CHAPTER 3

NeuroMap: A Brain‐Based Persuasion Theory

In theory, theory and practice are the same. In practice, they are not.

–Albert Einstein

We have spent almost two decades researching how sales and advertising messages affect our brains. This work led to the creation of NeuroMap, the persuasion model you are about to discover. Persuading is not easy and until recently it was considered more an art than a science. By deconstructing the effect of messages on the brain, we have created a simple, yet scientific model to help you develop and deploy persuasive messages targeting anyone, anywhere and anytime. Using NeuroMap will make all your attempts to persuade more successful and less risky. So how widespread is the use of persuasion models in advertising to begin with? You would expect that companies that spend millions of dollars would always use scientifically based persuasion models to guide the creation of their campaigns. Well, most don't.

Recently, I decided to thoroughly research the effect of public health messages and propaganda campaigns on adolescents [49]. Each year, hundreds of millions of dollars are spent to warn us that smoking is dangerous, drugs can kill, or texting and driving is not just an imprudent behavior but dangerous. What I found (sadly) is that most of the public service announcements (PSA) campaigns do not use persuasion models to guide their creative development process and hardly any use brain‐based models. According to a meta‐analysis conducted by Whitney Randolph (the only one we can find!), less than one‐third of empirical articles on PSA report using any persuasion theory at all [50]. From our experience dealing with many Fortune 500 companies, this trend is not specific to PSA campaigns; it appears to be the norm among most advertising campaigns. I believe that is why such a large majority of advertising campaigns fail. So let's clarify what a persuasion theory is and why it matters to use one to save time and money.

POPULAR PERSUASION THEORIES

A persuasion theory is a model that can explain and predict the probability messages have to influence or convince. Presumably, good persuasion models help creators of messages be more systematic in the way they approach the development of a narrative to convince. Reviewing popular persuasion theories can be confusing. There are several models that have been cited for decades, yet there is little evidence that any are effective. The differences between the most popular models highlight the challenges faced by researchers to deconstruct the critical processes involved in explaining and predicting the effects of persuasion. Although the following brief review explains why there is often confusion and discord among persuasion researchers, it also shows that emerging neurocognitive models offer the best hope for creating and testing radically more powerful advertising messages.

Here are summary descriptions of the most popular persuasion models of the past two decades. You may be familiar with a few of them, but usually, only academics or persuasion researchers have heard of them.

The Elaboration Likelihood Model

Inspired by the cognitive theoretical movement, this model [51] states that a persuasive message will trigger a logical succession of mental processes that engage either a central (cognitive) or peripheral (emotional) route. Both routes represent the levels of thinking performed by recipients to understand the meaning of the information. The central route ensures that the message is considered further (or elaborated), in which case the message has achieved its persuasive intent. However, if a message is processed by the peripheral route, the effect is predicted to be mild. According to the Elaboration Likelihood Model, a good message is only elaborated if it appeals at a deep and personal level. Advocates of the Elaboration Likelihood Model argue that an effective campaign must include strong proofs to establish the credibility of the claims used in a persuasive message. However, despite its wide popularity, the critical flaw of the Elaboration Likelihood Model is to assert that persuasion is possible if recipients only engage cognitively with the content of a message, a fact that is not supported by NeuroMap and by most neuromarketing research studies of the past decade.

The Psychological Reactance Theory

According to this theory, humans are deeply motivated by the desire to hold themselves accountable and free from other's rules and suggestions [52]. The psychological reactance theory predicts that if people believe that their freedom to choose how they want to conduct their lives is under attack or manipulated, they will experience an ardent desire to react as a way to remove the pressure. Reactance is believed to be at its peak during adolescence because teens have a strong drive toward independence and form beliefs and attitudes that often compete with those recommended by their parents. This model further predicts that explicit persuasive messages trigger more resistance than implicit attempts. Also, Grandpre [53] demonstrated that reactance to persuasive messages increases with age. This may further explain why campaigns invoking the role of parents discussing the dangers of smoking are not effective [54]. The major flaw of the model, however, is the suggestion that persuasive messages are always recognized consciously, a fact that is clearly no longer defendable based on the evidence generated by neuromarketing studies.

The Message Framing Approach

This model is based on the notion that a persuasive message can be framed in two ways: either a loss if recipients fail to act/buy or a gain if recipients agree to act/buy [55]. Loss‐framed messages are typically effective when they raise consciousness on the risks or loss associated with a lack of action. For instance, you may kill people by texting and driving, or you may be financially ruined if your house is destroyed by a fire and you have no insurance. Experiments using this approach have demonstrated that loss‐framed messages are better at preventing risky behaviors than changing them, suggesting that the effect may only be short‐term [56–58]. Our research also shows that loss‐framed messages work better than gain‐framed messages because of the role played by the primal brain.

The Limited Capacity Model of Mediated Message Processing

The Limited Capacity Model is another model inspired by the field of cognitive psychology. It provides a conceptual framework based on a series of empirical studies examining the relative effect of message elements on key cognitive functions such as encoding, storage, retrieval, information processing, and limited capacity [59]. The model suggests that allocation of brain resources may be equally distributed among several cognitive subprocesses leading to inconsistent results in recall and general effect on recipients. Studies using the Limited Capacity Model indicate that adolescents remember more details from public service announcements than college students do and require more speed in narratives to stay engaged. This model did confirm that key cognitive differences exist between adolescents and adults and that these differences may alter the subprocesses involved in processing persuasive campaigns [60]. However, it lacks scientific credibility and is largely ignored by the persuasion scientists today.

Kahneman's Two‐Brain Model

The dual processing theory was originally introduced by Stanovich and West [61], and is also known as the System 1 and System 2 theory. It was eventually popularized by Daniel Kahneman through his seminal book Thinking, Fast and Slow [62], for which he received the Nobel prize in economics. The tenets of this approach are both simple and profound. Although the research supporting this model was done to study rationality and explain cognitive processes in a multitude of decision‐making tasks, the value of the theoretical framework extends far beyond cognitive psychology. In fact, it speaks directly to the nature of human cognitive biases and how they affect our day‐to‐day choices. For Kahneman, humans regularly access two decision systems that have different if not opposing priorities. System 1 is the most primitive part of the brain. It is automatic, unconscious, and requires low computational resources. System 2 is the newest part of our brain. It is more intentional, needs more consciousness, and has access to more cognitive resources to establish goals and calculate consequences of our decisions. Kahneman argues that System 1 rules over most of our decisions (Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1 Thinking, fast and slow.

SALESBRAIN'S MODEL OF PRIMAL DOMINANCE: NEUROMAP

NeuroMap expands the dual system model in profound ways (see Figure 3.2). First, we recognize that even though anatomical borders of each system are the subject of ongoing discord among neuroscientists, they have gained wide acceptance among members of the neuromarketing community. At SalesBrain, we call System 1 the primal brain and System 2 the rational brain, but we consider that the primal brain not only rules our decisions, it dominates the persuasive process. There are key differences between the primal and rational brains we have already introduced but need to reemphasize.

Figure 3.2 The primal and rational brains.

Source: SalesBrain. Copyright 2012–2018.

The primal brain only “lives” in the present because the notion of time is too abstract for a survival‐centric brain. Also, it is much older in terms of evolution, but it can process information at remarkable speed because your life depends on it! We are not conscious of what the primal brain does most of the time. For example, we do not think about our breath, even though we can, but for the most part, it just happens. It is all regulated below our level of consciousness. So, the primal brain cannot think much, it certainly does not read, write, or perform arithmetic. It is guided primarily by vigilance, intuition, and senses that guide our short‐term actions. Because it is the fastest brain to respond and it oversees our survival, we believe that the primal brain also dominates the persuasive effect. The default processing style of the primal brain is instinctive, intuitive, and preverbal. Unfortunately, most persuasive messages are seeking to motivate people to make long‐term decisions and use text to convince; therefore, they are not primal brain friendly!

Meanwhile, the rational brain is much younger, much slower, and does have the capacity to think, read, write, and do complex math to predict, assess risk, and engage in long‐term goal setting. The rational brain can travel through time. Although memory is a highly distributed system, critical circuits of the rational brain allow us to file, organize, and retrieve information over a considerable amount of time. With the help of our frontal lobes, we also project a lot of our attention and thinking in the future. In fact, you could argue that few of us truly live in the present because we get lost in our worries of the past or the future. Thankfully, we do have some level of consciousness because of the rational brain; we can reflect on our experiences and even share them with others. That gives us more ability to control the rational brain than the primal brain.

NeuroMap: The Bottom‐Up Effect of Persuasion

When we first published our persuasion model in 2002, we suggested that the reptilian complex was the ultimate decision maker. The model was radical, if not controversial. At the time, we did not have as much scientific evidence to support the theory as we do today. Indeed, the research and case studies we have accumulated since 2002 confirm that persuasive messages do not work unless they first influence the primal brain – that is, System 1 [14]. In fact, the primal brain is largely influenced by the reptilian complex, a system composed of the brainstem and the cerebellum. NeuroMap is based on the dominance of the primal brain over the rational brain. NeuroMap predicts that when a message is friendly to the primal brain, it will quickly radiate to the upper sections of the brain where the information will be elaborated using critical thinking and logic. In short, NeuroMap supports the dual processing model proposed by Kahneman and his argument that System 1 rules, but also provides enhancements that can be directly applied to a persuasion model. Indeed, we have convincingly identified that successful persuasive messages capture the primal brain first and convince the rational brain second. We call this the bottom‐up effect of persuasion. Both conditions are necessary for a message to work on the brain! In our view, the reason why so many persuasive messages fail is because they do not trigger the bottom‐up effect. Worse, they try to appeal first and foremost to the rational brain.

Here is an example of an ad for an insurance product (Figure 3.3). Because text cannot be processed by the primal brain, it can only be processed by spending much cognitive effort. Because the rational brain does not control the initial flow of cognitive energy, the message will be quickly discarded.

Figure 3.3 Rational message.

Instead, this next message has far better chance to trigger a primal brain response. As provocative or shocking as this next message may be (Figure 3.4), it does recruit attention and activates the bottom‐up effect. We do not really want to think about the value or importance of getting life insurance. However, once reminded that we could die quickly, we do.

Figure 3.4 Primal Brain Friendly message.

Proving the Dominance of the Primal Brain

Here are other ways by which we can quickly demonstrate the ongoing dominance of the primal brain. For instance, try to solve the equation shown in Figure 3.5 quickly: How much is the candy if the cookie costs one dollar more than the candy?

Figure 3.5 Candy equation.

The answer is 5 cents, not 10 cents! It seems so weird that you and over 95% of people we have tested on this question fail to solve a seemingly easy math equation. However, the error can be explained by the dominance of the intuitive and fast nature of the primal brain, which made you jump to the wrong conclusion. Here is another test demonstrating primal dominance (Figure 3.6). Which bet would you favor?

Figure 3.6 Gain maximization bet.

Most people pick option 2, a more attractive positive outcome created by using the number 100%. This option “frames” a perception of choosing the option with the highest probability of gain, even though both options have the same mathematical gain expectancy.

However, notice how you feel about the next two options now. Which one would you pick (Figure 3.7)?

Figure 3.7 Loss‐avoidance bet.

You probably picked 1, and you most likely did so faster than when you evaluated the two options of the first bet. Option 2 frames the perception that you will lose $500 for sure, whereas option 1 creates the perception that you may still have a chance not to lose anything at all. When facing such options, the primal brain instantly activates a loss‐avoidance bias, a bias that is central to most of our buying decisions.

The loss‐aversion bias was first discovered by Kahneman and Tversky. In fact, some researchers even quantified the loss‐aversion bias at 2.3 times the value of winning. This means that if you lose $1, it takes winning $2.3 to offset it. Note that this explains why it is always hard to sell something: the negative emotion your customers will experience to pay $1 for anything can only be overcome by the positive emotion generated by receiving something they would perceive as being worth at least $2.3. This also explains why offering a 50% discount is so effective: it compensates for the 2.3 loss aversion bias. Meanwhile, many other so‐called cognitive biases can be explained by NeuroMap.

Cognitive Biases Explained by NeuroMap. A cognitive bias can be defined as a predictable pattern of deviation from logical reasoning. Cognitive biases prevent us from making systemic and completely rational decisions. Psychologists have studied the nature of these biases for centuries, and most recently Buster Benson, a software engineer with a passion for decoding human behavior proposed an interesting nomenclature of 188 such biases [63]. Many social biases, for instance, preserve our self‐esteem and stem from our ego‐centrism [64–66]. A full discussion of this topic is beyond the scope of the book. However, we believe that many of these biases can be explained by the dominance of the primal brain over the rational brain: if all our behaviors were rational, these biases would not exist.

Error Management Theory and Cognitive Biases

Psychologists Martie Haselton and Danie Nettle [67] proposed a very powerful model to integrate most cognitive biases based on the theory of evolution called the error management theory (EMT). According to EMT, we collectively suffer from “paranoid optimism” a dynamic tension that pushes us on one end to “play safe” and on another to “seek risk.” The paradoxical nature of this tension is a function of our drive to survive. For instance, men tend to overestimate how much women desire them. Haselton and Nettle argue that this tendency may have been reinforced over thousands of years to increase the number of sexual opportunities, and therefore increase the number of children from one pool of genes. They also argue that decision‐making adaptations have evolved to make us “commit predictable errors.” They posit that EMT predicts that human psychology contains evolved “decision rules that are biased toward committing one type of error over another.”

NeuroMap can also explain and predict the same biases. The dominance of the primal brain is crucial during events that compromise our survival. In the absence of enough cognitive energy and the required need to act quickly, we activate programs that minimize risk. Now let's go back to the tendency to be overly optimistic. This does not easily reconcile with the drive to avoid risk. For instance, people tend to be overly optimistic about health problems they face [68]. In that case, EMT states that we have more sensitivity to harms that may arise from external sources (others) than harms that can come from internal sources (us). This suggests that we have different biases based on the origin of the risk. Once again, this is predicted by NeuroMap. External threats are urgent for the primal brain to process and trigger our instinctive response to avoid risk and uncertainty. However, internal threats are typically more complex to assess and therefore are more likely to engage cognitive resources from the rational brain, which may be more naturally inclined toward optimism and hope. Haselton and Nettle call this phenomena “paranoid optimism.” They observe that we appear fear‐centered about the environment (primal) but optimistic about the self (rational).

Top Cognitive Biases

We summarize next some of the top cognitive biases that have been popularized by successful thought leaders and authors like Malcom Gladwell, Dan Ariely, and Buster Benson.

The Bias of Thin‐slicing

Malcolm Gladwell's book Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking [69] tells curious stories in which people make seemingly absurd decisions using a limited amount of information. He calls this bias “thin‐slicing” and draws examples from a wide range of situations involving scientists, doctors, executives, art experts, and more. In all these cases, logic and rationality are missing. Choices are made in the “blink of an eye” even though they may involve smart and educated decision makers. Although Gladwell does not investigate the neuroscience of “thin‐slicing,” NeuroMap can explain many of the situations he describes. For instance, in the presence of too much information, the primal brain takes over while the rational brain stalls. Furthermore, when our primal brain dominates plenty of emotional factors influence our decisions beyond our level of consciousness. Although there are clear benefits from allowing the primal brain to control an enormous number of our decisions, it can lead us to make very bad choices. Remember the example of trying to find how much the candy was worth? Your primal brain took over, and most likely you did not get the right answer!

Another important book discussing the faulty nature of many of our decisions is Predictably Irrational by Daniel Ariely [70]. The book presents several cognitive biases that affect many of our decisions, basically because the primal brain controls the process below our level of awareness. Following are a few cognitive biases.

The Bias of Relativity

To decide, we need to be able to contrast options that appear radically different. By offering two options that are about the same, and a third that is radically different, most people will choose the third. The primal brain is wired to make quick decisions, and contrast allows that level of efficiency. When we easily compare and contrast options, we are allowing the dominance of the primal brain to rule our choices.

The Bias of Anchoring

Our first decisions may considerably influence the rest of the decisions we make regarding the same product or solution. This suggests that we are wired to repeat decisions we find satisfying. That is why habits are so addictive. We argue the reason we do that is because the primal brain wants to reduce cognitive effort by retrieving old patterns of behavior. It also explains why it is so difficult to change our behavior in general or shift to another brand of toothpaste!

The Bias of Zero Cost

We always prefer free options over fee options because we perceive that there is no risk when the item has no price. According to Ariely, the reason free shipping offers are so effective is that it lifts the objection of adding any cost on top of the price of an item. In fact, the zero‐cost bias reflects the loss‐avoidance bias of the primal brain. It is not logical and rational to wait in line for a free ice cream, yet thousands of people do it because they are under the dominance of their primal brain, which seeks instant gratification!

The Bias of Social Norms

We act based on what is expected of our community of reference (social norm), and this may influence the way we respond to market offers. If the offer is aligned with the social norm, we accept the offer. If it is not, we reject it. What this explains is that incongruence between our primal brain (compliance reduces risk or regret) and the rational brain (evaluation of a market offer) disrupts the bottom‐up effect. NeuroMap predicts that for messages/offers to work, they must stimulate both the primal and the rational brains.

The Bias of Multiplying Options

According to Ariely, we pretend that we prefer more options than fewer. Paradoxically, to survive, we are better off reviewing a limited number of options. We will discuss this bias when we elaborate on contrastable as a persuasion stimulus later in this chapter. We argue that the primal brain hates too many choices. The rational brain does not mind going through an extensive evaluation process, but it may delay decisions in the process. This creates a paradox in many of our decisions. We tend to say we want options, but at a deeper level, we do not want to face the cognitive burden of choosing among many. NeuroMap posits that a persuasive message can trigger decisions when it asserts that there is only one good decision: the one you suggest!

The Bias of Expectations

What we expect influences our behavior. This bias is the direct consequence of the dominance of the primal brain over the rational brain. What we want is known to emerge in primal subcortical areas of the brain. What we want shapes what we expect, and what we expect does overrule what we logically and rationally report we need.

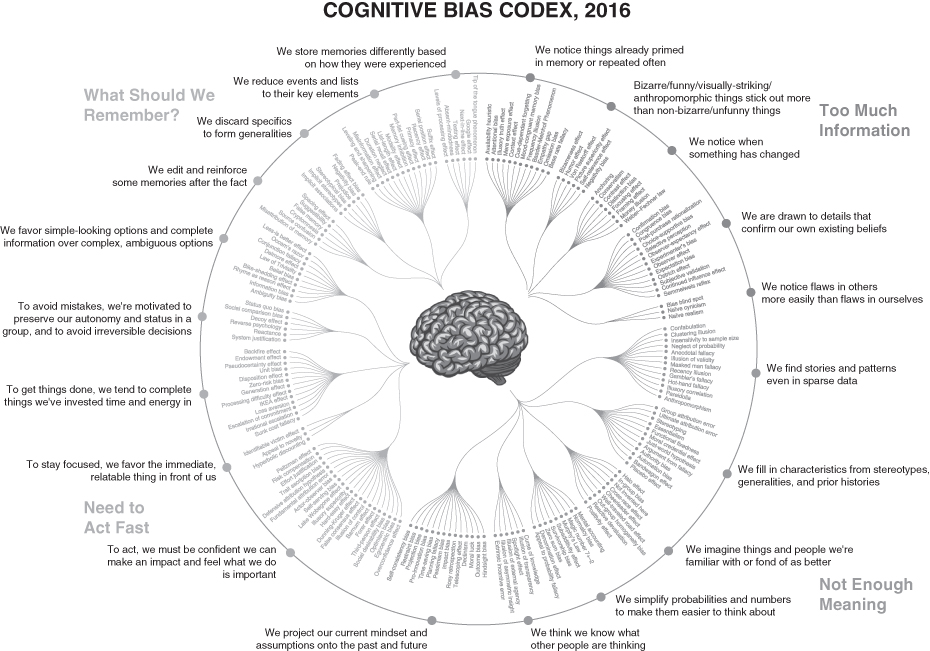

The Cognitive Bias Codex

Completing an inventory of the most common cognitive biases is challenging. Academics have not agreed on key definitions, so the topic remains the subject of heated debates. In 2016, however, Buster Benson, a software engineer with a passion for decoding human behavior proposed an interesting nomenclature of 188 biases [63]. The result of his work is one visual you can see in Figure 3.8. The picture does not do it justice, so I recommend you visit the website, which you can easily find by searching Cognitive Bias Codex.

Figure 3.8 Cognitive Bias Codex.

Source: Used by permission from Buster Benson.

Even though Benson's work is arguably exploratory in nature, we find it impressive. More important, NeuroMap can explain and predict all categories of the cognitive biases that are identified by the model. They are as follows:

- Too much information: The dominance of the primal brain is based on survival priorities that are deeply anchored in our biology. Cognition came later. We are not wired to process a lot of information, spend ample time finding patterns, or agonize over decisions. Too much information freezes the primal brain.

- Not enough meaning: Our primal brain does not have the cognitive resources to compute and resolve complex arrays of data. If the pattern of a situation is completely new, and not urgent or relevant, the primal brain will not be able to retrieve a previously stored set of commands that would accelerate the processing of the information. We love cognitive fluency because it conserves valuable energy.

- Not enough time: Time is directly related to how much energy the brain needs to process information. In the primal brain, faster is always better. Therefore, situations that require time do not appeal to our older brain structures and receive low priority.

- Not enough memory: Our brain is not designed to store much information. The reason is simple. Encoding is costly, because of the energy required to store but also to maintain and retrieve our memories. Recent research demonstrates that memorizing attaches specific neurons to our memories. In fact, by using light to stimulate nerve connections, Dr. Malinow and his team successfully removed and reactivated memories by stimulating synapses in rats' brains [71]. This only proves further that the brain welcomes situations or events that make it easy to hold information in working memory and not highly dependent on long‐term encoding. The primal brain favors such conditions over others.

To conclude, NeuroMap provides a simple yet practical model for developing and deploying persuasive messages: it helps you consider cognitive biases by following a linear creative development process. It is designed as a sequence of steps to maximize the impact of your persuasive arguments. Igniting the primal brain requires using only six stimuli in the brain. The six stimuli will provide you with simple guidelines for the creation of any persuasive message. The value of the six stimuli model is now supported by nearly 20 years of scientific and empirical evidence.

WHAT TO REMEMBER

- Persuasion has been studied for decades, but old models have ignored for too long the dramatic role played by subconscious brain structures.

- Persuasion is a bottom‐up effect between two main brain systems named the primal and rational brains.

- NeuroMap shows that persuasive messages do not work unless they first and foremost influence the bottom section of the brain – the primal brain, which reacts to emotional, visual, and tangible stimuli (see Chapter 4) and can amplify or abort any persuasive attempt.

- Once a message has “engaged” the primal brain, persuasion radiates to the upper section of the brain where we tend to process the information more sequentially and confirm decisions in the frontal lobes.

- Most of the 188 cognitive biases can be easily explained and predicted by NeuroMap.