Chapter 3

The Strategic Advocacy Mindset

Chapters 1 and 2 established the core challenge confronting chief information officers (CIOs)—namely, effectively engaging with senior executives in the strategic conversations taking place and integrating technology as a driver into these conversations. In the words of Chris Scalet, the former CIO at Merck for many years, “I would always start the conversation in terms of what is the meaning for the business. They are never IT conversations or IT projects; they are always business enabler projects.” As noted in Chapter 1, the CIO usually does not get visibility at an enterprise level. Chris Scalet and other successful CIOs get their seat at the table because they understand the business model and strategy of the organization and bring valuable insights for shaping strategy going forward.

According to Scalet, the CIO needs to be perceived as a businessperson who understands information technology (IT) and aligning it with the business. What we have argued in Chapter 2 as integrating IT as a driver of the business. The CIO needs to be stimulating dialogues with other senior executives. As also noted by Scalet, “Being around matters.” Communicating and building strategic relationships with other senior executives is the most important key for success as a CIO. However, establishing and leveraging these relationships requires overcoming the widely held perception noted in Chapter 1 of IT executives and managers as “techies.” This entails bringing a particular kind of mindset to these relationships, namely a strategic advocacy mindset.

What Is Strategic Advocacy?

By strategic advocacy we mean adding value to either the top or bottom line by cultivating alliances and establishing personal and functional influence through helping to define and respond to the adaptive and generative challenges that confront the organization and the possibilities they provide. Adaptive challenges are created by extensions and new applications of existing technologies and practices. Generative challenges emerge when new technologies transform the existing competitive landscape. In the case of the CIO, strategic advocacy involves connecting technology and the agenda of the technology function to widely ranging trends in the political economy of the organization within the context of shifting agendas among senior executives in the organization, each of whom has his or her own perspective on the shifting business interests confronting their part of the organization and the organization as a whole. Strategic advocacy is a process of consciously working within the patterns of power and influence in the organization to develop a sustainable base of support and credibility by being seen as aligned with both the strategic performance (drivers) and maintenance (support) requirements of the organization. This chapter presents a framework and sets of tools for developing and putting strategic advocacy into practice. A strategic advocacy is a way of thinking and acting.

Strategic advocacy involves drawing on two sets of competencies:

While these competencies have always been at the core of effective leadership initiatives around innovation, particularly for leaders of what have traditionally been viewed as support functions, in today's world of rapid emergent and innovative changes being driven by technology they have become even more critical for CIOs transitioning to the C-suite.

Broad technological innovations provide opportunities for strategic organizational change since such innovation plays an “unfreezing” function within the business environment and the organization. However, these innovations also generate initial resistance to change. Most people, including senior executives, respond to change with a focus on what they will lose, not on what they might gain or the collective benefits of the change. Fear of potential loss goes beyond attachment to tangible benefits and includes:

- A personal sense of identity as one has socially constructed it.

- The “known and tried” in terms of established skills and ways of working and coping.

- The established informal relationships on which one has come to depend.

- The existing sociopolitical context one has learned to navigate.4

This experience of loss is true of most people, including technology professionals, which explains why they initially resist abrupt transitions or transformational change. In a talk before students and faculty of the Executive Master of Science in Technology Management program at Columbia University, Chris Scalet described the history of technological innovation over the past 50 years, from mainframes to desktops to personal computers to the cloud. In each case, these innovations were initially resisted by leaders and experienced professional within the technology function. The innovative advocates at one phase of the cycle became initial resisters at the next phase.

When significant change occurs, a sense of loss is experienced immediately, while the benefits—assuming there are benefits—will be experienced in the future. Every technology professional has had the experience of making additions to an existing support system that users have grown comfortable with and experiencing reactions of frustrations from the users when they encounter the change, even though, from a technology perspective, new benefits have been added. Additionally, strategic changes at the C-suite level involve making choices with the outcome uncertain: There can be both a perceived “optimistic” and a “pessimistic” outcome of the process. Critical assumptions need to be made regarding:

- Market response from investors and customers.

- Responses from the competitors.

- Tangential events such as global political changes that impact the supply/distribution channels and regulations.

- The threat of new innovations or replacement products that will make the strategy obsolete even while it is being implemented.

In short, both the conversations prior to and shaping strategic choices and the subsequent action taken can produce unanticipated consequences that are complex. There are multiple interacting feedback loops working across sectors of the organizational context that make precise prediction of results impossible.5

This complexity takes place both in the external institutional environment and in the internal political dynamics of the organization. For example, conversations about possible challenges to the organization and the opportunities that may accompany them are part of informal interactions in the hallways, over dinner, while traveling, and in individual offices. Often, these informal conversations set the stage for what happens in formal meetings. These informal meetings become even more frequent and important when the organization is confronted with significant strategic threats. In the words of one senior executive, “when we finally acknowledge that major changes are happening in the marketplace is when suddenly there are a lot of informal, offsite after hour dinner meetings that take place among members of our executive committee.” All this complexity make the two skill sets that comprise strategic advocacy (again, engaging in strategic learning and action, and having political savvy for building social capital and effectively influencing others without relying on formal authority) key for effective engagement with other members of the senior executive team. Together, they comprise a particular type of mindset, one that is focused on the dynamic political economy of the organization.

The next section describes a political economy framework that encapsulates the scope of the necessary mindset for robust strategic advocacy. We then proceed to develop the practices for developing and exercising strategic learning and political savvy. First, however, we note that while we are making reference to senior executive teams and the C-suite, this framework and the practice of strategic advocacy applies to thinking and acting strategically throughout one's career in technology management, from individual contributor to midlevel manager positioning his or her function and new projects in the organization.

A few years back, Ram Charan, the globally recognized consultant and scholar on strategy and effective CEO actions, was addressing the Columbia Senior Executive Program. His presentation included a discussion on the importance of CEOs' recognizing the most significant potential threat to their business model and the common mistakes versus the most effective ways for CEOs to address the threat. As his presentation came to a close, he made the following comment, “The most effective CEOs don't begin thinking this way when they become appointed to the CEO position or the C-suite. They have been essentially thinking this way throughout their careers. It's the scope and nature of the threat to their business model that changes, not their way of thinking.” The lesson was “begin developing this way of thinking now—you don't start thinking that way when you become a CEO.” In fact, developing a strategic way of thinking can enhance both immediate effectiveness and the likelihood of eventually joining the senior team. The same principle applies to the next section. One doesn't develop a mindset for strategic advocacy when one becomes a CIO, as evidenced by the short retention spans of many new CIOs. The most effective CIOs have developed their way of engaging strategically throughout their career.

A Political Economy Framework for Contextualizing Strategic Advocacy

Organizations are open systems that are simultaneously both economic and political entities existing in a state of power dependency with other such entities that comprise a broader socioeconomic system. While these entities generally conform to the norms, values, and practices that comprise the institutional logics of their particular institutional sectors, they also must change in response to the disruptive actions of key competitors, the potential and threats of new technologies for their business model, and changes in their broader socioeconomic context. For these changes to happen and the organization to continue to thrive, the individuals embedded in them must act as agents stimulating and initiating innovation. In other words, engage in effective strategic advocacy.

This is easier said than done, particularly in organizations that have been highly successful, even by market leaders who have been innovators (consider the experience of Microsoft and Yahoo! over the past couple of decades), or are themselves embedded in deeply rooted institutional logics (e.g., higher education). The successful people comprising these organizations have internalized the practices that have made them and the organization successful (which explains the aforementioned resistance of technology managers to transformative changes in their field).

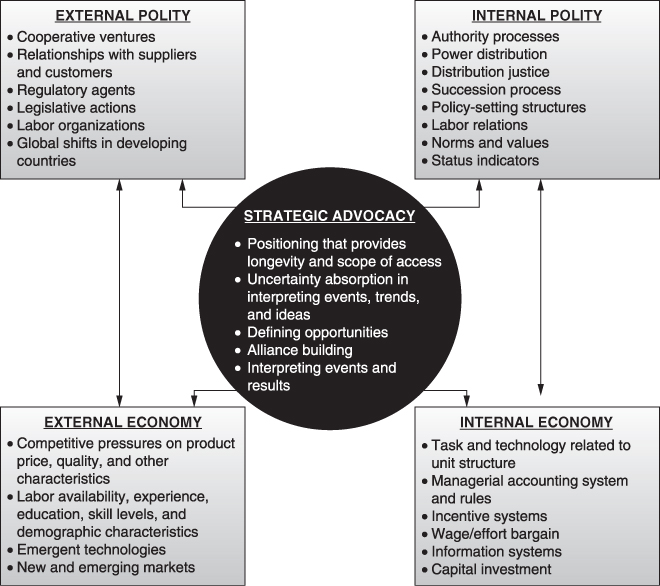

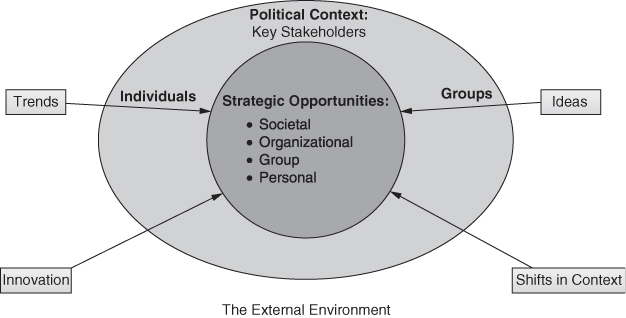

As previously noted, strategic advocacy on the part of CIOs and the technology professionals that work for them involves connecting technology and the agenda of the technology function to widely ranging trends in the political economy of the organization within the context of shifting agendas among senior executives. Strategic advocacy is a process through which CIOs and the professionals who work for them engage in political economy agency. A political economy framework maps key divisions, functions, and sectors within which actors in an organization need to track trends and interactions among these trends, and respond to the opportunities created and constraints imposed by the fluid interdependencies among them (these processes are mapped in Figure 3.1).6 The word trends is an important one; looking for patterns as opposed to thinking in terms of specific data points in time is the essence of strategic thinking.7 Remember the words of the cyberpunk novelist William Gibson: “The future is already here. It's just not evenly distributed yet.”8

Figure 3.1 A Strategic Advocacy–Focused Political Economy Model

There has been a productive tradition of using a political economy (P-E) perspective as a conceptual lens for the understanding and analysis of organizational dynamics.9 This perspective argues for the need to have a simultaneous focus on the interdependencies between the “polity” and the “economy” of the organization.10 This dual focus explicitly considers the relationship between the external and internal polities and economies.11 The strategic response to the opportunities and constraints afforded by the external political economy is determined through the interactions of a coalition of dominant actors in an organization's internal political economy.12

The term polity refers to the patterned use of influence within an organization and between the organization and social institutions.13 The economy is the productive exchange system of the organization and how it organizes work, generates value from its markets, and deals with innovation in terms of its relationships with customers and new product lines. Aligning the polity (internal and external) with the economy (internal and external) is a core function of strategy, and strategy formation is in part political,14 as is the process of dealing with the external strategic context—hence the necessity of CIOs' engaging in strategic advocacy given that technology is a critical strategic driver.

Although the model presented in Figure 3.1 is described in relationship to the senior executive's scope of responsibilities, it applies at any level of the organization. Organizations are complex and fluid systems inclusive of strategic business units, divisions, functions, departments, and groups. The boundaries at any level are arbitrary constructions open to redefinition as evidenced by current trends such as transferring tasks to customers, increasingly relying on “part-time” employees, contract workers, and outsourcing arrangements. The point of strategic advocacy is helping to shape the direction of this evolution through adding strategic value. At the middle levels of the organization technology managers need to think strategically as they advocate for changes in the existing support system.

Two analytical tools that are central to the literature on strategic planning that structure and formalize thinking about the political economy of an organization are:

The constraint in using these analytical tools is the potential for thinking to be constrained by the taken-for-granted assumptions and frames of reference that have become embedded in one's perspectives on their environment. To quote Albert Szent-Gyorgyi, 1937 Nobel Prize winner in Biochemistry, “Discovery consists of seeing what everyone else is seeing and thinking what nobody else has thought.”15 We turn now to the specific sets of practices and competencies associated with strategic advocacy: strategic learning and political savvy.

Strategic Thinking: A Particular Kind of Mindset

Increasingly, strategy theorists and researchers make a distinction between strategic thinking and strategic planning.16 Willie Pietersen, a former CEO and currently Professor of Practice in Executive Education at the Columbia Business School, summarized the fundamental distinction between strategy and planning very well.17 Strategic thinking starts from the context of the broader environment. It is:

- Outside-in, focusing on what is happening outside the organization.

- Noticing trends and patterns and seeking opportunities they will generate.

- Focusing on ideas and insights.

- Playing with divergent perspectives and thinking.

- Learning from diverse settings.

- Testing the viability of emerging opportunities through critical assessment of assumptions.

In contrast, planning is:

- Inside-out.

- Focusing on numbers.

- Convergent thinking.

- Allocating resources in support of execution of strategy and supporting programs.

Both are critical, but, in the words of Pietersen, “mixing them can be toxic.”18 Pietersen is making the point that in planning there is typically no divergent thinking that challenges existing assumptions and mental models of the world, no radically new insights into possible futures.

Each involves a distinct mindset. Planning involves an expert mindset, starting from the content of one's expertise. Methods and skills are applied to solve problems, providing answers, and focusing on “facts.” Expertise works within structured boundaries. Strategic thinking involves robust imagination valuing one's experience and expertise while seeking insight through observing new trends, pursuing diverse possibilities, and challenging one's assumptions. One of the authors often asks participants in his executive education workshops and strategy development classes, “Where does strategy come from?” The answers called out typically are “goals,” “the organization's mission,” and “its purpose.” The next question asked is “Where do goals, mission, and purpose come from?” Confused looks frequently follow. The answer is learning; strategic learning that challenges embedded assumptions, perspectives, and logics that block out new possibilities. We define strategic learning as a process of robust imagination, involving generating new insights, combined with learning through experience.

Strategic learning is easier said than done, as evidenced by the dominant companies who were once the innovators creating and driving their markets, but now find themselves behind the curve and even potentially becoming obsolete. While these dominant incumbents in an industry succeed in adapting and extending existing technologies, products, or services, they find it difficult to create something new. The reason is the struggle to let go of the past.19 Strategic thinking is a learning process seeking insights that emerge from raising provocative questions and framing new opportunities. Expert thinking focuses on logic and meeting predetermined goals as traditionally framed by self and others. Strategic thinking focuses on transforming the organization through framing new opportunities and challenging existing frameworks of thinking and activities associated with leadership; planning involves control and accountability, and is at the core of effective management.

Professional training involves cultivating expert thinking. Like many professions, IT professionals have developed an expert mindset reinforced by their intrinsic interest in working with and applying technology and technological innovation. The challenge that confronts them is complementing this expert mindset by also cultivating a strategic mindset. Returning to the previously cited observation of Ram Charan, one cannot wait until he or she is in the C-suite to begin developing this capability. If one enters the C-suite as CIO with only an expert mindset, it is too late.

As noted earlier, the key to developing a strategic mindset is focusing on the trends and patterns in different sectors and talking to people who hold diverse viewpoints. When Ram Charan was addressing the Columbia Senior Executive Program in the presentation previously mentioned, he asked the class, “How many of you are familiar with the Dell case?” They all raised their hands, which Charan knew would happen because the class had discussed the Dell case the previous week. “Fine” he said. “Today I want you to consider a different question. If you are Michael Dell, what's the biggest emerging threat to your business model?” The class broke into their teams for discussions. When they came back to the main classroom, Charan processed their thinking. While a range of interesting answers were reported by the various teams, only one group mentioned the emerging devices that could make laptops increasingly less dominant in the technology marketplace.

That's the critical question. What trend is on the horizon that is a potential threat to our business model, and what opportunities does it provide? The same question is relevant at the function and department levels as well. Speaking to the Executive Master of Science in Technology Management students at Columbia University in 2011, Chris Scalet stated, “In five years, the technology function as we know it will cease to exist.” He was trying to get the students to focus on making meaning of existing trends and the implications for strategically positioning themselves in the future. Successfully doing this involves engaging in a learning process that generates and leads to implementing breakthrough strategies.

In today's world of continuous dramatic change, this learning process involves a continuing course of action pursuing adaptive (extending existing technologies, products, and services) and generative (creating something new) change. We will argue in Chapter 7 that one's ability to engage in robust strategic learning requires a tolerance for ambiguity, and for dealing with incomplete, and even contradictory information. This is a developmental move from the structured thinking of the expert. There are specific practices that can facilitate this developmental move, while also enhancing one's strategic thinking.

This kind of mindset involves utilizing analytical tools such as PEST and SWOT as a classification system for capturing insights and a bridge between strategic learning and planning.

- Dialogue for considering diverse viewpoints.

- Reasoning through analogies both for envisioning new market possibilities and bringing into awareness how prior experience is shaping one's thinking.

- Scenario learning for generating new options and moving from divergent to convergent thinking and planning.

Yorks and Nicolaides argue that insight is the foundation of strategic learning.20 Strategic insight involves an increased awareness of new possibilities derived through engaging diverse perspectives, assessing trends in the various components of the political economy and challenging assumptions. The challenge is surfacing and testing assumptions and ideas, synthesizing trends and patterns across the political economy context into a plausible future storyline.

Engaging in Dialogic Processes

Dialogic processes can be defined as seeking to suspend assumptions and engage in genuine learning and thinking with others, as opposed to arguing for preferred outcomes.21 This involves asking open probing questions and listening without responding immediately with a reaction, further probing the points being made. This is particularly true when engaging with people holding different viewpoints or who have different experiences. The tendency is to think of and respond with a counterargument or to state why an idea won't work, rather than explore more deeply that other person's rationale.

In team or group meetings, dialogue can involve brainstorming ideas and proposals, picking the most radical ones for which a substantive argument has been made, and then collectively listing the possible benefits before considering the downsides.22 As the process unfolds, this often leads to seeing the advantage of what initially seemed to be an idea not worth pursuing. Even when the group then turns to considering the problems or downsides of an idea whose benefits had become clearer, if an insurmountable problem emerges for using the idea as stated there is a possibility of exploring alternative ways of achieving the same benefits.

Reasoning through Analogies

In their Harvard Business Review article, “How Strategists Really Think: Tapping the Power of Analogy,” Gavitte and Rivkin demonstrate how reasoning from analogy is often the basis for innovative thinking.23 Gavitte and Rivkin note how Charles Lazarus, the founder of Toys ‘R’ Us, used the analogy of the supermarket as inspiration for his idea for a new kind of toy store. Another is Andy Grove of Intel, learning from how the U.S. steel industry ceded the low end of the business to mini-mills only to see them move into higher-end products, “seized on the steel analogy, referring to the cheap PC as ‘digital rebar,’” changing Intel's resistance to providing cheap microprocessors for inexpensive PCs arguing that if they conceded the low end today they can lose the high end tomorrow. Gavitte and Rivkin define reasoning through analogy as the process through which a person…” faced with an unfamiliar problem or opportunity…think back to some similar situation they have seen or heard about, draw lessons from it, and apply these lessons to the current situation.”24 When used properly analogies can generate new insights for strategic opportunities. However, analogies can be dangerous when the persons using them act “on an analogy on the basis of superficial similarity” and fail to carefully assess it.25

Gavitte and Rivkin offer a process of mapping analogies in order to test the insight being offered:

- Actively searching for differences by first thoroughly assessing the factors that comprised the causal traits or characteristics that made the source analogy successful.

- Carefully testing similarities between the above and the situation it is being applied to, testing for similarities between the two situations and identifying key differences.

- Surfacing the presumptions behind asserted crucial correspondences between the two situations, by asking critical questions around what is known, what are the maybes, what is unclear, and how maybes can be turned into either known or unclear. Also, asking what emerges if the presumptions are reframed.

- Modeling the landscape.

The testing of presumptions can be carried out by utilizing what we call the learning window (see Figure 3.2):

- Cell one, what do we know and why we know it because we have solid data that has been confirmed and its interpretation is widely accepted.

- Cell two, what do we think we know and what we need to discover in order to know it because there are some data, but it is inconclusive.

- Cell three, what do we know we do not know, and is it possible to get information or data that would move us to cell one or cell two?

- Cell four, staying open to the unexpected as we continue to explore the analogy.

Figure 3.2 The Learning Window

Yorks and Nicolaides argue an explicit focus on mapping analogies has another potential benefit, especially under conditions of uncertainty and complexity.26 Analogies, whether consciously used or not, are a primary way in which informal and incidental learning from experience27 is subsequently enacted. Under conditions of uncertainty and complexity experience is a double-edged sword, having value but also potentially not being applicable in the new situation. Seeking to make explicit these analogies that comprise one's experiences that are being subconsciously drawn upon is a way of valuing experience and being aware of its potential barriers to new insights or adopting new courses of action. Often, questioning by others during strategic dialogues brings awareness of how one is drawing on one's experience and provides a way of reflexively assessing its value in the current situation. Listening to questions from others, answering, and then inviting them to share what they think one is assuming (I believe you are assuming that…) is one way of structuring such a dialogue.

Scenario Learning

Unlike problem solving, one never really knows how a strategic decision is likely to play out. Indeed, ongoing adjustments during a strategy's implementation are almost always necessary. Given this reality, the idea behind scenario learning is learning from the range of possible futures and then, taking into account the level of risk that is acceptable, making a decision. Scenario learning is a form of vicariously “learning from the future.”28 As such, it can also prepare one for the uncertainties that might emerge once the strategy is being implemented. Scenario learning is a process that can generate new insights while moving the strategic conversation toward convergence and making decisions.

Consistent with the distinction between strategic thinking and planning, Fahey and Randall “prefer scenario learning to the more common term scenario planning for a number of reasons.”29 Among them is the reality that to be truly effective in addressing conformation bias (seeking only supportive evidence for an idea) managers must be willing to “suspend their beliefs, assumptions and preconceptions.” For Fahey and Randall the term “learning implies…dialogue.…Managers and others…must engage each other in a free ranging exchange of ideas” provoking “some degree of tension…. Such tension is the essence of collective learning.”30

While computer-driven simulations are useful for modeling potential scenarios, the higher the degree of uncertainty in the environmental context being simulated, the greater is the level of incompressibility on the reliability of the simulation.31 Incompressibility refers to the fact that in building such simulations of open systems we are forced to leave things out. Since the effects of these omissions are nonlinear, we cannot predict their scale of impact. While simulations are often the only way to get a feel for the dynamics of complex systems, it is important to avoid the expert mindset tendency of seeing them as providing predicable answers. Rather they are part of the data base for learning.

Again the importance of dialogue for the strategic learning process has been raised by Fahey and Randall. Chantell Ilbury and Clem Sunter32 have provided a thinking framework that is both a way of fostering one's strategic mindset and structuring a dialog around possible scenarios. It involves four cells, moving from relative certainty, through an absence of control, high uncertainty, to relative control.

- The first step is to identify the rules of the game, meaning what are the given boundaries of the context within which one would be taking action. These might include laws, regulations, financial givens, and the like. There are constraints that are taken for granted. In some instances, they need to be verified.

- The second step involves brainstorming the key uncertainties that exist and might significantly alter the outcome.

- A third step is translating how these uncertainties would play out in terms of possible scenarios.

- Focusing on three or four scenarios that provide a range of possible outcomes will lay out what options exist in terms of possible actions.

- Based on analysis of the options and level of risk tolerance, a decision regarding taking action can be made.

- Once a decision for action is made, lay out plans B and C for adjusting the action.

In thinking strategically at the organization level, the focus is on implications for the business model. In addition to being practices that can be used in formal strategy conversations, they can also be used as informal ways of framing hallway, lunch, or dinner conversations that are the basis for stimulating thinking about the strategic context. The tools don't even have to be mentioned by name. “You know this is like…” is one way of informally initiating informal strategic conversations using reasoning by analogy. “Thinking about the action we are considering, three things come to mind as possible events that could mediate what we want to do…. A couple of different scenarios come to mind.” In both cases, the models are held in one's head as a way of thinking.

Strategic thinking is one aspect of strategic advocacy, arriving at insights that can be the basis for strategies that add value to the organization. Political savvy is the other. We turn now to this critical competency.

Political Savvy as the Underpinning of Effective Strategic Advocacy

We have taken the term political savvy from Joel DeLuca, who defines it as “ethically building a critical mass of support for an idea you care about.”33 Although in popular culture the word politics carries negative connotations, in practice little significance, positive or otherwise, occurs within complex organizations without political initiatives.34 When things go right, we refer to who effectively applied influence; when they go poorly, we use the term politics to express negative experiences. Straightforwardly, defined organizational politics are “how power and interests play out in the organization”35 and political agency in the context of the organizational political economy is the process of participating in this “play.” As DeLuca notes, organizational politics is a double edge sword, with one edge representing the actions of those who pursue self-interest through Machiavellian and deceitful methods and the other edge seeking to use influence that links multiple agendas to broader organizational interests. The first is dysfunctional politics, the second, functional.

At the heart of strategic advocacy is seeking to see in the patterns of an organization's political economy opportunities for both adding value and developing the relationships that will make this possible. Any executive or manager who, when considering how to effectively advance a proposal, says to a colleague, “let's think strategically about this,” is moving into the realm of politics. DeLuca notes that, “political savvy is not about acquiring power; it is about making an impact in specific situations.” Likewise it is not about proper exercise of authority, but influencing those with authority to make the decision. “Political savvy has little to do with one's place in the hierarchy. The clerk who automates the mail room despite resistance may have more political savvy then the CEO who makes things happen by giving orders.”36

Political savvy, as used here, does not imply “pushing through” one's ideas intact. Rather, the goal is to have an open and useful conversation that gives the idea a hearing and thorough assessment, sometimes resulting in modification or even a decision not to pursue. It involves taking into account the legitimate agendas of other stakeholders, seeking to develop a win-win that really does provide value to the organization. Politically savvy executives and professionals align their interests and others' to the collective interests of the organization. Strategic advocacy requires thinking strategically across multiple sectors of the organization's political economy. As discussed earlier, this includes thinking strategically in terms of opportunities at the societal, organizational, group, and personal level for adding value to the organization. It also includes thinking strategically in the political context of the key stakeholders. What does this mean in practice? The following are six strategic actions for developing and practicing political savvy:

Mapping the Political Territory

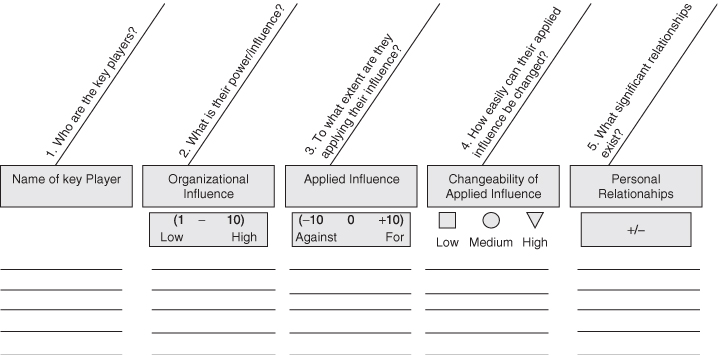

Developed by DeLuca, mapping the political territory provides an overview of the key stakeholders, the perceived potential supporters and opponents of one's proposed plan or project along with the relationships among them. More important, the map provides focus for reflecting on the assumptions one is holding and strategizing a course of action. In creating the map, five questions are asked (see Figure 3.3).

Figure 3.3 The Political Data Sheet

Source: J. DeLuca, Political Savvy: Systematic Approaches to Leadership Behind-the-Scenes (Berywn, PA: EBG, 1999).

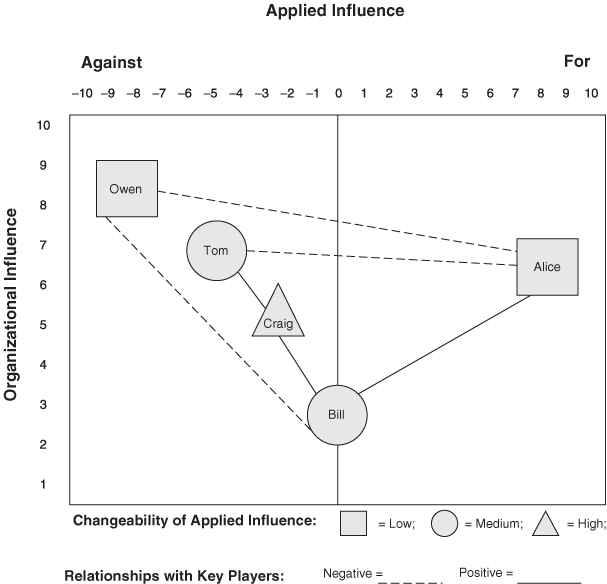

The answers to these questions can be placed on the analytical tool illustrated in Figure 3.4. Ranking their power/influence involves relative judgments for thinking and discussion purposes among team members. It is important to consider the particular project since some stakeholders have a relatively stable degree of influence on the key decision maker; others may have more or less influence, depending on the topic and their expertise. The assessment of how they are likely to apply their influence is a relative, subjective ranking ranging from positive 10 through neutral to negative 10. Again, these are relative judgments.

Figure 3.4 Organization Politics Map

Source: J. DeLuca, Political Savvy: Systematic Approaches to Leadership Behind-the-Scenes (Berywn, PA: EBG, 1999).

Their assumed changeably is depicted as either a circle meaning possibly changeable, and square representing an assumed fixed position, and an upside down triangle meaning not a fix position and highly changeable one way or the other. Relationship connections should be reserved for consistently strong ones, either positive (represented by a +) or negative (represented by a −). When placed on the map (Figure 3.4), the result is a map that can begin to trigger strategic thinking regarding political advocacy. This is particularly powerful when the map is used for dialogue among team members preparing to propose an innovative project.

It is important to remember that the map is not the territory itself. Positions will change. Some important initial questions include: What is one's “data” for the assessments made? and What assumptions is one holding about the key stakeholders and how can they be tested? It is actually useful to begin developing the map when assuming a new position to begin building a critical understanding of the context. For the new CIO, senior management meetings are opportunities for engaging in what researchers would call field observation. Considerable learning can take place during informal conversations. A mid-level IT manager mapping the territory in preparing to strategically advocate for what he believed was a necessary project found the range of stakeholders to be included expanded beyond his initial mapping. The more he considered the map and reflected, the more he realized he had limited his interactions in the organization.

The map is a tool that raises questions for thinking about how to exercise leadership through strategic advocacy. The most effective executives intuitively consider the variables in the map when deciding on a course of influencing action. In the case of very important initiatives, making the process explicit can lead to a more thorough assessment and a more robust strategy-making process. In the case of CIOs and others in the IT function, they need to have several maps in their heads—one that indicates the position that key senior executives hold regarding technology in general and others linked to particular initiatives that are being proposed.

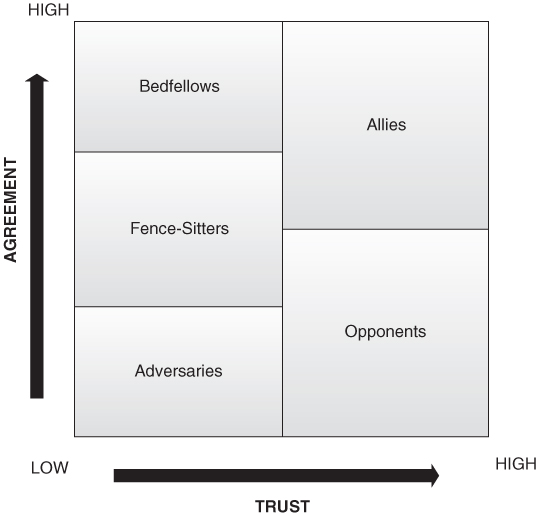

Assessing the Trust/Agreement Matrix

An important initial assessment is to impose the trust agreement matrix (see Figure 3.5) on the map of the territory, making critical distinctions between allies, opponents, and adversaries.37 Opponents are those who may generally disagree with you but can be trusted. Adversaries are those who disagree with you and can't be trusted. For example, they may be friendly face to face but act behind your back. On particular projects, opponents may be bedfellows on a particular issue because they agree with the need for the particular initiative or strategic move being advocated because it aligns with their interests. What other allies might be cultivated who are not on the initial map is another critical question.

Figure 3.5 The Trust/Agreement Matrix

Source: Peter Block, The Empowered Manager: Positive Political Skills at Work (San Francisco: Josey-Bass, 1987), p. 132.

Linking Agendas

Thinking through how the initiative can be modified, the technical design adapted, or new components added to meet the diverse agendas of key stakeholders can often both result in more value for the organization and create more support. Particular consideration should be given the agendas of stakeholders who are somewhat resistant (0 to −5 on the map), but linking agendas can change the position of even a negative 9 or 10, perhaps turning an opponent or fence-sitter into a bedfellow on this initiative. Also, linking agendas might minimize resistance coming from a reaction to the sense of loss that might be experienced.

Utilizing Currencies

Cohen and Bradford describe several types of currencies that can be used when exercising influence.38 Currencies are resources that are useful to others in the organization and therefore have an exchange value in building and sustaining alliances. Some currencies are relatively tangible, such as information, time, or task support. Other currencies are more intangible but often just as valuable, such as lending personal support, recognition, or visibility to others. CIOs and IT managers and professionals need to build reservoirs of currencies that can become the lifeblood of their work within the organization.

Following the Credibility Path

Looking at the relationships on the map and alliances in the CIO's social capital network provides insight into the credibility path.39 The credibility path rests on the principle that influencing someone about a decision often turns on who is the messenger making the proposal. Convincing others of the value of a proposed idea frequently depends on who communicates the idea. Sometimes it makes sense to let others take the lead, particularly when advocating to a key stakeholder with whom the CIO or technology professional does not have a positive relationship. This is a good use of allies. Actually, the term credibility path was used by a highly successful CIO during one of our interviews:

The (business unit) CEO has for a number of years been a very strong supporter of technology. He recognizes how technology can be an enabler for his business and be a driver for his business. We have built a lot of proprietary forums for him…. So we have a CEO who is a strong supporter of the function and we have people embedded in that service line. We use the success there to demonstrate how we can enable other service (business) lines. It's following the credibility path.

Effective influencers often follow the credibility path letting whoever has the most credibility carry the idea forward.

Developing Social Capital through Networks and Coalitions

Another critical strategic action is pursuing opportunities for cultivating informal networks that can be used for developing coalitions in support of particular projects. Such networks are a form of social capital, which are networks that provide executives with access to a variety of resources. Social capital can be seen as actual and potential resources from network and coalition relationships developed by individuals or organizational units. Social capital networks are social structures made of nodes (individuals or groups)40 that are joined by various interactions such as business and personal relationships. Positioning oneself as the “node” that can provide connections between otherwise separate networks is a way of leveraging one's ideas and also establishing new credibility paths.

Social networks are an avenue for raising awareness and cultivating understanding. Coalitions provide for maneuverability by enhancing options through multiple credibility paths, taking coordinated action, and increasing the range of possible currencies. They also provide opportunity for surfacing potential objections and shaping perceptions. This is why being out in the organization is so critical.

Conclusion

Use of the tools and practices presented throughout this chapter requires bringing a strategic mindset to one's thinking. The same kind of thinking is necessary for arriving at:

- New, generative strategic insight about how technology can be integrated into the business model to enhance its value as a driver.

- Insights regarding how to best navigate the political system and build effective relationships.

Like practitioners in other professions, many IT professionals have an expert mindset that often works well with other IT professionals when they are engaging in technical advocacy. When dealing with executives outside the IT profession, this mindset fails to build effective relationships. The impact from an influencing perspective can be summarized as:

Building strategic relationships through strategic advocacy can be summarized as:

![]()

While this chapter focuses on the individual, the same logics apply among groups and other organizations. Noticing what trends and shifts are taking place in the broader context and the emerging ideas and innovations that potentially impact the strategic positioning of one's organization provides the substance for strategic advocacy (see Figure 3.6). This is the true complexity of the organization's political economy and the need for strategic learning.

Figure 3.6 The Complex Strategic Advocacy Context

Of course, another challenge is moving from divergent to convergent thinking testing insights through one's social network. Integrating the strategic insights gleaned from assessing trends in the institutional context with trends in the political dynamics of the organization is key to establishing influence in the organization as one participates in the business conversation.

This chapter has presented key frameworks for meeting the CIO challenge. In Chapter 7, we present a more thorough discussion of the process for developing the strategic advocacy mindset. In Chapter 4, we turn our attention to cases derived from successful CIOs that illustrate the way this mindset emerges in practice.

Notes

1 W. Pietersen, Reinventing Strategy: Using Strategic Learning to Create and Sustain Breakthrough Performance (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2002).

2 J. DeLuca, Political Savvy: Systematic Approaches to Leadership Behind-the-Scenes (Berywn, PA: EBG, 1999).

3 A. R. Cohen, and D. L. Bradford, Influence without Authority, 2nd ed. (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2005).

4 W. W. Burke, Organization Development: Principles and Practices (Boston: Little Brown, 1982).

5 K. A. Richardson and A. Tait, “The Death of the Expert?” In A. Tait and K. A. Richardson (Eds.), Complexity and Knowledge Management: Understanding the Role of Knowledge in the Management of Social Networks (Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing, 2010), 23–39.

6 L. Yorks, “Toward a Political Economy Model for Comparative Analysis of the Role of Strategic Human Resource Development Leadership,” Human Resource Development Review 3 (2004): 189–208.

7 W. Pietersen, Strategic Learning (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2010).

8 Quoted in Pietersen, Reinventing Strategy.

9 J. K. Benson, “The Interorganizational Network as a Political Economy,” Administrative Science Quarterly 20 (1975): 229–249; R. E. Cole, “The Macropolitics of Organizational Change, Administrative Science Quarterly 30 (1985): 560–585; L. W. Stern and T. Reve, “Distribution Channels as Political Economies: A Framework for Analysis,” Journal of Marketing 44 (1980): 52–64; D. R. Van Houten, “The Political Economy and Technical Control of Work Humanization in Sweden during the 1970s and 1980s,” Work and Occupations 14 (1987): 483–513; G. L. Wamsley and M. N. Zald, The Political Economy of Public Organization (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1976); L. Yorks and D. A. Whitsett, Scenarios of Change: Advocacy and the Diffusion of Job Redesign in Organizations (New York: Praeger, 1989); L. Yorks, “Toward a Political Economy Model for Comparative Analysis of the Role of Strategic Human Resource Development Leadership,” Human Resource Development Review 3 (2004): 189–208; M. N. Zald, Organizational Change: The Political Economy of the YMCA. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970); M. N. Zald, “Political Economy: A Framework for Comparative Analysis.” In M. N. Zald (Ed.), Power in Organizations (Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press, 1970), 221–261).

10 J. Arndt, “The Political Economy Paradigm: Foundation for Theory Building in Marketing,” Journal of Marketing 47 (1983): 44–54.

11 Zald, Organizational Change.

12 R. E. Miles and C. C. Snow, Organizational Strategy, Structure, and Process (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1978); A. M. Pettigrew, The Awaking Giant: Continuity and Change in ICI (Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell, 1985); J. Storey, “Management Control as a Bridging Concept,” Journal of Management Studies 22 (1985): 269–291.

13 Zald, “Political Economy.”

14 I. C. MacMillan, Strategy Formulation: Political Concepts (New York: West, 1978); I. Palmer and C. Hardy, Thinking About Management: Implications of Organizational Debates for Practice (London: Sage, 2000); A. M. Pettigrew, The Politics of Organizational Decision-Making (London: Tavistock, 1973); Pettigrew, The Awaking Giant.

15 Pietersen, Reinventing Strategy.

16 See, for example, E. D. Beinhocker and S. Kaplan, “Tired of Strategic Planning?” McKinsey Quarterly (August 3, 2007); V. Govindarajan and C. Trimble, “Strategic Innovation and the Science of Learning,” MIT Sloan Management Review 45(2) (2004): 67–75,; B. Leavy, “The Concept of Learning in the Strategy Field,” Management Learning 29 (1998): 447–466; D. P. Lovallo and L. T. Mendonca, “Strategy's Strategist: An Interview with Richard Rumelt,” McKinsey Quarterly (2007), www.mckinseyquarterly.com/Strategys_strategist_An_interview_with_Richard_Rumelt_2039.

17 Pietersen, W. Reinventing Strategy.

18 Ibid.

19 H. Penton, Material from conversation and presentation at a Saudi business school, 2011.

20 L. Yorks and A. Nicolaides, “A Conceptual Model for Developing Mindsets for Strategic Insight under Conditions of Complexity and High Uncertainty. Human Resource Development Review, 11 (2012): 182–202.

21 Ibid.

22 G. M. Prince, The Practice of Creativity (New York: Collier Books, 1970); Yorks and Nicolaides, “A Conceptual Model for Developing Mindsets for Strategic Insight.”

23 G. Gavitte and J. W. Rivkin, “How Strategists Really Think: Tapping the Power of Analogy,” Harvard Business Review (April 2005): 54–63.

24 Ibid., p. 54.

25 Ibid., p. 57.

26 Yorks and Nicolaides, “A Conceptual Model for Developing Mindsets for Strategic Insight.”

27 V. J. Marsick and K. E. Watkins, Informal and Incidental Learning in the Workplace (London: Routledge, 1990).

28 Yorks and Nicolaides, “A Conceptual Model for Developing Mindsets for Strategic Insight.”

29 L. Fahey and R. M. Randall, “What Is Scenario Learning?” (Ch. 1), and “Integrating Strategy and Scenarios (Ch. 2). In L. Fahey and R. M. Randall (Eds.), Learning from the Future (New York: John John Wiley & Sons & Sons, 1998), 3–38.

30 Ibid., p. 5.

31 P. Cillers, “Knowing Complex Systems.” In K. A. Richardson (Ed.), Managing Organizational Complexity: Philosophy, Theory, and Application (Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing, 2005), 7–19.

32 C. Illbury and C. Sunter, The Mind of a Fox (Cape Town, South Africa: Human & Rousseau/Tafelberg, 2001), 36–43.

33 DeLuca, Political Savvy, p. 112.

34 Pfeffer, J. Managing with Power: Politics and Influence in Organizations (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1994).

35 DeLuca, J. Political Savvy, p. 44.

36 Ibid., pp. 112–113.

37 P. Block, The Empowered Manager: Positive Political Skills at Work (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1987).

38 A. R. Cohen and D. L. Bradford, Influence without Authority, 2nd ed. (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2005).

39 Ibid.

40 J. Nahapiet and S. Ghoshal, “Social Capital, Intellectual Capital, and the Organizational Advantage,” Academy of Management Review 23 (1998): 242–266; N. M. Tichy, M. L. Tushman, and C. Fombrum, “Social Network Analysis for Organizations. Academy of Management Review 4 (1979): 507–519.