“The elevator pitch to a CEO is: Take a hard look at the companies in your field that are surviving and doing well. All of them today have outstanding IT, operated effectively, which is a product of significant cooperation and understanding between line executives and IT executives.” | ||

| --Professor John F. Rockart, MIT | ||

Investing in business technology[1] should begin with the organization’s strategic position. These positions are often crafted without a clear understanding of business technology’s potential to influence or execute them. Mischaracterized as merely being “IT strategy,” efforts to guide the potential contributions of business technology are relegated to the back office where they frequently comprise little more than architecture, platform, and standards mandates. Even purported “business and IT alignment initiatives” often involve more reconciliation of separately crafted strategies than synchronization of business technology with business needs.

This chapter examines several common strategic positions and shows how business technology can support each. It shows why determining the appropriate level of business technology investment is made easier by several of the BTM capabilities,[2] including Strategic Planning and Budgeting and Strategic Sourcing and Vendor Management.

We argue that only when business technology investments are tied directly to business capabilities that enable a firm’s strategy can an organization be sure it is investing correctly. Contributing authors for this chapter are Michael Fillios, Chief Product Officer, and James Lebinski, Vice President of Knowledge Products, at Enamics, Inc.

In Brief

Only when a firm matches the level and mix of business technology and BTM investments to its strategic positioning can it know whether it is spending correctly.

Business technology is often critical in establishing or sustaining a strategic position; not understanding its roles across a firm’s product-markets can lead to inappropriate levels of investment.

Scholars studying how firms or networks of firms evolve their strategic positions have observed that two very different types of strategic actions are necessary: exploitative and exploratory.

Building lean or agile organizations requires substantial investment and carries strategic risks. It is important to realize that not all firms need to be lean or agile and that it is possible to exhibit both leanness and agility.

“Are we investing too much or too little in IT?” All too often, business technology executives answer this question with comparisons to a generic peer group—an approach that can prove increasingly counterproductive the more distinct a firm’s business strategies and tactics are from those of the peer group members. Only by matching the level and mix of business technology investments to its business strategy can an organization be sure it is investing correctly.

Moreover, only part of these investments should be for IT assets[3] such as hardware and software or their application. Equally important is investment in the BTM capabilities needed to manage the complex relationship between business technology and business needs. This means developing the processes, organizational structures, information, and automation necessary for choosing the right technology and implementing it effectively. Without this, investments in hardware alone offer little or no value, and efforts to assemble supporting business technology often are disconnected from the enterprise business strategy. A firm seeking strategic value from its business technology must ensure that its IT strategy respects and supports the business strategy.

To understand how business technology can become an integral player at the strategic level, it is helpful to briefly review the basics of strategy. A firm fabricates a strategic vision and assembles the competencies enabling it to occupy a niche in a product-market. Typically, this is done through competencies in cost leadership, product/service leadership, and/or customer leadership in a product-market.[4]

If a firm is alone in a product-market niche, this extraordinarily favorable situation typically does not last long as competitors respond to the above average returns. It is crucial, therefore, to both establish a profitable strategic position and sustain it. With today’s globalized—and, hence, increasingly competitive—marketplaces, this is more difficult than ever.

A simplified view of what occurs is depicted in Figure 2.1. Business strategists discover profitable opportunities—new market spaces or gaps in existing market spaces—by considering (1) signals regarding product/service, customer, technology, socioeconomic and cultural trends; (2) competitors’ current and future strategic positions; (3) the firm’s internal competencies; and (4) recognition of the competencies it might gain access to through partners.

Companies discover market opportunities by considering internal competencies and external signals.

Figure 2.1. Establishing Strategic Positions

A firm’s initial position in the product-market must then be regularly augmented such that it continues to offer a value proposition beyond those provided by competitors. As is explained later in this chapter, business technology often plays a critical role in establishing a strategic position or in sustaining it once established; not understanding these roles across each of a firm’s product-markets can—and often does—lead to inappropriate levels of business technology investment. By giving visibility to the particulars of a firm’s business strategy and the technology resources deployed to achieve it, BTM[5] allows firms to gain that understanding.

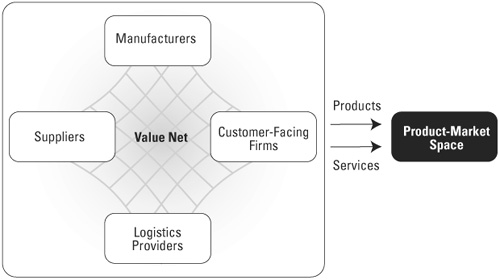

Invariably, today, strategic positions are forged not by single firms but rather from leveraging the distinctive competencies of a number of firms (see Figure 2.2). The BTM capability of Strategic Sourcing and Vendor Management recognizes this, and defines the approach for creating and managing these relationships. This includes identifying areas of strategic opportunity for outsourcing, co-development, and vendor selection. By each strategic partner nurturing its distinctive competencies to world-class levels and by tightly coordinating partner activities, these networks of cooperating firms, or “value nets,” can continuously improve their value propositions or engage radically transformed or newly created product-markets.[6]

Strategic positions are often forged by coupling the competencies of multiple firms.

Figure 2.2. Value Nets

Scholars studying how firms or networks of firms develop their strategic positions have observed that two very different types of strategic actions are necessary: exploitative and exploratory.[7] Exploitative actions refer to continuously improving the competencies associated with an existing strategic position. The string of initiatives taken by Wal-Mart during the 1990s to drive costs out of its supply chains is an example. Exploratory actions, on the other hand, refer to discovering new strategic positions or new competencies that might be instrumental in creating radically transformed or new strategic positions. An example is the string of anything-but-systematic initiatives taken by Dell during the 1990s in arriving at its Direct Model.

Exploratory strategic actions create new product-markets. After a new product-market is created, firms with favorable strategic positions in it strive to exploit their position to sustain it. Known and unknown competitors, however, engage in exploratory actions to supplant this position. If an exploiting firm is inattentive to the behaviors of exploring firms, it can be locked out of these emerging but highly attractive product-market niches.[8]

Exploitation has been a hallmark of industrial competitiveness over the past two decades, encompassing movements such as Total Quality Management, Lean Manufacturing, and Six Sigma. With such initiatives, the intent is to delight customers by eliminating defects and waste (in materials, methods, processes, time) and thereby delivering high-quality products and services at low cost and in a timely manner. Through such regular, incremental improvements, favorable strategic positions can be continuously refined, enhanced, and sustained.

Generally, a firm becomes lean by accumulating experience, data, and knowledge about the work environment and exploiting these to improve efficiency and effectiveness.

Concern with exploration has intensified along with the increased competitiveness of the global economy and the increasing rates of scientific progress. With increased competitiveness, it becomes difficult to sustain a favorable strategic position as existing competitors are motivated to quickly match or best the position and as new competitors are motivated to enter the product-market. With increased scientific progress, the technological basis of a favorable strategic position is more quickly eroded. By being agile, a firm is able to sense and respond to competitors’ strategic moves within existing product-markets, as well as sense and respond to environmental signals arising from shifts in customer desires or in new technologies. Firms demonstrate strategic agility in four major ways:

They continuously scan their environment to identify threats to existing positions and opportunities to forge new positions.

They regularly engage in strategic experiments. That is, they implement small-scale strategic initiatives to perturb internal or external work environments to gain experience with emerging technologies, work practices, product, or service concepts, customer segments or product-markets.

They devise adaptive business architectures so that their competitive assets (as well as those of partners) can be realigned quickly—shutting down activities, commencing new activities, or shifting resources among activities.

They learn to radically renew the competencies that characterize their competitive nature.

The Strategic Planning and Budgeting capability can prepare an organization to examine how it will use business technology to enable its exploitative and exploratory strategic actions. This is illustrated in Table 2.1 for four classes of business technology investments focused respectively on a firm’s transactions, decisions, intellectual capital, and relationships. Understanding these classes of investments helps in understanding how BTM contributes to the forging of exploitative and exploratory strategic actions.

Table 2.1. Enabling Strategic Actions Through Business Technology Investments

Transaction-focused investment facilitates exploitation by handling business transactions (both within an enterprise and with external parties) faster and more reliably (that is, fewer errors or steps), thereby increasing productivity and responsiveness as well as lowering costs. Transaction-focused investment facilitates exploration by increasing both the number of potential parties with whom transactions can be executed and the potential types of transactions that can be handled, as well as by increasing the visibility of transactional events across the extended enterprise. This last point has become extremely important today with most firms finding themselves having to expose data about key business events—orders, deliveries, low inventory levels—to customers or suppliers and likewise expecting their strategic partners to do the same. With increased information visibility across supply chains and value nets, business models and value propositions that were unimaginable only a few years ago have become the norm.

Decision-focused investment facilitates exploitation by enabling decision automation through the embedding of decision rules within software as well as by providing employees with enhanced information and proven decision filters for decision situations that are not automated. Decisions are made faster, more reliably, and more completely, thus increasing decision quality and responsiveness as well as employee productivity. This lowers costs and better aligns products and/or services with customer requirements. Decision focused investment facilitates exploration by enabling decision authority to be distributed more widely, by increasing the number of perspectives brought to bear on a decision, and by allowing more discretion to employees closest to a decision. Emerging opportunities are more likely to be recognized, interpreted from a variety of perspectives, and acted on.

Intellectual capital-focused investment facilitates exploitation by codifying, archiving, making accessible, embedding in processes and decision schemas, and transferring across the firm the knowledge that has been acquired and created. This use of knowledge regarding the firm’s product-markets, as well as the assets and activities needed to enhance strategic positions in them, produces deeper, more consistent thought, purpose, and ability across the firm. Intellectual capital–focused investment facilitates exploration by extending a firm’s “intelligence at the edge.” It does this by enhancing sensing and interpretation, increasing the number and variety of accessible external sources of knowledge, increasing firm-wide visibility into what is happening at the firm’s edges, and enabling specialized knowledge sources to be easily established, promoted and accessed.

Relationship-focused investment facilitates exploitation by tightening relationships across a firm and between a firm and its trusted partners. Within a firm, it provides collaborative work environments in which the insight of all employees involved in fashioning and maintaining a strategic position can be brought to bear without regard for time, location, or positions. Externally, it creates resilient links with partners that enable the firm’s ability to work with them and understand them better. Relationship-focused investment facilitates exploration by broadening relationships across a firm and with partners and allowing them to be easily formed or disbanded. As a consequence, a breadth of assets, skills, and competencies become available to identify, assess, and act on opportunities. Just as important, those associated with underperforming positions can be reassigned or eliminated.

To illustrate the many and varied roles served by business technology and supporting investments, consider the action initiated by Herman Miller in the late 1990s to stake a strategic position in an underserved market—that of offering small businesses no-frills, quality furnishings delivered quickly at a reasonable price.[9] In accomplishing this strategic initiative, Miller established a new operating unit, Herman Miller SQA (Simple, Quick and Affordable), and introduced a flurry of innovations that have since migrated into the parent company:

Local dealers are provided with innovative 3D visualizing tools and product configurators that are used in consulting with customers about a potential order—furniture, design styles, fabrics, wood finishes, space layout, and so on (decision-, intellectual capital-, and relationship-focused business technology investments).

When the dealer and customer have reached agreement on an order, the software creates an order list with all parts and the final price (decision- and transaction-focused investments).

As soon as the order is accepted, it is sent via the Internet to a Miller SQA manufacturing facility, where it enters production and logistics scheduling systems. Within two hours, the dealer and customer receive confirmation of delivery and installation dates (decision-, relationship-, and transaction-focused investments).

Miller SQA’s supply net transparently links its many suppliers to its operations, streamlining purchasing, inventory, and production processes. Here, the 500 suppliers are provided visibility into the data in Miller SQA’s systems and are expected to automatically send more materials when needed (decision-, relationship-, intellectual capital-, and transaction-focused investments).

By applying business technology exceptionally well in both exploitative and exploratory ways, Miller SQA reduced an industry order cycle of about 14 weeks to about 2 weeks and, in the process, redefined what was required for competitive success in this product-market niche.

At first glance, the Herman Miller example belies the notion that technology assets are, for the most part, commodities. However, with a deeper look, it becomes clear that success was achieved from more than IT investment alone. True success came from imbuing these assets with firm-specific structure and content, and by embedding these within business architectures enabling business strategies to unfold, and by providing careful management of these assets through a well-honed set of BTM capabilities. In this way, these “commodities” can be transformed into value-adding assets.

How does a firm like Herman Miller determine appropriate investment levels? One approach to answering this question begins with the firm’s strategic learning orientation.

Statements extolling the desirability of being lean, being agile, or both reverberate throughout the business press and strategic consultancies. However, building lean or agile organizations requires substantial investment and carries strategic risks. A lean firm can become blind to the emergent opportunities that eventually overtake a favorable strategic position; an agile firm can lack the discipline required to sustain a favorable strategic position.

It is important to realize that not all firms need to be lean or agile. Figure 2.3 provides a way to think about this based on the organizational learning orientation (that is, the types of learning behaviors emphasized and required by the nature of the product-market within which a firm has taken a strategic position). Two very distinct strategic learning orientations exist:

Single-loop learning refers to the efforts taken to continuously monitor performance against plan, learn from deviations, and embed this learning in action. Single-loop learning is most effective for a relatively stable business environment where new understanding can be accumulated and aggressively applied in improving performance. Such a learning orientation is necessary in furthering exploitative, or lean, strategic actions. For example, single-loop learning has been turned into an art form by firms such as McDonalds, whose business model involves determining the most efficient operational processes within a fast-food environment and then replicating this best practice across all it retail outlets.

Double-loop learning refers to continuously challenging assumptions about a given operating area and quickly adjusting operating practices when the assumptions are proven invalid. Double-loop learning is most effective for a relatively dynamic business environment. Such a learning orientation is necessary in furthering exploratory, or agile, strategic action. For example, double-loop learning has been turned into an art form by firms such as Benetton, whose business model involves understanding the frequent shifts in global and local fashion trends in order to quickly emphasize hot product lines, drop cold product lines, and design new product lines in response to current or emerging tastes.

Different levels of product-market competitiveness and stability require different strategic positions and levels of business technology investment.

Figure 2.3. Strategic Positions Vary with Market Conditions

Four categories of product-markets are depicted in Figure 2.3. Note the dollar signs, which indicate the relative business technology investment required to maintain strategic positions in each.

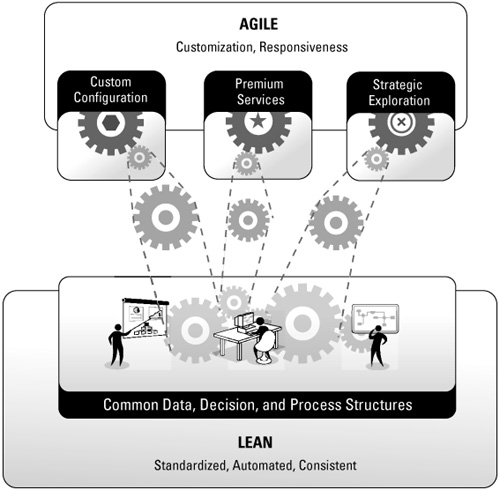

The status quo cell in Figure 2.3 is intuitive. If a strategic position enjoys little competition and exhibits stability over time, then few, if any, strategic actions need to be implemented to sustain it. Historically, firms in highly regulated industries or isolated geographic areas enjoyed the luxury of holding a status quo market position. It is not that being lean or being agile is “bad” for firms in this status quo cell, but rather that the significant investments required to become lean or agile are not necessary. Finally, the fourth quadrant—“leagility” (that is, lean and agile)—at first glance might seem contradictory. Given these very different firm behaviors (each of which require distinctive business architectures), can a firm be both lean and agile? Manufacturing theorists argue that with appropriately designed business systems, it is quite possible to exhibit both leanness and agility.[10] The manufacturing solution involves designing decoupling points into supply chains such that upstream from the decoupling points processes are lean, whereas downstream processes are agile. In other words, upstream work processes are highly optimized and tightly integrated; however, downstream processes are customized and only loosely integrated via selective data sharing with other work processes. For example, if assembly is postponed until customer orders are received, then customized assembly operations can respond to specific customer requests; but the upstream inbound logistics and component manufacturing activities can be very lean. Thus, activities prior to the decoupling point are “push driven” by forecasts and designed to be as efficient as possible, whereas activities after the decoupling point are “pull driven” and designed for customization and responsiveness.

Applying similar architectural design principles, Figure 2.4 depicts how a firm might fabricate a very exploitative architecture consisting of common, tightly coupled data, decision, and process structures but then insert decoupling points to a variety of loosely coupled architectural environments that allow for more exploratory strategic actions. Consider, for example, the business architecture supporting a technical call center. Most customer support calls involve either quite routine problems or are from customer segments providing low profitability margins. As a result, very lean, automated business architectures are commonly applied via an archived problem solution repository accessed directly by customers via a Web interface or through customer support representatives following tightly written scripts. However, the processes used in dealing with unusual, highly technical problems or from customer segments providing high profit margins are typically decoupled from this very lean business. Although the investment in designing, implementing, and evolving such ambidextrous business architectures is high, the advantage of being able to maintain favorable strategic positions in competitive, dynamic product-markets far outweighs the cost.

The heated debates throughout the 1990s regarding the “IT productivity paradox” seems to have dissipated with the general acceptance of two insights:

IT assets (hardware, software, communication networks, and so on) by themselves add little, if any, economic value.

The added-value nature of IT assets materializes through their appropriate use in fabricating business platforms that deliver products or services and business solutions that address emergent opportunities and problems. An appropriate use of business technology reflects (1) that investments are based on sound business cases; (2) that complementary investments (in data collection and organization, business process redesign, employee skill development, employee incentive structures, and so forth) are executed; and (3) that the business technology-related activities associated with investment initiatives are themselves well executed. For these three conditions to be met, a management standard, such as the BTM Standard fusing business and technology acumen, must exist.

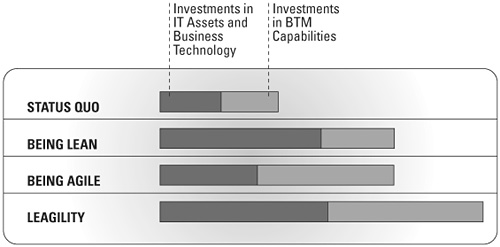

An additional insight follows directly from the recognition that there are actually three forms of investment—IT assets (for example, hardware and software), business technology (applying these IT assets to meet business needs), and BTM (managing business and technology together)—and the realization that different product-markets are likely to involve very different levels of investment.

Desired levels of investment in IT assets, business technology, and in BTM capabilities vary depending on the strategic learning orientation of the targeted product-market. As a result, in applying business technology to develop or sustain strategic positions, firms may very well be underinvesting or overinvesting in IT assets, business technology, or in BTM capabilities, or in all three, even though they might benchmark well with other firms.

Figure 2.5 contrasts IT, business technology, and BTM capability investment levels across the four product-market situations. As might be expected, the lowest investment levels would be seen with firms focused on maintaining the status quo, and the largest would be seen with firms having to build the ambidextrous business architectures associated with leagility. The investment in IT assets and business technology required by a lean strategic posture is likely to be greater than that to maintain an agile posture because the emphasis on optimizing work processes via common process and data models requires substantial investment and reinvestment in interoperable technology platforms. However, investments in BTM capabilities are very likely to be greater for firms building and evolving agile strategic postures because of (1) the firm-specific, action-specific nature of the roles served by business technology in enabling strategic actions and (2) the requirement that management capabilities—in particular, BTM capabilities—be exercised across a constant stream of new product-market positions and innovative strategic actions.

The ratio and relative level of investments in IT, business technology, and BTM capabilities will differ depending on a firm’s strategic orientation.

Figure 2.5. IT/Business Technology and BTM Capability Investment Levels

Figures 2.6 and 2.7 depict how investment levels in IT/business technology and BTM capabilities might be expected to differ in supporting these four product-market situations. In Figure 2.6, the lowest level of investment is had with the lower-left cell (neither lean nor agile) and the greatest level of investment is had with the upper-right cell (both lean and agile). Also, the arrows in the figures indicate that the investments in a target cell (for example, upper left) also include the investments in a source cell (for example, lower left). In Figure 2.7, an organization operating in the status quo quadrant will typically focus on the highlighted BTM capabilities, while prioritizing the development of others. Operating in, or moving toward, the agile or lean quadrants requires that the organization expand its focus to include additional BTM capabilities, while still prioritizing the development of others. Finally, moving toward the Leagility quadrant means that all of the BTM capabilities must be developed to achieve and maintain this strategic orientation.

The types of IT and business technology investments will vary depending on a firm’s strategic orientation.

Figure 2.6. IT and Business Technology Investment Mixes

How a firm prioritizes its investments in BTM capabilities will vary depending on its strategic orientation.

Figure 2.7. BTM Capability Investment Mixes

As a firm discovers through BTM the right level and mix of investments, it will also discover whether its IT function has the depth and expertise to deliver what is expected—a large and complex firm requires a higher level of sophistication in its technology. Size and complexity also suggest much greater potential benefit from effective BTM.

| 1. | See the “Key Terminology” section in Chapter 1. |

| 2. | Ibid. |

| 3. | Ibid. |

| 4. | Treacy, M. and Wiersma, F. D. The Discipline of Market Leaders: Choose Your Customers, Narrow Your Focus, Dominate Your Market. Addison-Wesley, 1995. |

| 5. | See the “Key Terminology” section in Chapter 1. |

| 6. | Premkumar, G., Richardson, V. J., and Zmud, R. W. “Sustaining Competitive Advantage through a Value Net: The Case of Enterprise Rent-A-Car.” MISQ Executive (December 2004), 189–199. |

| 7. | O’Reilly, C. A. III. and Tushman, M. L. “The Ambidextrous Organization.” Harvard Business Review (April 2004): 74–81. |

| 8. | Christensen, C. M. The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, 1997. |

| 9. | Prahalad, C. K. and Ramaswamy, V. The Future of Competition. Harvard Business School Press, Boston 2004; Rocks, D. “Reinventing Herman Miller.” Business Week. On-Line, April 3, 2000. |

| 10. | Van Hoek, R. I. “The Thesis of Leagility Revisited.” International Journal of Agile Management Systems (Vol. 2, No. 3, 2000) 196–201. |