One-way ticket34

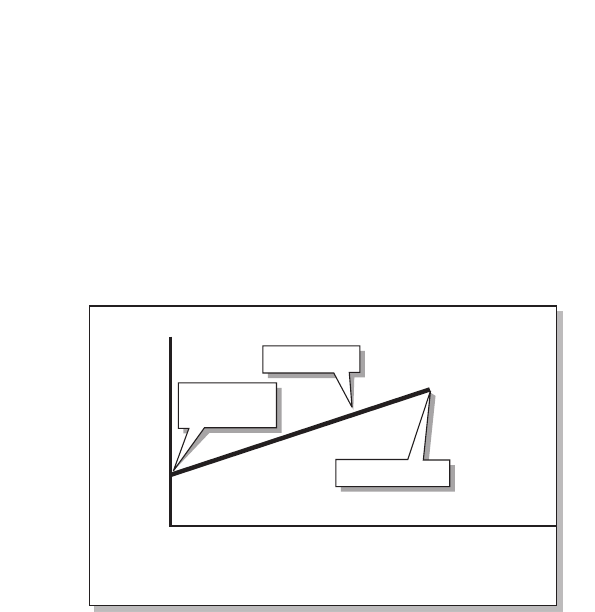

Riskier shares should offer more return

‘What about our luxury holiday company?’

‘It’s medium to high risk,’ she said. ‘Above the stable equity

but below the Russian oil company. I’d take a punt at 15 per

cent return every year. I reckon that will cover me for the extra

uctuations in the share price.’

Return

15%

Low Medium

Risk

High

Riskier share

Stable share

Government

bond

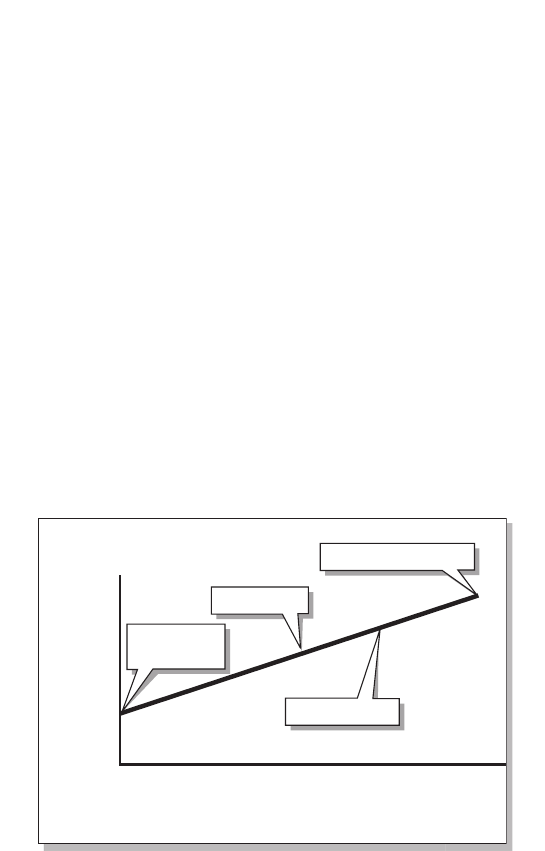

‘Your last choice is the Russian oil company. We all know that’s

super-risky, but if the return is high enough you’ll take a chance

and invest.’

‘It’s very risky,’ she said. ‘I’d need to get 25 per cent return every

year.’

Risk and return

I drew a line which linked up the four investments. ‘What do

you see?’

‘Risk and return are linked.’

35The leap of faith

‘And that’s the most important lesson you’ll ever learn about

investment decision-making. If you buy something that’s risky,

you should be compensated by the possibility of higher rewards.

But remember, it’s only the possibility.’

‘What does this mean in real life?’

‘If you want to make loads of money, you’ve got to be prepared to

risk losing your investment. But if safety is your main objective,

you’ll choose low-risk investments and have to accept a low

return.’

‘I see. Nothing ventured, nothing gained.’

‘That’s right. Risk and return are correlated. If you can’t afford to

lose your capital, you’ll choose the government bond and avoid

the riskier end of the market. If you can live with the idea of

losing your money, then you go in search of higher gains.’

Return

25%

Low Medium

Risk

High

Volatile investment

Riskier share

Stable share

Government

bond

Conrad opened an eye. ‘I would never invest in Russia. I’m too

cautious. I’d hate to lose all my money in some mad speculation.

I couldn’t sleep at night.’

‘But what about if the share offered 30 per cent?’

‘I still wouldn’t be interested. I want a steady income and I want

my money to be safe. I would rather miss out on a capital gain if

it exposed me to the risk of a capital loss.’

One-way ticket36

‘Forty per cent?’

‘You’re getting warmer.’

‘Fifty per cent return per annum? Surely it would be worth the

risk?’

Conrad shook his head. ‘OK,’ he said, but he didn’t sound too

convinced.

Day 1, 5.30pm – The French countryside

The sun was setting. Anisa yawned and there was a snarl on

Conrad’s face. ‘I think you made a classic mistake when you were

talking about risk earlier.’

‘What’s that?’ I asked.

‘You’ve tried to quantify risk. But risk isn’t an exact science. Risk

in nance means something you didn’t expect. And that must

include risks you’ve never even thought of, and have completely

ignored because you thought there was no chance of them

happening. Look at all the big brains there are in the investment

world, and look at all the mistakes they’ve made.’

Conrad took a sip of coffee before he continued. ‘Consider

the last nancial crisis. According to the experts it should

never have happened. But it did. Just because statistics say

an event is unlikely, doesn’t mean it’s never going to happen.

The world is full of things that are improbable, but come to

pass.’

‘Like what?’ asked Anisa, slowly stretching herself awake.

‘Like this train getting us to Paris.’

‘I was thinking more of a business example.’

‘Have you ever heard about the sad case of Jérôme Kerviel? He

was someone who was badly caught out because his assessment

of risk was wrong.’

37The leap of faith

s

Jérôme Kerviel – hero and villain

Kerviel lost €4.9 billion trading for the French bank, Société

Générale. His strategy was to buy shares, either directly or through

derivatives (Chapter 11 will expand your knowledge of derivatives).

His investments initially made great returns but the market turned

against him and the losses began to mount up.

Critics of Soc Gen say it was impossible for the bank not to know

about the trades. There were cries that Kerviel had been made a

scapegoat to divert attention from the bank’s weak controls and

poor management. Kerviel had very limited authority to trade and

it’s strange that he could do such huge damage in total secrecy.

By no means a star at work, the most interesting thing anyone had

to say about the small-town boy from Brittany was that he was

unremarkable or just like anybody else.

In court, Kerviel was described as taking risks that were inhuman

and stratospheric. He counter-claimed that Soc Gen turned a

blind eye to his trades as they were initially profitable. Kerviel

depicts himself in his book, Caught in the System, as a financial

crusader and a victim of social elitism. He became something of

a folk-hero amongst lower-paid employees in the financial world.

Presumably, they are all eagerly waiting for the movie which is

planned.

What’s clear is that Kerviel had no idea of how risk works. If his

trades had really been low-risk, it would have been impossible for

him to either make or lose large sums. The fact that he made large

gains should have alerted him to the possibility of big losses.

During his trial, a fellow trader attempted this analogy. It’s as if

Jérôme Kerviel had a mandate to buy 10 tons of strawberries but

bought 100 tons of potatoes and the supervisor passes through

the hangar every day and says nothing. With that sort of clarity

and logic in the dealing room, it’s no wonder that Soc Gen had

problems.

Weird fact – Kerviel was sentenced to five years in prison and was

also ordered to pay back the €4.9 billion. On release, he hopes

case study

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.