CHAPTER 4

Applying Six Stimuli to Persuade the Primal Brain

Some balance of the emotional and rational systems is needed, and that balance may already be optimized by natural selection in human brains.

–David Eagleman, neuroscientist and author

We learned in Chapter 3 that persuasion can be explained and predicted from the quality of messages that appeal to the primal brain. Table 4.1 will help you make the transition from the science of NeuroMap to its practical application. Although we recognize the value of identifying 188 cognitive biases [63], we believe there is a limited number of meta‐biases (biases above other biases) that can explain and predict why we are so irrational in our choices. We have identified six primal meta‐biases that mediate the way persuasive messages work on the brain. These meta‐biases can all be explained by the dominance of the primal brain. The term stimulus means a detectable change in the environment that will elicit a predictable response from the primal brain of your audience. We suggest that, together, the six stimuli (Figure 4.1) work as a system of communication you can use to influence the primal brain.

Table 4.1 Primal biases.

| Primal Stimulus | Primal Bias | Primal Goal |

| Personal | To survive | Protect from threats |

| Contrastable | To speed up | Accelerate decisions |

| Tangible | To simplify | Reduce cognitive effort |

| Memorable | To store less | Remember limited information |

| Visual | To see | Rely on the dominant sensory channel |

| Emotional | To sense | Let neurochemicals guide action |

Figure 4.1 Six stimuli.

That is why we call it a language. This analogy is important because it points to the value of using all six stimuli to maximize the persuasive power of your messages. After all, when you learn to speak a foreign language, using just verbs will not take you far in a conversation. Another way to understand NeuroMap is to consider the six stimuli as a creative checklist that has already been used successfully by thousands of persuaders over the past 16 years.

Now, let's explore each stimulus in more details.

PERSONAL

“Let's try to teach generosity and altruism, because we are born selfish.”

– Richard Dawkins, Evolutionary biologist and author of The Selfish Gene

The first stimulus to activate the primal brain is to make sure your message centers fully on the person or group you are trying to persuade. Because the primal brain is driven to help us survive, humans are fundamentally wired to be self‐centered and to attend first to what affects us personally. Jaak Panksepp, a neurobiologist who has studied the emotions of animals extensively, argues that “the utility of selfishness has promoted the evolution of many self‐serving behaviors” [39].

The primal brain evolved over millions of years. As such, it still rules our most primitive, survival‐centric behavior. The primal brain is the oldest structure of our nervous system, and some parts are believed to be nearly 500 million years old. Although the primal brain is ancient and rather small (about 20% of the mass of the entire brain), it remains largely in control of all the functions that are critical to our life like respiration, digestion, and automated motor commands – essentially all the functions that are regulated by the autonomic nervous system. The primal brain also produces a multitude of key neurotransmitters like serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine, all part of a special group of molecules called monoamines. Monoamines are chemical messengers that form the basis of how networks of neurons fire and wire during brain activity. Because they influence so many affective responses, they have been intensively studied for decades. Each neurotransmitter has its complex network linking older regions of the brain (primal) with newer ones (rational).

In a brilliant paper discussing how hard‐wired selfishness and altruism crosses, evolutionary psychologist Gerald Cory [72] suggests the existence of a dominant “self‐preservation” program that can explain our tendency to seek power, attack, and express less empathy for others. His approach is inspired by the triune theory of Paul McLean [73]. Although many neuroscientists contest the triune theory, it has the merit of suggesting the existence of three main brain structures that evolved over a considerable amount of time. McLean first coined the term reptilian complex to describe the function of a group of brain structures that is mostly involved in regulating critical survival functions like breathing, eating, and sexual reproduction. He suggested that the limbic system, which hosts many important networks involved in emotional processing, developed when the earliest mammals appeared and, therefore, called it the paleomammalian complex. Finally, McLean observed that the uppermost layer of the brain, which enables the highest cognitive abilities like thinking, planning, predicting is found in all mammals' brains but, more importantly, is especially large in the human brain. He called that layer the neomammalian complex.

The reason that the McLean model has been largely abandoned is that we know now that older brain structures like the basal ganglia (considered part of the limbic system) are not only found in reptiles but also in the earliest jawed fish. We also know that the earliest mammals had neocortices and presumably some ability to use higher cognitive functions as well. Finally, and more importantly, the three layers do not operate independently from each other. However, taking all that into account, the evolutionary nature of our brain development is a biological reality that was well‐captured by the McLean model, and it is continuing to influence important psychological theories such as the Triune Ethics Model.

The Triune Ethics Model

Davide Narvaez [74] developed a theory of ethics based on the McLean model, which is appropriately labeled the Triune Ethics Theory. It is a psychological theory based on the neurobiological roots of our multiple moralities. The Triune Ethics Theory suggests that there are three types of moral orientations that have evolved over millions of years: the ethic of security, the ethic of engagement, and the ethic of imagination. The ethic of security is based on the critical urgency of attending to any threat and is driven by the dominance of primitive systems hardwired into our primal brain. Therefore, fear and anger urge us to feel safe and practice self‐centeredness. Narvaez confirms that the primal brain is very self‐focused. It seeks routines and avoids novelty, a view that explains the importance of making messages personal to grab attention. Gerald Cory, another acclaimed psychologist who spent his lifetime investigating the role of evolution also asserts that we are under the influence of critical survival and emotional forces that we cannot consciously control [75]. He further states that from “the predominantly survival‐centered promptings of the ancestral protoreptilian tissues, as elaborated in the human brain, arise the motivational source for egoistic, surviving, self‐interested subjective experience and behaviors.”

Meanwhile, this discussion on personal would not be complete unless we highlight the seminal contribution of Freud to the topic of ego dominance in our daily behavior.

Freud's Psychoanalytical Model

For Sigmund Freud [76], the basic nature of humans was instinctual (primal), largely controlled by innate forces that act below our level of consciousness. He established that our core instincts are sexuality and aggression. Instincts are automatically activated when we experience an unpleasant tension. In his psychoanalytical model, the sexual instinct ranges from pure erotic pleasure to satisfying thirst or hunger, whereas the instinct of aggression refers to the destructive need to return to a state of nonexistence, a concept that he simply labeled the death instinct. According to Freud, drive reduction brings the body back into a natural state of homeostasis.

For Freud, the price we pay to live in a civilized society is to feel and hold a permanent psychological tension [77]. According to him, all behavior has underlying psychological causes, an idea that he called psychic determinism. He proposed a structural model of personality based on our ability to manage our psychic energy, which consisted of the id, the ego, and the superego [78] (Figure 4.2).

The id is present at birth and is entirely unconscious during our entire lifetime. It controls the total supply of our psychic energy and transforms basic biological drives into pain avoiding psychological tensions. The id is also called the primary process and can be described as the biological component of personality. We would argue that the influence exerted by the id reflects the dominance of the primal brain on our behavior. The ego develops out of the id by the time a child is eight months old. In Freud's terms, the ego is “a kind of facade of the id, like an external, cortical, layer of it.”

Figure 4.2 The id, the ego and super ego (1933 Illustration by Freud).

Even though the model presented by Freud is over 100 years old, it is still regarded by many psychologists and psychiatrists as the most important building block to understanding human behavior. It focuses on the predominant role of the unconscious, what we consider to be the direct influence of the primal brain. Since Freud was a highly regarded neuroscientist during his time, it is not completely surprising that even contemporary neuroscientists have taken a special interest in his model. In 2008, Mark Solms conducted an interview for the magazine Mind in which he discussed Freud with Erik Kandel of Columbia University [79] (2000 Nobel laureate in physiology), who confirmed that one of Freud's biggest contributions is the suggestion that the same unconscious mechanisms are at play in a healthy mind as they are with someone struggling with a mental disorder. Kandel also claimed that psychoanalysis is “still the most coherent and intellectually satisfying view of the mind” [80]. Like Kandel, Mark Solms also believes it is possible to link specific brain areas to the three components of personality defined by Freud: the id, the ego, and superego. The instinctual id maps nicely to the primal brain, whereas the emotional ego is best associated with the higher limbic structures and the posterior sensory‐centric part of the cortex (both considered part of the rational brain).

Although many of us struggle with the idea that selfishness may drive so much of our behavior and is one of the key drivers of our decisions, for Richard Dawkins [81], the most plausible answer to this puzzling question is in our genes. In his famous book The Selfish Gene, Dawkins convincingly presented a gene‐centered view of evolution that has continued to rock the scientific community since the book was first published over 40 years ago. Dawkins wrote, “genes are in a sense immortal…our basic expectation by the orthodox, neo‐Darwinian theory of evolution is that genes will be selfish.”

Applying the Personal Stimulus to Persuasive Messages

There are two ways to make your message more personal and, in doing so, more persuasive:

Focus on Your Audience First. Make sure you put your audience, prospect, or listeners at the center of the message. So many ads or presentations forget this simple rule. Admit it: Have you not ever started a presentation by saying, “Good morning, ladies and gentlemen. Today I would like to tell you about our company, our values, our mission statement, our technology…”? The image in Figure 4.3 is indicative of just how interested and excited the primal brains of your audience will be while listening to your introduction.

Figure 4.3 Man sleeping during pitch.

In a matter of a few seconds, you only prove that you have no intention of putting your audience at the center of the story because it is all about you instead of them!

According to Kahneman [82], we experience 20,000 psychological “present” moments per day, each three seconds long. Since the primal brain craves input that is personal, a substantial portion of these moments is spent thinking about us!

Focus on a Pain That Is Relevant to Your Audience. Our primal brain seeks to protect us. Therefore, in your attempts to persuade, highlight, if not magnify, a threat, a risk, or a pitfall that your solution can solve. As a result, you will command immediate attention. Too often, messages focus on the solution (business centered) and not the problem (personal). NeuroMap suggests that before offering a solution, you need to remind your audience of a pain they have experienced or do not want to face. This is not to manipulate or create undue stress. It is simply to recognize that the primal brain will not dedicate energy unless your message is both urgent and relevant to the person you are trying to engage.

The Neuroscience of Personal

Since there are no studies testing the neurophysiological effect of making a message more personal, we decided to create our own. We recruited 30 participants, half males, half females with an average age of 33 years old. We collected data from their skin (GSR), their hearts (ECG), their faces (facial coding), their cortex (EEG), and their eyes (eye tracking). The neurophysiological variables helped us measure how much each persuasive stimulus (a total of 12) sustained visual attention, triggered emotions, produced cognitive effort, cognitive distraction, and cognitive engagement. The experimental design is presented in Figure 4.4.

Figure 4.4 SalesBrain's neuro study.

For personal, we tested the following research question:

Can making an ad more personal improve its persuasive effect on the primal brain?

We used the following advertising stimuli to test our hypothesis:

- Video footage of people flying a wing suit. The video was filmed from two perspectives:

- Personal (objective) perspective: watching this footage makes the viewer see the landscape as if he/she was flying in a wing suit.

- Impersonal (subjective) perspective: viewer is observing others jump and fly in a wing suit.

- Fishing Print Ads

- A first ad featured a fishing boat and promoted business‐centric claims, like the boat is safe, comfortable, and so forth.

- A second ad featured someone catching a big fish and highlighted customer‐centric claims like the joy of bringing a fish home.

The results supported the hypothesis:

- The personal video segments making the viewer experience flying in a wing suit triggered much more attention (+14%) and more emotional arousal (+25%), as well as more negative emotions (+143%) than the video segments giving a more impersonal experience of the flight.

- The ad featuring someone catching a fish triggered much more attention (+39%), far more arousal (+520%), more positive emotions as well as more cognitive engagement (+52%) than the ad focusing on the fishing boat. It also captured more visual attention in critical areas of interest.

Personal Neuroinsights: Raise the impact on the primal brain by making your message personal. When putting your customers at the center of the narrative, you can quickly transport your audience in the story of your value proposition.

What to Remember About Personal

- We are wired to be selfish.

- Perceiving something as personal makes us proactively scan our environment for what is relevant and urgent to us.

- If you cannot magnify a pain that matters to the members of your audience, you will not grab their attention.

CONTRASTABLE

“We are so constituted that we can gain intense pleasure only from the contrast, and only very little from the condition itself.”

– Sigmund Freud, neurologist and founder of psychoanalysis

The priority of the primal brain is to accelerate decisions, and we do that best when we have limited options. This points to an important paradox in consumer behavior: customers tend to tell you they want lots of brand options, even though they subconsciously resist using valuable energy to evaluate and sort the best ones. I did not discover this paradox by practicing conventional marketing. Rather, I detected this puzzling contradiction nearly 20 years ago by observing shoppers in grocery stores. At the time, I was the vice president of marketing of a grocery chain called Grocery Outlet. Grocery Outlet sold top brands at bargain prices in 12 US states. Our products' variety was somewhat limited given the nature of our retail concept, so I wanted to know if we could increase our sales by adding additional brands for certain categories of products. I conducted focus groups, and sure enough, when I asked customers if they wanted more choices, they always said yes. However, when I observed them shopping in the stores, they systematically froze in front of too many possible choices. When faced with too many options that were not immediately contrastable with one another, customers were unable to quickly and easily differentiate among assorted brands. This explained why our category sales did not move quickly when we added brands. Customers were overwhelmed by being in front of so many options.

That is the paradox of choice. It is also the title of an excellent book by Dr. Barry Schwartz [83], in which Schwartz demonstrates that we do not get happier from getting more choices, and therefore we subconsciously seek to have fewer options. Even though we may complain when we have limited choice, this response is a function of the thinking routine of our rational brain. After all, it is logical to assume that in the presence of more choices, we have a greater probability of finding what we want. However, since the primal brain dominates our decision‐making process, we want to avoid at all cost the time, energy, and risk of a lengthy decision cycle, which is what more choices will bring.

Schwartz's book cites many studies proving the bias for our preference to have limited choices. For instance, a study performed in a gourmet store featuring 24 varieties of jam in one experimental condition and only six in another demonstrated that presenting fewer varieties could increase sales tenfold [84]. Meanwhile, according to renowned Yale medical doctor Jay Katz [85], we choose to outsource many of our decisions in order to escape the burden of making decisions, even when our lives are at stake. According to Katz's research, a majority of patients prefer others to make decisions about their care, rather than making their own choices. We recommend the contrastable stimulus to push customers toward a simple and obvious choice: the best solution to their pain!

The Use of Contrastable Offers in Comparative Advertising

The most common use of contrastable in advertising is comparative advertising, where one brand compares itself to another. There are many research papers on the effect of comparative advertising, but few make any reference to consumer neuroscience and none provide a brain‐based interpretation of its results. According to Professor Fred Beard, a general conclusion we can draw, though, is that comparative advertising works! – especially for “products of high quality,” where claims are well substantiated and focused on salient benefits that are believable [86]. Beard explains that comparative advertising works especially well for companies that have a smaller market share. This makes perfect sense! How can you convince anyone to buy your product unless you do the challenging work of finding what your unique differentiators are first?

Although infomercials have a less than positive reputation because consumers often say they do not like them, this unique format of advertising has a remarkable effect on us. Infomercials work on the primal brain because they use customer stories to present evidence of a sharp before‐and‐after contrast. For instance, they typically feature individuals with serious problems (such as being overweight or having acne) who went through a radical transformation thanks to a “miraculous” product. There are very few studies on the effect of infomercials because formats and products vary greatly. However, one experiment conducted by a group of researchers from Southern Illinois University [87] managed to provide clarity on why infomercials work so well. They decided to create messages formatted in three ways: an advertising (aspirational) message, an infomercial, and a direct experience. The researchers hypothesized that the level of credibility gained by viewing or experiencing these three different formats would follow a continuum from low credibility (advertising message), to medium credibility (infomercial) to the highest credibility (direct product experience). Presumably, direct experience would have the highest level of credibility because people tend to believe and remember more what they do than what they see. The results support what we would predict with NeuroMap. The superiority of infomercials over regular television ads was striking. In fact, infomercials' scores placed them very close to the direct experience format. Furthermore, the more infomercials used contrast between the pain of the products they solved and the solution, the more effective they were. The contrastable stimulus acts as a catalyst for consumer decisions, and if the success stories shared are credible, it pushes the primal brain to decide in seconds.

Applying Contrastable to Persuasive Messages?

There are easy and practical ways to make your message more contrastable: increase the saliency or prominence of your benefits and compare them against other brands or, if you don't have competition, compare them to the losses of not buying your solution at all.

Find the Salient Benefits of Your Solution. The primal brain will not accept the burden of making complicated decisions. Too often, sales messages spew a list of reasons that customers should consider a solution. However, these reasons do little to motivate the primal brain to commit the energy required to consider them all. Therefore, you need to distill a limited number of benefits, and then demonstrate that no other brand or company can deliver a solution that is as unique and as effective as yours. Later in this book, we will elaborate further on how you can find your claims. Claims represent the compact list of the top benefits you offer. They can accelerate the decision and create contrastable situations that make immediate sense for the primal brain. Typically, claims will provide direct solutions to pains and grab attention to make your message completely relevant to an urgent threat or risk that your audience faces. Once you magnify a pain and show how your solution can solve it, customers will beg to buy your solution. As David Ogilvy famously suggested, selling is easy: “Just light a fire under people's chairs, and then present the extinguisher!”

Compare Your Solution to a Competitor. Contrasting your product or solution with that of a competitor is a good strategy. “Before and after” stories can do that as well. Show the life of one of your customers before they own your product or solution – it should be painful to see! – and then show the relief of their pain as the contrast. This scenario is the typical story that you see in an infomercial and for a good reason: it works!

The Neuroscience of Contrastable

For contrastable, we tested the following research question:

By comparing two products, two services or two situations, can we raise the persuasive impact on the primal brain?

We used the following advertising stimuli to test our hypothesis:

- Video advertisement for a dental discount card

- One ad featured customers of a dental‐care plan but did not show any form of contrast between “before” becoming a member and “after.”

- One ad featured a short story of two people who had to face the urgent need for dental care. One had a discount plan, the other did not.

- Weight‐Loss‐Supplement Print Ads

- Two ads featured a man who lost 39 pounds using a leading weight loss supplement.

- The first ad showed a man who had already lost the weight and showed the product.

- The second ad showed a man who had lost the weight but also showed a picture of him before he lost weight.

- Two ads featured a man who lost 39 pounds using a leading weight loss supplement.

The results supported our hypothesis:

- For the dental discount card ads, the ad featuring the contrast between before and after scored much higher on the primal brain than the other ad (+119% on the NeuroMap score)

- For the weight loss supplement ads, using a contrastable picture drew 38% more attention than the other one. It also produced less distraction and less cognitive effort.

Contrastable Neuroinsights: By making your ads more contrastable, you can raise the impact on the primal brain. Using contrast will also reduce cognitive effort by easing the choice customers need to make.

What to Remember About Contrastable

- Despite what we say, we do not like multiple buying options because it overwhelms our primal inclination to decide quickly and to do so with the least amount of brain energy.

- Comparing two situations makes decisions easy for the primal brain.

- Rather than stating: “Choose us because we are one of the leading companies in the XYZ industry,” highlight only a few unique benefits (claims).

- Contrast stories of before and after, or your brand against the competition, to help your customers decide.

TANGIBLE

“It is hard to explain just how a single sight of a tangible object with measurable dimensions could so shake and change a man.”

– H. P. Lovecraft, American author

Making something tangible means to achieve simplicity and minimize the cognitive energy necessary to process your message. The primal brain does not have the cognitive resources offered by the rational brain, yet it dominates the initial review process of any persuasive message.

Our Brain Is Green

The brain conserves energy all the time. You are looking at an organ that's only about three pounds – 2% of your body mass. However, it requires 20% of our entire energy to run properly, more than any other organ in the human body. Two thirds of that energy is used to fuel electrical impulses, and the remaining third is to perform cell‐health maintenance. At rest, our bodies consume about 1,300 calories per day of which the brain burns about 260 calories. Interestingly, the stomach is second in energy consumption. Indeed, we use 10% of our energy to digest, absorb, metabolize, and eliminate food. Why do you think there is such dynamic tension between the brain and the stomach right after lunch? That is why it is not recommended that you try to close a deal while people are still chewing on their food! There is a fierce competition between the brain and the stomach for precious energy.

So, the quality of making things tangible is the quality of serving information to the brain that does not require much mental effort. We welcome speed and simplicity because we welcome the opportunity to not waste cognitive energy. Let's simply reflect on one idiom that says it all: paying attention. What does this expression imply? That you are asking people to “spend something,” which is effectively brain energy. The reason we are so bad about consciously controlling our attention is that the primal brain is the guardian of that spending. Before you can even think of selling anything, you must sell the value of using your audience's energy to process your message.

When was the last time you were attending a workshop and found yourself thinking, “I wish this were harder on my brain?” It does not happen. The teachers we loved are those that made it easy and fun for us to comprehend their message. The same is true for your persuasive messages. Your audience is not prepared to read or hear all your explanations. You must take the burden of making your message crisp and simple so that they will know within seconds there is not a better option or a better decision than the one suggested by your message.

EEG data measures how much messages create cognitive effort. We do that by recording and analyzing brain waves, especially in the frontal lobes, where we control our concentration and use our working memory. Irrespective of how smart research subjects are, we always find that they do not enjoy exerting cognitive effort when processing advertising messages. Nobody will ever complain that your message is too easy to understand. On the contrary, people will stop paying attention if your message is too abstract, or too intangible. If you sell a physical product, arguably it might be easier to get people's attention from the primal brain, because that product has a physical form. It is real, concrete. However, if you sell software or a financial service, clearly you have a much bigger challenge to make it tangible.

Since our primal brain is biased to make quick decisions, we avoid complexity all the time. For instance, a 2012 study from Google and the University of Basel demonstrated that web visitors judge the aesthetic beauty and the perceived functionality of a website in about 50 milliseconds [88]. That is less time than it takes to snap your fingers or trigger a smile. First impressions are formed in the primal brain. Speed is inversely related to complexity. The research on the neurobiological basis of first impressions is rather scant. Aesthetic perception is an arduous process to understand and testing messages that have different aesthetic styles is tricky. Most of the media research on the subject comes from web analytics collected from websites that have varying degrees of complexity. However, a study confirmed that web pages of moderate complexity receive more favorable consumer responses [89]. Another one further established that web pages that are perceived as visually complex produced negative arousal and increased facial tension [90].

The Power of Cognitive Fluency

The value of making your message more tangible is supported by the study of how much we enjoy cognitive fluency. Cognitive fluency is the subjective experience of ease or difficulty to complete a mental task. It is a well‐researched bias that explains how much we favor processing information that is easy to understand. For example, we prefer people whose names are easier to pronounce than others [91]. Also, we remember better what is easier to learn [92]. Shares in companies that have easy‐to‐pronounce names tend to outperform others. The fluency of many cognitive processes is “pre‐assessed” by the primal brain. Anything that appears complicated within the first few milliseconds is likely to be rejected by the rest of the brain. For instance, whenever I talk about our persuasion model, I hold a brain in my hand to establish that I am passionate about the topic. Doing so increases people's attention and reinforces the perception that I am competent to talk about neuroscience! More importantly, it makes the SalesBrain model easier to understand because I am not just relying on words to explain it. It makes a complex topic more cognitively fluent.

In fact, using less energy to comprehend anything may be the ultimate expression of the brain's intelligence according to a fascinating study examining how much energy chess players consume [93]. Using an EEG to study the patterns of neuronal activity while playing a game, expert chess players were compared with beginners, and the results were very surprising. Master players had lower brain activation, and therefore displayed more neural efficiency than beginners. Experts use less brain energy than a novice. They also perform many tasks subconsciously [94]. Some scholars suggest that this study may unveil the neurobiological basis of intelligence. By that, they mean that intelligence may well be the ability of the brain to minimize the amount of brain energy used for a particular task.

Applying Tangible to Persuasive Messages

There are three effective ways to make your messages instantly more tangible:

- Use analogies and metaphors as shortcuts that help people grasp the essence of what you communicate.

- Use familiar terms, patterns, and situations when you explain. We learn best by pointing to what we already know.

- Remove abstraction by providing concrete evidence to prove what you say.

The Neuroscience of Tangible

For tangible, we tested the following research question: Can concrete evidence create more persuasive impact on the primal brain and reduce cognitive effort on the rational brain?

We used the following advertising stimuli to test our hypothesis:

- Dental discount‐card video ads

- One ad featured customers of a dental care plan without showing real customers as tangible evidence that the service was as good as the ad suggested.

- One ad featured several video testimonials of the dental care plan customers.

- Duct tape billboards

- One ad featured the product and one unproven claim: “It holds.”

- Another ad featured the tape as if it was holding a billboard together.

The results supported our hypothesis:

- The ad for the dental discount card featuring the testimonials produced a primal brain score 10 times higher than the basic ad, which did not include tangible evidence from customers.

- The billboard demonstrating the value of the duct tape received a primal brain score that was twice the score of the billboard demonstrating nothing concrete about how strongly the tape could hold.

Tangible Neuroinsights: By making your ads more tangible, you will create more impact on the primal brain and reduce cognitive effort on the rational brain.

What to Remember About Tangible

- The primal brain is the guardian of our cognitive energy.

- Don't expect messages that create cognitive effort to persuade.

- Making a message complicated is easy but achieving cognitive fluency is difficult.

- You need to work hard to create a simple, yet persuasive message.

MEMORABLE

“I'm trying to make sure that there's comedy as well as sadness. It makes the sadness more memorable.”

– Rick Moody, American novelist

Memory, or how information is encoded, is a complicated function of the brain. First, it is largely distributed across many brain areas, some located in the primal brain (hippocampus, amygdala), but also in newer cortical areas like the temporal lobes or the prefrontal lobes. A full discussion on memory is beyond the scope of this book but discussing short‐term memory and how you can improve your ability to impress upon your audience to make your messages more memorable is extremely important.

The U‐shape Curve of Memorable

First, the effect of a message on our short‐term memory is very much like a U‐shape curve. For example, do you remember your first car? We all typically do. Do you remember your last car? Not that difficult either. However, do you remember your fourth car? Not that easy! Discovered more than 60 years ago and proven by countless studies, the U‐shape curve effect is also known as the recency and primacy effect. We tend to remember the first occurrence (primacy) of an event and the last occurrence of an event (recency), but we forget what happened in between (see Figure 4.5).

Figure 4.5 Beginning and end effect.

Psychologists have shown that the primacy effect plays not only a role in the recall but also in decision making. For instance, the result of the reward we receive for a first experience greatly influences our subsequent behavior, a phenomenon called outcome primacy [95]. Thus, beginning and end points are important aspects of what happens with a message over time. It is because we have a unique – yet fragile – ability to remember. Therefore, the introduction of your message and its conclusion represent special opportunities to amplify the effectiveness of your story. You cannot afford to talk as much about your business, your mission statement, your products, and your services at the onset of your presentation or advertisement, because this part of your story is of no interest to the primal brain (Figure 4.6). Additionally, explaining your value from your perspective will inflict undue effort on your audience's brains. By communicating too much about your technology, your people, your products, you are on a mission to fail.

Figure 4.6 Spraying reasons to buy.

The Neuroscience of Message Recall

Message recall is the ability to retrieve and report information that has been presented to you for a few milliseconds, seconds, or minutes. There are three subsystems involved in this process:

- Sensory memory, defined as the retention of information by your sensory structures

- Short‐term memory

- Working memory

Sensory Memory. Our senses can store information for a very short period. For the auditory sense, it is called echoic memory. For vision, it is referred to as iconic memory.

Physiological recordings allow researchers to measure the trace of sounds in our brain. Echoic memory is critically influenced by the saliency of sounds we hear. For instance, a scream will tend to be remembered more than a whisper. Also, emotion is likely to influence how much we remember what we just heard. Indeed, we may retain entire sentences when our attention is heightened by a strong emotional response. This can help us retrieve several seconds of auditory information. On the other hand, our immediate recollection of visual stimuli is very poor. Estimates coming from visual studies suggest that we typically recall between 300 and 500 milliseconds of visual information we have just received. So, although both echoic and iconic memories are only able to hold information for a very short period, these forms of memory can store much more information we may not be able to recall consciously. Therefore, building a strong emotional beginning, especially re‐enacting a pain is critical. And finishing with a strong emotional “close” in your message is very important. Both techniques will be further developed in Chapter 8, Deliver to the Primal Brain.

Short‐Term Memory. Compared to sensory memory, short‐term memory can retain seconds and minutes from any interaction. It has long been proposed that short‐term memory is directly dependent on the stimulation of sensory memory first [96]. In other words, short‐term memory does not work well unless our senses have engaged in the recording of tiny fractions of our experiences. Meanwhile, long‐term memory is also highly dependent on short‐term memory, confirming that memorization is a complex process, distributed in multiple areas of the brain, but organized at its core by the primal brain.

In the 1950s, many psychologists were investigating how much we could effectively store in our short‐term memory. Studies from George Miller [97] initially suggested that no matter what information people were asked to remember (digits, words), the number of items that they could easily remember was around seven. However, there was a critical flaw in this conclusion. Although some information can be classified as “bits” – elementary pieces of information – other types of information represent groups of bits, commonly labeled “chunks or packets.” Using chunks makes us more efficient than remembering bits. For instance, we can easily remember a word of 13 letters, like “neuromarketing.” However, whereas some of the chunks (like words) may pass on to long‐term memory, a large majority won't. In fact, recent research suggests that long‐term memory may not be as dependent on short‐term memory as once thought. Instead, long‐term memory may be critically influenced by sensory memory. This further suggests that using seven reasons (or more) to influence your customers is not optimized for their short‐term memory. On the contrary, it confirms that your first goal should be to strongly activate their sensory memories. To achieve that, you cannot exceed three chunks of information (typically three words) to describe your value proposition – that is, your claims – and you need to make them visual, the dominant sense in the brain!

Working Memory. The concept of working memory is critical to how you can make your message more memorable. Working memory holds information in our brains for a short period (short‐term memory), and transforms the information to guide a decision, a thought, or a movement. Working memory can be stimulated by input coming from your senses (the ringing of your alarm clock), or from your long‐term memory (retrieving the address of the restaurant where you are meeting a friend). As you realize by now, the whole point of presenting a persuasive message is to make sure it is easy for people's brains to manipulate the information they receive. Therefore, your ability to persuade is completely dependent on the activation of your audience's working memory. Studies prove that the frontal lobes are extensively involved in activating the process by which we hold and manipulate short‐term information we receive. And SalesBrain's research shows that only messages that engage the primal brain first are successfully processed by our working memory.

Applying Memorable to Persuasive Messages

- To make your message memorable, create a narrative that will have limited and short attention dips.

- Narratives that work on the brain grab attention at the beginning and the end of each segment.

The Neuroscience of Memorable

For memorable, we tested the following research question: Can concrete evidence create more persuasive impact on the primal brain and reduce cognitive effort on the rational brain?

We used the advertising stimuli shown in Figure 4.7 to test the hypothesis that the beginning and end of an event matter more than the middle. We presented a list of 10 words to our subjects and we measured their recall after 20 seconds. We use words that are known to be influential words. The data does confirm the U-shape curve of recall.

Figure 4.7 Beginning and end recall.

Memorable Neuroinsights: Recognize that memorization is a complicated process for the brain. Make sure what you say is easy to retain and put a special emphasis at the beginning and the end of your message.

What to Remember About Memorable

- We are wired to remember basic information to guide our short‐term actions.

- Message recall is affected by sensory memory, which further influences both short‐term and working memory. Both are critical systems that make encoding fragile.

- The primal brain needs a solid narrative structure with a strong beginning and strong end to create attention and retention.

- Messages imprint better in the brain if they focus on the pain first.

VISUAL

“Dialogue should simply be a sound among other sounds, just something that comes out of the mouths of people whose eyes tell the story in visual terms.”

– Alfred Hitchcock, Filmmaker

When we conduct a neuromarketing experiment, data we collect from the visual system gives us crucial information on the effectiveness of persuasive messages. Why? Because the visual sense is the dominant channel through which we perceive the world around us.

The Visual Sense Is Dominant

Nearly 30% of the neurons in the brain are visual neurons. Researchers have confirmed for decades that the visual sense dominates other sensory processing systems. This phenomenon is commonly referred to as the Colavita effect [98], named after a researcher who was able to prove the superiority and speed of visual processing over auditory processing when subjects were asked to consider bimodal stimuli. In a recent study, researchers examined the neurophysiological correlates of visual dominance using EEG and confirmed the Colavita effect in multisensory competition [99]. They found that irrespective of the intensity of a stimulus, its type, its position (before or after audio, for example), the demands on attention, and arousal, the subjects committed more energy to the visual sense than any other sense. What is interesting about this research is that auditory stimuli tend to accelerate visual responses, suggesting that the brain looks for other sensory inputs to enhance visual processing. Also, while the visual sense is the fastest to engage, it has a longer processing cycle than auditory information.

The visual system is activated when we see and imagine while being conscious or unconscious (includes dream activity). Most persuasive messages rely on the direct delivery of visual information, which is typically processed by our eyes first. Eyes are sensors that convert photon particles (light), into information that the brain can understand – that is, electrochemical signals. These signals travel along the optic nerve, through the optic chiasm, and enter the brain first in the brainstem. From there, visual data travels to reach neurons that are located at the back of the brain in the occipital lobe, also called the visual cortex. There are over 30 columns of neurons responsible for processing color, motion, texture, patterns, and so forth. They are organized in visual areas that attend to basic information first, and more complicated interpretation next. However, what's really important, and rarely discussed in textbooks or research papers, is that before all this visual information goes to the back of the brain, some of it is processed by the primal brain ahead of the visual cortex [100]. Indeed, the first point of connection of the optic tract is in the brainstem. The brainstem houses critical visual stations – namely, the lateral geniculate nucleus and the superior colliculus. The lateral geniculate nucleus (considered part of the thalamus) plays a critical role assessing the importance and urgency of a visual stimulus, while the superior colliculus gives us the capacity to see without consciously knowing we see. Meanwhile, right above the superior colliculus is a tiny brain structure considered part of the limbic system called the amygdala. The amygdala has the power to control our entire body and move us away from danger in about 13 milliseconds [101]. Joseph Ledoux, a prominent neuroscientist and researcher on emotions and responses to threats at NYU showed that it takes about 500 milliseconds for the neocortex to recognize the legitimacy of a threat. Therefore, the primal brain is nearly 40 times faster than the neocortex to respond to a visual stimulus [102].

After the information has been processed by the lateral geniculate nucleus and the superior colliculus, visual data typically follows a ventral stream and a dorsal stream, each serving different processing functions. The ventral stream is called the what pathway because it processes the urgency of recognizing objects or situations we encounter. Upon the stimulation of the ventral stream, we may receive enough information to act. This is what Ledoux calls the “low road.” Low‐road processing demonstrates the importance of relying on visual data to survive. When we see something that looks like a snake, we do not think about it; we move away from it by shortcutting any engagement with the rational brain. Meanwhile, a dorsal stream, engaging primarily the parietal lobe to prepare and guide our behavior, also interprets visual data. Therefore, if we see something that looks like a snake, we use the dorsal stream to decide if we should change our walking course. The dorsal stream is called the how network because, without a healthy parietal lobe, we cannot figure out what to do with an object, or how to respond to a situation. In fact, the dorsal stream is also responsible for re‐assessing the self‐relevance of a situation confirming the critical importance of making a visual stimulus personal. However, let's be clear: visual dominance is not just a function of how much we fear death. It is truly our default decision‐making system.

Even Voting Is a Visual Decision

Some surprising research has demonstrated that we tend to cast our political vote for people who have the most visual impact on us. In a study conducted by Princeton University in 2006 [103], subjects were asked to “use their guts” to confirm which of two gubernatorial or senatorial candidates they would pick. With no prior knowledge of who these candidates were, they could only rely on the candidate's facial appearances. Yet, researchers were able to predict their picks over 70% of the time. The conclusion of the study is obvious: we are guided by the visual dominance of our primal brain, and we later rationalize choices made below our level of consciousness. Although none of the stereotypes attributed to how beauty or attractiveness is portrayed in media today, there is clear and undisputable evidence pointing to the importance of how we perceive the character of a person based on the way they look. For instance, we are better at judging personality traits of people we consider attractive after we meet them briefly than doing the same for people who are perceived as less attractive [104].

The Four Types of Visual Stimulation

There are four types of visual stimulation that are important to consider when you are on a mission to persuade an audience.

3D Moving Object. The most potent visual stimulus for the primal brain is a three‐dimensional object moving in space. The onset of motion captures the most attention of all [105]. Think about the impact of a lion starting to run toward you! Consider that, when you present in front of people, you are a live being moving in space, which is why you can trigger more attention than a video or an email ever will. Also, faces and their expressions capture more attention than any other object [106]. That is why using your body language is a critical visual stimulus. Face familiarity detection in the brain only takes 200 milliseconds according to a recent study using EEG [107]. Researchers have also shown that a lot of the visual processing of objects is “pre‐attentive.” This means that it happens mostly below our level of consciousness [108].

3D Static Object. The second‐best visual stimulus is a static three‐dimensional object. It could be an object you place on a table in front of you during a presentation, like a prop, a mock‐up, or a 3D model. Alternatively, the object can be you facing an audience while remaining still. In all these cases, even though the object is static, it may be of great interest for the primal brain, if the object is relevant to your audience and to the story of the value of your product, company, brand, or message.

2D Moving Image. The third most effective visual stimulus is a two‐dimensional image moving frame by frame. Of course, we are talking about a video. We enjoy them simply because visual frame changes are entertaining for our primal brain. This is true as long as the changes are not happening too fast. In the era of digital editing, video producers can display many frames in a very short period. However, studies we have conducted on the effect of videos on the brain show that our primal brain stops processing the meaning of a narrative when the speed of change is above three frame changes per second or below 35 milliseconds per frame. Above that speed, the information may still be processed below the threshold of consciousness, in which case the effect is called subliminal. Although the subject of the effect of subliminal stimuli has garnered much attention over several decades, the effects are minimal [109]. However, we now know that text and visual stimuli produce distinct subliminal effects – namely, because reading text requires complicated computational operations that involve not only the eyes but also the auditory cortex. Although subliminal perception is possible from either type of stimuli, visual primes receive more subconscious attention than words do. This, of course, is due to the dominance of the primal brain. Many scholars also explain this phenomenon by considering that language has evolved over a very short period compared to our biological ability to decode a visual stimulus, which predates the development of the cortex by millions of years [110]. Also, as we mentioned earlier, our ability to acquire visual information without conscious effort is enabled by old subcortical areas (like the lateral geniculate nucleus, the superior colliculus, and the amygdala), which process visual signals before they reach higher, more evolved cortical areas [111]. Finally, negative emotional videos produce more brain response than those featuring positive emotions, regarding both intensity and speed. To be persuasive, we recommend that a video should use a persuasive narrative with a pain‐centric drama. Also, you learned earlier that we need about 200 milliseconds to recognize a familiar face. So to recognize or connect with the characters of the story, remember that your audience needs at least 200 milliseconds of footage to do so [112].

2D Static Image. The fourth most effective visual stimulus is a picture – a two‐dimensional set of pixels. Notice I did not mention text or charts. Photos (objective form) are better at grabbing attention than illustrations (subjective form) because they require less time and energy to be recognized by the primal brain. Illustrations are not as effective because they are less concrete and potentially less familiar than real scenes captured by a camera. Using custom photography of situations that are unusual is effective if the objects, the context, and the nature in each photo are familiar to your audience.

The Power of Colors

Primates started to see in color –trichromatism – about 35 million years ago as the result of a mutation of the seventh and X chromosome [113]. As a result, they developed an evolutionary advantage to pick up fruits, detect predators, and become better at reading facial expressions. Colors have a specific effect based on their wavelength:

- For example, visible colors of longer wavelength (reds) have an innate effect of stimulant because they are associated with dangerous stimuli like fire, blood, lava, and sunsets [114].

Although the physiology of vision cannot explain all responses to colors, there are still many similarities among diverse cultures on how colors are perceived. For instance, in a study performed on 243 people from eight different countries researchers confirmed that blue, green, and white are always associated with calm, serenity, and kindness [115]. Another study performed in the United States showed that different colors and different shapes – circles, squares, angles, and waves – of lines communicated the following affective values [116]:

- Red is happy and exciting.

- Blue is serene, sad, and dignified.

- Curves are serene, graceful, and tender.

- Angles are robust and vigorous.

Once consumers have started to make a strong association between a product and a color, the evaluation of a new product that contrasts with the original color may fail [117]. For example:

- Pepsi introduced Crystal Pepsi a transparent drink whose color was too far from the regular brown and was quickly abandoned.

- Palmolive tried a new color for its dishwashing soap. The consumers considered it less “degreasing” than the yellow one and less “fresh” than the green.

Researchers have also demonstrated that colors play a role on memorization: red strongly increases memory for negative words, and green strongly increases memory for positive words [118]. Beyond a simple color association for a physical product, researchers have also established that certain colors impact the cognitive performances – for example, green stimulates creativity, whereas red inhibits intellect [119, 120].

In conclusion, the choice of packaging color, color of the product itself, color of the background where the product is presented, or color of the fonts in text will all affect the brain of your audience. As an effective persuader, make sure to use colors effectively.

Applying Visual to Persuasive Messages

Maximizing the visual appeal of your message is a priority. There are many ways to apply this core stimulus when you craft an ad, a corporate video, a commercial, a web page, and, of course, a face‐to‐face presentation.

First, always remind yourself that your audience will not process the entire visual stimuli. Only a fraction of what you show will be seen. Less is more. Eye‐tracking studies confirm that only a fraction of a web page or a packaging label will be processed by most people, regardless of age, gender, or education. There are 100 million receptors in the eye, but only a few million fibers in the optic nerve. Fifty percent of our visual brain is directed to process less than 5% of the visual world. It is as if our eye movements curiously help us see more of small areas, not more of big areas.

Second, focus on improving the saliency of your images. Visual saliency is the inherent quality your visual stimuli must have to capture and captivate your audience. We typically process details in the center of the visual field, but the contrast between an object and its surroundings makes it more salient. For example, when we designed the home page of the SalesBrain website (see Figure 4.8), we made sure that the key message elements would be salient. The pictures featuring the brain are complex, but the dark background helps the viewers focus their attention on the critical elements (water splash and funnel). The icons are simple, with clear white lines around three illustrations introducing our claims. The visual opacity map (Figure 4.9), which shows only the areas that are predicted to receive visual attention, confirm that the overall design is well balanced because the most important message elements have good saliency.

Figure 4.8 SalesBrain home page.

Figure 4.9 Opacity map of SalesBrain site.

On a web page, identifying a pop‐out object can take less than 100 milliseconds. However, that time will increase if you design objects that have more than three levels of differences from each other – namely, their sizes, their colors, and the speed of their motion.

Third, visual processing is done in stages. You must appeal to early processing stages where neurons are busy sorting the easiest elements to recognize first. Avoid using too many colors, for example, because this makes separating salient elements difficult to achieve. As the SalesBrain example demonstrates, using lines around objects helps the brain perform a pattern detection with less cognitive energy. The more visual your messages, the more persuasive they will be.

Sometimes, your messages might even save lives. Such as in the field of public health. There's been some interesting research showing the superiority of visual warnings over text (Figure 4.10). They are called picture warnings. More than 40 countries around the world are using such visuals, and they produce better results than text warnings, especially on young brains and brains of light smokers [121]. The younger the brains, the more important employing visuals and emotional content to influence behavior. This is important because lives are at stake, and you want to make sure that your message is communicating urgency.

Figure 4.10 Poster for World No Tobacco Day, May 31, 2009, Tobacco‐Free Initiative, World Health Organization.

To conclude, most people do not understand what making a stimulus visual really means, especially when you consider how visual data is processed in the primal brain. For instance, if you use bullets with text on your presentation slides, none of that data is visual! The primal brain sees letters as of if they were hieroglyphs, which mean they will trigger no meaning or urgency!

The Neuroscience of Visual

For visual, we tested the following research question: Can you make a message easier to process and more memorable by making it more visual?

We used the following advertising stimuli to test our hypothesis:

- Insurance print ad:

- One ad explaining the value of life insurance using text.

- One ad showing someone about to be eaten by a shark.

- Pictures and words of animals flashed for 10 seconds.

The results supported our hypothesis:

- The insurance ad using a visual grabber instead of text triggered more attention (27%), more arousal (+697%) and much more emotional valence (100x) while reducing cognitive distraction by 25%.

- The retention of animal pictures was over 90% of the list and 40% higher than the retention of the animal words (Figure 4.11).

Figure 4.11 Visual retention.

Visual Neuroinsights: By making your messages more visual, you will create more impact on the primal brain and make your message more memorable.

What to Remember About Visual

- The visual sense dominates all other senses.

- It takes only 13 milliseconds to process an image, but about 10 times more to process a word and nearly 500 milliseconds to process a decision that engages the rational brain.

- Making a message visual delivers the fastest and most important persuasive stimulus of all.

- Objects in movement attract the most attention.

- Saliency of objects is key.

EMOTIONAL

“We are not thinking machines that feel, we are feeling machines that think once in a while.”

– Antonio Damasio, neuroscientist

Emotions play a critical role in making your message persuasive because emotions are the basic fuel that trigger decisions. The role of emotions in decision making is well‐researched, but the topic has often been highly controversial. What are emotions? Do they derail us from making good decisions? Can we control them so that they do not affect our choices? These are just a few of the questions that have been debated for hundreds of years.

Let me introduce the seventeenth‐century French scientist, philosopher, and mathematician largely responsible for this discord among today's scholars and researchers, René Descartes. Descartes, one of the greatest scientists, gave us modern mathematics with the Cartesian representation of data (Cartesian comes from the name Descartes). For instance, when you plot x and y on two axes, you use Descartes's model. Descartes believed that reason drives the best of our decisions and it is only through logic and deduction that humans can pursue a path to a greater truth. He promoted a philosophical model called “dualism” in which he argued the mind and the body be two separate entities. For Descartes, the mind thinks like a god and is imbued with the capacity to use logic and reason, while the body cannot think and responds like a machine to basic instructions. In a famous book titled Le Discours De La Méthode [122], he suggested a step‐by‐step process to make the best rational decisions and developed the notion that only humans have rational souls: “I think, therefore I am.” So, Descartes inspired a long‐held view that humans are always driven by rationality. Hence, scholars have supported for decades the notion that emotions have little influence on the way we decide. In fact, many argue that we systematically use reasoning to compute the utility of a decision. Introduced earlier, the pursuit of more utility assumes that we seek to maximize the value of our choices by increasing the number of options. Doing that increases our probability of finding what we want. Supporters of the utility theory further believe that bad choices are caused by limited choices, not by inherent flaws in our decision‐making process [123].

However, behavioral economists, neuromarketers, and decision neuroscientists have revolutionized our understanding of how choices are made in the human brain. Their findings disprove the rationale of the utility theory because neurotransmitters affect our behavior in ways that revolutionize our understanding of decisions. One such transmitter is dopamine, which plays a critical role in emotional states related to predictions and rewards. For instance, in one study, participants who received synthesized dopamine were better at optimizing their choices than others. Other studies have shown that choices under uncertainty are difficult to make for patients with prefrontal and amygdala damage, confirming that emotions play a crucial role in making complex decisions [124]. Neuroscientist and prominent expert on the neurobiology of emotions, Antonio Damasio, is a fervent opponent of Descartes' dualism as well as any decision‐making model theory based on the dominance of rationality. In the book Descartes' Error [125], Damasio showed the fallacy of Descartes' argument by revealing the neurobiological processes underlying our decision‐making processes. For Damasio, emotions are the basic fuel that our brains need to make decisions.

According to Damasio, there is no such thing as a rational decision, because older evolutionary systems influence and often dominate our choices by recruiting the guidance of our emotional system. He claims that “Nature appears to have built the apparatus of rationality not just on top of the apparatus of biological regulation, but also from it and with it.” For Damasio, emotions play the role of a biological bridge between subcortical layers and higher‐level cognitive functions such as thinking or goal setting. In fact, there are more neurons extending from the limbic system (subcortical) to the neocortex than the other way around. Clearly, emotions influence our wants below our level of awareness. This explains why we cannot easily report our emotional states. All we can report is our interpretation of how rapid changes of key neurotransmitters make us feel.

To summarize, we make emotional decisions first and rationalize them later. Richard Thaler, recipient of the 2017 Nobel Prize in Economics, a prominent behavioral economist, behavioral economics, also claims that humans systematically avoid rationality and recruit emotions to make decisions. He coined this phenomenon misbehaving [126]. Our research also supports the notion that we decide emotionally and that the primal brain largely controls this process. Like Damasio, we argue that we cannot make decisions without the guidance of physiological clues provided by older regions of the brain. In fact, studies on patients with lesions in their orbitofrontal frontal cortex (OFC) show that they are not able to make good decisions because they fail to interpret the biochemical changes they experience after being emotionally aroused [127]. As a result, they perform poorly without the guidance of the emotional clues [18]. Meanwhile, neuroscientist and prolific author David Eagleman also argues that “emotions are also the secret behind how we navigate what to do next at every moment” [128]. Eagleman supports his statement by describing the case of patients such as “Tammy” who damaged her orbitofrontal frontal cortex, and as a result cannot receive emotional feedback from her body. She, too, was unable to make any decisions. To conclude, Eagleman insists, “physiological signals—are crucial to steering the decisions we have to make.”

Which Emotions Influence Most of Our Decisions?

Although the evidence coming from studies done with healthy or unhealthy subjects largely support the critical role of emotions in decision making, we need to recognize that we experience thousands of emotions in any single day. Most theoretical models on emotions are complicated and, to date, there are many different models of emotions attempting to measure, evaluate, and rationalize emotions. One of our favorite models of emotions was proposed by Robert Plutchik [129], a psychologist who developed a psychoevolutionary theory of basic emotions. The major tenets of Plutchik's model are as follows:

- Emotions affect animals as much as they affect humans.

- Emotions help us survive.

- Emotions have common patterns and can be categorized.

- There is a small number of basic or primal emotions.

- Many emotions tend to be derivative states from the primal states.

- Each emotion has its own continuum of intensity.

Plutchik created an organized view of emotions illustrated in Figure 4.12 as the wheel of basic emotions. Even though the model was introduced nearly 40 years ago, it is regarded as one of the most elegant ways to organize emotions from eight core critical states: anger, disgust, sadness, surprise, fear, trust, joy, and anticipation.

Figure 4.12 Plutchik wheel of emotions – first published in American Scientist.

The wheel of emotions helps you realize that creating a strong emotional cocktail is a function of activating a limited set of primal emotions that have opposite and negative effects (valence) on our responses. At the time Plutchnik developed his model, neuromarketing research did not exist, so researchers could not easily measure and predict the impact of a persuasive message on emotional valence.

Source: Adapted from Plutchik.

| Avoidance Emotions | Approach Emotions |

| Fear | Anticipation |

| Sadness | Joy |

| Disgust | Trust |

| Anger | Surprise |

Based on this model, the most effective emotional lift you can create should first include an avoidance emotion – such as reminding the prospect of their pain – followed by an approach emotion – such as letting them experience the gain. Producing a good emotional lift is challenging for most of our clients. For instance, many tend to resist starting a message with a negative emotion. Yet, it is the best path to a successful persuasive message, because the primal brain attends to negative events before positive events. Failure to act in front of a negative event has more dramatic consequences for our survival than ignoring a positive event. That is why the fear of regret is the most powerful negative emotion to amplify the effect of any persuasive message.

The Fear of Regret. Briefly discussed earlier in the book, the fear of regret arises when we expect outcomes to fall short of our predictions. We experience regret when we choose an option that turns out badly, or when we pass on an option that turned out to be better than the status quo. In both instances, there is a sense that we have lost something that we can no longer experience, and more importantly, that we have prolonged the risk of the threat of making the wrong decision. In their paper on the impact of regret on decision making, researchers from both France and the United Kingdom [130] demonstrated that there is an intricate neural network involved in decision‐making situations where regret is a key factor. They collected fMRI data while subjects participated in a gambling task. The data showed that the fear of regret generated higher brain activity in the medial prefrontal cortex, the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, the anterior hippocampus, and the amygdala. The anterior cingulate cortex is considered a general center of emotional processing with projections to the amygdala and the anterior insula, a brain structure that lights up when people experience disgust. In all studies focusing on the impact of regret, the same neural circuitry appears to mediate both the experience of regret and the anticipation of regret. Meanwhile, the stress produced by the fear of regret induces the release of noradrenaline from the adrenal medulla and the locus coeruleus in the brainstem. Noradrenaline is responsible for the fight or flight response managed by our autonomic nervous system [131]. Additionally, a slower system, the hypothalamus‐pituitary‐adrenal (HPA) axis releases both cortisol and adrenocorticotropic hormone to calm our body when we experience stress from regret. However, cortisol starts working only 30 minutes or so after the onset of a stressful event. Therefore, studies show that the immediate effect of a negative event is better recalled right after it occurred rather than later, presumably because cortisol lowers cognitive processing and retention. This only reinforces the importance of producing messages that include “regret stressors” right at the beginning to heighten your audience's attention and retention but finish with a positive emotion at the end. Indeed, the best way to lift your message after re‐enacting the fear of regret is to generate more anticipation in the brains of your audience.

The Power of Anticipation. Anticipation is a prediction that we will receive excitement, joy, pleasure, or happiness if we engage in a specific experience. Such prediction is rewarded by a powerful neurotransmitter called dopamine. Although a healthy dose of dopamine can create the fuel of our day‐to‐day motivation, it can also lock us into addictive habits [132]. Psychologist and popular author Adam Alter argues that addiction is a pattern of behaviors we reproduce because they stimulate our dopaminergic system. For instance, when we look at our cell phone over 300 times a day, drink too much alcohol, or consume mind‐altering substances, the chemical effect of dopamine is gradually less potent, hence it pushes us to continue a potentially destructive habit. Practically, persuasive messages can directly stimulate a healthy dose of anticipation. By magnifying the power of an excellent product or an innovative solution, you can stimulate a safe level of dopamine in your audience's brain.

To conclude, both the fear of regret and the power of anticipation can help you create the simplest, yet most powerful emotional lift.

Emotions and Memory

Triggering an emotional lift is crucial to hijack attention and to jump‐start the decision‐making process of the primal brain. However, there is another critical benefit from making your message more emotional – retention and recall are improved. Curiously, emotions not only affect both our decisions and behaviors, but also the encoding of all messages and events that mark our lives. According to neurobiologists, emotions have a direct effect on what and why we remember anything at all. Research performed by Jim McGaugh has confirmed that emotional arousal enhances the storage of our memories [133]. That is why we call emotions the glue of your message. Without them, what you say, present, or show will not stick. By the way, this explains why we recommend that you first activate a negative emotion. Stress hormones participate in this process. The ability to retain information is essential to our survival, and negative events tend to be remembered more than positive events [134]. It is as if we have a “record” button in our brain that is automatically activated during noteworthy events. It does make sense that we would be wired to remember events that produce a strong impression on us, and especially those that could cost us our lives.

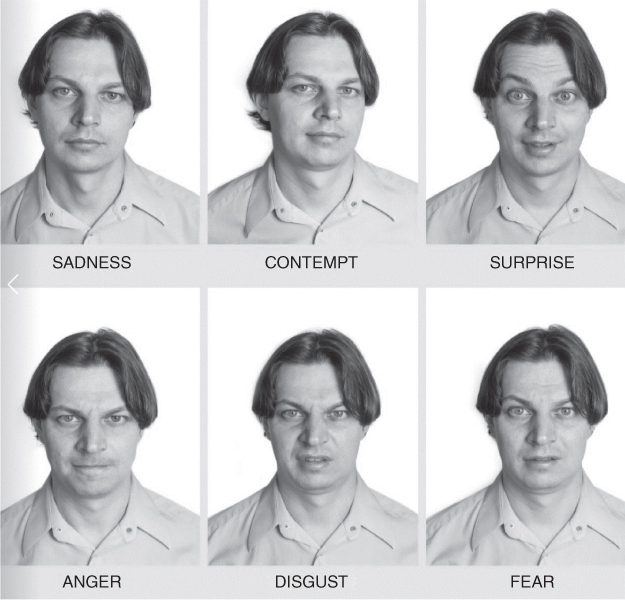

By creating emotional cocktails, you simply ensure that your messages are optimized to activate these automatic mechanisms. Meanwhile, emotions also produce physical movements on people's faces that are crucial to helping you monitor the effect of a presentation in front of a live person or audience. The visual cues you may receive from their micro‐expressions can confirm that you are successful at capturing their attention, that your message is triggering an emotional response. With the help of Dr. Wallace Friesen, Paul Ekman developed a comprehensive inventory of such movements over a 13‐year period (1965–1978). They called it the Facial Action Coding System (FACS). The FACS is a catalogue of 43 facial movements called action units (AUs). Each AU is anatomically unique and has its visual signature. According to Ekman, a limited set of emotions produce the same facial expression anywhere on this planet (see Figure 4.13).

Figure 4.13 Universal facial expressions.

Applying Emotional to Persuasive Messages

To ensure that you properly guide your audience to the behaviors you want, your message should first activate negative emotions that prompt us to avoid a situation. For instance, a negative surprise is one the most commonly used avoidance emotion to sell products or solutions that reduce risk or uncertainty, like insurance. If this negative emotion is relevant to your audience, then it will grab their attention and prime people to ask for a solution. In fact, at best, their mirror neurons will kick in to sample the stress that this situation may represent for them. Neuroscientists consider the existence of mirror neurons a crucial step toward understanding the basis of empathy and learning functions in humans [135]. It is now widely accepted that mirror neurons help us learn and sample people's emotions by simply observing their behavior. Later you will learn that one of the most effective ways to stimulate mirror neurons is to act out the pain of your prospects so they can personally relive it for just a few seconds. Once you have done that, simply activate an approach emotion by presenting your solution to their pain. This, of course, will liberate your audience from the tension you created by re‐enacting their fears. The emotional lift will produce more trust, more sense of safety, more joy, more love, or more excitement for the value you can bring. Never forget that a good emotional lift directly impacts the chemical balance of the brain. Stress or fear may indeed raise levels of noradrenaline, adrenocorticotropic hormone, and cortisol in the brain and throughout the body. Love and trust may produce elevated levels of oxytocin; laughter will raise levels of endorphins; happiness may raise serotonin levels; and anticipation will boost dopamine. Making your message emotional means using the power of brain chemicals to make your message more persuasive (see Figure 4.14).

The Neuroscience of Emotional

For emotional, we tested the following research question: Can you make the message more persuasive by increasing arousal using negative or positive valence?

We used the following advertising stimuli to test our hypothesis:

- Don't‐drink‐and‐drive print ad.

- One ad showed a text warning.

- One ad showed the face of a victim of a drink‐and‐drive accident.

- Video of protective products.

- One version of the ad featured the value of wearing a respirator.

- Another version showed a man at home using a barbecue recklessly and the same character at work wearing a respirator in complete control of the situation (safe versus unsafe).

The results supported our hypothesis:

- The ad featuring a victim of a drunk driver generated a huge spike of valence (+2600x) and a remarkable boost of cognitive engagement (+70%) compared to the text warning ad.

- The video featuring the emotional contrast between a character unable to use a barbecue safely but using a respirator at work also produced a huge spike of valence (+3800x) and reduced workload (–5%).