shot of vodka consumed in a year, the chance of a drunken injury goes up by 0.1%” doesn't sound so bad. “For every gallon of vodka consumed over a year, the chance of a drunken injury goes up by 10%” sounds more concerning. Once again, the scale chosen affects how relatable the information is and how it is perceived.

Figure 90a makes a meaningful point with a bad choice of scale. It sounds meaningless. Figure 90b adjusts the scale and gets your attention.

FIGURE 90A This Scale Is Hard to Relate To

FIGURE 90B This Scale Is Very Easy to Relate To

Tip 91: Be Clear about the Implications of Your Results

Although you must focus on keeping your data‐driven presentation as simple as possible, chances are that it may still be more complex and difficult to follow than your audience is used to. One way to help is to be very clear on exactly what you are (and are not!) saying about the implications of your work. Explain the bounds, ask if there are questions, and generally be attentive to how well the audience is understanding your results.

One common way to cause a lot of confusion, especially for a nontechnical audience, is to leave ambiguity in their minds as to exactly what you are saying. You need to be very precise not only in defining your terms (as per Tips 31, 33, 56, 57) but also in specifying where your findings apply and where they don't. You don't want the audience mistakenly deciding to apply your findings in a way that they shouldn't apply them.

Consider an example where a machine learning model predicts which customers will be late paying their bill. That model specifically says only whether a given customer will be late or not. It doesn't say anything about how late customers might be. A second model can be built to predict how late a customer will be, given that they were predicted to be late by the first model. Both of those models sound very similar to untrained ears, and it would be very easy for the audience to get confused as to which model you are discussing at any point during your presentation. You need to define both models precisely and then be clear about which model you are discussing at each point in time during your talk.

One way to validate that you have spoken precisely enough is to ask an audience member a question about how to apply what you have presented. If they struggle to answer and are clearly confused about how to answer, then you need to recap how to apply your results again to help the audience along. Your practice run with a confidant (see Tip 84) is also a great time to check this.

As you prepare your slides and your story, think about how you'll precisely explain each piece of data and each implication from the start. The more you plan and practice to ensure that what you present will be precise and clear (see Tip 83), the more likely you are to have your presentation viewed that way by your audience.

Tip 92: Call Out Any Ethical Concerns

Due to data breaches, faked research results, invasive use of personal data, and more, people across the globe have become much more sensitive to ethics and privacy. You are taking a big risk if you don't proactively think through potential ethical concerns related to any scientific or analytical work you undertake. You then have a responsibility to inform your audience of any concerns.

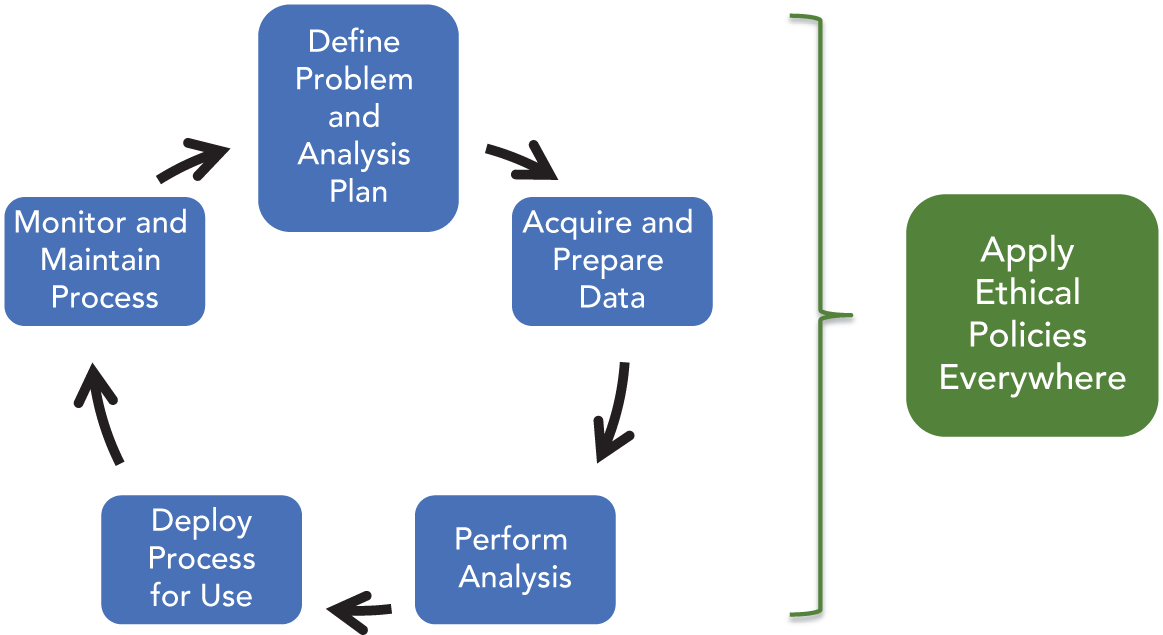

In my world of analytics and data science, the need for consideration of ethics permeates all stages of the conception, creation, and deployment of a new analytical process. Figure 92a shows a generic, yet typical, process. How do ethical considerations enter every phase?

- Define problem and analysis plan.

- Is what you are trying to do ethical? For example, predicting which employees will experience mental illness with the intent to fire them is not.

- Acquire and prepare data.

- Is it ethical to use the data you plan to use for the purpose you plan to use it? For example, should medical records be linked with credit records?

- Perform analysis.

- Are the completed models biased against certain groups?

- Deploy process for use.

- Are there controls to ensure the model is only used as intended?

- Monitor and maintain process.

- Are there protocols to ensure the model works as intended?

There are so many ethical considerations that I released a book titled 97 Things about Ethics Everyone in Data Science Should Know (O'Reilly Media, 2020) focused solely on the subject. At a minimum, commit to being intentional about considering ethics in any of the technical work that you do. Calling out ethical concerns isn't just the right thing to do, but it is increasingly necessary to protect your reputation and that of your organization.

FIGURE 92A Where Does Ethics Need Consideration?

Tip 93: Use Simplified Illustrations

We've discussed in many tips the need to keep your slide content short, easy to understand, and visual. This can take the form of greatly simplified conceptual illustrations to get important data across conceptually, without burdening the audience with unneeded and complex details. Your final preparations are a great time to identify places where you can simplify your graphics further.

Machine learning models produce parameters that express how much one factor predicts another. For example, how much does income level predict fine wine consumption? A formal written report will certainly need to contain details about the parameter values, model diagnostics, and more. However, do you really need to show your live audience all that detail? No! Comparing complicated numbers in their heads isn't something you want the audience doing when they are supposed to be listening to you.

In the case of relative measures such as parameter estimates, one option is to focus on the direction and relative magnitude/importance of each parameter with a graphical icon, such as an arrow or a speedometer, instead of a raw number. This enables the audience to quickly see what's positive and what's negative. If they are really interested in the parameter values, they can ask and you can jump to the appendix that has the numbers. (Of course you will have this in an appendix per Tip 19, won't you?) This approach streamlines your discussion and increases audience comprehension.

Figure 93a shows a table of parameters as values, which is the typical approach. A nontechnical audience may not be sure what to do with these. Figure 93b uses arrows to express the information more visually. It enables the audience to grasp the core information, but with limited mental effort.

FIGURE 93A Typical Approach with Exact Figures

FIGURE 93B Simplified Approach Emphasizing General Direction

Tip 94: Don't Include Low‐Value Information

This is another tip that should be really obvious, but apparently it isn't to a lot of presenters because this error occurs frequently! Few would question that including low‐value information is pointless, so don't be the person who includes it. However, “valuable” depends on context and perspective. As you finalize preparations, keep an eye out for places where information you've included isn't as valuable as you hoped when you compiled it.

Consider an experiment testing if some sensor brands have more defects than others. From a technical perspective, it may seem worthwhile to include detailed data showing a negligible difference in defect rates across multiple sensors. Figure 94a shows a table with nearly identical data that adds little value and will distract the audience from your story. Don't make the audience look at a table with 10 nearly identical numbers to validate for themselves that they are almost identical.

From a typical audience's perspective, they have no interest in seeing such data while you present. They would prefer to take your word for it if you just stated that there was no difference and moved on. If the data shows that every brand has within rounding error of the same defect rate, then call out that fact and display the rate that the sensors cluster tightly around. Figure 94b calls out that the numbers were similar and shows the average, minimum, and maximum. There are many fewer numbers to interpret, and the point can be seen immediately. Of course, you can have the detailed data ready in an appendix in case someone did care.

Valuable differences aren't always large differences, however. Sometimes even very small differences matter. This tip is about value in terms of importance, not magnitude.

FIGURE 94A There Is Little Value in Seeing All the Specific Defect Rates

FIGURE 94B A More Focused Way to Make the Point

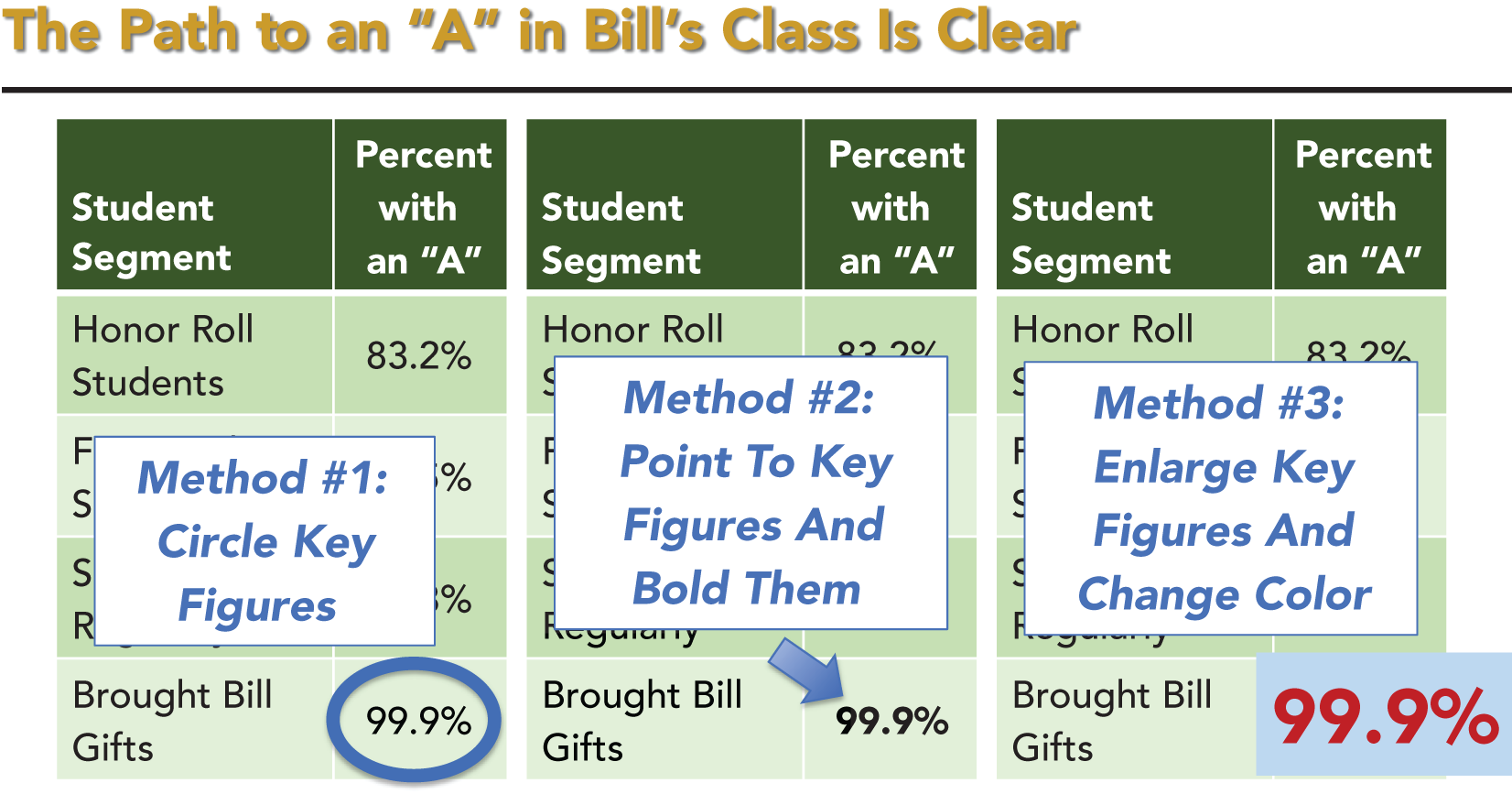

Tip 95: Make Critical Numbers Stand Out

Some pieces of information are far more important to the audience than others. As you finalize your preparations, make the most important pieces of information very easy for the audience to focus on. In Tip 23, we discussed highlighting information using animations to control the flow of information. In this tip, we address it from the perspective of drawing your audience's attention to important information. When making your final preparations, as you identify numbers that are especially critical, make them stand out.

There are multiple ways to highlight numbers in a table or chart. You can circle them, draw an arrow pointing to them, make them a different color, make them a different font size, bold them, or any combination of those techniques. You can do this with or without the animations discussed in Tip 23. The goal is to make it very easy for the audience to see the most critical pieces of information you will be discussing.

Don't underestimate the power and impact of this technique. When tables and charts are displayed, everyone in the audience will immediately attempt to interpret what they see and determine what is important. This takes mental energy, takes their attention from you, and risks them focusing on something you didn't intend.

When critical pieces of information are highlighted, people's attention will go straight there because they will assume that is where their attention should be. Combined with your narrative discussing the same information, it will keep the audience on track for hearing and comprehending your message. Figure 95a shows a basic table with nothing highlighted. Figure 95b demonstrates several different ways that the critical number can be highlighted for the audience.

FIGURE 95A It Isn't Clear where the Audience Should Focus

FIGURE 95B Options to Draw Attention to the Main Point

Tip 96: Make Important Text Stand Out Too

Tip 95 discussed drawing audience attention to critical numbers within tables or graphs. Another good practice is to draw audience attention to important text on your slides. As with highlighting numbers, highlighting text helps focus the audience on the most important parts of your content, which will often be some statement of impact, value, or risk. As you make your final preparations, look for opportunities to focus your audience on the critical text.

There are many ways to highlight important text. You can bold the text, make it a different color, italicize it, underline it, or any combination of those techniques. Regardless of the technique, the goal is to make it easy for the audience to identify the most critical pieces of information that you will be discussing. By now, you know to keep text to a minimum and so you'll be highlighting just a couple words out of a short sentence.

As discussed in Tip 95, don't neglect to use this technique. When text is shown on the screen, the audience will immediately read the text. When critical pieces of information are highlighted, people's attention will go straight there because they will assume that is where their attention should be. This is true for text as well as figures. Combined with your narrative discussing the same information, it will keep the audience on track for both hearing and comprehending your message.

Figure 96a shows an executive summary with nothing highlighted. Figure 96b demonstrates several different techniques to highlight critical text for the audience. Of course, you should not use so many techniques on one slide, and Figure 96b is intended only to illustrate the options.

FIGURE 96A It Isn't Clear where the Audience Should Focus

FIGURE 96B Options to Draw Attention to the Main Points

Tip 97: Have Support in the Room

Even if you're an expert, you can't possibly know everything. In addition to being honest about what you don't know (see Tip 111), another strategy as you prepare your talk is to have one or more people in the room to serve as backup support. For example, when discussing a large, complex project, your job is to summarize it at a high level. However, the audience might ask questions about its smaller components.

Because you weren't involved in every component, have people in the room who were. That way, if a question comes up about an area of the project you aren't prepared to cover in depth, you can turn the question over to an expert‐in‐waiting who has been briefed on the content and objectives for the meeting. This also helps demonstrate the depth of your team.

This strategy is also a great way to enable team members who are less comfortable being the lead presenter to get exposure. A large team will include some strong presenters and some weak presenters. For an important presentation, let one of your strong presenters take the lead, but have the people less comfortable serving as backup help handle tough questions.

The approach of passing questions to experts is common. A frequent example is when a politician is discussing a new initiative and then turns the podium over to an expert to answer questions. It seems prudent and natural to an audience and will not harm your credibility to follow this model. The slight distraction of changing speakers is far better than getting stumped in front of everyone, and it provides visibility for other experts, which only helps reinforce the quality of the team!

Tip 98: Always Have Several Backup Plans

When you're finalizing preparation for the big presentation, never underestimate the number of things that can go wrong! If you assume that your computer, the projector, and the audio system will work as expected, then you risk having a disaster presentation. Over the years, I have had many permutations of problems.

Once, a coworker and I were co‐presenting at a conference. She put our slides up as we started. Right as my turn to talk started, her battery died! (Don't ask me why she didn't plug in.) By the time she found her power cord, rebooted the machine, and got it connected to the projector, my 20‐minute section was complete. Luckily, I had my slide thumbnails printed (see Tips 9 and 88). I stood on the stage and said everything I had planned to say, but without the slides being projected. Ideal? No. Did it work well enough? Yes.

At another conference, I confirmed with the show's tech lead that my presentation was loaded and ready to go. He even showed me where the file was in a folder, but I didn't open it at that time. As a result, I left my computer bag in my car's trunk. Of course, when I went to present, I found that the local file was corrupted and wouldn't open. I had to run down to the car and get my computer and started 15 minutes late as a result. That is the last time I ever left any of my backup items anywhere but with me!

There are many forms of and methods for backup:

- Get to the room early to set up and deal with any issues that arise.

- Connect with the room's tech team well ahead of your session to validate that all technologies and files are as expected.

- Have a printout of your full slides and/or slide thumbnails (see Tips 9 and 88).

- Have your presentation on a USB drive.

- Have your own slide clicker because room clickers frequently don't work (see Tip 99).

- Have your presentation in an email you can forward to another computer from your phone.

- Have every type of video connection cable your computer supports, plus adapters for other types of connections that your computer doesn't support.

Even with all of those in place, something else might still go wrong (I once had a fire alarm cost me 40 of my 60 minutes as we evacuated the building). But, at least you'll be prepared for the most common problems.

Tip 99: Use a Slide Clicker

I always have my personal slide clicker in my bag. My current one only cost about $15. It is shaped like a pen and fits in my hand so that the audience can barely tell that I have it. It has a standard USB plug‐in that connects to the clicker wirelessly, so it works on virtually any computer.

A clicker gives you full control of your slides from wherever you are standing. It also avoids forcing you to return to the computer every time you want to advance a slide. In a small room, tapping the keyboard works okay because there isn't much room for you to move anyway. In most presentations, it will be a distraction. Per Tip 106, you should move around during your presentation, and needing to return to home base for every slide change will limit your ability to do so.

You should avoid having someone advance the slides for you. It is rare that a slide changer knows exactly what you'll say and when to click to advance slides seamlessly. In 99% of the presentations I've seen with an official slide changer, the speaker has to say “next slide” each time, which is distracting. Things only get worse when you need to go back a few slides and you must say “another one, another one, oops too far” until you find it. With your clicker, you can just go to the right slide.

If you use action settings (see Tip 24), then you'll need a fancier clicker with mouse functionality or you'll be forced to return to home base to make use of an action. However, actions are typically at a break point in the flow and so this isn't as distracting as usual.

Tip 100: Do Not Send Your Presentation in Advance

It is not unusual when you are preparing a presentation to be asked for a copy in advance. I know many speakers who proactively send their presentations in advance to the audience, whether requested to or not. I strongly recommend against sending anything in advance unless you are given no choice.

For example, if the executive team you are presenting to requires everyone to send slides in advance with no exception, then you are stuck. Outside of a firm mandate, offer to send out a copy as soon as the presentation is over so that any last‐minute changes will be accounted for. I typically just ignore a request for advance slides and far more often than not, the person asking forgets until I show up to the presentation. At that point, I commit to sending as soon as the meeting is over.

Why is it bad to send the slides in advance? There are several reasons:

- You want the audience to hear your story directly from you. When you send your slides in advance, they'll have already seen your punchlines, but without your narrative and context. Like knowing the punchline to a joke before it is told, the big “aha” moments you discuss won't seem so big if the audience already knows them.

- Many in the audience won't read your slides prior to the meeting but will instead spend much of the start of the meeting looking through them and ignoring you. This still has all the negatives of the prior point with the added downside of loss of attention during the presentation.

- After reading your slides, people will form opinions, draw conclusions, and even start making plans on the partial information they extract from your slides. You will now have to change their minds, which is hard to do.

- You might make last‐minute changes. It hurts your credibility and your flow to have to say, “This slide was updated and won't match what you have in front of you.”

In cases when I have been forced to send slides in advance, I start my presentation by asking people not to read through them as I talk. I explain that I'll be providing important context for the facts in the slides and that they'll get the most from the session if they consider the handout to be notes for later.

Another common situation is when an administrative assistant or technical support person asks for your slides to load them on a meeting room computer for projecting. In these cases, I'll first ask if I can just connect my computer instead. They usually say that I can and are relieved not to have to worry about anything on their end. If someone is adamant about using the equipment in the room (many conferences are), I supply the slides but ask that they only be placed on the machine in the room and not distributed beforehand. I also make clear that the raw PowerPoint version should never be shared with anyone and should be deleted from the computer when I am done. Almost everyone will comply with those requests.

Last, whenever you do share your content, be sure to include copyright and confidentiality notices at the bottom. Also, always share your content as a PDF so that nobody can edit it, whether accidentally or not, and then pass on a changed version. Make sure that only your story is shared and only as you wrote it!