“One of the things that a digital world allows you to do is run your companies in completely different ways.” | ||

| --Jeffrey R. Immelt, Chairman and CEO, GE | ||

How an organization is structured—its roles, processes, and coordination mechanisms—can make or break an organization’s ability to achieve effective BTM.[1] Peter Weill and Jeanne Ross[2] found that even when firms had similar business strategies, those with well-designed structures reaped at least 20 percent greater returns compared to those with poorly designed structures.

This chapter discusses the logic for creating and evolving organizational structures and examines the organizational models that maximize a company’s potential to achieve BTM capabilities. The importance of change management and communication in creating an ideal organization is discussed, and the use of a modular organizing logic in creating the best environment for BTM is explained.

In Brief

Three trends influence organizing for BTM: the need for rapid and innovative use of technology, supply-side pressure to deliver reliable and low-cost services, and new compliance requirements.

Changing business conditions cause alterations to business models and processes. Changing conditions in technology demand also impact how the business should be organized and managed.

It is critical that business and technology stay connected and coordinated. Therefore, BTM capabilities[3] such as Organization Design and Change Management become essential.

A company’s organizing logic should emphasize relationship networks for visioning, innovation, and sourcing, and it should explicitly manage three categories of value-creating processes.

Firms should adopt a modular organizing logic because it facilitates an efficient and adaptive approach to achieving BTM capabilities.

Three significant forces influence how business technology executives think about organization structures for managing business technology[4] today:

Demand-side forces result in the need for rapid, innovative, safe, and cost-effective use of business technology. With technology increasingly embedded into products, services, business processes, and relationships, firms must nurture creative and innovative uses of it. A firm must also encourage initiatives for business technology-based competitive maneuvering, productivity, and cost leverage. Managing these demands requires the blending of business and technology knowledge. When only business executives possess insights about business opportunities and needs, and only technology executives are savvy about how information technologies might support or shape business opportunities, the situation is neither optimal nor sustainable. Instead, demand pressures require organizational structures that facilitate collaboration among business and technology executives so that they can innovate and experiment.

Supply-side forces require delivery of reliable and cost effective business technology. With the horizontal fragmentation of the IT industry and the viability of outsourcing and offshoring options, it is hard to find a firm that doesn’t cite “solutions integration” as a major path to added value. That means managing relationships with a diverse number of service providers. It also means rapid delivery of applications by fast-cycle projects, and maintaining a workforce with crucial competencies in the face of rapid obsolescence of business technology skills. Well-designed organizational structures can deliver effective management of external partnerships and human capital.

Administrative forces result in the need for better management of business technology. Almost everywhere today, IT assets[5] are a significant proportion of the capital base, and many recent reports have pegged the proportion of this relative to overall capital investments at levels that exceed 50 percent of the total. This fact carries a range of administrative imperatives: greater oversight and management of business technology productivity and risk; appropriate controls and audits as an integral element of enterprise risk management; and continual benchmarking of business technology costs, with transparent costing models for services. Organizational models must explicitly enable the financial management and control of business technology. Similarly, strategic planning for business technology must direct attention toward the timing of investments, anticipating emerging business needs, and developing appropriate infrastructure and services-provisioning capabilities. Organizational models must ensure that this strategic planning is actually carried out with results executed, rather than sitting on a shelf.

When designing an appropriate organizational structure for managing business technology, a firm should consider the following five principles:

Chapter 1,“What Is BTM?,” discussed the states of alignment, synchronization, and convergence of business and technology management. Key to this discussion was the notion that an organization may operate in one or more of these states simultaneously, and this has significant organizational design ramifications. An organization operating in the state of alignment will find that its organization design must be appropriate for an environment where technology supports, enables, and does not constrain the company’s current and evolving business strategies. Operating at a state of synchronization means that sufficient organizational flexibility must exist to allow for business technology that not only enables the execution of current business strategy but also anticipates and shapes future business options. Ultimately, the state of convergence means that an organization’s business and technology leaders are able to operate simultaneously in both spaces, and that these areas have merged in both strategic and tactical senses, which brings an entirely different perspective to the design of the organization.

Given that these three states may even occur simultaneously within different sections of an organization, design efforts must consider the current and expected future state of the organization with respect to alignment, synchronization and convergence. These efforts must deliver the right level of coupling between business management and technology management strategies, processes, and activities based on the current operating environment (see Figure 5.1).

Managing business and technology together maximizes the contributions of each.

Figure 5.1. Coordinating Business and Technology

Organization design efforts can reflect the current state of an organization and deliver the needed levels of coordination in many ways. For example, in the case of the state of synchronization, organization design should emphasize this organizational vision and related goals about the role of business technology. Therefore, the organization design should encourage business innovation, strategic experiments, and risk-taking with business technology. For organizations operating nearer to convergence, implementing organizational units to catalyze joint attention to business and technology initiatives for innovation and productivity enhancement is an appropriate outcome. One example of such a unit is the corporate Business Technology Council (referred to as the IT Executive Council in many firms). The members of this council include the CEO, CFO, CIO, and other senior business executives. This council promotes organizational awareness of the role of business technology and monitors major enterprise initiatives.

In seeking the right level of coordination, an organization design must weigh the extent to which its business strategy and strategic initiatives help set the priorities for business technology, including investments in infrastructure and services, application portfolios, and sourcing relationships. At the same time, this design must account for the fact that business technology is increasingly shaping future business strategies, processes, and initiatives. For example, with greater data mining and warehousing capabilities in the infrastructure, business strategy could evolve toward greater personalization and customer intimacy, and result in the differentiation of the organization’s product or service offerings.

In supporting these kinds of options, an organizational structure must facilitate true coordination. It must assist firms in exploiting technology-enabled opportunities such as virtual integration, direct access to customers, and cross-divisional or business-unit integration. For example, at Cisco Systems, the executive management team considered customer advocacy and relationships to be the strategic drivers of its business model. Cisco management focused on the coordination of business technology and customer-centric capabilities by having the CIO report to the senior executive responsible for customer advocacy, and by linking business and technology executives’ compensation to customer-centric innovation using business technology.

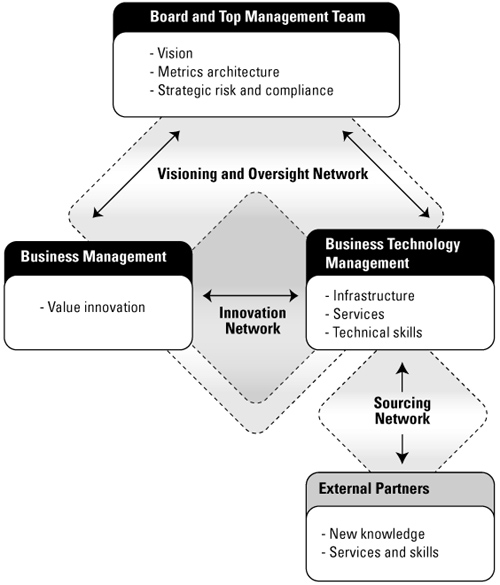

Chapter 4, “Governance: Who’s in Charge?,” introduced a networked governance model for business technology management (see Figure 5.2). This model emphasizes that four categories of stakeholders are important: the board and the top management team, business management, technology management, and external vendors. Among these stakeholders, three kinds of relationship networks are important: visioning, innovation, and sourcing.

A networked governance model includes a visioning and oversight network, an innovation network, and a sourcing network.

Figure 5.2. A Networked Governance Model

Visioning networks involve senior business and technology executives and the board. They foster collaboration for creating and articulating a strategic vision about the role and value of business technology. Visioning networks help top management teams describe their perspectives on the role of business technology, their strategic priorities for its use, and the links they see between it and drivers of the business strategy. One of the mechanisms for establishing a visioning network is to have the CIO as a formal member of the top management team. Other mechanisms include the establishment of a Business Technology Management Council and a Business Technology Investment Board.

Innovation networks involve business and technology executives. They foster collaboration for conceptualizing and implementing business technology applications. These applications are often aimed at enhancing the firm’s agility and innovation in customer relationships, manufacturing, product development, supply chain management, or enterprise control and governance systems. An example of organizational mechanisms that promote innovation networks is a corporate and divisional project approval committee. Whereas visioning networks engage the board and the top management to shape overall enterprise perspectives about the strategic role and value of business technology, innovation networks focus on specific innovations and strategic applications.

Sourcing networks are relationship networks between business technology executives and external partners. Their purpose is to foster collaboration between these internal and external parties when they are negotiating and managing multi-sourcing arrangements, joint ventures, or strategic alliances. Sourcing networks can help companies not only lower their costs but also augment their capabilities and business thinking about innovative uses of business technology. Attention to sourcing networks must be emphasized in key organizational units that deal with the technical architecture and infrastructure (for example, Office of Architecture and Standards) and the management of technology investments (Enterprise Program Management Office [EPMO]).

Successful implementation of BTM capabilities requires not only the design of effective organizational structures, but attention to three categories of processes: foundation, primary, and secondary (see Table 5.1).

Table 5.1. Three Categories of Processes

Foundation processes are aimed at managing supply side pressures and relate to the two fundamental competencies of infrastructure and human capital.

Primary processes are aimed at managing demand pressures and relate to the delivery and support of business capabilities through enabling business technology and services. The three primary processes are

Value innovation. —Conceptualizing strategic business technology needs and opportunities in the form of applications

Solutions delivery. —Building business technology applications

Services provisioning. —Providing help desk, desktop configuration, and other support services

These primary processes are the touch points through which business clients perceive the quality, contributions, and effectiveness of business technology.

Secondary processes are related to administrative needs and requirements. Their contribution is measured by how well they support and enable the foundation and primary processes. The two secondary processes are strategic planning and financial management.

Experience and research have revealed a number of modular organizational units that should be the building blocks of contemporary organization designs (see Table 5.2).

Table 5.2. Modular Organizational Units

The effectiveness of these modular organizational units in nurturing visioning and oversight networks, innovation networks, sourcing networks, and in supporting foundation, primary, and secondary processes varies. Specific modular organizational units have different levels of relevance and impact depending on the type of governance network or value creating process (see Tables 5.3 and 5.4).

Table 5.3. Modular Organizational Units and Governance Network Types

Table 5.4. Modular Organizational Units and Value-Creating Process Types

Business technology executives must understand how these organizational units should be configured into an overall organizational model for the firm. Also, as business conditions change they must determine the best way of adjusting and improvising specific governance networks or BTM processes. This must be accomplished without disrupting the organization or other networks and processes. The modular organizing logic described in Tables 5.2, 5.3, and 5.4 best accomplishes these tasks. Using a modular approach, firms choose specific organizational units to address each of the governance networks and to steward process categories (see Table 5.1). Depending on the industry and organizational conditions at any time, specific units might be more appropriate for each network and process. The advantage of the modular logic is that it allows the implementation and adaptation of organizational units for each important governance network and value-creating process. Traditionally, firms have designed their organizational structures using a monolithic organizing logic, by choosing either centralization or decentralization of BTM decisions. However, today’s organizing logic requires a much more sophisticated perspective that blends the virtues of centralization and decentralization.[6] The modular logic allows firms to unbundle their implementation of organizational units for different BTM activities.

Building and managing a network of relationships with vendors, systems integrators, third-party applications developers, and business process outsourcing providers is critical. There are at least three reasons why such an extended network is necessary. First, external partners can be used to augment existing proficiencies (for example, solutions delivery, global infrastructure services) in addition to lowering the costs of global services provisioning. Second, external partners can be used to augment existing business capabilities (for example, online selling or procurement through third-party hosted Web sites) or lower the costs of execution of business processes (for example, call center outsourcing, benefits management). Finally, external partnerships can be leveraged in building new business capabilities, responding to new threats, vulnerabilities, or regulatory demands (for example, SOX attestations and compliance), and conducting strategic business experiments (for example, building business capabilities around RFID technologies).

Sourcing decisions permeate many of the value-creating processes for business technology management. For instance, infrastructure management processes should include leasing of IT assets (for example, desktops), licensing of software, and outsourcing (for example, data centers, network management). Similarly, with the growing sophistication of outsourcing and offshore firms, solutions delivery processes include extensive partnering with external firms. As a final example, with the growing tide of interest in enterprise risk management, external auditing firms should become partners in technology risk management and audit.

The following questions should frame decisions about outsourcing and partnering:

What are the core activities of the organization? What activities can be regarded as core—strategic in nature and best managed internally? For example, the development and maintenance of architecture and standards is a core activity and must be managed through the Office of Architecture and Standards. “Context” activities are important but not strategic and can be managed through outsourcing. For example, the procurement and maintenance of desktops, network services, and helpdesk services are appropriately viewed as “context.”

What are the comparative capabilities of the external partners? Outsourcing makes sense when external partners possess economies of scale for specific activities (for example, customer call centers, benefits administration) or possess expertise not readily available inside the firm (for example, IT audits or risk assessment).

What are the appropriate monitoring, oversight, and relationship management practices? Service level agreements have traditionally been used to manage outsourcing relationships. Such agreements are appropriate for arm’s-length relationships governed through fixed contracts. However, with growth in a number of ongoing and collaborative partnerships with external partners, where the firm engineers shared processes and knowledge with its partners, there is a need for other forms of monitoring and relationship management practices. The creation of a specific role for Partner Relationship Management (PRM) is important. In addition, the establishment of processes for intellectual capital management will be critical. Finally, due diligence processes must be established to monitor the ongoing viability of the business partners and their potential impacts on business and risks.

Traditional wisdom about organization structures has primarily focused on governance rights for key decisions. Most attention had been on three designs: centralized, decentralized, or federal. In the centralized designs, most decisions are made by the IT function. In the decentralized, most key decisions are made by business. The federal design combines elements of both by dispersing authority for specific decisions to the business units and the IT function. However, as should be evident from the principles described previously, a more sophisticated logic is needed today.

| 1. | See the “Key Terminology” section in Chapter 1. |

| 2. | Peter Weill and Jeanne Ross. IT Governance: How Top Performers Manage IT Decision Rights for Superior Results. Harvard Business School Press, 2004. |

| 3. | See the “Key Terminology” section in Chapter 1. |

| 4. | Ibid. |

| 5. | Ibid. |

| 6. | Agarwal, R. and Sambamurthy, V. Principles and Models for Organizing the IT Function. 2002. |