Multiply your possibilities

Use real options to improve your odds of success

Your task is not to foresee the future, but to enable it.

Antoine de Saint Exupéry, Citadelle or The Wisdom of the Sands (1948)

BENEFITS OF THIS MENTAL TACTIC

No matter if you’re trying to decide whether to build a new factory, buy a car or hire a new employee, you might benefit from the ability to change your mind. This tactic is useful when you have to make decisions with major consequences under uncertainty.

In uncertain situations, it is important to be able to switch between options when circumstances change. This flexibility, of course, typically carries a cost.

This mental tactic helps you to:

- consider future ‘optionality’: the ability to revisit and change your decision in the future

- calculate the costs and benefits of real options

- decide in which situations it is reasonable to purchase those options

- minimise the risks of bad or incorrect decisions

- maximise the number of choices you have at relatively low cost

- think about the value of information to make better decisions.

USE REAL OPTIONS TO IMPROVE YOUR ODDS OF SUCCESS

After Annie found the perfect apartment in Edinburgh, her landlord made her an intriguing offer. If she signed a lease over 24 months (instead of 12 months, which was the typical term), she could save £500 in rent every month. Annie had good employment prospects in the city, and she and her partner were planning to stay in the region for at least the next five years. £500 off her rent of £4,000 per month for 24 months would mean a benefit of £12,000 over two years. That’s a lot of money, but what if she needs to break the lease? What should Annie do?

Here we are introducing the idea of real options, a way of helping you evaluate or revisit decisions in response to changing conditions. We all make very material economic decisions, with very real trade-offs. Should we buy a house or rent? Should we purchase airline tickets today or wait to see if the price will go down next week? Should we pay a deposit for a private school for our child, knowing that we might get a new job in another part of the country next year? Should we invest in a new line in our factory even though we don’t have any new client orders yet? Thinking in options will help you plan for uncertainty, and stay flexible.

AN INTRODUCTION TO OPTIONS

Before we dive in, let’s do a quick overview of financial options.

“An option provides the holder with the right to buy or sell a specified quantity of an underlying asset at a fixed price (called a strike price or an exercise price) at or before the expiration date of the option.”63 Options are useful if you want to create certainty in your decisions. For example, you know that you will need some steel in four months’ time to construct a new plant but have nowhere to store it in the meantime. Instead of buying the steel itself, you can buy the option to buy the steel in the future but at a price that will be fixed today. That is, you can buy the steel, but you don’t have to – hence it’s an option. You pay a small premium to do so, but you’re buying an insurance policy that the price will increase beyond a level that you would find acceptable. In financial terms, this is referred to as a call option. The reverse of a call option is the right, but not the obligation, to sell an asset at a later date at a given price. This is referred to as a put option.

Let’s go back to Annie’s lease. Annie has given up optionality – the ability to get money back if she decides to move out before the lease expires, for a benefit of $500 per month. Should she do it? Let’s take a look at her options.

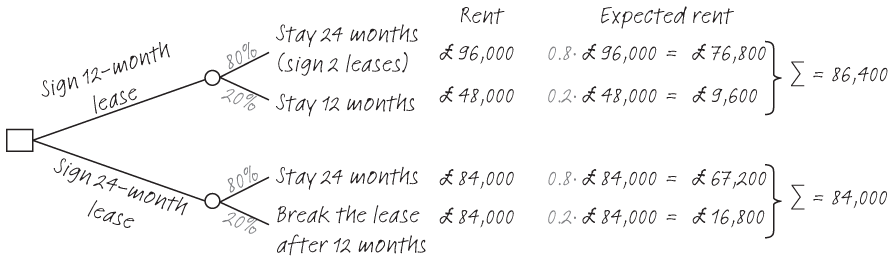

In the decision tree that follows, a rectangle symbolises a decision node, whereas a circle symbolises chance node.64

Whether or not Annie should take up the offer and choose the 2-year lease depends on her subjective probability of staying for 12 or 24 months. Let’s assume she estimates the likelihood of staying for two years at 80% and one year at 20%.

With these likelihoods, Annie should indeed sign the 24-month lease as it will save her £2,400 (£86,400–£84,000). To put it a different way, Annie is being paid £12,000 over the course of 24 months in exchange for her to give up the option of leaving after 12 months. Given Annie’s subjective probabilities, signing the 24-month lease will improve her situation by £2,400.

Option value not only plays a role when renting, but also when buying properties. In many jurisdictions in the USA, when buying a house or apartment, one pays a relatively small deposit (for instance, $1,000) to hold the property for, say, three days, in order to conduct the necessary due diligence. Should you decide not to buy the property, the seller gets to keep your $1,000. In that instance, you’re choosing the option to buy the property at a later date at an agreed price, and preventing anyone else from buying it.

Sometimes you can obtain these options at no cost, depending on your negotiating power. Here’s a trivial example. On a Saturday morning, you’re out shopping for a new outfit for a party that night. You’ve tried on some clothes that you like in the first shop you go into (this should be a clue that Simon and Julia are old souls, we’re still trying on clothes in real shops). But you don’t know if they’ll be your favourite as you might see any number of other terrific outfits during the day. So you ask the sales assistant to hold the items for you until 3pm, and they agree to do so. At this point, you’ve acquired an option – you have the right, but not the obligation, to buy those items at the price on the tags any time before 3pm on Saturday. Cleverly, you’ve managed to obtain this option at no cost to yourself, but at some inconvenience and risk to the store’s staff and owners. They have to store the items securely for you, and politeness dictates that they don’t sell them to anyone else. If you decide not to exercise your option, you simply don’t return to the store and at 3:01pm, the items go back on the sales rack.

This simple example is actually the exception. Options almost never come for free. Consider the case of Alex and Danny, a couple with two children under eight. Each of them have busy full-time jobs and a variety of other commitments. Four months ago, they realised that they spent almost no time together. So, Alex proposed a creative solution that they would reserve a babysitter every Friday night. If they felt like going out to the movies or for dinner, the babysitter Matt would be on their doorstep at 7pm. But if they felt like staying in for a family dinner, and so cancelled on Matt, they would still pay him. They had to, they determined, in order to ensure that Matt would be available on the Friday nights that they did want to go out.

USING OPTIONS IN YOUR DECISION MAKING

Once you start looking, options are all around you. Understanding how to multiply and maximise your options becomes a useful tool in your decision-making arsenal. We’re going to introduce three types of options that we think are particularly helpful as you make a decision: the option to expand, the option to delay and the option to abandon.

Option to expand

The first category is the option to expand, to effectively double or triple down on your current decision at some future point. For example, executives at a manufacturing company may not know if the company will need to expand its production facilities, but they know it would benefit by having the option to do so in the future if demand for its products increases. By purchasing additional land near its factory today, they can create the option to expand tomorrow if that turns out to be the right move. If it doesn’t make sense to expand, they can simply sell the land or lease it to someone else. Options give leaders the ability, but not the obligation, to revise a decision in the future if it proves to be beneficial.

One other place you see decision makers establishing their option to expand is in the dying moments of a film, where a cliff-hanger conclusion sets up the possibility for a sequel. Take the dying scenes of Roland Emmerich’s Godzilla. Even after the world has been saved, we fade out on the image of one of Godzilla’s eggs cracking open. The world is safe … until the sequel.

Option to delay

The option to delay is fairly self-explanatory. It’s the right to undertake a project in the future, while not committing to undertake it today. You can also think about the option to delay in relation to employment relationships.

During the 2009 global financial crisis, some professional service firms practised a variant of the option to delay in relation to their new hires. US law firm Skadden Arps had hired associates (entry-level lawyers straight out of law school) but the market for top-tier legal services had slowed to such an extent that it didn’t make sense to bring these associates on board right after their graduation. However, the market hadn’t slowed so much that it made sense to tell the associates to start looking for another job. The Skadden Arps partners were, in effect, looking to buy time. They did it by offering the would-be associates 50% of their first-year salary ($80,000 at the time) in return for starting work a year later. During that time, associates could travel or write the Great American Novel or anything else, secure in the knowledge that they would have a job at the firm in a year’s time. Meanwhile, the firm could manage its payroll costs by exercising its (admittedly costly) option to delay.

Consider too the case of a film producer who reads a book that deeply moves her. She senses that this story deserves another audience and envisages that it would make a wonderful film. She buys for a fairly nominal sum (authors are not so well-paid) the rights to the movie. The producer is buying an exclusive option. She has purchased the right to make the movie, but also the right to delay making the movie until she is ready – or to never make the film. But while she holds the option, she prevents other producers from making the film.

There is another category of real options known as the option to switch. The option to switch is effectively the right to press pause on a project or commercial operation (for instance, because the political or security situation in the market deteriorated) and then to resume it again when certain conditions are met.

Option to abandon

The third category of options is the option to abandon – to withdraw your involvement in a project at a certain point, or when given conditions arise. Employment probation is one practical illustration of an option to abandon. Say Simon hires Julia as a new operator for his 3D printer. While Simon is excited about the possibilities of 3D printing, he’s not sure that he can build a real business out of it. So Simon adds a clause in the employment agreement specifying a 90-day probation period, at which time the employment relationship will be evaluated and confirmed, or not, at his discretion.

Through the probation period, Simon is giving himself the option to abandon: the ability to discontinue the employment relationship at no cost to himself or his company. Temping agencies, which provide staff on short-term contracts to employers, possess similar flexibility. An option to abandon is far simpler to exercise than dismissing a traditional employee.65

To return to our retail examples from earlier, think about companies who offer free shipping and returns on products purchased online. The company is effectively providing you, the consumer, with a free option to abandon the products within a set period (often 30 or 60 days) if you find them unsuitable or unsatisfactory. In some cases, companies will ask you to pay for the return shipping on an item if you decide you don’t want it. In exchange for the option to try the item on in the comfort of your home, or test it alongside the rest of your decor, you are effectively acquiring a put option. You are paying for the right to sell the items back to the retailer at the agreed price, minus the cost of shipping. In order to have these items in your home, you agree to accept the possibility that you might not like them enough to keep them and will have to pay to return them.

MAXIMISING OPTIONS

One of the goals of leaders should be to help organisations multiply their options – to an appropriate extent. Too many options and you can become paralysed when trying to make a decision. Too few and you may be cornered into a course of action that doesn’t work for you.

The two of us give lots of advice to people early in their careers. Often, the dilemma that young people are facing is how to pick a first role (or company or industry) while they are very uncertain about their own preferences, and painfully aware of the ever-changing nature of the world of work. In such instances, we typically encourage people to think in terms of options, no matter what stage of their career they are in.

Early on, where uncertainty is high, we encourage people to maximise the number and range of their future options by taking jobs that expand future possibilities, rather than foreclosing them. This might mean, for instance, pursuing a management training programme in a large company, with opportunities to try on different roles in different functions, including finance, marketing, product development and so on. By taking on such a role, a graduate is effectively buying themselves an option to pursue a range of future careers, without foreclosing any of them.

A NOTE ON BAD OPTIONS

We’ve advocated maximising your options in a whole range of settings. We’ve argued that where uncertainty is high, flexibility is king. As always, this is true only to a point. There will always be bad options which are too expensive or complex to justify the effort. For us, the classic example is travel insurance. It is a costly investment, where the ability to exercise your right to compensation is typically confined to a very limited set of circumstances. Now, while travel insurance can provide financial compensation for disruptions, it cannot give you back what you probably wanted in the first place – a smooth holiday experience, or the ability to arrive at your board meeting on time. Not all options are a good deal, and not all options give you the flexibility you are seeking.

CHECKLIST

How to be smart with options

BE CLEAR ABOUT THE TYPE OF OPTIONALITY YOU ARE SEEKING

BE CLEAR ABOUT THE TYPE OF OPTIONALITY YOU ARE SEEKING

The investment approach to thinking about options is helpful in other contexts too. Be specific about the kind of optionality you are seeking, such as:

- certainty about a price or a circumstance (minimisation of the downside risk of price increases)

- the ability to wait and make a decision at some point in the future

- the ability to cease a new project if it just isn’t working.

DETERMINE WHAT YOU’RE PREPARED TO PAY FOR CERTAINTY AND FLEXIBILITY

DETERMINE WHAT YOU’RE PREPARED TO PAY FOR CERTAINTY AND FLEXIBILITY

Knowing that you want an option is only half the battle. Determining what you might be prepared to pay for optionality is the other half, and what someone is prepared to pay to extend that flexibility to you. $1,000 might be a very reasonable sum to buy a house in three days. $1 million might be the price to keep the land next to your factory empty for five years, before you can decide whether to build on it.

USE A COSTS AND BENEFITS TREE TO ROBUSTLY ESTIMATE THE TOTAL COST – AND THE VALUE OF YOUR OPTION

USE A COSTS AND BENEFITS TREE TO ROBUSTLY ESTIMATE THE TOTAL COST – AND THE VALUE OF YOUR OPTION

Real options are conceptually much more than mere alternatives – they are a way to place a quantitative value on those alternatives. Once you’ve generated your options, draw them out and assign values.

PUSH YOURSELF TO ENSURE THAT THE OPTIONS OR INSURANCE YOU’RE TAKING ON ARE REALLY WORTH IT

PUSH YOURSELF TO ENSURE THAT THE OPTIONS OR INSURANCE YOU’RE TAKING ON ARE REALLY WORTH IT

There are some instances where the options we take out are not worth it. Overpriced insurance is a classic example. Taking on extra staff to prepare for a rush that may not arise is another. Waiting around for a better job offer that may never materialise is a third. You can ask yourself:

- Would I truly exercise this option?

- If the event I am insuring against never arose, would I still be happy I had the insurance?

If the event did arise, would the insurance be sufficient to compensate me? In the case of travel insurance, for instance, the payout might be enough to get you where you are going, but can’t repair a missed vacation – so perhaps the money does not matter.

FURTHER EXAMPLES

Buy or rent?

When you start to look, you will see options all around. The choice to buy or rent is one such example. Let’s assume we have a would-be householder who could afford to either rent or buy the home of her choosing. When she rents, she gives up the ability to control the property and to earn capital gains if it appreciates in value for the flexibility to leave the property in the near future – the option to abandon – if it doesn’t suit her needs. Let’s say she goes one step further and takes out a month-to-month lease. She potentially pays a little more but is free to leave the apartment with just 30 days’ notice if conditions change.

Flight or flex?

The often mysterious world of airline pricing is replete with options. If you purchase the lowest-cost fare, you are often giving up all of your options in exchange for a cheaper ticket. This includes the option to delay (by moving your flight to another day or time) and the option to abandon (by cancelling your flight for a refund). Buying a flexible fare gives you back these options – for a price.

Some airlines provide what is known as a seat guarantee for their most frequent flyers. The guarantee represents a promise that the frequent flyer will be able to obtain a seat on any of the airline’s flights, including full ones. They are effectively giving you a permanent option to acquire a seat on any of their flights as a thank you for your loyalty – and all of your previous (and, they hope, future) spending. You’ll notice that exercising this option is likely to result in another passenger without this option being summarily ejected from the flight.

Mind the gap (year)

US President Barack Obama’s eldest daughter Malia made headlines in 2016, when the White House announced that she would be taking a gap year before commencing university study. A gap year – where young people might travel, work, or volunteer – can be seen as an option to delay. The student’s university of choice gives the student the right to be admitted a year later than they would have otherwise planned (also an option to delay). In this case, the option is rather one-sided – the student still has the option to try to be admitted to a different university on the same timeframe or even to decide that continuing to study isn’t for her at all and exercise the option to abandon at no cost.

THE BOTTOM LINE

Having the option (but not the obligation) to act in the future is valuable, particularly in environments that change quickly and unpredictably, and that are hard to shape or influence. Options are everywhere you look. Understanding and valuing options is an important skill to hedge for future contingencies. Your goal should be to create and use them wisely to enable optimal decision making in the future. Remember, a truly valuable option hardly ever comes for free. Start thinking about your future choices as today’s options, each with a value attached.