5

Contractualizing: The Value in Act

5.1. Restructuring the transactional space

The co-production of product–service systems (PSS) de facto generates multi-stakeholder transaction situations, and therefore communication spaces, and in valorization spaces, intermediates between the micro and meso levels. Structuring these spaces within the territorial functional ecosystem could be an opportunity to reduce the dissipation of information inherent in any monetarization.

A service provided under contract during a transaction involving various performance objectives and whose levels are negotiated following the expression of multiple value judgments is associated with a price in euros. This price, which could be associated with an exchange value within the strict framework of the market transaction, does not exist on its own within the functional ecosystem. It is associated with a non-monetary representation of the use value assigned to the functionalities to which the market service is one of the access channels. These functionalities are themselves associated with monetary amounts corresponding to the maintenance costs of the productive phenomena that allow them to emerge, i.e. another exchange value.

In other words, a monetary indicator is associated with several monetarization singularities, i.e. several points where the multiple dimensions of space and time of value representation meet. These singularities can be linked to the same multifunctional production, whose governance is formalized by the PSS, within a functional ecosystem ensuring the function of a cooperative transaction and which can therefore be associated with a monetarization locality. Within this locality, the monetarization of the link between several monetarization singularities, aimed at decontextualizing the monetary representation of the value of the utility of the service – considered as a commodity – constitutes a financialization singularity.

What we mean here by singularity of financial valorization – or financialization – does not therefore correspond to a situation of monetary representation – monetarization – anchored in the territory where the PSS is built. In our opinion, monetarization is particular in that it is always part of the communication system that gave rise to the first recognition of the productive phenomenon to which it refers. Conversely, monetization relocates the monetary representation of the utility of this phenomenon.

What we mean by singularity of financial valorization is indeed a point of monetization – not monetarization. This singularity gives rise to a couple [price in € – documented utility] detached from the territorial communication as the source of the utility documentation, and put into circulation in another Communication, the financial market, whose connections with the first – i.e. with the territorial communication – are not traceable.

For example, in a broader representation horizon than that of a market service between actors in a territory, the financial representation of the expectations of the contractualized service is disconnected from the space of negotiated composition of value: that of the processes of the functional ecosystem that underlie the existence of functions whose actors in this ecosystem recognize functionalities that they associate with the utilities that form the service contract.

We therefore distinguish here between a territorialized market economy and financial markets: the economy of localities of monetarization embodied by PSS anchored in the functional ecosystem, and the economy of financialization singularities embodied by globalized systems for standardizing representations of the value of utilities.

A question then arises: does national accounting, as it is currently institutionalized, make it possible to make the link between localities of monetarization and singularities of financialization?

Let us consider this question by considering the formation of GDP – which is nothing more than a communication between niches and the sociotechnical landscape of Geels (2002). Is it the result of an aggregative passage giving rise to a macroscopic indicator consisting of a couple (documented national production – value in €) and totally uncorrelated to the territorial communications that gave rise to it? It would be a caricature to state this completely.

However, the lightness of the processing of information during this process, particularly by dissipating non-monetary information, suggests some adjustments. A major interest of the satellite accounts of the European System of Accounts – ESA 2010 introduced in the previous chapter is to invite this institutional approach.

5.1.1. Levels of representation and materiality

5.1.1.1. Systemic territorial accounting

Let us briefly recall here what arouses our interest in the satellite accounts proposed by the ESA 2010. From an institutional and sectoral point of view, a specialized satellite account allows the integrated analysis of productive phenomena described at the interface between different branches and between different sectors of activity. From a functional and systemic point of view, a functional satellite account highlights the users and beneficiaries of the function concerned1, which leads to the possibility of a perpetual feedback with the institutional approach.

The mesoeconomic analyst is thus able to assess the same productive phenomenon, described jointly by an integrated institutional approach within a specialized satellite account, for example that of the transport sector, and by a functional approach, for example within the health functional satellite accounts.

To build such a framework for distinguishing between specialized (sectoral and institutional) and functional analyzes, it is necessary to follow four steps in the design and establishment of a satellite account (Eurostat 2013, point 22.46).

This involves identifying (i) the objectives, uses, and needs that led to the creation of each satellite account describing a function or sector deemed sensitive to the activities covered by the territory project; (ii) the links between these objectives, uses, and needs, and the elements of the national accounts that are relevant to describe these activities; (iii) how each satellite account deemed sensitive to these activities uses relevant additional information (specific statistics, administrative sources, etc.); and (iv) how each of these accounts combines concepts and numbers into a single set of tables and accounts.

For example, if the productive phenomenon considered by the analyst is transport, the share of aggregate transport in the added value of total transport can be determined. And a correlation with the functional health account can be made to take into consideration the impacts of total transport pollutant emissions on health, and on total health expenditure.

This process can lead to the development of a summary table of key indicators that “could focus on describing the size, components and developments of the specific issue involved, or may show the links to the national economy and its major components. Extra detail or classifications relevant for political and analytical purposes may be added” (Eurostat 2013, point 22.54).

It is thus possible to envisage a mesoeconomic dashboard adapted to the evaluation and monitoring of a territory project. If we position ourselves in a functional economy approach, it could be a dashboard specifically adapted to the management of a functional ecosystem.

To continue the work described in the previous chapter (see point 4.1), it would be interesting, for example, to target the functional ecosystem resulting from the structural coupling of the functional ecosystems associated with the CIRePaT and AGREGA projects.

To this end, we would analyze separately and then jointly the issues related to the impetus given by local authorities to renovate the private tertiary real estate stock and to the improvement and management of regional resources in construction aggregates.

It is then a question of interfacing and comparing:

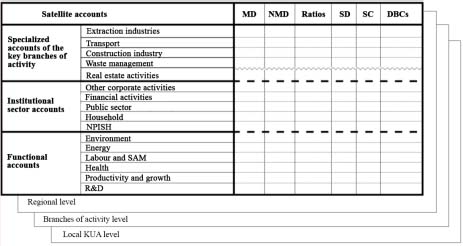

- – the specialized accounts of the key branches of activity corresponding to the activities directly involved in the central PSS offer of the territorial functional ecosystem (extractive industries, transport, construction, waste management, real estate activities, etc.);

- – a selection of institutional sector accounts (other corporate activities, financial activities, public sector, household production, and non-profit institutions, etc.);

- – a selection of functional accounts (environment, labour and social accounting matrices, health, productivity and growth, research and development, etc.)

A dashboard thus created must also include for each of these accounts elements relevant to the mesoeconomic analysis.

For each account, it is necessary to isolate from the central framework the monetary data (MD) related to this account, to compare them with non-monetary data (NMD), supplementary data (SD), supplementary concepts (SC) and different basic concepts (DBCs), relevant for the themes covered by this account. This is the purpose of the ESA 2010 satellite accounts (Eurostat 2013, points 22.06–22.08).

Table 5.1. Proposal for the organization of ESA 2010 accounts for the creation of a dashboard adapted to the evaluation of the relations between the aggregates sector and the impetus given by local authorities to the renovation of the private tertiary building stock (Morlat and Lusson 2015)

Focus can then be made.

On the one hand, for reasons of scalability, i.e. to scale up during an analysis that leads to representations of phenomena considered both at the regional level and at the level of local KAUs.

On the other hand, for reasons of granulosity in the analysis of sectors of activity and the specificity of the interests brought to the information, i.e. – if we wish to mobilize this notion at mesoeconomic level – for reasons of specific materiality attributed to this information when analyzing branches of activity. For example, we will not be interested in all construction industry accounts, but the NAF 23.61 activity “manufacture of concrete elements for construction” will be of particular interest to us.

The construction of such a dashboard thus materializes the convergence of managerial and accounting meanings of the materiality of economic information. It ensures that what is “concrete and significant” – i.e. “material” – for politics at the territorial level is also significant for the national accountant who interprets and represents that territorial level.

It is precisely this convergence that accounting standards prohibit at the level of micro accounting, by inducing, while it is not their role, financialization singularities: points by which non-monetary information is disconnected from financial analysis. And it is this convergence that systems such as CARE® would allow to foresee (see section 4.2.2.1).

However, even before innovative systems are institutionalized, considering the accounting representation of the realities of a territory in a functional economy logic does not belong to a hypothesis totally disconnected from the field of possibilities.

5.1.1.2. Characteristic and related products

For a given functional account, the ESA 2010 distinguishes between characteristic products and related products, which makes it possible to address the issue of the multifunctionality of the goods and services produced.

Characteristic products are considered as typical of the domain covered by the functional account. They are described by their mode of production, by the types of producers involved, by the types of labor and fixed capital employed, and by the profitability of the production process.

Connected products are considered relevant without being typical of the function described by the functional account, either because of their nature or because they are classified in broader product categories, and their mode of production is therefore not specified in that account.

Some products are likely to appear in different functional accounts; this results in a partial overlap of national expenditure for the functions concerned, with all the potential double counting issues when aggregating for GDP calculation.

The Eurostat text (2013) takes the example of the functional health account: health services, administration, education and R&D in health are considered as characteristic products; patient transport, pharmaceuticals and other medical goods such as glasses are connected products, while medical research in higher education is a relevant product for both research and development, education and health satellite accounts.

Consider another area, for example energy and thermal renovation of a building: energy performance flows could be interpreted as characteristic products of the energy accounts. The reduction of health expenditure related to indoor air quality would then be a connected product, while the impetus for such renovations by a community – considered as functional production – would be included in particular in the functional accounts for environment and energy and would be compared with data from the key sector account for real estate activities, etc.

And if we now look at the functional coupling of our case studies – the productive phenomena addressed by the CIRePaT and AGREGA projects – in order to propose a structural coupling through accounting, it might be interesting to consider the products of the renovation of the private tertiary park as connected to the products considered by the environment account. This would in particular make it possible to address the link between a potential generalization of renovation strategies on a regional scale, and a reduction in GHG (Greenhouse Gas) emissions due to the transport of aggregates.

At a time when public authorities are grasping “massive data” and digital algorithms, such a level of accounting detail is becoming accessible.

It is up to INSEE, in its new version of the accounting framework to be published by 2025, to propose for each functional account a new nomenclature of characteristic products and connected products. This is possible: “the extension of the key sector depends on the economic circumstances and the requirements for policy and analysis” (Eurostat 2013, point 22.35) and the “precise borderline between characteristic and connected products depends on the economic organisation in a country and the purpose of a satellite account” (Eurostat 2013, point 22.27).

INSEE also considers that the change in the “base”2 that accompanies the implementation of the ESA 2010 requires “a review of the methods, nomenclatures and statistical sources used by national accounts, so that they can best reflect economic realities” (INSEE 2014).

However, the production of new classifications of characteristic and related products is inseparable from a question of legitimacy to establish conventions, for example measurement conventions involved in qualifying the impacts of increased recycling on aggregate transport modes.

The question of institutional contours also arises. When designing the “G4U” tool dedicated to assessing the sustainability performance of the territorial anchorage of the aggregates sector on the ePLANET.Blue portal, we had to distinguish between the activities that make up this industrial sector and those that do not (see section 4.1.2.1). And for this purpose we have mobilized the Nomenclature d’Activités Française (French Nomenclature of Activities – NAF) Rev.2.1 (INSEE 2015b), of which different classes have been selected, arbitrarily, in order to represent the global panorama of activities considered relevant because they are involved in at least one of the four phases of the aggregate life cycle (production, transport, use, recycling).

However, the definition of this scope, and that of the nomenclature of characteristic and connected products, is not necessarily an arbitrary choice, nor is the production of qualitative or quantitative indicators declined in such a way as to describe the four phases that we have just mentioned. These conditions of an expert (and not contributory) use of the portal in the laboratory were, as we noted, an exception for prototyping purposes.

The KerBabelTM suite of tools available on the ePLANET.Blue portal is dedicated to a contributory approach. It would make it possible to support collective practices of representation of the system associated to the aggregates sector. Contributors would thus be invited to describe together the activities of which it is composed, to produce the indicators and meta-information that qualify these activities, and to put these indicators in context to document-specific and -related products in the ESA 2010.

The articulation of the KDM deliberation matrix, the KRG representation grid and the K4U multi-criteria evaluation algorithm co-production tool can provide the basis for the connection and alignment between micro and extra-financial accounting systems, and the structuring of MD and NMD in the ESA 2010 satellite accounts.

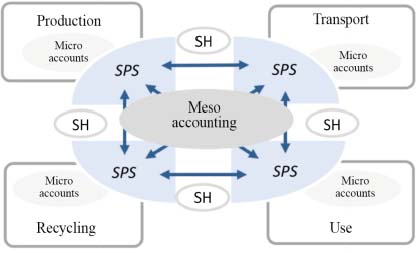

Figure 4.7 describes, for example, how deliberations involving stakeholders (SH) in the regional aggregate supply chain can lead to consideration of the effects of a transaction attached to one of the regional aggregate supply chain’s PSS on the “rest of the world”, as well as the effects of the “rest of the world” on that transaction. This includes reconciling integrated analysis and functional analysis at the micro level, and then considering a mesoeconomic link between performance indicators produced by stakeholders and NMD from the ESA 2010 satellite accounts.

Figure 5.1. Trans-scalar representation (micro–meso) of the cost systems associated with the IIe-de-France supply chain for construction aggregates (Morlat 2016)

The main difficulty of the exercise is that accounting and information systems (ISs) in general are subject to the methods used by valuation practices. If monetary and non-monetary information are separated even before contractualization, it is not possible to report on their relationship. Together, however, they constitute economic information. When they are separated, they become data again.

5.1.2. Intangible assets and performance contract

5.1.2.1. Sclerosing financial valuation traditions

At least four approaches to the financial valuation of immaterial capital can be distinguished: by historical costs, comparables, discounted cash flows, or real options.

- – The historical cost approach is rarely used because companies keep a few records of their investments in a given intangible asset (Fustec et al. 2011). What we have described of the CARE® approach, which is a historical cost valuation method, is intended to counterbalance this trend. The monitoring of capital and its management, operationalized by spokespersons (see section 4.2.2.1), involves keeping inventories of indicators and meta-information.

- – The comparable approach, already discussed with regard to the value of a building (see section 4.2.1.1), defines the value of an asset on the basis of current transactions involving an asset of the same type. To be reliable, this type of method requires a very dynamic market (Fustec et al. 2011). This approach is totally ineffective in terms of functional economy. An immaterial asset is formalized with regard to the services it establishes, services whose recognition procedures depend on the representation of a territorialized and detailed functional production. Intangible assets are therefore incomparable with each other – whether the market is dynamic or not.

- – The discounted cash flow approach (royalty, excess profit, direct return value methods) is the most commonly used. Fustec et al. (2011) provide two fundamental criticisms. On the one hand, it is almost impossible to justify the allocation of a flow to a given asset or set of assets. On the other hand, the actuarial approach is characterized by strong, arbitrary and sectorally defined assumptions. These limitations are amplified in the interorganizational perspective of a functional economy. While it is relatively easy, in the context of a PSS, to associate a flow with a service contract, the intangible assets necessary for the functional production that underpins the viability of this service are distributed within the functional ecosystem. This dynamic networking of the means of production, and the socioeconomic and ecosystem nature of this network, accentuates the uncertainty regarding actuarial assumptions.

- – The real options approach helps to perform value calculations in an uncertain and non-probability environment. Considering the availability of an immaterial asset as a real option makes it possible to establish cash flows that depend on the evolution of the risks associated with that asset. This approach provides flexibility and a better match to the discounted cash flow approach, which refers to pre-established parameters. However, it is only used marginally: based on the net present value (NPV) of the immaterial asset underlying the real option, it implies knowing a value of this underlying asset excluding uncertainty (Fustec et al. 2011).

From a functional economy perspective, however, this method is not without interest. The asset risk approach can be considered as part of a deliberation, a shared representation construction and a multi-criteria evaluation (e.g. on the ePLANETe.Blue portal.).

For example, it is possible to consider a central PSS offer − based on a market-sanctioned business model and associated with identified intangible assets, and then to consider as real options the contributions of potential contributors3. The valuation of the real option then focuses on the risk of losing the possibility of permanent business continuity, or the possibility of its development.

In part I of their Thesaurus Capital Immatériel, Fustec et al. (2011) propose a complementary approach: integrating non-financial rating into the methods of financial valorization of intangible capital.

They consider that an asset is a complex entity whose value depends on the condition of its main components, which may be characterized by different variables linked to indicators derived from non-financial valuation. It is then a question of identifying the main components of an immaterial asset under consideration, then identifying and calibrating a set of indicators associated with the variables that characterize it. An algorithm then aggregates the results of the information from these indicators in order to assign a performance score to the asset under study.

This proposal is at this stage fully in line with what we are suggesting. The algorithm in question and the work of describing an asset by its main components through ad hoc indicators, is a fairly similar approach to that used by the K4U tool of the ePLANETe.Blue portal.

One difference is that the approach of Fustec et al. (2011) is exclusively normative, and not contributory, as it is the vocation of ePLANETe.Blue. The descriptive indicators of the assets of the thesaurus approach are expertly determined by the actors of the organization whose immaterial capital is assessed.

Another difference is that the performance representation horizon on the ePLANETe.Blue portal is multi-criterial: the K4U algorithm will always provide at least a representation of a system’s performance along several axes. The Thesaurus Capital Immatériel reduces the diversity of non-financial information relating to this asset to a single monetary reading.

The fundamental point of divergence with our approach is of course not directly related to this monetarization: the purpose of the algorithm proposed by this thesaurus is to financially value an intangible asset. Our disagreement is with the method.

The financial valuation proposed in part V2 of this thesaurus (Fustec et al. 2015) is based on the replacement cost method. It is a mathematical calculation based on a durability coefficient based on an estimate of the lifetime of the benefits conferred by the asset, and on an asset condition coefficient based on a formula based on a score obtained using the algorithm described above.

The net replacement value of an asset is then obtained by the formula Vi = Cri × (1 − Cei) × Cpi expressing, respectively, the replacement cost of asset i, the condition coefficient of asset i and its sustainability coefficient. This is therefore a factorization and total deterritorialization of valorization, which has nothing to do, for example, with the logic of negotiating maintenance and renewal costs proposed by CARE®.

Worse still, Fustec et al. (2015) propose to calculate the value of the company in this way, which is supposed to be deductible from the sum of the value thus attributed to its immaterial assets, which ignores the consideration of productive systems, i.e. how the influences of these different assets combine in the business process.

Another approach, that of Bounfour (2000), based on an idea by Edvinson and Malone (1997), makes a distinction between a static value and a “Intellectual Capital Dynamic Value” (IC-dVAL®). The method implies that a static value of the immaterial capital is defined in advance. To this end, three methods are possible: the difference between stock market valorisation and assets on the balance sheet4, the analysis of goodwill5, or the calculation of Tobin’s (1969)6 Q coefficient. The dynamic value of the company’s immaterial capital is then obtained by weighting this static value by an overall performance indicator (OVI).

The OVI is a synthetic index7. It aggregates the results of partial performance indicators: resources and skills (RSI8), processes (IP9) and output performance (IOP10). These partial performance indicators are provided through a sector benchmark to assess how an improvement in the OVI index will affect, with a certain lag, the valuation of intangible capital (Bounfour and Epinette 2006, p. 176).

Figure 5.2. The five drivers of governance versus management and performance indicators. Adapted from Bounfour and Epinette (2006, p. 200). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/morlat/sustainable.zip

The OVI index therefore only makes sense from an iterative and comparative perspective (Bounfour and Epinette 2006, pp. 194–195). It makes it possible to judge the interest of managerial actions on the organization of activities, and the impact of this organization on the value of immaterial capital11.

An obvious limitation to the application of this method in the context of functional economy is that the benchmark aimed at positioning the company in relation to its external environment is sectoral. The study environment, the one by which the performance of immaterial asset management is qualified, is then intrinsically limited to the sphere of the market economy. This makes it possible to understand only some of the entities that make up the functional ecosystem.

Moreover, if we position ourselves in a functional economy model, evaluating business performance through a benchmark logic is paradoxical. This logic is associated with the idea of comparison and competition in the same sector, whereas the co-implementation of a PSS involves not only competition but cooperation and, much more, concerted specialization. This specialization leads to an evolution of companies toward specific organizational patterns which, deviating from sectoral uniformity, render the very basis of a benchmark obsolete.

Without their association being sufficient, the two approaches Thesaurus Intangible Capital and IC-dVAL® can be considered as complementary. The Thesaurus Capital Immatériel makes it possible, to a certain extent, to financially value key elements of the company’s integration into the functional ecosystem, even though the company does not have the property of these elements12. The method of analysis of a “Intellectual Capital Dynamic Value” (IC-dVAL®) contributes to indicating how the company’s managerial choices promote the sector integration performance from which it benefits.

These two methods, although neoclassical in inspiration, therefore contribute to legitimizing, from the point of view of the company that refers to this paradigm, the contributory investment made for the creation and management of the functions supporting the co-implementation of PSS within a functional ecosystem.

In our opinion, it is not a question of systematically opposing neoclassical and socioeconomic approaches, but of proposing an appropriate, i.e. balanced, coexistence system, thus avoiding the capture of the territorial political debate by a deterritorialized financialized market.

To this end, the main limit to the valuation of intangible capital, linked to the notion of control inseparable from the concept of microeconomic assets – a limit that CARE® also faces, for regulatory reasons – must be overcome.

Certain immaterial elements – in the accounting sense – fall within the direct and autonomous control of an entity. It may then be interesting to make functionalist correlations between immaterial assets not recorded on the balance sheet and tangible and intangible assets that are “material” and therefore can be recorded and then valued by the traditional accounting process. This is what all the methods we have described consider from different angles.

Other elements of immaterial capital are under shared control within the functional ecosystem. Their valuation is then carried out on the basis of an analysis of the functional interactions between utility applicants, producers of physical goods, suppliers of these goods, market intermediaries, regulatory institutions, etc. therefore within the framework of a PSS. Such a valuation is difficult when the company considers itself, from an accounting point of view, as an independent entity. However, with the exception of CARE®, the methods we have just described – aggregating and centralizing – induce and are generated by this type of perspective.

It is therefore necessary to strengthen the structuring of economic information, and more particularly the comparison of MD and NMD at the microeconomic level. This structuring cannot be entirely driven by accounting innovations – or at least we should not wait for their institutionalization to strengthen the quality of economic information. So if the immaterial is not yet fully taken into account at the entity level, it can be contracted at the territorial level, between several entities. We return here to the desire mentioned above: to make the link between entities the centre of information processing, in order to counterbalance the singularities of financial valorization that exercise, from the entities’ general accounts, a power to capture economic representations.

5.1.2.2. Innovative contractual practices

The environmental appendix to the rental lease, or “green lease”, is a tool for enhancing the energy efficiency of private commercial buildings. It was imposed by article 8 of the Grenelle II law13 on leases concluded or renewed as from January 1, 2012 – and then made applicable to leases in force on July 13, 2013. This appendix concerns premises with more than 2,000 m² of office or retail space.

The purpose of this system is to help limit the discrepancies between theoretical energy performance – contractualized prior to renovation work, and therefore intrinsic to building renovation – and actual results.

These differences are mainly related to poor communication between owner and user. They may also be due to discrepancies between design choices and building use strategies (facility management failures, poor calibration of operating teams, loss of information between construction and operation, etc.) or to changes in user behavior, depending on the economic situation, even though the use for which the building was designed remains unchanged (Catarina and Illouz 2009; Newsham et al. 2009; Zgraggen et al. 2006).

For the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD 2008), reducing such gaps implies considering existing differentiations in terms of risk, returns on investment and energy intensity depending on the activity. This requires a systemic approach to the user’s business, specific audits of system/user interfaces14 and the use of a shared incentive system between owner and tenant.

More generally, an approach to improving the energy efficiency of a building only makes sense when it is accompanied by an optimization of uses. This is what we have illustrated by referring to the mechanisms of formation of the “green value” (see section 4.2.1.1).

In practice, the environmental annex scheme aims to encourage a joint effort between the users who rent a building and the owners who own it. It provides a contractual response to this problem by systematically communicating between tenants and landlords on the conditions for the good achievement of the energy performance of the premises15. Tenants and owners together draw up an assessment of the evolution of energy and environmental performance according to a frequency that they determine together. On the basis of this assessment, both parties commit themselves to an action program16.

It should be noted here that this communication could perfectly be accompanied by a contributory web support such as ePLANETe.Blue (see point 3.2). Tenants and owners (knowledge owners) discuss the determinants of energy performance (issues), take stock by mobilizing the methods that suit them (tools) and build an action program (scenarios).

In addition to communication in the strict sense, this system encourages the tenant to facilitate access to the owner’s premises for building and energy equipment improvement work. It also makes it possible to predict the conditions for any profit sharing by the tenant in terms of savings made, for example in terms of expense control and management of its institutional image.

The environmental annex is a strictly incentive system, not coercive, but which requires a dialogue over time17.

The advantages of the framework thus established could, to some extent, be addressed with reference to agency theory (Ross 1973; Jensen and Meckling 1976; Akerlof 1970). The environmental annex makes it possible to minimize situations of information asymmetry,18 moral hazard and anti-selection19. However, we will continue to mobilize the concept of double contingency (see section 3.1.2.1), in particular because the co-implementation of performance around technical interlinking/uses prevents a principal and an agent from being distinguished.

In any case, this environmental annex scheme is one of the “cogs” of the green value formation mechanism in tertiary rental property.

The other mechanism whose characteristics we would like to highlight is the energy performance contracting (EPC).

It is a “contractual agreement between the beneficiary and the provider of an energy efficiency improvement measure, according to which investments in this measure are made in order to achieve a level of energy efficiency improvement that is contractually defined”20.

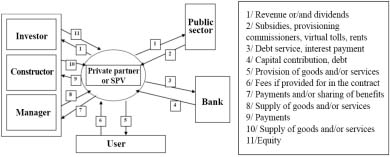

EPC is a generic characterization, defined at Community level, which applies to both public procurement and public–private partnerships (PPPs)21.

This type of arrangement allows a public entity to assign to a single private partner the responsibility for a multitude of varied tasks in a global contract that may include design, financing, construction, renovation and/or management of one or more works or services.

Figure 5.3. Real and cash flows in a PPP. Adapted from Zadra (2010)

A potential interest of this type of contract is the contractual guarantee of energy performance, accessible via the public procurement approach and via the PPP approach.

If the choice of awarding the contract is the same as the traditional public procurement, the EPC is declined into an Energy Efficiency Public Procurement Contract (EEPPC). In this case, “Services”, “COM” (construction, operation, maintenance), or “DCOM” (design, construction, operation, maintenance) EEPPCs may be associated with the use of certain performance guarantee incentive clauses. These guarantees may be long-term for COM or DCOM EEPPCs.

If the choice is that of PPP formalism, the EPC is declined into an Energy Efficiency Partnership Contract (EEPC). Performance guarantees are then of the same order as those made possible by the EEPPC, but unlike traditional public procurement, the investment can be ensured by the private partner. The achievement of performance may then condition part of the reimbursement by the public entity, which reinforces the incentive.

Another potential interest of the EPC lies in the association of the global approach to design and/or financing with a particular procedure – competitive dialogue22.

This procedure allows the public entity to define or develop – with a number of candidate consortia admitted to participate in the dialogue – one or more solutions likely to meet its needs.

Applicant consortia put out to competition are invited to submit a bid to propose solutions in terms of construction methods, value analysis, service management, financing and provision of appropriate partnership services.

This dialogue can take place in several consecutive phases. On the basis of the proposals of the first phase, the public person may reject a candidate, and constitute a selection of the different options proposed by the others. For example, it may select technical scenarios considered by one candidate while suggesting that they be carried out using a financial engineering solution developed by another candidate. Thus, from one phase to the next, the public entity can develop the candidates’ studies and projects to an increasingly precise and detailed level.

After one or more phases, a consortium is selected (the others can be compensated). The public entity will work with this to establish the functional and operational maintenance program, as well as the draft contract, and the proposal for a risk-sharing matrix that will incorporate the clauses of the performance contract.

This approach has significant potential advantages, provided however that it goes beyond certain limits that are not specific to it, but that hinder any contractual approach and any co-production approach.

The first advantage is to create, through the competitive dialogue process, a close relationship between the public entity and the private partner’s design team. This can reduce information asymmetry ex ante, promoting a balanced contractualization of performance guarantees and associated incentives, and improving the control of moral hazard23 and anti-selection24 risks.

Second, competitive dialogue reduces uncertainty for the private partner about possible unforeseen changes; avoids the production of multiple, costly and sometimes inneffective design and financial evaluation studies; and allows confirmation of technical interest before the call for tenders on the financial feasibility of the project. This dialogue thus potentially encourages the opening of the market to new entrants.

The limits of this approach to contractualizing performance are “quite simply” due to the ability of the actors to really enter into dialogue, and to maintain this dialogue over time to avoid a misalignment of costs following a dissipation of economic information.

Performance contracts are neither good nor bad tools, it is the transactional universes in which they are mobilized that determine their scope. And it is the perimeters of the reading grids of this scope, this performance, that determine the value of the projects they legally frame.

5.2. Taking the measure of the territorial heritage

Collective design, implementation and evaluation approaches transform the representations of production processes, and everyone’s understanding of the influence of the behaviors of other actors that influence these processes. The notion of memory is specific to each co-production locality, and inseparable from the recognition and contractualization of a partner’s role in achieving a common performance. It is a shared memory, which can be activated again and enriched in future co-productions.

By referring to the energy performance contracting and the environmental annex to the private tertiary lease – known as the “green lease” – our aim was not to specifically highlight the purpose of these mechanisms but to highlight their process. The energy efficiency improvement operations they support are based on real co-design, as part of a dialogue that is not an option but a step, institutionalized at the heart of these systems, i.e. regulated, and which feeds into contractualization.

What interests us in these devices is the testimony of their existence. The institutionalization of a dialogue confers on the contractual process the advantage of a co-evolution of representations of the determinants of energy performance (technical specificities of the building, conditions for carrying out each other’s jobs, etc.) – a co-evolution that is difficult not to compare with the characteristics of a cooperative transaction (see section 3.1.2.1).

The problem that appears at first sight, linked to this double co-evolution, concerns the notion of microeconomic financial risk. If the dialogue is based on shared representations and real co-design, monitoring and evaluation capacities, then the contract provides both parties with a relatively reliable framework for understanding the expected benefits. If this is not the case, the transactional approach may be captured by one of the parties for opportunism, or diverted due to a disengagement and/or incapacity of one of the parties, leading to a negative or zero-sum game.

A more fundamental problem, which is part of larger spaces and times of valorization, is linked to the dissipation of economic information induced by the capture or misuse of a microeconomic transaction.

The transaction can be the process of a financialization singularity, i.e. leading to a point of separation of MD and NMD and annihilation of the possibilities of access to knowledge of the specificities of space and time of the phenomena on which they are based, thus dissipating economic information. On the contrary, it can be a place to document the relationships between these data, i.e. to preserve the meaning conferred on the object of this transaction, as evidenced by the act of producing a contract that can embody a repertoire of indicators and meta-information inextricably linked to a monetarization locality.

In other words, the question is whether the transaction will produce or destroy the territorial heritage.

5.2.1. An irreducible interface between performance and profitability

5.2.1.1. Comparing prices, costs and values

The most obvious limitation to the application to the functional economics of the methods for financial valuation of immaterial capital described in components I and II of the Fustec et al. (2011, 2015) Thésaurus Capital Immatériel is that a functional ecosystem does not consist solely of private companies. Institutions and stakeholders make their decisions by giving financial criteria often less importance than companies.

Another shortcoming of these methods is related to the notion of materiality. In a managerial sense, the materiality of information depends on the level of knowledge of the interorganizational process of value creation. Methods that are based on intraentity managerial tropism and financial rationality that are too strong, or that induce such tropism, limit this knowledge.

In cases of this type, the data deemed strategic by companies remain based on a transitive, rather than a functionalist, utilitarian approach to interorganizational space. And immaterial capital valuations based on this approach only allow a tiny fraction of the information about the relationships between entities that make up the functional ecosystem to be reconstructed. As a result, a pooling of the information produced by each of them could not guarantee the level of information quality required for collective governance of the functional ecosystem.

This situation is due to a structural inadequacy of the territorial economic IS, which does not make it possible to free the actors from the omnipresent confusion between prices, costs and values.

A service provided under contract with an internal partner in the functional ecosystem, during a transaction associated with various performance objectives and based on the expression of plural value judgments, is associated with a price in euros, a negotiated price. This price, which could be associated with an exchange value within the strict framework of the market transaction, no longer exists “on its own” when the transaction is considered as an internal process within the functional ecosystem.

By fitting into a greater horizon of wealth than that of the market horizon, the monetary representation of the expectations of the contractualized service integrates a new space of negotiated composition of value: that of the collective design of multifunctional productions. The meta-information associated with the monetary indicator that provides information on the contractualized market price level at the microeconomic level is then fundamentally recomposed. They must be linked to other information in order to feed the collective management of the functional ecosystem, i.e. the integrated maintenance and enhancement of its functions.

In other words, price information remains, particularly in the commercial contract, associated with meta-information describing the conditions of contractual performance. But when considered by an analysis conducted at the level of the functional ecosystem, it must be “enriched” by other information and meta-information relating, for example, to the impact of the performance of the contract on a function considered as a shared resource and whose modification affects the individual and collective performance of various entities in the territory – including the parties to the contract – and the cost of achieving that performance.

The monetary representation associated with a transaction carried out by actors who do not identify themselves as belonging to the functional ecosystem is therefore not associated with the same value system, nor with the same IS, as a monetary representation associated with the same transaction by an actor who would evaluate the latter’s influences on the functions and processes of this ecosystem.

The first monetary representation is an exchange value in the market sense. The second is not, since the transaction with which it is associated cannot be disconnected from the actor’s contribution to the collective management of productive phenomena that are favorable to his/her activity and whose recognition mobilizes systems of social representation and specific areas of enhancement.

Both – the market exchange value and the exchange value necessary to achieve subjective and contextualized functional benefits – are different from a third monetary representation of the impacts of the transaction, which may for example be the collective one formulated collectively at the level of the functional ecosystem itself, following a deliberation between the actors in charge of its governance.

In short, and we refer here to Chapter 1 (section 1.2.2.2), if in a strictly market economy the exchange value tends to impose itself as a standard of wealth on the horizon of the universal (captured by the market) and tends to erase the spaces of representation of reality at the level of the links between the singular and the particular (embodied by the functional ecosystem); the phenomenon of organizing information within a contract – which results from a dialogue – on the other hand structures the economic representation space by resituating the origin of the MD considered by the market in a locality where wealth is represented by NMD.

In other words, combining MD and NMD in the contract makes it possible to resituate and document part of the economic information expressed within the functional ecosystem and then dissipated by financial accounting. The territory of economic representations is no longer a simple atomization of financialization singularities. It is once again forming a social system, and contracts are the “frontier objects” between this territorial social system and the market.

Talking about exchange value outside of market transactions is then a semantic shortcut that leads to important pitfalls, if the conditions of monetary representation are not specified.

The meta-information associated with the monetary indicator is definitional of the type of territorial economic organization. They change when moving from one organization to another, for example from the “market” organization to the “functional ecosystem” organization, which intersect each other but do not overlap.

Collective governance of a territory implies a reflection in terms of the “costs” of maintaining and achieving functional ecosystem organization, or more precisely the costs of maintaining and renewing the functions of this system through collective selection and capacity building for sustainable multifunctional production (use value). The constituent entities of this organization must also, because of their membership of the market economy, reflect on the terms “price” for the acquisition of resource services (exchange value).

What is usually represented as the same economic object – here the service – therefore corresponds to several representation systems, each consisting of a single monetary indicator, common to all these representation systems, but associated in each of these systems with various non-monetary meta-information.

Moreover, within an organization – microeconomic or territorial – this same monetary indicator is combined with several meta-ISs, depending for example, on whether it is a question of positioning this monetary indicator separately but jointly in a cost and price analysis (which is the role of accounting).

Thus, not only do two actors never have the same representation of a service they have just contracted together, but the monetary price agreed for the execution of this contract is associated, for each of them, with several different ISs.

5.2.1.2. Functional ecosystem and double entry

Accounting practices are intended to reconcile the points of view of the actors involved in an internal transaction within the entity: the informational continuity between maintaining its capital (liabilities) and valuing its commitments (assets).

The double entry logic compares assets and liabilities, distinguishing between information relating to what constitutes mobilizable capacity and information relating to what has made it possible for this capacity to exist and must therefore be repaid – this while establishing the principle of accounting identity: at the end of the financial year “with respect”, the value of the monetary indicator that describes the balance sheet liability must be equal to the value of the monetary indicator that describes the asset.

The completion of the entity’s internal valuation process thus leads to the association of descriptive ISs for different objects with the same monetary indicator value.

However, this formal coexistence of multiple non-monetary signifiers attached to the same MD stops at the microeconomic accounting balance sheet. Meta-information, abandoned in the appendix to the accounts and in the contract, often provides only low levels of detail and is not necessarily compatible in terms of categories and types of meta-information. This characteristic makes the territorial area a place for dissipation of economic information (see section 2.1.1.2).

We will propose methods for analyzing a process of internal valuation within the territorial functional ecosystem, the closing of which leads to the association of descriptive ISs for different objects with the same monetary indicator.

More specifically, we will suggest applying the concepts of double-entry and accounting identity to the assessment of a territorial capacity to compare a monetary indicator with non-monetary information derived from representations made at different territorial levels.

Let us return to the example of the green value of a renovated building, expressed in euros. It does not have the same information potential at the end of a transaction involving an HQE (French High Environmental Quality) certificate, real estate expert, lessor and lessee, as the much less wealthy one it has once consolidated in the accounts of a holding company. In a similar logic, the energy expenditure related to the road transport of aggregates is potentially more valuable information in a carrier’s micro accounts than it is in the national accounts of the transport sector. At the micro level, it can, for example, be compared with the distances traveled and the GHG emissions specific to aggregate transport. This information potential is dissipating at the macro level, which will consider freight transport as a whole.

While the purpose of the assessment is solely to assess the creation of economic value added at the territorial level, current mesoeconomic consolidation practices are satisfactory approximations. Considering that all micro transaction situations are similar, and that the contractualized valuation levels resulting from them can therefore be totally aggregated, does not disrupt the purpose of the analysis, which is to have an instant monetary representation of the efficiency of the productive system: GDP.

If, on the other hand, as suggested by the guidelines of the European System of Accounts ESA 2010 (Eurostat 2013), national accounts are also a tool at the service of political economy, the knowledge of the specificities of micro evaluation situations and objects must be preserved. For example, the public contracting authority may wish to jointly monitor microeconomic efforts to support the impulse of renovations and the evolution of regional aggregate traffic in order to integrate these two management areas into integrated planning.

More generally, it is a question of ensuring that each actor has access to a better knowledge of the cultures, practices, referentials and assumptions attached to the valuation situation that gave rise to a monetary representation. This monetary representation would emerge from the “information black hole” where it is maintained by the pre-eminence of financial valuation practices and aggregation between the micro and macro levels. Financialization and aggregation tend to extract monetary information from the plural social value system in which it was constructed, i.e. from its monetarization locality.

In other words, in our view, monetary representation must be placed in a continuum of values, spaces and time within which the overall level of information dissipation would be closer to that which characterized the initial valuation situation. This would reduce the current propensity for financialized and deterritorialized capture of economic thinking.

What meaning should be given here to the concepts of assets and liabilities? In financial accounting, liabilities are a resource for financing assets.

In terms of the accounting of a territorial functional ecosystem, the capacity recorded on the asset side will be the one that allows absolute decoupling. It will correspond to the informative and cognitive territorial conditions of effectiveness of a collective governance of production and valorization based on the articulation of the three levels of decoupling (see section 2.2.2.2). The capacity described in the liabilities of the territorial functional ecosystem accounting must, in our opinion, correspond to a state of adequacy of the ISs mobilized by each of the entities of the territory, to constitute itself as a functional ecosystem and to ensure its governance together under conditions valued on the assets.

We will formulate things as follows:

- – the assets of the functional ecosystem will be considered as the set of information and cognitive capacities enabling entities to maintain and improve the territory’s ecosystem, technico-economic and socioeconomic processes;

- – the liabilities of the functional ecosystem will be considered as the set of information and cognitive capacities enabling the entities to maintain and improve together the particular ecosystem, technico-economic and socioeconomic functions supporting their own activity.

Considering the state of the informative and cognitive capacities necessary for territorial processes as the asset of the functional ecosystem, and the state of the informative and cognitive capacities necessary for the availability of territorial functions as its liabilities, leads us to consider this territorial accounting from an “external–internal” perspective.

This involves assessing whether entities engage in transactions related to their activity (functional ecosystem liabilities) with information made up of data whose structure is likely to be mobilized by territorial governance (functional ecosystem assets).

In short, it is a situation of cognitive dissonance – a state of tension felt by a person in the presence of cognitions (knowledge, opinions or beliefs) incompatible with each other (Festinger 1957) – that must be diagnosed at the scale of the functional ecosystem, between individual and collective interests.

5.2.2. Territorial informative and cognitive assessment

5.2.2.1. Triple heritage identity

The way in which an entity is involved in a deliberation on the representation of a collective project (assets on the balance sheet) depends very largely on the entity’s representation of the impact of this project on its own activity (liabilities on the balance sheet).

When we talk about the territorial information system (IS), we have a broad understanding – including processes, information, directories, individual and collective representations. In our opinion, this IS can be combined with a balance sheet account to monitor and evaluate the decoupling capacities it provides. And according to the proposal we have just described, the assets of this shared territorial heritage account must be assessed at the level of the territorial deliberation practices that underlie the collective management of the decoupling process, while the liabilities must be addressed at the level of the individual cognitions of the actors who lead the entities involved in these deliberations.

To propose a system adapted to this asset account, we will focus on the cooperative transaction process in the sense of Zacklad (2006, 2007, 2008) (see section 3.1.2.1), which we will bring closer to Luhmann’s theory of social systems (1982, 1988, 1986, 1991, 1995).

The transcription (political, contractual or accounting) of a transaction within the territorial IS embodies in our view the communication position – i.e. the content of territorial communication – in Luhmann’s sense. The actors in the territory are thus permanently, alternately or jointly, “coders” and “decoders” of this container, i.e. both in the position of information transmitters, and in the position of receiver pending success.

In addition, the expectation of success is – clearly and jointly – that of success for the activity specific to each of the actors, and that of the collective success of a decoupling strategy conducted at the level of the territory in question.

In a microeconomic transaction entered into by a contract, the contracting parties are not only senders and receivers, one against the other. The contract is also the communication support of a territorial communication during which the co-contractors are together in the position of issuers. They give particular meaning to the organization of monetary and non-monetary indicators within the structured communication in the contract, the price and conditions of which they describe respectively, in terms of performance.

In this position of the issuer, possibly extended to the stakeholders involved in contractual negotiation, contracting parties can “understand” the indicators that code the information they issue, i.e. give it a social meaning. For them, these indicators resonate with a set of meta-information that specifies the area of relevance, the mode of interpretation and the purpose of the mobilization of each indicator. This resonance of the indicator with the meta-IS that governed its mobilization is specific to the collective cognition of the group of actors who issued the contract. These actors have access to the repertoire – formal or informal – in the creation of which they contributed during the transaction, and this repertoire is therefore characteristic of a transactional locality, i.e. a specific sociotechnical anchorage.

The receiver of the communication medium that is the contract also gives a particular meaning to the organization of structured indicators within the message it receives. During this decoding action, he/she “understands” these indicators in a way that is not necessarily in adequacy with the communication intention that the transmitter wished to convey. The indicators resonate with a different set of meta-information, specific to the cognition and representation system of the receiver. Decoding is therefore always accompanied by interpretation on the part of the receiver.

It is in particular this association between various non-monetary meta-information and the monetary indicator to which it is associated that makes the difference between prices, costs and values – and their coexistence – within the territorial representation space.

A notion of the identity of monetary information can then be suggested. To address the discrepancy between the identity of the information encoded by the issuer and the identity of the information interpreted by the receiver, we will be guided by the principle of accounting identity.

Our approach to the notion of identity does not only refer here to the accounting terminology associated with double-entry formalism, which ensures the continuity of asset value between the end of one fiscal year and the beginning of the next. It also refers to the anchoring of the communication process within the representation space.

It is therefore not a question of mobilizing the notion of identity to express an invariance of the signified, but to qualify a capacity of the territorial IS to approach the three positions of communication in such a way as to reflect it in an integrated way. The notion of identity therefore describes the territorial continuity of the capacity to interpret communication, regardless of the level at which it is received and decoded.

To take the measure of territorial heritage – which we have described here as informative and cognitive in terms of the capacity for interpretation it confers – means first of all to locate a communication in relation to the level of its emission, in space and time. One way to approach this process is to describe how the directories mobilized by the actors involved in different cooperative transactions are being renewed.

The territorial informative and cognitive heritage associated with communication increases when the experiential content of actors and mediating artifacts jointly evolve toward a better collective capacity for interpretation. This is the case, for example, if co-contractors “code” a performance contract in such a way as to facilitate the recognition of these performances by other actors involved in the collective governance of the territory.

Taking the measure of territorial heritage then implies considering at least two types of cooperative transactions: those between co-contractors and those involving stakeholders in deliberations relating to territorial governance.

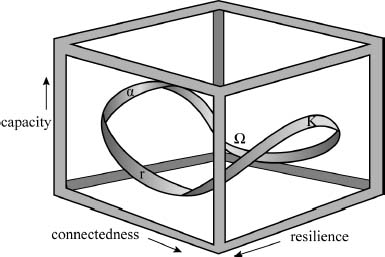

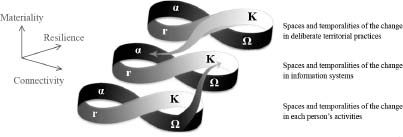

Let us now try to place these reflections within the framework introduced in the second chapter; we have associated the concept of cooperative transaction with the adaptive cycle of (Holling 1995) (see section 3.1.2.2). The description of the phases of exploitation (r), conservation (K), liberation (Ω) and reorganization (α) allowed us to jointly approach the processes of territorial representation and contractualization a functional economy.

This approach has made it possible to highlight the relationship between economic production and the production of representations of the territory – territory being understood here in the sense of a situation of coordination favorable to the combination of spatial, organizational and institutional proximitieds which are the potential of a territory (section 3.1.1.2).

An adaptive cycle describes, let us recall, a three-dimensional space: resilience, the connectivity that underlies it and the capacity it confers (Holling 1995).

Figure 5.4. Heuristic model of the adaptive cycle (Allison and Hobbs 2004). Adapted from Holling et al. (2002)

We will include the analysis of the adaptive cycle described by a cooperative transaction in the territorial representation space by considering that this space is itself structured by an IS – in the broad sense. This system makes it possible to qualify the territorial informative and cognitive heritage in terms of resilience, connectivity and capacity – by combining the latter with the notion of the materiality of information. The representation of materiality, when it is shared, is a sign of a potential for the convergence of interests, the constructive structuring of disunity and therefore cooperation in the transaction, which contributes to a strengthening of the coordination potential: an enrichment of the heritage.

The aim of the territorial informative and cognitive heritage assessment is, let us recall, to describe the state of a potential for territorial communication. It is only fully meaningful if the principle of accounting identity is addressed in three dimensions, corresponding to what the territorial IS confers, in terms of connectivity between individual and collective repositories; the resilience of information processing practices and the materiality of the information communicated.

- – The connectivity identity describes the way in which the territorial IS makes it possible to compare the indicators and meta-information mobilized by a territorial deliberation (connectivity asset), with those mobilized within the framework of each person’s own activities (connectivity liability).

- – The resilience identity describes the way in which the territorial IS makes it possible to maintain a capacity to choose information processing methods and tools adapted to the problems of collective deliberation (resilience asset), while ensuring a free coexistence of the diversity of individual representations (resilience liability).

- – The materiality identity describes the way in which the territorial IS makes it possible to document the convergences or divergences between the perception of the effects of a phenomenon taken into account during a territorial deliberation (materiality asset) and the perception of the effects of this same phenomenon during the activities specific to each (materiality liability).

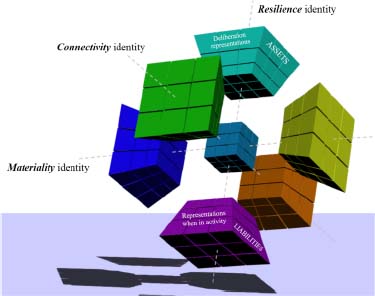

We will then speak of a triple patrimonial identity – or triple heritage identity – to describe the identity between the asset (representations mobilized within the framework of collective deliberations) and the liability (representations mobilized by the actors within the framework of their own activities) of the informative and cognitive heritage account of a territorial functional ecosystem.

5.2.2.2. Adaptive cycle and IS

The concept of patrimonial balance sheet makes it possible to approach the co-evolution between assets – information and cognitive capacities that can be mobilized collectively in a context of deliberation relating to territorial governance – and liabilities – individual information and cognitive resources that must be maintained and regenerated by each person’s own activities in order to ensure availability and renewal of the asset.

We have specified that it is the analysis of a territorial IS that makes it possible to address this co-evolution between assets and liabilities. We also noted that assets and liabilities describe, each at its own level, cooperative transactions that we have associated with adaptive cycles.

In our opinion, it is therefore necessary to consider that the evolution of the territorial IS also describes an adaptive cycle, embedded in the co-evolution of the representations mobilized during the territorial deliberations and the activities specific to each one.

Figure 5.5. The territorial information system embedded in the co-evolution of the representations mobilized during the territorial deliberations and activities specific to each one

The evolution of the territorial IS allows a new relationship to the analysis of spaces and temporalities of representation. According to the terminoly proposed by Colletis et al. (2005) concerning territorial proximities (see section 3.1.1.1), this approach consists, on a cyclical basis, of analyzing the conditions for a better combination of spatial and organizational proximities (co-evolution of territorial deliberations and activities specific to each one) and in adapting institutional proximities (via ISs).

It is thus a global, unique, adaptive cycle linked to the institutionalization of the territorial IS – understood in the broadest sense, including the informative supports necessary for the deliberations and activities of each individual – that we will evaluate.

To this end, let us mobilize the KerBabel™ Representation Rack (KRR) of the ePLANETe.Blue portal that, as we have seen, makes it possible to address the coherence between meta-information associated with indicators mobilized in a situation of territorial deliberation, and meta-information associated with these same indicators when they are mobilized within the framework of each other’s activities.

The relevance of the indicators selected for a territorial deliberation situation is assessed on the basis of a simulation of these indicators (see section 3.2.1.2).

This simulation leads in particular to a diagnosis of the capacity of the actors to mobilize these indicators because of the methods they use in their own activity. More specifically, it describes how an actor can report on the effects of a scenario under deliberation on how his or her own activity is likely to impact an issue considered in that deliberation.

The representation rack (KRR) proposed by the ePLANETe.Blue portal thus constitutes a device for measuring the value of the territorial informative and cognitive assessment, according to the triple dimension of heritage identity described in the previous section.

We will describe the informative and cognitive heritage assessment of the territorial functional ecosystem relating to the deliberation situation in terms of:

- – the connectivity between indicator repositories used in deliberation situations, and within the framework of each person’s own activity. The KRR makes it possible to determine this level of identity by calculating the presence coefficients of the indicators at the interface between the dimensions methods and tools (M) and knowledge carriers (C). The underlying hypothesis is to consider that it is difficult for an actor to participate in a collective approach if he/she cannot envisage bridges between the indicators necessary for the methods and tools for evaluating the collective approach, and the reference framework of indicators that are necessary for the methods and tools used to evaluate his/her own activity;

- – the resilience of the territorial IS in the face of the potential for capture by individual and collective representations. The KRR makes it possible to determine this level of identity by calculating the presence coefficients of the indicators at the interface between the issues (I) and methods and tools (M) dimensions. The underlying assumption is to consider that a non-resilient territorial IS is a system that does not make it possible to address the diversity of issues considered by the actors of the territory (either individually or collectively), or that gives access to insufficient information in number and/or unsuitable in their format to meet the analytical needs related to each other’s activities;

- – the materiality of the issues that can be addressed by the repositories that make up the IS. The KRR makes it possible to determine this level of identity by calculating the presence coefficients of the indicators at the interface between the knowledge-carriers dimensions (C) and the issues (I). The underlying assumption is to consider that the materiality of the issues considered is strong when actors select many indicators to describe how their own activity is sensitive to these issues, and possibly contributes to addressing them.

The informative and cognitive balance of the territorial functional ecosystem can thus be associated with what Douguet et al. (2015) call “KnoT” or “Knowledge Tesseract” (see section 3.1.2.2).

The central cube in Figure 5.6 describes a three-dimensional “KnoT” by which we can address the presence of indicators at each of the crossroads between the method and tool axes, issues and knowledge carriers – one axis per cube face.

This Knot corresponds to the informative and cognitive assessment. The surrounding cubes describe the need to establish in advance, with the KRR, and for each dimension of heritage identity, a situation of the indicators mobilized in a deliberative situation (assets of the territorial functional ecosystem) and a situation of the indicators mobilized in the framework of the activities specific to each category of actors (liabilities of the territorial functional ecosystem).

Figure 5.6. The Knot KRR associated with the informative and cognitive assessment of the functional ecosystem, broken down according to the dimensions of a triple heritage identity (visual realization with the MagicCube 4D tool; http://superliminal.com/cube/cube.htm). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/morlat/sustainable.zip

Thus, couples [indicator – meta-information] – i.e. representation systems – made available by the territorial IS, can be associated, on the one hand, with representation subsystems that are the couples [indicator – meta-information] mobilized by the constituent entities of this functional ecosystem when they are under deliberation, and, on the other hand, with other representation subsystems that are the couples [indicator – meta-information] mobilized by these same constituent entities but when they are concerned with their own activities.

This distinction-conjunction makes it possible to anchor the evolution of the territorial IS both in time and space, and to address the problems of cognitive dissonance that may arise in the event of a cognitive conflict faced by an actor.

It is therefore a question of systematizing a mapping of the potential of territorial communication.

5.3. Conclusion

The informative and cognitive assessment described at the end of the previous chapter implies taking the measure of the territorial heritage mobilized by a particular deliberation situation within a functional ecosystem. This balance provides a static picture of the level of informative and cognitive heritage of this ecosystem at a given moment: the one at which the informative and cognitive heritage balance is carried out.

In our opinion, the “respectful closure” of this assessment implies taking into account a co-evolution between individual and collective representations. We suggested that this be observed according to three axes of analysis: the resilience of ISs, the connectivity of repositories and the materiality of information. This triple heritage identity aims in particular to ensure that the adaptive cycles that drive individual and collective representation systems can co-evolve and resonate positively, without inhibiting expressions or capturing possibilities for interpretation.

An IS must make it possible to take possession of information in order to produce content with the same potential to produce a “true and fair view” of it wherever you are, at one level of territory or another, at one time or another. This is what we have expressed by formulating the interest of a territorial informational continuum: any actor should be able to measure the quality of information by being aware of the sources and context of its production in order to better mobilize it.

However, this quality of information is not expressed in precision or quantity, but in adequacy, i.e. in a report on the way in which it must be composed and presented, in order to be mobilized by other actors, in other spaces and times of representation.

Returning to the theory of social systems, we have associated the contract that seals a territorial project with one of the three positions of communication: that of communication, that is, of the container – or support – that allows the diffusion of information, which will be interpreted in the expectation of success.

This position – communication – when held by the mediating artifact that is the contract, has two particularities. It anchors Communication in the duration of the contractual commitment and stabilizes during this period an island of rationality within the space of representation of the territorial project. It mobilizes indicators to characterize the performance clauses that reflect levels of ambition and adequacy to the requirements of this project.

The contract therefore has a strong structural dimension. It contextualizes both the information mobilized during political deliberations around the ecological, economic and social dimensions of a territory’s performance, and the information mobilized during accounting valuations. Thus, the discounting logic that underlies neoclassical valuation practices (see section 5.1.2.1) by reducing to the present time the financial value of economic flows expected from an “all other things being equal” future, shatters when confronted with the dynamics of the changing contractual landscape.

In other words, the condition for the validity of the neoclassical hypothesis would lie in the theoretical acceptance and empirical observation of the non-existence of the influence of political deliberations on social representations and contractual practices. Of course, we reject this hypothesis and will on the contrary seek to qualify the ways and means of expression of this influence.