Chapter Five

Step V: Investment Decision & Portfolio Management

Time to pull the trigger?

You have identified a compelling investment idea, vetted it, and now must make a decision—buy, short, track, or pass. But, first let's take a step back and review how we got to this point.

In Step I: Idea Generation, we provided a framework for systematically sourcing potential investments. You learned how to screen for ideas based on valuation, financial metrics, and various corporate events, including M&A, spin-offs, and capital return. You also identified key macro and secular themes, and the most likely beneficiaries.

In Step II: Identifying the Best Ideas, you trimmed the list of potential investments on the basis of our idea review framework and investment write-up template, provided at www.investinglikethepros.com. You learned how to perform preliminary research focused on developing an investment thesis, evaluating a business, gauging management quality, assessing risks, and analyzing a company's financials and market valuation. Based on this initial work, you decided whether or not to continue exploring the opportunity.

In Step III: Business & Financial Due Diligence, you performed deep-dive fundamental research. You developed a true understanding of the business model, especially its key value drivers and risks. On the financial front, you examined the core financial statements to determine how the company makes, grows, and spends its money. In short, you formed a view on how the company will perform going forward.

In Step IV: Valuation & Catalysts, you determined what the company is worth. You also judged whether it is cheap or expensive, both on a standalone basis and vs. peers. Comps and DCF formed the core of this work with supplemental support from M&A-based valuation approaches, as appropriate. You also identified potential catalysts for driving a revaluation of the stock. This work culminated in setting a price target.

Now, in Step V: Investment Decision & Portfolio Management, it's time for the final verdict. In the event a buy or short decision is made, the work doesn't stop there. Going forward, the position must be constantly monitored for new developments that may change your initial thesis and PT, for better or worse.

If the stock is not compelling as a buy or short today, it can be placed in the track category. These stocks provide the seeds for future investments. They can be revisited later if a company's valuation or fundamentals change…or if a particular catalyst materializes. If you decide to pass, ideally that decision was made somewhere in the earlier steps.

Individual positions must also be managed within the context of the broader portfolio. Towards this end, we discuss fundamental portfolio construction and risk management techniques. Portfolio construction involves compiling a group of stocks that is tailored to your specific investment goals, strategy, and risk tolerance.

Correspondingly, risk management requires setting the proper risk/reward balance for your portfolio. Pay particular attention to position sizing, investment themes, sector concentration, geographic focus, and leverage levels. You also need to manage exposure to macro factors such as currencies, commodities, and interest rates. Key risk management tools include capping exposures, limiting losses, and profit taking, as well as hedging and stress testing.

Making the Investment Decision

Your due diligence and valuation work are complete. Now, you have a decision to make. This requires trust in your newly acquired skills and the courage to act. The proven ability to consistently make sound decisions over a long period of time defines a great investor.

Buy

You have followed our steps thus far and developed conviction in a given stock. This requires confidence in the business, financials, and valuation. It also means you believe the point of entry at today's share price is compelling. All of this fed into our assessment of Delphi at its IPO—namely, a clear BUY that offered secular growth at a cyclical price.

You do not want to fall into the trap of good company, bad stock. A great company can be a poor stock pick due to overpaying or mistiming. Microsoft is recognized as one of the most successful companies of all time, boasting a market cap of over $1.2 trillion at year-end 2019. Was it always a great stock pick though? As discussed in Chapter 1, after peaking at a $40 share price in late 1999, it took nearly 15 years for MSFT to break that ceiling.

As noted in Step IV, setting a PT prior to making the investment is a common best practice. It helps establish discipline and remove emotion from the decision-making process. Successful investors understand the parameters of their positions upfront and are prepared to exit as circumstances dictate.

Short

You have come to the conclusion that a stock is not a buy. But could it be a short? This decision requires the same level of diligence and conviction as a buy. Ironically, your search for compelling long opportunities may lead you to uncover ideas on the opposite end of the spectrum.

The decision to short a stock centers on the belief that it will decrease in value. The mechanics involve borrowing the shares (facilitated by a broker-dealer) and then selling them in the open market. Like anything borrowed, you ultimately have to pay it back. The short bet relies on being able to buy the shares back at a lower price in the future. Therefore, you profit from the spread between selling the shares at a given price today and buying them back at a lower price later.

During diligence, you may discover that the company or one of its peers is losing market share. Or, you may uncover a secular challenge to the business model, such as a change in pricing power or a low-cost emerging technology. You may even find a fundamentally inferior peer with unjustifiably high earnings estimates that is trading at a premium. Like Louis Pasteur, you may stumble upon an incredible discovery while looking for something else.

In general, short candidates are sourced from several common categories. These include external factors such as product substitution or obsolescence, structural pressures, shifting consumer preferences, cyclical peaks, and regulatory changes. They also include self-inflicted wounds, most notably accounting irregularities, mismanagement, overleveraged balance sheets, and misguided M&A. Common red flags include abrupt management turnover, unusually large insider selling, or a rapid succession of acquisitions.

Classic product obsolescence examples include the shift from print to digital media, e-commerce supplanting brick and mortar, and mobile devices displacing traditional cameras. Diligent short sellers were also rewarded by uncovering accounting malfeasance at Enron, SunEdison, Tyco, and WorldCom, among others.

Many investors use shorts on a tactical basis. This may be as part of a hedging strategy or selectively in the event a glaring short opportunity is discovered. There are very few pros, however, who have consistently made money with shorting as a primary strategy. Why? The market has a clear upward slope over time—since 1929, the S&P 500 has generated 11% annualized returns, including dividends reinvested. The short odds are also stacked against you due to ingrained institutional bias towards longs on the Street. Simply put, more actors stand to benefit when stocks are going up vs. down. You need to be highly skilled and selective to succeed given these circumstances.

Furthermore, your potential losses from a misguided short are unlimited. For a long position, if you buy a stock at $25 per share and the company goes bankrupt, your total potential loss is capped at $25. If you short a stock, however, there is theoretically no ceiling for share price upside. Your potential losses are uncapped.

Track

Some stocks may meet your business and financial criteria, but fail your valuation test. They are quality companies, but not currently cheap. Other stocks may be cheap but not quite attractive at the current time from a business or financial perspective. However, you see potential for them to improve and become long-term winners.

These ideas should be placed in the track category. As shown in Exhibit 5.1, our tracking sheet template lists relevant valuation multiples and other financial metrics for these stocks. Perhaps most importantly, there is a column for Price Target. This PT reflects your typical valuation work performed on the stock, as discussed in Step IV. When a stock on your tracking sheet trades at a meaningful discount to your PT (e.g., 25%+ within 12 months), you should be ready to revisit.

Ideally, you have been monitoring the company and keeping up-to-date on business and sector trends. In the event of a material share price decline, you need conviction that the drop is unwarranted and the original thesis remains intact. Alternatively, company prospects may improve such that you increase your PT. This may provide sufficient upside for you to reconsider the stock.

With every idea reviewed, you are building a database of potential core positions. In some cases, you may wind up tracking a stock for several years before it becomes compelling to own. Coming out of the depths of the Great Recession, some investors were able to buy high quality businesses they had been coveting for years at bargain basement prices. A time-tested value investing strategy centers on stockpiling quality ideas and then buying them opportunistically.

EXHIBIT 5.1 Tracking Sheet—Potential Ideas

Pass

The pass category is straightforward. This is a stock that you don't want anything to do with. It isn't compelling as a long, short, or future investment. Some passes you celebrate over time, others you regret. Regarding the latter, hopefully you can gain comfort with your rationale at the time, i.e., you followed the steps in our book and were methodical in your analysis. In the end, you simply made the decision that the stock wasn't for you. Discipline is a virtue—you don't want to force ideas into your portfolio.

Ideally, you made the decision to pass on a stock early in your investment process. Time spent on an eventual pass has a high opportunity cost. In the event the idea survived to this point, newly acquired knowledge can be applied to future investment opportunities. As you continue to research new sectors and companies, you continue to learn.

Monitor the Investment

The work doesn't stop once you initiate a position. You must follow your stocks closely and be prepared to adapt your thinking. New developments may change the initial thesis, sometimes at a moment's notice.

Monitoring your position involves constant reflection, analysis, and synthesis of company-specific and macro events that may impact the underlying business. Your due diligence never stops. You should always be reviewing and re-testing your thesis. Stay attuned to the risks you identified upfront.

The daily monitoring exercise centers on following company- and sector-specific news and research reports, as well as relevant economic data. On a quarterly basis, you dissect earnings releases and SEC filings, as well as accompanying investor presentations (if provided). Many pros also maintain a dialogue with investor relations (IR) or management. This extends to attending sector conferences where portfolio companies and their peers present.

Conversations with customers and suppliers also provide insight into industry dynamics and trends. This type of diligence helps you keep a healthy pulse on key value drivers and the competitive landscape. The same level of monitoring also applies to stocks on your tracking sheet so you can strike at the opportune moment.

We realize that if you're not a full-time investment professional some of the above work may prove challenging given time and resource constraints. But, if you're going to take stock investing seriously, you must be committed. We can provide the know-how but you must provide the can-do. We recommend that you carve out a block of time each day for portfolio work. At a minimum, you should read financial news on a daily basis and set up alerts for your focus stocks (e.g., Google Alerts).

Quarterly Earnings

Reviewing and processing quarterly earnings releases is a critical part of monitoring. Each quarter, U.S. public companies provide a full financial update and commentary on their prior three-month and year-to-date (YTD) periods, along with an accompanying 10-Q or 10-K and public conference calls.1 Management also uses this forum to update investors on guidance/outlook, key strategic initiatives, and sector trends.

Your earnings work centers on comparing the company's quarterly and YTD results vs. prior year reporting periods, as well as vs. sell-side consensus and your own estimates. Quarterly sequential trends can also be informative for certain companies, particularly those that are less seasonal. Just as important, you should keep track of prior quarterly beats and misses, which may reveal meaningful trends.

Listen to the earnings calls and then review the transcripts as well as the sell-side research reports that follow. Pay attention to the substance and tone of management's comments, particularly on key performance drivers. Each stock has its own hot buttons with investors. For some, it may be top line growth, for others it's margins. Regardless, outlook and guidance trump all. Don't be surprised if a company beats on sales or EPS but trades down because management's guidance was uninspiring.

You should also spend some time reading through the 10-Q (or 10-K), especially the MD&A for color on the quarter. The footnotes to the financial statements are also informative. Pros typically seek a follow-up call with IR or management to clarify key areas of outperformance or underperformance. This call is also used to test financial model assumptions.

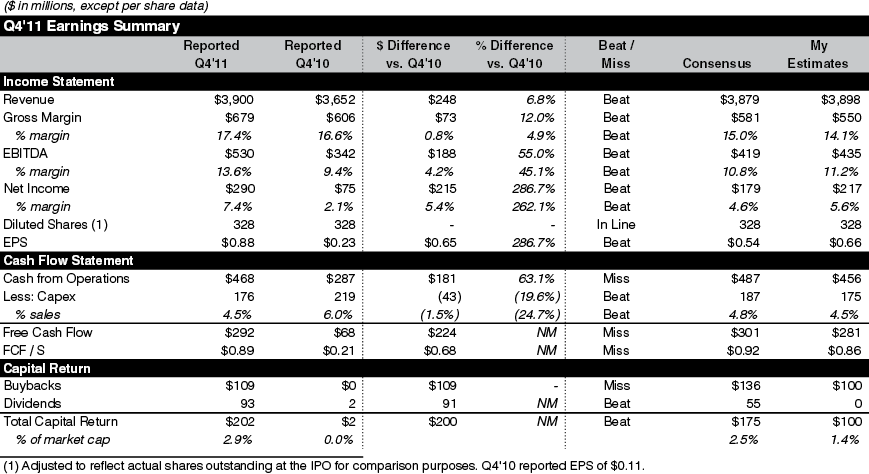

In Exhibits 5.2 and 5.3, we provide quarterly and annual earnings comparison templates for income statement and cash flow statement items. Your comparison sheet(s) may also include company- and sector-specific operating metrics, as well as segmented financials, if disclosed.

Our earnings templates below use Delphi's financial information for the fourth quarter ending 12/31/11, the company's first post-IPO earnings release. The annual template references Delphi's financial information for the full year ending 12/31/11.

In Q4'11, Delphi generated sales of $3.9 billion (+6.8% y/y), EBITDA of $530 million (+55% y/y), and EPS of $0.88 (+287% y/y), easily beating consensus estimates. In the same release, Delphi reported FY'11 sales of $16 billion (+16% y/y), EBITDA of $2.1 billion (+30% y/y), and EPS of $3.49 (+82% y/y). These dynamic growth rates reflected the rebound in Delphi's volumes off near-trough levels, improvements from cost-cutting initiatives, and operating leverage. Roughly two years after emerging from bankruptcy, the New Delphi's performance clearly reflected the company's striking transformational changes.

Key balance sheet metrics are also tracked. As shown in Exhibit 5.4, Delphi's leverage increased from 0.2x at year-end 2010 to 1x by year-end 2011. This was largely due to new debt raised to repurchase the $4.3 billion equity stake held by General Motors. On a net basis, Delphi's leverage was still only 0.3x given its large cash position. The company's 17.2x coverage ratio (12.1x on a capex-adjusted basis) was very healthy. Working capital intensity, as measured by NWC as a percentage of sales, increased slightly from 2.5% to 3.3%, which is not atypical for a fast-growing company. All in all, Delphi's balance sheet was in great shape.

EXHIBIT 5.2 Quarterly Earnings Comparison Template

EXHIBIT 5.3 Annual Earnings Comparison Template

EXHIBIT 5.4 Balance Sheet Comparison Template

Portfolio Construction

So far, we have focused on finding winning stocks. Each individual position, however, needs to be considered within the context of the broader portfolio. A large position should reflect its relative ranking vs. your other stocks in terms of risk/reward profile. It should also reflect the timing for potential catalysts. In short, your highest conviction positions should comprise the largest portion of your portfolio. At the same time, be mindful of your overall investment strategy, goals, and risk tolerance.

Crafting a winning portfolio requires paying attention to exposure levels. Foremost among these is individual position sizing, which determines how much you can make (or lose) on a stock. You also need to be mindful of indirect exposures. These may include specific sectors, geographies, investment themes, currencies, commodities, interest rates, and leverage. Therefore, your initial portfolio construction work must ensure you're not taking directional bets on commodities or currencies, for example, without realizing it.

In some cases, you may be comfortable with concentrated exposure levels. Common examples include being overweight a specific stock, sector or geography. Similarly, if you believe cyclical stocks will outperform over the foreseeable future, you may be comfortable overweighting that investment theme.

Below, we discuss key portfolio construction considerations (see Exhibit 5.5).

EXHIBIT 5.5 Portfolio Construction Considerations

Portfolio Construction Considerations

- Investment Goals

- Risk Tolerance

- Position Sizing

- Sectors & Geographies

- Investment Themes

- Currencies

- Commodities

- Interest Rates

- Leverage Levels

Investment Goals

Setting clear investment goals at the onset is key for crafting a portfolio. First and foremost, let's focus on targeted returns. Is your goal to maximize absolute returns or beat a benchmark such as the S&P 500 or MSCI World?2 Are you focused on achieving double-digit annualized returns, absolute risk-adjusted returns, income generation, or capital preservation? Regardless of the specific goals, your portfolio construction needs to be aligned.

These goals should also reflect your time horizon. Are you long-term focused, say three-to-five years or more? If so, you may have the staying power to weather potential dips along the way. Or, are you beholden to more frequent monthly or quarterly demands? In this case, you may sidestep highly volatile or illiquid stocks. For individual investors, personal liquidity requirements, retirement timeline, and return goals help dictate the time horizon. This becomes more complicated if you manage outside money and are subject to periodic reporting and redemptions.

Risk Tolerance

Risk tolerance is directly linked to your investment goals. An income-oriented or capital preservation strategy is inherently less risky than one aimed at maximizing returns.

You also have to be honest with yourself. A concentrated long portfolio, for example, can be subject to dramatic swings in either direction. Your temperament and conviction level is critical to seeing this type of strategy through. It also requires patient capital that will stay the course during periods of volatility. As British economist John Maynard Keynes famously stated, “ the market can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent.”

Prudent portfolio construction also requires you to consider the volatility, or beta, of certain positions. A small-cap biotech stock, for example, invariably has a higher beta than a blue-chip consumer staples stock. So, if you're unable to stomach a potentially large drop (or drawdown) in a given position, you may want to minimize exposure to high-beta, volatile stocks. In the event one of your positions does experience a large drawdown, be sure to keep a cool head and not panic. Volatility may create opportunity.

Position Sizing

Approaches to position sizing can vary dramatically from investor to investor. Some view concentrated positions as essential to driving outsized returns. If you have a few high conviction ideas—so this line of thinking goes—it makes sense to back them. David Abrams of Abrams Capital and Seth Klarman of The Baupost Group come to mind as proponents of this philosophy. Others, however, believe in broader portfolio diversification.

Whether you're running a concentrated or diversified portfolio, your sizing approach should weigh the merits of each position relative to others. If you don't get the sizing right, you risk endangering your portfolio or missing valuable upside.

So, how do you size your stock picks? Should it be a 5%, 10%, or just a 1% “ research” position? What is your conviction level with the particular stock at this point? Are there imminent catalysts that could drive the share price meaningfully higher? How does the risk/reward proposition compare to your other ideas? The PT work performed in Step IV is essential for force-ranking your positions and sizing accordingly. This enables you to construct a portfolio where the best ideas have the greatest weighting.

From a tactical standpoint, you may want to consider leaving dry powder, or excess uninvested capital, to size up opportunistically during market or company-specific hiccups. Maxing out your position early may mean missing out on the ability to buy future dips, especially during moments of market panic. Building a position over time also allows you to “ scale into” your stock as you gain confidence in the thesis.

On the other hand, there may be situations where a max position is justified at the onset. This requires high conviction at an attractive entry price, or time sensitivity due to an imminent catalyst.

Sectors & Geographies

As with the sizing of individual positions, many investors have guidelines for max exposures to specific sectors and geographies. For example, you may limit your tech sector exposure to no more than 20% of capital. Or, you may cap your European exposure.

You also need to be mindful of the correlation between concentrated positions and the rest of your portfolio. If your largest position is an auto OEM, you may want to limit auto exposure in the rest of your portfolio. This way a sudden dip in the economy or auto cycle won't wipe out your returns. Don't get us wrong—if you have strong conviction in a particular sector or geography, being overweight is fine. Just be mindful of the risks and manage them accordingly.

There are constant reminders of the perils of over-concentration. Those heavily invested in energy heading into late 2014 and 2015 got hammered as oil prices fell precipitously. Other iconic examples include overexposure to internet stocks in the late 1990s, bank stocks in 2008, European stocks in 2011, specialty pharma in 2015, and retail in 2017.

Investment Themes

Investment themes refer to ideas centered on a specific corporate strategy or attribute. For example, your research may suggest that M&A platforms are likely to outperform given an attractive financing backdrop and market support. Other themes might be turnarounds, value stocks, growth stocks, earnings compounders, or cyclical plays at a perceived trough.

As with sector and geography, overconcentration in a given investment theme can be perilous. For an M&A strategy, a collapse in the debt markets could shut down those plays overnight. Similarly, for a strategy focused on cyclical troughs, your timing better be right.

Once certain themes become popular, they tend to attract a crowd. Fast money moves quickly, both in and out. Hence, despite the initial investment merits of these stocks, they are highly susceptible when circumstances change for the worse. It doesn't matter whether the problems are company-specific or market-based. Low conviction investors head for the exits. When things go wrong, you don't want to be the last one holding on.

Currencies

Currency exposure is a close cousin to geographic exposure. For portfolios with stocks that have significant international sales, currency fluctuations can meaningfully impact earnings and performance. For example, a steep drop in the Euro may dramatically affect a U.S.-domiciled stock with a large portion of its earnings in Europe. This is known as foreign currency translation risk.

A classic example occurred during the March 2014 to March 2015 period when the EUR/USD exchange rate dropped from 1.40 to 1.05, a 25% devaluation. As a result, a U.S.-domiciled company with 50% of its earnings from Europe would have seen a 12.5% decline in its reported USD financial results for that period based on currency alone.

At the individual company level, this risk must be identified and analyzed upfront. You need to understand how currency fluctuations can impact earnings and performance in various scenarios. This approach is then extended to the portfolio level where currency concentration can be hidden across multiple companies.

Commodities

“ Commodity” stocks have higher cyclicality and volatility by their very nature. While the promise of super-cycles or “ this time is different” thinking can prove seductive, you must give the commodity cycle due respect. A sudden shift in the price of oil, resin, copper, or steel—to name a few—can devastate an overexposed portfolio.

Dramatic commodity moves produce clear winners and losers. A sharp drop in oil prices hurts the producers' profits but helps the airline and trucking industries. Similarly, higher steel prices may help the mills but hurt manufacturers dependent on steel inputs for their products. This type of exposure can be mitigated through hedges in addition to capping position sizes.

Interest Rates

A portfolio's exposure to interest rate movements should also be managed. As witnessed in the post-Great Recession era, low interest rates can provide large tailwinds across the board. Consumers have incentives to spend vs. save on the margin. The same holds true for companies who have the ability to borrow at attractive rates to fund growth capex, acquisitions, and capital returns.

Conversely, tighter monetary policy characterized by rising interest rates can create headwinds, especially in the absence of a growing economy. High dividend-yielding stocks, as well as leveraged companies with substantial floating rate debt, are particularly vulnerable. Stories reliant on debt-funded growth, buybacks, or M&A are also affected. Portfolios overweight these stocks require heightened awareness and intelligence. You must be prepared to move decisively in the face of new information around potential rate movements.

Leverage Levels

Leverage is a double-edged sword. The proper balance can be a powerful tool for creating shareholder value. Cheap debt fuels organic growth, as well as accretive M&A and return of capital to shareholders.

During difficult times, however—whether macro-driven or company-specific—a heavy debt load can be damaging or even fatal. Many companies that entered the Great Recession with a highly-leveraged balance sheet went bankrupt. A combination of plummeting cash flows and the inability to refinance maturing debt proved insurmountable. Others survived but the shareholders' equity was seriously impaired and took years to recover, if ever.

Let's look at Charter Communications. By late 2008, after a multi-year debt-fueled acquisition binge, leverage reached nearly 10x. The associated high interest expense, coupled with sizable capex requirements, was crippling. Capex-adjusted coverage was under 1x, meaning CHTR didn't have enough cash to make interest payments. Furthermore, the company was unable to refinance maturing debt when the capital markets dried up during the Great Recession. In January 2009, Charter missed an interest payment and filed for bankruptcy.

After exiting bankruptcy in November 2009, Charter emerged with a significantly improved credit profile. Leverage was reduced to 5.5x and the company established a credible path to further deleverage. CHTR was a classic case of “good company, bad balance sheet.” It was also a victim of bad timing given the disastrous state of the capital markets in late 2008/early 2009. In a more constructive environment, the chances for refinancing would have been better.

You need to monitor leverage levels for both your individual stocks and overall portfolio. If the average leverage across your portfolio is 4x vs. the market at 2x, then a downturn would likely have a disproportionately negative impact on your performance.

Portfolio Summary

Portfolio construction goes hand in hand with portfolio risk management. You need to be diligent on the front end to protect yourself on the back end. In Exhibit 5.6, the upper tables show exposure by top 10 positions as well as their leverage. For example, Position #1, the largest, also has relatively high leverage at 2.8x. You can then extrapolate the same for positions #2 through #10.

On the upper right, the portfolio is segmented by market cap and liquidity. Over 40% of the portfolio is represented by stocks with market cap greater than $25 billion. Only 5% have market cap of less than $1 billion. In terms of liquidity, the entire portfolio can be sold down in 25 days or less. Of that group, 75% need only five days or fewer to exit.

By sector, the largest exposures are communications, discretionary, and technology. By geography, the U.S. represents 68% of the portfolio. The U.S. Dollar (USD), however, is slightly less at 65% given the U.S. companies' exposure to the EUR, GBP, and JPY, among others.

Taking stock of this illustrative portfolio in Exhibit 5.6, we made some key observations. First, it is relatively concentrated with the top 10 positions comprising 60% of holdings. As an offset, it is diversified by sector and also highly liquid. Second, while the overall portfolio is moderately leveraged, certain positions tilt towards the high end. There is also a fair amount of FX exposure. Having flagged these potential portfolio hot spots, you may make adjustments upfront or implement hedges for protection.

EXHIBIT 5.6 Portfolio Snapshot Template

Portfolio & Risk Management

As noted in Klarman's 2012 year-end letter: “We continuously worry about what can go wrong with each investment and the portfolio as a whole; avoiding and managing risk is a 24/7/365 obsession for us.” Below we provide you with key tools to put this into practice.

Risk management must be performed at both the stock and portfolio levels. Just as each position must be monitored, so too must your entire collection of stocks. This involves a holistic assessment of the portfolio and the ability to quantify downside risks. Disciplined investors establish risk guidelines to optimize their portfolios and protect against losses.

Given the wide variety of funds and strategies, approaches to risk management vary accordingly. Multiple factors need to be considered, including target returns, risk appetite, fund size, investor base, capital stability, liquidity, and expected holding period.

The first step in effective risk management is to identify major portfolio hot spots. You can't measure and mitigate what you don't see or understand. As noted in Exhibit 5.6, these exposures may relate to a specific sector, geography, or currency. You also need to be prepared to quantify downside risk for various scenarios.

Ideally, key risks are flagged during your initial portfolio construction phase and a risk management strategy is mapped out concurrently. This means establishing an early warning system with clear thresholds for action. For example, if the investment thesis is based on an M&A strategy, you need to take particular notice if the financing markets dry up. Similarly, in a portfolio with heavy energy exposure, you need to be able to move quickly and decisively if your views on oil prices change.

Therefore, while successful investing requires a framework and discipline, it also requires flexibility. In a dynamic and ever-evolving market, it is critical to be adaptable and reassess your portfolio as new information comes to light. A stubborn allegiance to old views or bright lines may jeopardize performance.

If risk identification is the necessary first step towards effective risk management, then utilizing techniques for mitigating these risks is the second (see Exhibit 5.7).

EXHIBIT 5.7 Portfolio & Risk Management Tools

Portfolio & Risk Management Tools

- Exposure Caps

- Loss Limits

- Profit Taking

- Rebalancing

- Hedging

- Stress Testing

- Performance Evaluation

Exposure Caps

Perhaps the simplest method for managing risk is to set limits on the dollar or percentage amount for positions. This exposure may relate to single stocks or be aggregated by sector, geography, or investment theme. Some investors have hard and fast rules for sizing, e.g., a 10% cap for single stocks within the portfolio or 20% for specific sectors. Others are more flexible, allowing room to oversize best ideas while being cognizant of the risks.

According to a 2012 study by professors at Wharton and Booth,3 nearly 45% of hedge funds had stated guidelines on the dollar value or percentage of assets that any one position can represent. The remaining 55% of funds had no restrictions. Clearly, many investors manage concentration risk through common sense and ongoing vigilance, as opposed to strict guidelines.

Loss Limits

In the event a stock pick is not working, there should be a mechanism in place to limit losses. This takes the form of share price downside thresholds that trigger revisiting your thesis to verify that nothing has changed—e.g., down 10% or 15%. Your downside PT work is particularly informative in this regard (see Step IV). It helps you avoid the trap of letting your original cost basis influence your go-forward decisions. The market doesn't care what you originally paid for a particular stock…

Stock investors have the luxury of participating in a liquid market where publicly-traded shares can be bought today and sold tomorrow. While this has obvious benefits, do not be lulled into a false sense of security. Drawdown guidelines in accordance with the aforementioned 10% or 15% dips can provide discipline for investors to reconfirm their thesis in a given stock. These guidelines may be tested by a major earnings miss, negative guidance revision, or other challenges.

If a position moves against you, your conviction level will be challenged. This is a difficult moment for any investor. A prized stock sells off on new data. You need to quickly assess whether this is serious or fleeting, and make a decision. The pressure is on. So-called experts are telling you that the stock is a loser. What do you do?

Regardless of the decision, you must avoid confirmation bias at all costs, i.e., cherry-picking information that favors your investment thesis. Loss limit guidelines help you avoid this bias and dispassionately exit if the thesis is “ broken.” These guidelines, combined with proper monitoring and risk assessment, were critical for evaluating Delphi post its late 2017 spin transaction. As with any major event, the investment thesis needed to be retested … and several factors had changed materially (as we discuss in the Post-Mortem). Fortunately, our system will have you prepared for these situations. If one of your positions isn't working, you must constantly ask yourself, “ what am I missing?”

Of course, your reassessment may suggest that the stock is even more attractive given the new discount to your view of value. In this case, it might make sense to buy more. Real-time analysis and reassessment needs to be blended with strict adherence to guidelines.

Profit Taking

As the late investor Bernard Baruch wisely noted: “Nobody ever lost money taking a profit.” Proper risk management often dictates taking profit opportunistically once your PT has been reached. This is particularly true when further upside appears limited.

Profit taking also applies if a stock skyrockets ahead of schedule. In a scenario where an investor purchases shares at $50 with a 3-year PT of $100, it may be wise to consider selling some stock if the share price reaches $75 within six months, for example. This also provides dry powder to add to the position if the price declines. Of course, a positive change to the thesis or upward earnings revisions may support holding on.

The PT serves as an important tool for guiding your approach to profit taking and helping protect us from ourselves. It is human nature for investors to fall in love with their best stocks, even more so when they are outperforming. Therefore, once the PT is reached, effective risk management forces you to actively reestablish conviction in further upside. This inevitably involves setting a new, higher PT based on updated information.

Rebalancing

Rebalancing your portfolio requires the same blend of common sense and guidelines that dictates overall risk management. You must always be ready to adjust your portfolio in line with new company and market data, as well as exposure caps, loss limits, and profit taking.

Let's examine an illustrative scenario where healthcare represents 20% of your overall portfolio. Over the next three years, your healthcare positions increase by 100% while the remaining portfolio is flat. As a result, your healthcare exposure is now 33%. Strict rebalancing would dictate that you revisit where to allocate the excess 13%. Of course, you may also decide that healthcare is the best place for that exposure and stay overweight.

In another scenario, you take profit in a large position and find yourself with dry powder. Your first move may be to allocate towards existing high conviction ideas. Alternatively, you could rebalance by investing in new stocks sourced from your tracking sheet or ongoing idea generation process.

Hedging

Hedging aims to mitigate risk by taking a position designed to offset potential losses from another investment. The actual hedge may take multiple forms, including offsetting stock positions, options, index futures, and various types of derivatives. Hedges can be used to offset idiosyncratic risks for individual stocks or the market as a whole.

We focus on offsetting stock positions and the use of options, such as calls and puts. It is important to note that it is not always necessary to hedge, and can be costly to do so. A truly diversified portfolio with a prudent risk management approach may be sufficient.

Pairing

A pair trade is a form of hedging where you go long one stock and short a similar one that you believe will underperform. The two stocks are typically within the same sector or serve the same end markets. For a given long, you seek an offsetting stock with inferior prospects. The goal is to realize profit as the long outperforms the short in rising and falling markets.

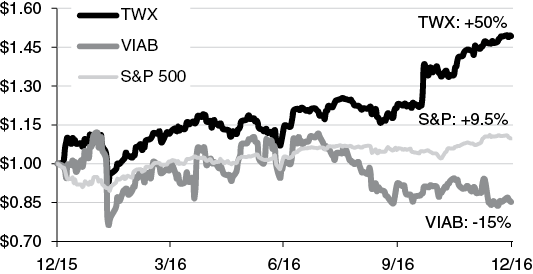

In 2016, a particularly successful pairing strategy in the media sector consisted of: 1) long Time Warner Inc. (TWX)4 and 2) short Viacom (VIAB). The thesis relied on TWX's ownership of must-have programming including HBO, CNN, and long-term sports rights, as well as Warner Brothers studio. The proliferation of online video was also creating more buyers for TWX's content. Meanwhile, VIAB was experiencing higher-than-average subscriber declines, lower ratings, and decreasing advertising revenues.

This pair trade proved successful with TWX outperforming and ultimately attracting a takeover offer from AT&T. As shown in Exhibit 5.8, $1 invested in TWX at year-end 2015 grew to $1.50 by the end of 2016. At the same time, $1 invested in VIAB decreased to $0.85, thereby generating significant alpha5 on both sides of the trade. An investor who was long $1 of TWX and short $1 of VIAB would have made $0.65 on the combined trade.

EXHIBIT 5.8 $1 Invested in TWX vs. VIAB in 2016

Options

Options provide the contractual ability to buy or sell a stock at a set price by a predetermined date. A call provides the right to buy a stock at a set price (strike price) until a set expiration date. A put provides the right to sell at a set price by a set date. A typical options-based hedge consists of buying a put as protection against a potential long position decline.

For example, you own a stock that is trading at $50 but believe there is short-term downside risk. Let's say you buy a put for $16 with a $50 strike price. In the event the share price drops to $40, you can sell your shares at $50 and make a $9 profit ($50 strike price minus $40 minus $1 premium). If the stock instead stays above $50 through the expiration date, you only lose the $1 premium.

Options can also be used to express a long position without taking much risk. For example, let's assume a stock is trading at $50 and you believe it could rise to $60 over the next three months given a pending catalyst. However, if the catalyst doesn't materialize, there is risk the stock could drop to $40.

Instead of buying the shares at $50 and risking 20% downside, let's assume you can buy a 3-month call option with a strike price of $50 for a $1 premium. In this scenario, if the shares fall to $40, you simply lose the $1. Meanwhile, if the shares rally to $60, you have the option to buy the stock at $50 and make a $9 profit ($60 minus $50 strike price minus $1 premium).

Stress Testing

Stress testing is used to analyze hypothetical performance under various scenarios or “stresses.” For example, you might test the effects of material USD, oil price, or interest rate movements on your holdings.

Ideally, during the portfolio construction phase, you identified key exposures for both individual stocks and the portfolio as a whole. For example, you should know what percentage of each company's profits are exposed to the energy sector. You can then sensitize how much a certain percentage move in oil prices could affect EPS and share price. We performed this exercise for Delphi's sales and EBITDA in Exhibit 3.7 with regards to auto production volumes, EUR, copper, and oil.

A simple approach for calculating share price impact would hold the P/E multiple flat (or more likely assume contraction) and multiply it by the pro forma EPS. This exercise is performed for all individual stocks and then aggregated at the portfolio level to determine downside scenarios.

Your stress testing should be guided by historical precedent. For the oil price example, you should test all the way down to (and potentially through) historical lows. You should also examine how a company's share price performed historically at given oil price thresholds. A portfolio stress test based on other factors (e.g., exchange rates or interest rates) should be governed by similar principles.

Performance Evaluation

You need to be able to measure your success. Pros typically benchmark their performance to an index, such as the S&P 500 or MSCI World. Others benchmark to a more specified or customized index in line with their investment strategy.

The ability to measure success requires a system that tracks performance at various intervals, e.g., daily, monthly, quarterly, annually. Investors with longer track records also benchmark performance accordingly, e.g., 3-year, 5-year, 10-year, and from inception (see Exhibit 5.9). Ultimately, your success will be judged by performance vs. your investment objectives and benchmarks.

As you review results vs. your benchmarks, seek to isolate key drivers of outperformance or underperformance. This helps you identify winning and losing strategies alike. You can then rebalance your portfolio as appropriate with regards to individual stocks, sectors, or investment themes. For example, you may find that your turnaround situation picks have been consistent winners and overweight accordingly going forward. Or, perhaps you haven't performed as well in healthcare as technology, and decide to pivot in this respect.

Long-term success requires serious discipline and adherence to the basics, coupled with adaptability. Complacency is the enemy. Just because something worked for a quarter, year, or even longer, doesn't mean it will work forever.

In the event of sustained underperformance, you need to pause and take a step back. What isn't working and why? Revisit your overall portfolio strategy and risk management procedures. In short, go back to Step I and systematically retest and reconstruct the portfolio. Your analysis may actually find that the existing portfolio is solid with meaningful pent-up performance. In this case, perhaps the best strategy is to largely stay the course.

This same introspective approach applies to individual stocks. Upon exiting a position, look at how the stock's performance played out vs. your original thesis. This involves an honest assessment of what went wrong and what went right. Following this disciplined approach will lend towards success in future investments. Past mistakes can be avoided and winning formulas replicated.

EXHIBIT 5.9 Illustrative Historical Performance – Fund vs. S&P 500

* S&P 500 returns assume dividends reinvested

Key Takeaways

- Investment decisions require conviction—make sure you've done your homework

- Don't fall into the trap of good company, bad stock—the right entry price and timing are crucial

- Once you initiate a position, the due diligence never stops

- Position sizing should reflect a stock's relative risk/reward profile—your highest conviction stocks should have the highest weighting

- Portfolio construction needs to reflect your investment goals and risk tolerance

- Identify key exposures upfront and establish a risk management strategy accordingly

- Key risk management tools include exposure caps, profit taking, and rebalancing

- You must have the discipline to cut your losses in the event your thesis is “broken”

- Portfolio evaluation helps identify elements of your process/strategy that are working or need help

Notes

- 1 The time and access codes for these quarterly calls are provided on a company's corporate website. These calls are also typically webcasted, available for replay, and transcribed by various financial information services.

- 2 As of 2019, the MSCI World Index consisted of stocks from 23 developed market countries, representing ∼85% of the market cap in each country.

- 3 Cassar, G., Gerakos, J., 2012. How do hedge funds manage portfolio risk?

- 4 Not to be confused with Time Warner Cable.

- 5 Excess return over a market benchmark, such as the S&P 500.

- 6 The price of a call or put option (“premium”) is typically determined in accordance with the Black-Scholes model. It depends on various inputs, most notably strike price, expiration date, and volatility of the underlying shares.