3

Communication Renews Rationalities

3.1. From agent to actor

The coordinated valorization of the physical goods and functionalities that fundamentally underpin the service contracts of the functional economy implies, in our opinion, that territorial value analyses are carried out according to the three levels of interrelated decoupling that we have mentioned. These three levels of decoupling, each referring to more intangible – but just as “material” – assets than those described by the previous level, should be seen in relation to the five forms of work introduced at the end of Chapter 1.

The production considered at the first level of decoupling is that which implies that social work induces a new form of economic work (recognition of social and ecological phenomena), leading to a form of industrial work that is less constraining for ecosystemic work.

The production considered at the second level is that by which social work, again, opens the territorial horizon of production to the arrangement of physical goods turned toward multifunctionality, and thus induces the constitution of an ecosystem of actors dedicated to maximizing the value of their use.

The production described at the third level of decoupling implies that social work allows, always, through the valorization of the use of the multifunctionalities produced, a renewal of the view on the question of exchange value (valorization between intangible service entities) leading to new selections of industrial working methods through financial work.

These relationships between work components and levels of decoupling constitute a useful framework for structuring technical and socioeconomic relations between entities, thus for a territorial information system, and thus for the institutionalization of functional ecosystems.

Insofar as they are necessary for the recognition of common or reciprocal interests, these relationships have capital value for the entities of the territory, considered individually and jointly. Considered together, these relationships have a territorial heritage value.

3.1.1. Decompartmentalizing the economic space

3.1.1.1. Socio-technical system and monetary representation

For Gaudin (2001), “It can be noted that the relatively recent mobilization of the actor category has been part of three major scientific issues. The first focuses on the objectification of what is observed. […] The second is the relationship between individual and collective actions. […] Finally, the third is the choice of methodological paths, an issue that is difficult to separate from the previous one. […] Here again, the use or not of the notion of actor, the place it will be given in the characterization of the observed phenomena, appears to have serious consequences.”

The challenge of building a territorial information system is precisely to enable people to be actors in social, economic, industrial and financial work, not only agents predetermined by a context that is imposed on them and shapes their representations and actions.

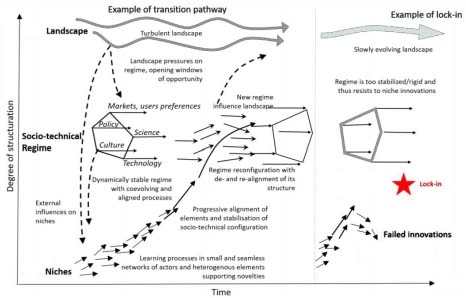

The functional ecosystem within which the co-production of product– service offers takes place is, more broadly, part of a sociotechnical system that Geels (2002) breaks down into three articulated levels: the “landscape”, the “regime” and the “niche”.

The niche allows the emergence of disruptive innovations and their gradual maturation, sheltered from the selection pressure exerted by the regime of which it is part. The sociotechnical regime is characterized by norms, beliefs, cognitive routines and regulations, all of which, more or less stable, guide the trajectories of practices. The landscape describes the environment exogenous to the regime, composed of macroeconomies, cultural representation models and macropolitical developments (Bernard de Raymond and Goulet 2014).

If the articulation between these three levels is broken, then the sociotechnical system is “locked”. This is the case if a niche innovation cannot influence the cultural, political, economic, scientific and technological regime of which it is part and which is likely to propagate it, or if the diversity and dynamics that characterize the sociotechnical landscape are too low to accompany the evolution of niches and regimes.

Figure 3.1. The multiple view of transitions. Adapted by Ollivier et al. (2018) from Geels (2002)

In a functional economy logic, presented in Chapter 2, if we refer to Geels’ sociotechnical system, the collective innovation that gives rise to a product–service system (PSS) is constituted at the level of the niche. We have described the influence of a functional ecosystem on the spread of PSS innovation, both through concerted specialization among stakeholders and through shared representations of the functionalities produced and their values. This ecosystem is built up at an intermediate level between the niche level and the Geels regime.

In short, a service offer backed by a multifunctional niche production is only recognized as valuable if it is based on a performance evaluation capacity that is very contextualized because it is influenced by a regime. The practice of valuing service offers is therefore inseparable from the sociotechnical environment of their collective construction. In other words, the very action of this construction produces representations of performance that only occur locally, within the functional ecosystem.

The financial value of a service is therefore not only related to the availability of useful functionalities, as suggested by the comparison of assets and liabilities that we indicate in the third of the decoupling levels discussed in Chapter 2. It also depends on fluctuations in the demand for market solutions based on access services to these functionalities, and therefore on fluctuations in the non-market response capacity to the demand for utilities considered at the second decoupling level. This fluctuation is therefore not only due to a fluctuation in need but also to a variability in the capacities to identify and recognize these functionalities, their values and the access modalities that allow their use to be made available.

The difficulty in monetizing a service based on multifunctional production is that the functional ecosystem is an open system. It is part of a regime and subject to the influence of several niches as well as to the major trends in the socioeconomic landscape. The multiplicity and cross-fertilization of these influences induce different levels of needs formulated by actors who do not have the same representation of the values of functionalities, or the same capacity of access – commercial or not – to their use.

In other words, the fact that the use value of a multifunctional production is correlated with the market value of the services for accessing the functionalities it delivers could only be due to an exceptional situation of high market structure offering opportunities for all the utilities that can be recognized for this production. This reduces the solvency potential of the entities that make up a functional ecosystem whose choices of ecological sustainability and functional response to social needs are not associated with monetizable services.

Moreover, a disconnection between different areas of representation of functionalities, their values and the modalities of their availability reinforces this obstacle to the emergence of multifunctional productions that are socially and ecologically sustainable without being monetizable.

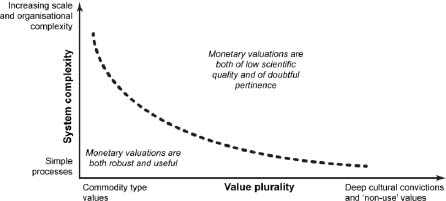

For Frame and O’Connor (2011), any monetary representation approach loses its quality and relevance when value objectification processes involve analyses of complex systems based on the subjectivity of actors with diverse cultures and rationalities, at large territorial and organizational scales.

Figure 3.2. System complexity and value plurality (Frame and O’Connor 2011)

In other words, monetary representation is only relevant when a service is contracted out, or when the conditions for producing the functionalities underlying it are negotiated. It is not relevant when expressing the non-market use values of these functionalities, as well as their non-use values.

Moreover, the PSS is indivisible from an even more complex system: the functional ecosystem within which it develops. A PSS offer can only be “solidly” and “pertinently” associated with a single monetary representation at the end of a constantly renewed negotiation, aimed at qualifying and enhancing its interactions with the functional ecosystem. And these negotiations can only be conducted by actors in the functional ecosystem. The condition of rigor associated with the uniqueness of the monetary representation of an offer is therefore twofold: it is due to the perpetual renewal and the socially detailed nature of this representation.

More generally, how can the solvency of entities contributing to a PSS be strengthened, i.e. at the level of a niche, when it is not strictly possible to associate a single universal political or market price for the functionalities produced there, i.e. a price applicable to the entire sociotechnical system? It is no longer only the relationship between the exchange value of standardized commodities and services – which can therefore be identified beyond the locality of their production – and the relationship between the plural values of use and non-use specific to that locality that must be addressed. A problem of embedding functional production niches and redistribution and public investment regimes and landscapes in local functional ecosystems must be considered.

The functional economy is driven by a deliberative process, formal or informal, from the co-design of an offer to the evaluation of the co-produced solution and the non-market and commercial valorization of its utilities.

It is through this deliberative approach that we will address the issue of monetarization within the open and dynamic framework of a sociotechnical system. The approach we suggest is quite simple: since the distinction between monetary and non-monetary representation of the value of a production is only consistent within the functional ecosystem, it must be extended to other actors.

Such an ambition does not only imply producing information that promotes the recognition of use and non-use values of locally produced functionalities. The ability of people in other production areas to recognize themselves is crucial.

If the people who decide in these other localities are indeed the agents considered by the neoclassical economy (determined by rationalities specific to their sociotechnical niche), then their ability to recognize an “exogenous” functionality is limited.

If, on the other hand, these people are also driven (and not only determined) by a process of seeking information beyond the systematic contributions of rigid channels, formalized, in particular, by accounting regulations, or by algorithms built on the basis of more or less homogeneous behavioral assumptions, then their propensity to recognize their interest in contributing to a multifunctional co-production is real.

The three issues in Gaudin (2001) with the mobilization of the category of actor – objectification of what is observed, articulation between individual and collective action, and choice of methodological paths – are thus indivisible from those of the solvency of an entity.

3.1.1.2. Beyond micro–macro abstraction: the territory

The concept of territory offers the possibility of a step sideways. It makes it possible to return to the figure of the actor and the dimensions of their inclusion in the sociotechnical space in which the analysis of a collective process of production, evaluation and valorization is carried out.

According to Colletis et al. (2005), “for there to be a territory, three proximities must be combined: spatial, organizational and institutional”. In our opinion, these proximities constitute a potential territory, which must be revealed through a coordination situation, ranging from the resolution of a problem encountered by an actor located in time and space to a territorial development project that converges the time horizons of actors anchored in this triple proximity.

Production is a situation of coordination, especially when we consider this production in a functional economy as we understand it. It is nourished by a collective work of solving a political, economic and social problem faced by a group of self-constituted actors in a functional ecosystem.

The collective situation of these actors in the sociotechnical space influences their ability to carry out this work: territorial proximities determine the overcoming of the barriers that prevent niche functional innovations from being recognized at the regime level and valued in other niches.

These actors are also collectively located in time. We will show that it is the dynamics of convergence of their time horizons – through deliberation – that determine the collective capacity for production, contractualization and valorization.

A territory does not exist forever. The way in which the potential of the territory – the proximities introduced by Colletis et al. (2005) – is materialized is closely linked to the possibility of the emergence of one mode of valorization rather than another.

Landel and Senil (2009) highlight three operations essential to the construction of the territory and consider it as a resource:

- – separation makes it possible to assign specific qualities to the territory;

- – projection makes it possible to use these specific qualities as markers of the representations that the actors make of the future of the territory, and to place these actors within a common horizon;

- – articulation makes it possible to associate different objects with these specific qualities, within a contract resulting from cooperation between actors of multiple origins and inscribing these actors in a shared temporality.

Thus, “the territory project would become a space for managing paradoxes, which can be declinable ad infinitum to local specificities. It would be an opportunity for new forms of public debate involving stakeholders in a new institutional game. State, local authorities, companies, associations, services express contradictory logics, based on different objects” (Landel and Senil 2009).

In our opinion, it is through these three types of operations that the combination of spatial, organizational and institutional proximities presented by Colletis et al. (2005) as necessary to “reveal” the potential of the territory is achieved.

- – Separating makes it possible to represent issues related to the territory as represented until now, and to question the relevance of established spatial, organizational and institutional proximities.

- – Projecting makes it possible to determine judgment criteria relating to the specific qualities of the new territory, and to build a scenario that places the actors in a shared horizon of representation and action, thus renewing institutional and organizational proximity.

- – Articulating makes it possible to weight objectives according to these criteria, within the framework of a contract that places the scenario in a shared temporality, which leads to the renewal of organizational proximity and reconfiguration of their anchoring in spatial proximity.

A functional ecosystem must be considered as a territory of the functional economy. And the construction of a PSS-type offer drives the construction of this functional territory, which in turn allows the founding innovations of this offer (which are niche innovations) to be anchored in the sociotechnical regime.

The separation of the qualities of the functional ecosystem is both the separation of the components of the performance of a production activity and the separation of the components of use, non-use and exchange of the value associated with it.

The projection is the collective design of the functional offer, which is both a performance scenario and a value recognition scenario.

The articulation embodies the functional ecosystem into a solution that is not only made up of products and services, but also of the materialization of the common institutional horizon resulting from the projection.

In other words, in a functional economy model, an institutional solution accompanies an organizational innovation and makes it possible to link the innovation niche to the regime that it makes favorable to the diffusion of this innovation.

Figure 3.3. Dimensions for evaluating the performance of urban innovations considered by the Eurbanlab approach (Bosch et al. 2013)

3.1.2. Toward a cooperative transaction society

3.1.2.1. Double contingency and valorization

Niklas Luhmann (1982, 1988, 1986, 1986, 1991, 1995) partially inspired his theory of social systems from Talcott Parsons’ teachings1 (1951, 1968) that social communication makes it possible to solve a situation of double contingency. This situation can be described as a state of uncertainty and indecisiveness resulting from the interaction between two actors, whose respective thoughts cannot be known to either of them, making the behavior of either contingent part of the other’s behavior.

For Luhmann, Communication is a very special process. In his view, care should be taken not to consider “that the information transmitted is the same for the sender and the receiver”, the identity of information being “thought to be compatible with the fact that its meaning may be very different for the sender and the receiver” (Luhmann 1991, p. 135).

The functional economy is driven by a Communication process aimed at bringing actors closer together by recognizing the ecological, social and economic utility of PSS offers that can be designed, produced and enhanced collectively.

On the one hand, “functional coding” is carried out by the senders of information relating to the functional qualities of a production and the conditions necessary for a sustainable perpetuation. On the other hand, “service-based coding” is carried out by the senders of information related to the uses of this production and the sociopolitical and market conditions for its recovery.

This Communication reduces a situation of multiple contingency by including actors in a renewed functional ecosystem.

According to Parsons (1951, 1968), the solution to the state of dual contingency results from a consensus between actors obtained through interaction between culturally inherited value systems. This cultural heritage can be understood in terms of the relationship between time, information, Communication, and organization.

We have argued above that valorization produces the institution as much as it does the other way around. This is what we will illustrate now. The valorization operation, because it is based on information and produces other information, cannot be dissociated from a Communication operation, which implies in particular considering the transactional act from the angle of the cultural heritage mentioned by Parsons.

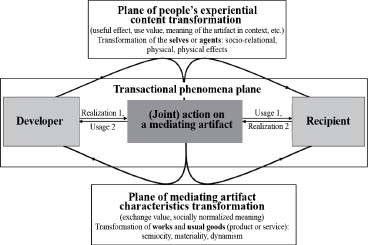

Borrowing the concept of transaction from Dewey and Bentley (1949), Zacklad (2006) identifies four steps: “Virtualization (the potential recipient expresses the vision of a project to which the developer subscribes or vice versa), the acquisition of skills (the developer or co-developer acquire the skills necessary to carry out the project), performance (more or less simultaneous transformation of the mediating artifact and the people carrying out the content of the project), approval (symbolic or tangible reward of the director by the recipient).”2

Zacklad (2007) then develops the concept of cooperative transactions, characterizing productive interactions associated with meetings that allow the joint transformation of a mediating artifact (artifact or medium) and stakeholders.

Figure 3.4. Diagram of the components of cooperative transactions (adapted from Zacklad 2007)

These cooperative transactions generate new experiential content, described in terms of transformation “physical – mainly bodily effects (mainly sensory experience); expressive – mainly psychic effects (mainly representational experience); agentive – mainly socio-relational effects (mainly relational experience)” (Zacklad 2008).

The concept of a cooperative transaction can be compared to Communication in the sense of Luhmann. Communication must indeed be treated “as a unit with three positions”, which are “the synthesis of three elements – information, communication and the expectation of success –…” (Luhmann 1991, p. 136). However, two people engaged together in a cooperative transaction are each waiting for success – which is achieved when the combined assessment of the satisfactory nature of the coaction on the mediating artifact is made.

For Luhmann, “the synthesis of the three elements – information, communication (Mitteilung) and the expectation of success – in the same act of attention presupposes ‘coding’” (Luhmann 1991, p. 137). From the point of view of the cooperative transaction, this coding is carried out in the experiential content of the people who exist before the transaction and allows both the recognition of the mediating artifact – for example a PSS offer – and that of the associated values.

Communication – in its broadest sense (“Kommunikation”) – is to be seen as a “selection process” in which “the selection that is updated in the communication constitutes its own horizon. It already constitutes what it chooses as a selection, i.e. as information” (Luhmann 1991, p. 135). To continue the rapprochement, the selection made by each person in the experiential content they mobilize to qualify the mediating artifact is already the horizon of the transaction.

In other words, the producer and the beneficiary of a functionality each select from their own representation system – in their experiential content – information describing the conditions under which this functionality is made available and the service it provides. This selection is the horizon of the transaction: the combination of the information selected by the two participants cannot describe anything other than what they perceive about the production methods and the advantages of the service.

Thus, the richer the experiential content, the broader the range of functions recognized in a production can be, and the better the non-use, use and exchange values associated with these functions can be integrated into the transaction.

3.1.2.2. Deliberate to establish agreements

The cooperative transaction changes both the plural value systems mobilized by the actors, and their individual representations of the objects they consider together. In other words, people’s experiential content and mediating artifacts are co-evolving during this transaction.

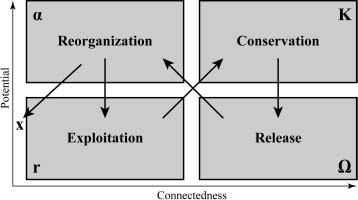

The four phases of a cooperative transaction, described above – virtualization, skills acquisition, performance, sanction – can be compared to those of the Holling adaptive cycle mentioned in Chapter 1 (see section 1.2.2.2).

Figure 3.5. Two-dimensional representation of the four phases of an adaptive cycle (Holling 1995)

Returning to the register of the functional economy, considering that the co-implementation of a PSS is the result of a concerted specialization between actors, which emerges from a cooperative transaction, this rapprochement could be illustrated as follows:

- – Virtualization, during a cooperative transaction within a functional ecosystem, corresponds to the meeting of the expression of utility needs and production capacities. In our opinion, this step results in an Ω phase called the “release” of resources (here informational).

- – The acquisition of skills, during a cooperative transaction within a functional ecosystem, corresponds to the operationalization of concerted specialization. In our opinion, this stage involves an α phase of “reorganization-renewal” of functional production capacities.

- – Performance, in a cooperative transaction within a functional ecosystem, corresponds to the co-production of functionalities. In our opinion, this stage involves an r phase (known as the “growth/exploitation” phase) of the utilities available and valued socially or in the context of market services.

- – The approval of the cooperative transaction corresponds to the material or symbolic reward for performance, i.e. a collective and differentiated response to the expectations relating to multifunctional production. This step results in a K phase, the “conservation” of experiential content and mediating artifacts, during which the message of performance is decoded, before being interpreted in the Ω phase of the next cycle.

Once the reward has been paid, it frees up information resources. It opens the door to the mobilization of performance lessons and constructive criticism of previous contractual arrangements, and thus to another separation of the economic territory that is the functional ecosystem, through the renewed expression of its qualities, for future projections and articulations.

Returning thus to the territorial construction operations proposed by Landel and Senil (2005), the Ω phase, or virtualization phase, refers to the separation operation proposed by Landel and Senil (2005); the α phase, or skills acquisition phase, refers to the projection operation; the r phase, or performance phase, refers to the articulation operation, while the K phase, or approval phase, describes the loop between the articulation and a new separation.

In other words, it is a question for the actors to mobilize the renewed qualities of the territory in order to produce not only collective representations, but also collective capacities, through the individual and differentiated acquisition of skills. Then, combining the implementation of these skills within a common horizon makes it possible to envisage this horizon in terms of a renewed and shared representation of the productive territory. The reward in act, material or symbolic, then temporarily structures the territory that has become a territory of plural performances defined contractually for the time of evaluation and valorization.

Through these operations, the cooperative transaction proceeds from the reduction of a multiple contingency situation and accompanies the materialization of the territory potential contained in the spatial, institutional and organizational proximities introduced by Colletis et al. (2005).

In short, the cooperative transaction produces the territory of the functional economy that is the functional ecosystem, as much as it feeds on it.

If this transaction could lead to a reduction in the level of contingency during the Communication process between actors during the co-production of PSS offers, it would act as an organizational closure within the functional ecosystem.

The challenge is to encompass the three positions of the Luhmannian Communication within the same transactional act: information (qualification of the functionality and conditions of the sustainability of its production), communication (act of social and/or commercial contractualization) as well as the expectation of success in terms of non-use, use and exchange values (via the valorization institutions).

We find here the three situations of what we described in Chapter 2 as a dissipative cycle of territorial economic information (see section 2.2.1.2). Information relating to an activity, the economic component of which is only partially monetarized, must not be dissipated by the contractual act and the accounting valorization.

The cooperative transaction logic applied to functional economics leads to presenting valorization as a means of the institution, instead of legitimizing valorization only when it takes place within an already established framework. The two logics are co-existing. While it is necessary to have a wealth representation grid to value, the construction of this grid is the result of past valorization processes that have created the need and legitimacy of a new grid. A frame is always in motion.

3.2. To discuss is to produce

Friedberg (1993, p. 13) considers organization – or rather the phenomenon of organization – as “the contingent and always temporary result of the construction of a local order whose relatively autonomous characteristics structure the capacity for collective action of the persons concerned. It is at the same time container and content, structure and process, constraint for human action as well as its result. It is what gives collective enterprises their duration and thickness. Its existence has profound implications for both reflection and action”.

This way of presenting the organizational phenomenon could correspond to what we mean by “territorial information system”: a phenomenon, container and content, structure and process, constraint for human action and its result.

One human action that we consider in particular is the one that drives the co-construction of product-service offers in the functional economy: this action is part of a cooperative transaction through which the local and provisional order of production and valorization is constituted: the functional ecosystem.

To return to the distinction of the components of work proposed at the end of Chapter 1, if the cooperative transaction is the result of economic work, it is only the emergence of a more fundamental phenomenon that results from social work: Communication in the sense of Luhmann. And it is to join the fields of representation of the social and economic components of plural work that we have assimilated this cooperative transaction to a Communication, from which we have distinguished three positions: information, contractualization and valorization.

The terms that describe these three positions are to be understood in a particular sense.

In our opinion, information refers to the expression of the needs for utilities and functional production capacities necessary to make these utilities available. It is not only a set of data conveyed by the communication – the “Mitteilung”, which is only one of the positions of Luhmann’s “Kommunikation” and which we will more commonly call “content”. This information is also intrinsically an information process. It continuously produces the evaluation criteria against which representations of production methods and values associated with production will be organized.

Contractualization refers to the strictly economic part of the cooperative transaction. It is the passage that follows the social expression of a need and formulates its content through generic performance criteria and specific indicators, but which just precedes the structuring of the physical and digital response modalities to which industrial work will be employed.

Valorization does not only refer to the interpretation of performance in terms of non-use, use and exchange values. In our opinion, it describes the joint transformation of people’s experiential content and the representation and information systems that they integrate and institutionalize.

We have indeed argued that valorization produces institutionalization as well as the other way around. And this is particularly important if we return to the issue mentioned at the beginning of the chapter, which can be reformulated as follows: how to enhance the value of locally produced functionalities for actors who do not have the references to enable them to recognize the repertoire of utilities conferred by these functionalities?

We then discussed an expansion of the functional ecosystem. More precisely, it is a networking – by a territorial information system – of several functional ecosystems, each driven by cooperative transactions with particular Communication processes, specific to their productive localities.

The networking of functional ecosystems through a territorial information system is of particular importance when decoupling ambitions impose a common horizon built collectively and therefore the coordination of spatial, organizational and institutional proximities. The aim is to connect actors who do not share transactional experience and to integrate them into a concerted specialization, no longer only within but also between functional ecosystems. The objective is to ensure a joint but differentiated – and absolute – improvement in the registration of their activities in the territory they share.

One of the most central economic issues, at a time when the numerical dimension of industrial work (structured by economic work) tends to take precedence over the informative dimension of social work (structuring for economic work). In other words, at a time when the disruptive charge – sometimes even described as predatory – carried out by North American platforms, is the question of the relative places of information, knowledge and shared knowledge heritage in the relationship between humans and information networks.

3.2.1. Toward a hermeneutical and contributory web

3.2.1.1. Dialogue about functionality

Islets of rationality, metaphorically described by Fourez (1994, p. 57) as “knowledge emerging in an ocean of ignorance”, can be identified within the territorial space of representations. The existence of these islets promotes local understanding between actors, and therefore their cooperation, and thus the co-evolution of innovations between different economic scales. Their emergence involves conciliation and arbitration between different points of view around a project (Fourez 1997, p. 131).

In the case at hand – the networking of functional ecosystems – it is not so much a question of considering the emergence of knowledge in an ocean of ignorance as of apprehending the coexistence of various rationalities in a territory under construction.

In order to have a clearer vision of this territory, controversy maps (Latour 2001) can be drawn up. Their objective is to clarify the contours of certain issues considered socially lively (Alpe 1999) – both in society, in reference knowledge and in school (or even university) knowledge (Legardez and Simoneaux 2011).

For Latour (2001), controversies must lead to “the construction of a cartography of subjects which are the subject of an in-depth expertise and which, at the same time, have become cases, often confused, mixing legal, moral, economic and social issues to the point that ‘these public things’ are becoming more and more the heart of political life.”

Those that generate debates between specialists in different disciplines, professional experts and local players, are part of the economic innovation process. The state of controversies determines, in particular, the conditions under which different actors meet, at the confluence between the major trends in society, the emergence of innovations and their appropriation.

Venturi (2008) notes that “the purpose of controversy mapping is to contribute to the development of these mechanisms [of representation, negotiation and consultation] through the creative use of digital technologies.”

The linking of several functional ecosystems, i.e. several economic territories, recognizing a common horizon, can be based on a model of dialogue based on knowledge. This type of model is part of a perspective of understanding complexity through reciprocal communication and developing people’s learning capacities (O’Connor 1999).

More specifically, we will focus on a hermeneutic web-based platform, the ePLANETe.Blue web portal, which is a participatory and contributory model dedicated to collective choice. This portal offers a heuristic navigation motivated by cross-links through an organization by thematic gates, spaces, galleries and object profiles, which allows us to engage protagonists in a process of social, economic and ecological improvement.

Figure 3.6. Simplified representation of the galleries of the dialogue portal around ePLANETe.Blue knowledge. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/morlat/sustainable.zip

The central approach proposed by the ePLANETe.Blue portal is based on the KerBabelTM Deliberation Matrix (KDM). By browsing this gallery, contributors can change the representation of a system (e.g. a PSS) and support the construction of its social meaning (e.g. the expression of value judgments in a functional ecosystem).

After analyzing the field and formulating objectives following an in-depth study (interviews, literature review, etc.), contributors are invited to identify a complex problem of “social choice” characteristic of this system. The problem may be, for example, to structure the different components of the value they associate with a PSS in order to co-construct its financing by taking into account the logic of the public, market and popular economy – without opposing them.

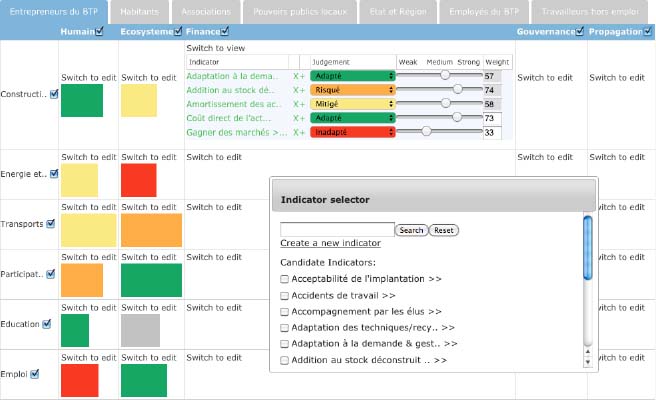

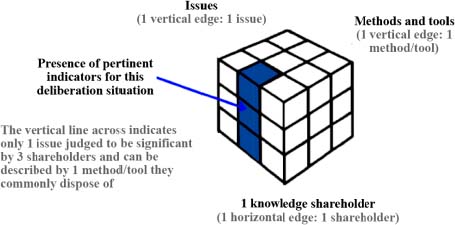

The KDM, based on the idea of the Rubik’s Cube(TM), structures this social choice problem in terms of stakeholders, categories of issues and action scenarios. The representation (Figure 3.7) could, for example, be adapted for deliberation among stakeholders on how different PSS scenarios can be compared according to their responses to different territorial issues.

Figure 3.7. Three-axis structure of the KerBabelTM Deliberation Matrix (Douguet et al. 2018)

A cell (shown in color, Figure 3.7) shows the crossing between the three selected axes. Each person or group represented within the “actors” axis is invited to make a value judgment regarding the way in which, from their point of view, each of the scenarios responds to each of the issues. Judgments are visualized by a color associated with a “meta-category”: for example, green for “Adapted”; red for “Unadapted”; orange for “Risk”; yellow for “Mitigated”; grey for “Not concerned”3.

Colors (Figure 3.7) correspond either to a direct judgment concerning each cell, or to the synthesis of several “baskets” constituted, for each cell, with one to five indicators for aid to deliberation and aiming to specify the judgment expressed.

Representation (Figure 3.8) indicates that a group of construction contractors used indicators to clarify their judgment regarding the adequacy of a territorial scenario of financial support for the renewal of uses in construction.

Figure 3.8. Example of use (screenshot) of the KerBabelTM Deliberation Matrix. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/morlat/sustainable.zip

The contributor also has the possibility of associating a discussion forum with each indicator he/she mobilizes. This is done, for example, to justify the choice of a color, or to discuss the subjective weight assigned to the indicator in order to weight the importance of the argument made by this indicator in the overall judgment concerning the issue-scenario crossing concerned.

3.2.1.2. From information to waiting for success

The deliberation support indicators can be kept in a complementary gallery, the KerBabel™ Indicator Kiosk (KIK), which is a catalogue of the indicators used by each user community. The indicators are described by meta-information: name, acronym, short description, scientific profile, method of interpretation, sources of production (including knowledge mobilized), status, robustness, etc.

An indicator is not only a decision-making aid, or an argument for the punctual expression of a value judgment. For O’Connor (2004), the use of indicators establishes a dialogue through which knowledge producers and users jointly assess the relevance of knowledge mobilization in governance situations of complex problems.

However, a dialogue, like any communication, implies coding. Let us imagine two actors meeting to discuss the utilities and conditions of acceptability of a scenario. The indicators used by each of them will be very different. Let us take again the example of the previous point. A resident invited to express an opinion on the effect of the territorial scenario of financial support on his own relationship to construction issues will not always use the same indicators as those used by the construction contractor. And when this is the case, considering for example the Kwh/m2 indicator, the construction contractor and the inhabitant will not have the same interpretations.

This is not a question of divergence of points of view, but of views that intersect around the same analytical reference point – the indicator – without associating it with the same object or even pursuing the same analytical approach. For example, the construction contractor will think of Kwh/m2 in terms of the constructive standards to be respected, while the inhabitant will observe this indicator in an energy expenditure approach.

The construction contractor and the inhabitant can each claim to be favorable or not to the scenario considered and specify their judgment by the Kwh/m2 indicator; they do not speak about the same thing and therefore cannot communicate. The deliberation then reflects a situation of double contingency within the meaning of Parsons (see section 3.1.2.1).

This is why keeping meta-information associated with indicators within an inventory is crucial. In addition to documenting the indicators, it is necessary to identify the metadata associated with their use, i.e. any form of knowledge related to these indicators, in order to ensure an acceptable degree of visibility and transparency regarding this knowledge.

The KIK gallery fulfills this function. It allows us to navigate between indicators using thematic filters, proposes to establish links between these indicators and methods and tools, fields or approaches that mobilize them, and offers access to relevant information (documents and websites).

To reduce the contingency situation that characterizes a deliberation situation, it may be useful to select indicators that “speak” to as many contributors as possible. A deliberation during which the expression of the point of view of certain contributors would be favored by the overrepresentation of certain indicators systematically associated with the same analytical methods would be biased.

While listing indicators is important, it is equally important to allow contributors to select indicators that will ensure the representativeness of points of view.

The KerBabel™ Representation Rack (KRR), a complementary gallery to KDM and KIK, proposes a process for identifying and collecting indicators for this purpose.

Each deliberation situation is particular, unique, because of the problem addressed, the specificities of the set of actors, methods and tools used by each one to describe the impact of a scenario on the effects of its activity, and on the response to shared challenges.

The KRR makes it possible to situate the indicators resulting from a deliberation in relation to the forms of knowledge available.

Designed along four axes, it allows each indicator to be resituated according to:

- 1) the categories of actors likely to mobilize it (scientists, experts, companies, inhabitants, public authorities, etc.) – referred to here as “knowledge carriers”;

- 2) the theories, conceptual approaches (scientific, vernacular or other), methods and tools (for analysis, modeling, etc.) and various practices by which these actors are likely to mobilize it;

- 3) the scenarios or objects for which it can be used for comparison;

- 4) the issues it addresses.

For Douguet et al. (2018), the first two axes, which provide access to an understanding of the sources of indicators, provide an overview of the Knowledge Offer. The other two structure a need for contextualization of knowledge, thus describing a kind of Request for Knowledge (ibid.).

By repositioning the indicators mobilized, the KRR makes it possible to assess the relevance of the available knowledge, according to the four selected axes (van der Sluijs et al. 2008; Douguet et al. 2009; Funtowicz and Ravetz 1994).

The knowledge carriers – who are the actors under deliberation, but also any other interested actor – evaluate the adequacy of each of the indicators produced under deliberation for each “crossover” between the four axes (actors, scenarios, issues, tools). Each contributor will have to choose between “0”, which means “not relevant,” “1” – “low relevance”; “4” – “high relevance” (default value).

The illustration (Figure 3.9) describes the principle of what Douguet et al. (2015) call “KnoT” or “Knowledge Tesseract” to illustrate how the relevance of the indicators can be described at the intersection of the four axes mobilized by KRG. Its representation in two dimensions implies to freeze one or the other of the four axes.

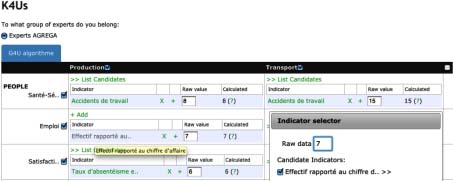

The KRR is not only dedicated to the production and selection of indicators for deliberation. It can also be used to select indicators for normative evaluations. Another gallery, from the ePLANETe.Blue portal, KerBabel™ for You (K4U), offers a method for co-producing algorithms to evaluate the performance of a system according to several criteria, each of which will be specified by subsidiary objectives.

Figure 3.9. “KnoT” for one scenario, three issues, three shareholders and three tools (Morlat and Douguet 2018)

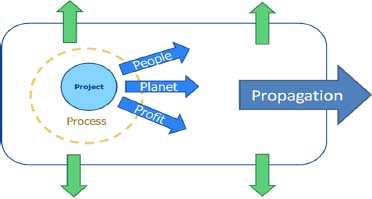

Indicators produced during a deliberation can be selected through KRR and used to assess the influences of different scenarios on system performance, according to a number of predetermined criteria. The choice of performance criteria considered by Bosch et al. (2013) – social, ecological, economic, governance and the propagation of solutions – can be used, for example, to assess the sustainability performance of a system (see section 3.1.1.1).

The indicators are no longer deliberative indicators but performance indicators that contributors associate with subsidiary objectives related to each performance criterion. The set feeds a simple algorithmic formula that makes it possible to compare the influences of the scenarios to the achievement of the performances considered according to each of the criteria.

The functioning of K4U implies that users, this time in the role of evaluators, assign a score of 0–10 to each indicator by following previously and collectively developed rules of interpretation and standardization4.

After assigning a score to each of the indicators, the K4U algorithm associates a score to each performance axis, in order to generate a profile with n performance dimensions – as many as the criteria (five if we consider the social, ecological, economic, process, and propagation criteria). By default, the algorithm performs the weighted average of the scores assigned to the indicators associated with the criterion in question.

Each of the galleries presented above can be used in a specific and independent way. However, it is their discursive use, by navigating from one to another, which strengthens the situation of knowledge and promotes a multi-stakeholder dialogue. To do this, we could associate some of the galleries of the ePLANETe.Blue portal with the three positions of the Communication described by Luhmann. The deliberation matrix could be considered as the place where complex information is collectively composed (based on the indicators proposed by each contributor for all the others), the representation rack as well as the choice of communication construction modalities, while the choice of objectives, indicators and weights when formulating the multi-criteria evaluation algorithm could be motivated by the expectation of a shared success.

Figure 3.10. Construction of a multi-criteria evaluation algorithm of the “K4U” type on the ePLANETe.Blue portal

3.2.2. A contributory platform for political economy

3.2.2.1. Reproduction through communication

The collective journey through the galleries of the ePLANETe.Blue portal catalyzes the mediation of knowledge and foreshadows the potential emergence of new strategies and decision-making approaches, compatible with territorial innovations.

During this process, the dialogue between stakeholders leads to changes in the choice of indicators (and therefore knowledge) mobilized. Comparison between several scenarios according to different performance criteria (via the K4U algorithm) can lead to an evolution in the choice of indicators used to support a value judgment (via the deliberation matrix). Changing the way they provide information about the values they attribute to the system described will lead actors to reconsider the links between indicators and evaluation methods (via the representation rack) as well as the rules for interpreting indicators (via the KIK).

This dialogue between producers and users of indicators – who may be the same people but who assume different roles (stakeholders, knowledge carriers, producers of performance objectives or evaluation standards) – generates a territorial heritage, as defined by Colletis and Pecqueur (2004). The formation of this heritage through the use of ePLANETe.Blue can be illustrated through an adaptive cycle detailing the phases of a cooperative transaction, following the approach proposed above, and comparing them both with the operations by which Landel and Senil (2005) describe territorial construction (see section 3.1.2.2).

The KDM is a privileged place for virtualization (cooperative transaction approach), which we have compared to an Ω phase called “release” of information resources (adaptive cycle approach) as well as the separation operation of Landel and Senil (2005). It is indeed the nature of a deliberation to re-examine what they call the specific qualities of a territory by expressing value judgments based on arguments themselves based on indicators.

The KRR is the place where skills are acquired (cooperative transaction approach), a collective acquisition resulting in a shared representation of the knowledge available for deliberation or evaluation. It corresponds to an α phase called “reorganization-renewal” phase (adaptive cycle approach) of the qualities of the territory subject to this deliberation and/or evaluation, during the process of repositioning the available knowledge. The process of establishing the relevance of this knowledge to the system under consideration is thus part of Landel and Senil’s (2005) projection exercise. The aim here is to mobilize the qualities of the territory, renewed through deliberation, to produce collective capacities to deliberate and evaluate on the basis of a body of knowledge restructured by putting the indicators in a situation and then selecting them.

The multi-criteria evaluation algorithm K4U refers to the collective performance (cooperative transaction approach) by which contributors compose the objectives that constitute the algorithm and associate indicators with these objectives. This step corresponds to an r phase known as the “growth/exploitation” phase (adaptive cycle approach) of the capacities to anchor the individual representation of performance in a shared convention. We bring it closer to the articulation described by Landel and Senil (2005). It is indeed a combination of the implementation of the skills acquired over a common time horizon, that is the evaluation of the performance of the system under study.

The KIK is, in our opinion, the place where the approval is imposed (cooperative transaction approach). It is through it, and more precisely through the redesign of the rules of evaluation, interpretation and other meta-information related to the indicators it houses, that the material or symbolic reward for performance is made. This stage is reflected in a K phase, known as “conservation” (adaptive cycle approach), during which the meta-information associated with the indicators freezes, the time of – or rather in – the compensation, before they are again mobilized by other deliberations, representations and evaluations. It is indeed a loop between the articulation and projection operations described by Landel and Senil, between one situation of dialogue and another.

This notion of closure, in response to a cognitiveist approach, inspired by5 Santiago’s Theory (Maturana and Varela 1994) and extended to the social sphere, could invite us to consider the territory as the result of a relationship between the individual production of representations and shared representations, i.e. territorial heritage. One of the founding concepts of Santiago’s theory is autopoiesis, a phenomenon by which a system subjected to external disturbances perpetually generates and specifies its own organization6. One could then consider that participation in a deliberation renews the actor’s system of representation from within, i.e. renews his/her psychological system.

However, the extension of the concept of autopoiesis to the social domain has been the subject of much debate (Fleischaker 1992; Mingers 1995, pp. 119 et seq.). Maturana and Varela in particular, the founders of this concept, do not strictly speaking envisage a social autopoiesis. For Maturana (1988), language allows individuals who are part of the social system to carry out their biological autopoiesis, without the system being autopoietic in itself. And for Varela (1981), if the social system can be characterized by a process of organizational closure that approaches autopoiesis, the concept of production network that characterizes this concept must be limited to the physical domain.

Among the authors who, on the other hand, accepted the idea of a social autopoiesis is Niklas Luhmann. His theory of social systems – widely discussed in the first part of this chapter – is even based on this concept, and strictly circumscribes its application to the social domain.

The systems considered by Luhmann are the psychological (individual) and social (group) systems. These systems are not only in dialogue, but also in interpenetration, that is, in a general relationship in which “each system puts its own complexity at the service of another system” (Martuccelli 1999, p. 154). For Luhmann, this relationship reflects “the way in which an autopoietic system presupposes the achievements of a system’s autopoiesis and can thus treat them as part of its own system” (ibid.).

In short, Luhmann (1990) considers that “social systems use communication as their specific mode of autopoietic reproduction. Their elements are communications that are (…) produced and reproduced by a network and that can only exist within such a network.

Based on this idea, returning to the functional economy – and more generally to political economy – we argue that economic information can only exist within a network of actors who can communicate.

It is through a communication situation that actors produce indicators of use values, foresee levels of exchange values while expressing the judgments of non-use values that form the basis of sustainability criteria. This situation implies that each actor in the territory considers the other actors as part of its own system of activity, and that all these actors are together able to situate the knowledge mobilized for the determination and interpretation of these different indicators, levels and criteria.

3.2.2.2. Contributory institutionalism

Economic evaluation with a view to sustainable development faces the same type of limitations as those considered by Hill (1997) while observing the traditional model of public policy development and implementation. Most public administrations are dedicated to a particular function (e.g. mobility, housing, and health) and not to the response to a problem (e.g. fuel poverty). This organizational system reduces communication between actors and thus collective capacity, both in terms of formalizing the problem, choosing the actions to be undertaken, investment and evaluation.

In the market sector, economic valuation is confronted with another limitation, that of – and despite digital ecosystems – a mainly sectoral approach, based on the value chains of the industrial era. A juxtaposition of independent views carried by market actors on the utilities of sectoral productions reduces the space of evaluation to a framework of exchange relations, and its temporality to that of the relationship to access to financial capital.

In either field, public or private, the evaluation method is dictated, imposed, by the conformation of the current relationships between actors, and by the influence of this conformation on the representations of the space and time of productions and valorizations. On the contrary, it could be considered intrinsically at the scale of a territory, in a collective projection approach specific to the problem addressed.

The anchoring of the evaluation system should in short be a broadening of the institutionalist conception of the economy (Commons 1934; Polanyi 1957).

For Vivien (2009), in such an approach, the multiplicity of stakeholder profiles and territorial relations implies a multiplicity of evaluation and deliberation processes on the criteria for value formation. But this relative complexity makes it possible to arrive at a specific methodological response based on tools that can encompass all territorial spaces and temporalities.

This is precisely what the ePLANETe.Blue portal allows. Support actors attached to different institutions and not using the same evaluation tools, in the construction of a collective representation of the interweaving of various territorial functions and a shared method of evaluating a social choice problem.

The work of contribution on a dialogue portal around knowledge such as ePLANETe.Blue is more broadly a re-articulation between psychological and collective individuations in the sense of Stiegler (2006), and, on the other hand, a technique – a technique referring here to evaluation in that it constitutes a concrete and effective environment linking the actors, in their individuality, to the territory, i.e. the transindividual that is for Stiegler what produces social matters (see section 1.2.2.2).

Economy is a social institution. And as a technique that produces its environment within this institution, evaluation – by its political, social, industrial and market dimensions – is the expression of a transindividual which, in our opinion, would benefit from constant renewal. In addition to the performative purpose of evaluation in the context of a particular transaction, it is indeed the renewal of people’s experiential content – to use Zacklad’s expression (see section 3.1.2.1) – as well as the inclusion of a group in a synchronism of the relationship to wealth, which must be considered.

The territorial assessment process as it can be conceived at a mesoeconomic level and over a fairly long period of time, that of institutions and policies, is therefore inseparable from the assessments that drive diachronic negotiations conducted at different time and territory scales by different groups in relation to the value of various productive phenomena.

Such negotiations cannot be conducted in a territory that is unable to put into practice the knowledge mobilized by both sides. Leaving the sectoral representation of the industrial economy and the disruption led by the digital platforms of the ultra-liberal economy known as the knowledge economy, or cognitive capitalism, to fix the synchronism of the relationship to wealth would have this effect. GAFAM platforms in particular, known as collaborative platforms, often have the related effect of standardizing economic representations and behaviors. In this respect, they do not contribute in the sense of participation in the production of not only knowledge, but also territorially anchored and shared knowledge heritage.

More generally, deterritorializing and overly standardizing the format and content of economic representations deprives actors of their sovereignty in the exercise of local negotiations around the value of productive phenomena, which tends to undermine participation in the democratic process.

However, if the territorial heritage – in the sense of Colletis and Pecqueur (2004), i.e. in reference to trust between actors resulting from successful cooperation experiences in the past – constitutes in this context a key element of the potentiality of a collective capacity for action; it must be assumed that it can be dispelled.

And if this heritage can be dissipated, it must be assumed that the potential for cooperation may tend to disappear in favor of the exercise of a power: that of a representation, a method, to the detriment not only of other representations and methods, but also of the dynamics of the actors who carry them. This would lead to an impoverishment of the territorial heritage, a reduction in the potential for cooperation and socioeconomic innovations compatible with sustainable development.

Group work conducted on a contributing portal, and more broadly any deliberation process between actors in a territory, therefore has an intrinsic economic value.

3.3. Conclusion

The first three chapters made it possible to raise an economic issue. Solvency, i.e. the ability of an entity to meet its financial commitments, is generally considered through the relationship between the economic and industrial components – physical and digital – of the broad conception we have of work. What we have just illustrated in this chapter is that, in a perspective of sustainable development, financial work must be captured by the history of territories, and redefined in terms of what the actors who build them expect from them, that is, in a circumscribed vision of the future of ecological, social and economic systems.

As a new relationship to capital formation and exchange in their various forms, financial work can lead to supporting the sustainability of these systems to postponing the achievement of their critical thresholds over time. The horizon of wealth therefore now includes the creation of communities representing an ecological, social and economic debt, but also an industrial debt – physical and digital – so as not to exclude technological progress from the prospects for sustainable innovations.

This global debt must be balanced by local, contextualized and negotiated revaluation, and industrial and digital production offers this approach an interesting interface in which it impacts the “tripod” of sustainability while feeding financial profit.

The following three chapters propose certain principles and tools, all of which together constitute an approach whose first steps were the subject of our doctoral thesis entitled Dynamic Modeling of Cost Systems for a Sustainable Management of Territories (2016). It is an economic evaluation approach based on the recognition of evaluation as productive work, and therefore a self-referential approach that can be approached as an encoding, and therefore, intrinsically, as Luhmann’s Communication.

The territorial heritage of technical-economic and socioeconomic relations, which the concept of a functional ecosystem makes it possible to circumstantiate – not to circumscribe – in order to represent an analytical unit, is both a guarantee of the maintenance of the qualities of the representations that underpin the representation of utilities in a proven way, and a tool for the ecological, social, economic, industrial and financial valorization of these utilities.

It constitutes the shared resource, the territorial common good, from which entities draw a relational capacity with a capital value, just as it allows these same entities to recognize in these relationships a capacity with an asset value.

It is in this sense that we introduce a first principle, which states that the share of the overall operating cost allocated to a local production process – particularly industrial – must not be determined on the basis of the costs of the activities that contribute directly to it. The operating cost of a production process must be determined by how each entity or system that works in it contributes directly or indirectly to the achievement of a set of objectives that constitute the purpose of the process – a socially, politically-determined horizon of wealth.

It is only at the end of the construction of this horizon and the negotiated representation of each entity’s contribution to the progress that leads to it, that an allocation of the costs of building the society project can be made. And it is only in the knowledge of this allocation that the cost of the production process in question must be determined.

It is, no more, no less, a management control, carried out in a participatory and negotiated way at the territorial level, and aimed at revealing functional productions that remain invisible within the framework of the current territorial information system.

- 1 Luhmann attended Parsons’ courses at Harvard in 1961.

- 2 Zacklad is based on semiotics (Greimas 1966) used in the field of organizational communication by Coreen (1999).

- 3 The descriptive texts of the judgments (favorable, unfavorable, etc.) and the associated colors can be freely modified by the user during the construction of the matrix.

- 4 These rules are part of the meta-information documented in the KIK. In particular, they make it possible to make comparable the assessments of indicators relating to different evaluations, quantitative or qualitative, by reducing them to an evaluation on a scale from 0 to 10 using Likert tables composed on ePLANETe.Blue.

- 5 In this theory, biologists Maturana and Varela (1994) argue that “the cognitive act is not simply a mirror of an external objective reality, but rather an active process, rooted in our biological structure, by which we truly create our world of experience.” They also suggest that “when a living system interacts with its environment, it is not environmental disturbances that determine what happens in the living being, such as an external force acting on it (linear causality), but rather from within that system transforms its own structure in response to the disruptive agent (adaptation).”

- 6 An autopoietic system is “organized as a network of production processes of components that (a) continuously regenerate by their transformations and interactions the network that produced them, and (b) constitute the system as a concrete unit in the space where it exists, specifying the topological domain where it is realized as a network. It follows that an autopoietic machine continuously generates and specifies its own organization. It carries out this incessant process of replacing its components, because it is continuously subjected to external disturbances, and constantly forced to compensate for these disturbances. Thus, an autopoietic machine is a system of stable relationships whose fundamental invariant is its own organization (the network of relationships that defines it)” (Varela 1989).