Engineer incentives

Energise everyone to be their best

Show me the incentive and I will show you the outcome.

Charlie Munger

BENEFITS OF THIS MENTAL TACTIC

Misaligned incentives are one of the biggest sources of organisational and relationship dysfunction. If you want to achieve great things, make sure you align everyone’s incentives.

The takeaway: your interests are not the same as other people’s interests, and no one cares about your interests as much as you. We’ve talked a lot so far about what to do – to articulate and frame your problems and identify and implement the right tools. Here we turn to the how questions that will allow you to get big things done. To accomplish your mission, understanding incentives is fundamental.

ENERGISE EVERYONE TO BE THEIR BEST

Your friend and their spouse have not been getting along for several years. There are no climactic arguments, just thinly veiled contempt that’s accumulated over decades of proximity. Your friend visits a lawyer for some advice about whether they should commence divorce proceedings or seek couples therapy. The lawyer notes that divorce proceedings will be drawn out and very expensive, but strongly recommends that your friend pursue this course.

You are selling your house and it’s on the market for $400,000. The first weekend that it is on the market, you receive an offer for $395,000 and are aware that there may be an offer from another party for $415,000, but that it will take a few weeks for the would-be buyer to make the offer. Your agent strongly recommends that you take the $395,000 offer.

You are the CEO of a major pharmaceutical corporation on the verge of retirement, and your compensation package is linked to the company’s share price performance. You become aware of the negative results of trials of your company’s newest drug. You can decide whether to disclose these negative results now, or have the next CEO do so in six months’ time, but you are fully aware that investors (not to mention doctors and patients) would benefit from knowing now that the drug is unlikely to be successful. You stall – the announcement becomes the next leader’s problem.

These three cases are all instances of misaligned incentives. Your lawyer doesn’t get paid if you get back together with your spouse; your estate agent takes such a relatively small percentage of the overall purchase price that they’d rather accept the lower offer than wait around a few more weeks for you to make a lot more money; what’s good for the pharmaceutical CEO isn’t what’s good for the investors or the company. A look at any organisation or relationship will reveal a misalignment in incentives somewhere. The problem – this misalignment can be extremely costly for at least one party and, over time, reduces trust, cooperation and the ability to get things done.

WHAT TO LOOK FOR: TWO BIG MISALIGNMENTS

Two categories of misalignment are the source of much of the organisational dysfunction you see around you: moral hazard and principal-agent problems.66

Moral hazard

What risks would you take if you knew there were limited negative consequences for you? The answer to that question encapsulates the problem of moral hazard: we take more risks when we feel protected from the consequences. As an example, you might be a little more careless about leaving a phone or a laptop on a table in a coffee shop if you know you have insurance against theft, or if the device belongs to an employer who will readily replace it.

The subprime mortgage crisis which engulfed the USA and eventually global financial markets from 2007 onwards is a larger example of this phenomenon. In retrospect, it was easy to see that many borrowers would be unlikely to be able to repay their loans. For the originators of the loans themselves, as well as the financial institutions that bundled them on to complex derivative products known as mortgage-backed securities, this risk didn’t matter too much. For many years, there were willing buyers of these loans and plenty of opportunity for the originators and bundlers to make a substantial return. For the individual Wall Street trader dealing in these instruments, their downside was strictly capped. At worst, they would lose their jobs, and at best they stood to make an enormous financial return. The systematic risk that these instruments created did not concern them – it was not factored in to their incentives.67

When people are protected from the downsides of their behaviour, and have the opportunity to enjoy a meaningful benefit, moral hazard will persist.

Principal-agent problem

A principal-agent problem arises when one person or entity (the agent) is allowed to act on behalf of another person (the principal). It seems sensible that the agent would have the principal’s best interests at heart in such a situation and would act accordingly. However, agents frequently have various competing pressures that prevent them from doing so. For instance, is a financial advisor recommending products offered by their institution versus another because it genuinely is the best product for the client, or because they will receive an additional commission for doing so?68

In our example above, is the lawyer urging divorce proceedings because they stand to gain financially from advising on a formal separation? It’s almost impossible to know, even for the lawyer themselves. But, once we understand incentives, we have an opportunity to design them more effectively.

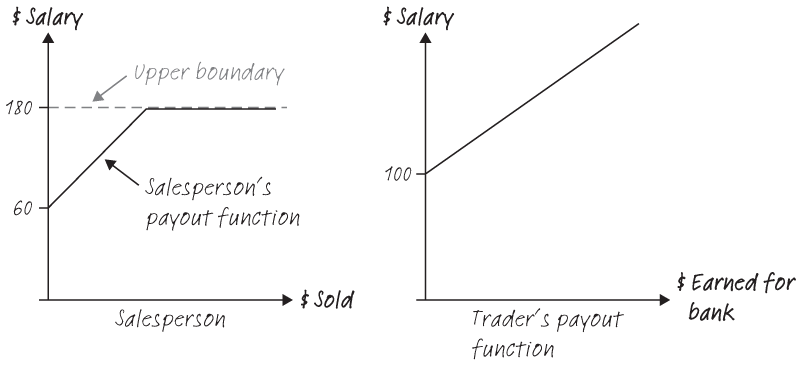

Imagine for a moment that you have a choice between becoming an investment banker (with a starting salary of $100,000 plus a bonus) and a salesperson (with a starting salary of $60,000 plus a bonus).

Not surprisingly, it is more attractive at face-value to be a banker – after all, your fixed salary is $40,000 higher. Now let’s look at the bonus element (what some organisations call ‘performance incentives’). The salesperson’s bonus is capped as they can never make more than twice their starting salary. Commission caps make some sense in that they prevent commissions from eating too far into profits. But they can also be counter-productive. Let’s say that this particular salesperson is particularly persuasive and efficient and by September has earned $120,000 in commissions. For the last quarter of the year, they have to keep coming into work, or they’ll stop earning their salary. But they also have no incentive to call a single customer, cultivate a new relationship or make an additional sale.

Now consider our investment banker. Like our salesperson, they earn their $100,000 salary no matter what, provided they keep coming into the office. But their bonus has no cap, and is linked to the short-term performance of their own investments and those of the company overall. Even worse, from an incentive perspective, a very large part of her success will be a function of luck and timing within the overall economic cycle. In such a case, the banker’s incentive is to take larger and larger risks – the downside is capped and their upside is theoretically enormous. The worst thing that could happen to our banker is that they earn £0 as a bonus – unlikely, and still not a very bad outcome considering they are guaranteed to earn $100,000.

The financial markets overall have a preference for stability: making sound, long-term investments and ensuring the smooth and efficient flow of capital. But the incentive structure for many of the actors in the system is completely at odds with this objective. Indeed, the misalignment of incentives and the desire for short-term performance above long-term stability has been identified as one of the contributing factors behind the 2008/9 global financial crisis. The phenomenon of packaging investments which paid big up-front fees, while ultimately creating longer-term losses even had its own acronym – IBGYBG (I’ll be gone, you’ll be gone).

DESIGNING YOUR INCENTIVE SCHEME PROPERLY

As always in The Decision Maker’s Playbook, we want to help you respond appropriately to the challenges we identify. Here, we are going to lay out our structure for designing appropriate incentive schemes.

CHECKLIST

How to break down incentives

ANALYSE INDIVIDUAL’S INCENTIVES AND LOOK FOR SIGNS OF NON-ALIGNMENT

ANALYSE INDIVIDUAL’S INCENTIVES AND LOOK FOR SIGNS OF NON-ALIGNMENT

What are people incentivised to do? Are the incentives aligned with those they are cooperating with? Are there ways that allow them to ‘game the system’?

TAKE ADVANTAGE OF LOSS AVERSION

TAKE ADVANTAGE OF LOSS AVERSION

Human beings are much more sensitive to the possibility of loss than the opportunity for gain.69 For instance, bonuses might be structured by telling the sales team that they have been awarded the maximum bonus on 1 January and that deductions will be made for lost clients or failure to meet targets.

IDENTIFY DIFFERENT OPTIONS TO USE THE SAME RESOURCES

IDENTIFY DIFFERENT OPTIONS TO USE THE SAME RESOURCES

For instance, how much of an employee’s pay should be variable based on performance (such as the product reaching the customer on time)? What metrics would you use? How do you avoid misalignment?

GOODHART’S LAW

We have seen that incentives can be reframed in ways that help us make a clear-eyed assessment of the situation. But what about situations where your incentives, no matter how well-intentioned, miss the mark entirely? Named after the Governor of the Bank of England who coined the phrase, Goodhart’s law refers to a situation where measuring a phenomenon causes performance to be distorted so much that the measure ceases to be useful. Or, as Goodhart himself put it: “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.”70

Driving the snakes out of India

To illustrate, let’s look at how the British tried to drive snakes out of India. The governing authority of the country confronted an infestation of cobras, including in major cities. This was obviously undesirable and the British turned to a predictable solution – bounty. Indian subjects would be paid for each dead cobra they could present to the authorities. On the face of it, this approach makes sense: you engage your community in shared ownership of the problem, you give them an incentive to reduce it and you require evidence (in this case, a handful of dead cobras) to demonstrate that the change has actually taken place.

In this case, as in many others, the policy actually produced the opposite of the desired change. In the end, there were many more cobras in India than in the beginning.

How and why? People responded to the outcome (produce a dead cobra) and the incentive (get some money) by changing the input – the enterprising subjects of the British Empire started breeding more cobras. This of course made it even easier for them to collect their incentives, but completely perverted the ultimate goal of the British policy. Realising the situation that they had created was untenable, the British ended the policy of paying bounties, but again trapped themselves with misaligned incentives. They had the same input problem (too many cobras) and their desired outcome was the same (more dead cobras), but the incentive had now switched (no cash for cobras). As a result, people did stop breeding cobras, but they also released all the cobras in their possession, thus compounding the original problem that the British had set out to solve.

By now, you can probably identify multiple examples in your organisations and teams of how these kinds of incentive problems arise. It might be the strict policy that requires workers to be at their desks until 5.30pm, but makes no distinction between the staff member assisting one more client and the employee shopping online for Halloween costumes for his pet. It might be the compensation structure that pays sales people huge bonuses for signing up a new customer, but doesn’t create any incentives for maintaining the relationship beyond the first sale.

WHY RATIONAL INCENTIVES FAIL

This is the point at which some of us despair. We throw up our hands and declare that all incentives are hopelessly misaligned, measuring things only makes it worse, and there are snakes everywhere. What can we do? One thing we definitely can do in a complicated world is to begin to take a good look at human behaviour and understand how people are motivated to take action.

The pizza, the money and the text message

To do that, we need to switch from India under the British Empire to present-day Israel in a semiconductor factory. Dan Ariely, a renowned behavioural economist at Duke in the USA (whose lab has the best name we’ve ever heard for a research institution: The Center for Advanced Hindsight) and bosses everywhere were keen to understand how to motivate production-line workers to increase productivity – to produce more in the same amount of time.71 Ariely divided the workers into four groups:

- A control group (more on them later) – they kept working as they had been.

- A group that was offered a pizza voucher when certain targets were achieved, on the assumption that we are highly motivated by free food.

- A group who received a cash bonus for achieving certain performance targets.

- A group who received a text message with a word of congratulation (good job“ or “nice work”) from a supervisor at the end of the day if targets were achieved.

Take a moment and make a prediction. Which groups increased their productivity? Which group’s productivity increased the most? One school of thought would suggest that the third group’s productivity should increase the most because people are responsive to monetary incentives. Assuming that the factory workers could increase their output more, they would do so. Pizza might work a little bit (because by eating free pizza, perhaps you don’t have to pay for lunch). But it should work a bit less well than cash, on the basis that not everyone likes pizza and not everyone likes pizza all the time.

Here’s what really happened. Pizza was the most successful motivator on the first day (maybe we do all love a free lunch). However, after a week, the strongest motivator was the congratulations text from a boss – beating the pizza and the cash.

There are a couple of things to love about this neatly designed study.72 First, it demonstrates that we are powerfully social creatures: we are extremely motivated by feedback from others, and it shapes our performance. Second, incentives even in an employment context, and even on a production line, may have nothing to do with cold hard cash or raw numbers. Instead, we can incentivise performance in others purely via recognition and appreciation. Third, we sometimes fall into the trap of thinking that incentives and motivation must be zero-sum games – they involve a transfer of resources (often money) from an employer to an employee.

Much time, effort and worry is invested in designing incentive schemes that an organisation believes will enable it to maximise performance and productivity with the smallest amount of incentives payment. Ariely’s study demonstrates that incentives (in this case, praise) can be completely free or extremely low-cost. And praise like this can actually maintain alignment of incentives over the long term:

- Business owners have an incentive to ensure that management is paying attention to performance, while also minimising the costs of creating that performance.

- Managers are nudged to pay attention to who is performing, but also to explicitly identify and appreciate that good performance.

- Employees have an incentive to demonstrate to management that they are achieving their targets on a consistent basis, and an emotional desire to be seen and appreciated.

CHECKLIST

How to turn irrational incentives to your advantage

SMS SOME PRAISE TODAY

SMS SOME PRAISE TODAY

This is one of our easiest tactics to deploy, with the highest payback. Pick up your phone (we know it’s close by) and text someone with your appreciation. As we’ve seen, it doesn’t need to be complex or detailed. Try: “I value what you bring to this organisation”, “I am grateful to have you on our team and just wanted you to know” or “Thank you for everything you do.”

MAKE IT A HABIT

MAKE IT A HABIT

Add a note to your calendar to text one person every day expressing your appreciation. Perhaps you work on a small team and are concerned you’ll repeat yourself? Don’t worry about it, remember Ariely’s factory workers. The messages keep working over time.

TRAIN YOUR TEAMS

TRAIN YOUR TEAMS

We are fond of suggesting that if you invested an hour a year in training for all your managers, it should be in learning to give clear, authentic and regular praise. Can you set aside an hour to do this with your team? Can you propose it to a leader in your organisation?

A FINAL NOTE ON EXTRINSIC MOTIVATION

As if snakes and pizza weren’t enough, we want to sound one final note of caution about using incentives to create extrinsic motivation. Extrinsic motivation is the kind that is driven by external rewards: money or fame are two good examples. Intrinsic motivation, as the name suggests, comes from within. We are intrinsically motivated to do things because it satisfies us personally. Intrinsically motivated behaviours are the kind we would do no matter what other people thought. It is often easier to practise intrinsically motivated behaviours because we want very deeply to do them. They can also often be complicated behaviours (helping others, persisting with difficult or complex tasks).

As leaders, it can be tempting to layer on additional extrinsic motivation to encourage people to do something. It can be particularly tempting when you need quick results: “We need more senior managers to mentor junior women,” or “We must have people spending more time doing advanced and complex testing of our software.” We have a tendency to underestimate other people’s levels of intrinsic motivation and instead assume that we will have to pay them to take action on this type of challenge. But just like us, other people are also motivated by the desire to do a good job, or have interesting challenges and positive relationships at work.73

In fact, a meta-analysis (a type of academic mega-study, where authors combine as many studies as possible on a particular topic and try to make sense of them) warns against this. Psychologist Edward L. Deci and 2 of his colleagues analysed 128 studies and made the following observations:74

- Offering monetary rewards can undermine our motivation for intrinsically rewarding tasks (something we find personally satisfying such as completing a difficult puzzle or giving advice). This is called a ‘crowding-out’ effect.

- This crowding-out effect is strongest for complex cognitive tasks – the kinds of things that take lots of mental effort, but can be highly worthwhile.

- Symbolic rewards (such as gifts or company awards) don’t have a crowding-out effect in the same way that monetary rewards do. Symbolic rewards may actually improve intrinsic motivation.

- The crowding-out effect is largest when the external rewards are significant (a big year-end bonus), are perceived as a way to control behaviour, require that the task is performed in a very specific way, or are associated with deadlines, surveillance or threats.

THE BOTTOM LINE

Incentives are tools to motivate individuals to perform actions. Misaligned incentives are one of the major causes of conflict and lost productivity in our world. However, careful up-front thought about the desired outcome, the relevant inputs and incentive system design can help anticipate and avoid common issues such as moral hazard, principal-agent and coordination problems. Pay attention to ineffective incentive systems and remember that intrinsic motivations may help you to change performance for the better, and for longer.