Chapter 12

Local Solutions to Reduce Inequities in Health and Safety

Reprinted with permission from the National Academy of Sciences, Courtesy of the National Academies Press, Washington DC. The responsibility for the content of this chapter rests with the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the Institute of Medicine or its committees and convening bodies.

Learning Objectives

- Understand the importance of addressing the underlying determinants of health inequities

- Articulate the necessity of employing both health care and community-focused strategies to prevent inequities in health and safety

- Identify how health inequities are systematically created and delineate elements of an effective strategy within health care and at the community level to reduce inequities in health and safety

Equitable Health: A Four-Pronged Solution

In Alameda County, California, where the authors live and work, an African American child born in Oakland's flatlands will live an average of fifteen years less than a white child born in the Oakland hills neighborhood (Alameda County Public Health Department, 2008). Further, for every $12,500 in income difference between families, people in the lower-income family can expect to die a year sooner. Tragically, public health data confirms this same jarring reality all across American cities, suburbs, and rural areas.

Good health is precious. It enables people to enjoy their lives and focus on what is important to them—their families, friends, and communities. It fosters productivity and learning, and it allows people to capitalize on opportunities. However, good health is not experienced evenly across society: heart disease, cancer, diabetes, stroke, injury, and violence occur in higher frequency, earlier, and with greater severity among low-income people and communities of color—especially African Americans, Native Americans, Native Hawaiians, certain Asian groups, and Latinos (Smedley, Stith, and Nelson, 2003). For example:

- Compared to whites, American Indians and Alaska Natives are 2.3 times more likely to have diagnosed diabetes, African Americans are 2.2 times more likely, and Latinos are 1.6 times more likely (CDC, 2007).

- Among African Americans between the ages of ten and twenty-four, homicide is the leading cause of death. In the same age range, homicide is the second leading cause of death for Hispanics, and the third leading cause of death for American Indians, Alaska Natives, and Asian/Pacific Islanders (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2006). Homicide rates among non-Hispanic, African American males ten to twenty-four years of age (58.3 per 100,000) exceed those of Hispanic males (20.9 per 100,000) and non-Hispanic, white males in the same age group (3.3 per 100,000) (CDC, 2008e).

- Native Americans have a motor vehicle death rate that is more than 1.5 times greater than whites, Latinos, Asian/Pacific Islanders, and African Americans (CDC, 2006; U.S. Department of Transportation, 2006).

- Poverty is associated with risk factors for chronic health conditions, and low-income adults report multiple serious health conditions more often than those with higher incomes (National Center for Health Statistics, 2007).

- The average annual incidence of end-stage kidney disease in minority zip codes is nearly twice as high as in nonminority zip codes (National Minority Health Month Foundation [NMHMF], 2007).

- Premature death rates from cardiovascular disease (i.e., between the ages of 5 and 64) are substantially higher in minority zip codes than in nonminority zip codes (NMHMF, 2007).

- Education correlates strongly with health. Among adults over age twenty-five, 5.8 percent of college graduates, 11 percent of those with some college, 13.9 percent of high school graduates, and 25.7 percent of those with less than a high school education report being in poor or fair health (CDC, 2005b).

Health inequity is related both to a legacy of overt discriminatory actions on the part of government and the larger society, as well as to present day practices and policies of public and private institutions that continue to perpetuate a system of diminished opportunity for certain populations. Poverty, racism, and lack of educational and economic opportunities are among the fundamental determinants of health or alternatively poor health, lack of safety, and health inequities, contributing to chronic stress and building upon one another to create a weathering effect, whereby health greatly reflects cumulative experience rather than chronological age (Geronimus, 2001). Further, continued exposure to racism and discrimination may in and of itself exert a great toll on both physical and mental health (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1999). Inequities in the distribution of a core set of health-protective resources also perpetuate patterns of poor health.

Historically, African Americans, Native Americans, Alaska Natives, and Native Hawaiians, in particular, have to varying extents had their culture, traditions, and land forcibly taken from them. It is not a mere coincidence that these populations suffer from the most profound health disparities and shortened life expectancies. In many of the low-income and racially segregated places where health disparities abound, a collective sense of hopelessness is pervasive, and social isolation is rampant. This individual- and community-level despair fuels chronic stress, encourages short-term decision making, and increases the inclination toward immediate gratification, which may include tobacco use, substance abuse, poor diet, and physical inactivity.

To date, the collective national response has focused on what happens after people get sick or injured. Improving the health care system by increasing access and quality remains an integral component of addressing health inequities. At the same time, recent data indicates we must do more. Despite a decade-long investment in launching clinically focused initiatives to reduce health disparities, the United States has made virtually no significant progress in this domain (Voelker, 2008; House and Williams, 2000).

The National Institutes of Health defines health disparities as “diseases, disorders, and conditions that disproportionately afflict individuals who are members of racial and ethnic minority groups” (National Institutes of Health, 2002, p. 7). Health inequities are “differences in health which are not only unnecessary and avoidable but, in addition, are considered unfair and unjust” (Whitehead, 1990, p. 5). Thus, equity and inequity are based on core American values of fairness and justice whereas disparity is a narrow descriptive term that refers to measurable differences but does not imply whether this disparity arises from an unjust root cause. For the purposes of this chapter, the term inequity is used when the referenced differences in health outcomes have been produced by historic and systemic social injustices, or the unintended or indirect consequences of social policies.

Health equity is everyone's issue, and finding solutions will significantly benefit everyone. As the United States population becomes increasingly diverse, achieving a healthy, productive nation will depend even more on keeping all Americans healthy. An equitable system can drastically lower the cost of health care for all, increase productivity, and reduce the spread of infectious diseases, thus improving everyone's well-being. Last—and most importantly—the idea of equity is based on core American values of fairness and justice. Everyone deserves an equal opportunity to prosper and achieve his or her full potential, and it is our moral imperative to accomplish this.

We can remedy the problem of inequities in health and safety outcomes by creating a new paradigm addressing the needs that are critical to achieving health equity, and the specific challenges that affect integrating solutions into practice and policy. The first need is for a coherent, sustainable health care system that adequately meets the requirements of the entire U.S. population and of racial and ethnic minorities in particular. The second need is for adequate community prevention strategies that target the factors underpinning why people get sick and injured in the first place. These should be integrated to form a unified system for achieving health, safety, and health equity in the United States.

In this chapter, we propose a set of solutions that are achievable within the local arena. By local, we mean state, regional, and community levels. These solutions not only address the critical needs but also bridge traditional health promotion, disease management, and health care solutions with more upstream work that focuses on preventing illness and injury in the first place. We will outline a composite of community and health care factors that affect health, safety, and mental health and that—most importantly—provide the framework for accomplishing a four-pronged solution:

1. Strengthen communities where people live, work, play, socialize, and learn.

2. Enhance opportunities within underserved communities to access high-quality, culturally competent health care with an emphasis on community-oriented and preventive services.

3. Strengthen the infrastructure of our health system to reduce inequities and enhance the contributions from public health and health care systems.

4. Support local efforts through leadership, overarching policies, and through local, state, and national strategy.

Policy and institutional practices are the key levers for change. Institutional practices along with public and private policy helped create the inequitable conditions and outcomes confronting us today. Consequently, we need to focus on these areas—in community, business/labor, and government—in order to “unmake” inequitable neighborhood conditions and improve health and safety outcomes. Policies and institutional/organizational practices significantly influence the well-being of the community; they affect equitable distribution of its services; and they help shape norms, which, in turn, influence behavior.

The following policy principles, adapted from Life and Death from Unnatural Causes: Health and Social Inequity in Alameda County (Alameda County Public Health Department, 2008), provide guidance for taking on the challenge of addressing health inequities:

- Understanding and accounting for the historical forces that have left a legacy of racism and segregation is key to moving forward with the structural changes needed. A component of addressing these historical forces should consider policy and reform related to immigrant groups—notably Latinos, Asians, and Arab Americans.

- Acknowledging the cumulative impact of stressful experiences and environments is crucial. For some families, poverty lasts a lifetime and is perpetuated to next generations, leaving its family members with few opportunities to make healthful decisions.

- Meaningful public participation is needed with attention to outreach, follow-through, language, inclusion, and cultural understanding. Government and private funding agencies should actively support efforts to build resident capacity to engage.

- Because of the cumulative impact of multiple stressors, our overall approach should shift toward changing community conditions and away from blaming individuals or groups for their disadvantaged status.

- The social fabric of neighborhoods needs to be strengthened. Residents need to be connected and supported and feel that they hold power to improve the safety and well-being of their families. All residents need to have a sense of belonging, dignity, and hope.

- While low-income people and people of color face age-old survival issues, equity solutions can and should simultaneously respond to the global economy, climate change, and U.S. foreign policy.

- The developmental needs and transitions of all age groups should be addressed. While infants, children, youth, adults, and elderly require age-appropriate strategies, the largest investments should be in early life because important foundations of adult health are laid in early childhood.

- Working across multiple sectors of government and society is key to making the necessary structural changes. Such work should be in partnership with community advocacy groups that continue to pursue a more equitable society.

- Measuring and monitoring the impact of social policy on health to ensure gains in equity is essential. This will include instituting systems to track governmental spending by neighborhood, and tracking changes in measurements of health equity over time and place to help identify the impact of adverse policies and practices.

- Groups that are the most impacted by inequities must have a voice in identifying policies that will make a difference as well as in holding government accountable for implementing these policies.

- Eliminating inequities is a huge opportunity to invest in community. Inequity among us is not acceptable, and we all stand to gain by eliminating it.

Critical Needs for Achieving Equitable Health in the United States: A Health System

We need a coherent, sustainable health care system that adequately meets the health requirements of the entire U.S. population and of racial and ethnic minorities in particular. When we talk about fixing the health care system in the United States, we assume there is a system that can be improved. The underlying problem, however, is that we have no coherent system in the first place. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) does take some important steps including expanding access and funding that reflects an awareness of the value of a comprehensive approach to health. Notably, the ACA's establishment of the Prevention and Public Health Fund and the development of a surgeon-general-led National Prevention Strategy all point to an increased understanding of and commitment to prevention in the first place. However, additional steps and policies will be necessary in order to arrive at a fundamentally new approach to health that addresses inequities by bridging exemplary services available to all with a focus on the factors that have the greatest influence on health. The last time the World Health Organization published data on international health rankings in their World Health Report 2000—Health Systems: Improving Performance, the United States ranked number one in health expenditure per capita but only ranked thirty-seventh in overall health system performance (World Health Report, 2000). Among industrialized countries, the United States came in twenty-fifth out of thirty on infant mortality and twenty-third out of thirty on life expectancy (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2007). Even for those with adequate access to health care, the system is flawed. For example, there are huge inconsistencies in the delivery of recommended care across a wide range of conditions and population groups (Davis, Taira, and Chung, 2006); medical errors are estimated to result in approximately ninety-eight thousand unnecessary deaths and over one million excess injuries each year (CDC, 2005a; Institute of Medicine [IOM], 2000a); medical practitioners' job dissatisfaction rates are growing; and major shortages in nursing and allied health professions are projected (American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 2009).

In a time of financial crisis, we may focus exclusively on reforming the areas of greatest expense in the economy, narrowing in on the cost of specific items as we try to reduce that cost or at least slow its increase. Studies have revealed that the dramatic rise in the prevalence of chronic disease is a major factor responsible for growth in U.S. health care spending (Thorpe, 2006). This is a cost that can be reduced through prevention (Trust for America's Health [TFAH], Prevention Institute [PI], The Urban Institute [UI], and New York Academy of Medicine [NYAM], 2008). An economic analysis revealed that investing even the modest amount of ten dollars per person in community-level initiatives aimed at reducing tobacco consumption, improving nutrition, and increasing physical activity results in a return on investment within two years and an estimated annual savings of over $15 billion nationally within five years (TFAH, PI, UI, and NYAM). Each year thereafter, the five-to-one return on investment is projected to increase. The savings from an investment in prevention in disenfranchised communities should be even greater because they experience the greatest burden of ill health. In addition to this chronic disease analysis, studies reveal that other health-related investments also yield a significant return. For instance, one dollar invested in breastfeeding support by employers results in three dollars in reduced absenteeism and health care costs for mothers and babies and improved productivity (United States Breastfeeding Committee, 2002); one dollar invested in lead abatement in public housing returns two dollars in reduced medical and special education costs and increased productivity (Brown, 2002); and one dollar invested in workplace safety measures returns four to six dollars in reduced illnesses, injuries, and fatalities (Occupational Safety and Health Administration, 2009).

The ACA provisions are one step forward in institutionalizing and catalyzing prevention. Even after current ACA provisions go into effect, the health care system and its reimbursement structure needs to do more to incentivize the necessary community-based prevention. Such community-based prevention efforts also aid in the management of existing chronic diseases and injuries and thus reduce costs and better meet the health needs of communities across our nation.

As we reform and redesign the health care system, we need to explicitly take the issue of equity into account, since anything done to reformulate how care is delivered can either mitigate or exacerbate the problem of inequity. Therefore, quality improvements to any health care component (e.g., prevention, access, and quality) have to embrace principles of cultural competency, diversity, and equity.

We need to create a coherent, comprehensive, and sustainable health care system that is culturally and linguistically appropriate, affordable, effective, and equally accessible to all people—especially disenfranchised populations. The overall health system should start with community strategies—reducing the likelihood that people will get sick or injured in the first place and helping to maintain the well-being of those who are already sick and injured. The overall system should also offer a full set of services (e.g., medical, dental, mental health, and vision), including screening, diagnostic, and disease management services, within the communities where people live.

We need adequate community prevention strategies that target the factors underpinning why people get sick and injured in the first place. Health care is vital but alone it is not enough. The health care system has great strength in its committed providers and in its ever-improving diagnosis, procedures, and medicines. Many formerly fatal diseases are now treatable and even curable. Yet, as important as it is to improve the quality of health care services, it is only part of the solution to improving health and reducing health inequities. Patterns of disease and injury that follow the socioeconomic status gradient would still remain (Adler and Newman, 2002). While health care is vital, there are three reasons why addressing access to and quality of health care services alone will not significantly reduce disparities:

1. Health care is not the primary determinant of health. Of the thirty-year increase in life expectancy since the turn of the century, only about five years of this increase are attributed to health care interventions (Pincus, Esther, DeWalt, and Callahan, 1998). Even in countries with universal access to care, people with lower socioeconomic status have poorer health outcomes (IOM, 2000a).

2. Health care treats one person at a time. By focusing on the individual and specific illnesses as they arise, medical treatment does not reduce the incidence or severity of disease among groups of people because others become afflicted even as others are cured (Smedley et al., 2003).

3. Health care intervention often comes late. Health care and intervention play important restorative or ameliorating roles after disease occurs. However, many of today's most common chronic health conditions, such as heart disease, diabetes, asthma, and HIV/AIDS, are never cured. It is extremely important to prevent them from occurring in the first place and, when they occur, their ongoing prognosis will depend on a number of factors in addition to health care.

In order to successfully address inequities in health and safety, we must pose the following questions: Why are people getting sick and injured in the first place? What impedes their ability to recuperate? Are their neighborhoods conducive to good health? What products are sold and promoted? Is it easy to get around safely? Is the air and water clean? Are there effective schools and work opportunities? Are there persistent stressors in the environment, and what is the long-term impact of this stress on health? The frequency and severity of injury and illness are not inevitable.

People's health is strongly influenced by the overall life odds of the neighborhood where they live. Indeed, place matters. In many low-income urban and rural communities, whole populations are consigned to shortened, sicker lives. While residential segregation has declined overall since 1960, people of color are increasingly likely to live in high-poverty communities (Poverty and Race Research and Action Council, 2005). Racially and economically segregated communities are more likely to have limited economic opportunities, a lack of healthy options for food and physical activity, increased presence of environmental hazards, substandard housing, lower-performing schools, higher rates of crime and incarceration, and higher costs for common goods and services (the so-called “poverty tax”) (Smedley, Jeffries, Adelman, and Cheng, 2008).

Conversely, people are healthier when their environments are healthier. For example, in African American census tracts, fruit and vegetable consumption increases by 32 percent for each supermarket (Morland, Wing, Roux, and Poole, 2002). When states moved to require infant car seats, the impact of policy far exceeded that of education in changing norms and thus behavior: usage for infants went from 25 percent maximum to nearly universal, and death and injury from car crashes decreased (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2004).

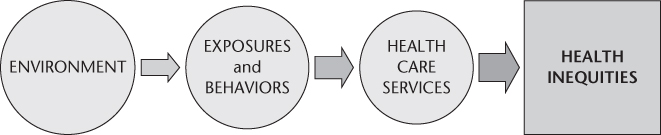

Taking a step from a specific disease or injury reveals the behavior (e.g., eating, physical activity, and violence) or exposure (e.g., stressors and air quality) that increases the likelihood of the injury or disease. Through an analysis of the factors contributing to medical conditions that cause people to seek care, researchers have identified a set of nine behaviors and exposures strongly linked to the major causes of death: tobacco, diet and activity patterns, alcohol, microbial agents, toxic agents, firearms, sexual behavior, motor vehicles, and inappropriate drug use (Mokdad, Marks, Stroup, and Gerberding, 2004). Limiting unhealthy exposures and behaviors enhances health and reduces the likelihood and severity of disease and injury. In fact, these exposures and behaviors are linked to multiple medical diagnoses, and addressing them can improve health broadly. If we take a second step, we see that specific elements of the environments in which people live are major determinants of our exposures and behaviors and thus of our illnesses and injuries.

This framework, Take Two Steps to Prevention (detailed further in the following sections and illustrated in Figure 12.1 below) was developed as a tool for analyzing the underlying causes of illness and injury and health inequities and identifying the key opportunities for intervention and prevention. Take Two Steps to Prevention presents a systematic way of looking at needed health care services and then traveling back to the exposures and behaviors that affect illness and injury and then back to the underlying community conditions that shape patterns of exposure and behavior.

Take Two Steps to Prevention

Starting with Health Care Services

Health care services aim to improve health outcomes by focusing on identifying and treating specific medical conditions (e.g., heart disease, diabetes, and infections) with health care services. High-quality health care can prevent the onset of some medical conditions, diagnose problems early, reduce the severity of symptoms, and slow the progression of secondary conditions. The Institute of Medicine's Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care identified three primary ways to intervene to reduce health inequities through health care services (Smedley et al., 2003):

1. Increase access to care: Within our current system, lack of insurance and underinsurance, major barriers to accessing medical care, are not borne equally across racial and ethnic lines.

2. Improve quality of care (diagnosis and treatment): Unequal Treatment documents that “evidence of racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare is, with few exceptions, remarkably consistent across a range of illnesses and healthcare services” Unequal Treatment reveals that differences in diagnosis, quality of care, and treatment methods lead to consistently poorer health outcomes among people of color.

3. Implement culturally and linguistically appropriate care: A culturally competent system of care is measured both by achieving the desired health outcome and patient satisfaction with medical encounters.

The First Step: From Health Care Services to Exposures and Behaviors

Health care alone cannot eliminate health disparities. The first step is from health care to exposures and behaviors. Limiting unhealthy exposures and behaviors enhances health and reduces the likelihood and severity of disease. Through an analysis of the factors contributing to medical conditions that cause people to seek care, researchers have identified a set of nine behaviors and exposures strongly linked to the major causes of death: tobacco, diet and activity patterns, alcohol, microbial agents, toxic agents, firearms, sexual behavior, motor vehicles, and inappropriate drug use (Davis, Cook, and Cohen, 2005). These behaviors and exposures are linked to multiple medical diagnoses, and addressing them can improve health broadly. For example, tobacco is associated with a number of health problems including lung cancer, asthma, emphysema, and heart disease. Diet and activity patterns are associated with cardiovascular and heart disease, certain cancers, and diabetes, among other illnesses.

As a result, reducing exposures and unhealthy behaviors decreases the risk of multiple injuries and illnesses. It is also important to include analysis of exposure to the stressors of poverty, racism, lack of opportunity, etc. Exposure to these stressors affects low-income communities and people of color disproportionately, and similar to the nine listed above are contributing factors in multiple health conditions and opportunities for intervention.

The Second Step: From Exposures and Behaviors to the Environment

Exposures and behaviors are determined or shaped by the environments in which they are present, defined as anything external to individuals and shared by members of a community. Exposures, of course, are shaped by what in the environment one is exposed to, and behaviors are shaped (encouraged or discouraged) by what is available in communities and the norms that communities help shape. Taking the second step from exposures and behaviors to the environment, presents a tremendous opportunity to reduce health inequities by preventing illness and injury before their onset. The environment includes root factors (e.g., poverty, racism, and other forms of oppression), institutions, and community factors. THRIVE (Tool for Health and Resilience in Vulnerable Environments), a research-based framework created by Prevention Institute, offers a way to understand the community factors (Prevention Institute, 2004). THRIVE includes thirteen community health factors grouped into three clusters: people, place, and equitable opportunity. Similar work by other researchers confirms this overall approach. For example, in 2002 PolicyLink published very similar findings and factors in the report, Reducing Health Disparities Through a Focus on Communities.

The thirteen community THRIVE factors are organized into three interrelated clusters (see Figure 12.2): equitable opportunity, people, and place and either directly influence health and safety outcomes via exposures (e.g., air, water, soil quality; stressors) or indirectly via behaviors that in turn affect health and safety outcomes (e.g., the availability of healthy food affects nutrition). In addition, the environment also influences people's opportunity to access quality health care services, and these are included as a fourth cluster. The clusters are described here:

Figure 12.2 Community Clusters

Equitable Opportunity This cluster refers to the level and equitable distribution of opportunity and resources. Root factors, including poverty, racism, and lack of educational and economic opportunities are among the fundamental determinants of poor health, lack of safety, and health inequities. They each contribute to chronic stress and can build upon one another to create a weathering effect, whereby health greatly reflects cumulative experience rather than chronological or developmental age (Geronimus, 2001). Chronic stress increases risk for coronary artery disease, stroke, cognitive impairment, substance abuse, anxiety, depression, mood disorders, and accelerated aging and cancer (Adler and Newman, 2002). Further, economic and racial segregation is one of the most powerful forces shaping health in the United States. The availability of jobs with living wages, absence of discrimination and racism, and quality education all affect health and safety (Lantz et al., 1998; Smedley et al., 2008). This segregation is not inevitable; it has been established and maintained through government policy and investment and the practices of institutions and organizations (Adler, 2002). Examples include redlining (wherein low-income neighborhoods and neighborhoods with primarily people of color are identified for discriminatory investment by banks and other lenders, historically by drawing a red line on a map); discriminatory application of GI Bill housing benefits; unequal investment in schools and transportation (leaving low-income communities at an educational and geographic disadvantage, which restricts social and economic mobility and development leading to further concentration of poverty); and judicial rulings such as the Supreme Court's recent ruling (Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District) that reverses much of Brown v. Board of Education, which ruled that separate was not equal. Factors include:

- Racial justice, characterized by policies and organizational practices that foster equitable opportunities and services for all; positive relations among people of different races and ethnic backgrounds

- Jobs and local ownership, characterized by local ownership of assets, including homes and businesses; access to investment opportunities, job availability, and the ability to make a living wage

- Education, characterized by high-quality and available education and literacy development across the life span

People This cluster refers to the relationships between people, the level of engagement, and norms, all of which influence health and safety outcomes. For instance, strong social networks and connections correspond with significant increases in physical and mental health, academic achievement, and local economic development, as well as lower rates of homicide, suicide, and alcohol and drug abuse (Buka, 1999; Wandersman and Nation, 1998); children have been found to be mentally and physically healthier in neighborhoods where adults talk to each other (Wilkenson, 1999). Social connections also contribute to a community's willingness to take action for the common good which is associated with lower rates of violence (Sampson, Raudenbush, and Earls, 1997), and improved food access (Pothukuchi, 2005). Factors include:

- Social networks and trust, characterized by strong social ties among persons and positions, built upon mutual obligations; opportunities to exchange information; the ability to enforce standards and administer sanctions

- Community engagement and efficacy, characterized by local/indigenous leadership; involvement in community or social organizations; participation in the political process; willingness to intervene on behalf of the common good

- Norms/accepted behaviors and attitudes, characterized by regularities in behavior with which people generally conform; standards of behavior that foster disapproval of deviance; the way in which the environment tells people what is okay and not okay

Place This cluster refers to the physical environment in which people live, work, play, and go to school. Decisions about place have multiple direct and indirect effects on health and safety. For example, physical activity levels are influenced by conditions such as enjoyable scenery (Jackson, Kochtitzky, 2009), the proximity of recreational facilities, street and neighborhood design (CDC, Active Community Environments Factsheet), and transportation design (Hancock, 2000); and the presence of alcohol distributors in a community is correlated with per capita consumption (Schmid, 1995). Factors include:

- What's sold and how it's promoted, characterized by the availability and promotion of safe, healthy, affordable, culturally appropriate products and services (e.g., food, books and school supplies, sports equipment, arts and crafts supplies, and other recreational items); limited promotion and availability, or lack, of potentially harmful products and services (e.g., tobacco, firearms, alcohol, and other drugs)

- Look, feel, and safety, characterized by a well-maintained, appealing, clean, and culturally relevant visual and auditory environment; actual and perceived safety

- Parks and open space, characterized by safe, clean, accessible parks; parks that appeal to interests and activities across the life span; green space; outdoor space that is accessible to the community; natural/open space that is preserved through the planning process

- Getting around, characterized by availability of safe, reliable, accessible, and affordable methods for moving people around, including public transit, walking, and biking

- Housing, characterized by availability of safe, affordable, and available housing

- Air, water, and soil, characterized by safe and nontoxic water, soil, indoor and outdoor air, and building materials

- Arts and culture, characterized by abundant opportunities within the community for cultural and artistic expression and participation and for cultural values to be expressed through the arts

Health Care Services Over the course of our lives we also all want and need health care, including good medical, mental health, and dental services. As a starting point, people need to be able to obtain quality health and dental care, which means people need adequate and affordable health insurance. To help maintain health, people need preventive care and chronic disease management. In crisis situations, we need reliable, immediate, and qualified emergency responses. When we suffer from acute or chronic conditions, we hope for quality health care to treat or cure our conditions, or help us manage them. For all of these services, culturally and linguistically appropriate patient care is critical for communicating with patients and addressing health concerns within the cultural context of the patient. Factors include:

- Preventive services, characterized by a strong system of primary, preventive health services that are responsive to community needs

- Cultural competence, characterized by patient-centered care that is understanding of and sensitive to different cultures, languages, and needs

- Access, characterized by a comprehensive system of health coverage that is simple, affordable, and available

- Treatment quality, disease management, in-patient services, and alternative medicine, characterized by effective, timely, and appropriate in-patient and out-patient care including for dental, mental health, and vision

- Emergency response, characterized by timely and appropriate responses in crisis situations that stabilize the situation and link those in need with appropriate follow-up care

Clearly, local solutions to health and safety inequities are central to success. Local work complements broader national change, and local solutions often help shape profound, long-lasting federal changes. Altering community conditions, particularly in low-income communities of color where the memory and legacy of dispossession remains, requires the consent and participation of a critical mass of community residents. Thus strategies that reconnect people to their culture, decrease racism, reduce chronic stress, and offer meaningful opportunities are ultimately health policies. Effective change is highly dependent upon relationships of trust between community members and local institutions. The process of inclusion and engaging communities in decision making is as important as the outcomes, which should directly meet the needs of the local population. Strategies such as democratizing health institutions, as was envisioned with the creation of community health centers, foster increased civic participation and serve as a health improvement strategy.

A quality health care system and community prevention are mutually supportive and constitute a health system. While health care and community prevention are often thought of as separate domains and operate independently, they actually are synergistic. Health care institutions have critical roles to play in ensuring an emphasis on health within communities as a key part of the solution. Health services must recognize that the community locale is an essential place for service provision, for example, by expanding community clinics, providing school health services, and giving immunizations in supermarkets. An effective health care institution will also provide broad preventive services, such as screening and disease management that address populations at risk and those that already have illnesses.

Health care also has a role to play in improving community environments. It is one of the nation's largest industries and is often the largest employer in a low-income community. As such, health care institutions can support pipeline development to recruit, train, and hire people from the community, especially from underserved sectors. They can also advocate for community changes that will positively impact disease management, such as healthier eating and increased activity; improve the local economy by purchasing local products; create a farm-to-institution program to incorporate fresh, local produce and other foods into cafeteria or patient meals; reduce waste and close incinerators to reduce local pollution; and enhance staff and community access to fresh produce by establishing accessible farmers' markets or farm-stand programs. For example, Kaiser Permanente, the nation's largest HMO, has instituted farmers' markets in some of the communities it serves, providing healthy options for the residents, offering a needed place to purchase quality food, and strengthening the nearby local farms.

Equally, community prevention efforts should be a part of the strategy to foster health and reduce health disparities by improving the success of treatment and injury/disease management even after people get sick or injured. Illnesses such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, HIV/AIDS, and cancer require patients to do what the medical practitioner requests, such as eat healthy foods and be more active. It is important for health care institutions to recognize the ways in which poverty and other social structures impede a patient's ability to follow a doctor's recommendations. Disenfranchised people usually don't have safe places to walk or healthful food to eat. Overwhelmed with the requirements of work and daily life and coping with transportation and child-care issues, poor people can have more obstacles to keeping medical appointments as well. With community prevention efforts bolstering neighborhood environments and support structures, disease management strategies will be more effective.

Challenges and Opportunities to Achieving Health Equity Through Practice and Policy

Achieving equitable outcomes is challenging and will take concerted attention, leadership, and investment. The following challenges and opportunities are based on interviews with local health officers that informed the development of Health Equity and Prevention Primer (Prevention Institute, 2008) funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation as part of the project Advancing Public Health Advocacy to Eliminate Health Disparities. Pinpointing specific challenges and opportunities is key to shaping responsive solutions.

Challenges

1. We haven't embraced the problem of health inequities at its roots.

We need to recognize that health inequities are rooted in historical policies and practices and are entrenched in social structures that create barriers to opportunity. This legacy remains invisible to many health care practitioners, policymakers, and the public. Practitioners and community spokespersons need to talk about race and social justice in new ways and often need guidance to do so effectively.

2. We don't have a good playbook for how to do this.

The people and institutions working for reform need more guidance and information in order to identify and realize the most effective, sustainable changes. They often lack standardized, comparative data; documented examples of success; protocols for adaptation, with attention to fidelity of core elements; a set of best practices; a framework to measure outcomes and successes; and clear goals for the community.

The roles of different players are not well defined. Many health issues can be traced to determinants that cross over into other public sectors, such as housing. Public health practitioners have indicated a need for guidance on strategies where public health can take the lead (Prevention Institute, 2008). Further, they don't always know how to coordinate with leadership in other sectors such as housing. In most cases, the charge to address health equity will require public health practitioners to step outside of the contemporary bounds of public health, but this will mean establishing effective communication channels, navigating turf issues, and clarifying shared goals and objectives.

Also, the role of other institutions needs clarification as part of a coherent effort. Banks, businesses, multiple government sectors, schools, and community groups all have a major influence on health equity outcomes, even though they may not realize it or consider it in their decision-making processes. While these players may not see themselves as having an active role, none should be taking actions that are detrimental to health outcomes.

3. A siloed system leads to a fragmented approach at best.

Even if there were a shared understanding of the root of health inequities, sectors are siloed without a mechanism to work collaboratively to provide a coherent, effective set of solutions. By and large, there is a lack of coordination and cross-fertilization across sectors, efforts, and disciplines (Prevention Institute, 2008). This is critical to address, because reducing health inequities cannot be achieved by any one organization or sector, let alone any single department or division within public health.

Not only are sectors siloed, but the health system itself is siloed. Even within public health departments, opportunities to create meaningful collaboration across divisions, sections, or departments are limited. Categorical funding—important because it provides dedicated resources to deliver essential programs and services—can reinforce siloed approaches. There is even a divide between public health and health care; the two don't work together systematically and strategically to catalyze, advocate for, and launch the kinds of solutions that can make a fundamental difference. Finally, community members are not consistently included in prioritizing problems or in shaping solutions.

4. Community-based, family-centered primary care is not a medical emphasis.

Medical reimbursement, prestige, and medical education norms can all favor specialization over community-based, family-centered primary care. Furthermore, there is a lack of value and incentive placed on allied health professionals, promotoras (i.e., community health workers), and patient navigators. We also need to incentivize preventive services and better train medical providers in prevention.

5. Disparities in health care are not an organizational priority for many U.S. hospitals.

Many hospitals consider disparities in care as a function of conditions beyond their control. They may be reluctant to openly address “disparities” collaboratively, because this might be viewed as an admission of inequitable care (Siegel et al., 2007). Often providers assume they administer equal care since it is their mission. Stratifying their publicly reported quality measures by patient race and ethnicity would be one way to confirm their assumption or identify areas for quality improvement work.

6. Health equity isn't embedded in most people's job descriptions; there are many competing demands.

Research and practice in equitable outcomes tend to occur either as a small part of one's job or as a specialty focus of a small group of experts within an organization. The challenge here is how to embed health equity into research and practice across and within organizations, bringing these efforts to scale, infusing them into the broader organizational culture, and propelling them to center stage.

Opportunities

1. Health reform can be leveraged.

The Affordable Care Act includes a number of provisions that support a focus on underlying determinants of health and health equity, including the creation of a Community Transformation Grant program and the development of a National Prevention and Health Promotion Strategy. As health reform moves into implementation, it is critical that we highlight opportunities in all parts of the bill to connect clinical and community efforts and to focus on underlying determinants of health. The economic case for community-oriented prevention is solid (TFAH, PI, UI, and NYAM, 2008). With a growing awareness of community conditions for health, of tools that help make the case for addressing the underlying causes of health inequities (e.g., the PBS documentary series, Unnatural Causes: Is Inequality Making Us Sick?), and of the role of culturally appropriate, family-centered primary care, the pieces are in place to inform a more equitable, health-producing health system that is sustainable for all. To reduce inequities in health and safety, health reform implementation will need to maintain or increase investment in community-level prevention to decrease the number of people getting sick and injured; shift the emphasis from delivery of services (quantity) to improved health and safety (quality), particularly for vulnerable populations; reimburse for health care services, including preventive health care services that are delivered in communities; and ensure that system redesign enables the delivery of high-quality, culturally appropriate health care services for all.

2. It makes a lot of sense to focus at the state and local levels to address inequities.

Over the past several decades, there has been a general shift toward moving social programs from federal to state governments—a “devolution of authority.” Although federal initiatives provided the catalyst for health disparities to emerge as a public health issue, states are now poised to build on this opportunity and take the lead in sponsoring social programs that help reduce inequities. States are seen as a key place for health reform (Prevention Institute, 2008). Numerous health departments are engaging in efforts to advance health equity in communities large and small, urban and rural (Prevention Institute, 2008). In some cases, departments are deeply engaged in equity-focused work and are creating organizational structures and processes to focus specifically on health equity. In other cases, departments are engaged in supportive ways, sharing resources and information with community-based organizations that are providing more of the leadership and energy behind equity efforts. Many health departments are in an exploratory phase, examining internal interest and opportunities for addressing health equity.

Focusing equity efforts at the state and local levels is promising because many of the social and economic health determinants can be acted upon at these levels. For example, a local health department seeking to ensure quality affordable housing can work with the local community development and housing agency to discuss proposed projects, provide data about their potential health impacts, and work with local residents to explore their needs and concerns. Commitment and optimism about health equity becoming a centerpiece of the public health agenda remains high within health departments as they strive to make the internal and external changes necessary to take on an equity-related focus. There remains a need to further coalesce and project a stronger community voice, though partnerships with community organizations and policymakers have proven successful (Prevention Institute, 2008).

3. Our ability to map, measure, and track is improving significantly.

Emerging technologies, coupled with new and expanding sources of data, are providing significant support in reducing health inequities. For instance, community-based organizations and public agencies are increasingly using maps to support social and economic change on a community level. Mapping is a powerful tool in two ways: (1) it makes patterns based on place much easier to identify and analyze and (2) it provides a visual way of communicating those patterns to a broad audience, quickly and dramatically (PolicyLink, 2001). Projects such as Healthy City in Los Angeles allow users with minimal technical skill to create a variety of maps that highlight patterns of community resources, community conditions (e.g., income level or air quality), and health and social outcomes (e.g., disease rates or high school graduation rates). These maps provide stark illustration of community issues and can be used as the focus of community decision making and organizing and as important evidence during advocacy campaigns.

There is a strong national trend toward using community-level health indicators and indicator data to monitor change over time, increase accountability among policymakers, and engage communities in a dialog about local priorities. This movement is being supported by national institutions and resources, such as the Community Health Status Indicators Project, and implemented at regional and local levels. Well-selected community health indicators provide comparative data over time and are a step toward ensuring that actions are aligned with health interests, that the social determinants of health are monitored and acted upon, and that there is accountability for improving community conditions. The process of selecting indicators and collecting data—in essence selecting what will be measured—is in itself valuable as a venue for developing community capacity, building partnerships, and engaging community members, along with representatives from the public and private sectors, in identifying, prioritizing, and setting benchmarks related to health and well-being. Prevention Institute conducted a review of more than ninety indicator reports and report cards for the study Good Health Counts: A 21st Century Approach to Health and Community for California (2007). This review revealed that success was achieved through both a carefully developed set of indicators that reflect the determinants of health within the community and a well-orchestrated, transparent process.

Movement toward the use of electronic medical records and shared data among hospitals also holds promise for examining differences in access and equity in hospitals and clinics. As hospitals and clinics move toward electronic systems, the capacity to analyze differences by race and ethnicity increases as does the potential to address issues of high rates of missing race/ethnicity data—a key parameter for establishing the presence of disparities. Taking appropriate steps to protect privacy, we can link this data to GIS mapping to yield powerful information about the impact of community environment on health.

4. What's good for our natural environment is good for our health.

The mounting concern over environmental degradation and the increased focus on prioritizing solutions have introduced an opportunity to align issues of health and health equity with those of the environment and improve both simultaneously. For instance, greenhouse gas emissions are bad for the environment generally, accelerate climate change, and also have direct repercussion on health (e.g., asthma rates). In our efforts to solve these challenges, we can build powerful partnerships and address health issues that might otherwise be diminished. Strategically improving the physical environment could reduce the number of people getting sick and injured in the first place as well as the severity of those diseases. In effect this could reduce the demand for health care services and the burden on the health care system, which has the potential to increase the accessibility and affordability of quality health care and reduce the ecological footprint of our health care institutions.

Shifting toward a more sustainable food system and altering our transportation systems to support public transportation, walking, and biking, are among the initiatives that hold multiple environmental and health benefits by virtue of reducing greenhouse gases and our dependence on fossil fuels while improving air quality and increasing physical activity. There is potential to engage in strategies that simultaneously improve environmental conditions and support the health of vulnerable populations. Policies and practices are needed to improve the environmental and health conditions of communities—including ensuring clean air and water; preserving agricultural lands; reducing exposure to toxins; and providing economic opportunity, quality housing, and safe streets. However, such work must be done cautiously. For instance, rises in gas prices without simultaneous expansion of public transportation may have a positive impact in terms of greenhouse gases but can have disastrous effects on low-income people who live in communities that have been designed around automobile travel and where access to employment and resources such as healthy food are contingent on driving. As another example, popular “cap and trade” policies need to be implemented with safeguards against high polluters moving into communities with limited political capital to oppose such moves.

5. Internal organizational diversity helps to move along an equity-focused health agenda.

Achieving greater diversity within the health professions has been identified as a key strategy for ensuring a culturally competent workforce. Greater diversity across all levels of an organization can seed new and creative strategies for tackling health inequities. A number of health organizations are currently at the forefront of efforts to address health equity, and all these organizations—including health departments, health care organizations, and community-based organizations—have the opportunity to increase the diversity of their staffs. Diversity goes beyond racial and ethnic diversity to include factors such as age, gender, socioeconomic status, sexual preference, and professional skills. Ways to build and sustain diverse leadership include proactive efforts to recruit, hire, train, and retain staff that will contribute to diversity (Prevention Institute, 2008). Many organizations explicitly looking to address health equity have found that workforce development strategies can build the capacities of current staff and attract skilled and committed individuals to partake in the mission to achieve health equity. Organizations, as a result, seed new and creative ideas for tackling health inequities.

Local Solutions for Advancing Equity in Health and Safety

Community Solutions

Strengthen communities where people live, work, play, socialize, and learn.

C1 Build the capacity of community members and organizations. Capacity building enables the residents and grassroots groups affected by poor health outcomes to better solve the community problems undermining health and safety. Strategies include:

- Train public sector staff to encourage local capacity building and to empower residents to take action in partnership with city and county governments and community-based organizations to improve their neighborhood conditions.

- Invest in both established and developing community organizations. Encourage and strengthen the capacity of these and other institutions and of individuals via financial support, technical assistance, and sharing best practices.

- Foster structured community planning and prioritization efforts to implement neighborhood-level strategies to address unfavorable social conditions.

C2 Instill health and safety considerations into land use and planning decisions. Land use, transportation, and community design (the built environment) influence health, including physical activity, nutrition, substance abuse, injuries, mental health, violence, and environmental quality. Strategies include:

- Ensure that health, safety, and health equity are accounted for in General Plans, Master Plans, or Specific Plans; zoning codes; development projects; and land-use policies.

- Engage community residents in developing zoning laws and general plans to integrate health and equity goals and criteria into community design efforts.

- Train public health and health care practitioners to understand land use and planning and to advocate for policies that support health and safety.

C3 Improve safety and accessibility of public transportation, walking, and bicycling. Transportation is the means to accessing key destinations such as schools, workplaces, hospitals, and retail venues. Shifting the dominant mode of transportation from driving to greater public transportation use, walking, and/or bicycling is a key step to increasing physical activity, reducing traffic injuries, and reducing developmental and respiratory illnesses from poor air quality. Strategies include:

- Implement land-use strategies such as high-density, mixed-use zoning, transit-oriented development, and interconnected streets that promote walking and bicycling as a means of transportation.

- Adopt complete streets policies in state and local transportation departments to ensure that roads are designed for the safety of all travelers including pedestrians, bicyclists, wheelchairs, and motor vehicles.

- Ensure that public transportation options are safe, easily accessible, reliable, and affordable.

- Design public transit routes to connect community residents to grocery stores, health care, and other essential services.

- Prioritize federal transit funding toward biking, walking, and public transportation.

C4 Enhance opportunities for physical activity. Home, school, and community environments can either promote or inhibit physical activity. Physical activity is essential to preventing chronic illnesses and promoting physical and mental health. It is imperative to establish a foundation of activity behaviors from an early age and to provide environments with access to parks, open space, and recreational facilities that support people in attaining the daily recommended levels of physical activity (Active Living Research, 2005). Strategies include:

- Develop and promote safe venues and programming for active recreation. Ensure parks, playgrounds, and playing fields are equitably distributed throughout the community.

- Facilitate after-hour (joint) use of school grounds and gyms to improve community access to physical activity facilities.

- Require recess and adopt physical education policies to ensure all students engage in developmentally appropriate moderate-to-vigorous physical activity on a daily basis.

- Establish state licensing and accreditation requirements/health codes and support implementation of minimum daily minutes of physical activity in after-school programs and child-care settings.

C5 Enhance availability of healthy products and reduce exposure to unhealthy products in underserved communities. The food retail environment of a neighborhood—the presence of grocery stores, small markets, street vendors, local restaurants, and farmers' markets—plays a key role in determining access to healthy foods. Communities of color and low-wealth neighborhoods are most often affected by poor access to healthful foods (Larson, Story, and Nelson, 2009). Research suggests that the scarcity of healthy foods makes it more difficult for residents of low-income neighborhoods to follow a good diet compared with people in wealthier communities (Sloane et al., 2003). Strategies include:

- Invest in Fresh Food Financing Initiatives to provide grants, low-interest loans, training, and technical assistance to improve or establish grocery stores, small stores, and farmers' markets in underserved areas.

- Encourage neighborhood stores to carry healthy products and reduce shelf space for unhealthy foods through local tax incentives, streamlined permitting, and zoning variances.

- Ensure grocery stores, small stores, and farmers' markets are equipped to accept Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) (formally known as the Food Stamp Program) and Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) benefits.

- Establish and enforce regulations to restrict the number of liquor stores and their hours of operation.

C6 Support healthy food systems and the health and well-being of farmers and farmworkers. What farms grow, how they grow it, and how it gets to the consumer have a profound impact on what we eat, on our health, and on our environment. U.S. farm policy and agricultural research and education have contributed to the proliferation of industrial farms that grow grains, oil seeds, corn, meat, and poultry that serve as raw ingredients for cheap soda, fast food burgers, and other highly processed products. These industrial farms pollute the air, water, and soil while harming our nutritional health. Small- and mid-size farmers are struggling to make a living under the current system. Farmers of color face discrimination in access to loans. Farmworkers are exposed to hazardous levels of pesticides (Reeves, Katten, and Guzman, 2002), dangerous working conditions, and poor wages and living conditions. Strategies include:

- Support small- and mid-sized farmers, particularly farmers of color, immigrants, and women through grants, technical assistance, and help with land acquisition, marketing, and distribution.

- Establish incentives and resources for growers to produce healthy products, including fruits, vegetables, and foods produced without pesticides, hormones, or nontherapeutic antibiotics.

- Establish policies that support the health and well-being of farmworkers, including enforcing occupational safety and health laws and regulations as well as banning pesticides that may pose health risks. Government entities can also facilitate wage increases for farmworkers by providing grants and incentives for growers to engage in labor-sharing strategies with other growers.

C7 Increase housing quality, affordability, stability, and proximity to resources. High-quality, affordable, stable housing located close to resources leads to reduced exposure to toxins and stress, stronger relationships and willingness to act collectively among neighbors, greater economic security for families, and increased access to services (including health care) and resources (such as parks and supermarkets) that influence health. Strategies include:

- Support transit-oriented development and other policies and zoning practices that incentivize density, mixed-use, and mixed-income development.

- Ensure that housing standards; building permits for new buildings and rehabilitation; and housing inspections include safety and health considerations regarding design, the use of materials, and construction requirements.

- Protect affordable housing stock via rent control laws and condominium conversion policies, increase funding for emergency housing assistance, and maintain single-room-occupancy hotels.

- Support home ownership by creating community land trusts, increasing funds for and utilization of first-time home buyer programs, and establishing inclusionary zoning ordinances.

C8 Improve air, water, and soil quality. Environmental toxins present in air, water, soil, and building materials, including lead in soil and buildings, air pollution from motor vehicle traffic, and water pollutants, such as oil and human waste, have a substantial effect on health. Strategies include:

- Minimize diesel trucks in residential neighborhoods to reduce exposure to diesel particulates.

- Expand monitoring of air and water quality for impact on low-income and vulnerable populations.

- Enforce national water quality standards.

- Strengthen penalties for industrial and agricultural polluters.

- Replicate effective local lead abatement programs.

- Require public health input on air and water pollution impacts in local land use planning and development decisions.

C9 Prevent violence using a public health framework. Violence contributes to premature morbidity and mortality and is a barrier to health-promoting activities, such as physical activity, and to economic development. Strategies include:

- Invest in citywide, cross-sector planning and implementation with an emphasis on coordinating services (Weiss, 2008), programming, and capacity building in the most highly impacted neighborhoods, drawing on such tools as the UNITY RoadMap (Prevention Institute, 2008).

- Support local intervention models to reduce the immediate threat of violence, such as the Chicago CeaseFire model (Skogan, Hartnett, Bump, and Dubois, 2008).

- Institute changes in clinical and organizational practices in health care settings to support and reinforce community efforts to prevent intimate partner violence, which results in injury and trauma from abuse, contributes to a number of chronic health problems (Family Violence Prevention Fund, n.d., The Facts on Health Care and Domestic Violence) and disproportionately impacts immigrant women (“The Facts on Immigrant Women and Domestic Violence,” Family Violence Prevention Fund, n.d., The Facts on Immigrant Women and Domestic Violence; Salber and Taliaferro, 2006).

C10 Provide arts and culture opportunities in the community. Artistic and cultural institutions have been linked with lower delinquency and truancy rates in several urban communities (Stern and Seifert, 2000), and participation in the arts has been associated with academic achievement, election to class office, school attendance (Heath et al., 1998), appropriate expression of anger, effective communication, increased ability to work on tasks, less engagement in delinquent behavior, fewer court referrals, improved attitudes and self-esteem, greater self-efficacy, and greater resistance to peer pressure (Catterall, 1997). Strategies include:

- Support community art centers and other opportunities for creativity in the community.

- Integrate art and creative opportunities into existing programs and businesses.

- House art commissions within state or city government.

- Work with large art institutions, local policymakers, and residents to bring “Big Art” (e.g., museums and orchestras) to low- and middle-income communities.

- Implement a policy to receive a portion of every ticket sold in the community for movies, sporting events, etc. as an alternate source of funding for arts and culture. Another funding mechanism involves redirecting a portion of hotel and car rental taxes, since art contributes to enhancing the community.

Health Care Service Solutions

Enhance opportunities within underserved communities to access high-quality, culturally competent health care with an emphasis on community-oriented and preventive services.

HC1 Implement and extend health reform efforts in order to provide high-quality, affordable health coverage for all. Everyone, including the most vulnerable populations, should have equal access to health care, including health care, dental, vision, and mental health services. There currently are a disproportionate number of racial and ethnic minorities who either do not have any health insurance or are enrolled in “lower-end” health plans (Smedley et al., 2003) and this could persist after ACA implementation. Strategies include:

- Equalize access to high-quality health plans to limit fragmentation of health care services. For example, Medicaid beneficiaries should be able to access the same health services as privately insured patients (Smedley et al., 2003).

- Ensure that all eligible children and families enroll in and access the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP).

- Support safety net hospitals through state insurance coverage and state and local subsidies (Smedley, 2008).

- Ensure equitable support for dental and mental health services.

- Improve access through equitable and fair sharing of health care costs; streamline public health insurance enrollment and increase affordability of services within existing public programs, such as Medicaid; evaluate outreach to and enrollment of underserved populations; and support state and local legislative proposals for universal access to quality health care.

HC2 Institute culturally and linguistically appropriate screening, counseling, and health care treatment. Culture shapes beliefs, behavior, and expectations surrounding health and health care. Physicians and other health care providers should deliver quality services in a culturally competent and sensitive manner. This approach can increase patient satisfaction, patient adherence to treatment plans, and the probability of improved health outcomes. Strategies include:

- Adopt standards of practice that are sensitive to the language and cultural needs of all patients.

- Provide training for providers to conduct screening, counseling, and treatment in both a culturally appropriate and sensitive manner.

- Promote culturally and linguistically appropriate screening programs for specific populations, such as Asian women for cervical cancer and other targeted groups for breast and cervical cancer.

- Ensure an effective communication strategy that takes into account the patient's health literacy and preferred language.

- Ensure patient-system concordance (i.e., a setting of care delivery that optimizes patient adherence and a sense of security and safety).

HC3 Monitor health care models/procedures that are effective in reducing inequities in health and data documenting racial and ethnic differences in care outcomes. Detailed documentation of health care models/procedures will delineate the key elements of success. Currently, hospital practices for data collection vary widely as do the racial and ethnic classifications used. Strategies include:

- Standardize data: collect race and ethnicity data in all health institutions. Coordinate state standards for data collection on race and ethnicity with federal standards to track the health of minorities (Trivedi et al., 2005). Although it may be difficult to use data to compare institution-to-institution, hospitals can use it to identify existing disparities in care and track trends for different patient populations within a hospital.

- Coordinate data collection and data systems beyond individual institutions and the health care system: multiple partners from various sectors should be involved in outreach to different populations. For example, when addressing asthma management, school systems would be able to reach out to a broad range of school-aged children. Public health can play a key role in coordinating data collection at the community level and comparing it across systems.

- Disaggregate the data: ensure that data reflects differences within the broad categories of race and ethnicity (particularly among Latino and Asian/Pacific Islander populations), as well as income levels, and duration of residence in the United States. Adopt uniform patient classifications in health information technology to make quality analysis easier and quicker. Analysis should be included in quality improvement initiatives.

- Incorporate new accreditation standards and mandates that account for equitable health care.

- Apply emerging data practices to better determine what medical procedures are most effective for different populations. (One size does not necessarily fit all.) Explore the Expecting Success disparities collaborative as one such example. Upon submission of their LOI, although the majority (97 percent) of the 122 hospitals were collecting patient race and ethnicity data, almost none reported using the data for quality improvement purposes at that time. Currently, they are among the most likely to have begun using quality data to reduce inequities in care (Siegel et al., 2007).

HC4 Take advantage of emerging technology to support patient care. Recent advances in health care technology can strengthen medical treatment. To the extent that technology is used as an element of quality health care, it's important to ensure that these advances fully benefit everyone. Cell phones are one area where there is a high degree of market penetration among all groups and so we should capture their potential to support medical treatment so as not to exacerbate disparities. When technology is not equally available (e.g., computers in every home), alternatives should be provided that are efficacious. Strategies include:

- Institute electronic health records that protect privacy but ensure caregivers have all needed information.

- Use telephone and e-mail reminders to increase frequency of appointments and testing compliance, reduce failure to take pills, and encourage following procedures.

- Make tailored health information easily accessible and responsive.

HC5 Provide health care resources in the heart of the community. Strengthening the presence of health care services located in communities of high need reinforces the connection between health care and community and can remove pervasive access barriers such as inadequate transportation options or not being able to seek health care during traditional working hours. Strategies include:

- Support community-based clinics. Clinics have an essential role in improving community health and providing services for uninsured and underserved populations. Clinics should establish organizational practices to increase access to equitable health care. Health reform funds designated for community-based clinics should be used both to expand services and also to expand the role of the clinic as a hub for community health (e.g., development of intersectoral partnerships to work on issues affecting health such as housing and transportation).

- Expand availability of school-based health clinics.

- Provide support groups that enhance self-efficacy in engaging in healthy behaviors.

- Provide culturally appropriate care such as translation services, disease prevention counseling, advocacy for quality health care, and other services to patients directly in the community, not just in health care settings.

- Expand the use of community health workers. Reforming reimbursement is essential, including state grants and seed funding as resources (Smedley, 2008).

- Change the available work hours and locations to meet the needs of patients.

HC6 Promote a medical home model. Having a designated health provider for every patient and, ideally, every family has enormous benefits. Primary care becomes more accessible, continuous, comprehensive, family-centered, coordinated, compassionate, and culturally effective. Patient-centered care is given within a community and cultural context. In 2007, the American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Physicians, and American Osteopathic Association released the Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home. Far fewer people of color have a medical home, which is strongly associated with prevention, screening, and specialty care referral (Beal et al., 2007). Strategies include:

- Design interventions to incorporate detection, prevention, and management of chronic disease with full deployment of multidisciplinary teams that are family- and patient-centered.

HC7 Strengthen the diversity of the health care workforce to ensure that it is reflective and inclusive of the communities it is serving. The diversity of health care professionals is associated with increased access to and satisfaction of care among patients of color. States can adopt strategies such as loan repayment programs and service grants, health profession pipeline programs, and other incentives for service (Smedley, 2008). Strategies include:

- Train clinic providers to conduct culturally appropriate outreach and services.

- Address the imbalance of health care providers by offering incentives to work in underserved communities (Smedley, 2008). States could provide incentives that include funding graduate medical programs focusing on underserved populations, tuition reimbursement, and loan forgiveness programs that require service in Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs).