Chapter Four

Step IV: Valuation & Catalysts

What's the stock worth?

By now, you know how to analyze a company's business model and how it makes money. You also know how to measure financial performance. Now it's time to dig in on valuation. This sequencing is important. How can you value a company without first understanding the business and its underlying financials?

Our first book, Investment Banking, provides a 400-page, 100,000-word overview of valuation. This chapter captures the most critical concepts in a fraction of the space.

Your valuation work needs to address two key questions. First, what is the company worth? Second, how does that compare to its public market valuation? In other words, is the stock attractive at the current price? Your returns depend on paying the right price at the right time—avoid the trap of “good company, bad stock.”

Our valuation discussion starts with the basics. The essential Wall Street toolkit includes a mix of market, intrinsic, and M&A-based valuations. We also cover some of the more nuanced tools including sum-of-the-parts and net asset value.

Other approaches to valuation are less technical and more event-driven. So-called “catalysts” have the potential to drive meaningful share price appreciation. They may be internally-driven as part of an evolving management strategy or external, such as shareholder activism.

A combination of the above-mentioned valuation tools is used to determine your price target (PT) for a given stock. The PT is a core component of the final investment decision, whether buy, short, track, or pass. Without it, you cannot properly quantify the upside potential and risk/reward trade-off.

Valuation

In the pages that follow, we detail the key valuation tools used for stock picking (see Exhibit 4.1).

EXHIBIT 4.1 Valuation

Valuation

- Market and Intrinsic Valuation

- Comparable Companies

- Discounted Cash Flow

- Sum-of-the-Parts

- Net Asset Value

- Buyout Valuation

- Precedent Transactions

- Leveraged Buyout Analysis

- Accretion / (Dilution)

Market and Intrinsic Valuation

As outlined in Step II, comparable companies analysis (“comps”) lies at the heart of valuation. Key trading multiples for a company are calculated and compared to peers. This relative analysis helps identify whether a stock may be mispriced and represents a buying opportunity.

A more academic tool is discounted cash flow analysis (DCF), which values a company based on the FCF it is expected to generate in perpetuity. These cash flows, however, need to be discounted to the present. In essence, the multiples-based approach to valuation is shorthand for a DCF. The multiples are meant to capture the present value (PV) of the company's future cash flows.

There are several variations on the valuation approaches discussed above. For example, a sum-of-the-parts (SOTP) approach may be appropriate for companies with diverse business segments. SOTP values each segment separately using one or more of the techniques listed above. The values of the individual pieces are then summed.

Net asset value analysis (NAV) is similar to SOTP. It is typically used for companies that house multiple financial or physical assets under one umbrella. The analysis relies upon summing the market value of these holdings, less the company's liabilities.

Comparable Companies

For publicly-traded companies, the market has already established a valuation mark. Their shares trade on a public exchange where investors buy and sell them at a given price. Your job is to determine whether those shares are fairly priced, undervalued, or overvalued.

Comps is built upon the premise that public peers provide a natural reference point for valuation. This, of course, assumes that the market is properly valuing these companies. The first step is finding the right peer set. For some companies, this exercise is relatively simple. A large U.S. food and beverage company would naturally be compared to Coca-Cola (KO), General Mills (GIS), Kellogg (K), Kraft Heinz (KHC), and PepsiCo (PEP). For others, the exercise requires more creativity as there are no clear peers.

The peer companies are then benchmarked against one another based on metrics such as size, growth, profitability, returns, and credit quality. Sector-specific criteria are also added as appropriate. Their relative ranking provides clues as to why certain companies trade at a premium or discount to the group. Valuation is then framed accordingly.

In Exhibit 4.2, we benchmark Delphi vs. its peers. By now, detailed work on Delphi's business model and competitors enabled us to expand and refine the set of peer companies. We dissected them into groups of secular growers and production-linked auto suppliers. The constituents of each group are shown in Exhibit 4.3, where we display Delphi's detailed comps output page.

Trading multiples are at the core of comps, most notably EV/EBITDA, P/E, and P/FCF (or the inverse, FCF yield). Higher multiples are typically tied to higher performance and expectations. The savvy investor looks for a breakdown in these correlations. Perhaps the market is misreading growth prospects, cost-cutting initiatives, capital return opportunities, or other key catalysts. Your job is to assess whether the discrepancy represents an attractive opportunity.

Most of the time, the valuation disconnect is entirely justified. This is particularly true for so-called value traps. They have fundamental or structural problems that threaten to depress future earnings. So, a 15x multiple today may actually be 25x based on lower future earnings. As a close friend of ours likes to say: “Everything looks cheap as it's going to zero.”

Sometimes, however, you strike gold. The valuation discount jumps off the page—e.g., the company's growth rates are top quartile, but valuation multiples lag peers. In most cases, more nuanced analysis is needed. Otherwise, the market likely would have eliminated the arbitrage long ago.

EXHIBIT 4.2 Benchmarking Analysis

Now let's explore Delphi. Per Exhibit 4.2, its EPS growth CAGR was comfortably above production-linked comps and largely in line with the secular growers, albeit slightly below best-in-class BorgWarner. Its 12.7% EBITDA margin was also higher than production-linked players at 9.5% and approaching those of the secular growers. Further, Delphi's 20.5% ROIC was substantially higher than both peer category means.

Yet, as shown in Exhibit 4.3, Delphi traded at a significant discount to the secular growers peer set by all valuation measures—EV/EBITDA, P/E, and FCF yield. Its 2013E EV/EBITDA of 3.5x and P/E of 5x were relatively in line with the production-linked players, but multiple turns lower than secular growers who averaged approximately 6x and 11x, respectively.

Skepticism around the sustainability of Delphi's low tax rate from its UK incorporation likely helped fuel the P/E discount. In other words, investors were applying a haircut to future tax savings, thereby lowering their EPS estimates. This also manifested itself in Delphi's 15% 2013E FCF yield, which was markedly cheaper than the means of both groups. This was despite management's best efforts to highlight the sustainability of the company's tax benefits on the IPO roadshow and ensuing earnings calls.

In sum, Delphi shared a similar financial profile to the secular growers but was being valued like a production-linked player. The market was clearly skeptical of New Delphi's performance on a go-forward basis. Our work in Step III, however, gave us confidence that the new business model was working. With time and sustained performance, we believed the bankruptcy taint would dissipate and Delphi would re-rate higher.

EXHIBIT 4.3 Comparable Companies Analysis—Trading Multiples Output Page

Discounted Cash Flow

The basic premise of a DCF is that a company should be worth the present value of its future cash flows. This is known as intrinsic value given its basis in the underlying cash flows of a business. In this sense, the DCF serves as a helpful check on market-based approaches such as comps, which may be distorted during overly exuberant or bearish periods. It is also valuable when there are limited (or no) pure play peer companies.

In theory, a DCF should be the most accurate way to value a company. In practice, however, there are key considerations that limit its relevance and reliability. Most notably, it is highly dependent on assumptions regarding future FCF projections, which are inherently uncertain. Their uncertainty increases the farther out you go in the projection period. Additional assumptions regarding discount rate and terminal value further cloud the picture. As a result, the DCF valuation is viewed in terms of a range that is sensitized for key inputs, most notably discount rate and exit multiple.

Exhibit 4.4 displays the DCF output for Delphi.

EXHIBIT 4.4 Delphi DCF Analysis Output Page

FCF Projections A DCF is typically based on a five-year forecast, enough to carry a company through a business cycle and reach a theoretical steady state.1 The projections begin with sales or EBITDA and cascade down to unlevered FCF, or FCF before deducting interest expense. They are derived from management guidance (if provided), equity research, and third-party sources. Ultimately, you need to rely on your own company- and sector-specific diligence and judgment. The Delphi projections developed in Step III serve as the backbone for our DCF.

Terminal Value Given the difficulties in projecting a company's financials in perpetuity, a terminal value is used to capture cash flows beyond the five-year forecast.

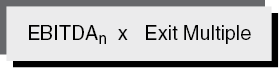

The terminal value is typically calculated on the basis of a multiple of the company's terminal year 2 EBITDA. This is also known as the exit multiple method (EMM).3 Standard practice for most sectors is to use the EV/EBITDA multiple for comparable companies (see Exhibit 4.5). For Delphi, we assumed an exit multiple of 5x, which was a blended average of the secular growers and production-linked peer sets, weighted towards the latter for conservatism.

EXHIBIT 4.5 Exit Multiple Method

Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) represents the rate used to discount a company's projected FCF and terminal value to the present. It is the “weighted average” of the required return on invested capital in the company, both debt and equity. WACC is commonly referred to as discount rate or cost of capital.

As shown in Exhibit 4.6, the WACC calculation requires several baseline assumptions.

EXHIBIT 4.6 Calculation of WACC

The percentage mix of debt and equity is based on an assumed long-term capital structure for the company. A typical mix might be 30% debt, 70% equity. In the absence of specific company guidance, look at its historical capital structure and that of peers.

Cost-of-debt is typically gleaned from the yield on a company's bonds. Depending on the interest rate environment, high-quality investment grade companies have yields in the low/mid-single-digits, while high yield bonds may feature coupons several hundred basis points higher. More speculative bonds yield north of 10%.

Cost-of-equity is more difficult to gauge. Pros use the capital asset pricing model (CAPM),4 a formula designed to capture the expected rate of return on a company's equity. Since inception, the S&P 500 has returned roughly 11% on average, including dividends. As with debt, cost-of-equity is higher for riskier companies, and lower for more stable ones.

In the low interest rate environment of the post-Great Recession era, a typical WACC was in the 7% to 12% range for most companies. Large-cap investment grade companies gravitated towards the lower end, or even below. More speculative companies were at the high end of the range, or greater.

For Delphi in 2011, we calculated a WACC of 10%. This relied on a 6% cost-of-debt (4.8% after-tax) based on its benchmark bond yield and a 12.5% cost-of-equity. We also assumed a long-term debt-to-total capitalization mix of 30%, implying 70% equity.

Present Value Calculating PV centers on the notion that a dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow, known as the time value of money. This is because a dollar generates returns over time through investments and earned interest.

For a DCF, PV is calculated by multiplying the annual FCF and terminal value by their respective discount factors. A discount factor is the fractional value representing the PV of one dollar received at a future date, given an assumed discount rate. At a 10% WACC, the discount factor for one dollar received at the end of Year 1 is 0.91 (1/(1 + 10%)^1). Therefore, the PV of $100 million of FCF produced in Year 1 is $91 million.

In practice, the PV calculation is adjusted to reflect the reality that FCF is generated throughout the year rather than at year-end. This is known as mid-year convention. Using mid-year convention and a 10% WACC, the discount factor for Year 1 would be 0.95 (1/(1 + 10%)^0.5). As shown in Exhibit 4.4, we used the mid-year approach for the Delphi DCF. For the terminal value, however, we used the full-year discount approach given the lump sum amount is assumed to be received at the end of the projection period. Note that the discount factor here is 0.62 vs. 0.65 for Year 5 FCF.

Putting It All Together

Enterprise Value The company's five years of projected FCF and terminal value are discounted to the present. The sum of these values represents enterprise value. For Delphi, the PV of five years of projected FCF summed to $5.2 billion (see “A” in Exhibit 4.4). The terminal year EBITDA of $3.2 billion was capitalized at a 5x exit multiple to provide a terminal value of $15.9 billion. This value was then discounted at a 10% WACC to its PV of $9.8 billion (see “B”). The PV of the future FCF and terminal value summed to an enterprise value of $15.1 billion (see “C”).

Equity Value is an easy calculation once you know enterprise value. Just subtract net debt, preferred stock, and noncontrolling interest. For Delphi, net debt of $818 million and noncontrolling interest of $462 million were subtracted from enterprise value of $15.1 billion to provide an implied equity value of $13.8 billion.

Share Price Next, you divide implied equity value by fully diluted shares. For Delphi, $13.8 billion of equity value was divided by 328 million diluted shares to yield a share price of nearly $42. This represented over 90% upside to the IPO share price of $22.

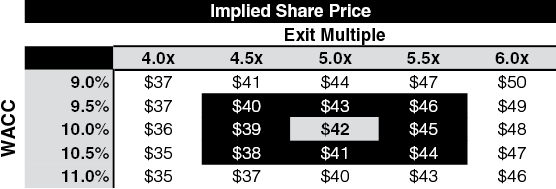

Sensitivity Analysis Given the multiple assumptions discussed above, the DCF valuation is viewed in terms of a range rather than a single value. This range is driven by sensitizing key inputs, such as WACC and exit multiple. Financial performance drivers may also be sensitized, most notably sales growth rates and profit margins. This so-called sensitivity analysis is a testament to the notion that valuation is as much “art as science.”

As shown in Exhibit 4.7, a half turn change in exit multiple equates to $3 per share of value. Likewise, a 0.5% change in WACC affects implied share price by roughly $0.75.

EXHIBIT 4.7 DCF Sensitivity Analysis

Sum-of-the-Parts

Some companies fall under the category of pure plays. Their business model is focused and relatively easy to label. The Home Depot (HD) and McDonald's (MCD) come to mind. On the other end of the spectrum are conglomerates, where a group of largely unrelated businesses are housed under one corporate umbrella.

Many companies fall somewhere in between. They have multiple business segments that may share similar inputs, materials, customers, and end markets, but with different growth and margin profiles. For these companies, it is often helpful to perform a SOTP that values each of the segments separately.

SOTP enables you to determine whether there is a valuation arbitrage between the whole and its parts. In some cases, you may find that the parts are worth meaningfully more than where the consolidated business is trading. This may signal a buying opportunity given the market's misinterpretation of the embedded value of certain segments. The spin-off or divestiture of one or more of these segments can serve as a catalyst to unlock this value.

A standard SOTP employs a comps approach to valuation. You find the best peers for each segment and then apply their multiples accordingly. This is the natural approach for valuing a division that is being contemplated for a spin-off. The values for each segment are then summed to arrive at an implied valuation for the entire company.

A “ mix-and-match” approach may also apply for SOTP. For example, your thesis may be for one or more segments to be sold. In this case, precedent transactions or leveraged buyout (“ LBO”) analysis can be used to value those pieces.

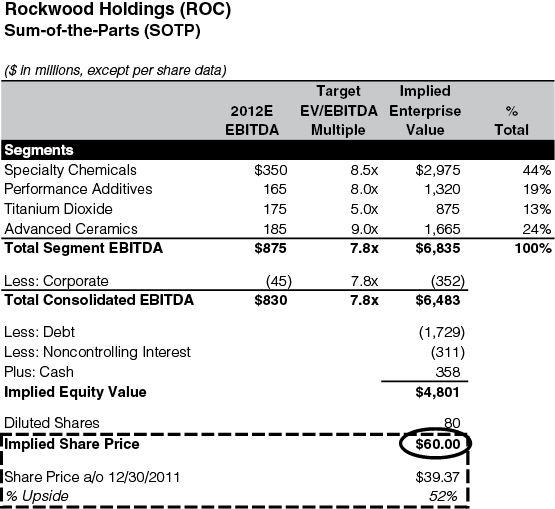

While SOTP wasn't particularly relevant for Delphi at its IPO, it did apply to Rockwood Holdings (ROC). In 2011, ROC was a leading global specialty chemicals company with four diverse business segments. As shown in Exhibit 4.8, ROC's SOTP at year-end 2011 yielded a $60 implied share price. This represented over 50% upside to its $39.37 share price at the time.

Over the next two years, Rockwood proceeded to sell its Advanced Ceramics and Titanium Dioxide businesses, as well as part of its Performance Additives segment. Then, in July 2014, the remainder of ROC was sold to Albemarle (ALB) for nearly $80 per share. All told, ROC shareholders doubled their money from December 2011. Clearly, the SOTP signaled embedded value that wasn't being recognized by the market.

EXHIBIT 4.8 Rockwood Sum-of-the-Parts

Net Asset Value

NAV analysis is traditionally used for businesses that house multiple distinct financial or physical assets. Common examples include Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs), oil & gas exploration and production (E&P) companies, and financial holding companies.

NAV is meant to reflect the market value of a company's assets, less its liabilities. For holding companies with stakes in multiple businesses, there may be a disconnect between the parent company's share price and the market value of its holdings.

Liberty Media (formerly, LMCA), which owned stakes in several public and private companies, is a classic example. Per Exhibit 4.9, in December 2012, LMCA's $105.56 share price represented an 11% discount to the sum value of its holdings at market value. Contributing factors included complexity, embedded taxable gains, tight trading liquidity, and ironically, uncertainty about how to collapse the public discount to NAV. Ultimately, the spin-offs of core assets Starz Entertainment, the Atlanta Braves, and the Sirius XM equity stake created substantial value for Liberty shareholders. Those who held on were rewarded with a 15% annualized return through 2019.

There also may be a disconnect between market value and stated book value for a collection of assets. This is often due to depreciation for accounting purposes vs. the asset's actual useful life, as well as the net effects of dividends and buybacks.

Liquidation value analysis, which is often employed in distressed or bankruptcy scenarios, is a variant of NAV. It seeks to calculate the selling price of a firm's assets under a liquidation or forced sale scenario. If the liquidation value is greater than the sum of the company's liabilities, then the remaining value is available for equity holders. Given the dynamics of a forced sale, liquidation analysis applies meaningful discounts to the market value of assets.

EXHIBIT 4.9 Liberty Media Net Asset Value

Buyout Valuation

Investors also examine valuation within a buyout or M&A context. They evaluate what a strategic buyer could pay for the company, often with specific acquirers in mind. They may also explore what a PE buyer can afford to pay for the business. Buyout valuation is particularly relevant for companies or sectors in play, where M&A is part of the investment thesis.

Key buyout valuation techniques include precedent transactions analysis (“ precedents”) and LBO analysis. Precedents derives valuation from multiples paid for comparable companies in prior transactions. LBO analysis examines the price a PE firm could pay for a given company and meet required return thresholds. For public acquirers, accretion / (dilution) analysis is also critical as it measures the pro forma effects of a transaction on EPS.

In theory, Delphi's modest valuation and low leverage post-IPO made a potential takeover feasible. In practice, however, the company's owners weren't in a hurry to sell given their perceived upside in the stock. Further, potential buyers were less likely to make aggressive M&A moves so soon after the Great Recession. More likely was an M&A scenario where Delphi would continue to upgrade the portfolio. This might include the sale of non-core businesses, or acquisitions to bolt on to its higher quality segments.

Precedent Transactions

Precedents, like comps, employs a multiples-based approach to valuation. The multiples used, however, are those paid for similar companies in past M&A transactions. As with comps, they are displayed in a format that allows for easy comparison and benchmarking.

Finding the right group of comparable acquisitions is the foundation for precedents. Like comps, the best comparable acquisitions involve companies similar to the target on a fundamental level. As a general rule, more recent transactions—those that have occurred within the past three years or so—are the most relevant.

Exhibit 4.10 displays auto supplier M&A transactions that were announced between 2009 and 2011. Given the global recession and muted M&A activity, there were few sizable large transactions and only one public company deal. The average EBITDA multiple paid was 6.5x, and 6x when adjusting for announced synergies. Synergies refer to the financial and strategic benefits that result from a combination, typically cost savings and revenue growth opportunities. These multiples were somewhat depressed vs. historical precedents given the time period, which straddled the Great Recession.

EXHIBIT 4.10 Precedent Transactions Output Page

Under normal market conditions, multiples for precedents tend to be higher than those for comps for two principal reasons. First, buyers generally pay a “control premium” when purchasing another company. This premium is typically in the 30% to 40% range, although it can be significantly higher. In return, the acquirer receives control over the target's business and future cash flows. Second, strategic buyers often realize synergies that support a higher purchase price.

Once you identify the best comparable acquisitions, you dig in on the specific circumstances and context for each deal. This enables you to better interpret the multiple paid and its relevance to your stock. Many factors affect the multiples for a given deal. Among these are the macro and capital markets environment at the time of the transaction, sale process dynamics, synergies, and whether the buyer was strategic or PE.

Buyer and seller motivations, including friendly vs. hostile situations, as well as the purchase consideration (i.e., mix of cash and stock paid to target shareholders) are also relevant. Typically, all-cash deals have higher premiums paid than stock deals. By receiving cash upfront, selling shareholders are compensated for bypassing the opportunity to participate in any future upside of the combined company.

Key Transaction Multiples

EV/EBITDA multiples are at the core of precedents with enterprise value based on offer price per share rather than current share price. As noted above, offer price typically reflects a significant premium to current share price. For particular sectors, such as banks, P/E and P/B multiples may be more relevant.

Investors often look at transaction multiples adjusted for expected synergies. This approach adds synergies to the target's standalone EBITDA, which serves to decrease the implied multiple paid and highlight the buyer's perspective (see Exhibit 4.11).

EXHIBIT 4.11 Synergies-Adjusted EV/EBITDA Calculation

Leveraged Buyout Analysis

An LBO is the acquisition of a company using a sizable amount of debt to finance the purchase price, typically 60% to 70%. The remaining portion is funded with an equity contribution by a PE firm.

LBO analysis is used by PE investors to assess valuation for potential targets. Stock market investors need to understand how PE investors frame valuation to determine whether a given public company may be a target (a.k.a., a “ take-private” candidate). In many cases, the implied LBO price serves as a floor valuation on a stock. This is also informative for assessing short positions given the inherent take-out risk for underperforming companies.

In practice, most publicly-traded companies are not viable take-private candidates. Any combination of size, price, business profile, ability to support high leverage, and actionability serve as potential impediments. Delphi's LBO viability was mixed. While its lagging valuation was attractive for suitors, its size, checkered past, and cyclicality were deterrents. Moreover, the 2011 market was still adjusting to the post-Great Recession world. So, the prospect of re-leveraging a recently bankrupt auto supplier was not top of mind for PE investors and financing sources.

Like the DCF, LBO analysis is based on a five-year projection model. However, there are additional complexities, including assumptions for purchase price, financing structure, debt terms, and exit multiple.

LBO leverage typically ranges from 4.5x to 6.5x debt-to-EBITDA depending on credit quality, sector, size, and market conditions. The structure and cost-of-debt also depend on these factors. For example, a more speculative cyclical business would have lower leverage and a higher blended cost-of-debt than a more established subscription-based business. The debt component is supported by a minimum equity contribution, typically at least 25% of the purchase price.

The exit multiple for LBO analysis is based on where comps trade on a mid-cycle or normalized basis.5 Once the cornerstone LBO assumptions are in place, you can solve for a purchase price that satisfies PE returns. PE firms typically target annualized returns (internal rate of return, or “ IRR”) in the mid-teens and higher, or a 2x cash-on-cash (“CoC”) return upon exit within five years. The exit takes place via a sale or IPO.

How Do LBOs Generate Returns?

LBOs generate returns through a combination of debt repayment and enterprise value growth. Regarding the former, assuming a constant EV/EBITDA multiple, a $1 decrease in debt increases equity value by $1. Per the latter, enterprise value growth may be a function of higher EBITDA or multiple expansion. In Exhibit 4.12, we illustrate how this works, including the IRR and CoC calculations. Let's assume the following:

- PE firm purchases a company for $1 billion, or 10x $100 million of EBITDA

- Acquisition is financed with 65% debt ($650 million) and 35% equity ($350 million), or 6.5x leverage

- Company produces $50 million of annual FCF for five years ($250 million cumulative), which is used to repay debt

- Company is sold for $1.5 billion at end of Year 5 (assuming constant 10x exit multiple on Year 5 EBITDA of $150 million)

EXHIBIT 4.12 How LBOs Generate Returns

After five years, the $650 million of initial debt has shrunk to $400 million as $50 million FCF per year has gone to repay debt. Given the $1.5 billion sale price and $400 million of remaining debt, the PE firm receives $1.1 billion of cash upon exit. Based on the $350 million initial equity contribution, the IRR is 25.7% (using the MS Excel IRR function) and CoC return is 3.1x.

Accretion / (Dilution)

Accretion / (dilution) analysis is critical for examining M&A-related stock opportunities. It measures the pro forma effects of a transaction on the acquirer's EPS using a given financing structure. If the PF EPS is higher than the acquirer's pre-deal EPS, the transaction is said to be accretive. Conversely, if the PF EPS is lower, the transaction is dilutive.

Yes, the headline price paid for the target is important, as is the multiple. But, investors' first question tends to be whether the deal is accretive and by how much. Dilutive transactions lower EPS or FCF/S, thereby reducing shareholder value (assuming a constant multiple). Consequently, acquirers shy away from dilutive transactions.

So, how does the math work? A rule of thumb for 100% stock transactions is that when an acquirer purchases a target with a lower P/E, the acquisition is accretive. This is intuitive. When a company pays a lower multiple for the target's earnings than the multiple at which its own earnings trade, it mathematically has to be accretive.

Conversely, all-stock transactions where an acquirer purchases a higher P/E target are de facto dilutive. Sizable synergies, however, may serve to offset this convention. Furthermore, if the transaction is largely debt-financed, the target's net income contribution often outweighs the associated incremental interest expense, resulting in accretion. Investors look for acquirers to maximize accretion by showing purchase price discipline, sourcing the optimal financing, and identifying significant achievable synergies.

Exhibit 4.13 displays a graphical depiction of an illustrative accretion / (dilution) calculation with a comparison of 100% cash (debt-financed), 50% cash / 50% stock, and 100% stock financing.

EXHIBIT 4.13 Accretion / (Dilution) Analysis

Catalysts

Catalysts are events with the potential to create shareholder value through higher earnings power, multiple expansion (a so-called “ re-rating”), or both. The savvy investor seeks to anticipate catalysts and the expected market reaction. This means initiating a position before a catalyst is announced or reflected in the share price.

Once a catalyst occurs, you must differentiate between a one-time share price pop vs. a more fundamental revaluation and long-term earnings ramp. The one-time pop might be due to an unsustainable short-term earnings bump (e.g., competitor dislocation or weather). Such pops are likely to be transient, subject to reversal in the following months. A fundamental revaluation would be premised on a stronger foundation—strategic M&A, portfolio realignment, major cost-cutting, shareholder-friendly capital allocation, or a blockbuster new product.

Below, we discuss catalysts within the context of anticipating events that promise to unlock value (see Exhibit 4.14). This stands in contrast to Chapter 1, where we screened for corporate events after they were publicly announced.

EXHIBIT 4.14 Catalysts

Catalysts

- Earnings

- Investor Days

- Mergers & Acquisitions

- Spin-offs & Divestitures

- Restructurings & Turnarounds

- Buybacks & Dividends

- Refinancings

- Management Changes

- Shareholder Activism

- New Products & Customers

- Regulatory

The Delphi investment thesis involved numerous potential catalysts—namely, earnings acceleration, capital returns, portfolio pruning, acquisitions, and a fading bankruptcy taint. The promise of next-generation products was also on the horizon. Astute investors could have gained confidence around the architecture put in place by the lead shareholders during the bankruptcy process, and that the active, highly accomplished Board would pull the right levers for value creation. Some catalysts came to fruition, some didn't, and some were welcome surprises.

Earnings

Upon announcing earnings, a company's share price may move up or down significantly. Why? Shouldn't the market have anticipated the earnings results within a somewhat narrow band? In most cases, the company is basically the same just after announcing earnings as before. So, what justifies such big potential swings?

The answer is simple. Companies are continuously evolving and striving to succeed in a competitive environment. At the very least, they are charged with delivering on their existing strategy. Earnings are a confirmation (or repudiation) of that strategy. In some sense, they are a quarterly report card for the company. Simply meeting expectations should produce a muted reaction from investors, while solid outperformance should be rewarded. Failure to deliver should be met with a strong rebuke, especially if there appear to be longer-term structural problems.

Suffice to say that earnings outperformance is central to any thesis. Solid execution and sustained earnings growth may be all that is necessary for a stock to be a big winner over time. A foundation of earnings compounders often serves as the backbone of a traditional equity investor's portfolio.

As a stock picker, you need to be able to compare quarterly earnings with prior year periods and consensus analyst estimates. In Step V, we provide analytical templates to facilitate this critical task.

Delphi's Q4'11 earnings release on January 26, 2012 was a critical one. It was the company's first post-IPO earnings report and its first time providing guidance. For the fourth quarter, sales were $3.9 billion (+6.8% y/y6), roughly in line with Street estimates. However, Q4'11 EBITDA of $530 million (+55% y/y) and EPS of $0.88 (+287% y/y) were massive beats, demonstrating management's strong execution and cost-cutting flow-through.

For the full year 2011, Delphi reported sales of $16 billion, EBITDA of $2.1 billion, and EPS of $3.49. These were sizable improvements over 2010 and well above Street expectations. The stock responded favorably, finishing up 4.7% for the day.

Companies also use earnings announcements to give or update guidance (if provided). Updates can take the form of confirming existing guidance or making revisions, whether upward or downward. In some cases, companies provide long-term sales or earnings goals, e.g., a 5-year sales target of $10 billion and 15%+ EBITDA margins. Typically, the guidance is more important than the actual earnings given the forward-looking nature of the equity markets. New guidance or revisions are important catalysts. Even a relatively small change can produce a large swing in the share price.

Beyond guidance, earnings calls provide management with the opportunity to announce major corporate events, new business developments, and changes in strategy that may serve as catalysts themselves. This new information is quickly processed by the market, which makes an initial assessment—the share price pops, drops, or remains largely unchanged. These new initiatives are then tracked over time by investors with the company held accountable for delivering on them.

Investor Days

From time to time, companies hold investor days to tell their in-depth story directly to current and prospective shareholders. These are typically large public events spanning several hours and can include product demos and facility tours (if held on site). They are led by the senior management team, often including division heads and business development executives. By the end of the investor day, attendees will have been presented with a comprehensive overview of the business and its strategic direction. A successful investor day can help reshape the company's narrative (if needed) and drive the share price higher.

Delphi held its first investor day in April 2012, only five months post-IPO. Going forward, the company elected to have an annual investor day to provide strategic updates, discuss capital allocation plans, announce acquisitions/new commercial endeavors, and provide guidance, as appropriate. In 2013, management laid out a plan to take EBITDA margins from under 14% to 16% by 2016. They also provided a long-term capital deployment plan earmarking 45% to 55% of operating cash flow for buybacks/acquisitions, 10% to 15% for dividends, and 35% to 40% for capex. The stock responded favorably, marching up 9.4% over the next two days.

Delphi's investor day in April 2016 was also noteworthy, setting forth goals for accelerated top line growth and EBITDA margins of 18.5% by 2020. Management also discussed the company's portfolio realignment strategy and announced the authorization of an additional $1.5 billion buyback. As with the 2013 event, Delphi's shares reacted positively, rising 6.7% over the following couple of days.

Mergers & Acquisitions

As discussed in Step I, various M&A scenarios can serve as meaningful catalysts. Event-driven investors and activists seek stocks where they anticipate M&A activity driving returns. This requires in-depth research on an industry to identify natural combinations, likely acquirers, and takeover candidates. Pay particular attention to sub-sectors where a recent takeover was done at a substantial premium. This often serves as a catalyst for peers to rally.

In May 2012, only six months after going public, Delphi announced the acquisition of FCI's Motorized Vehicles Division (MVL) for roughly $975 million. This represented 7x EBITDA and only 4.5x on a synergies-adjusted basis. Delphi's successful M&A execution was helped in no small part by Kevin Clark from the CFO seat. Clark had extensive M&A experience from his tenure at highly acquisitive Fisher Scientific—this proven skill set was fundamental to the Board's decision to recruit him to join Delphi in 2010.

MVL bolstered Delphi's already strong position in the high-growth, high-margin connectors market, while diversifying its customer base and expanding its Asia footprint. Financially, the transaction accelerated sales growth, enhanced overall margins, and was 5%+ accretive to EPS including synergies.

Delphi's share price rose 2.7% the day following transaction announcement and a further 5% the next trading day as the market absorbed the merits of the deal. By the end of 2012, the stock had increased nearly 38% since announcement date. Clearly, investors were pleased.

Three years later, in July 2015, Delphi was back at it again with the acquisition of public British cable management solutions provider HellermannTyton Group (LSE:HTY). The $1.85 billion purchase price represented 12.3x next twelve months EBITDA (9.1x synergies-adjusted) and a nearly 45% premium to HTY's prior day close. The high multiple paid reflected the strategic imperative behind the deal. HTY bolstered Delphi's already-strong position in electrical architecture, its largest segment. While the initial share price reaction was muted, the market eventually came around. By the end of 2015, Delphi's shares had risen 11% since deal announcement.

Along with the HellermannTyton deal, in 2015 Delphi disclosed several additional acquisitions/investments aimed at upgrading the technology in its product portfolio. It invested in a LiDAR sensing company, a software business focused on autonomous driving, and a tech company focused on fuel efficiency. Delphi was positioning itself at the forefront of autonomous driving, active safety, infotainment, and user experience.

Spin-offs & Divestitures

Investors often target companies with businesses or divisions they believe aren't being properly valued by the market. The basic premise is that the SOTP value of the two (or more) separate businesses is greater than the whole. In theory, separation should allow the market to assign a cleaner valuation to both the ParentCo and SpinCo, or DivestCo.

Ideally, you want to identify companies with potential spin-off or divestiture candidates early on. This enables you to participate in the upside upon announcement when the stock tends to pop. Many investors (including activists) specifically target these situations.

Part of the original Delphi investment thesis identified portfolio optimization as a potential catalyst, including the divestiture of non-core business segments. In this vein, in February 2015, the company announced the sale of its Thermal Systems segment to German auto supplier MAHLE for $727 million, or 9.5x EBITDA. Thermal had a lower growth and margin profile than Delphi as a whole. It also didn't fit with the company's increasing focus on secular growth areas. In the weeks leading up to announcement, Delphi's stock rose 9% as the deal was widely anticipated.

Two years later, Delphi executed another transaction, this one more transformative. In May 2017, it announced the tax-free spin-off of its Powertrain Systems segment, which was ultimately renamed Delphi Technologies and kept the DLPH ticker. ParentCo was renamed Aptiv (APTV, connoting knowledge, adaptiveness, and drive) and retained the higher-growth, higher-multiple Electrical/Electronic Architecture and Electronics & Safety segments. As such, Aptiv became a technology-focused pure play for investors concentrated on electrification and connected/autonomous vehicles. Meanwhile, Delphi Technologies would have a new management team and capital plan with the goal of reaccelerating top line growth and continuing to migrate up the value chain.

Upon spin announcement, the stock popped 11% and proceeded to advance 29% through year-end. Many sell-side research analysts had been assessing legacy Delphi on a SOTP basis for some time given the disparate growth and margin profile of its segments. Their analysis suggested that Delphi's parts were worth more than $100 per share, roughly 50% above the pre-announcement share price. Sure enough, the shares surpassed $100 before the spin closed in late 2017.

Restructurings & Turnarounds

Turnaround situations involve finding troubled companies with a viable path to redemption as the catalyst. Given the risks, your conviction in the revitalization strategy needs to be strong.

Delphi represented a classic turnaround. Its bloated cost structure, heavy debt load and legacy liabilities put the company into bankruptcy. This, in turn, led to underinvestment in the company's assets, which began to affect financial performance.

Under Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, Delphi's Board and lead shareholders worked with CEO Rod O'Neal to devise a strategy to reinvent the company. This involved pruning the portfolio, removing burdensome UAW contracts, moving manufacturing to BCCs, and a refocus on secular growth opportunities.

Once Delphi emerged in 2009, the turnaround didn't stop there. As noted earlier, the Board and management helped drive a continuous improvement and lean culture that permeated the entire organization. This relentless focus on operational improvements and efficiencies became ingrained in the culture. By the end of 2014, O'Neal's last full year as CEO, EBITDA margins were over 15%, a 200 bps improvement since the IPO. Under new CEO Kevin Clark, EBITDA margins expanded a further 200 bps reaching nearly 17% by year-end 2017.

Buybacks & Dividends

As discussed, companies with long-standing buyback or dividend policies can be attractive investments. The continuation of an existing shareholder-friendly capital allocation strategy, however, does not constitute a catalyst per se. A true catalyst relies on the anticipation of a dynamic new stock repurchase program or dividend policy. A material change in capital allocation can serve as a watershed event, sending the stock price soaring. Large programs are particularly interesting, e.g., annual buybacks representing at least 5% of the float.

Activist investors often focus on capital returns as a value creation lever. A typical target has a large cash position and no apparent urgency to deploy that capital. Upon accumulating a meaningful stock position (often 5% or greater), the activist pushes management to repurchase shares or initiate a large one-time or regular dividend.

For Delphi, buybacks loomed as a potential catalyst due to its strong FCF profile, active Board, and lead shareholders. In January 2012, just two months after going public, the company announced a $300 million share repurchase program alongside its Q4'11 earnings release. This was quickly followed by a new $750 million authorization in September 2012 when the market cap was roughly $10 billion. The stock popped 3.5% on the news.

Then, at its investor day in February 2013, Delphi announced the initiation of a regular quarterly dividend. Per O'Neal: “ Our strong balance sheet and significant cash flow generation allow us to take this positive shareholder action today. The initiation of the cash dividend, along with our existing authorized share repurchase program, continue to reflect our confidence in the business and commitment to enhance shareholder value.” Delphi's share price rose 9.4% over the next two days.

Refinancings

A refinancing can serve as a catalyst for revaluation. A common scenario involves an otherwise viable company that ran into trouble due to aggressive debt-financed expansion, a deep cyclical swing, or an overleveraged post-LBO capital structure. Shoring up the balance sheet serves as a catalyst for putting the company back on its feet. A distressed stock can turn into a big winner.

“ Clean-up” refinancings take many forms. Perhaps the simplest involves obtaining a new or expanded credit line that provides liquidity. Or, a transaction that replaces high cost debt with lower cost debt, thereby boosting earnings and FCF. Similarly, a company may extend its maturities by negotiating with current creditors or refinancing existing debt with new, longer-dated paper. In more extreme cases, a debt-for-equity swap can lighten the debt load while providing lenders a share of the upside.

Post emergence from bankruptcy, Delphi had a clean balance sheet with plenty of liquidity. Annual interest expense was reduced from $750 million in 2007 to $125 million at its IPO. In late 2011, Delphi's bonds were yielding 6%, which demonstrated renewed confidence in the company from the debt markets.

Management Changes

Some investors look for situations where a new C-level executive can serve as a change agent. The company may be undermanaged, misguided, or simply in need of new blood. Clear underperformance vs. peers is a typical telltale sign.

Simply targeting companies where a new executive could serve as a catalyst is insufficient. The change must also be actionable. Perhaps the current CEO is on the verge of retirement. Or, the Board has signaled it is ready to make a change. An activist, of course, might make a new CEO or CFO the core of its agenda.

An external hire is more likely to be an agent for transformational change. This is particularly true for restructuring and turnaround situations, which require a specialized skill set. Often, the change agent comes from within the industry and has a stellar track record. Perhaps most interesting is when the management change is driven by the Board or activists with a clear agenda for unlocking value in the stock.

We already discussed Rod O'Neal's CEO tenure at Delphi starting in 2007. Several years later, in September 2014, investors had the opportunity to reassess Delphi with the passing of the baton to Kevin Clark. As noted earlier, the Board recruited Clark in 2010 due to his “ high ceiling” potential. So, when the time came for O'Neal to retire, both the Board and investors had confidence in Clark as a worthy successor. Clark was expected to continue the focus on growth, operational excellence, and portfolio optimization.

As one research note summarized: “ Changing of the guard – Legend passes mic to humble rock star … we are very confident in Delphi's management team, led by Kevin Clark, whose disciplined approach to capital allocation and vision were instrumental in creating today's Delphi.” In this case, staying the course was a good thing.

Shareholder Activism

Activist investors don't buy a stock in anticipation of a catalyst and wait patiently. They take an “active” role in making the catalyst come to fruition. This is done by buying a sizable stake in the company and pressing for change. Prominent activist investors include Carl Icahn of Icahn Enterprises, Nelson Peltz of Trian Partners, Barry Rosenstein of Jana Partners, Paul Singer of Elliott Management, and Jeff Smith of Starboard Value.

While Delphi didn't have an activist per se, its investor base at the IPO included funds with proven turnaround track records and active investing approaches. Together, Silver Point, Elliott, Paulson, and Oaktree owned 45% of the shares. As large creditors in Delphi's bankruptcy, Silver Point and Elliott gained ownership of Delphi stock through converting their debt holdings into equity. Their longstanding intimate knowledge of the company and key governance controls enabled them to play a leading role in shaping the New Delphi.

Silver Point and Elliott played a direct role in working with management to develop and execute the new strategic plan. On the governance front, they assembled a world-class Board in 2009 with backgrounds comprising automotive, technology, operations, capital markets, and corporate restructuring. The new Board was granted a private equity-style mandate to actively drive shareholder value. This meant intense Board engagement (far exceeding typical public company Board standards) with substantial pre-IPO equity participation for the new directors. The equity packages strongly aligned the directors' incentives with the value creation goals of shareholders.

Silver Point and Elliott also recruited operating specialists to assist management with key transition matters, cost improvements, and the rationalization of underperforming units. In a critical move, the new Board brought in Kevin Clark as CFO, whose background included both private equity and public company experience. As noted earlier, Clark eventually became Rod O'Neal's successor.

The lead shareholders and Board spearheaded Delphi's strategy around capital structure, allocation, and monetization. In April 2011, they orchestrated the $4.3 billion repurchase of General Motors' stock holdings in Delphi. Just a few months later, they took advantage of the summer/fall 2011 European credit crisis to repurchase an additional $180 million of stock. These actions reflected a culture that was fixated on equity value creation and positioning the company for a successful IPO. Going forward, the Delphi team became their own activists in the best sense of the word—tireless and forward-thinking stewards of shareholder capital.

From a technical point of view, the eventual sale of the core shareholders' stock provided yet another catalyst. While Silver Point and Elliott did not sell their shares in the IPO—a particularly bullish signal on their view of the long-term investment opportunity—over time, their shares would move into the hands of long-term institutional shareholders. As a general rule, a more permanent shareholder base helps remove an overhang and re-rate the stock higher. Buying into high quality businesses when concentrated owners exit has proven to be fruitful over time.

New Products & Customers

The successful introduction of major new products can translate into material new sales and earnings. A true game-changer leapfrogs the competition without cannibalizing sales of existing products. Upon announcement, the share price typically increases in anticipation of a new growth leg.

Large customer wins are similar to new product introductions. A material new contract represents additional sales and earnings not currently reflected in consensus estimates.

At Delphi, new product introductions related to Safe, Green and Connected were core to its strategy. By 2014, Delphi turned its attention to autonomous and self-driving vehicles, showcasing its latest product capabilities at the annual Consumer Electronics Show (CES) in Las Vegas. These included a 360-degree radar and imminent collision automatic braking platform. Then, in 2015, Delphi became the first company to launch a coast-to-coast, automated driving trial.

Delphi's focus on higher-tech, higher-growth, and higher-margin new products was not lost on investors. Expectations for enhanced profitability helped propel Delphi's P/E multiple to nearly triple that at its 2011 IPO by 2017. This was previously a level reserved for blue-chip industrial companies, not old-fashioned auto suppliers.

Regulatory

Meaningful changes in the regulatory environment create both opportunity and risk. For example, the announcement of a new transportation or infrastructure bill should serve as a catalyst for aggregates, cement, and ready-mix concrete companies. Similarly, new auto emission standards provide an opportunity for suppliers to drive higher margin content per vehicle.

On the risk side, be mindful of particularly sensitive industries such as energy, financial services, healthcare, and media & telecom. In energy, coal companies were decimated by EPA regulations regarding greenhouse gases. At the same time, this created an opportunity for clean energy to fill the void.

Antitrust regulatory considerations are relevant across all sectors. The Department of Justice (DOJ) must approve all business combinations above $90 million.7 Therefore, any investment thesis or catalyst related to M&A activity needs to weigh the odds of receiving regulatory approval. The failed Comcast / Time Warner Cable (TWC) takeover in 2015 was a notable reminder.

Regulatory issues of a different kind thwarted Broadcom's (AVGO) $117 billion attempted takeover of Qualcomm (QCOM) in 2018—namely, national security. This deal was blocked on the basis of a recommendation by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS).

As previously noted, regulatory considerations were a key driver of Delphi's growth. In the company's core geographies, the implementation of increasingly tighter emissions and safety standards were catalysts. Each new standard was an opportunity for Delphi to introduce products and increase its content per vehicle. This also increased the company's stickiness factor with existing and new customers.

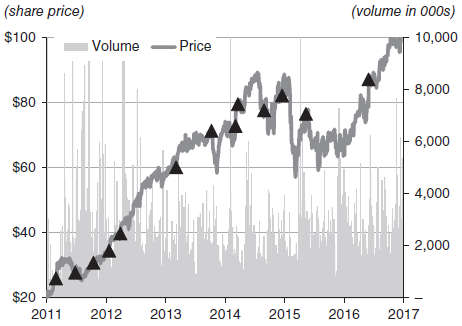

How Catalysts Drove Delphi's Share Price

All told, meaningful catalysts provided clear guideposts for Delphi's ascent, driving a nearly five-fold increase from the 2011 IPO through the 2017 spin (see Exhibit 4.15). They comprised a combination of earnings beats, M&A, buybacks, and dividends, as well as well-received investor days and strong long-term guidance. A successful CEO transition and spin-off transaction also supported Delphi's incredible run.

EXHIBIT 4.15 DLPH Annotated Share Price and Volume History

| ▲ Date | Reaction | Event |

| 1/26/12 | +4.6% | Reported Q4'11 earnings and released 2012 guidance, both beating estimates |

| 5/24/12 | +7.6% (2 days) | Announced accretive acquisition of FCI's Motorized Vehicles Division (MVL) |

| 9/13/12 | +3.5% | Authorized $700 m share repurchase program |

| 12/18/12 | +10.3% (6 days) | Joined S&P 500, pre- and post-addition buying |

| 2/26/13 | +9.4% (2 days) | At investor day, initiated quarterly dividend (1.8% yield) and laid out long-term capital allocation plan |

| 2/4/14 | +8.1% (7 days) | Reported Q4'13 earnings (beating estimates), and confirming FY'14 guidance |

| 9/9/14 | −0.3% | Announced CEO Rod O'Neal's March 2015 retirement and succession by CFO Kevin Clark |

| 2/4/15 | +7.9% (4 days) | Reported Q4'14 earnings (beating estimates), strong buyback, and raised FY'15 guidance |

| 2/19/15 | −0.3% | Announced sale of Thermal Systems segment to MAHLE Behr GmbH & Co. |

| 7/30/15 | +7.7% | Announced acquisition of HellermannTyton |

| 11/18/15 | +8.4% (6 days) | Presented at Barclays automotive conference, outlined expectations for strong year |

| 4/13/16 | +6.6% (2 days) | Held investor day and laid out 2020 targets of 8% - 10% revenue CAGR and 18.5% EBITDA margins |

| 5/3/17 | +10.9% | Announced spin-off of Powertrain and creation of new connected/autonomous-focused company |

Setting the Price Target

Now that you understand valuation and catalysts, how do you use this knowledge to pick a winning stock? Setting a price target (PT) is a critical next step. It is the culmination of your comprehensive due diligence and valuation work.

Your PT is the future price you expect a stock to reach if your investment thesis plays out. It is a core component of the ultimate investment decision, whether buy, short, track, or pass. Without it, you cannot properly quantify the upside potential and risk/reward trade-off.

The price target reflects the core market, intrinsic, and buyout valuation analysis already performed. This captures your financial projections and key catalysts. In many cases, the PT will be multiples-based, e.g., EV/EBITDA, P/E, P/FCF, or some combination thereof, with the closest comps serving as the main reference point.

In addition to your base case PT, you typically craft bull and bear cases. The risk/reward analysis is straightforward. Potential reward is measured by the percentage difference between the current share price and your base case PT. The bull case PT provides perspective on further upside potential. Your risk is reflected in the percentage difference between the current share price and your bear case PT.

Our PT analysis for Delphi is shown in Exhibit 4.16. We drove our base case PT off 2013E multiples for EV/EBITDA, P/E, and P/FCF. 2013E was chosen as the reference year for valuation as it allowed sufficient time for the auto recovery and Delphi's post-IPO strategy to play out. In other words, it reflected more “normalized performance.”

Consistent with our thesis that Delphi should trade in line with the secular growers, we assumed multiple expansion in our base case. For the base EBITDA, EPS, and FCF/S, we relied upon the financial projections laid out in Step III (see Exhibit 3.11). These same projections were used to run our DCF in Exhibit 4.4, which yielded an implied share price of roughly $40. This was helpful as a sanity check.

For P/E, our base case 10x 2013E EPS of $4.36 led us to a PT of $43.64, a 98% premium to Delphi's IPO share price. For EV/EBITDA, we used 6x 2013E EBITDA of $2.4 billion to produce a PT of $40.57. And, 8% FCF yield based on 2013E FCF/S of $3.26 implied a PT of $40.79.

Our bull and bear cases incorporated tweaks to assumptions for both financial performance and multiples. For example, the Delphi bull case contemplated faster top line growth led by better U.S. and China volumes, higher margins, and larger buybacks. This resulted in 2013E EPS of $5.50. Multiplying this by an aspirational multiple of 12x suggested a PT of $66, or 200% upside.

Turning to our bear case, we assumed weakness in Europe, lower U.S. volumes, and lower growth for China, as well as higher expenses. This yielded 2013E EPS of $3.75. For multiples, we assumed they would stay flat to Delphi's IPO levels, i.e., in line with production-linked players. Applying a 5x P/E to a lower-growth, less-profitable version of Delphi yielded a PT of $18.75, or 15% downside.

EXHIBIT 4.16 Setting the Price Target

Key Takeaways

- Before valuing a company, you must first understand its business and underlying financials

- Your valuation work needs to determine whether the stock is attractive at today's price

- Even a stock that passes the business and financial test with flying colors may fail the valuation test

- Growth expectations are critical for valuation—investors tend to reward higher-growth companies with higher trading multiples

- While a company's valuation may appear attractive, tread carefully—more often than not the stock is cheap for a reason

- Look for catalysts that can meaningfully re-rate a stock through higher earnings power and multiple expansion

- Earnings compounders that deliver year-in and year-out are the traditional stock picker's bread and butter

- Ultimately, your valuation work must yield a defensible price target, which is the basis for the investment decision

Notes

- 1 The projection period may be longer depending on the company's sector, stage of development, and underlying predictability of its financial performance.

- 2 Terminal year refers to the final year of the projection period.

- 3 An alternative approach is the perpetuity growth method, which calculates terminal value by growing a company's terminal year FCF in perpetuity at a sustainable long-term rate.

- 4 CAPM = risk-free rate + beta × market risk premium. Risk-free rate is the expected yield on a “riskless” security, typically a 10-year U.S. Treasury Note. Beta measures the covariance between the return on a company's stock and the stock market. Higher beta stocks are more volatile. Market risk premium represents the incremental return over the risk-free rate that equity investors expect to earn, typically ranging from 5% to 8%.

- 5 For conservatism, the exit multiple is generally assumed to be at, or below, the entry multiple.

- 6 y/y = year-over-year.

- 7 As of February 20, 2019, subject to annual revisions.