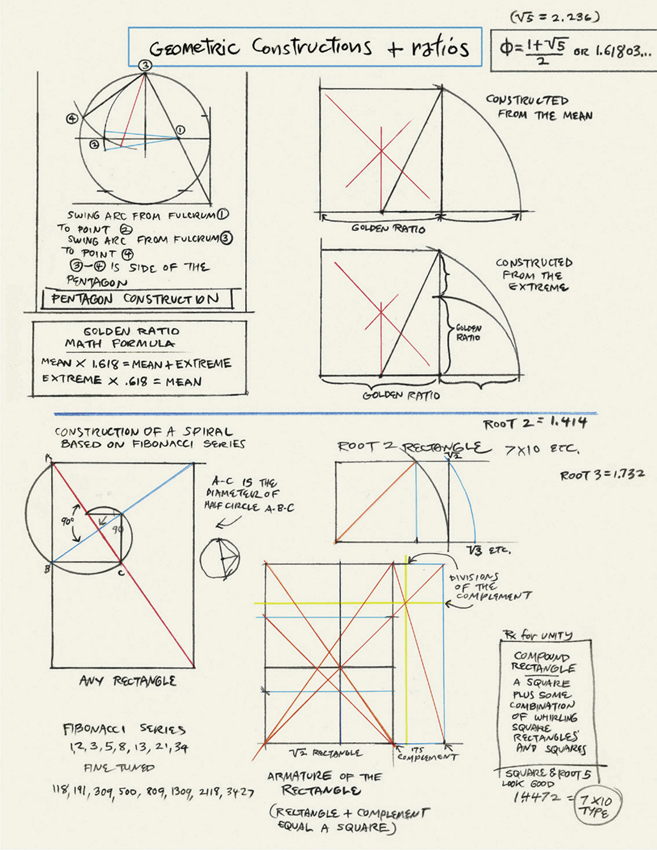

GEOMETRIC CONSTRUCTIONS AND RATIOS 1

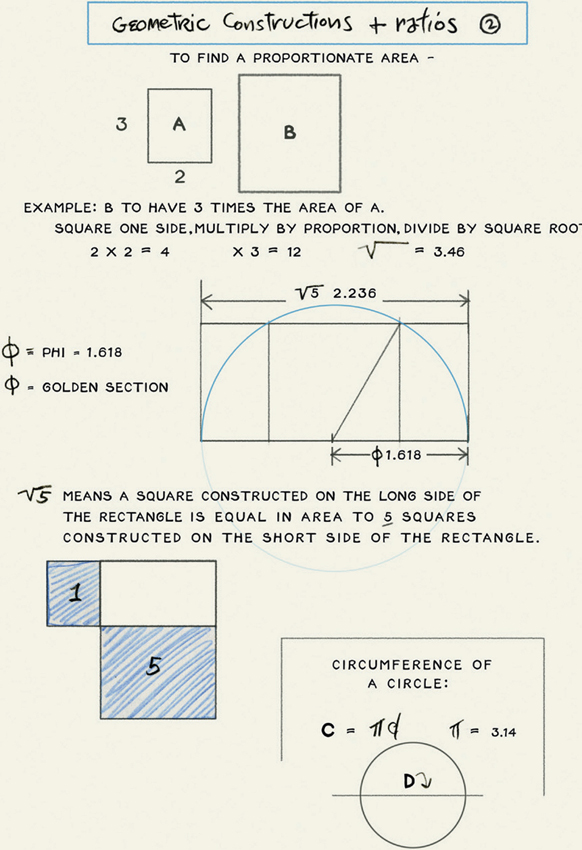

GEOMETRIC CONSTRUCTIONS AND RATIOS 2

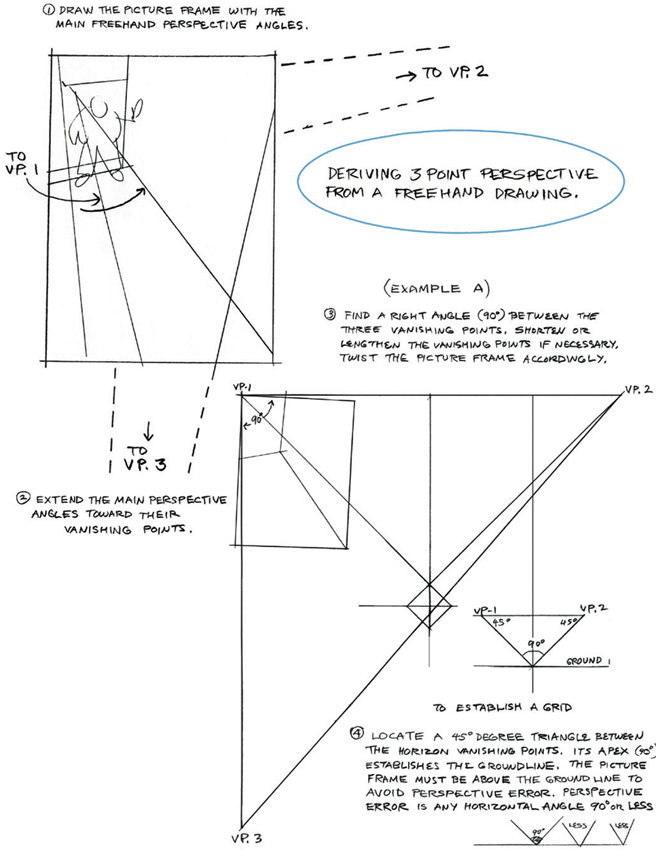

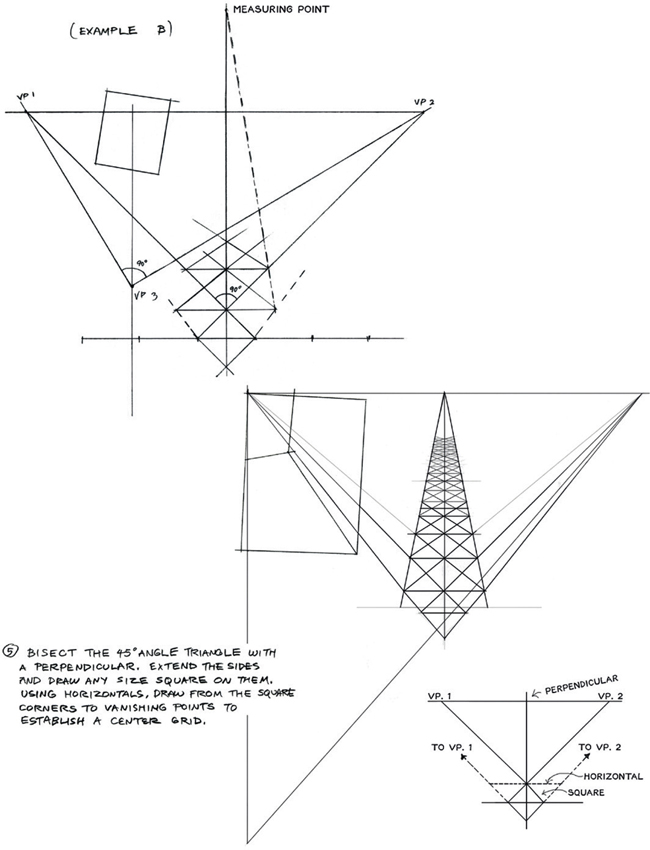

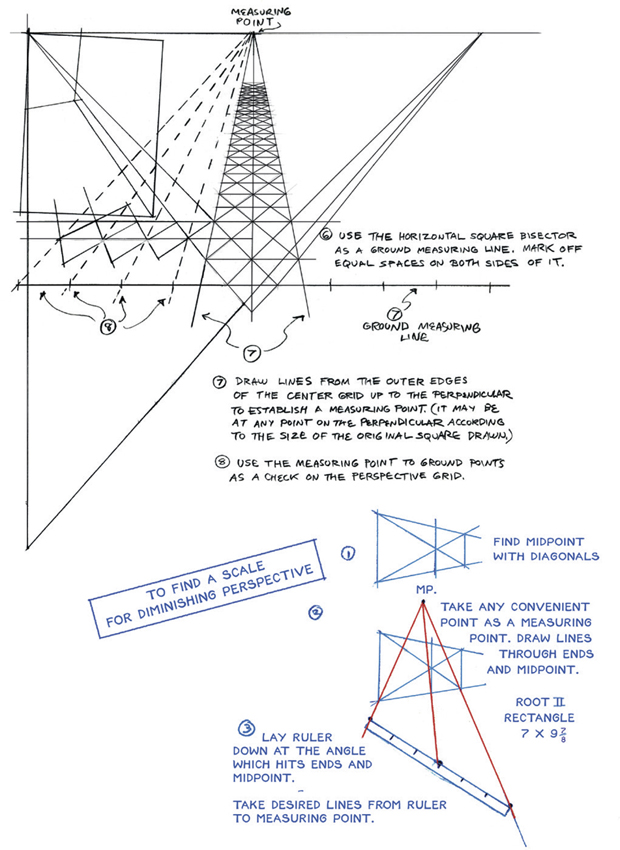

DERIVING 3-POINT PERSPECTIVE FROM A FREEHAND DRAWING

PERSPECTIVE

PERSPECTIVE

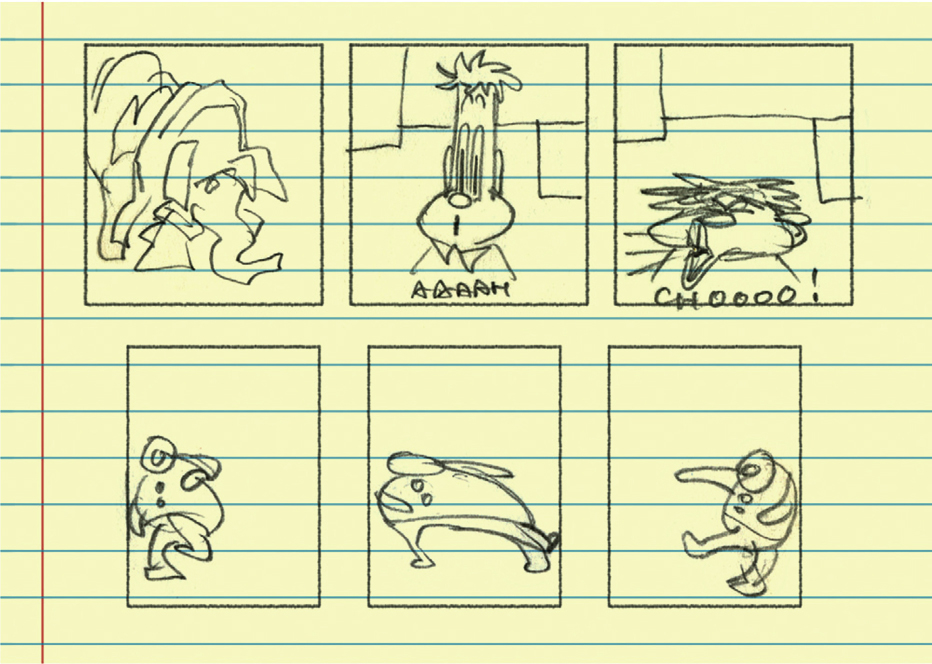

FORM FOLLOWING GESTURE IN ANIMATION

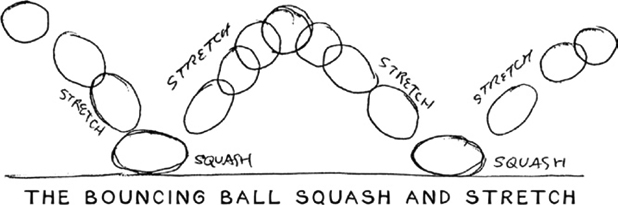

Some animators wish to avoid the cliché of the bouncing ball squash and stretch. In doing so, they either minimize or eliminate altogether the distortion of the parts of the animating figure. This not only robs the figure of its vitality but much of its humor as well. For caricature in animation must be not only caricature of the form in a model chart but caricature of the gesture as well.

The way to achieve a more sophisticated and interesting animation style is not to eliminate the “bouncing ball squash and stretch” but to enlarge on it.

This can be done by adding other forms and substances to the animator’s repertoire—forms with their own laws of expansion and contraction.

Besides rubber balls, there are cloth, leather, earth, leaves, coil springs, saplings, dough, jelly, meltables and liquids such as water, molasses, and grease.

The comic power of suggestion in the action of objects was well exploited by the early animators. The malleability of organic matter can still be exploited in new ways. It only needs an animator of wit to discover them.

ANIMATION NOTES, LONDON

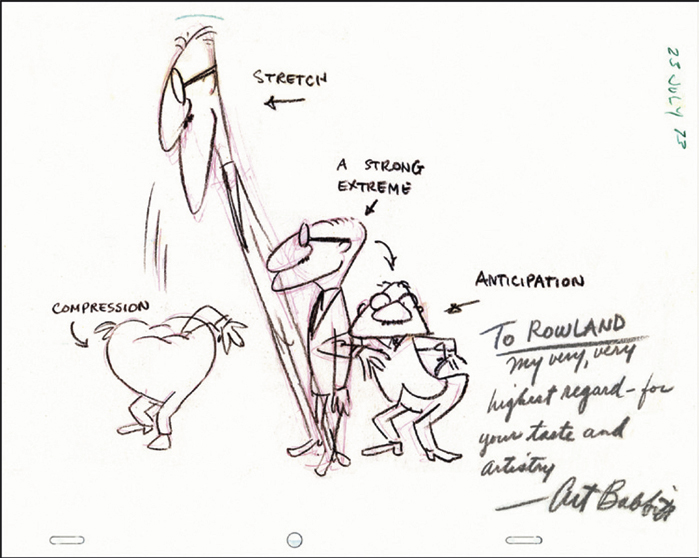

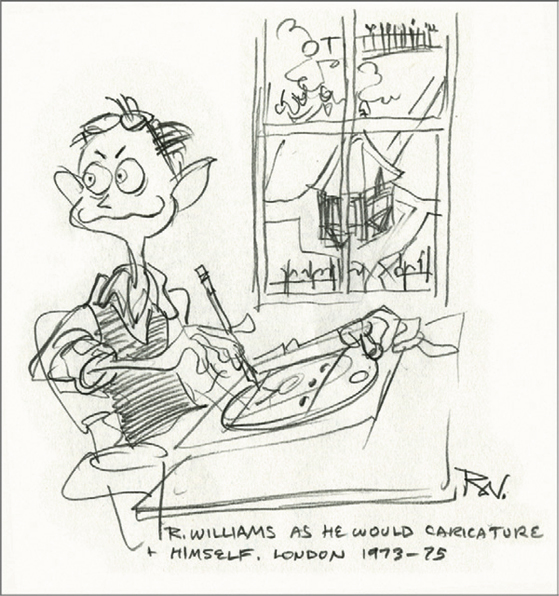

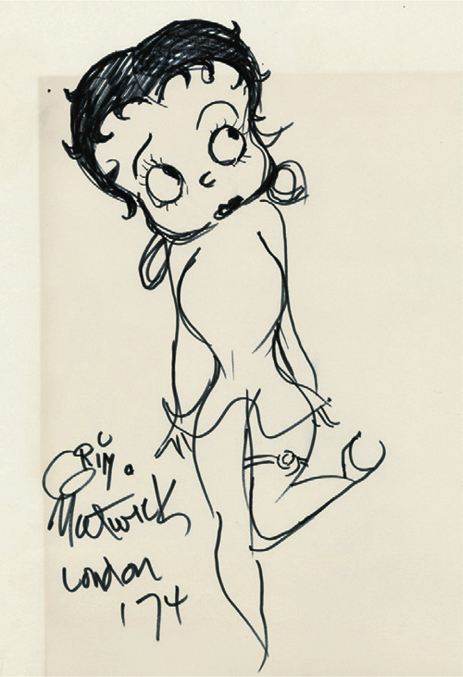

These are pages from a sketchbook produced in 1973 and 1974 while working at Richard Williams Studio in London. The material is based on lectures and conversations with the legendary animators Richard Williams, Art Babbitt and Grim Natwick.

Drawing by Art Babbitt (Collection: Suzanne Wilson)

Sketch of Art Babbitt lecturing at the Richard Williams Studio

Rowland and Suzanne Wilson caricatured by Richard Williams

GRIM NATWICK AT RICHARD WILLIAMS STUDIO, LONDON

Grim Natwick was considered one of the world’s greatest animators. He gave a series of talks to animators and was also available for informal conversation during this period (1973–74). We shared the same block of flats and I talked to him often at the studio and after hours. The following is a summation of these talks rearranged according to subject matter.

GRIM AND THE TRACK—At the time Grim was here I was working on Count Pushkin Vodka (The Trans-Siberian Express animated commercial) and searching for a way to visualize dramatically a musical track. Grim placed great emphasis on the track and the importance of getting to know it thoroughly in order to draw it. At the time he was here I had not started to evolve the theory of musical form being the basis for animation form. Although Grim never spoke of animation structure as being the same as music structure, on looking back, I see that a number of things he advocated fit into music structure. Art Babbitt’s successive breaking of joints and overlapping action is comparable to the idea of sounding a group of notes in succession, rather than simultaneously. I suspect that the best animators have worked intuitively to principles that are analogous with musical principles. Grim and Art never expressed them that way, exactly.

DRAWING/ECONOMY—The most controversial theory of Grim’s was to set up a series of related drawings and go into them and out of them and through them in the course of a scene. The animators here felt that the system was not economical due to the amount of mental calculation it took to incorporate a pose in a new way once you had used it. They found the numbering confusing and the doping difficult. Grim presented the idea as an economy and they rejected it on that basis.

Later in music class it occurred to me the analogy of Grim’s practice with musical practice. The practice of starting with a first and second subject, going through it, repeating it, et cetera.

I think that Grim’s idea could be called “using a series of HOME KEYS” (animation keys) and is vindicated on aesthetic grounds if not on economic ones.

This is what he said about it:

“Get key drawings that are so centralized that it is easy to get another similar drawing. Duplicate by exposing it differently. Plan it. Stop on a different drawing. Out of five or six different poses, find three or four positions to work around.

“Never think of one drawing. Think between three or four rough positions. Think of a series of drawings. Saving one drawing saves twenty minutes.

“Use your routine animation, then break away, and then go back into it. In lip sync animate the character in a three-quarter view. Leave the mouth off—in order to repeat or even reverse the drawings. Make a little hook-up and reverse them. On Snow White we never repeated drawings. (?) (Question mark added by RBW.) Milk everything you can out of everything you have.

“If you have a walk or run do it as a cycle so you can spend the time getting an interesting one.

“Don’t ever use a drawing just once if there is any possibility to use it again.

“Forget about in-betweens; get the key positions. Then find the nicest way to get from one position to another, remembering all the time that there are several more positions.

“Don’t let it all overlap. Don’t entirely lose the position you’re leaving until you’re ready to settle into the next pose. Keep a little contact with the last drawing. Hold onto something.

“Always think of at least three positions: the preceding, the present, and the forthcoming.

“Drive right into the main points. Leave out the frills but make the main thing look really right.”

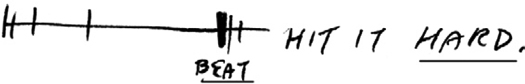

THE TRACK AND THE BEAT—Grim placed great emphasis on the beat in the track and using it to the utmost. He was an avid user of the metronome to set the beat in his head. He recommended making up a beat if there wasn’t one implicit in the track. This is what he said:

“Don’t treat the track lightly. That is your timing. For a walk, plan the action of the main body, then add arms and legs.

“The walk can be on three levels: a pattern for the legs, a different pattern for the body and a different pattern for the head.

“Split it into parts for a dance. Tie it to the sound track. Get that funny sound in there even if it’s only one frame. In walks we always had a funny frame in there some way.

“If you have a 24 beat, break it into parts: 16’s, 12’s, 8’s, and 4’s. Then trace them together.

“Stagger actions—all kept on beats or partial beats: feet on 16’s, body on 8’s, arms on 4’s, head on ? (question mark).

“Where possible try to get a costume you can break apart for levels.

“Example (For a cow)—the body bouncing on a 24-beat, the legs on 12’s, the tail on 8’s, a little bounce for the head—all traced together on 24 cycle with bell on a separate level.

“Get the big beats right—then you can almost ignore the little beats.

“Get the secondary beat visually secondary.”

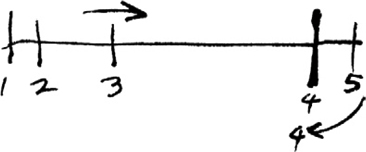

STACCATO ACTION—With Pushkin I went to Grim in need of a way to do a quick snapping action with a minimum of drawings. It was necessary to use a minimum because the drawings were highly rendered in a semi-realistic style. Grim laid out the spacing as below. Grim gave me the impression that this was an innovation for him and he dubbed it “Staccato Animation.”

SHOT ON 2’s—Soldier coming to attention: 1. At rest. 2. Leg and gun out. 3. Returning just past original position. 4. Heels displaced by downcoming foot. 5. At attention.

1. Extreme (hold)

2. Anticipation

3. In-between (Indicating start of, and direction of action.)

4. Impact

5. Extreme (Hold)

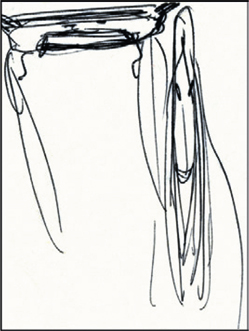

STRAIGHTS VERSUS CURVES—The practice of playing straights against curves was a pet idea of Grim’s and I came to appreciate the power of straight lines from him. Straight lines as an indication of strongly impelled action, that is, both in static drawings and in animation.

Grim said:

“When animating I always draw the paths of action on a separate piece of paper as a guide (loops, arcs, et cetera).

“Curves are always beautiful to watch. That’s why Bill Nolan used rubber hose animation. “Straight lines give power.

“Flow from one joint to another, moving arms in a lot of grooves.

“Play the angled joint against the straight.

“The head can be moving in a circle, hands in a figure-8, feet in loops or arcs.

“The patterns that are made in space by the moving parts—that is called the Poetry of Animation.

“What caused a splash? Where did it come from? Bring it out from exactly where the hit was, in straight lines.”

PACE OR TIMING—

“Make it faster by fast spacing or by fast timing. Normal spacing is on two’s; fast spacing on one’s. Timing must fit the sound track.

“To get snap into it—get out of orthodox timing.

“Use one drawing or two frames for normal anticipation but obviously more are needed to get into a run or a big action.

“Get a key drawing that is the best drawing you can make. Then you can hold it. Hold it six frames; eight, ten or twelve frames or even one and a half feet.

Very often a still drawing will help the picture—you can read the expression.

“Use wide spacing to hit the accent. Soften into your holds.

“For snap, space it as wide as you dare. It’s best to go past and then return. This applies to softening into a hold.

“Eight frames is almost but not quite a hold. Don’t think of eight frames as a hold. It’s just a hesitation, soften in and soften out of it.

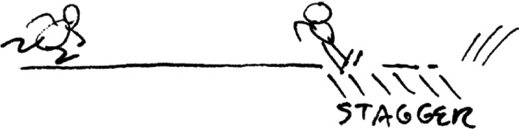

“On a figure running who skids to a halt: As he puts on the brakes stagger it 1, 4, 2, 3, 5, 4, 6, 5, 7. Have him go too far forward then come back. Slow down the pan as he gets his balance.”

“There is a difference in the spacing of a walk. The foot moves faster going forward to contact. The impact of the foot hitting the ground tends to slow it down. Keep the pan locked with the foot positions on the ground.

On a three-quarter-waltz time try a triple bounce.

Hitting a beat…I’ve never found it wrong to hit one frame or possibly two frames ahead of the beat.

Hit the downbeat on a dance when the weight is down.

The two great things in animation are spacing and timing.”

IN-BETWEENING—I always try to keep everything in three in-betweens or one. If I have four in-betweens, then I’ll draw one, making it three in-betweens.

To get snap into your action, don’t just in-between it, play one part against another. Play the joint against the straight line.

One of the defects of bad animation is too many close in-betweens. They make it jitter. To avoid ink and paint jittering avoid in-betweens too close together. Try to go farther. Avoid overlapping lines.

Jitter equals lines too close together. Make it broader. Avoid soft spacing.

Everything should be readable. Everything should be smooth, unless you deliberately jitter it because you want it that way.

The theory is to keep a little contact with the last drawing.

Hold onto something but the biggest danger is keeping in-betweens too close together.

QUOTES FROM GRIM NATWICK

I ask anybody’s opinion. I may not use it—but it may help me find what I’m fishing for.

Very often the improvement makes it easier.

Rough out fifty or sixty drawings a day. Test it and then chisel it down.

It’s easier to go too far and cut it down than to exaggerate it more.

Take those chances which might make it interesting or funny. It doesn’t have to be funny but it should be interesting. It should be funny if it’s unexpected.

Try something that you wouldn’t dare to do—and most of the time it will work.

Get every possible gag in if it doesn’t slow up the story.

Every time you increase your draftsmanship, you improve your animation.

I am an intense believer in going through a scene and roughing out ten feet or so; then getting the good drawings. Then you probably only need in-betweens.

A little bit of animation is like making a sentence using (Art) Babbitt’s alphabet.

Don’t be afraid to break a thing down.

Drive to one word or one point in each scene.

The eye will always follow the chief action.

Leave the best gags toward the end—the best at the last.

In a walk, the foot is always a little in front of the weight of the body.

Get a feeling of balance in every drawing. One part starts first, other parts follow.

In a tap dance, if the drawing looks good chances are it will work well.

Foot to the beat—hit it hard.

Is ugliness more interesting than beauty?

Drawing by Grim Natwick

(Collection: Suzanne Wilson)

THE SECRET OF ANIMATION IS:

So-called animation effects ultimately come down to the “extreme” drawing. There is no fantastic effect that does not depend on an explicit, convincing single bizarre drawing. (Example: Elephants piling up on each other like cars on a freight train.) This idea is supported by timing and sound effects but it would never be believable without a convincing single extreme drawing which depicts the action exactly.

Animators are nothing less than the master cartoonists of the world whose most amazing creations are hidden in a series of less startling caricatures.

If one took those extremes out of context and held them long enough to examine, the world would be astonished.

There is no reason why a printed book could not have the same impact as animation.

All that is necessary is for the artist to be capable of depicting an animation extreme. No small order.

WHERE IDEAS COME FROM

Ideas come from other people’s vision of life’s truths, when your own ideas of truth clash against them.

Clichés are grist for the humorist’s mill.

If you go to a cliché situation, find ten different ways to play a new version of it. (For example, the singles bar scene has surprise—the unexpected obvious.)

People are overexposed to story today. What are you going to show them that they haven’t seen before?

RESEARCH—Imagine what it would feel like to be the character when the event happens to him. If you have writer’s block, ask yourself why. Maybe you don’t have anything to say.

Paradoxically, ideas can come through the limitations of choosing time, place and genre. Documentary, murder mystery, thriller, and comedy—all suggest their particular elements. In an action adventure the “hero at the mercy of the villain” is a convention of the genre. To fulfill the reversal in an original way is to use the limitations of the genre.

Study genres by watching films to see what they have in common. Read the scripts if possible to find the conventions. Conventions evolved as things that worked. As times change the conventions change. The first film to change the convention is the memorable one.

Do films change society or society change film? The same question refers to advertising. Society changes first obviously.

WAYS OF APPROACHING THE PROBLEM

1. Breaking it into its modular parts.

2. Reversing it. Starting at the goal and working back.

3. Negating it. Stating it as contrary to the way it’s stated—and examining it that way. Problems are in two parts—data and program. One is an encyclopedia; the other is a process.

4. Try translating the parts into other codes or languages to see if the relationships become more obvious.

5. Lining up two ideas (structures) parallel to each other and matching out pieces (frames, voices, characters) from each to form a new pattern.

6. Conceptual Skeleton. A device for creating new ideas by combining two structures.

DISCOVERING USEFUL IMAGES

Images common to all symbolists, science fiction and works of imagination—

1. Complexity—A myriad of objects stuck together, patchwork.

2. Vastness—Vast cliffs, castles, ships, et cetera.

3. Mixed anatomies—Combinations of human with animal with insects, birds and machines.

4. Skeletal variations.

5. Levels—Flying and falling.

6. Esoterica—Mandalas, haloes, fiery objects, lights and lightning.

1. Labyrinths—The city and under the city.

2. Obstructions—Ditches, moats, broken bridges and dead ends.

3. Flying devices—Umbrellas, birds, motor scooters and others.

4. Vertical conveyances—Elevators, conveyor belts and escalators.

5. Horizontal conveyances—Trains, trolleys, and tracks like labyrinths, bridges and tunnels.

More rarely seen images—

1. Animated objects—Houses, mountains, boxes, hoses, ropes, mechanical objects, rocks, trees and flowers.

2. Animated elements—A watery figure, a figure of fire, a wind figure, cloud figures, animated landscapes.

3. Machine combined with an organic form—Such as a flexible space ship, like a plastic manta ray (Soft sets).

4. A place or person which is in opposition to our normal lighting, such as lit from within.

5. A place different in density of atmosphere or gravity.

6. Out-of-place weather phenomena—Hot rain, snow in clear weather, sleet or hail of a different size or color, fog with lightning, unusual wind.

7. Reversed gravity or magnetism of a particular kind.

MORE ON THE CLICHÉ

Clichés are goods to the humorist as grain is to the miller. A cliché is a saying or image with enough insight or truth in it to be worn smooth by constant usage by the unimaginative. It has merit within it. A humorist uses his insight to bring out the aspects of it that simple repetition of it misses. In a cartoon the saying is accompanied by an image (or vice versa) that surprises but is appropriate to its referent.

Every genre of story is a system of clichés. It’s a good system that has “stood the test of time.” All it needs are new ingredients to be enjoyed all over again. Really new—not updated clichés to replace those of yesterday and not mere parodies of reversal.

The clichéd expectations of a jaded audience are a sparkling opportunity for fun and surprise! Set it up—and zizz it in there!

COMEDY: JOKES AND GAGS

Comedy is what happens after “happily ever after.”

A joke absolutely depends on the setting up of a common image complete with all of its conventions, virtues and involvements. Example: Two men go duck hunting. After three days they had not gotten any ducks. “We must be doing something wrong,” one of them says, “Maybe we’re not throwing the dog high enough.”

1. The situation of two men duck hunting sets up the complete conventional image of men in a blind with decoys, calls, costumes, guns and equipment and retrievers. This is the conventional image.

2. The fact of going three days without catching any ducks furthers the conventional image of skillful patience and persistence (Virtue.)

3. “We must be doing something wrong”, brings out the difficulty and technique of the sport and emphasizes the good sense and intellectual aspects of the men. It also sets the listener off (down the garden path) to evaluating the subtleties involved—the blind, the location, the setting up of decoys, et cetera. This is involvement.

4. “Maybe we’re not throwing the dog high enough.” All the credit you gave the men as duck hunters is exploded.

The scene is set, the atmosphere created, relationships sketched and audience involvement brought in. Then, with the audience’s disbelief suspended, it all pops like a balloon.

In a sense, a joke is an act of aggression against the audience: the hearer. Their own mind-set is used against them. There is a strong desire to retaliate—that is, to tell a joke back to the teller (to get even?). Why do people think the experience of hearing a joke is pleasurable? Why is laughter pleasurable?

In review: The teller enjoys superiority by telling. The listener feels superiority to the fictional characters but discomfort at being duped. He wants to “tell another” to get his own back.

Entertainment is the fun of seeing somebody else make mistakes. Comedy is little mistakes and tragedy is big mistakes.

ART ON A SURFACE

Frontality is a primitive way of seeing.

It is the seeing of things.

The forms and shapes are nouns.

The modifications and decorations are adjectives.

It is an object(ive) way of seeing.

Illusionism is a camera way of seeing.

The camera sees a frozen gestalt pattern.

The pattern is a one-eyed two-dimensional code.

The code stands for visual relationships of space, line and form.

It is also an objective way of seeing.

There is a subjective way of seeing.

The artist’s eye is the subject.

The noun-object and its visual relationships are interpreted and shared.

The object and the subject are both seen.

Despite our extrapolations, all three visions are two-dimensional.

The “object” is two-dimensional.

The “space, light and form” is two-dimensional.

The “artist’s eye and interpretation” is two-dimensional.

The most essential aspect of art-on-a-surface is its two-dimensionality.

The expressive but design-fracturing aspects of illusion are brought over into flat design. Tension is created by subordinating a powerful system within the dimensions of a simpler system: three-dimensional into two-dimensional. This demonstrates the scientific idea that systems are understood only through their limits: their limits define them.

WHAT IS ART?

A union of opposites—this is one half a definition, the critical half. The other half is creative—the leaping of the gap.

The critical half may be defined; the creative half must be intuited. We can only talk about the critical half. That is the nature of the two halves…one can be talked about and the other cannot.

In the critical half we can determine if the artwork is a union of opposites.

The opposites are the content. The union is the form. A good work may be strong in content or strong in form. An excellent work is strong in both.

A narrative work of art is a dynamic union of opposites. When one opposite overcomes the other, the narrative is done.

In a pictorial work of art the opposites are united in a dangerous balance of power. Ideally, one more stroke would upset the balance. That is the dynamism of the work.

In a joke or cartoon, opposites coexist in an impossible or absurd union.

Richness in a work of art is based on the quality and quantity of the opposites and the brilliance of the union.

Works of art may be judged by this criterion but not created by it. But they may be corrected by it—with intuition.

Art and Artistry

The fear and anxiety over defining art is the result of critics and artists alike not being able to separate content from technique in discussing art.

There is justifiable anxiety in defining art in any technical terms that would tend to limit expression and create an academy of fixed means. Yet art is expressed through technique of some sort.

Art itself is a complex of ideas: visual, philosophical, emotional and technical, synthesized into the artwork in a living, interacting paradox. Art lives as an organism. It is not a dead singular unit. It reflects the complexity of an individual.

But the technique of art, the means by which the complex of art is made, is another matter. This technique I call artistry. It is not individual as the artist’s vision is individual, but universal as the laws of physics are universal. (This term universal is not to be confused with universal ideas such as love, goodness, truth, et cetera, which are universal abstractions. The universal laws I’m talking about are universal laws of aesthetics—almost in the sense of universal laws of mechanics.)

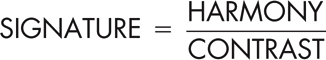

Artistry then, is the manipulation of complements: dark and light, hard and soft, plain and figured, figure and ground, motion and form, et cetera. All these complements can be either harmonious or contrasting—and nothing else.

The artist uses his taste and vision in making the work a complex of harmony and contrast.

Bad art is most often a result of a technical failure in the area of artistry.

1. Too much harmony; too little contrast.

2. Weak unrealized harmony; weak contrast.

3. An unplanned or unrealized scheme of harmony and contrast.

4. Portions of the work not fitting the main scheme of harmony and contrast.

5. Too much contrast breaking up the composition. (Nothing but contrast is impossible because it then becomes all harmony.)

To be a picture doctor, study the troublesome areas in this light.

To deal effectively with harmony and contrast you must know the complements.

Discovery: Shape and Line are complements.

Shape and line combined =

Real physical media (media expressive)

Which in turn is a complement to

Illusion—

Which is made of—

Representation.

• Form and motion are complements.

• Art is subjective / Artistry is objective.

STATEMENT OF THEORY

The Paradox Principle:

The coexistence of complements = the unsolvable riddle = life.

Life is a question. Death is a conclusion.

The play is over when the mystery is solved.

PARADOX I—SURFACE VS. ILLUSION:

Paint vs. Image

Picture Plane vs. Pictorial Space

Dots, Lines, Planes vs. Solids

This is a drawing of “the character.” The character is real but this is not him. This is a drawing of him and his world. To depict “the character” as if you were showing a drawing you did when you were there creates a system within a system.

The artist becomes the narrator. His style says “once upon a time”! That’s why straight illusion is less than satisfying. Since it lacks three of the five senses it can never be “realistic” enough.

STATEMENT OF PARADOX—The more the character looks like a drawing, the more “real” he is.

PARADOX II—BALANCE:

Large vs. Small

Near vs. Far

Dark vs. Light

Object vs. Space

Figure vs. Ground

Dominance vs. Defiance

Harmony vs. Contrast

PARADOX III—COLOR:

Warm vs. Cool

Bright vs. Dull

Dark vs. Light

Broken vs. Flat

Compound vs. Primary

PARADOX IV—DRAWING:

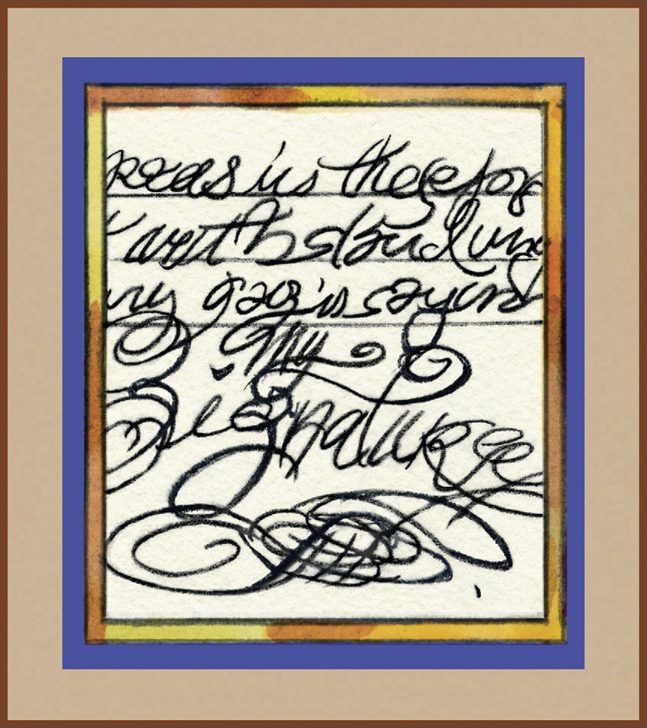

“Signature” vs. Drafting

Organic vs. Geometric

Accuracy vs. Exaggeration

Emotion vs. Reason

Hard vs. Soft

Form vs. Motion

PARADOX V—TONE:

Collage vs. Scene (Illusion)

Silhouette vs. Solid

Positive vs. Negative

Compound Notan vs. Primary Notan (Silhouette)

Flat-Tone Shapes (No Drawing) vs. Broken-Tone Shapes (All Drawing)

THE REMEDY PARADOX—If a thing seems insufficient then subtract some of it. If a thing seems too much, then add to it.

Go to the complement. Dark shows off light. Warm shows off cold. Soft shows off hard. Dull shows off bright.

Prepare for the unheard-of,

Anticipate the impossible,

Imagine the unimaginable,

And sooner than possible.

“What a magnificent ship--what makes it go?”

Originally appeared in Esquire magazine, 1962