Chapter 9

Conclusion: New Directions for the CIO of the Future

This book has explored many conceptual aspects of the CIO position and how the role can help firms compete in a rapidly changing world. Case studies were presented to show why certain CIOs have achieved success with their firms. It is most important, however, for us to represent the apparent skills that are common among successful CIOs that appear to work in almost any organization. Hence, there can be no boilerplate methodology for the process of how to be successful with technology; rather it is a way of thinking and an ability to be strategic. Our research showed that there are 23 common attributes that CIOs must have for them to evolve the role in their firms. These attribute are more behavioral from an individual perspective, and philosophical from an organizational point of view.

In Langer's study of CEO perceptions of IT, he found that the role of IT was not generally understood in most of the organizations he surveyed, especially at the CEO level.1 Little has changed according to the discussions and research we have had over the past year of writing this book. There appears to still be inconsistent reporting structures within the IT organization, and there is a fair amount of frustration of CIOs as effective “technology” strategists and as fiscally responsive members of their executive teams. Furthermore, there are still many non-IT executives who are not satisfied with IT performance, and while most agree that technology should play a larger role in marketing, few have been able to accomplish this. The general dilemma has still involved the inability of the CIO to integrate technology effectively into the workplace. Certainly, a principal target of this book is to answer the question of what CIOs need to do and in what directions their roles need to evolve regarding the firm as a whole. Other concerns center on general organizational issues surrounding who IT people are, where they report, and how they should be evaluated. CIOs must also provide better leadership with respect to guiding a company through the challenges of unproven technologies. While technology behaves dynamically, we still need processes that can validate its applicability to the organization using sound business processes. Another way of viewing this dilemma is to accept the idea that certain technologies need to be rejected because of their inappropriateness to drive strategy.

The CIO function is somewhat unique in that it is often viewed from a project perspective; for instance, that which is required to deliver technology, along with the cultural impact it has on the organization, tend to be measured by project deliverables, due to the pressure to see measurable outcomes. From a project perspective CIOs can be seen as executive project managers, which requires them to communicate with multiple business units and management layers. They need to establish shorter project life cycles and respond to sudden changes to business requirements. No longer does a traditional project life cycle with static dates and deliverables work for today's fast-paced businesses. Rather these projects are living and breathing entities that must be in balance with what is occurring in the business at all times. Most important is that project measurable outcomes must be defined and in balance with expected organizational strategic goals.

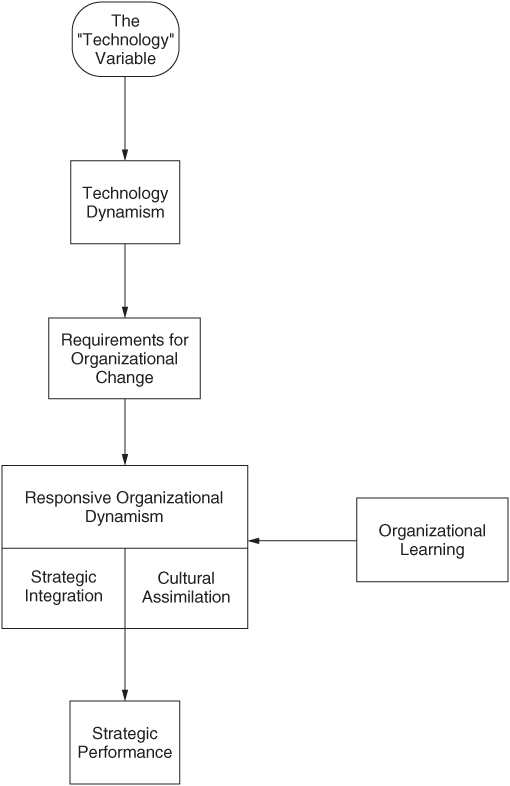

Key to our philosophy is Langer's definition of the role of technology as a dynamic variable, which he termed technological dynamism. Responsive organizational dynamism (ROD) represents Langer's attempt to think through a range of responses to the problems posed by technological dynamism, which is an environment of dynamic and unpredictable change resulting from the advent of innovative technologies.2 This change can no longer be managed by a group of executives or managers; it is simply too complex, affecting every component of a business. A unilateral approach does not work; the problem requires a cultural transformation that we believe can be accomplished only by a technology executive. The question, then, for CIOs of the future is how they can create organizations that can respond to the variability of technologies in such a way that its responses become part of its everyday language and discourse of the firm. Not an easy task, yet this technological state of affairs is urgent for two major reasons. First, technology is not only an accelerator of change, it requires accelerated business responses. Organizations can no longer wait for a committee to be formed or long bureaucratic processes to make decisions on how technology will be adapted. Second, the market is unforgiving when it comes to missing business opportunities. Every missed opportunity for not responding in a timely fashion can cost an organization its livelihood and future. As stated by Johnson, Saveri, and Schmid:

The global marketplace requires constant product innovation, quick delivery to market, and a large number of choices for the consumer, all of which are forcing us to rethink the way we structure our business organizations to compete. Indeed, many businesses are finding their traditional structure cumbersome—the way they work is more of an obstacle than help in taking advantage of global opportunities.3

While ROD is the overarching approach for a firm that can perform in a dynamic and unpredictable environment, there are two major components to that approach that we raise for further consideration. Langer discussed how technology, as a variable is unique in that it affects two areas of any organization. The first is the technology itself and how it operates with business strategy. He called this the strategic integration component of ROD. The challenge here is to have organizations create processes that can formally and informally determine the benefit of new and emerging technologies on an ongoing basis. The second component is cultural assimilation, which is about managing the cultural and structural changes that are required when new strategies are adopted by the organization.

Creating an environment of ROD needs processes that can foster individual and organizational business integration of IT. The 24 techniques that were advocated by our case studies best fit the need, as they contain the core capabilities to assist organizations in reinventing themselves as necessary, and to build an organization that can evolve with technology, as opposed to one that needs to be reorganized. We have presented many strategic advocacy concepts and modified them to provide specific remedies to the challenges required to create ROD firms. We have also presented the complex issues of working with politics and understanding degrees of separation so that CIOs can use them in a way that can help them with their C-suite colleagues and other key leaders in business units. Indeed, understanding how to maneuver through complex organizational structures and people was clearly an advantage for the successful CIOs in our research. Our study of how strategic advocacy is fundamental for CIO success consists of eight key conclusions:

We believe that Langer's maturity arcs provides the necessary framework for the development of the future technology executive as described earlier. The use of these arcs can measure where individuals and organizations are in their trajectory toward the integration of emerging technologies in their business strategies. These maturity arcs also provide a basis for how to measure where the organization is, what types of corrections are necessary to consider, and what outcomes to expect. Indeed, providing measurable outcomes in the form of strategic performance is the very reason CIOs should consider embracing this model.

We also discussed a number of methods to manage technology business integration, by modifying theories of knowledge management and change management so that they specifically addressed the unique aspects of change brought about by new technologies. We looked at how the CEO needs to become more knowledgeable in technology, and based on case studies and research, Langer provided sets of “best practices” to suggest that staff members cannot become part of a technology-based organization without the participation of the CEO and his or her executive committees. Langer formulated best practices for three major organizational structures along with corresponding maturity arcs to lay the foundation of what each community needs to do in order to properly participate in the transformations indicated for ROD. To this end, Langer proposes a road map that, if followed, could provide the mechanisms that lead to the kind of organizational transformation that is empowered to handle the challenges of new technologies. This process is summarized in Figure 9.1.

Figure 9.1 Responsive Organizational Dynamism Road Map

A theme of this book is the recognition of the importance of understanding the process of evolution. In the past, information traveled much slower and there was more time to interpret its impact on the organization. Today, the wait is shrinking and therefore evolution can and should occur at a quicker pace. Indeed, organizational evolution is intertwined with the dynamics of community legitimization.4 Technological development for a particular population has widespread consequences for the rest of the organization. In these cases, technological innovations represent a form of collective learning that is different from direct learning from experience alone.5 There are many of us who believe that effective management must be implemented through top-down approaches. Many such efforts to reorganize or reengineer organizations have had disappointing results. Many of these failures, we believe, are attributable to a dependence on management intervention as opposed to Langer's strategic integration and cultural assimilation components of ROD. Technology only serves to expose problems that have existed in organizations for decades: the inability to drive down responsibilities to the operational levels of the organization. Through automation advances, CIOs have a unique opportunity to truly address this dilemma.

Our case study interviews provide a pragmatic view toward the attainment of CIO excellence, assuming the correct support for the role in the firm exists. We advocated that CIOs must “redefine” their role and build toward a “natural evolution.” However, we also admit that there needs to be some level of strategic support from the CEO for the position's potential to be realized in the business. Our case studies reflect that progress toward CIO support may be a gradual one. As such, we determined that organizational transformation must be addressed along the same basis—that is, transformation is a gradual process as opposed to a planned event with a specific outcome. We believe that organizations should look at IT business integration in much shorter “chunks,” as opposed to an immediate “big bang” approach, which rarely work and are difficult to measure. Our suggestion to better measure IT integration was through Langer's Balanced Scorecard, which provides a more evolutionary approach to success.

Another important concept in this book is the reconciliation between control and empowerment. As organizations find that their traditional structures are cumbersome when dealing with emerging technologies, they realize the need to empower IT and non-IT employees to do more dynamically. With this empowerment, employees may make more mistakes or seem less genuine at times. When this occurs there may be a need for management controls to be instituted and power-centralized management styles to be incorporated. Unfortunately, too many controls end any hope of sustaining a creative organization that can foster the dynamic planning and needs of ROD. It also blocks the molding of true integration with the business, which requires common threads of discourse and language. Indeed, it is CIO discourse that lays the foundations for addressing the dilemma of control versus empowerment.

We are really beginning to experience the results of emerging technologies, particularly in global companies. We have seen a continual trend where offshore product development and maintenance continues to be at an all-time high and local employment down. The advent of this cycle lays a foundation for the new trends of the global worker operations, many of which are shifting from a labor-intensive process to needs for thinking, planning, and management. It is a perfect example of N = 1 and R = G so eloquently presented by Prahalad and Krishnan. However, we do see a recent movement to balance outsourcing with local resources. The challenge for CIOs is to find more ways to create pipelines of skilled workers, not only internationally, but also in local communities. Indeed, Randy Mott, CIO of General Motors, recently announced his plans to bring back 90 percent of its IT outsourcing abroad. We also see that the way individuals communicate or the rules of their engagement are quickly changing, particularly in the need to create more research and development (R&D) infrastructures that can respond quicker to innovation opportunities brought about by emerging technologies. We saw very clearly through our case studies that business strategy and technology are major investments and the acknowledgment by CIO leaders that IT was more about business than technology.

To address the lack of understanding of the technology life cycle, we presented Langer's concept of driver and supporter functions and mapped them to evolutionary business transformation. This life cycle is one that ties business strategy into technology and should be used to convey ROD to executives. Driver functions explain why strategic integration is so important and present a case that requires more marketing-based philosophies when investing in technologies. This means that early adaptation of technology requires, as Bradley and Nolan coined, sense and respond approaches, where IT organizations can experiment with business units on how a particular technology may benefit the business.6 Siemens provided a good example of different ways of creating infrastructures that can support technology exploration, including Deasy's 90-day program there, where technology investments were reviewed periodically to see what adjustments are required to maximize the investment. It also provided a way to cancel those investments that were not paying off as originally forecasted. Understanding that changes along the way are needed or that there are technologies that do not provide the intended benefits must become a formal part of the process, and one that CEOs must recognize and fund. However, the supporter role is one that addresses the operational side of IT, such that executives and managers understand the difference. We treat the concept of supporter as an eventual reality—the reality that all technologies once adapted by operations must inevitably become a commodity. This realization paves the way to understanding when and how technologies can be considered for outsourcing based on economies of scale. The adaptation of this philosophy creates a structured way for CIOs to understand the cost side of the IT dilemma, and why it requires business units to integrate their own plans with those offered by emerging technologies. The supporter aspect of technology became the base of cultural assimilation because once a technology is adapted by operations, there must be a corresponding process that fosters its impact on organizational structures and cultural behaviors. It also provides the short- and long-term expected transformations, which ultimately link technology and strategic performance. The driver/supporter philosophy also shows the complexity of the many definitions of technology and that executives should not attempt to oversimplify it. Simply put, technology must be discussed in different ways, and CIOs need to rise to the occasion to take a leadership role in conveying this to executives, managers, and operations personnel. Organizations that can implement driver/supporter methods will inevitably be better positioned to understand why they need to invest in certain technologies and technology-based projects.

These general themes just discussed can be formulated as a marriage between business strategy and technological innovation and can be represented as follows:

- CIOs must change the business cycles of technology investment; technology investments must become part of the everyday or normative processes, as opposed to specific cycles based on economic opportunities or shortfalls. Emerging technologies tend to be implemented based on “stop and goes,” or breakthroughs followed by discontinuities.7

- The previous experiences that organizations have had with technology are not a good indicator for its future use. Technology innovations must evolve through infrastructure, learning, and process evaluation.

- Technology is central to competitive strategy. CIOs need to ensure that technology opportunities are integrated with all discussions on business strategy.

- Managing technology innovations must be accomplished through linkages. Thus, CIOs must establish interfaces across the businesses by being very active with these units.

- Managing intellectual capital is of growing importance. Managing this knowledge requires CIOs of the future to create processes that transfer tacit knowledge to explicit knowledge.

- There are multiple and complex levels of management that needs to be involved in ROD. Successful CIOs must develop architectures, manage change, and deal with short- and long-term projects simultaneously. CIO leadership will understand that there are three primary levels (executive, middle management, and operations) in the business that constitute the infrastructure that best sustains the natural migration toward ROD.

This book looked at business strategy from yet another perspective, beyond its relationship with information technologies. Because business integration is required to foster ROD, strategy must also be linked to other types of technologies, which we called automations. This expansion of the use of many types of technologies should then be seen as strategic automations, which if implemented helps organizations to continually adapt to the changing business environment, including changes brought about by all types of automation possibilities. However, due to the radical speed, complexity, and uncertainty, traditional ways of implementing strategy no longer ignore the nontraditional behaviors of technology. The old methods of determining business strategy were based on standard models that were linear and “plug-in.” As stated earlier, they were also very much based on projects that attempted to design one-time efforts with a corresponding result. As Pietersen explains, “these processes usually produce operating plans and budgets rather than insights and strategic breakthroughs.”8 Technological dynamism has accelerated the need to replace these old traditions, and we have emphasized that organizations that practice ROD must:

- Evaluate and implement technology automations in an ongoing process and embed it as part of normal practices. This requires a change in business integration and culture.

- Comprehend that the process of ROD is not about planning; it is about adaptation and strategic innovation.

- The process must feed on the creation of new knowledge through business integration that leads to strategic organizational transformation.

Many scholars might correlate strategic success with leadership. While leadership, in itself, is an invaluable variable, it is just that. To attain ongoing evolution, we believe we need to move away from relying on individual leadership efforts and move toward an infrastructure that has fewer leaders and more normative behavior that can support and sustain ROD. Certainly, this fosters the important roles and responsibilities of CEOs, managers, and boards; but to have an ongoing process that changes the thinking and the operational fundamentals of the way the organization functions is more important and more valuable than individual leadership. That is why we raised the issues of discourse and language, as well as self-development as an important part of the future success of CIOs. Therefore, the CIO's ability to transform the business community is what will bring forth long-term strategic performance of any firm. However, the transformation must be expanded to include all types of automations for both drivers and supporter functions.

What this book really commits to is the importance of change management—the simple concept that people in organizations need to continually challenge their cultural norms if they are to develop what Mezirow calls “new meaning perspectives.”9 It is these new meaning perspectives that lay the foundation for ROD, so that managers and staff can continually challenge themselves to determine if they are making the best strategic decisions. Furthermore, it prepares individuals to deal with uncertainty as well as the ongoing transitions in the way they do their jobs. It is this very process that ultimately fosters success with dealing with the disruptions of new automation possibilities.

While on-the-job training is valuable, movement or rotations of IT personnel at work has merit for supporting real business integration. Specifically, the relocation of IT personnel to a business unit can serve to get IT staff more acclimated to business issues. This helps IT staff members to begin to reflect about their own functions and their relationship to the overall mission of the organization. CIOs like Passerini at Procter & Gamble took significant steps to accelerate real integration of IT by permanently integrating them in a non-IT business-specific department. This is why the CIO must be a “champion” who can demonstrate to IT staff that the process of business integration is not just lip service but a path to everyone's success in the department. If CIOs nurture the integration transformation properly, it will allow the business communities to become serious about technology best practices and the business's role in its development.

Although this book might suggest to readers that technology is the basis for the need for ROD, the needs for its existence can be attributed to any variable that requires dynamic change. As such, we suggest that readers begin to think about the next “technology” or variable that can cause the same needs to occur inside organizations. Such accelerations, if we are realistic, are not necessarily limited to technology automations. An example is the continual changes in consumer behavior or the loss of jobs due to corporate downsizing from acquisitions. These nontechnology variables present similar challenges in that organizations must be able to integrate new cultures and “other” business strategies and attempt to form new holistic directions—directions that need to be formed very quickly in order to survive. Indeed, trying to predict how consumers will react can be overwhelming. That is, consumers can also behave in a similar way as technology. The ability to adjust to consumer needs and shifting market segments is certainly not always related to technological change. Our point is that ROD is a concept that should be embraced notwithstanding whether technology seems to have slowed down or not having an effect on a specific industry at a particular moment. Thus, we challenge CIOs or chiefs of automation, as we predict, to develop new strategies that embrace the need to become dynamic throughout all of their operations, and to create continual “reintegrations” of business units that plan for ongoing strategic integration and cultural assimilation.

This book has looked upon the advent of technology then to uncover a dilemma that has existed for some time. Perhaps a more general way of defining what ROD offers is to compare it to another historical concept called “self-generating organizations.” Self-generating organizations are known for their promotion of autonomy with an “underlying organic sense of interdependence.”10 Based on this definition, a self-generating organization is similar to an organism, which evolves over time. This notion is consistent with the evolution of the CIO role because it inherently relates to the inner growth stemming from the organization as opposed to only its executives. The self-generating organization works well with business integration and ROD in the following ways:

- Traditional management control systems do not apply.

- Risks are higher given that staffs are granted a high degree of autonomy and empowerment, which will lead to processes that break with the controlling norms of the business and allow for IT integration.

- Adjustments and new processes from the CIO efforts to integrate will be expected.

- These organizations tend to use political advocacy as a strong vehicle to support network building.

- Traditional hierarchical leadership models do not work because they are organized based on influence as opposed to control.

Self-generating organizations have been met with resistance in the past because managers view that they might be losing control. ROD, led by the CIO, provides a hybrid model that allows for self-generating infrastructures while providing certain levels of control within each business unit. In other words, it's more of a distributed leadership model; local control is maintained at the unit level. For example, ROD embraces the breaking of rules for good reasons; it allows individuals to fail, yet to reflect on the shortfall so that they do not repeat the same errors. Everything we have advocated in this book relating to IT drivers supports the idea of an IT batting average. It also allows employees to take risks that show promise and lead to more critical thinking that leads to strategic action. Local business units within an organization often balk at leadership edicts that are pushed down from the national or central organization. The self-generating organization allows for that local independence so that these units can better respond to local consumer needs. Indeed, business units need to figure out what new innovations mean to their markets, observe the results, and make adjustments to meet the market requirements. Thus, seeing ROD as a form of self-generation is the basis for CIOs to sustain innovative infrastructures that can respond to dynamic variables like technology.

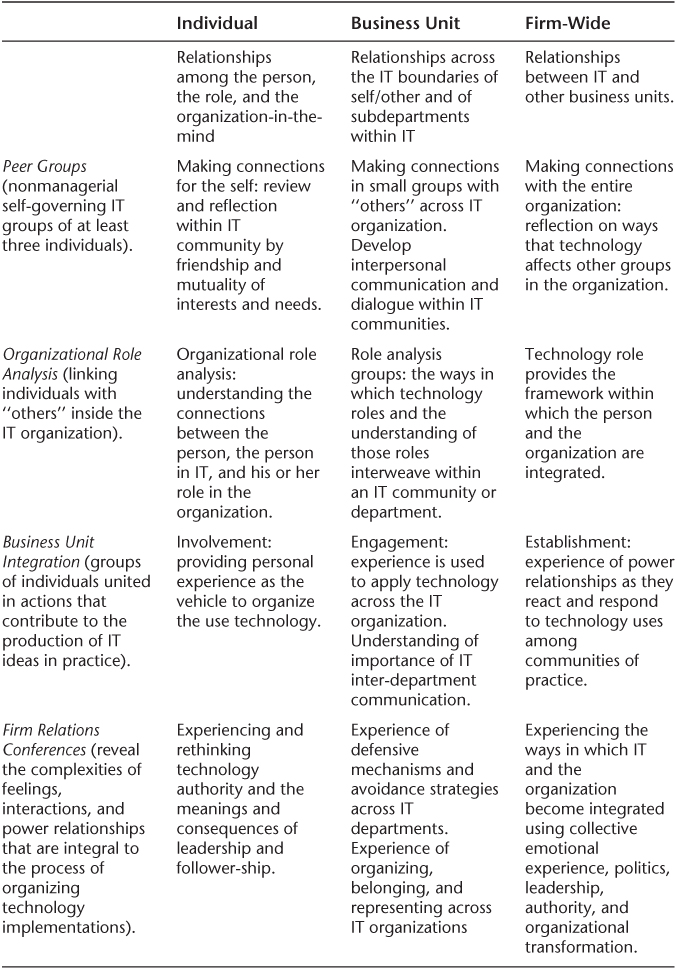

We believe that Vince's11 organized reflection model modified by Langer12 provides an analysis of how IT business integration could be used to sustain growth through evolution. Langer's modified model represents a matrix of how IT business integration can be measured across individuals, business units, and the firm as a whole. Langer's new framework is shown in Table 9.1.

Table 9.1 IT Business Integration Matrix: Examples of Reflective Practices for IT integration using Responsive Organizational Dynamism

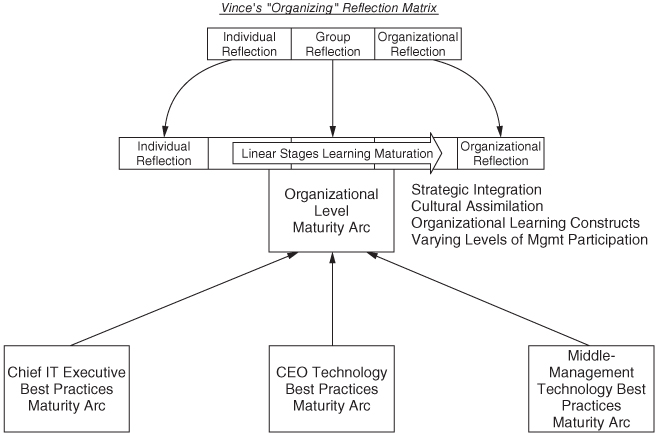

Table 9.1 shows the three kinds of reflective practices that can operate in an organization: individual, business unit, and firm-wide. We emphasized that the extent of the CIO's success in business integration is directly related to the level of strategic advocacy, not only by the CIO but also across the IT staff. Much of strategic advocacy requires individuals to have ability to reflect about their actions and how others around them view what they say and what they do. The better they understand that, in accordance with the maturity arcs, the more effective the IT department will be as a whole in integrating with the business. The more learning that occurs through individual reflections, the sooner business integration will be absorbed in the firm. When this occurs at the IT management and staff level first, it will inevitably have a positive effect on the business unit and firm-wide levels as well. Becoming more business integrated requires that the structured processes creates and maintains links between strategic advocacy, individual reflection and democratic thinking. These can be mapped onto the ROD arc, showing how, from an “organizing” perspective, strategic advocacy and reflective practices serves as a process to “outline what is involved in the process of reflection for learning and change.”13 Vince's model did not extend a structure for implementation for ROD. Langer's modification serves that very purpose, as shown in Figure 9.2.

Figure 9.2 Organizational Dynamism and Organized Reflection

Figure 9.2 graphically shows how organized reflection maps to the linear stages of the ROD arc (the organizational level maturity arc), which in turn maps onto the three best practices arcs discussed in Chapter 6. Each of the management arcs represent a level of management maturity at the organizational level, with Vince's matrix providing the overarching concepts on how to actually organize the progression from individual-based thinking and reflection to a more comprehensive and systems-level thinking using strategic advocacy. The emphasis, overall, is that individual actions of IT staff alone may undermine collective governance of the CIO. Therefore, the movement from individual to organizational self-management remains a critical part of understanding how technology and other dynamic variables can foster new strategies for competitive advantage. A competitive advantage that must be led by the CIO but carefully intertwined with the actions of the IT staff. The actions then of the IT staff must be mapped onto business units and then toward the entire firm collectively.

Our overall message in this book is that the CIO of today can become the chief of automation of tomorrow. The opportunity is staggering; the rewards can be many, including the potential of becoming the main road to the CEO position. With this challenge come many pitfalls and a poor history of accomplishing business integration, but as Bynjolfsson and Saunders cleverly stated in their recent book, Race Against the Machine; “the machine inevitably wins!”14 If we believe that automation will win, the issue then is whether a new generation of CIOs can take advantage of the opportunity that has been afforded to them. We can be sure of one thing, if they don't someone else at the C-suite will.

Notes

1 A. M. Langer, Information Technology and Organizational Learning: Managing Behavioral Change through Technology and Education, 2nd ed. (Boca Raton, FL: Taylor and Francis, 2011).

2 Ibid.

3 R. Johansen, A. Saveri, and G. Schmid, “Forces for Organizational Change: 21st Century Organizations: Reconciling Control and Empowerment,” Institute for the Future 6(1) (1995): 1–9.

4 H. Aldrich, Organizations Evolving (London: Sage, 2001).

5 A. S. Miner, and P. R. Haunschild, “Population and Learning.” In B. Staw and L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in Organizational Behavior (Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, 1995), 115–166.

6 S. P. Bradley, and R. L. Nolan, Sense and Respond: Capturing Value in the Network Era (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1998).

7 M. L. Tushman and P. Anderson, Managing Strategic Innovation and Change (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997).

8 W. Pietersen, Reinventing Strategy: Using Strategic Learning to Create and Sustain Breakthrough Performance (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2002).

9 J. Mezirow, Fostering Critical Reflection in Adulthood: A Guide to Transformative and Emancipatory Learning (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass,1990).

10 R. Johnsen, A. Saveri, and G. Schmid, “Forces for Organizational Change: 21st Century Organizations: Reconciling Control and Empowerment,” Institute for the Future 6(1) (1995): 1–9.

11 R. Vince, “Organizing Reflection,” Management Learning 33(1): 63–78.

12 A. M. Langer, “Responsive Organizational Dynamism: Managing Technology Life Cycles Using Reflective Practice. In Current Issues in Technology Management 9(2) (2005): 1–8.

13 Vince, “Organizing Reflection.”

14 Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee. Race Against the Machine (Lexington, KY: Digital Frontier Press, 2011).