2

Information Structures Production

2.1. The value chain: an outdated representation

In a social and ecological economy of sustainable development, linkages – whether between individuals and communities or between physical elements and ecosystem functions – precede the economic good. These links are necessarily objectified at the scale of a territory, which is not very compatible with the attribution of an added value to the activity of a single institutional entity. Indeed, beyond the value of a productive phenomenon, which can only be understood in a limited way at the entity level, it is necessary to take into account the effects exerted on that entity by the activities of other entities in the territory with which it is functionally linked.

Addressing the valuation of productive phenomena then implies opening a path of theoretical and practical coexistence between neoclassical and socioeconomic approaches to valuation.

One way to do this is to return to the ontology of work that we have just described and, from this perspective, to consider that some financial work products are not financial. Financial work, as part of plural work, influences economic work that selects productions with which an exchange value can be associated. Through this selection, it excludes or supports physical and digital productions which, because they are based in territories of ecological, social and economic production, influence the plural work that takes place there and makes these productions possible.

The danger of this selective encounter is that it is disruptive. The financial component of work is part of an ethereal, globalized environment and its direct and indirect interaction with the other components of work breaks their territorial anchorage, which is not only characterized by localities and temporalities of representations, but by forms and processes of information. We refer in particular to the multi-criteria analysis of value, a practice inherent in a social group whose representations – concepts – can be captured.

However, some capitalization and transaction methods would make it possible to use the interface of the physical and digital industry to improve the quality of ecological, social and economic information, and to reintegrate financial work into territorial negotiations around value.

2.1.1. Toward a functional economy

2.1.1.1. Stationary economy and decoupling

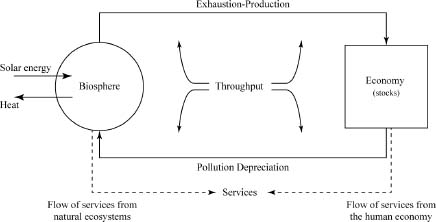

The stationary economy model proposed by Daly (1974) – an ecological economist – is based on the notion of “throughput” (Boulding 1966; Daly 1968; Georgescu-Roegen 1971). This flow describes the extraction of energy and raw materials from the biosphere, which, transformed by the human economy, is returned in the form of heat and waste.

Figure 2.1. The interface between the economic system and the ecological system (from Faucheux & Noël 1995; Daly 1991)

Stationary economy then focuses on the conditions of efficiency of service provided by an economy with a stock of material goods and a human population maintained constant at desired and sufficient levels (Daly 1974):

This relationship has the advantage of anchoring the analysis of economic value in the conditions of rigor and strong sustainability necessary for absolute decoupling (see section 1.1.2.1), but it is limited to economic– environmental interactions. It therefore does not make it possible to account for the socioeconomy of the territory by which the production of the same physical good can be associated with the production of multiple functions with recognized utility (functionality).

Entering into the details of the component (stock/flow) of this equation makes it possible to imagine the effect that a territorial reorganization of trade between units of industrial production of physical goods would have on the energy-material flow.

While detailing the component (service/stock) makes it possible to introduce the link between identifying the functionalities expected from the production of physical goods, and valuing the use of these functionalities.

These relationships are purely didactic. However, they make it possible to go further in understanding what decoupling strategies could be. This includes identifying the limits and complementarities of the technicoeconomic and socioeconomic approaches mentioned in the Introduction.

The improvement of the sobriety of material production by technological means is one of the directions of decoupling. This improvement must also and above all be based on a social and political process, which is another direction of decoupling, likely to legitimize a framework for the consumption of material goods necessary to reduce the flow of energy and materials (see section 1.1.1.2). The social acceptability of such a framework and the economic argument – including the possibility of a “loss of income” – are then of course to be taken into account.

To this end, let us return to the relationship (1) that compares the reorganization of industrial production with the possibility of an increase in the stock of physical goods with constant energy-matter flow. This relationship illustrates the purpose of the circular economy and industrial ecology: to use certain outputs of a production which, instead of being considered as waste in a linear industrial economy scheme, will be used as resources by other activities in the territory.

Eco-industrial strategies (Erkman 1997) involve sealing and closing energy and material flows, dematerializing products and services; they require incoming and outgoing pooling between processes, as well as substitution of resources, activities and products1. These strategies, which represent an opportunity to reduce costs for some actors, therefore require a high degree of territorial cooperation. While they essentially reflect the spread of the logic of ecological economics to industrial organization, the driving force behind their implementation is socioeconomic action.

The relationship (2) also highlights the fact that controlling the flow of energy and reducing the costs of industrial production of material goods is not the only opportunity for economic gains for a territory of activities. A substantial part of the success of a decoupling strategy depends on the ability to identify and promote to as many actors as possible the greatest possible number of access to as many functionalities generated by the same industrial production.

The economic acceptability of a decoupling policy is thus as much a matter of the eco-industrial approach as it is of the stakeholders’ approach (Freeman 1984),2 which involves addressing the relationship between uses and trade.

Moving from usage value (recognition of utilities) to exchange value (monetarization of the provision of access to goods and services based on these utilities) involves recomposing the relationships (1) and (2) between them.

The relationship (3) illustrates how a territorial capacity to recognize valuable functionalities is likely to promote the increase in exchange value levels through reorganization of exchanges and for the same level of material energy flow. It introduces the possibility of a decorrelation – of a decoupling – between the ecosystem impacts of the throughput, the industrial production of material goods, the availability of utilities and the exchange value that can be derived from them.

It is a kind of territorial “lever” at three levels of decoupling and can be collectively activated by recognizing the criticality of territorial functions and identifying useful functionalities. This relationship is useful in bridging the gap between the identification of an available utility (use value), the propensity to recognize the phenomenon that is the source of that utility as the basis for a service actually provided and the propensity to invest (exchange value) in the maintenance of that phenomenon.

These reflections support the developments of the first chapter: decoupling strategies should not leave out of the scope of the analysis of the social actions and political organization that frame the modalities of production and economic value recognition. New decoupling indicators must therefore be produced, in order, for example, to take into account the links between the political organization of development and the maintenance of ecosystem quality, rather than always focusing on the effects of polluting technologies.

Drawing an economic trajectory compatible with sustainable development requires methods and tools that allow us to address two directions – technicoeconomic and socioeconomic – of decoupling in their specificities and interactions.

Figure 2.2. Socioeconomic and technico-economic directions of decoupling (Morlat 2016)

The paradigm of the functional economy (Stahel 1986) allows us to focus our thinking on the point of convergence between these two directions. It suggests that the bifurcation is likely to transform, at least partially, an economy based on the ownership of the means of production of the physical good into an economy based on a social construction of intangible services.

2.1.1.2. Product–service systems and cooperation

For Stahel (1986): “A functional economy (…) is one that optimizes the use (or function) of goods and services and thus the management of existing wealth (goods, knowledge and nature). The economic objective of the functional economy is to create the highest possible use value for the longest possible time, while consuming as few material resources and energy as possible. This functional economy is therefore considerably more sustainable, or dematerialized, than the present economy, which is focused on production and related material flows as its principal means to create wealth.”

Many formulas can be considered as defining of this economy. Three of them are of interest to us:

- – Eco-efficient services (Bartolomeo et al. 2003) insist on the issue of property rights for physical products whose layout allows the delivery of services (based on functionalities induced by this layout); these products remain fully or partially in the hands of the producer who only transfers the use to his customer.

- – Functional sales (Östlin et al. 2006) include the requirement to optimize the lifecycle of products and thus encourage the integration of a wide range of social and environmental impacts into the valuation of services.

- – Product–service systems (PSSs; Goedkoop et al. 1999) constitute “a system of products, services, networks of ‘players’ and supporting infrastructure that continuously strives to be competitive, satisfy customer needs and have a lower environmental impact than traditional business models”.

The latter approach is interesting in more than one way. First of all, considering PSS makes it possible to address the relationship to ownership that is at the heart of eco-efficient services.

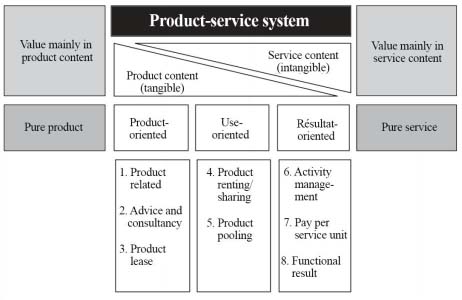

Hockerts and Weaver (2002), Tukker (2004) and Laperche and Picard (2013) distinguish three types of PSS strategies:

- – Result-oriented PSS: considering it as the most innovative, this strategy corresponds to the provision of a functional phenomenon that is specifically generated and whose costs are directly borne by the user. Here, ownership of the physical property is not transferred. This good is only a support mobilized to produce functionalities and make them available to the user. It is the utility of these features that is the purpose of the transaction.

- – Use-oriented PSS: this strategy corresponds to the provision, without transfer of ownership, of the use of a set of material goods whose articulation by the user generates functional phenomena. Physical goods occupy a more central place: they exist before the expression of a need for functionalities. However, it is always the functional arrangement of these goods that is the object of the transaction, not their marketing.

- – Product-oriented PSS: this is the least innovative and least ambitious strategy. It corresponds to a service oriented toward increasing the functionality or longevity of products after their acquisition by the user. The latter option would therefore be more a “sustainable version” of traditional after-sales service than a functional economy approach, precisely because of the transfer of ownership of the physical good (Laperche and Picard 2013).

Figure 2.3. Main and subsidiary categories of PSS (Tukker 2004)

The PSS approach is then of interest to us in which it allows the decoupling of environmental impacts and economic value. Basing valuation on the transfer of ownership of the physical good goes against the ambition to reduce the flows of materials and energy, which impact ecosystems. Thus, the more ambitious PSS strategies are in terms of avoiding ownership transfer (product-oriented and result-oriented strategies), the more decoupling is reinforced.

Finally, and as a result, the PSS approach makes it possible to address the socioeconomic direction of this decoupling. As the ambition for PSS innovation increases, socioeconomic innovation takes precedence over technico-economic innovation. Indeed, and this is crucial, the more the territorial social capacity to enhance the functionalities of the same set of physical products increases, the less the use of other industrial productions is necessary, which makes it possible to limit the throughput.

For Morelli (2006), a PSS is first and foremost a social construct. It is the link forged within a network of actors that prefigures the relationship between the energy and material sobriety of a production solution, the multiple functionalities generated, the contractualization of benefits and the economic balance of a PSS.

This link can be evaluated at the level of one of the entities of the territory, considering its impact on other entities of this territory. Baines et al. (2007) consider the knowledge of a designer-manufacturer as the basis for an integrated offer that increases the output value of a PSS, while reducing the costs of materials and other flows at its input.

This link can also, jointly, be objectified from the territorial level. For Isckia (2011), a company that markets a PSS is not to be considered as an autonomous producer, but as a leader (or pivot), in charge of orchestrating the contributions of other companies. The latter evolve within a business ecosystem (Moore 1993, 1996). They are both clients of the leader, and part of a cooperative and competitive relationship with each other, and with the leader (Isckia 2011).

During the innovation processes that characterize the functional economy, the interdependencies between actors thus generate their co-evolution. A concerted specialization (co-design, co-production and co-evaluation) puts them in a collective programming logic aimed at increasing the number of valuable functionalities while ensuring their complementarity (Vaileanu-Paun 2009).

For Vaileanu-Paun (2009), this logic of concerted specialization is more fundamentally oriented toward the conditions for the emergence of functional offers than toward an articulation and adaptation at the margin of each other’s business models. The reconfigurations required for such a degree of specificity and integration of offers then generate much higher levels of proximity and network than those that characterize Moore’s business ecosystem.

It is therefore appropriate to use the concept of a functional ecosystem (Lauriol 2007), which encompasses and goes beyond the possibilities of representation offered by the concept of a business ecosystem. The concept of a functional ecosystem makes it possible to address a higher level of organization by including companies, institutions, infrastructures and stakeholders in a single unit of analysis.

Figure 2.4. The service-based, or functional, ecosystem (Lauriol 2007)

The concept of a functional ecosystem facilitates the reading of the mechanisms of the functional economy. It allows the design of a PSS to be extended to all stakeholders interested in the functionalities associated with a production.

We will therefore use the term “productive phenomenon” rather than the term “production”, the usual meaning of which focuses on the industrial entity. We will understand here both the industrial production of material goods, its effects on physical and social territories, as well as the processes of representation of these effects which can lead to a collective approach to the selection of production methods.

It follows from this the possibility for several actors in a territory to attribute advantages of various natures to a single industrial production, thus to carry out together the valuation of several functionalities attached to the same productive phenomenon.

2.1.2. Valuing multifunctional production

2.1.2.1. Social and environmental lifecycle analyses

The beneficiaries of the functional benefits conferred by an industrial activity may be involved in a collective process of identification, qualification, recognition and valuation of these benefits.

Let us introduce the example of an ambitious program of thermal rehabilitation of housing. This is an industrial production whose main product – rehabilitated housing – can be associated with a multitude of future effects, at the scale of the production site, but also at other territorial scales.

At the building level, the rehabilitation program will create economic activity and thus contribute to reducing the monetary poverty3 of the workers involved in the rehabilitation works. It will also lead to lower energy consumption in housing, thus limiting fuel poverty, i.e. improving the residents’ ability to heat. Rehabilitation of the building is also often an opportunity to improve indoor sanitary conditions, due to the quality of the materials used, better moisture management, etc. The rehabilitation program can therefore be correlated with a reduction in the number and severity of diseases – particularly respiratory diseases – affecting some occupants of housing.

On a broader scale, a public authority may seek to identify a downward trend in the need for certain social services, following an improvement in the health status of housing. The cost reductions observed may make it possible to maintain and strengthen investment capacities that can be mobilized elsewhere, where necessary. Owners are likely to be sensitive to the fact that the local real estate market attributes a higher market or rental value to the buildings concerned by the rehabilitations than other buildings of the same type, but which have not been rehabilitated. Energy suppliers may also find it useful to carry out thermal rehabilitation projects which, by reducing energy consumption, reduce the risk of non-payment. While the choice to rehabilitate has replaced a strategy of deconstruction and rebuilding, the rehabilitation of housing also has the effect of avoiding the supply flows of new construction materials and waste flows, as well as the energy consumption necessary for these material flows, and the CO2 emissions associated with this consumption.

More generally, when a production attributed to one institutional entity produces useful effects that are recognized as such by other entities, then that production has a function from the point of view of the latter. It is useful for their own activity. And when, within a territory, a production is recognized as useful for the activity of several entities that may pursue very different purposes, this production is likely to be associated by these entities with several functions. Barthelemy et al. (2003) thus consider that a production generates multifunctional objects that jointly deliver products that can be valued on a market and others that are not.

To illustrate this concept of multifunctional production, in the previous example, the prefix “multi” describes the multitude of social, economic and/or environmental effects that can be analytically associated with the rehabilitation of buildings. The term “functional” means that this rehabilitation is not to be valued as an isolated productive phenomenon. It is part of a system made up of various actors, each likely to recognize a social, environmental and/or economic function.

The notion of multifunctionality then leads to the need to address valuation at an intermediate level between micro and meso, or more precisely at both levels, and to situate the “value chain” approach in a space of crosssectoral interactions that closely intertwine the public and private economies.

A social and environmental lifecycle analysis can accompany the awareness of belonging to a multifunctional production system. Recognizing the effects of a mode of production on the response to individual or collective issues then renews both the relationship of actors to this mode of production and the way they view the issues in their territory.

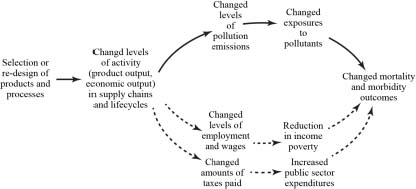

Figure 2.5 highlights the fact that an actor whose profession deals with health issues could extend the scope of analysis of what constitutes the answer to its objectives, and contributes to encouraging territorial production that is favorable to their achievement.

Figure 2.5. Paths between production decisions and human health (Norris 2006)

Norris (2006) describes here how a change in production mode can lead to a local change in the activity levels of entities related to this production, and how this change can therefore influence the product lifecycles of these entities. Figure 2.5 suggests that such functional interactions within the territorial system can have effects, and therefore impacts, on such diverse areas of concern as pollutant emissions, employment status and activity taxes.

Addressing these effects in isolation from each other would either lead to their neglect or to considering their impacts as externalities detached from the functional interactions that cause them. To approach them in that they are constitutive – through their interactions – of one or more territorial functions, implies, on the contrary, to recognize their overall influence and to construct the representation of this influence in order to determine their social significance. For example, a set of effects may, if we refer again to Figure 2.5, be given a functional role in responding to a public health issue.

The neoclassical and socioeconomic approaches discussed in the first chapter can thus be illustrated again. They induce specific representations. On the one hand, externalities to be internalized to the mathematical equations of the calculation of economic utility, and, on the other hand, a multifunctional production to be supported following a renewed focus on its economic utility.

The neoclassical concept of positive externality refers to the positive external effects of a production activity. Internalizing positive externalities aims to strengthen the economic balance of activities whose effects are recognized as having a beneficial influence on other activities in the territory. This is an approach that mobilizes monetary representation – monetarization – to correct the market when it does not allow these effects to be taken into account.

The internalization of positive externalities can mobilize the same type of instruments as that of negative externalities – such as environmental damage – described in the previous chapter (market price, or political price, i.e. tax). And as with negative externalities, this internalization is often carried out on the basis of tutelary values, attributed to a type of generic effect, i.e. in an “above-ground” way, i.e. without consideration for the specificities of the territorial context of evaluation.

This is the case, for example, of the investment aid proposed by ADEME4, for which eligibility is defined ex ante, on the basis of a profitability analysis carried out at the level of the assisted entity, and not at the level of its territory of influence5.

The idea of a circular VAT (Hua et al. 2014) proposed by the 2019 Foundation would correspond to a more specific approach to the internalization of externalities. Based on the analysis of the effects of a type of product over its entire lifecycle, this approach envisages the monetarization of these effects indirectly through an incentive modulation of the VAT applicable to the products concerned.

A limitation of these two types of practices is that at the level of the assisted entity or the taxed transaction, it is not possible to evaluate whether the purpose of the valuation is a positive externality or a reduction of a negative externality. This again raises the question of the absolute or relative nature of decoupling. Managing this decoupling implies an integration capacity that can lead to a distinction between what is a sufficiently positive effect and what is a positive but insufficient effect, and therefore an overall point of view based on a territorial strategy.

Another limitation is that current practices of monetarizing externalities do not involve actors. The effects of activities that take place in a territory are not valued by economic actors, nor, more broadly, by the actors of the territory, but by the normative declination of prices fixed at another level of representation and decision making.

The challenge then consists of reconciling an overview and an understanding of local particularities, the consideration of which diversifies the reading of functional relationships between activities in the territory. The work of valuing externalities, if it is the result of a mathematical systematization – whether this systematization is applied at the macro-, meso- or microlevel – does not integrate the reading of these particularities.

Another practice, that of valuing the intangible capital of entities – an accounting approach therefore – makes it possible to approach in a different way the strengthening of the business models of entities that have a positive impact on their territory of activity.

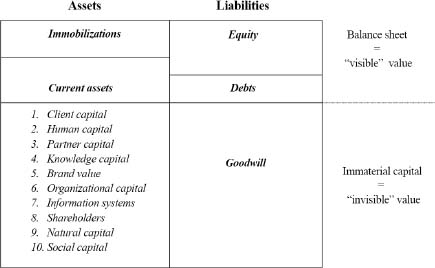

2.1.2.2. Interests and limits of the concept of immaterial capital

The concept of immaterial capital (Eddington 1990; Bounfour 1998; Fustec and Marois 2006) allows us to further understand the influence of territorial specificities on production. Multiple components of this capital can be described, for example partners, knowledge assets, information system and social assets. They represent as many capacities whose enhancement allows an entity to record in its analytical accounts the advantage conferred by its territorial anchorage, and in particular by the positive effects exerted on it by the other entities of the territory.

Investors and analysts who select information to represent the financial position of an entity obviously have an interest in taking into account the effects exerted by other entities in the territory. It would be useful to have a discussion between the entity producing the beneficial effects and the one benefiting from them. Just as it would be consistent for these benefits to be included in the entity’s general accounting balance sheet. However, such territorial alignment is more complex: the value of such benefits can only be recorded in cost accounting; it cannot be recorded in the general accounts.

Managers and accountants do not understand the notion of materiality in the same way. The distinction between the two points of view is based on the definition of the concept of an asset. This refers to items from which the entity can confidently expect future economic benefit.

From the accountant’s point of view, one can expect a future profit from what one legally owns. When an asset is considered immaterial, i.e. when it does not have “materiality” from the accountant’s point of view, it is because the company does not own it6. The material or immaterial nature of an asset should not be confused with whether or not it has a physical substance (Fustec et al. 2011, p. 38). Physically “immaterial” assets, such as patents and trademarks, can be recognized in the balance sheet because they are “material” within the meaning of accounting standards, which, because of the control that their ownership establishes, recognize the benefits they confer.

From the manager’s point of view, however, it is possible to expect a future economic benefit from an element that you do not have. The condition, however, is to have control over it. A company controls an immaterial asset “either because it owns it and can act on it, or because it disposes of it and can act on it to obtain a future profit” (Fustec et al. 2011, p. 38). It is this expectation of future profit that legitimizes the work by which financial analysts structure immaterial capital into different categories of immaterial assets, even though these assets cannot be included in the accounting balance sheet.

Immaterial assets therefore reflect the “invisible value” of the company, a value that market experts may be able to recognize, up to the level of goodwill, in the event of a future merger, acquisition or various approaches to access financial capital.

Figure 2.6. Immaterial capital and accounting balance sheet. Adapted from (Fustec et al. 2011, p. 38)

The consideration of intangible capital, which pushes analysts to represent inter-entity interactions and is therefore a major step forward compared to the internalization of externalities, remains limited.

This conflict of representation of what is worth and what is important, between an accountant and a manager of an entity, is just as problematic at the level of the territory in which it is part. The representations that cross paths without meeting are then those of the national accountant and the politician.

The case of social economy is symptomatic. As soon as an attempt is made to broaden the understanding of productive phenomena beyond the entity’s capital and its use of paid employment, accounting does not allow the measurement of wealth (as defined in the first chapter) to be taken.

In France, figures published by INSEE since 2005 show a gap between the employment rate in the social economy and the share of GDP associated with this employment7. According to Kaminski (2009), the way GDP is calculated – based on the wage bill and not on the structure of employment – and the relationship between social economy and the notion of capital contribute jointly to this gap.

Concerning the structure of employment, Bisault (2011) notes the gap between data processing infrastructures and the specificities of value added (VA) recording processes. The CLAP (Connaissance locale de l’appareil productif – Local Knowledge of the Productive System)8 system does not take into account part-time employment, which increases the gap between employment in social economy and the weight of the associated VA in the calculation of GDP.

Concerning the ratio to capital, Kaminski (2009) points out some factors that reduce the contribution of social economy to GDP. In particular, it notes the low correlation between employment and the need for fixed assets, the absence of a need for a surplus for shareholders, and the low rate of market activity in social economy (less than 20%), and therefore of the VAT generated.

Ecological economics also faces problems of the structure of employment and the relationship to capital. As discussed in Chapter 1, ecosystem functions provide biophysical work that provides services to the economy and society.

In recognition of the limitations of the analogy, it can be argued that the human economy “employs” ecosystems whose emerging properties are considered as services. What is part of the biophysical work necessary to provide a valuable ecosystem service is currently not taken into account by the economy9. We are faced with a problem of the “structure of employment” of ecosystem entities and functions.

Limiting the consideration of productive work by excluding how ecosystems are used (“employed”) to consider only the service they provide explodes the relationship between the valuation of physical assets by industrial entities and the valuation of natural capital. Consequently, on the one hand, because of the conception of natural capital resulting from this representation deficit, the contribution of the environment to GDP is considerably reduced, and, on the other hand, what is even more serious, this profound lack of knowledge of the ecosystem dimension of the productive system prevents serious consideration of its maintenance and preservation.

2.2. Reinventing performance

What ecological economics and social economy have in common is that they address the systemic aspects of the wealth production process as a matter of priority. They improve the understanding of productive phenomena through the recognition of the ecosystem and social – community – components of work. The economist and the manager will then have to transform their representations of the territorial anchorage of the industrial organization to enhance these new forms of work.

In a social and ecological economy of sustainable development, linkages, whether between individuals and communities or between physical elements and ecosystem functions, precede the economic good. These links are necessarily understood at the scale of a territory, which is not very compatible with the attribution of a VA to the activity of a single institutional entity. Current economic and accounting practices – internalization of externalities and valuation of intangible capital – are too imperfect a response to this inadequacy. The economy of sustainable development cannot therefore be limited to their rearticulation.

The principle of distinction–conjunction (Morin 1990) makes it possible to explain the interest of a joint, but differentiated approach to what concerns the collective representation of the value of interactions between entities at the territorial level, and of accounting valuation at the entity level. It helps to mobilize the concepts of PSS and functional ecosystem.

A shared representation of the interests to support a multifunctional production, and an accounting representation by the organization that owns the means of this production, are based on different logics (distinction). Nevertheless, the complementarities, concurrences, even antagonisms between these logics must be addressed in the same unit of analysis, without their differences being erased by this unit (conjunction).

The evaluation of an organization’s performance, in order to understand what determines the evolution of that organization, must be adapted to this principle.

2.2.1. Information socioeconomy

2.2.1.1. Functionality and productivity

For Djellal and Gallouj (2012, p. 24), the notion of performance refers to “the ability of an organization (or any other analytical entity) to achieve a number of general objectives, set a priori, concerning various aspects of its development. It covers (or can cover) multiple objectives, not only economic, but also social, ethical, ecological, etc.”

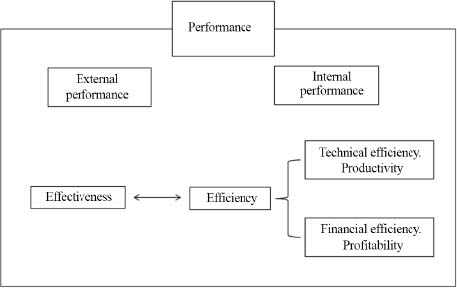

Djellal and Gallouj distinguish between effectiveness and efficiency. Efficiency (external performance) reflects the degree to which objectives are achieved, whatever they may be, without regard to the costs incurred or the volumes created. Efficiency (internal performance), on the other hand, reflects the extent to which these objectives have been achieved by saving resources. They consider this efficiency from two complementary perspectives: financial and technical.

Figure 2.7. Productivity, efficiency, effectiveness, performance (Djellal and Gallouj 2012)

The functional economy paradigm overturns this understanding of the relationship between external and internal performance. In a functional ecosystem, organizations are structurally independent from the point of view of financial accounting, but functionally linked from the point of view of the management and valuation process of PSS (see section 2.1.1.2). This involves redefining the scope of analysis of the relationship between profitability and productivity, i.e. the scope of analysis of efficiency.

Addressed in a functional economy, efficiency analysis necessarily goes beyond the boundaries of the organization. Efficiency is the ability of an organization to collectively represent itself as a functional phenomenon that it recognizes as positive, concrete and meaningful. It is also due to the fact that this recognition leads to support for activities that promote the existence of this phenomenon. This support may include PSS contracts to endorse the recognition of the functional benefits in question, and to contract for services to access these benefits.

Associating efficiency with internal performance is no longer entirely consistent. And qualifying the organization’s effectiveness, i.e. the achievement of its objectives, as external performance also loses meaning. In a functional economy, the effectiveness of the organization is inseparable from the determinants of its efficiency. If the efficiency objectives of the organization are achieved and if other actors combine this with a reinforcement of the conditions of existence of functionalities that are useful to them, the organization can benefit from the contractual support of these actors.

Moreover, when we talk about the technical component of efficiency – also called productivity – the technical term is too often strictly associated with the physical dimension of the productive apparatus. The activation of a capacity for collective but differentiated representation of the “materiality” of a functional phenomenon, which induces the possibility of a service contract, nevertheless implies a socioeconomic technique.

Therefore, why not consider a technical service-based efficiency – or service-based productivity – attached in particular to the collective mobilization of a PSS supply production technique?

We will distinguish this service-based technique, purely focused on the recognition of produced utilities and the negotiation of the conditions of their availability, and therefore on the act of contractualization, from another type of technique: a contributory technique.

In past innovation processes, the actors of the functional ecosystem have mobilized and generated together information and knowledge that enable them to perceive the interest they have, each and everyone, in getting involved in PSS. If the service-based technique allows the bi- or multilateral recognition of the usefulness of an activity at the time of a contract, the contributory technique allows the collective recognition of the function of this activity, over the time of its territorial inscription.

We will therefore also consider a functional technical efficiency – or functional productivity – attached to the production and mobilization of the information and knowledge necessary to build a functional ecosystem.

The notion of productivity of an organization then refers to both the technical efficiency of service, the technical functional efficiency and the technical efficiency of working with natural resources through the use of physical technical objects. In short, the analysis of technical efficiency – understood in the sense of industrial economy – would exist only as a component of the analysis of technical efficiency considered by territorial economic information. And it is this set of analytical components brought together by the notion of technical efficiency – or productivity – that is to be compared with financial efficiency.

Considering productivity as an ability to save resources when achieving objectives (Djellal and Gallouj 2012) therefore implies specifying which types of resources should be available for the functional economy. This also implies clarifying what is generally understood by “saving” resources qualified with regard to quantities that cannot be compared and of which dynamics of specific evolutions are apprehended by measurement methods with incommensurable units.

2.2.1.2. What saving means

Some resources are consumed and degraded during wealth production processes. This is the case for energy and material resources. In this case, “saving” means either reducing the intensity of activity, increasing the level of physical productivity, or combining both approaches. Other resources are not consumed and degraded, but mobilized and strengthened. This is particularly the case for information, knowledge and shared knowledge heritage resulting from the experience accumulated during the mobilization of past service-oriented and functional techniques.

In this sense, we have proposed the notion of functional heritage (Morlat 2016). This heritage can be mobilized while being preserved (saved) if the conditions for the preservation of knowledge and shared knowledge heritage through the structuring of information in a network are met. But it can also be dissipated by its mobilization. This is the case if the efficiency analysis only integrates the relationship between physical technical efficiency and financial efficiency, omitting the importance of functional and service-oriented techniques.

Let us take the example of the design of an infrastructure project by the actors of a territory. The monetary representation of costs and benefits is only one part of economic reflection, which itself is only one of the dimensions of the evaluation of the functions degraded or reinforced by the territorial inscription of the project and the variations in utilities removed by each. This evaluation involves information and knowledge by which stakeholders base their expression of interest in the project by constructing its ecological, social and economic significance, i.e. by constructing the meaning that the project can have. Not in the absolute, but from the perspective of the functional ecosystem.

When this infrastructure project is contracted out, the polarization between monetary and non-monetary information is reversed. Possible social and ecological criteria are associated with the descriptive non-monetary economic criteria for the implementation of the project, and all these criteria are incorporated into the clauses of the contract, which as a whole is associated with a monetary price.

Then, at the time of the accounting valuation – which can be considered as a third “moment” of the territorial economic information cycle – one part of the non-monetary information is included in the notes to the entities’ accounts, one part is included in non-financial reporting and another part in public statistics. The media for representing non-monetary information are thus separated from the media for representing monetary information.

The reversal of monetary/non-monetary polarity, and then the separation between these two types of representation, dissipates economic information. It prevents the analyst from comparing the monetary exchange values associated with each of the actors with different utilities of a project, and the non-monetary use and non-use value of functions whose quality is normalized or degraded by the territorial anchorage of this project.

A perpetuation of this reversal of polarity, and of the separation between monetary and non-monetary information, leads to a dissipative cycle of territorial economic information and of the ability to interpret the relationships between functions and utilities, i.e. to represent functionalities.

Yet, precisely, the challenge for the sustainable development economy is, as we mentioned in the first chapter, to limit the dissipation of information on the co-evolution of social, ecological and economic systems. It is a question of opposing this dissipation of information with a territorial process adapted to its conservation.

Figure 2.8. Dissipative cycle of economic information. Adapted from Morlat (2016)

The action of valuing a service at the level of an entity is indivisible from a collective action of social construction of the functional significance of productive phenomena, therefore from an action of valuing, at the level of the territory. This valuation is therefore a process that must be considered separately and jointly at the micro- and mesolevels, and during which the structure of monetary and non-monetary representations of information evolves.

The requirement of absolute decoupling as a valuation criterion implies that this evolution of the structuring of monetary and non-monetary representations of economic information is based on biophysical, non-monetary information.

The functional economy makes it possible to build an appropriate valuation system. In this economy, the physical good is considered as an asset and no longer as a consumable (Lauriol 2008). The physical dimension of the productive apparatus, i.e. the industrial economy, becomes a support function for wealth creation – in the sense that we have defined this wealth in the first chapter. It is a paradigm shift: most productivity is determined by the availability of a potential of functional phenomena that are qualified as – functional when an actor recognizes their usefulness. And most of the profitability is determined by the ability to award a price to these utilities as part of a service contract.

This processing of information for valuation, a cyclical process – monetary and non-monetary – a trans-scalar process – i.e. one that transcends the scales of analysis – and bounded by an absolute biophysical limit, cannot be dissociated from an understanding of the information production process.

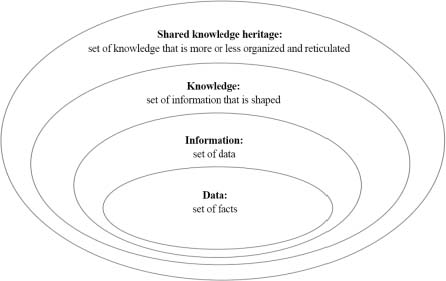

Information can be considered as a contextually attributed meaning to a set of data, such as social, ecological and economic facts. In this respect, we distinguish between the scale of analysis and the level of analysis: the scale refers to the facts, the level to the issues considered by the actor who objectifies these facts.

According to Laperche (2018),knowledge, built or mobilized by an actor who carries out the action of acknowledging facts, and their implications with regard to a certain number of issues, can be considered as a set of information put into form. Knowledge is then what the actor uses to interpret the facts in order to produce data, and what he/she uses to select these data in order to constitute them into a meaningful set, i.e. information.

Pesqueux (2018) proposes a fairly similar gradation between data, information and knowledge; he inserts between the latter two the notion of skills10, i.e. capacity.

The central question in economics – an issue whose criticality is more acute when dealing with the sustainability of development – is that of the adequacy of the knowledge mobilized for a specific value recognition process. For example, our critique of neoclassical practices is based more on the relevance of knowledge, often mobilized in the same way for very disparate evaluation situations, than on the intrinsic quality of this knowledge. This practice leads to considering only some of the economic facts worthy of recognition: neoclassicals produce data intended to be arranged into information that will only make sense in a logic of serviceoriented productivity.

It is therefore necessary to intervene directly at the foundation of the knowledge production process, i.e. at the foundations of shared knowledge heritage.

Figure 2.9. Knowledge: a Russian doll (adapted from Laperche 2018)

We will refer, in addition to the representation proposed by Laperche (Figure 2.9), to the concept of transindividuation introduced by Stiegler (see section 1.2.2.2), which is based on a dynamic approach and therefore adapted to the joint reading of the information creation process and the valuation process.

Supporting the creation of shared knowledge heritage can lead actors with varied rationalities, and diverging views on issues they address at different times, to produce common reference systems that can generate detailed agreements on the impact of facts, i.e. on the value of productive phenomena.

Without access to shared knowledge heritage, and therefore without the capacity to mobilize appropriate knowledge, the negotiation that underpins the value recognition of productive phenomena can only lead to the capture of information and thus to the inability to take both an individual and a collective look at the facts.

2.2.2. Preserving the functional heritage

2.2.2.1. Three levels of decoupling

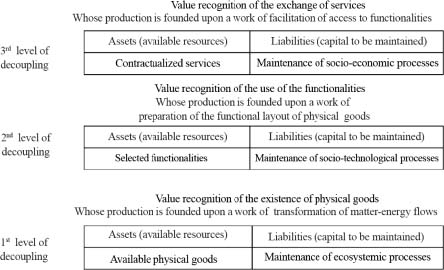

Considering the physical good as an asset renews the field of what is worth and what matters. Through this principle of capital asset, the functional economy structures a new accounting representation space.

The valuation of the physical asset, as an asset of the entities that own the industrial production units, is carried out with regard to what is essential for these entities to be able to dispose of it and use it. It is then primarily natural capital that should be recorded as a liability for each of them. We therefore suggest that a first level of decoupling be included in the accounts of the entities in the territory, in line with the technical and economic direction of this decoupling.

The functionalities, i.e. the utilities recognized for functional arrangements of physical goods, are to be transcribed by another line of assets, which are not to be valued solely in terms of natural capital. It is indeed here the quality of the territorial sociotechnical organization that is crucial, in that it provides the basis for a capacity for communication between industrial production units and the actors in the territory who perceive the effects of these productions and are therefore likely to recognize and qualify their multiple functions. A second level of decoupling would thus be reflected in the entities’ accounts, corresponding to the meeting point between the technical-economic and socioeconomic paths of decoupling.

The valuation of assets specific to this second level of decoupling no longer concerns only the owners of industrial production units. Each entity whose activity benefits from the advantage of multifunctional production can legitimately include in its assets – material or immaterial – a functionality that reflects this advantage. However, the condition of rigor would be that it then jointly values, on the liabilities side, the socio-technical relations capital that underpin the existence and recognition of this multifunctional production.

In other words, the registration of physical assets by some entities in the territory could be carried out in a coordinated manner with the registration of intangible assets (material or immaterial) by others. All these entities would together have the responsibility for natural and socio-technical capital, whose collective and then differentiated valuation would imply jointly defined rules, and particular attention to the distinction between the level and scale of decoupling analysis. Such an approach would initiate the institutional recognition, through accounting, of a territorial functional ecosystem.

At a third level of valuation, after those of physical goods and functionalities, comes the valuation of service contracts based on these functionalities. These contracts give rise to the formation of financial and non-financial assets by a set of entities that does not exactly overlap with and go beyond that of the entities benefiting from multifunctional production. The involvement in the contractualization of a service based on functionality can indeed confer specific advantages on financial sector actors. For these actors, it is contractualization that constitutes the function associated with use value, in that it is likely to form the basis of financial services.

It is at the interface between this third level of decoupling and the two previous ones that the need to rethink financial work must be addressed.

Figure 2.10. Three levels of decoupling to be shown in the accounts of the entities that make up a territorial functional ecosystem

2.2.2.2. An intangible and indivisible shared good

To go even further in controlling the sustainable availability of assets within and beyond the perimeter of ownership of the means of production (i.e. in securing liabilities), the organizations of a territory must coordinate themselves.

Liabilities will only be properly valued and capital maintained and renewed on a long-term basis following negotiations on contributions to multifunctional production. A framework must be established to enable each one to clearly and jointly recognize the value of the utilities of these productions, and to manage the collective process of managing contributions to their sustainability.

For Barthélemy et al. (2003), the analysis of multifunctional productions leads to “discussing the use and extension of the notions of capital and externality and then studying a possible alternative that requires recognizing heritage, not as an equivalent or support of capital, but as a category carried by a logic heteronomous to market logic. The basis of heritage lies in the need for the persistence or reproduction of an element considered fundamental to the life of the group and essential to its perpetuation”11.

After the extension of the relationship to capital suggested in the previous point through the proposal of three levels of decoupling and their systemic implementation, let us now clarify our relationship to the use of the notion of externality.

According to Zacklad (2007), “the consideration of positive externalities, which in our view must be a defining characteristic of the functional economy, implies constituting them as an indivisible shared good that often encroaches on the common goods of a sociological, legal or territorial community”12. Zacklad brings this notion of indivisible shared good closer to that of “immaterial collective heritage” proposed by du Tertre (2006).

The specific characteristic of the functional economy is to pursue an objective of decoupling through a path of territorial socioeconomic innovation involving a both distinct and joint approach in the intra- and transentity analysis of the value creation process. This is the precaution Zacklad (2007) takes when he discusses the need to constitute externalities as an indivisible shared good.

However, this turn of phrase leads to confusion of genres. “Positive externalities” are not, in our view, an object that can be “constituted as a shared good. They are information derived from the analysis of a functional phenomenon whose existence is only addressed by neoclassical knowledge unfit to lead to an understanding of what a shared good is.

This is not yet another “fight in vain” between socioeconomic and neoclassical approaches. The consequences of the neoclassical approach to knowledge mobilization are very practical.

The internalization of information on the value of functional benefits in market prices – in the context of service contracts – fails to capture the value of the knowledge and linkages between actors that underpin innovation processes.

Indeed, even in an ideal theoretical situation of allocating property rights and “perfect” information – thus tolerating two dimensions of reductionism – valuing the external effects of an activity only reflects the utilities that entities are able to recognize. Nowhere in this valuation of externalities is the existence value of the functional ecosystem that allows this recognition considered, so nowhere does the value of the shared good appear.

This heritage and intrinsically territorial value is the basis of the entities’ ability to constitute themselves as functional ecosystems, to recognize the valuable uses of certain functional phenomena and to co-produce the conditions of their existence or persistence. Calling these valuable utilities externalities is therefore a total misinterpretation. These utilities are a collective product resulting from a collective intention and therefore have nothing “external” to the productive phenomenon: they are the expected result as well as the source!

This could remain a point of detail, rhetorical, without too many consequences except those that could be induced by the propagation of representations that run counter to the paradigm that is being promoted. The essence of our disagreement with the proposal to “constitute positive externalities into an indivisible shared good” is that the notion of an indivisible shared good is then taken over and turned into an impoverished and closed container.

Constituting positive externalities into an indivisible shared good could indeed lead to forgetting that the indivisible shared good, or the collective immaterial heritage evoked by du Tertre, or what we call functional heritage, is made only of utilities. This is not the case. The reality of a shared heritage within a functional ecosystem is made up of everything that through social connection allows the recognition and expression of interests to act collectively. This heritage is everything that allows the emergence of utilities, and this whole – this totality – cannot be summed up in the sum of these utilities. It is a shared knowledge heritage.

The same issue is raised by the relationship to intangible capital. Does the sum of the valuation of the immaterial capital of the contributing entities equal the value of the immaterial capital of the functional ecosystem? No.

Something else is needed for the actors to advance together the understanding of what is material and what is not. The manager must enter into an approach of co-producing functional phenomena, and the accountant must be able to recognize and measure valuable utilities.

These skills necessary for the coordinated mobilization of specific knowledge can emerge through the production of common knowledge. This is the phenomenon of transindividuation described by Stiegler (2006) (see section 1.2.2.2). And considering value analysis as part of the analysis of this phenomenon implies considering a time standard, that is the time of shared knowledge heritage production.

The functional shared heritage to which we refer reflects the notion of territorial heritage, as understood by Colletis and Pecqueur (2004), and which must integrate, beyond the links, the time dimension, i.e. a historicity.

For them, “‘heritage’ – if we want to use this term to help qualify a territorial construction that would not produce ex-nihilo – is constituted by the memory of previous successful coordination situations, by the trust between the actors that is the result, as well as by specific virtually complementary cognitive resources (likely to be combined to solve future productive problems)” (Colletis and Pecqueur 2004).

2.3. Conclusion

What differentiates a PSS from a service market is above all its purpose. When they consider themselves independently of each other, the market entities of a territory pursue an individual goal of profit. They are governed by a regulation that – within the same sector – applies to all of them in the same way. However, each must deal with local singularities that are specific to it and that specifically influence its performance.

Subordinating the logic of the industrial sector to that of the functional ecosystem encourages the emergence of territorialized cooperation strategies that also include non-market players. Market entities then have non-monetary strategic information, built locally, that feeds the decision-making process – thus balancing regulatory and market injunctions. They can therefore undertake with a higher degree of ambition – both in terms of profitability and sustainability of the territory.

The functional, territorial, immaterial, knowledge based, shared heritage – or whatever the qualifiers given to a group’s ability to structure information in a network and then mobilize it in order to collectively produce wealth – underlies individual performance. It is at the origin of this component of productivity that we have described as functional technical efficiency, or functional productivity, and which we believe must be considered as much as service productivity, perhaps more so.

These intangible components – functional and service – of technical efficiency, i.e. the share of productivity that is not due to industrial technical efficiency, respectively, describe how an activity recognizes the existence of the functionalities from which it benefits, and how it values them in the form of services. It is the combination of these two types of efficiency that makes it possible to evaluate medium- and long-term investment.

The recognition of multifunctional productions opens a path that can lead to theoretical and practical coexistence between neoclassical and socioeconomic approaches, as mentioned at the beginning of the chapter.

A condition for this coexistence is that the two components of efficiency are “treated” in a balanced way. For this to be the case, the practices of internalizing externalities and valuing immaterial capital at the entity level must not reduce the collective capacity to represent territorial functions and their utilities. Another condition is that entities can individually and reliably evaluate and value the benefits of collectively supported multifunctional productions.

Anchoring financial valuation in this complex locality, in which an activity must be conceived both as a process undertaken by an entity and as part of a territorial organization, implies a renewal of the economic information system. We are not just talking about accounting practices here. More broadly, the challenge is to enable an entity to seek and produce information that helps it to identify and publicize the productive phenomena on which it bases the accounting valuation of the service contracts it proposes or on which it depends.

In other words, it is a matter of working toward the institutional embodiment of the functional ecosystem through the deployment of a territorial information system.

- 1 Eco-industrial strategies (Erkman 1997) are mainly based on the dissemination of the logic of ecological economics in the territorial design of the physical anchoring of production patterns. The idea is to consider the organization of the physical dimension of productive systems as an industrial ecosystem (Boons et al. 2000), and to study the metabolism of this ecosystem in order to better understand its interface with natural environments. This industrial metabolism refers to “the whole of the materials and energy flows going through the industrial system. It is studied through an essentially analytical and descriptive approach (basically an application of materials-balance principle), aimed at understanding the circulation of materials and energy flows linked to human activities, from their initial extraction to their inevitable reintegration, sooner or later, into the biogeochemical cycles” (Erkman 1997).

- 2 The stakeholder approach is based on five principles: the principle of stakeholder cooperation; the principle of stakeholder responsibility, the principle of complexity; the principle of continuous creation; and the principle of the emergent competition (Freeman and Phillips 2002). These principles propose a liberal and ethical approach to capitalism based on interactions between actors – considered as key to optimizing local economic governance. If the industrial economy is a diffusion of the logic of ecological economics to industrial production, the stakeholders’ approach is, in our opinion, to a certain extent, a diffusion of the logic of social economy in the territorial conception of the institutional and organizational anchoring of productive schemes.

- 3 The term “monetary” is intended to make it clear that there are other forms of poverty, in particular administrative poverty resulting from the distance from public services and which may lead to situations of precariousness.

- 4 Agence française de l’environnement et de la maîtrise de l’énergie.

- 5 Source ademe.fr. Available at: https://www.ademe.fr/dossier/aides-lademe/mode-demploi-aides-lademe, accessed on 10/23/2018.

- 6 What is material, on the assets side of the balance sheet “is composed of fixed assets (intangible, tangible and financial assets) and current assets (inventories, receivables, financial investments and cash)” Source Vernimmen.net. Last accessed on 01/17/2016 at: http://www.vernimmen.net/Vernimmen/Resumes_of_chapters/Part_1_The_financial_diagnosis/Chapter_4_L_economic_asset_and_financial_resources.html.

- 7 In 2010, social economy accounted for around 6% of the gross VA created in France (Roucher 2013), while in the same year, the weight of its salaried workforce in the economy as a whole was 10.3%.

- 8 Available at: https://www.insee.fr/fr/information/2044773, accessed on 07/29/2018.

- 9 The notion of a production frontier proposed by Eurostat speaks for itself: “Production is an activity carried out under the control, responsibility and management of an institutional unit that uses inputs of labor, capital and goods and services to produce outputs of goods and services. Production does not cover natural processes which have no human involvement or direction, such as the unmanaged growth of fish stocks in international waters, but production does include fish farming” (Eurostat 2013, point 3.07).

- 10 “If ‘data’ and ‘information’ are clearly within the information systems theme, ‘skills’ adds the human resources dimension and ‘strategy’ and ‘knowledge’ the ‘strategic’ dimension. Thus, the notion of data refers to the figure of the engineer, that of information to that of the journalist, that of competence to that of the manager and that of knowledge to the scientist” (Pesqueux 2018).

- 11 Barthélemy et al. (2003) thus draw within the “Groupe de Reims” the foundation of the current of the patrimonial economy, from which emanates the notion of multifunctional object that we have mobilized to introduce the functional economy.

- 12 The common goods to which Zacklad refers (2007) “most often associate ecological (air, water, soil, etc.), human (health, culture, language, security, wellbeing, etc.) or productive dimensions in the restricted sense (transport infrastructure, energy production resources, free software, documentary heritage, etc.)”.