Chapter 8

The Non-IT CIO of the Future

This chapter attempts to foresee the future of the chief information officer (CIO) position. We have presented in previous chapters the responsibilities challenging CIOs today, and using future trends we forecast some of the short and long-term opportunities of the CIO. We see the position migrating toward more of a chief of automation's being functionally responsible for contracts, equipment management, general automation, and outsourcing while having a central role in conversations strategically leveraging emerging new technologies. We believe that the term CIO needs to be reinvented, with less focus on the information technology (IT) side and much more emphasis on automation and innovations that will continue to drive new business opportunities while lowering costs.

The first aspect of attempting to forecast the CIOs of the future is to avoid trying to predict their new title, rather to explore more the roles and responsibilities that these executives will need to manage. To be consistent with our research findings, we start with Langer's driver-support theory, which addresses much of the future needs of the position.

Driver-Side Responsibilities—New Automation

CIOs of the future will need to spend much of their time with the business, helping to develop strategic advantages through applications of automation. Note that we use the term automation as opposed to IT or even technology. We think this is a critical shift in responsibilities. Indeed, not all automation implies information-based solutions. Automation needs are inclusive of equipment, media, engineering, and biotechnology, to name just a few. All of these automations need to be seamlessly integrated and managed through central sources to really provide effective cost savings as well as maximum strategic value. As we advocated in Chapter 1, ultimately the CIO of the future will need to lead all kinds of business transformations in the organization. Indeed, no transformation can be accomplished without the uses of modern automation considerations.

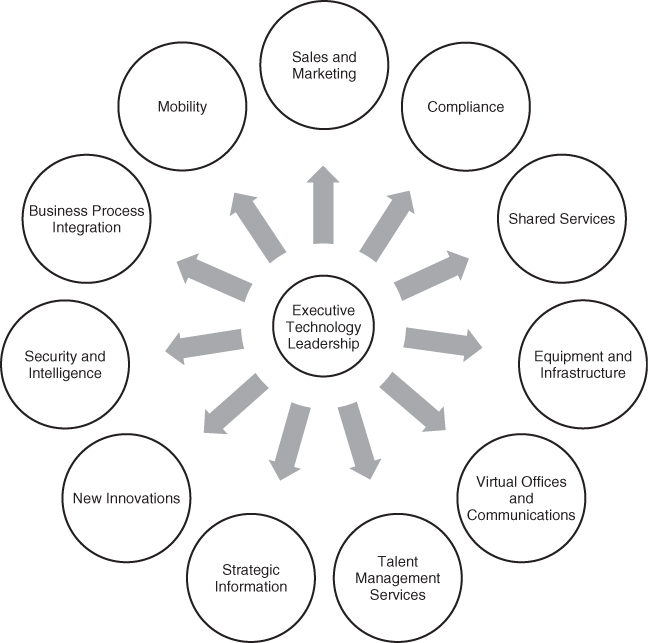

Some of these transformations we foresee include:

- Sales and marketing

- Compliance

- Shared services

- Equipment and infrastructure

- Virtual offices and communications

- Talent management services

- Strategic information

- New innovations (disruptive technologies)

- Security and intelligence

- Business process integration

- Mobility

Each of these strategic automations will be expanded in this chapter.

Sales and Marketing

Technology continues to be a driving force on new ways of reaching customers and consumers. Salesforce, for example, has had major impacts on how salespeople penetrate new and old markets. Technology will continue to provide new techniques. The impacts of how to use automation applications such as Facebook have established new ways of how organizations build relationships with its buyers and sellers.

Because more and more customer information is now digital, having marketing information available is far more critical. Indeed, consumers are using the Internet and social media for commerce, and we see future activities to be continually being driven by automation capacities. The fascinating unknown is the extent of future need for traditional sales and marketing personnel. We believe technology will place tomorrow's automation executives at the forefront of driving sales revenues in many organizations. Simply put, markets have become too large for direct methods of penetration. The use of analytics and cloud technologies will dramatically change this. Recalling our interview with Passerini, IT was instrumental in creating an advanced approach to doing focus groups, and at lower cost.

So, will today's CIOs become tomorrow's chief marketing officers? Will technology inevitably drive sales? If so, we believe that both chief positions may indeed gravitate to a new “automation officer.” Gartner recently predicted that by 2017 marketing officers will spend more on technology than the CIO. With these two skills becoming more important for the customer advantage, we believe that it will likely be easier for the CIO to learn about marketing needs than vice versa.

Results released by an IDG Research Services survey in 2010 showed that CIOs are already transitioning toward important support for sales and marketing—particularly with respect to “customer interaction.” The survey showed that over two thirds of CIOs stated a need to overhaul sales systems and processes and another 54 percent felt there was a need for better business intelligence.

Compliance

We expect compliance, especially for regulatory bodies, to continue to increase as the power of technology touches more critical parts of consumer life. The costs to meet compliance requirements are significant and creating methods to reduce these costs while meeting the requirements is key for every business. This is particularly critical for public firms that must comply with Sarbanes-Oxley and Regulation Fair Disclosure (known as Reg FD). Furthermore, firms are pressed to preserve antidiscrimination compliance—all becoming increasingly more difficult with the way in which employees communicate across discoverable channels. In many ways, it appears that today's CIOs may need to handle the role of an “interrogator” in addition to their regular responsibilities. Yet we know that automation of communication has salient exposures—it drives corporate legal attorneys crazy with the apparent number of violations that occur in business every day.

In 2011, Michael Schrage wrote a blog in the Harvard Business Review titled, “Should CIOs Be Compliance Cops?” He states that there is a growing need to police employee compliance that may “offer an important opportunity for the CIO and IT to powerfully influence personnel and privacy policies at the firm.” Schrage believes that CIOs should be wary of just becoming the “Big Brother” watching and policing activities, rather to take the opportunity to drive conversations of how to implement procedures and policies that can guide compliance instead.

Compliance requirements are not just limited to the United States. There are stringent European Union (EU) rules today that forbid firms from taking user data without first getting permission. The United Kingdom recently announced that they will adopt the EU compliance law and according to Schectman's June 2012 article in the Wall Street Journal's CIO Journal, there is speculation that the United States may not be far behind. To date, there are over 100 federal and state regulations that are designed to protect the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of electronic data.1 These regulations do not include yet another layer of rules that typically restrict industry specific uses of information technology.

Intellectual property (IP) violations are yet another area of compliance that needs close focus from technology executives. The automation, in agreement with legal counsel, is becoming a major area of legal exposure. From a legal standpoint, CIOs need to prepare for the “growing need for standards and benchmarks by which automated search tools can be measured to show their reasonableness and defensibility when used in a legal context.”2 Therefore, technology leaders will need to take efforts along these lines and accelerate integration to protect IP and other legal exposures both nationally and internationally. This can be accomplished only with advanced automation techniques that can uncover potential legal exposures.

Shared Services

Shared services is a growth area of responsibility for CIOs interested in expanding their responsibilities. Shared services is designed to allocate resources to one “shared department,” rather than separate entities each having their own dedicated resources. Given the opportunity to centralize and share resources, potential automations can also provide cost reductions simply because firms need less people. The challenge, of course, with shared services is to avoid the pitfalls of creating a bureaucracy and to provide quality services that meet local department needs.

Cloud computing is an example of an automation of shared services that resides within the domain of the CIO. It is likely that the continued advancements in cloud-type technologies will only expand the need for more shared service applications. Businesses are aware of this opportunity, and CIOs have an opportunity to be part of extending this service offering to the organization while expanding their domain of responsibilities. This is an important area of expansion because of the ultimate complexity of cloud and the predictable new innovations that will make it more robust. Some professionals have even labeled shared services as “hybrid IT.”

It would be tunnel vision for future automation executives to think of shared services only as a new way of providing IT services at a reduced cost. Indeed, the overall mission to provide shared services is to cut costs. But strategic leaders see a lot more. The benefits of shared services should also provide opportunities for organizations to better share information across their own network of businesses, particularly in human resources (HR) and finance. This means that common practices and benefits learned from shared services will improve collaboration across departments and functions. Another way of stating this benefit is that shared services can provide a communication channel that improves collaboration. Improved collaboration can then increase productivity. Furthermore, shared services allows for more standardization of processes and services, especially for the internal users of the system. Standardization can also lay the foundation for better innovations, with continued improvements that can respond to ROD-based disruptions. Today, 90 percent of the top 1000 companies have used some type of shared services model.

So evolving CIOs should be seeking opportunities to expand what is traditional IT shared services to a blend of corresponding functions—all of which will benefit from levels of automation. Technology executives of the future will treat shared services as an activity that continues to evolve and react to market needs as opposed to just an activity that supports a central service.

Equipment and Infrastructure

Obviously, CIOs are heavily involved in automation of technology infrastructure. Indeed, IT typically represents the largest part of a firm's capital expenditures. A number of CIOs have responsibilities for other equipment such as copy machines. Furthermore, some CIOs are now responsible for office space and other infrastructure facilities.

Overall, we see that technology executives will be responsible for integrating all machinery requirements and space allocations. This will likely be accomplished via sophisticated central portal systems that have the ability to dynamically improve the efficiency and return on investment (ROI) of products and services. These centralized systems will be able to access multiple points along a highway of networked locations around the world—it will be an “automation central.” Using open and modular systems, technology executives will be able to:

- Centralize data management

- Cross-reference systems

- Do dynamic diagnostics on applications

- Scale systems to meet peak demands

- Simulate possibilities and predetermine how systems will perform

- Provide better security and safety

From a CIO perspective, the listed items fall under a larger category called infrastructure management (IM). IM typically includes systems management, network management, and storage management:

- Systems management. This is a look at the enterprise level of the organization and includes understanding the entire needs of the firm and providing for the purchasing of various equipment, software, and maintenance. Maintenance covers support, service updates, setup of equipment, and coordination of delivery.

- Network management. This represents the connectivity of multiple layers and types of computer equipment through various types of physical devices. Networks have traditionally been limited to applications support, but we see this area expanding into different types of requirements especially for security, data, video, and wireless devices. All of these new networks must have the necessary operating policies and procedures to be managed centrally but with a distributed architecture.

- Storage management. This is one of the significant challenges faced by organizations today. Storage management entails the overall ability to store and secure various forms of data and information. The storage of data is complex, especially as it relates to the kind of access needed and by whom. Storage also involves other than stored data files such as compressed music files or voice messages.

The necessity for technology executives to manage this growing area requires remote and sophisticated software that will ultimately reduce costs, protect information, and work to better integrate the wide variance of types of equipment in an enterprise.

Virtual Offices and Communications

The growth of virtual offices has been significant over the past 10 years and will likely continue to grow exponentially with the expansion of global organizations. Addressing virtual office challenges typically uncovers the need for improving communications among the offices themselves, especially across different countries and cultures.

IT has been the main driver of the growth of virtual teams simply because it makes it possible. It is IT that has vastly improved the development of competitive outsourcing abroad in such countries as India, China, Brazil, Ireland, and many others. These countries are not only physically remote, but they also present barriers of culture and language. These barriers often impede communications about project status and affect the likelihood of delivering a project timely and within forecasted budgets.

Despite these major challenges, outsourcing remains attractive due to the associated cost savings and talent supply. These two advantages are closely associated, and without a CIO's leadership it is difficult to maintain. Ultimately, because of technology, organizations need to continue to learn how to manage themselves using virtual technology, which is still an immature process in most firms.

Remote communications depends on the effective use of what we call virtual teams. Virtual teams can be made up of workers anywhere, even those in the United States who are working from a distance rather than reporting to an office for work. A growing number of employees in the United States want more personal flexibility; in response, many companies are allowing employees to work from home more often—and have found the experience most productive. This type of virtual team management generally follows a hybrid model, with employees working at home most of the time but reporting to the office for critical meetings, an arrangement that dramatically helps with communication and allows management to have quality check points. However, working from home is impossible without the necessary technology to support important interactions as well as validation of work being performed.

However, the general consensus tells us that virtual teams render results. According to Bazarova and Walther, “virtual groups whose members communicate primarily or entirely via e-mail, computer conferencing, chat, or voice—has become a common feature of twenty-first century organizations.”3 Most important, we feel that the growing use of virtual teams will ultimately facilitate the complete integration of IT and non-IT workers—something that successful CIOs certainly advocate must happen for their long-term success.

Talent Management Services

Competing for the best talent is a critical objective for HR organizations. A number of firms have plans to overhaul their manual or existing systems in favor of more robust automated systems to access and track opportunities to find the best people. Indeed, Watson Wyatt, a consulting firm servicing the insurance and financial sectors, provided a survey in 2009 that found that 56 percent of the companies were planning to upgrade their systems to better technologies. These new systems will employ more advanced capabilities for integration of compensation, recruiting, performance management, learning management, career planning, and succession planning.4 The Wyatt study also found that over 50 percent of companies still used manual solutions for a number of talent management activities, such as succession planning (53 percent), career development (48 percent), and workforce planning (55 percent).

Ultimately, talent management automation is yet another strategic imperative for the support of future business growth, especially as it relates to performance efficiency. The question, of course, is why haven't HR executives implemented many of these performance improvements and why are many of them still doing it manually? The challenge stems from the historical inability for HR executives to gain support from the top. Next to the CIO, HR executives have similar challenges in that they are inevitably at the low end of the food chain for investments—HR is a supporter, and thus will always be evaluated on economies of scale and efficiency. In addition, HR has been unsuccessful in making a footprint as a strategic driver. We see HR functions becoming more of a compliance organization than a human development one. As a result, we believe that the technology executives of the future can provide more value given the need to automate and integrate talent management products throughout the enterprise. This is especially true given the widespread expansion of international personnel—pressuring firms to come up with products and services that inform employees and make them more aware and knowledgeable about the firms in which they work.

Yet another challenge for firms is the continued projections of shortfalls in talent, particularly of skilled workers. As economies rebound there will be even more pressure to find and develop the right talent. This is further complicated by the growing number of skilled labor workers that will be retiring without a formidable inventory of younger workers to replace them. Indeed, the cost of replacing employees can be astronomical.

The talent dilemma is consistent with Prahalad's theory of N = 1 and R = G. Given global expansion of the workforce, the need for “on-demand” resources (R = G) requires more integrated automation for finding and maintaining an effective and agile workforce. This workforce is not necessarily limited to employees. R = G does not specify employment resources, just resources. This means that firms will have integrated resources that include independent contractors, employees, and outside firms. It is difficult to imagine all of these requirements being solely handled by HR.

Finally, the advent of these expanded and dynamic HR talent responsibilities also feeds the need for robust reporting. These reports might include performance distribution, adherence to budgets, and exceptions. Such reporting will likely need to contain graphic displays, summary statistics, and detailed compensation data. The products must also allow for analytic capabilities to provide HR staff, managers, and executives with strategic reporting on demand.

Strategic Information

Strategic information is what we call the future of knowledge sharing in such a way that it provides strategic direction to firms. Today's popular term is data analytics, or the ability to analyze data and provide strategic information for executives and managers. Among the CIO profession the term Big Data has emerged as the key to providing business with the strategic data they need to compete. To some extent strategic information falls under the theoretical study of knowledge management. In any case, the ability to provide strategic knowledge from both internal and external sources is invaluable for today's and tomorrow's firms. The impact of strategic knowledge can improve access to learning resources, improve decision making, and establish better communication channels in general. Our interviews with successful CIOs confirmed the current importance of analytics and Big Data. However, our future predictions are that data information is only one portion of the needs of tomorrow's businesses.

Our strategic information comprises the following components:

- Data analytics and Big Data

- Knowledge management

- Restructured work processes

Data Analytics and Big Data

As stated earlier, data analytics is perhaps the most relevant area of strategic information flow, particularly at the board of directors. Data analytics is a criterion for examining data with the focus of determining conclusions using scientific evaluation. Data analytics uses deductive methods to derive conclusions based on what is known in the data, as opposed to data mining, which is the process of determining what the data mean. Another aspect of analytics study is “predictive” analytics, which is really a part of the data mining camp. It focuses on predicting probabilities and trends based on analysis of the data. Big Data, on the other hand, looks at very large sets of data (data sets)—so large that the complexity of processing is a challenge and beyond the typical capacities of relational database technologies.

Knowledge Management

Because evaluating emerging technologies requires the ability to look into the future, it also requires tomorrow's technology executives to translate valuable tacit knowledge and to see creatively how these opportunities would be judged if implemented. Tacit knowledge is defined as the processes and procedures that are not documented in an organization, that is, the knowledge exists in individual minds. Examples of applicable tacit knowledge in this process are extracted from Kulkki and Kosonen:

- Cultural and social history

- Problem-solving modes

- Orientation to risks and uncertainties

- Worldview organizing principles

- Horizons of expectations5

So the challenge to organizations is to uncover how to transfer this “tacit” knowledge into “explicit” documented knowledge. Indeed, as Teece states: “Information transfer is not knowledge transfer and information management is not knowledge management, although the former can assist the latter. Individuals and organizations can suffer from information overload.”6 While this is a significant issue for many firms, the ability to have an organization that can select, interpret, and integrate information is a very valuable part of future knowledge management. This is why knowledge management is so important. Knowledge must be built on its own terms—which requires intensive and laborious interactions among members of the organization. CIOs are the logical choice to carry out this challenge.

Restructured Work Process

Restructuring the work process entails reduction of costs while increasing service levels. Typically, these improvements are results of reengineering efforts with the aid of automation. Indeed, restructuring projects, supported by advanced technologies, have proven to be an effective tool for sustaining business competencies and improved efficiency.

We know that restructuring takes time and resources. IT has the most experience of any organization in the design and development of new systems, which often require reengineering exercises with the business. Business analysts have been making a living by working with business units and developing alternative ways to gain efficiency and cost reduction through automation. Automation represents the most obvious way to achieve such improvements. Therefore, the process of reengineering and the need for restructuring simply match each other and suggest that IT be the driver of the effort. This represents a perfect opportunity for CIOs of the future.

New Innovations

Often, new innovations have been coined disruptive in that they establish new markets and networks. Thus, it disrupts existing markets and forces new evolutions of S-curves. Disruptive innovations are often technology dynamisms that require organizations to use responsive organizational dynamism.7 Technology dynamism has shown that it can change industries overnight and likely will continue to do so.

To us, the technology executives of the future will be the most influential people in the C-suite—if, of course, they adhere to the best practices that we offered earlier, in Chapter 6. Another important area relates to the work of Henry Chesbrough,8 who pioneered the concept of “open innovation.” Chesbrough presents a model that suggests that success with new innovations is heavily predicated on staying away from closed systems, like owning intellectual property, having the best people, and trying to invent everything inside your company.9 He provides case after case showing that firms like Xerox failed to maintain their market leadership because they did not partner with outside firms and create an open framework to compete. Simply put, open innovation allows companies to be more agile and creative. It is also consistent with N = 1 and R = G—using resources from strategic alliances to ultimately place firms in an ongoing and evolutionary state. As Chesbrough states, “to successfully innovate in the twenty-first century, companies need to open up and work with external partners to commercialize internal innovations, allowing unused internal ideas to be taken to market by others externally.”9

The depth and breadth of technology-based innovations will increase dramatically over the next five years, according to Gartner's recent report. They stated that “information will be presented via new user interfaces such as organic light-emitting displays, digital paper and billboards, holographic and 3D imaging and smart fabric.”

Furthermore Gartner recommends that CIOs establish formal operations to evaluate new technologies by setting up teams which are afforded the proper time to do the research they need to support the continual evolution of innovation opportunities. Much of these innovations, as stated in Chapter 1, will be driven by consumer demand. The following are Gartner's top 10 most disruptive technologies:

This list provides examples of very advanced technologies that can have huge effects on competitive advantage—the challenge is how to bring such disruptions to the forefront of the business process. Who else but a well-prepared CIO could handle this complexity?

Security and Intelligence

The advent of the Internet, social media, and terrorism has dramatically changed the importance of security as it relates to the CIO function. Most of these security issues start with technological advances that allow individuals and groups to do things that can cause irreparable harm to organizations. These “harms” take on many complexities that start with the protection of data as well as the ways information is communicated to the consumer population. As with most security approaches, intelligence about risks is the first place to start—starting with intelligence helps determine security risks and allows organizations to put plans in place to avoid problems. Indeed, one of the regular agenda items with CIOs at board meetings is protection and security.

So, without question, security is a main concern for current CIOs. The typical issues relate to protecting the network and data files. Breaches against any of these can have great impacts on productivity as well as profitability and, most important, a firm's overall image. CIO Insight magazine recently issued a report “10 Security Concerns You'll Lose Sleep Over in 2011” that included the following:

What is interesting about these 10 top issues is the dilemma of control versus freedom. We have articulated throughout this book the movement toward consumerization, even within companies. Security tends to limit this ability and as a result will continue to be a debate among executives. Indeed, we spoke to CEOs who are beginning to believe that the days of complete security are coming to an end. Simply put, data seem to be traveling everywhere.

Furthermore, the 10 hot issues represent only a small portion of the security challenges to come. CIOs will need to step up to integrate other forms of security that logically relate to automations issues, from ID theft protection to security access across locations and production systems. Virtually every form of manufacturing will contain software of some type, which will need centralized methods of determining ongoing exposure, formulating acceptable risks, and dealing with inevitable compromising of systems. Advance security will rely on the intelligence systems around us, similar to those activities taken against terrorists by the government. There are also sophisticated technologies that will be developed that need constant evaluation, including recent concerns about cloud protections. Here, we see new approaches taken by chipmakers, firmware, architecture, and server platforms.

Business Process Integration

Business process integration (BPI) represents the ability to synchronize multiple systems in real time. The linking of systems includes internal operations as well as third-party vendors and business partners. BPI has traditionally included components such as electronic data interchange (EDI), message-oriented middleware (MoM), and enterprise application integration (EAI).

According to the Gartner Group, “Businesses that connect the design of information and business process with technology will exceed average sector performance by at least 15%.” This prediction was through 2011, and it is expected to continue. For BPI to work efficiently it must break down the barriers among businesses. In a global context, this is critical, and thus we feel that the CIO will continue to be the main implementer of such efforts. Ultimately, the framework needed for successful BPI is the integration of data. This integration requires specific activities that can address the problems with silos of automation that can exist throughout the enterprise.

These self-contained automations need to either be redone (unlikely), or bridged via reengineering to ensure that data flows among its related components of the system. Some of these data, unfortunately, in many organizations is still in manual or limited automation configuration posing major challenges to accomplishing a fully integrated solution. Another important aspect of integration is performance. It is one thing to have the architecture that allows data to be shared; it's another to accomplish this productively in a way that employees can see the difference between effort and outcome.

Automating the business process is only one major component of the challenge. Integration also requires analysis and design. This design includes “flowing dependencies,” which relate to processes that feed data to other systems. Furthermore, there are also dependencies where the output from one business unit is shared by other departments. Finally, there are dependencies where the same data are accessed by multiple departments but used for different purposes; that is, what the information means to one business unit might mean something different to another. This all translates into having personnel with the appropriate expertise to do business process reengineering (BPR). This requires a life cycle of understanding business needs, analyzing them for common architecture, and then propagating a design that caters to the organization as a whole. IT has been practicing BPR for decades and is best positioned to take on this challenge. Thus, the CIO of the future needs to expand his or her horizon and expand the IT reengineering methodology to include more expanded applications of automation and manual processes.

Ultimately, the need for reengineering through BPI requires the establishment of standards of operation and compliance—both of which are essential to create effective and efficient enterprise solutions that integrate together. Standards also feed the needs toward the goal of operational efficiency while maintaining quality and support. Standards also allows for the creation of process measures, which are required to properly analyze optimization versus quality.

Quality also heavily depends on a development methodology. BPI and the IT system development life cycle (SDLC) have remarkable similarities. BPI uses a five-stage process: analyze, identify, simulate, validate, and deploy. The IT SDLC matches are analysis, design, prototype, test, and go live. We know that restructuring takes time and resources. IT has the most experience simply because it already has the core skills sets to expand BPI operations. Systems analysts make a living by working with operating units to determine how best to use automation to improve performance of their departments while reducing labor costs.

The process of reengineering and restructuring simply matches the future challenges of redistribution of labor across global markets. Looking at this process, it seems favorable for today's CIO to very well be ready for tomorrow's challenges of BPI.

Mobility

Perhaps mobility is the largest challenge for firms today, not to mention the future. The dilemma is how to support the consumerization of technology through smartphones and tablets, yet at the same time protect firms from the problems they create. The most salient supporter of mobility has been the advent of cloud technology. Indeed, cloud automation has allowed for the access of applications, data, and videos from anywhere on a mobile device. The continual acceleration of change across mobile units will be staggering—that is, the S-curve of mobility may have shorter and shorter life cycles. This all means that decisions and strategies regarding mobility will need to be rethought almost on a regular basis.

Indeed, the risks associated with mobile technologies opens up major potential threats to firms. A Veracode blog recently issued a number of vulnerabilities:

- Sensitive data leakage. Disclosing user location and personal information resident on the mobile device.

- Unsafe sensitive data storage. This includes passwords and other key information that needs to be encrypted.

- Unsafe sensitive data transmission. Mobile devices are accessible to eavesdroppers during user communications.

- Hardcoded password/keys. This information can be unencrypted by certain applications.

What is interesting about mobile threats is the dilemma of control versus freedom. We have articulated throughout this book the movement toward consumerization of technology. Security tends to limit this ability and, as a result, will continue to be a debate inside many firms. Indeed, we spoke recently to a CEO who now believes that the days of security may be coming to an end. Data seem to travel everywhere!

Organizations need to realize that mobility has penetrated much faster than the Internet. Gartner predicts that mobile phones will overtake PCs as the most common Web access device by 2013. Furthermore, Gartner estimates that by 2014, three billion of the world's adult population will be able to conduct transactions via mobile devices or Internet technology. And, by 2015, context (location, presence, and social interactions) will be as important to consumer services as search engines are to the Web. Thus, using mobility provides significant access to the world. Its impact on advertising alone is significant for publishers, operators, network agencies, and advertisers. However, most firms have challenges, including:

- Lack of appropriate policies.

- Proliferation of mobile devices without the ability to account for them properly.

- Increased risks of unauthorized exposure of sensitive information.

It appears again that the CIO is well positioned to deal with the proliferation of mobile devices and the forecast of growth of mobility in general. Most important is the need that future automation executives have to deal with the risks and rewards of mobility and the ongoing challenge of the rewards versus the risks.

Conclusion

This chapter has attempted to predict the roles and responsibilities of future technology leaders. Many have focused their predictions on the title of the new CIOs of the future. These new titles and responsibilities often suggest that the CIO role be cut up into pieces. Some of these suggestions include:

- Chief technology officer. This role exists usually under the CIO, but many feel that the CTO should be a peer of the CIO and handle the technical issues of the IT department. In some companies, there is only a CTO—this exists in technology-driven firms.

- Chief integration officer. An interesting title and defined as someone who integrates technology with business applications.

- Chief data scientist. Leaders who focus on the meanings of the data, suggesting that data analytics and knowledge management are the most important aspects for business technology use.

- Chief innovation officer. This looks at the role as a driver only and focuses on new inventions and uses of technology.

- Chief administrative officer. This looks at the role as a chief operating officer without the financial responsibilities.

The problem with these titles and responsibilities is that no one of them encompasses the total responsibilities we have articulated in this chapter. Figure 8.1 graphically represents the myriad of total responsibilities of the role as we see it developing.

Figure 8.1 Responsibilities of the Non-IT CIO

Source: “Adapting to the Data Explosion: Ensuring Justice for All.” IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, San Antonio, Texas, October 11–14, 2009.

We have advocated a title of chief of automation, but the question to be addressed is whether it really matters. The most important thing about the future leaders of automation and technology is in what they do and perform for their firms. We used automation because we feel strongly that the role needs to better align itself with the business and technology as opposed to the traditional IT department. We suggest that CIOs reinvent themselves as true C-level leaders and seek to bring value based on the needs of the entire business. Automation seems to embrace the entire realm of issues that we discussed, as well as those that have yet to be developed. However, it is our vision that the challenge of the CIO will remain as a role that continually looks at manual transactions and evaluates whether automating them will bring efficiency and drive new business. We also feel that it is important not to reduce the importance of the supporter side of the CIO. Just because the support role of the CIO does not directly drive strategy, it does not mean it is not significant, especially for reducing costs and improving efficiency. To be specific, driver strategies will never start out as being efficient or cost saving. Many of the responsibilities outlined in Figure 8.1 are indeed supporter responsibilities, which is why we stick to our feeling that the role is best described as an automation leader.

Another question often asked at CIO conferences is whether CIOs can become CEOs. We believe that the chief automation officer can become the CEO, simply because of the enormity and range of their responsibilities. The road to the CEO, in many firms, has traditionally been through sales and marketing simply because these individuals drive revenue. Figure 8.1 shows the amount of new business being driven by automation, so we believe that automation officers may be better suited for the CEO-level responsibilities to drive revenue using a myriad of diverse ways. In other companies, the CFO has been the road to the CEO position. Again looking at the operational responsibilities of an automation officer, we see equal levels of knowledge to handle the CEO function. This is why we titled this chapter “The Non-IT CIO of the Future.”

Notes

1 Joel Schectman, “New EU Privacy Rules Put CIOs in Compliance Roles,” Wall Street CIO Journal (June 7, 2012).

2 “Adapting to the Data Explosion: Ensuring Justice for All,” in Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (2009).

3 N. N. Bazarova and J. B. Walther, “Attribution of Blame in Virtual Groups,” In P. Lutgen-Sandvik and B. Davenport-Sypher (Eds.), The Destructive Side of Organizational Communication: Processes, Consequences, and Constructive Ways of Organizing (Mahwah, NJ: Routledge/LEA, 2009), 252–266.

4 Carrie Burns, “Automated Talent Management,” Information Management (2009), www.information-management.com/news/technology_development_talent_management-10016009-1.html.

5 S. Kulkki and M. Kosonen, “How Tacit Knowledge Explains Organizational Renewal and Growth: The Case at Nokia.” In I. Nonaka and D. Teece (Eds.), Managing Industrial Knowledge: Creation, Transfer and Utilization (London: Sage, 2001), 244–269.

6 D. J. Teece, “Strategies for Managing Knowledge Assets: The Role of Firm Structure and Industrial Context.” In Nonaka and Teece (Eds.), Managing Industrial Knowledge, 125–144.

7 A. M. Langer, “Responsive Organizational Dynamism: Managing Technology Life Cycles Using Reflective Practice,” Current Issues in Technology Management 9(2) (2005): 1–8.

8 H. Chesbrough, Open Services Innovation (San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass, 2011).

9 Ibid.

10 Don Reisinger, “10 Security Concerns You'll Lose Sleep Over in 2011,” CIO Insight, January 5, 2011.