One-way ticket38

to return to his old job in IT. That paid €2,300 per month, so the

aloof and brooding Frenchman will need to keep working until he

is 177,569 years old to pay back his losses. If he takes no holidays,

that is.

s

Buys and sells

Outside the sky darkened. The mysterious Mr Conrad had fallen

silent but Anisa was still full of questions. ‘What does it mean

when investments don’t plot on the expected line of risk and

return?’

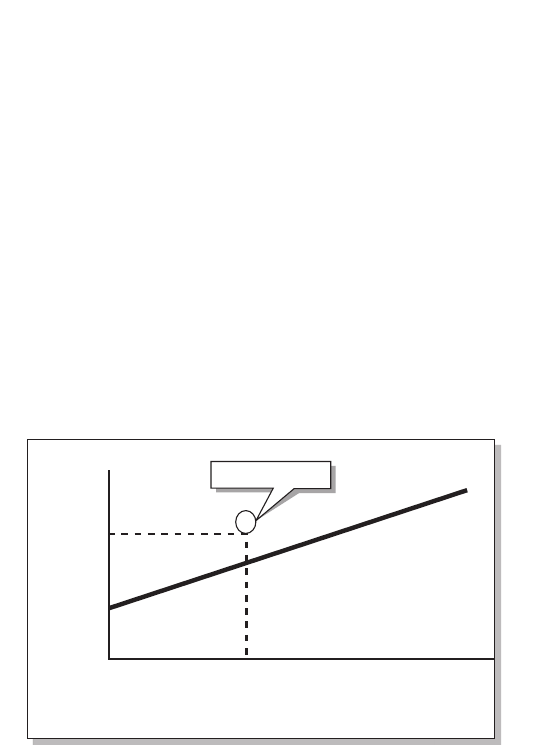

‘Look at the graph now. I’ve got Investment A and Investment

B. Neither of them can be plotted on the line of correlation.

How are they different and what is the message they send to

investors?’

Return

Low Medium

Risk

A

B

High

Attractive investments are found above the line

Anisa correctly rated Investment A as a strong buy. ‘I’d ll

my boots with it!’ she announced, to Conrad’s amusement.

39The leap of faith

‘Investment A is above the line. For a given level of risk, it’s giving

investors more return than they’d expect. You’ve got to buy it!’

I nodded at her to carry on.

‘If you buy Investment A before other investors do and they

follow you, their purchase orders will push the price of the

investment up until risk and return are aligned again. You

capture that price rise if you do good analysis, act early and

convince the market to follow you. If everything works, there’s

your capital gain.’

Anisa’s explanation was perfect, so I drew the two dotted lines in

her notebook.

Return

17%

8%

Low Medium

Risk

A

High

Above the line

‘You can see that most low/medium risk investments will give

you about 7 per cent return per year. But Investment A, which

has the same low/medium level of risk, is giving you 17 per cent.

Any investment which plots above the line is giving us more

return than the risk deserves. And that makes Investment A such

a clear buy.’

Investments below the line are to be avoided

‘Now, take a look at Investment B. Anisa, what do you reckon?’

‘It’s higher risk, but investors aren’t getting the return they deserve.’

One-way ticket40

‘Correct.’ I drew the two dotted lines on the ipchart.

Return

15%

6%

Low Medium

Risk

High

Below the line

B

‘Investment B is medium/high risk, so investors look for a return

about 15 per cent per annum. But the return is a paltry 6 per

cent. They should sell any investment below the line.

‘Bear in mind that investors can make money out of selling

investments as well as buying them. If they sell Investment B

before other people, and then other people follow them, then

the price will fall. What smart investors do now is buy back

the investment and return it to their portfolio. They have the

same investment but they’ve bought it at a lower price. So,

they’ve made money – or at least saved money – by the fall

in price.

‘A word of warning before you rush to set up your own private

trading oors. Both these approaches will only work when two

conditions are met. First, your analysis must be correct and,

second, enough people must follow you. The investment world

is littered with people who’ve done analysis which has been too

obscure, too complicated or too unpopular to be accepted by the

rest of the market. Or just wrong.’

Anisa asked a smart question. ‘What examples can you give of

Investment A and Investment B? I’m looking to make some fast

bucks when I get back to London!’

41The leap of faith

‘The sad fact is that investments don’t stay as A and B for long.

So, by necessity, my examples come from history.’

Many privatisations were above the line

‘Most government sell-offs are above the line.’ (We’ll look

at similar deals in more detail when I tell you about Jerry

Witts.) ‘The companies are normally well-established, with many

existing clients and very little competition. They are in steady,

dependable industries: electricity production, for example, or

water and gas. And governments are often very eager to raise

money quickly, so the shares tend to be below their true values

when the company is privatised. These sell-offs are usually low

risk and high return, so investors rush in.’

But football clubs are often Bs

‘Many football club shares are below the line. A football club

is always a very risky proposition because its fortunes largely

depend on how the team performs on the pitch. A company

may invest in loads of players and a new ground and then lose

every game. If it drops a division, the company’s income from

sponsorship deals, ticket sales and television rights will be vastly

reduced. And most clubs don’t make a prot, because player

salaries and transfer fees are often bigger than the company’s

turnover. The combination of high risk and low return puts most

football shares below the line.’

The sad case of Millwall Holdings

It’s one of my beliefs that we learn more from our mistakes than

our successes. Most investors take immense pleasure bragging

about their big wins. Delegates are often surprised when I openly

talk about my worst-ever investment.

case study

s

One-way ticket42

Millwall Football Club was based in an area of south-east London

best described as unfashionable. The most common words used

to describe the area were grim, dangerous and life-threatening.

Descriptions of Millwall supporters were even less flattering.

So imagine the excitement when the club opened a new stadium

closer to the centre of London and announced plans for a new

issue of equity capital. The club was pushing for promotion to

the lucrative Premier League and bought lots of good players,

including two Russian internationals.

I bought a line of shares at 2p each, which quickly rose to 4p.

I’d doubled my money in a matter of days. I reckoned that even

if Biblical plagues befell the club I would be in the money. How

wrong I was to be proved.

My share purchase coincided with a long string of defeats. One of

the Russian players was dismissed for alcoholism, after gleefully

admitting that he was on ‘a honeymoon which lasted for six

months’. The club dropped from promotion hopefuls to relegation

certainties. No games were shown on TV and ticket prices fell.

Sponsors and advertisers cut back dramatically, but the club was

contractually obliged to keep paying big salaries to its players.

Millwall entered administration.

The shares plummeted to 0.0181p. I didn’t sell them, though,

because the cost of a stamp and an envelope for the share

certificate was more than the worth of my total holding.

s

Day 1, 8.00pm – Nancy, France

Outside, oodlights suddenly shone through the sleet. Nancy

station was crawling with police.

‘I told you so,’ said Conrad. He’d predicted that we’d be held

up and was smugly happy to be proved right. It didn’t seem to

bother him that he’d be as late as the other passengers on the

train. ‘Where’s your rich friend got to?’

I shrugged. And that’s when I heard the scream.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.