“Convergence has been the Holy Grail of leaders for a long time. The key is to recognize that it is a journey and not an event.” | ||

| --Professor John Henderson, Boston University | ||

Over the past few years, a standard for the management of business technology has emerged—a repeatable set of processes, defined in terms of 17 business capabilities, that lead to intelligent and consistent business technology management. This chapter sets forth the particulars of this Business Technology Management (BTM) Standard and argues that it is not only a solution for the problems that plague technology deployment, but also a competitive advantage for firms that adopt it.

In Brief

The BTM Standard provides a set of guiding principles that create a seamless management approach that begins with board- and CEO-level issues and connects all the way through technology investment and implementation.

The Standard identifies 17 essential capabilities grouped into four functional areas: Governance & Organization, Managing Technology Investments, Strategy & Planning, and Strategic Enterprise Architecture.

The BTM Maturity Model identifies areas most in need of improvement, fixes the starting point for the enterprise, and specifies the path for change.

The right way to approach BTM implementation is iteratively. An enterprise must determine where it is in order to focus on specific priorities, design and implement specific capabilities against those priorities, and then execute and continuously improve.

In today’s world, to manage the business well is to manage technology well. And vice versa.

By now, we certainly know what happens when business and technology are managed on two different tracks. Companies spend 10 percent to 40 percent of their revenues on technology and often just can’t shake that sinking feeling that something is wrong.

Hundreds of millions spent by big-name companies on enterprise resource and customer relationship systems have been wasted; nobody thought to redesign underlying work processes or to make sure employees understood what was happening and why. Huge business technology expenditures to lubricate the supply chain of a global apparel maker managed only to wrap that chain around the axle, leaving the company worse off than if it had done nothing at all. As one CEO said in exasperation, “Is this what we get for our $400 million?”

Such expensive failures have led many observers to question whether information technology can ever produce a defensible long-term competitive advantage.

Unquestionably, there have been enough successes to whet the appetite for the rewards of getting it right. In the late 1990s, for example, Herman Miller began offering small businesses no-frills, quality furnishings delivered quickly at a reasonable price. It established a new operating unit, Herman Miller SQA (“Simple, Quick and Affordable”). By applying business technology exceptionally well, it reduced an industry order cycle of about 14 weeks to about 2 weeks. Sears Home Services consolidated all of its information systems to manage its 12,000 service people. Everything is automated and wirelessly connected. The result is huge savings in parts management, huge increases in productivity of their service people, and significant increases in customer satisfaction.

But on the flip side of exceptional success lies precipitous (or perhaps worse, incremental and undetected) failure. The results have been manifest in productivity shortfalls, imposed workforce reductions, damaged corporate reputations and downward market valuations.

These outcomes threaten to marginalize technology’s role in value creation at the very time that it should be brought closer to the business than ever before. Instead, we are seeing chief information officers reporting to the CFO rather than the strategy office or CEO. More symptoms: a headlong rush to outsource business technology, and choke-holds on technology spending, without any truly strategic understanding of either move. With that often comes a pattern of serial CIO—and maybe CEO—replacement, which virtually guarantees that short-term thinking will rule. What appears at first blush to be the fault of the technologist (“Can’t you make this stuff work?”) is really a failure to unify business and technology decision making.

For many enterprises or operations, alignment of business technology with the business has been considered the Holy Grail. Alignment can be defined as a state where technology supports, enables, and does not constrain the company’s current and evolving business strategies. It means that the IT function is in tune with the business thinking about competition, emerging threats and opportunities, and the business technology implications of each. Technology priorities, investments, and capabilities are internally consistent with business priorities, investments, and capabilities.

When that’s the case, the company has reached a level of BTM that relatively few have achieved to date. Alignment is a good thing, and sometimes sufficient to serve a particular business situation.

But there are higher states to consider (see Figure 1.1), and for some enterprises, synchronization of technology with the business is the right goal. At this level, business technology not only enables execution of current business strategy but also anticipates and helps shape future business models and strategy. Business technology leadership, thinking, and investments may actually step out ahead of the business (that is, beyond what is “aligned” with today’s business). The purpose of this is to seed new opportunities and encourage far-sighted executive vision about technology’s leverage on future business opportunities. Yet the business and technology are synchronized in that the requisite capabilities will be in place when it is time to “strike” the strategic option.

The three states of alignment, synchronization, and convergence demonstrate different relationships between business and technology.

Figure 1.1. Alignment, Synchronization, Convergence

Finally, there is the state of convergence, which assumes both alignment and synchronization, with technology and business leadership able to operate simultaneously in both spaces. Essentially, the business and technology spaces have merged in both strategic and tactical senses. A single leadership team operates across both spaces with individual leaders directly involved with orchestrating actions in either space. Some activities may remain pure business and some pure technology, but most activities intertwine business and technology such that the two become indistinguishable.

Is this actually possible? Quite so. Examples are abundant for alignment, less so for synchronization, and still fairly rare for convergence. More important, however, how does an enterprise decide what state it should be pursuing, and how does it get there?

Business Technology Management (BTM) is an emerging management science, grounded in research and practice, that aims to unify decision making from the boardroom to the IT project team. The standard described in this book and put forth by the BTM Institute provides a structured approach to such decisions that lets enterprises align, synchronize, and even converge technology and business management, thus ensuring better execution, risk control, and profitability.

Companies have employed a number of methodologies and techniques to improve business and technology alignment. Although many of these methods have acknowledged strengths, they represent piecemeal solutions.

Disparate islands of practice exist within the technology management domain (see Figure 1.2), particularly in the areas of operations and infrastructure. These range from the Software Engineering Institute’s Capability Maturity Model (CMM) to PMI’s Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK) and the IT Infrastructure Library (ITIL) for services management. However, none of these approaches focuses on integrating and enabling the capabilities necessary to achieve strategic business technology management and the sustainable value that follows. But the danger of relying solely on downstream technology management methodologies is that by the time misalignment becomes apparent, it may be irreversible.

BTM integrates and enables the capabilities necessary to achieve strategic business technology management.

Figure 1.2. Other Management Frameworks

The BTM Standard provides a set of guiding principles around which a company’s practices can be organized and improved. It builds bridges between previously isolated tools and standards for business technology management. Essentially, BTM sits strategically above operational and infrastructure levels of technology management. The standard aims to create a seamless management approach that begins with board and CEO-level issues and connects all the way through technology investment and implementation.

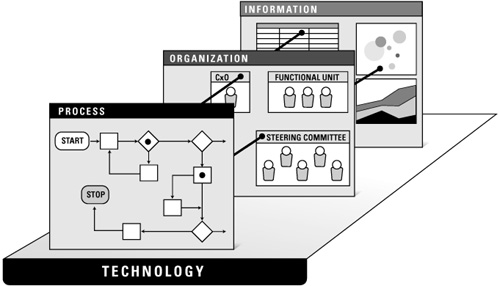

The BTM Framework identifies 17 essential capabilities grouped into functional areas: Governance & Organization, Managing Technology Investments, Strategy & Planning, and Strategic Enterprise Architecture. These capabilities are defined and created by four critical dimensions: processes, organization, information and technology (see Figure 1.3).

As illustrated in Figure 1.4, the first dimension for institutionalizing BTM principles is a set of robust, flexible, and repeatable processes. Simply defining these processes is insufficient, however. To effectively implement BTM requires that processes be evaluated to ensure the following:

General quality of business practice. —Doing the right things

Efficiency. —Doing things quickly with little redundancy

Effectiveness. —Doing things well

The four critical dimensions of BTM are processes, organization, information, and technology.

Figure 1.4. Critical Dimensions of BTM

Management processes are more likely to succeed when they are supported by appropriate organizational structures based on clear understanding of roles, responsibilities, and decision rights. Such organizational structures generally include the following:

Participative bodies, which involve senior-level business and technology participants on a part-time but routine basis

Centralized bodies, which require specialized, dedicated technology staff

Needs-based bodies, which involve rotational assignments, created to deal with particular efforts

The right set of structures will vary according to an enterprise’s value discipline, its primary organizational structure, and its relative BTM maturity. Centralized bodies, such as an Enterprise Program Management Office (EPMO), tend to require specialized, dedicated staff. Participative bodies, such as a Business Technology Investment Board, are ongoing, part-time assignments for their participants—the key stakeholders. Needs-based bodies—functionally specialized groups such as project teams—tend to be rotational assignments created in response to particular needs. These bodies set direction, guide specific business technology activities, and systemically execute against approved plans.

Valid, timely information is a prerequisite for effective decision making. This information must be delivered in a way that is comprehensible to non specialists and, at the same time, actionable in terms of informing choices that matter. Useful information does not just happen. It depends on the interaction of two related elements: data and metrics.

Data must be available, relevant, accurate, and reliable. Metrics distill raw data into useful information. Thus, metrics need to be appropriate and valid for strategic and operational objectives. Internally, they should be comparable across the enterprise and across time; and externally across industries, functions, and extended-enterprise partners.

Management processes based on flawed information will fail when confronted with conditions that exploit the flaws. As an illustration, consider a major retailer of auto parts that spends millions acquiring and analyzing customer data to determine where their customers live. The retailer then sites new stores in strip malls near these neighborhoods only to be disappointed to discover the new stores’ sales lag the older stores. As it turns out, “where the cars live” is a poor predictor of success compared to “where the cars work.” Locating stores along major routes to and from primary employers would produce much better results. As this example illustrates, flawed information need not be incorrect—just inappropriate for the intended use.

Effective technology (that is, management automation tools) can help connect all the other dimensions. Appropriate technology helps make processes easier to execute, facilitates timely information sharing, and enables consistent coordination between elements and layers of the organization. It does this through the following:

Automation of manual tasks

Reporting

Analytics for decision making

Integration between management systems

The simple addition of technology to automate existing processes leaves most of its potential value untapped. The largest gains result from the optimization of processes, organizational structures, and information flows. The complexity of managing the business technology function and increasing demands of an ever-evolving business climate require more information transparency and operational synchronization than basic computing tasks can provide. The appropriate use of technology should not only ease the development and reporting of information needed to fuel management processes across the organization, but also to achieve consistent horizontal and vertical management integration.

A BTM capability is therefore defined as a competency achieved by applying well-defined processes, appropriate organizational structures, information, and supporting technologies in one or more functional areas. Successfully implementing any of these capabilities will move an organization closer to the goal of business and technology unification. This progress accelerates as each additional capability is realized and continuously improved.

The 17 capabilities are interrelated and interdependent or “networked.” All of them should be implemented to maximize the business value of technology investments. But doing so requires a carefully orchestrated approach with top-down and bottom-up support. It also involves business and technology groups in equal measure—plus hard work and time, of course.

These 17 capabilities are grouped into the functional areas described in more detail next: Governance & Organization, Managing Technology Investments, Strategy & Planning, and Strategic Enterprise Architecture (see Figure 1.3).

This functional area is focused on enterprise CIOs and business executives concerned with enterprise-wide governance of business technology. The capabilities that must be developed to support this functional area ensure that required decisions are identified, assigned, and executed effectively. Necessary capabilities also include the ability to design an organization that meets the needs of the business, manages risk appropriately, and gives proper consideration to government, regulatory, and industry requirements. Four capabilities constitute the Governance & Organization functional area:

The Strategic and Tactical Governance capability establishes what decisions must be made, the people responsible for making them, and the process used to decide. This relates to a full range of business technology governance issues, investment decisions, standards and principles, as well as target business and technology architectures.

The Organization Design and Change Management capability establishes the makeup of work groups, defining and populating levels, roles, and reporting relationships to enable technology-based business initiatives. This capability also supports structuring and administering organizational and individual incentives as well as designing programs to foster quick and effective adoption of change.

The Communication Strategy and Management capability establishes overall strategy and tactics for creating broad-based understanding and getting actionable information throughout the organization. In particular, this capability facilitates the management of communications associated with large-scale change programs and business-technology synchronization.

The Compliance and Risk Management capability ensures that government and regulatory requirements are understood and met with regard to business technology initiatives and that appropriate risk mitigation strategies are in place.

This functional area focuses on the Enterprise Program Management Office (EPMO) and other technology and business executives who are concerned with ensuring selection and execution of the right business technology initiatives. The capabilities that must be developed to support this functional area ensure that the organization understands what it owns from an IT standpoint, what it is working on, and who is available. The organization must make certain that business technology investment decisions are closely aligned with the needs of the business and that technology initiatives are executed using proven methodologies and available technology and IP assets. Four capabilities constitute the Managing Technology Investments functional area:

The Portfolio and Program Management capability identifies, organizes, and manages existing IT assets and projects. This capability is focused on effective program monitoring and execution. This includes the development of enterprise project and asset portfolios along with appropriate reporting.

The Approval and Prioritization capability determines the criteria used for evaluating alternatives, specifying the evaluation process, and prioritizing technology investments. The creation of enterprise business cases and the definition of appropriate selection criteria and mechanisms are thereby enhanced.

The Project Analysis and Design capability drives technology-enabled business improvements and leverages re-usable IT assets. This allows the integration of Enterprise Architecture (EA) and governance with a system development life cycle (SDLC).

The Resource and Demand Management capability is used to quantify, qualify, and manage business technology demand and resource requirements. It supports and promulgates the process for categorizing and prioritizing business technology requests to ensure that they are consistent with required business capabilities, priorities, budgets, and capacity. This capability also guides the allocation of high-value scarce resources.

This functional area focuses on enterprise CIOs, divisional CIOs, and business executives who are responsible for the efforts to synchronize business technology with the business. The capabilities that must be developed to support this functional area ensure that a target set of applications will meet the needs of the business and reduce overall complexity. In addition, annual planning and budgeting must incorporate elements of business technology strategy and other evolving needs of the business. Four capabilities constitute the Strategy & Planning functional area:

The Business-Driven IT Strategy capability articulates required business capabilities and the technology plans to enable them. This allows an organization to translate business strategy into specific required business capabilities. It defines principles to guide decisions on applications and infrastructure and supports plans for moving from as-is to target architectures.

The Strategic Planning and Budgeting capability is necessary to define and link plans and budgets to strategy and enterprise architecture. Goals, milestones, and contingencies are identified and highlighted, as are planning assumptions and prerequisites.

The Strategic Sourcing and Vendor Management capability deals with creating and managing relationships with those vendors best suited to an organization’s strategy. This includes identifying areas of strategic opportunity for outsourcing, co-development, and vendor selection.

The Consolidation and Standardization capability integrates accumulated or acquired IT units and assets to ensure consistency with an organization’s strategy. This delivers improved performance by rationalizing the number of projects, assets, sites, and processes. It also extends to identifying which assets to eliminate, consolidate, or enhance, and which to standardize on.

This functional area focuses on the Office of the Chief Technology Officer and business and technology executives who are concerned with the overall architecture and standards for the enterprise. The capabilities that must be developed to support this functional area ensure that appropriate information and documentation exists to describe the current and future-state environments. Also, it is necessary to verify that business and technology people can implement strategies and plans and make recommendations simplifying the existing business technology environment. Five capabilities comprise the Strategic Enterprise Architecture functional area:

The Business Architecture capability is used to describe the business strategies, operating models, capabilities, and processes in terms actionable for business technology.

The Technology Architecture capability defines the applications and technical infrastructure required to meet enterprise goals and objectives. This includes the creation of application models, data models, as well as associated technical infrastructure models for the enterprise.

The Enterprise Architecture (EA) Standards capability is necessary to define standard business technology applications, tools, and vendors. This capability centers on the delivery of EA guiding principles, plus assessing and defining other governance requirements. Also included are standards for IT vendors and reusable assets, including design patterns and services.

The Application Portfolio Management capability is employed to establish and manage portfolios of applications, consistent with IT strategy, and to achieve target architectures and maintain standards.

The Asset Rationalization capability applies enterprise architecture and standards to simplify the infrastructure. This reduces complexity and cost by controlling the number of applications and systems.

Given the interconnectedness of the 17 capabilities and the importance of approaching them on a clear priority basis, it is critical that an organization understand its maturity relating to them. The BTM Maturity Model (see Figure 1.5) defines five levels of maturity, scored across the four critical dimensions described previously: process, organization, information, and technology.

The BTM Maturity Model identifies areas most in need of improvement, fixes the starting point for the enterprise, and specifies the path for change.

Figure 1.5. The BTM Maturity Model

A maturity model describes how well an enterprise performs a particular set of activities in comparison to a prescribed standard. This instrument assists in levying a grade based on objective, best practice characteristics. A maturity model also makes it possible for an enterprise to identify anomalies in performance and benchmark itself against other companies or across industries. The measurement of BTM capabilities through the BTM Maturity Model identifies areas most in need of improvement, fixes the starting point for the enterprise, and specifies the path for change.

A growing body of BTM Institute and Enamics research shows that at level 1, enterprises typically execute some strategic business technology management processes in a disaggregated, task-like manner. A level 2 organization exhibits limited BTM capabilities, attempts to assemble information for major decisions, and consults IT on decisions with obvious business technology implications. Enterprises at level 3 are “functional” with respect to BTM, and those at level 4 have BTM fully implemented. Organizations achieving level 5 maturity are good enough to know when to change the rules to maintain strategic advantages over competitors who themselves may be getting the hang of BTM.

The evidence shows that enterprises at lower levels of maturity will score lower for business technology productivity, responsiveness, and project success than enterprises at higher levels. As BTM maturity extends past level 3, the resulting synchrony of business strategy and technology delivery makes the enterprise more agile and adaptable. For such companies, changes in the business landscape impel appropriate adjustments to strategy and corresponding action without major disruptions or anguish.

Emerging opportunities are sensed and addressed more quickly. Project execution to deliver new capabilities is more sure-footed. As joint management of business and technology improves, the maturity of the enterprise is reassessed to focus the next set of priorities. As gains result from BTM, remaining weaknesses become more obvious and the business case for addressing them becomes more compelling.

But where to start? The job of implementing 17 BTM capabilities and measuring progress using the BTM Maturity Model can seem overwhelming. After all, every enterprise starts from a different place, with existing investments in systems and business processes that make starting over virtually impossible.

So don’t start over. Start anywhere.

The right way to approach BTM implementation is iteratively. Fundamentally, an enterprise must determine where it is in order to get focused on specific priorities, design and implement specific capabilities against those priorities, and then execute and continuously improve.

You not only can, but you actually must begin by recognizing where the enterprise stands with regard to BTM maturity. Only by respecting what is can you make real progress toward what is to be. Then you cycle again, using five steps to continuous BTM improvement (see Figure 1.6):

Establish a Baseline (assess BTM maturity levels, confirm opportunity areas, identify high-priority functional areas and key stakeholders).

Educate and Align (educate key stakeholders on BTM capabilities, review baselines, and develop consensus on roadmap).

Diagnose and Design (analyze and define the scope of the problem, identify relevant components of the BTM Framework, design processes, organization, information, and automation).

Realize and Mobilize (implement the design with best practice templates, operationalize repeatable decision-making processes).

Optimize and Maintain (fine-tune management processes, update information, and ensure decision quality).

The flexibility of this approach provides multiple points of entry into a BTM roadmap, with or without previous BTM experience. This eliminates any need to completely recast the existing approaches in an organization. BTM maturity initiatives are easily blended with and serve as a supporting framework that can organize and improve existing practices. Incumbent tools and standards for technology management are integrated into the holistic BTM Framework.

The flexible nature of BTM and its implementation cycle easily interfaces with external sources such as compliance studies, management consulting engagement outputs, and audits. Regardless of the source, virtually any baseline or starting point will support the identification of target activities appropriate to an organization’s current environment and its state of business and technology synchronization.

As a company approaches the successful conclusion of a BTM improvement cycle, it will be simultaneously planning the evolution of its BTM maturity. This is accomplished by observing results and preparing to establish the next performance baseline. Ultimately, a company operating in the “execution and improvement” zone will seek to revisit their baseline and to determine areas of focus for the next cycle of BTM progress.

Smart enterprises today are rightfully pursuing alignment of technology with the business, and that in itself is no small achievement. But for some, the right level is really synchronization, where technology shapes (not just enables) strategic choices. And at the highest level of achievement, business and technology leadership actually converges, reflecting an executive and management team that has achieved an extraordinary level of cross-understanding and vision for the future.

The BTM Standard supports enterprises at all three levels. Assembling the components of Business Technology Management as described previously yields unprecedented capacity and opportunity for success in a marketplace where competitive advantage is increasingly defined through technology.

Business technology budgets are so big today that they obviously cannot be ignored by any senior management team. There are those companies with executives who will wring their hands, clamp down with arbitrary spending caps, demand a quick fix such as outsourcing, and call for the head of the CIO. Within a short while, they will cycle through those steps again, since nothing there addresses the core issue: You cannot spend (or slash) your way to business technology excellence and congruence with the business. That demands intelligent application of technology, with spending determined by strategic business needs, not by arbitrary benchmarks.

In fact, there are companies whose executives are beginning to see that business technology investment must be accompanied by appropriate BTM investment. This new kind of capital includes the processes, organizational structures, information and technology required for unified business and technology decision making. This new kind of company will move beyond alignment, where technology supports but never goes beyond immediate business needs, to synchronization and convergence, where technology helps shape new opportunities and in fact cannot be separated from the business.

You had better hope that company is your own, and not your competitor.