2

TRUST

On a Friday afternoon in the spring of 2017, Travis Kalanick, then CEO of Uber, walked into a conference room at the company’s minimalist Bay Area headquarters. A wildly talented deputy, Meghan Joyce, general manager for the United States and Canada, had orchestrated the meeting. Joyce was convinced that we could be helpful, but that was not our starting point. From everything we’d read about the iconic, ride-hailing startup, it looked like a company with little hope of redemption.a

First, some context: Uber had disrupted at least one industry, but its astonishing success seemed to come at the price of basic decency. A #deleteUber campaign began shortly after the company appeared to take advantage of a taxi strike in response to President Trump’s travel ban. A few months later, Uber engineer Susan Fowler blogged about her experience of harassment and discrimination in a culture she convincingly portrayed as ruthless.1 Footage then emerged of Kalanick interacting with an Uber driver, where he appeared dismissive of the difficulties of earning a living in a post-Uber world. Other charges leveled at the company in this period reinforced Uber’s reputation as a cold-blooded operator that would do almost anything to win.

It did not help the company’s position that some of its challenges had morphed into public reckonings with ills that plagued the rest of the tech sector, too.2 These included inertia and confusion when it came to building safe and healthy workplaces. Companies that had no problem achieving the impossible commercially seemed overwhelmed by how to create conditions in which a large, diverse workforce could thrive.

As Frances waited for Kalanick to make his entrance, she braced herself for the smug CEO she had read about. That person wasn’t the one who walked in. Kalanick arrived humbled and introspective. He had thought a lot about how some of the cultural values he’d instilled in the company—the very values that had fueled Uber’s success—had also been misused and distorted on his watch. He revealed deep respect for what his team had achieved, but he also recognized that some of the people he had placed in leadership roles lacked the training, mentorship, or breathing room to be effective.

Whatever mistakes Kalanick had made up to this point, here was a leader trying to do the right thing. He and Frances took fast turns at a whiteboard, sketching out possibilities for the company. By the time Arianna Huffington, the sole woman on Uber’s board at the time, came in to offer her perspective, Frances was open to the idea that we could be useful. Huffington was just coming from a heated session with female employees, and you could tell she had absorbed a lot of pain. The scene was the opposite of what we had come to expect from hands-off, Silicon Valley boards. Huffington was in the trenches with Kalanick, and her sleeves-up commitment moved us.

Retreating back to our home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, we debated whether to take on the project. There were lots of reasons to stay away from it. The work would be hard and its outcome uncertain, to say nothing of the brutal commute. There were real problems to solve, including a frustrated workforce and a brand heading toward toxic. But we realized that if we could do it here, if we could help get Uber back on the right path, then we could give license to countless others to restore humanity to organizations that had lost their way.

So where did we begin? We started with trust.3

The foundation of leadership

We think about trust as rare and precious, and yet it’s the basis for almost everything we do as civilized people. Trust is the reason we’re willing to exchange our hard-earned paychecks for goods and services, pledge our lives to another person in marriage, cast a ballot for someone who will represent our interests. We rely on laws and contracts as safety nets, but even those systems are ultimately built on trust in the institutions that enforce them. We don’t know that justice will be served if something goes wrong, but we have enough faith in the system to make deals with relative strangers. It’s not coincidental that trust ultimately found its way into the official US motto, “In God We Trust.” Even if trust in our earthly structures erodes, it’s so vital to the national project that we threw in a higher-order backstop.

As we previewed in chapter 1, trust is also the input that makes the leadership equation work. If leadership is about empowering others, in your presence and your absence, then trust is the emotional framework that allows that service to be freely exchanged. I’m willing to be led by you because I trust you. I’m willing to give up some of my cherished autonomy and put my well-being in your hands because I trust you. In turn, you’re willing to rely on me because you trust me. You trust that I will make decisions that advance our shared mission, even when you’re not in the room. The more trust that accumulates between us, the better this works.

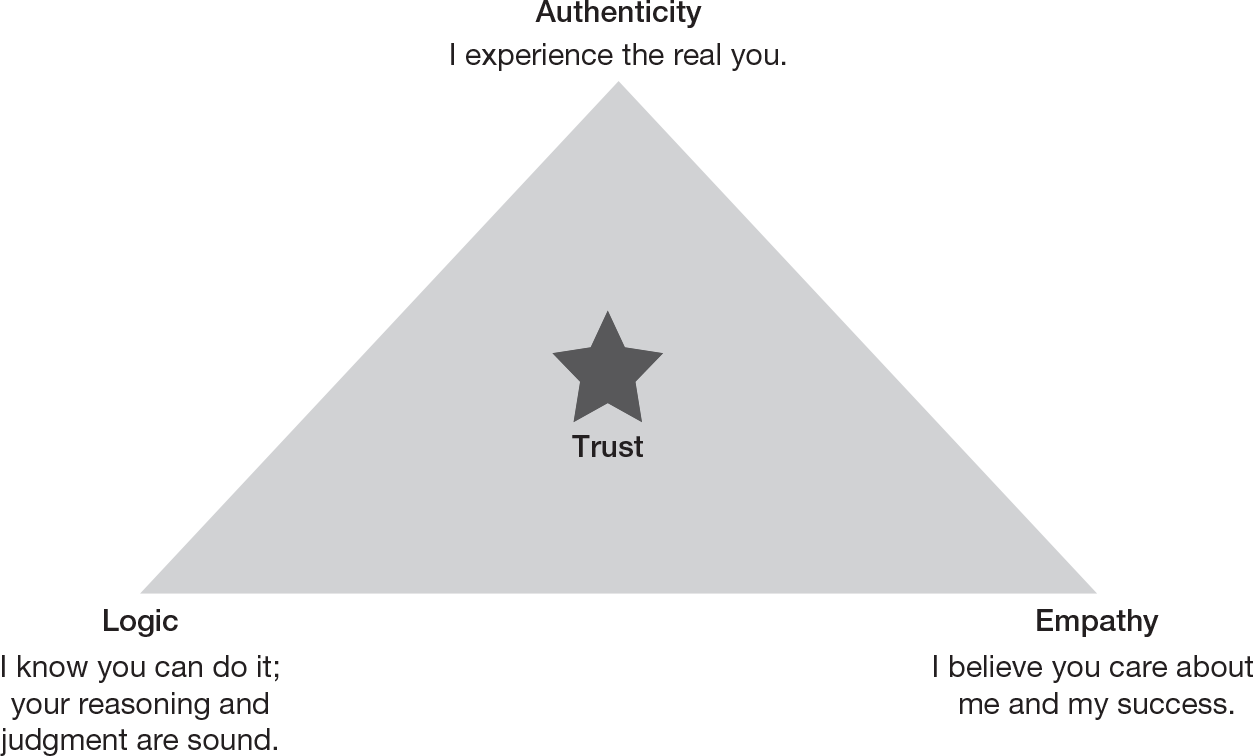

How do you build up stores of this essential leadership capital? Here’s the basic formula: people tend to trust you when they think they are interacting with the real you (authenticity), when they have faith in your judgment and competence (logic), and when they believe that you care about them (empathy). When trust is lost, it can almost always be traced back to a breakdown in one of these three drivers. You can find the roots of this framework in Aristotle’s writing on the elements of effective persuasion, where he argued that you need to ground your case in logos, pathos, and ethos. You will also find this pattern in much of modern psychology literature. (See figure 2-1.)

FIGURE 2-1

The trust triangle

Should we trust you?

What signals are you sending about whether the world should trust you? We don’t always realize what information (or more often, misinformation) we’re putting out there about our own trustworthiness. What’s worse, stress tends to amplify the problem. Under pressure, we often double down on behaviors that undermine trust. For example, we unconsciously mask our true selves in a job interview, even though it’s precisely the type of less than fully authentic behavior that’s going to reduce our chance of being hired.

The good news is that most of us generate a stable pattern of trust signals, which means a small change in behavior can go a long way. First, we tend to get in our own way, in the same way, over and over again. In moments when trust is broken (or fails to get any real traction), it’s usually the same driver—authenticity, empathy, or logic—that gets wobbly on us. In fact, we call this pattern of setbacks your trust “wobble.” Your wobble is the driver that’s most likely to get shaky in periods of low trust. Everyone, it turns out, has a wobble.

We also all have a driver where we’re rock solid, one that stays strong and steady in our interactions with others, regardless of the circumstances. One of the three trust drivers rarely lets us down, even if we’re woken up out of a dead sleep at 3:00 a.m. and asked to perform. We call this pattern your trust “anchor.” Your anchor is the attribute that’s least likely to get wobbly on you, even when the proverbial clouds start to gather and winds start to howl.

Your own trust diagnosis

Before getting started, we suggest identifying a compelling reason to do this work. If you could build more trust tomorrow than you did today, how would that impact your effectiveness as a leader? As usual, we suggest writing down the thoughts that come to mind.

Now think of a recent moment when you were not trusted as much as you wanted to be. Maybe you lost an important sale or didn’t get that stretch assignment. Maybe someone doubted your ability to execute or simply kept their distance from you on a project. Here’s the hard part: give this other person in the story—let’s call them your skeptic—the benefit of the doubt. Assume that their reservations were valid, and you were the one responsible for the breakdown in trust. This exercise only works if you own it.

If you had to choose from the short list of trust attributes, which of the three got in your way? From the skeptic’s perspective, which got wobbly on you? Did they think you might be putting your own interests first? Did the interaction feel all about you? That’s an empathy block. Did they question the rigor of your analysis or your ability to execute on an ambitious plan? That’s a logic problem. Or did they think you might be misrepresenting some part of your story, exaggerating the upside or downplaying the risks? That’s an authenticity issue.

Whichever it was, that’s your wobble, at least in this interaction. Draw a trust triangle and put a squiggly line under the unsteady attribute. If your wobble was empathy, for example, then your trust triangle would look like the one in figure 2-2.

Assuming your skeptic didn’t flee the room or laugh at the absurdity of your plan, something was also going right for you on the trust front. Which of the three trust pillars was unwavering? That’s your anchor in this story. Go back to your triangle and put a plus sign next to your anchor. If you chose logic as your anchor, for example, then your triangle should now look like the one in figure 2-3.

FIGURE 2-3

Which is your trust “anchor”?

Test your hypothesis

Our advice is to bring at least one other person along for your diagnostic ride. Sharing your analysis can be clarifying—even liberating—and will help you test and refine your hypothesis. Ideally, pick a thought partner who knows you well. About 20 percent of self-assessors need a round of revision, so choose a partner who can keep you honest if your analysis is off. Exchanging wobble stories with another person can also mediate any shame you may associate with losing trust. Wobbling is a universal human experience. What matters to your leadership mandate is what you choose to do about it.

For the advanced trust builders out there, consider going back and testing your analysis directly with your skeptic. This conversation alone can be an enormously powerful way to build and rebuild trust. Taking responsibility for a wobble reveals your humanity (authenticity) and analytic chops (logic), while communicating your commitment to the relationship (empathy).

Your challenge now is to look at your pattern of wobbles and anchors across multiple examples. Pick the top three or four interactions that stand out to you, for whatever reason, and do a quick trust diagnostic for each one. What do your typical wobbles and anchors seem to be? Does the pattern change under stress or with different kinds of stakeholders? For example, do you wobble in one way with your direct reports, but in a different way with people who have authority over you (this isn’t uncommon)?

Over the last decade, we’ve helped all kinds of leaders wrestle with trust issues, from seasoned politicians to millennial entrepreneurs to leaders of disruptive, multibillion-dollar companies (including Uber, which we’ll return to at the end of this chapter). When one retail CEO we advised identified his wobble, we watched him fix it in his next interaction. His challenge was empathy, and small changes in behavior—things like making eye contact, asking better questions, putting away his phone—had an immediate impact on his relationship with his team. In the next section, we offer some effective strategies for overcoming your own trust wobble, starting with the most common wobble we encounter among high-achieving leaders: empathy.

Empathy: Looking out for number one

Your wobble may be empathy if people often think you care more about yourself than about others. As we explored in chapter 1, this kind of signaling is a major barrier to empowerment leadership. If people think you’re primarily in it for you, then they’re far less willing to be led by you.

Empathy wobbles are common among people who are analytical and driven to learn. For many empathy wobblers, boredom is an enemy that must be taken down at all costs, in whatever corners of our daily lives it may be lurking. Long lines and slow traffic. Predictable TV storylines.b Meetings with colleagues who may need longer than we do to “get it.”

The tools and experience of modern leadership also make it increasingly difficult to communicate empathy, with twenty-four-hour demands on our time and multiple devices competing for our attention at any given moment. We also tend to have less time for recovery, which leads us to seek moments of micro-recovery throughout our day, sometimes smack in the middle of conversations with the very people we’re working to empower and lead. And all those open-office plans—now widely embraced for their practicality and design value—aren’t necessarily helping. There can sometimes be nowhere to pause and catch your breath in a truly communal workspace.4

We advise empathy wobblers to pay close attention to their behavior in group settings, particularly when other people have the floor. Consider the standard meeting example: an empathy wobbler’s engagement tends to be sky high at the kickoff of a meeting (you might learn something!) until the moment they understand the concepts and contribute their ideas. At this point, their engagement plummets and remains low until the gathering mercifully comes to an end. We call this dramatic arc the “agony of the super smart” (or ASS).

How do you signal you understand something before everyone else? Ah, well, the possibilities are endless. You could flamboyantly multitask, or find ways to look bored, or look down at your phone the first chance you get. Anything to make it clear that this meeting is beneath you. Unfortunately, the cost of these indulgences is trust. If you signal that you matter more than everyone else, then you can do many things, but being trusted as a leader isn’t one of them.

The prescription is easy to describe, but harder to execute: change your objective from getting what you need in the meeting to making sure everyone else gets what they need. In other words, take radical responsibility for everyone else in the room. Share the burden of moving the dialogue forward, even if it’s not your meeting. Search for the resonant examples that will bring the concepts to life, and don’t disengage until everyone in the room understands. Note that this is almost impossible to do as long as texting or checking email is an option, so put away your devices (everyone knows you’re not taking notes on their good ideas). See the graphic representation of this pivot in figure 2-4.5

The headline here is that the antidote to an empathy wobble is presence. What do the people around you need from you as a leader? What else could you be doing in this moment to empower them? It’s impossible to find out if your head is somewhere else, on your own needs and ambitions (and devices). The last thing we’ll say is this: if you do nothing else, put down your phone. You’ll be amazed at the immediate uptick in trust—and you may even get to end those meetings sooner. We’ve seen organizations that adopt high-empathy meeting norms cut the time they spend in meetings in half. (See the sidebar “Empathy and the Future of Work.”)

Empathy and the Future of Work

It has not been a banner decade for trust in the American workplace. We’ve grown increasingly skeptical that our employers will tell us the truth, have our backs in hard times, or compensate us fairly for the work we do. As massive forces such as globalization and technological innovation continue to reshape our experience of work, we’re pretty sure that someone else—or something else—will be doing our jobs in the future. We’re increasingly willing to believe, with good reason, that the game is rigged for an elite shareholder class that rarely has to follow the same rules we do.

If we look at this pattern through a trust lens, we would argue the US economy is dealing with a big, bad empathy wobble. Americans have become convinced that a growing number of companies are in it solely to enrich themselves, not to be of service to their customers (or, heaven forbid, their employees). This belief gets reinforced by everything from less-than-living wages to draconian noncompete agreements to the willful mishandling of our personal data.

Organizations that persuade us otherwise have a massive advantage. Iconic outdoor clothing retailer Patagonia has consistently prioritized social impact over financial returns, serving as a model for “not about you” leadership from its earliest days. Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard says he set out to build a company whose primary mission was to take care of customers, employees, and the planet.6 Patagonia now generates about $1 billion in sales each year, and has donated 1 percent of all revenue back to environmental nonprofits since 1985.

As trust in corporate America has eroded, Patagonia CEO Rose Marcario has doubled down on the company’s commitment to serve something bigger than its own success—and, in doing so, has quadrupled revenue during her tenure.7 She reinforces the company’s values by closing stores and offices so Patagonia employees can do more important things than sell clothes, like vote on election day. She also very visibly sued the US government in 2017 for misuse of public lands.8 To remove any doubt regarding Patagonia’s raison d’être, Marcario even changed the company’s mission statement from “Do no unnecessary harm” to “We’re in business to save our home planet.”9

We spoke with Marcela Escobari, who now leads the Workforce of the Future Initiative at the Brookings Institute, about how to rebuild trust at the scale of an economy. “Do we all need to Be Like Rose?” we asked. “Yes and no” was her answer. Before shifting her focus to the evolution of work, Escobari led USAID’s efforts to address issues of poverty, inequality, and citizen security in Latin America. She witnessed firsthand how trust was being destroyed in places like Venezuela—and also how it was being built and rebuilt in countries like Peru. In a world where mistrust is on the rise, her advice to business leaders is, yes, take the long view and make it about something more than your shareholders—channel your inner Rose Marcario—but also “never forget that investing in people has the possibility of infinite returns.”

Escobari argues that a higher-skilled and more resilient workforce may be the fastest path to a future where we trust each other again. Although there’s an obvious role for the public sector in driving this change, Escobari knows that the private sector is indispensable and is energized by a renewed corporate focus on retraining employees (rather than laying them off) as technology transforms the workplace. She cites many examples of companies effectively preparing their employees for a future of work that is not so far away, including companies like Costco, JetBlue, and Trader Joe’s. We’ve even seen companies at the scale of Walmart begin to invest in employee education in innovative ways. In 2018, Walmart made headlines with its “dollar-a-day” education benefit that gives associates the chance to earn a college degree through nonprofit partner universities, paying the equivalent of $1 a day as they progress toward a bachelor’s or associate’s degree.10

Our education bias is clear—see our histories and career choices—but we believe a big part of the remedy to America’s trust wobble is to increase fair access to opportunities to develop a competitive skill set. We need to level our winners-take-all playing field in a number of ways, starting with the chance to thrive in the workplace of the future. In this country’s founding documents, we promised to defend each other’s pursuit of happiness—not happiness itself, but the pursuit of it—as a sacred, inalienable right. Until we treat that promise with reverence again, we’re not going to solve our collective trust problem.

As one of our heroes, Brazilian thinker and teacher Paulo Freire, said, “What the educator does is make it possible for students to become themselves.”11 There is no higher human need than to realize our full potential, and no greater act of empathy than to enable that evolution in others. We believe the future of work—and of the planet Marcario has vowed to save—depends on our willingness to exchange the gift of each other’s transformation.

Logic: Large but not quite in charge

Your wobble may be logic if people don’t always have confidence in the rigor of your ideas—or full faith in your ability to deliver on them. The good news is the problem is typically rooted in the perception of wobbly logic rather than the reality of it. Either way, the effect is the same: if we’re not sure your judgment can handle the road ahead, then we’re less likely to want you at the wheel.

In the rare cases when wobbly logic is truly the problem, we advise going back to the data. Root the case you’re making in evidence, speak to the things you know to be true, and then (and this is the hard part) stop there. One reason Larry Bird was such an extraordinary basketball player was that he only took shots he knew he could reliably make. That choice made him different from so many other players, who often let ego and adrenaline cloud their shooting judgment. Bird studied and practiced so relentlessly that by the time the ball left his hands in the heat of competition, he knew exactly where it was going. If logic is your wobble, take Bird’s example and learn to “play within yourself.”

Once you get comfortable with how that feels, start expanding what you know. Along the way, don’t hesitate to learn from what other people know. Other people’s insights are among the most valuable—and overlooked—resources in the workplace, but accessing them requires a willingness to reveal you don’t have all the answers, something leaders often resist. We learned this lesson the hard way early in our careers, too often preferring to hide out and polish our own flawed logic rather than be vulnerable and ask for help. This choice cost us not only the opportunity to improve at a faster pace, but also the chance to build stronger relationships with our colleagues (asking for help can also reveal what energizes you professionally).

For most logic wobblers, however, rigor isn’t the issue. A more likely explanation for the breakdown in trust is that you’re not communicating your ideas effectively. There are generally two ways to communicate complex thoughts. The first way takes your audience on a journey, with twists and turns and context and dramatic tension, until they eventually get the payoff. Many of the world’s best storytellers use this technique. You can visualize this approach as an inverted triangle with an enchantingly circuitous route to the point. If logic is your wobble, however, this is a risky path. Without enough confidence in your narrative destination, the audience is tempted to abandon you along the way.

Try flipping the triangle. Start with your headline and then offer reinforcing evidence to back it up. This shift signals clarity of vision and full command of the facts. Everyone has a much better chance of following your logic, and even if you get interrupted along the way, you’ve at least had a chance to communicate your key idea. See Figure 2-5 for an illustration of this pivot.

FIGURE 2-5

Communication for logic wobblers

Flipping the triangle can immediately steady a logic wobble and reduce the likelihood of other workplace injustices, such as having your idea “stolen” in a meeting, just minutes after you’ve shared it. More often than not, our sticky-fingered colleagues are simply flipping the triangle for us.

Authenticity: Who was that masked man?

You may have an authenticity wobble if people feel they’re not getting access to the “real” you, to a full and complete accounting of what you know, think, and feel. If the version of reality you present feels overly curated or strategic, an invisible wall can form between you and the people around you.

A quick test: How different is your professional persona from the one that shows up around family and friends? If there’s a real difference, what are you getting in return for masking or minimizing certain parts of yourself? What’s the payoff (for example, approval or a sense of safety)? If you can easily answer these questions, then authenticity may be on your short list of challenges.

To be our “real selves” sounds nice in theory, but there can be powerful, hard-earned incentives to hold back certain truths. The calculation can be highly practical at times, if wrenching, as in the decision to stay closeted in a workplace that’s hostile to queer identities. There may also be times when expressing your authentic feelings may be ill-advised: women are disproportionately penalized for negative emotions in the workplace, and black men remain burdened by the false stereotype that they are predisposed to anger.12

We’re not talking about moments of prudent self-censorship, which sometimes can’t be divorced from a larger context of bias or low psychological safety.13 Instead, we’re talking about inauthenticity as a strategy for navigating the workplace. While this approach may help you solve short-term problems, it puts an artificial cap on trust and, by extension, your ability to lead. If we sense you’re withholding the truth or concealing your authentic self, if we don’t know what your genuine beliefs and values are, then we’re far less willing to make ourselves vulnerable to you in the ways that leadership demands.

Although this pattern can present in different ways, we’ve observed its cost up close in the performance of diverse teams. Diversity can be a tremendous asset in today’s marketplace, and the companies that get it right often build up powerful competitive headwinds. But, in our experience, this advantage isn’t automatic. Simply populating your team with diverse perspectives and experiences doesn’t always translate into better performance.14

In fact, the uncomfortable truth is that diverse teams can underperform homogenous teams if they’re not managed actively for differences among team members, due in part to a phenomenon called the common information effect.15 It works like this: As human beings, we tend to focus on the things we have in common with other people. We tend to seek out and affirm our shared knowledge, as it confirms our value and kinship with the group. In diverse teams, by definition, this limits the amount of information that’s readily available for collective decision making.

In figure 2-6, we illustrate this dynamic for two teams of three people, one team where the three teammates are different from each other and another where they’re similar. When difference is unmanaged, the common information effect gives the homogenous teams a natural advantage.

FIGURE 2-6

Available information for diverse and homogeneous teams

* The common information effect focuses a team on shared knowledge and limits access to unique information.

In other words, if both diverse and homogenous teams are managed in exactly the same way—if they simply follow the same best practices in group facilitation, for example—the homogenous team is likely to perform better. No amount of feedback or number of trust falls can overcome the strength of the common information effect.

But here’s the thing: the common information effect only holds when we’re willing to wobble on authenticity. When we choose to bring our unique selves to the table, the parts of ourselves that are actually different from other people, then diversity can create an unbeatable advantage by expanding the amount of information the team can access. Indeed, the world starts to look a lot more like figure 2-7, where an inclusive three-person team is likely to outperform (read truly dominate) the other two teams.

FIGURE 2-7

Available information for inclusive teams

* The common information effect focuses a team on shared knowledge and limits access to unique information.

This expansion relies on the courage of authenticity wobblers. Believe us when we say we know this is hard—and sometimes too much to ask. At every step of our careers, we’ve been tempted to dilute who we are in the world. Although we’re as white as they come, we’re two queer women with strong opinions and high ambition, for ourselves and other people. One of us is most comfortable in men’s clothing and shoes that ask for nothing in return. In certain contexts, these things make us different.

But if those of us who are different give in to the pressure to hold back our unique selves, then we suppress the most valuable parts of ourselves. Not only do we end up concealing the very thing the world needs most from us—our differences—but we also make it harder for people to trust us in leadership, continuing a flywheel of diminishment that keeps the status quo firmly in place. The smaller we choose to make ourselves, the less likely we are to take up the space required to lead.

Here’s the reason to care, even if you don’t identify as different: all of us pay the price of inauthentic interactions, and all of us have a better chance of thriving in inclusive environments where authenticity can flourish. Which means that gender bias is not just a woman’s problem. Systemic racism is not just an African-American or Latinx problem. It’s our shared moral and organizational imperative to create workplaces where the burdens of being different are shouldered by all of us.

We will talk a lot more about how to do this in chapter 4, but the punch line is that it’s not as hard as it may seem. Inclusion is an urgent, achievable goal that requires far less audacity than disrupting industries or growing complex organizations, things organizations do every day without fear and confusion shutting down progress. If we all take full responsibility for leading companies where diversity can thrive, and we all take full responsibility for showing up in them authentically, then our chances of building trust—and achieving true inclusion—start to look pretty good.

So wear whatever makes you feel fabulous. Pay less attention to what you think people want to hear and more attention to what you need to say to them. Reveal your full humanity to the world, regardless of what your critics say. And while you’re at it, take exquisite care of people who are different from you with confidence that their difference is the very thing that could unleash you. (See the sidebar “Risking Authenticity in the Digital Age.”)

Risking Authenticity in the Digital Age

Authenticity in leadership can be particularly hard when it feels as if everyone’s watching, an awareness that’s heightened by social media and an unforgiving internet. The response to putting yourself out there—to say nothing of making the inevitable missteps—can be swift and harsh. This environment creates a powerful incentive to wobble on authenticity and conceal the honest, vulnerable parts of ourselves.

We believe the cost of giving in—and hiding out—is too high. Without authenticity, you won’t be fully trusted. And without being fully trusted, you won’t be able to build a leadership platform that’s worthy of you and your potential for impact. Here’s our best advice for how to reveal who you are in an age when everyone’s a critic.

Take back control from your primate brain. The part of your brain that’s wired for survival does an excellent job of protecting you, but it shouldn’t always be calling the shots. For one thing, it’s highly unreliable at evaluating threats (no, your upcoming speech is not going to kill you, despite the high levels of adrenaline being pumped into your system). Your primate brain is also not playing the long game. It was designed to get you to the end of the day, not to the end of a leadership journey filled with meaning and impact. Buddhism has been wrestling with how to master this part of the mind for thousands of years, and the modern mindfulness movement has created a bridge to accessible tools and practices that can be enormously helpful. Our advice is to at least give them a fair look.16

Find your authenticity triggers. Figure out the people and things that tend to pull your full humanity to the surface. Is it your beloved spouse? Favorite sports team? Passion for Harry Potter trivia? Surround yourself with reminders of these things or—better yet—find ways to somehow bring them with you into spaces where an inauthentic version of you has a habit of showing up. In the not-so-distant past, Anne sometimes struggled with authenticity when pitching new investors, a scenario that often felt safer behind a two-dimensional mask. One thing that made a difference was to incorporate stories about our son into those conversations, as his experience inspired the company she was launching. This choice made it easier for Anne to show up as herself and be an effective messenger of the company’s vision.

Drop the script. Make sure you’re not emphasizing logic at the cost of authenticity. There is an obvious upside to leaders being informed and articulate, but when it comes to trust, we also crave access to the person behind the talking points. Find moments to keep it real with people and communicate your unscripted thoughts and ideas. Start with low-risk settings, if needed, such as intimate lunches or meetings with allies. Dial up the stakes as you get increasingly comfortable flexing your authenticity muscles.

Give us the “why.” What drives you to do what you do every day? What has called you to the practice of leadership? Many leaders keep these fundamental truths to themselves, sometimes simply out of habit, missing an opportunity to build trust by revealing what matters most to them. If you don’t answer these questions for your colleagues, then they’ll have no choice but to fill in the blanks themselves, right or wrong.

Learn in public. At some point, it became a false badge of honor to think something and never waiver from that thought. Give yourself the freedom to update your point of view based on new information or experiences. Do it out in the open and model what it looks like to have the courage to evolve. Not only will we get to experience a more authentic version of you—the human brain is constantly updating and refreshing—but you will also give the rest of us permission to learn and keep an open mind. A great thing about authenticity is that it’s crazy infectious.

Build a Team. Authenticity is not a solo sport. It should not be attempted alone in the private distortion chamber of our own minds. Build a Team (capital T) of friends and colleagues around you who can help you stay connected to the real you. Make it a requirement of Team membership that everyone is as comfortable with your insecurity as your audacity. Now spend time with the Team on a very regular basis, no less than monthly.17

Focus on unleashing other people. Finally, remember what you came to do as a leader: empower other people, in both your presence and your absence. The less your agenda is about you and your shortcomings, the more the authentic version of you can show up and get the real work of leadership done.

Getting back to Uber

What was Uber’s wobble? Uber was certainly wobbling when we arrived, and we’re on record for calling it “a hot mess” at the time.18 Let’s revisit the basic trust-related facts: on the empathy front, the company had improved the lives of an unthinkable number of consumers, but many of the concerns of key stakeholders remained unaddressed, including employees demanding a healthy workplace and drivers looking for more support in their pursuit of a decent living.19 When it came to logic, despite Uber’s trajectory of hypergrowth, there were still open questions about the long-term viability of the company’s business model.20 Although some of these questions were reasonable to ask any company at this stage, it was time to start answering them. It was also time to ensure that Uber’s management ranks had the skills to lead an organization of its expansive scale and scope.21 Finally, at the heart of its authenticity challenges, no one was completely sure they were getting the full story.22

Kalanick knew Uber had a trust problem.23 By the time he invited Frances to join the company as Uber’s first senior vice president for strategy and leadership, a number of initiatives were already underway to steady the company’s biggest wobbles. In response to learning about Fowler’s experience through her blog post, Kalanick brought in former US Attorney General Eric Holder to lead an internal investigation on harassment and discrimination, and work had begun to implement Holder’s sweeping recommendations.24 In addition, new driver-tipping functionality was about to be rolled out, which would go on to generate $600 million in additional driver compensation in the first year of its launch.25 New safety features were also in development to give drivers and riders new tools to protect themselves.26

Kalanick did not get the chance to see most of his trust-building initiatives to completion, at least not from the chief executive’s chair. In June of 2017, the board removed him as CEO while he was on bereavement leave for his mother’s sudden death.c Frances spent the rest of the summer working with the newly formed executive leadership team, which had been tasked to run the company during the search for new leadership. Dara Khosrowshahi began his CEO tenure in September, bringing with him a track record of effectiveness at the helm of young companies.

Frances immediately began working with Khosrowshahi to continue the campaign to rebuild trust internally. Together they led an effort to rewrite the company’s cultural values, one that invited input from all fifteen thousand employees on the commitments they wanted Uber to live by. A new motto they settled on was “We Do the Right Thing. Period.” Other early trust wins for Khosrowshahi included strengthening relationships with regulators and executing a logic-driven focus on the services and markets that were most defensible.27

Most of the work we did during this period was focused on rebuilding trust at the employee level.28 Some things were easy to identify and fix, like ratcheting down the widespread, empathy-pulverizing practice of texting during meetings about the other people in the meeting, a tech company norm that shocked us when we first experienced it. We introduced a new norm of turning off all personal technology and putting it away during meetings, which forced people to make eye contact with their colleagues again.

Other challenges were harder to tackle, like the need to up-skill thousands of managers. Our take was that Uber had underinvested in its people in a context of hypergrowth, leaving many managers underprepared for the increasing complexity of their jobs.29 We addressed this logic wobble with a massive influx of executive education using a virtual, interactive classroom, which allowed us to engage employees in live case discussions—our pedagogy of choice—whether they were in San Francisco, London, or Hyderabad. Although our pilot program was voluntary and sometimes scheduled at absurdly inconvenient times in some time zones (middle of the night), six thousand Uber employees based in more than fifty countries participated in twenty-four hours of classes over sixty days. It was an extraordinary pace, scale, and absorption of management education.

The curriculum gave people tools and concepts to develop quickly as leaders—and, yes, to build more trust—while flipping a whole lot of upside-down communication triangles. Employees gained the skills not only to listen better, but also to talk in ways that made it easier to collaborate across business units and geographies. Frances also visited key global offices in her first thirty days on the job, carving out protected spaces to listen to employees and communicate leadership’s commitment to build a company worthy of its people. At a time when many employees were conflicted about their Uber affiliations, Frances committed to wearing an Uber T-shirt every day until the entire company was proud to be on the payroll. (Evenings and weekends were not excluded, creating a number of awkward family moments for us, including a black-tie event.)

By the time Frances moved on from her full-time role, Uber was less wobbly.30 There were still problems to be solved, but indicators such as employee sentiment and brand health were heading in the right direction, and the march toward an IPO began in earnest.31 Good people were deciding to stay with the company, more good people were joining, and in what had become our favorite indicator of progress, an increasing number of Uber T-shirts could now be spotted on city streets. It was all a testament to the talent, creativity, and commitment to learning at every level of the organization—and to the foundation of trust that first Kalanick and then Khosrowshahi had been able to rebuild.

Trusting yourself

We’ll talk more about Uber in the chapters ahead, particularly in chapter 6, but here’s where we’ll leave you in this part of the discussion: How much do you trust yourself? Trust is the starting point for leading others, but the path to leadership begins even earlier, with your willingness to empower yourself. What are the wobbles in that most intimate of relationships?

For example, you may not be taking care of yourself with enough empathy and compassion. As we explored in chapter 1, until you can reliably meet your own needs, you won’t have the strength to be an effective leader and unleash anyone else. Conversely, you may lack conviction in your own logic and ability to perform. Finally, are you being honest with yourself about your true ambitions? Or are you hiding what really excites and inspires you behind whomever the world wants you to be? If the answer is yes or even “maybe,” then you may have found the source of your authenticity block.

Our point is that it’s not uncommon for the wobbles and anchors we experience with other people to map back to the way we feel about ourselves. Which is another reason to do this work: If you don’t fully trust yourself, why should the rest of us? Once you answer that question and stabilize your trust wobbles—with both yourself and others—you get to move onto love, the next ring of empowerment leadership and the focus of chapter 3. There we’ll explore how to create the conditions in which other people can reliably excel.

GUT CHECK

Questions for Reflection

- How would it impact your leadership to build more trust tomorrow than you did today?

- In moments when trust has broken down or failed to gain traction, which of the core drivers of trust tend to get wobbly on you: empathy, logic, or authenticity?

- How do stress and pressure impact your ability to build trust with others? Does your wobble change or get even wobblier?

- Do you lead an organization or team that needs to rebuild trust with its key stakeholders? If so, what is the institutional wobble that needs to be addressed?

- How will you turn your trust diagnostics into meaningful action? What can you start doing immediately to build more trust with the people around you?