6. Essential Photoshop Tips and Tricks

The biggest speed boost you can give to Adobe Photoshop is to accelerate your own productivity. If you get paid by the hour, rather than by the amount of work accomplished, you may want to skip this chapter. If you want to realize the full potential of Photoshop as a lean, mean, pixel-processing machine, read on! You’ll learn how to break the habit of choosing tools by clicking on their icons, and avoid those lengthy mouse voyages up to the menu bar.

If you’re upgrading from Photoshop CS3 or earlier, you’ll want to review this chapter because you may be encountering, for the first time, the sweeping revisions Adobe made to the user interface back in Photoshop CS4. Many of the changes were made possible because Photoshop now gets help from the graphics processing unit (GPU) on your video card to take a load off of the central processing unit (CPU). Photoshop uses the GPU to drive many of the navigation tips that have been added since Photoshop CS4, such as smooth interactive zooming. You can review video card requirements in Chapter 1.

Window Tips

As applications pile up on the panels and options, screen space remains at a premium even as monitor sizes grow. Space is an even bigger challenge if you need to manage multiple windows. Photoshop gives you choices here.

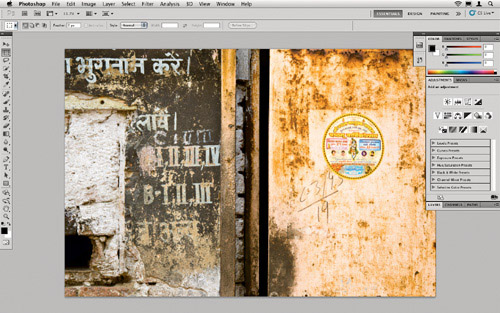

Use Screen Modes or the Application Frame. Press F to cycle through the available screen modes (see Figures 6-1 to 6-3). You can also pick a screen mode from the Screen Mode submenu (under the View menu) or click and hold the Screen Mode icon in the Options bar. Pressing F is so easy that you’ll probably go to the View menu only if you’re recording an action that plays back a screen mode change.

Figure 6-1 Standard screen mode while clicking the Screen Mode button on the Options bar

Figure 6-2 Full Screen with Menu Bar screen mode (and Mac OS X dock hidden)

Figure 6-3 Full Screen mode; panels are hidden by default but tools are still accessible using shortcuts

When Windows Photoshop users switch to the Mac, many find it distracting to see the desktop picture and other programs behind their Photoshop windows and panels. To remove this distraction on the Mac, choose Window > Application Frame (see Figure 6-4) to put all Photoshop windows and panels inside a sort of master window with a gray background. While it’s common to fill the whole screen with the application frame, the example shows that the application frame can be made smaller than the screen so that you can have the best of both worlds: a solid gray background for Photoshop while still being able to interact with the desktop for operations such as drag and drop (you can’t easily do that with the Full Screen modes).

Figure 6-4 The application frame almost but not quite maximized, to allow drag and drop with other programs

Note

![]()

Some Mac users perceive the application frame concept as un-Mac-like, but iPhoto, iDVD, and other Apple programs use a similar application background.

If you’re a strict Mac traditionalist, don’t worry; the application frame is turned off by default on the Mac. One good reason to use the application frame is to use the n-up view to quickly arrange documents in panes, as described later in this section. When the application frame is off, n-up views use regular floating windows, which are harder to keep arranged.

Change the Surrounding Color and Border. All screen modes surround the document with gray except for Full Screen mode, which is black. To change the color, Control-click (Mac) or right-click the surrounding area and choose an option from the context menu that appears. You can also change these colors in the Color section of the Interface tab of the Preferences dialog. (You can’t change the application frame background color.) Next to the Color section is the Border section, where you can specify whether the image edge should be a line or a drop shadow. You can also get rid of the border altogether, which I prefer to do.

Tip

![]()

If you hide the Application bar and its controls for tabbed windows and n-up windows, you can still manage them using the Window > Arrange submenu.

Multiple Views of the Same Document. Are you often jumping back and forth between two views? For example, between different magnifications, color modes, or preview modes? If so, consider opening a second window by selecting Window > Arrange > New Window and setting it to the alternative view. Whenever you change something in one window, Photoshop updates the other window right away.

Tidy Up Your Windows. Photoshop offers tabbed and n-up windows to add to the traditional Cascade and Tile commands. When you have many windows open, these options can get your workspace organized quickly.

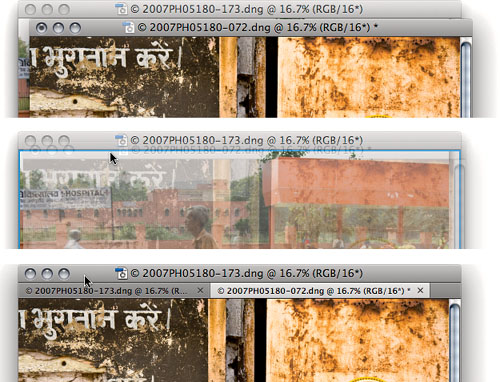

• Tabbed windows. If you’ve used tabs in your Web browser, you already know how this works. Instead of having to manage many windows, you collect them into a single window with a tab for each document. To combine windows into tabs, just drag one window’s title bar to another window’s title bar until you see a thick blue border at the bottom of the destination window, then release the mouse (see Figure 6-5). You can pull them apart in the same way. If you have many windows to tab together or many tabs to pull apart, choose Arrange > Consolidate Windows into Tabs or Arrange > Float All in Windows, respectively. You might find it faster to manage these windows through the Arrange Documents button on the Application bar. You can even have tabs within multiple floating windows—handy for multiple monitors.

Figure 6-5 Drag one document’s title bar to another title bar and release the mouse button when you see a blue border. The first document becomes a tab in the second document window.

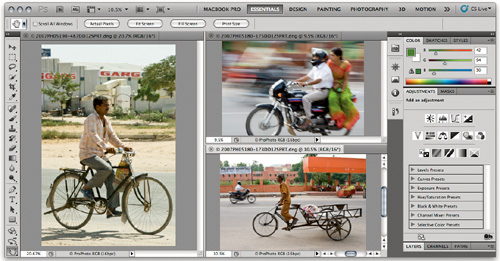

• N-up windows. N-up refers to a view that displays multiple documents side by side, such as 3-up or 8-up views (see Figure 6-6). For example, in a 3-up view, three documents appear as three panes in one window. N-up views are often faster than arranging windows by hand.

Figure 6-6 The Arrange Documents button in the Application bar lets you create n-up views quickly, such as this 3-up view.

Tip

![]()

Tabs are useful when you want to have multiple documents open yet give each individual image maximum area, while n-up display is useful for quickly arranging documents for comparison, or for dragging and dropping content between documents.

To use a preset n-up view, select one of the n-up icons from the Arrange Documents icon menu in the Application bar. In Mac OS X, if the application frame is off, the documents are arranged as floating windows instead of tabbed panes.

To manually create paned n-up views, drag a document title bar or tab to any edge of any document; when you see a blue border, release the mouse. (In Mac OS X, the target document must be in an application frame.) You can have multiple tabs within any pane in an n-up view, freely combining the two options. In addition, you can use floating windows along with the application frame.

Tip

![]()

If it takes too long to cycle to a specific document using the keyboard, it may be faster to choose the name of the document from the Window menu.

Flip Through Windows or Tabs. Use your operating system’s standard keyboard shortcut to cycle quickly through the open Photoshop windows and tabs—press Command-~ (tilde) in Mac OS X or Ctrl-Tab in Windows. This way you can cycle through every tab in every window without touching the mouse. Add the Shift key to cycle in the opposite order.

Tip

![]()

If your non-English Mac keyboard has no tilde key, the old Control-Tab shortcut still works for flipping through open windows.

From a Document to Its Folder. In Mac OS X, open the folder that contains a saved document by Command-clicking the filename in the document window’s title bar and selecting the folder from the pop-up menu that appears. This tells Photoshop to switch to the desktop and open that folder. In Windows, you can reveal a document’s file system path by holding the mouse over a document’s title bar until a tool tip appears.

Note

![]()

Revealing folder paths in Mac OS X works only for saved documents in floating windows, not in tabs.

Navigation Tips

Read this section even if you think you know all there is to know about navigating Photoshop—especially if you upgraded from a version that doesn’t have the GPU-accelerated navigation features that first appeared in Photoshop CS4. Even expert users might pick up a tip or two here.

Zooming Tips

Images have pixels. Computer monitors have pixels. But how does one type of pixel relate to the other? When one image pixel is displayed on one monitor pixel, you’re seeing every detail of the image. In Photoshop, this happens at 100 percent magnification, or the View > Actual Pixels command. This view doesn’t necessarily tell you how big the image will appear in print or even on the Web, because different monitors have different resolutions.

At 400 percent, the image is magnified four times, so each image pixel is displayed using 16 monitor pixels (see Figure 6-7). At 50 percent, you’re seeing only one-quarter of the pixels in the image, because zooming out causes Photoshop to downsample four image pixels to one monitor pixel. At percentages other than 100, then, you’re not seeing an accurate view of your image because you aren’t seeing the exact number of pixels in the image.

Figure 6-7 How magnification affects the image detail you see

![]()

When you’re viewing at an integral multiple of 100 (such as 25, 50, 200, or 400 percent), Photoshop displays image pixels evenly. At 200 percent, four screen pixels (two horizontal, two vertical) equal one image pixel; at 50 percent, four image pixels equal one screen pixel, and so on. However, at magnifications that aren’t a factor of two, Photoshop can’t cut a screen pixel or an image pixel in half, so instead it fakes the effect using anti-aliasing.

Magnifications other than Actual Pixels (100 percent) can give you a distorted view of resolution-dependent effects such as sharpening. Use Actual Pixels magnification to see your image most accurately. You’ll be doing this all the time, so learn the shortcuts: Command-Option-0 (zero) (Mac) or Ctrl-Alt-0 (Windows), or double-click the Zoom tool in the Tools panel.

Quick Access to the Zoom Tool. I don’t select the Zoom tool from the Tool panel—there are easier, faster ways to zoom. You can temporarily switch to the Zoom tool by holding down Command-spacebar to zoom in or Command-Option-spacebar to zoom out (Mac), or Ctrl-spacebar to zoom in or Ctrl-Alt-spacebar to zoom out (Windows). Each click is the same as choosing Zoom In or Zoom Out from the View menu.

Note

![]()

Zooming doesn’t extend the document under the edges of panels unless you’re in one of the Full Screen modes.

Zoom Precisely and Naturally. If you’re new to Photoshop, or you’re used to older versions, you might have the habit of zooming in to an area by clicking over and over again until you hit the right magnification and location. That works, but Photoshop CS5 gives you more interactive ways to zoom.

• Scrubby zoom. Position the Zoom tool over the area you want to magnify and drag to the right; the area you drag magnifies continuously. Drag left to zoom out. If you used the old way of dragging a zoom rectangle to magnify, this new way might throw you off at first!

Note

![]()

The interactive zooming features require an OpenGL video card that meets the specifications described in Chapter 1, “Building a Photoshop System.”

• Animated zoom. Position the Zoom tool over the spot you want to magnify and hold down the mouse button until you reach the magnification level you want. You can turn this off by deselecting the Use Gestures option in the Interface panel of the Preferences dialog.

• Pinch gesture zoom. If you use a Mac multitouch trackpad, you can zoom by using the two-finger pinch gesture in Mac OS X. You can turn this off by deselecting the Use Gestures option in the Interface panel of the Preferences dialog.

WIth any of those methods, you can zoom out by also pressing the Option key (Mac OS X) or Alt (Windows) key.

Zoom with Keyboard Shortcuts. Zoom in and out by pressing Command-+ (plus sign) or Command- − (minus sign) in Mac OS X, or by pressing Ctrl-+ (plus sign) or Ctrl- − (minus sign) in Windows. By default in Mac OS X, a window resizes when you zoom it; it doesn’t resize in Windows by default. If you prefer the opposite behavior, toggle the Zoom Resizes Windows check box in the General Preferences dialog.

Zoom with the Scroll Wheel. If your mouse has a scroll wheel, you can use it to scroll or zoom. To switch between scrolling and zooming, press Option (Mac) or Alt (Windows). To set the default behavior, toggle the Zoom with Scroll Wheel check box in the General Preferences dialog.

Fit the Image Within the Window. Double-clicking on the Hand tool is the same as clicking Fit Screen in the Options bar when the Zoom tool or Hand tool is selected, or pressing Command-0 (zero) (Mac) or Ctrl-0 (Windows)—it makes the image and the document window as large as possible without going outside the screen’s boundaries. The image may not zoom to the full width or height of the monitor if panels are present.

Zoom Numerically. At the bottom-left corner of the document window or Navigator panel is the current magnification percentage. This isn’t just a display: Double-click to select the whole field, type the zoom percentage you want, then press Return or Enter (see Figure 6-8).

Tip

![]()

The preset magnifications on the View menu, such as Print Size, are also present as buttons on the Options bar when the Zoom tool is selected.

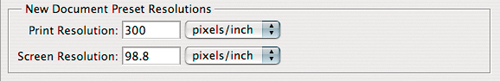

Calibrate the Print Size Command. Generations of Photoshop users have been baffled by the View > Print Size command, because it never seems to match the size of the image when they actually print! In fact, there is a way to make it work. The only way the Print Size command can know the actual print size is to know the resolution of your monitor so that the rulers become accurate. To make Print Size work right, do the following:

1. Open the Displays system preferences pane (Mac) or the Displays control panel (Windows), and note your monitor’s current resolution setting (for example, 1280 × 854 pixels).

2. Grab an actual, real-world ruler and measure the width of your monitor image (not the frame in inches). Be careful not to scratch your screen!

3. Divide the horizontal pixel dimension of your monitor by the horizontal real-world dimension of your monitor. For example, my wide-screen LCD monitor is set to 1680 pixels across a physical width of 17 inches, and 1680/17 = 98.8 pixels per inch.

4. Open the Preferences dialog, click Units and Rulers, and enter your pixels per inch value into the Screen Resolution field (see Figure 6-9).

Figure 6-9 Setting the screen resolution for accurate Print Size

Now when you choose View > Print Size, Photoshop can take into account both your screen resolution and the resolution of the image in the Image > Image Size dialog, and correctly display the printed size of the image. Another wonderful result of all this is that your rulers now match the real world at Print Size magnification. If the rulers don’t match exactly, adjust the Screen Resolution field slightly until they do.

Sync Up Your Windows. When you’re working in multiple windows, it’s often helpful to sync up their views. Several commands on the Window > Arrange submenu automate this process. Match Zoom synchronizes the zoom level, Location synchronizes the positions of images in windows, and the Rotation command synchronizes the rotated views (more on that soon). The Match All command applies all of the Match commands at once.

Tip

![]()

After you match up windows, you can zoom or move them together using the Shift key tip below.

Moving the View

If you’re like most Photoshop users, you find yourself moving the image around a lot. There are much better ways than using the window scroll bars, which are so 20th century that I hardly use them anymore.

Tip

![]()

To use the Zoom or Hand tool on every open image window at the same time, hold down the Shift key as you click the Zoom tool or drag the Hand tool. The Options bar includes a Zoom All Windows or Move All Windows check box if you don’t want to hold down the Shift key.

Fast Window Panning. In addition to the traditional ways to push an image around the screen, Photoshop gives you GPU-assisted window navigation features such as the following:

• The Hand tool. Hold down the spacebar (to get the Hand tool) and drag. In Full Screen mode, use the Hand tool to slide past the edge of the image into the gray or black area, no matter how far you’re zoomed in; going past the edge is something scroll bars can’t do. Scrolling past the image edge is useful when you’re cropping or retouching close to the edge of an image.

Tip

![]()

I don’t cover the Navigator panel because the newer bird’s-eye view and interactive zooming features are now more convenient.

• Flick panning. If you’ve ever “tossed” an image across the screen on an iPhone or in Google Earth, you already know this gesture: Drag quickly and release the mouse button before you stop dragging. The image continues moving across the screen, slowing to a stop. If you don’t like this behavior, turn off Enable Flick Panning in the General pane of the Preferences dialog. Flick panning doesn’t help much for short moves, but it does save effort in a very large image such as a panorama.

Note

![]()

Flick panning and bird’s-eye view require a video card that meets the specifications described in Chapter 1.

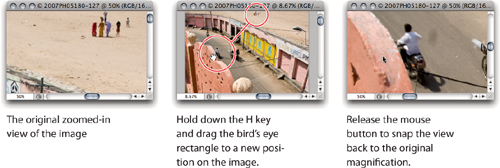

• Bird’s-eye view. Hold down the H key and drag; this temporarily zooms out a magnified view and displays a rectangle that represents the part of the image that fits the window at the current magnification. Drag the rectangle to another area of the document and release the mouse button to restore the original magnification at the new area (see Figure 6-10). If the document is smaller than its window, the same gesture zooms to fill the window. This is much cooler to try than to read about!

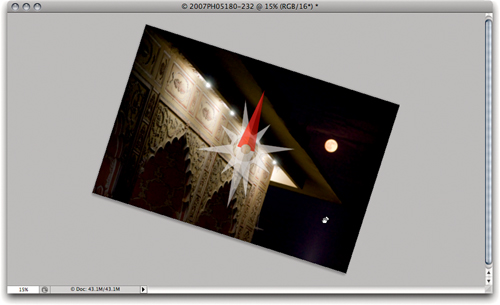

• View rotation. Don’t confuse view rotation with image rotation. When you rotate the image, it’s altered permanently. View rotation changes only the screen display, similar to view magnification. To rotate the view, select the Rotate View tool (press R) and drag it; you’ll see a compass icon in the middle of the window (see Figure 6-11) as well as view rotation options in the Options bar.

Figure 6-11 View rotation with compass indicator; red points to the original top edge

Tip

![]()

Rotating the view can be useful when working on a document with upside-down text (as in a card to be folded over) or when you’re painting or retouching with a tablet.

If you use a Mac multitouch trackpad, you can use the Mac OS X two-finger rotation gesture. If you don’t like this feature because you keep setting it off by accident, you can turn it off by deselecting the Use Gestures option in the Interface panel of the Preferences dialog.

End Up Down Home. Many people ignore the very helpful Page Up, Page Down, Home, and End keys when working in Photoshop, but they’re invaluable for perusing an image for dust spots or other defects.

Tip

![]()

If you’re on a laptop, the Page Up, Page Down, Home, and End key functions may be overlaid with the arrow keys. For example, to use Page Up on a Mac, add the Fn key at the bottom-left corner of the keyboard, so that you press Fn–up arrow to get Page Up.

When you press Page Up or Page Down, Photoshop scrolls the image by one whole window of pixels up or down. Although there’s no Page Left or Page Right button, you can jump one window of pixels to the left or right by pressing Command-Page Up or Command-Page Down in Mac OS X, or Ctrl-Page Up or Ctrl-Page Down in Windows. You can scroll in 10-pixel increments by adding the Shift key to any of these shortcuts. Bonus: Pressing the Home button jumps you to the top-left corner of the document, and the End button jumps you to the bottom-right corner.

Context-Sensitive Menus. When you right-click or Control-click (Mac), Photoshop displays a context-sensitive menu that changes depending on the tool you have selected in the Tool panel. Context menus are so accessible that they’re worth trying out with any tool you use (see Figure 6-12).

Figure 6-12 The context menu for the Move tool, displaying available layers under the cursor

Tip

![]()

The Home and End keys are very useful for closely checking the top-left and bottom-right corners of the Crop tool.

For brush or retouching tools, the context menu is a quick way to customize the brush. The context menu for the Move tool lets you quickly select a layer without having to see the Layers panel, saving a lot of time in documents with many layers. If the Move tool isn’t selected, you can almost always get its context menu by Command-Control-clicking in Mac OS X or Ctrl-right-clicking in Windows.

The context-sensitive menu for the Marquee tool contains a mishmash of features, including Delete Layer, Duplicate Layer, Load Selection, Reselect, Color Range, and Group into New Smart Object. Many of these features lack keyboard shortcuts, so the context menu is the fastest way to get to them.

Moving Tips

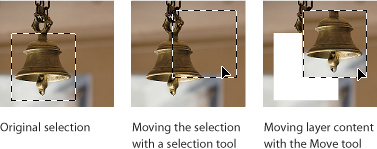

In Photoshop, more than one type of move may be available at any one time. For instance, if you’ve selected an area on a layer, you can move either the selection boundary or the selected content (such as pixels) (see Figure 6-13). Your choice will dictate which tool or keyboard shortcut you use.

Figure 6-13 Moving a selection versus moving layer content

If you simply make a selection and then drag it with one of the selection tools, you move the selection boundary but not the selected layer content. If you want to move the content, use the Move tool (press M). When another tool is selected, you can always get the Move tool temporarily by holding down the Command (Mac) or Ctrl (Windows) key. You can also use the Move tool temporarily by holding down the V key and then releasing it when you are done. (Note that if you want to move a path or shape, use the Path Selection or Direct Selection tool instead.)

Tip

![]()

With the Move or Path Selection tool, you don’t have to worry about positioning the mouse before you drag—just drag anywhere within the document window.

When you move or copy selected pixels with the Move tool, you get a floating selection, which is like a temporary layer that disappears when you deselect. While the selection is still floating, you can use the Edit > Fade command to control how it blends in with the underlying layer.

These selection tips don’t apply only to selected pixels. They’ll also work on objects like a selected path, a type layer, or the currently selected layer or layer mask in the Layers panel. Most of the tips also work on the selection boundary itself if you choose Edit > Transform Selection first.

Move Precisely. If it’s hard to keep your hand steady when working precisely, try using the arrow keys and the Options bar instead of the mouse.

Tip

![]()

If you want to move an entire layer and the layer is already selected in the Layers panel, just drag the Move tool to drag the entire layer right away without any additional selection.

With the Move tool selected, each press of an arrow key moves the layer or selection by 1 pixel. To move 10 pixels, add the Shift key. Modifier keys work, too: Hold down the Option key (Mac) or Alt key (Windows) when you first press an arrow key to duplicate, float, and move the selection 1 pixel (don’t keep holding down the Option/Alt key after that unless you want a lot of duplicates). You can always get the Move tool temporarily by adding the Command key (Mac) or Ctrl key (Windows) to any of these shortcuts.

To move an object or layer by entering x and y coordinates, choose Edit > Free Transform. (If you’re moving the selection boundary, choose Select > Transform Selection instead.) In the Options bar, enter new coordinates.

Move Multiple Layers. To move multiple layers, select more than one layer in the Layers panel and then drag the Move tool. If you haven’t selected multiple layers before, it’s just like selecting multiple files in a folder on your desktop: Shift-select the first and last layers that you want; or to select a discontiguous range, Command-click (Mac) or Ctrl-click (Windows) each layer you want to add to the selection.

Tip

![]()

Is a selection snapping to an edge, and you don’t want it to snap? As you drag, press the Control key to temporarily override snap behavior.

Drag and Drop Selections and Layers. To move selected pixels (or a layer) from one document to another, drag it from one window into the other (if you’ve got a selection, remember to use the Move tool or you’ll just move the selection boundary itself). If you’re trying to copy an entire layer, click its thumbnail in the Layers panel and drag it to the other document’s window. Either way, if you want to drop the selection smack in the exact center of the destination document, Shift-drag instead.

Tip

![]()

Dragging requires less memory than copying and pasting.

Copy Pixels. If you select pixels and choose Edit > Copy, you get only the pixels on the currently active layer(s) (the one(s) selected on the Layers panel). To copy selected pixels across all visible layers, select Copy Merged instead (Command-Shift-C in Mac OS X, Ctrl-Shift-C in Windows).

Tip

![]()

To drag a layer to another tab, drag from the document window (not the Layers panel) and hold the mouse over the other tab for a moment until it switches over.

Some people use this technique to make a merged copy of the entire image (not of just a selection). It works, but it’s actually more efficient to choose Layer > Duplicate Layers and then choose New from the Destination pop-up menu to merge all layers and send them to a new document in one step. If you’re just trying to turn selected pixels into a new layer, press Command-J (Mac OS X) or Ctrl-J (Windows), the shortcut for Layer > New > Layer via Copy—it’s more efficient than copying and pasting.

Paste Pixels. In the most common color modes, such as RGB and CMYK, pasting pixels into a document automatically creates a new layer. When a selection is active, you’ll also see the Edit > Paste Into command (Command-Shift-V in Mac OS X, or Ctrl-Shift-V in Windows), which adds a new layer with a layer mask based on the selection so that the pixels you’re pasting appear only inside the selection. If you add the Shift key to the Paste Into keyboard shortcut, the pixels you’re pasting appear only outside the selection, because adding Shift inverts the layer mask that’s created.

Tip

![]()

Making a selection and using the Paste Into command (or the Paste Outside feature that you get by adding the Shift key) lets you create both a layer and a layer mask in one step.

Guide and Grid Viewing Tips

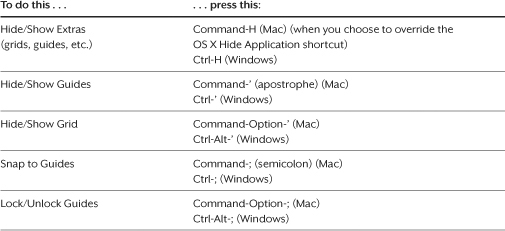

The ruler, guides, and grid are useful for marking important measurements, such as when you’re composing an image for a client’s specific layout or just trying to figure out whether your horizon is straight. Table 6-1 lists a number of grids and guides keystrokes.

Table 6-1 Grids and guides keystrokes.

Tip

![]()

You can position guides out on the area surrounding the canvas. This is useful when you want to extend layer content beyond the edge of an image.

Tip

![]()

To make a guide snap to ruler tick marks, hold down the Shift key as you drag a guide out of a ruler.

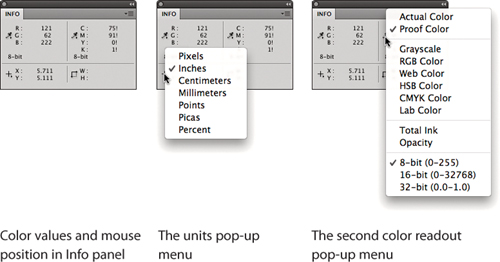

You can hide or show the ruler by pressing Command-R (Mac) or Ctrl-R (Windows). Wherever you move your cursor, you can track its position using the tick marks that appear in the rulers (or the coordinates on the Info panel). You can add a guide to a page by dragging it out from either the horizontal or vertical ruler. Or if you care about specific placement, you can watch the ruler tick marks or the Info panel coordinates, or select View > New Guide so you can type in a numeric position. (If you don’t think in inches, you can change the default measurement system; see “Switch Units,” later in this chapter.)

Dialog Tips

Dialogs seem pretty simple, but since you probably spend much of your time in Photoshop looking at them, wouldn’t it be great to be more efficient while you’re there? Here are a bunch of tips that will let you fly through them.

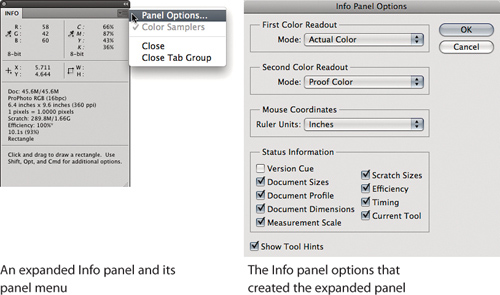

Not-So-Modal Dialogs. In Photoshop, just because a dialog is open doesn’t mean you can’t do anything else. For instance, when the Smart Sharpen dialog is open you can still scroll and zoom the document. You can also use any command that isn’t dimmed, particularly commands on the Window menu. The panel I end up opening most often from inside dialogs is the Info panel, because it displays readouts of color values.

Scrub-a-Dub-Dub. You can edit values in dialogs by scrubbing, or dragging horizontally over a value. For example, if you’re in the Image Size dialog, hold down Command (Mac) or Ctrl (Windows) as you position the mouse over any number field. When the cursor appears as a finger with a two-headed horizontal arrow, you can drag left to lower the value, or drag right to raise the value (see Figure 6-14). This also works in panels that have number fields, including the Options bar. For faster scrubbing, hold down the Shift key, which multiplies the normal adjustment by ten.

![]()

Save Your Settings. Many dialogs have Save and Load buttons that let you save to disk all the settings that you’ve made in a dialog. They’re particularly useful when you want to use the same dialog settings on many images.

Tip

![]()

In panels, such as the Adjustments panel, you might not see Load and Save buttons. Instead, look for Load Preset and Save Preset commands in the panel menu.

For instance, let’s say you’re adjusting an image with Shadows/Highlights. You increase this and decrease that, and after you click OK you realize that you’d like to apply the same settings to 50 other images shot under the same conditions. Instead of laboriously entering the same settings 50 times, just click the Save button in the Shadows/Highlights dialog to save the settings as a file. Now you can open the Shadows/Highlights dialog in any other image, click the Load button, and select the settings file you saved. This is useful when you build actions that automate your workflow, because you can have an action load a settings file. You can also send settings files to your colleagues so they can load them.

Instant Replay. There’s one other way to undo and still save any tonal-adjustment settings you’ve made. If you hold down Option (Mac) or Alt (Windows) while selecting a command from the Image > Adjust submenu, the dialog opens with the last-used settings. Similarly, you can add the Option/Alt key to the adjustment’s keyboard shortcut. For instance, in Mac OS X, Command-L is the shortcut for Levels, so Command-Option-L opens the Levels dialog with the same settings you last used. This is a great way to specify the same Levels or Curves (or Hue/Saturation, or any other adjustment) for several different images.

Previewing in Dialogs

Most of the tonal- and color-correction features and many filters offer a Preview check box in their dialogs. Plus, most filters that have a dialog include a proxy window that shows the effect applied to a small section of the image (some dialogs have both). If you’re working on a very large file on a relatively slow machine, and the filter you’re using has a proxy window, you might want to turn off the Preview check box so that Photoshop doesn’t slow down by drawing the screen while you’re making adjustments. Thanks to today’s powerful hardware, it’s practical to leave the Preview feature on.

Use the Preview check box to do before-and-after comparisons without leaving the dialog. Press the P key shortcut to toggle the Preview check box.

Note

![]()

The P key Preview check box shortcut doesn’t work in some dialogs.

Most of the tips that follow usually don’t apply to the dialogs for creative filters such as Dry Brush and Plastic Wrap. They use a different dialog that provides a large preview image inside the dialog but not in the main window. This book doesn’t cover those filters because they’re more about special effects, and this book’s more about image correction.

Proxies. The proxy in dialogs shows only a small part of the image, but it updates almost instantly. Previewing time-consuming filters such as Smart Sharpen or Reduce Noise on a large file can take a long time.

Before and After in Proxies. In most proxies, you can see a before-and-after comparison by clicking in the proxy. Hold down the mouse button inside the proxy window to see the image before the filter is applied, and release it to see the image after the filter is applied. This is obviously quicker than redrawing the whole window with the Preview check box.

Note

![]()

A proxy shows only the layer you’re working on at any one time, because a dialog affects only the current layer.

Change the Proxy View. To see a different part of the image, click and drag in the proxy (no modifier keys are necessary) or click in the document itself. Where you click becomes the detail area shown in the Preview window.

You can zoom the proxy in and out by clicking the little (+) and (-) buttons. Much faster is to click the proxy while pressing the Command (Mac) or Ctrl (Windows) key to zoom in, or the Option (Mac) or Alt (Windows) key to zoom out. However, you see the true effect of a filter only at 100 percent view.

Keyboard Shortcuts in Dialogs

I love keyboard shortcuts. They make everything go much faster, or at least they make me feel like I’m working faster. Here are a few shortcuts that I use all the time inside dialogs.

Option/Alt. Hold down the Option (Mac) or Alt (Windows) key in a dialog to change the Cancel button to a Reset button, letting you reset the dialog to its original state (the way it was when you first opened it).

Tip

![]()

Camera Raw is a dialog that allows more than one step of undo if you also press Option/Alt, or more than one step of redo if you also press Shift.

Command-Z/Ctrl-Z. You already know the shortcut Command-Z (Mac) or Ctrl-Z (Windows) because it’s gotten you out of more jams than you care to think about. You can use the same shortcut to undo within most dialogs, too. Inside dialogs, you get only one undo step.

Arrow Keys. When a dialog contains a number field, you can change those numbers by pressing the up or down arrow key. Press once, and the number increases or decreases by 1. If you hold down the Shift key while pressing the arrow key, the number changes by 10. (Note that some dialog values change by a tenth or even a hundredth; when you hold down Shift, they change by 10 times as much.) This is a great way to fine-tune adjustments without cramping your mouse hand.

Note

![]()

A few dialogs use the arrow keys in a different way. In the Lens Flare filter, for instance, they move the position of the effect.

Tab Key. As in most Mac and Windows applications, the Tab key selects the next text field in dialogs with multiple text fields. Press Shift-Tab to move to the previous field instead.

P for Preview. As was mentioned a little earlier, press P to toggle the Preview check box in any dialog that has one.

New Document Tips

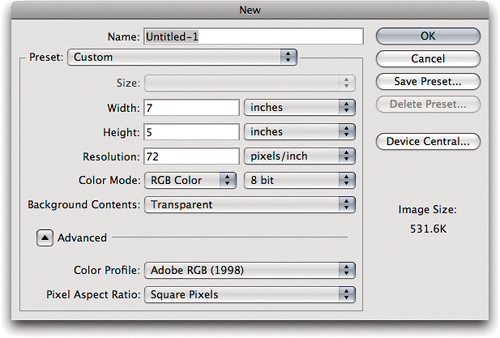

Before moving on to essential tips about tools, let’s take a quick look at the New dialog. How you start a new document affects what you’ll be able to do with it later, so it’s a good idea to familiarize yourself with the options.

Preset Document Sizes. The Preset pop-up menu in the New dialog lets you pick from among common document sizes. You may not see very many choices if you click the Preset pop-up menu, but that’s because it’s a two-stage process: First choose a category from the Preset pop-up menu, and then choose a size from the Size pop-up menu. If you need a preset other than the ones on the list, just set the New dialog the way you want it, then click the Save Preset button (see Figure 6-15). You can delete user-created presets with the Delete Preset button, but the built-in ones that ship with Photoshop are there to stay.

Tip

![]()

If you want the Height and Width to use different measurement units, hold down the Shift key while selecting a unit of measure.

When you save a document preset, you can use the check boxes to choose which settings to remember. For example, if you turn off the Profile check box, when you later choose your preset from the Preset pop-up menu, Photoshop will not override the current working space.

Note that some built-in presets (those having to do with video) can also automatically add guides to the document. Unfortunately, there’s currently no way to save presets with guides yourself.

Clairvoyant Image Size. If you have something copied to the Clipboard when you create a new document, Photoshop automatically selects Clipboard from the Preset pop-up menu and plugs the pixel dimensions, resolution, and color model of that copied piece into the proper places of the dialog for you. If you’d rather use the values from the last new image you created, hold down Option (Mac) or Alt (Windows) while selecting File > New, or press Command-Option-N (Mac) or Ctrl-Alt-N (Windows).

Copying Sizes from Other Documents. In the New dialog, notice that all open documents are listed at the bottom of the Preset pop-up menu. If you want your new document to match an open document, simply choose the name of that document in this menu.

Keyboard Shortcut Tips

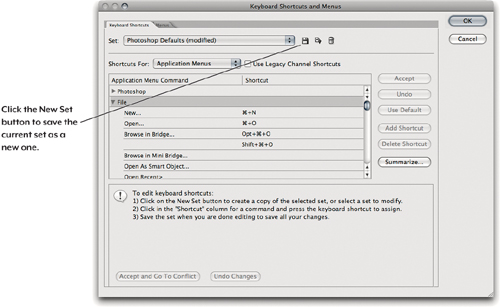

You can change keyboard shortcuts you don’t like, and you can add shortcuts and save them as part of a workspace that also includes your favorite panel arrangement and menu customizations. If you share the machine and don’t want to confuse others, you can save your keyboard shortcut sets.

Use Your Own Set. To edit or add a keyboard shortcut, choose Edit > Keyboard Shortcuts or press Command-Option-Shift-K (Mac) or Ctrl-Alt-Shift-K (Windows). If you edit the default set, it’s saved as “Photoshop Default (modified)” so that you can revert to the default (just choose Photoshop Defaults from the Set menu). Give your sets useful names; otherwise they can be lost when you choose another set or if you need to reset your preferences while troubleshooting a problem. To save a new set, click the New Set button (see Figure 6-16); by default, Photoshop saves the set in the proper location on your hard drive (inside your Photoshop application folder, in Presets > Keyboard Shortcuts).

Figure 6-16 The Keyboard Shortcuts and Menus dialog, showing the Keyboard Shortcuts tab

Tip

![]()

To export a list of all the features and their shortcuts, click the Summarize button in the Keyboard Shortcuts and Menus dialog. This file is saved in HTML format, so you can open it in any Web browser and print it from there if you want.

To customize keyboard shortcuts, follow these steps:

1. Pick Application Menus, Panel Menus, or Tools from the Shortcuts For pop-up menu.

Tip

![]()

If you don’t want to apply a new keyboard shortcut and the Shortcut field is still highlighted, press Cancel to back out of the change. Be careful. If you press Cancel a second time, you’ll close the dialog without saving changes.

2. Click an expansion triangle to reveal menu commands, and then select a command or tool from the list.

3. When the field in the Shortcut column is highlighted, you can type the keyboard shortcut you want to apply to this feature. If the shortcut is already in use, Photoshop alerts you and gives you choices.

4. To create another shortcut for the same feature (the flexibility is nice sometimes), click the Add Shortcut button. If you’re done with this feature and want to change another, click the Accept button. When you’re done applying shortcuts, click OK.

Resolve Conflicts with Mac OS X Shortcut Keys. When Apple introduced Mac OS X, they started using some keyboard shortcuts that conflicted with several long-established Photoshop shortcuts. For example, Command-H (Hide Selection) was taken for Hide Application by Mac OS X, Command-M (Curves dialog) was taken for Minimize Application, and Command-~ (tilde) was taken for cycling application windows. This tripped up Mac users and Photoshop veterans switching among Mac programs.

Tip

![]()

You can edit or add keyboard shortcuts for panel menus and tools, not just for regular menu commands. You can even save shortcuts for commands added by third-party features, such as filters, scripts, and plug-ins added to the File > Import and File > Automate submenus.

By default the Photoshop keyboard shortcuts always win, although you can also customize your shortcuts in Photoshop so that they don’t conflict with Mac OS X. If you don’t do that, you can still use the Hide Application and Minimize Window shortcuts by adding the Control key to the Mac OS X shortcut (press Command-Control-H for Hide Application, for example). (When you press Command-H for the first time in Photoshop CS5, you’ll be asked which shortcut you want to use so that you don’t have to configure it.)

For you old-timers upgrading from Photoshop CS3 or earlier, in Photoshop CS4 Adobe decided to take another swing at resolving these shortcut conflicts. Command-~ now cycles through windows, to be consistent with Mac OS X (on both platforms Ctrl-Tab still matches the Windows convention). This change caused channel viewing shortcuts to change on both platforms (more about this in Chapter 9, “Making Selections”).

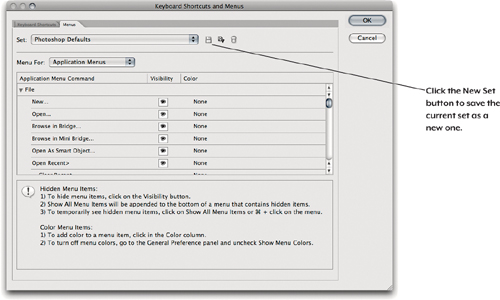

Menu Customization Tips

If you have trouble remembering which commands apply to your workflow, you can customize Photoshop menus by colorizing or hiding them. Menu customization works best when you spend most of your time using Photoshop in a very specialized way, or when you’re trying to train yourself or others in a specific workflow.

To edit menu commands, choose Edit > Menus or press Command-Option-Shift-M (Mac) or Ctrl-Alt-Shift-M (Windows). This is the same dialog used for customizing keyboard shortcuts, but when opened with the Menus command, it opens showing the Menus tab (see Figure 6-17). As with keyboard shortcuts, you can save your menus as a set. Note that you can’t hide the Quit or Close commands in Photoshop.

Figure 6-17 The Menus tab of the Keyboard Shortcuts and Menus dialog

Tips for Tools

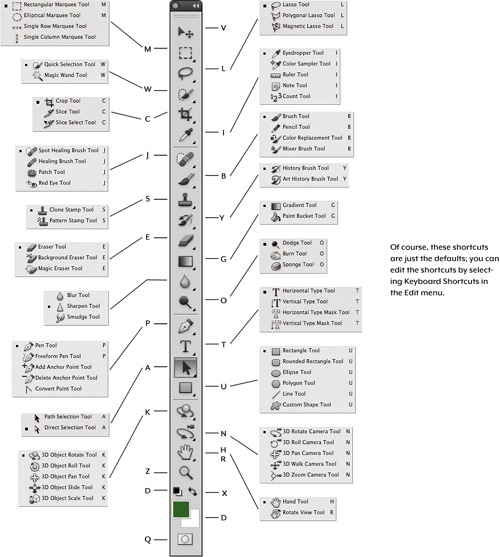

While it’s best to talk about a tool in the chapter where it applies the most (for example, the Selection tool gets a good long look in Chapter 9), it’s good to have an overview of tools in general, especially those that apply to more than one task.

Single-Key Tool Shortcuts. One of the most important productivity tips in Photoshop is how to select any tool by pressing just one key—no need to press Command or Ctrl. Figure 6-18 shows the tool shortcuts.

Figure 6-18 Tools panel tool groupings and single-key shortcuts

Some tools in the Tools panel keep multiple related tools undercover. For instance, the Dodge tool expands to reveal the Burn and Sponge tools. The slow way to access the different modes is to hold down the mouse button on the Tools panel icon to reveal the additional modes. A faster method is to press the tool’s keyboard shortcut once to select it, and then press it again with the Shift key to cycle through the choices. Press M once, and you jump to the Rectangular Marquee tool; then press Shift-M, and it switches to the Elliptical Marquee tool; press Shift-M once more, and it switches back to the Rectangular Marquee tool. (Note that this shortcut doesn’t cycle through the infrequently used Single Row marquee or Single Column marquee tools.)

Tip

![]()

A very efficient way to use Photoshop (or any Adobe Creative Suite software) is the two-handed method: Keep one hand on the mouse or stylus and the other hand over the keyboard, ready to press single-key tool shortcuts. By switching tools using your non-mouse hand on the keyboard, you can keep the mouse over the area you’re editing instead of repeatedly pulling the mouse or stylus over to the Tools panel.

Photoshop lets you change this behavior: If you turn off the Use Shift Key for Tool Switch check box in the General pane of the Preferences dialog, you don’t have to hold down the Shift key to rotate through the tools; each time you press M, you’ll get a different tool. I prefer to use Shift to cycle through tools, because it ensures that pressing a letter key selects the last tool you used in a tool group. If you cycle without Shift and the Tools panel is hidden (as in Full Screen mode), pressing a letter could cycle to another tool in the group that isn’t the tool you thought you were using.

Spring-Loaded Keys. Instead of switching tools all the time, you can switch to another tool temporarily by holding down a shortcut key instead of simply pressing and releasing it. For example, if you want to select an area and move it, without spring-loaded keys you have to press L to switch to the Lasso tool and then press V to move the pixels. In Photoshop CS4 and later, if you’re already using the Move tool, just hold down L and make the selection, and when you release L you’re back to the Move tool. The spring-loaded feature activates after you hold down a tool for a little more than one second.

Activate the Opposite Tool. Some tools have an opposite, kind of like an evil twin, except that the opposite tool isn’t evil (perhaps just misunderstood). When you’re using one of these tools, you can switch to its opposite by pressing Option (Mac) or Alt (Windows). For example, if you’re using the Blur tool, pressing Option/Alt temporarily changes it into the Sharpen tool. The same thing happens with the Dodge and Burn tools.

Change a Tool’s Blending Mode. You can change blending modes (Normal, Screen, Multiply, and so on) by pressing Shift- − (minus sign) and Shift-+ (plus sign). If a painting tool is selected (such as the Brush tool), this changes the mode of the selected tool. If the selected tool doesn’t use blending modes, the shortcut changes the mode of the current layer.

Belly Up to the Options Bar. To enter a value in the Options bar, there’s no need to move the mouse up there. Select a tool, press Return or Enter, and the first number field in the Options bar becomes selected and ready for you to enter a value. If the Options bar was hidden, press Return or Enter twice: once to display the Options bar, and again to activate a value.

Tip

![]()

As in any panel or dialog, in the Options bar you can move among fields by pressing Tab and Shift-Tab. Press Return or Enter to return to the image.

Brush Tips

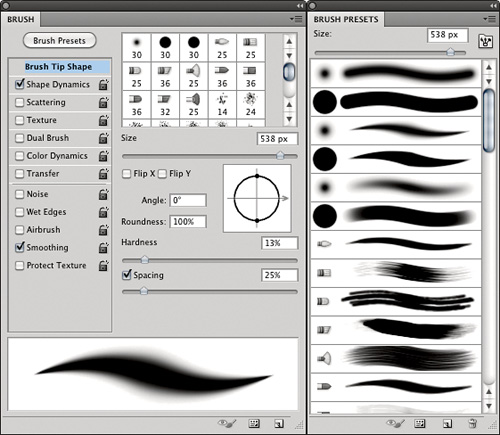

Use the Brush panel to customize Photoshop brushes and the Brush Presets to store saved brush settings (see Figure 6-19). Brush presets aren’t only for the Brush tool—they also work with any tool that paints, such as the Clone Stamp tool and the History Brush tool. The wide range of options is valuable for detailed retouching tasks.

Figure 6-19 The Brush panel on the left, and the Brush Presets panel on the right

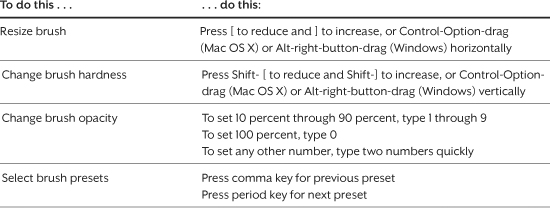

Brush Shortcuts. You’ll find brush shortcuts in Table 6-2. Note that the Resize Brush and Change Brush Hardness shortcuts include ways to edit brush size and hardness by dragging the brush with modifier keys pressed.

Opacity By the Numbers. Table 6-2 includes shortcuts for brush opacity, but note that if the Airbrush feature in the Options bar is turned on, typing numbers affects the Flow percentage rather than the Opacity setting.

Fast Brush Preset Selection. With a brush tool selected, right-click or Control-click (Mac OS X) the document to bring up a mini-Brush-panel right under the mouse, then double-click the size preset you want and the panel closes. Otherwise press Esc, Return, or Enter to close the panel.

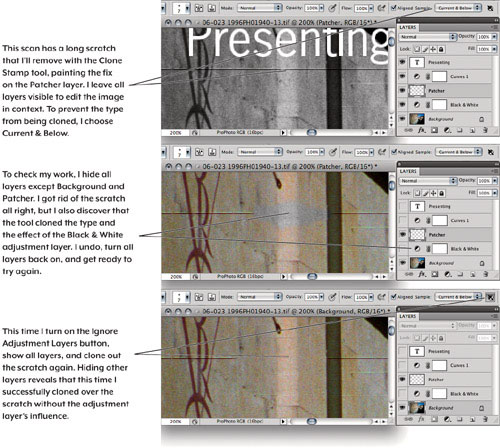

Sample Exactly the Right Layers. If you’re working on a multilayer image, tools like Smudge, Blur, Magic Wand, or Clone Stamp may frustrate you when you want to affect more source layers than just the one you’re working on. To solve this, use the Sample pop-up menu on the Options bar.

When Sample is set to Current Layer, the tool acts as though the other layers weren’t even there. If you choose All Layers, Photoshop samples from the other visible layers (both above and below it) and acts as though they were merged together. A third option, Current & Below, does what it says.

Tip

![]()

If you need to do a lot of cloning and retouching, the Clone Source panel is indispensable. I cover it in Chapter 11, “Essential Image Techniques.”

So what good are these options? One common use is when you want to patch or clone onto a new empty layer, leaving the original layers intact. If you’re unhappy with the results, you can simply erase the patches on the new layer and try again. Without the Sample menu options, you would be able to paint only on the layer you’re sampling. With the Sample pop-up menu, you can choose Current & Below or All Layers to paint on a blank layer while sampling from other layers that remain intact (see Figure 6-20).

Figure 6-20 Layer sampling options

The button next to the Sample pop-up menu is the Ignore Adjustment Layers button. Before Photoshop CS3, if you cloned or healed in a document that included adjustment layers and you sampled multiple layers, the sample would include the effect of the adjustment layers. This was frustrating, because the sample would not match the rest of the layer, and the adjustment layer would be applied again to the merged sample. It was necessary to remember to turn off adjustment layers before sampling multiple layers and then turn them back on—very frustrating. Ignore Adjustment Layers means that you can leave adjustment layers on and sample multiple layers perfectly. If you want your samples or selections to use only one layer as the source, select the layer and choose Current Layer from the Sample pop-up menu.

Cropping Tips

The nice thing about the Crop tool (as opposed to the Crop feature on the Image menu) is that you can make fine adjustments before committing. Just drag one of the corners or side handles. But you can do a lot more than that.

See What Gets Cropped. By default, Photoshop darkens the area outside the cropping rectangle so that you can see what’s going to get cropped out before you press Enter. To adjust this shading, click the color swatch in the Options bar (when the Crop tool is selected) and pick a different color from the Color Picker. Opacity controls how much of the cropped area is visible.

Rotate and Move While Cropping. You can crop and rotate at the same time with the Crop tool: After dragging out the cropping rectangle with the Crop tool, just place the cursor outside the cropping rectangle and drag to rotate the rectangle. When you press Return or Enter, Photoshop crops and rotates the image to straighten the rectangle. It can be tricky to get exactly the right angle by eye—watch the Info panel. Also, if the cropping rectangle isn’t in the right place, you can always move it—just position the cursor inside the cropping rectangle and drag.

Retain Cropped Areas. When you crop, you don’t have to lose what’s beyond the newly cropped edges of the document. After you drag a crop rectangle, click the Hide button on the Options bar; after you commit to the crop, the cropped-out pixels will be remembered as big data—material that hangs outside the actual visible image rectangle. Then, if you didn’t get the crop just right, you can either move the image around with the Move tool or recrop using a different rectangle (see “Expand the Canvas by Cropping,” later in this section). This works only on layers other than the Background layer; to use the Hide feature on the Background layer, double-click it to convert it to a transparency-capable layer.

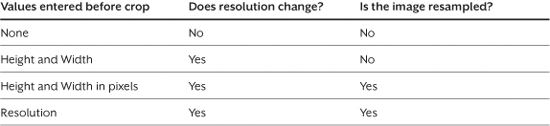

Cropping May Change Resolution and Resample. The Height, Width, and Resolution fields in the Options bar for the Crop tool save you the step of using the Image Size dialog after cropping, but beware! If you enter a Height and Width into the Options bar for the Crop tool, the resolution of your image will change, as shown in Table 6-3. And in some cases the image will also be resampled.

Table 6-3 How Crop tool options affect resolution and resampling.

Note

![]()

You can set the Height, Width, and Resolution values only before you start cropping. Once you draw a cropping rectangle, the Options bar changes to present different options.

What’s going on here? Simple math. Because resolution is the ratio of the image’s pixel dimensions to its physical dimensions (see Chapter 2), when you alter either variable the resolution must change. That’s why the only time resolution doesn’t change is when Height, Width, and Resolution are blank, so that dragging a crop rectangle applies no scaling and no resolution change—all it does is chop away a side or two of the image.

Tip

![]()

To empty the Width, Height, and Resolution fields in the Options bar, click the Clear button.

The reason resolution must change when you enter pixel dimensions is that Photoshop is forced to take the pixels that make up the crop area and resample them to the pixel dimensions you specifically asked for. There’s no mathematical way around that.

To completely eliminate the possibility of resampling when you crop, read on about cropping with the Rectangular Marquee tool instead of the Crop tool.

Tip

![]()

In previous versions of Photoshop, you might have used the Perspective check box in the Crop tool Options bar to correct keystone distortion, but in Photoshop CS5 the vastly upgraded Lens Correction filter is a far better way to fix this.

Crop to an Aspect Ratio. Let’s say you want to crop your image to a 4-by-6 aspect ratio (height to width, or vice versa), but you don’t want to resample the image (which adds or removes pixels, causing blurring) or change the image resolution. This is a common requirement in Web design, where pixel-perfect graphics would be ruined by resampling. The Crop tool can’t do this without resampling, so you’ll need a different technique. Select the Rectangular Marquee tool and choose Fixed Aspect Ratio from the Style pop-up menu in the Options bar. Then enter values in the Height and Width fields (here you’d type 4 and 6) in the Options bar. Select the area you want cropped, and then select Image > Crop.

Expand the Canvas by Cropping. Once you’ve created a cropping rectangle with the Crop tool, you can actually expand the crop past the boundaries of the image (assuming you zoom back until you see the gray area around the image in the document window). Then, after you press Enter, the canvas size actually expands to the edge of the cropping rectangle.

Tip

![]()

To toggle all snap-to options on or off, choose View > Snap. The shortcut is Command-Shift-; (Mac) or Ctrl-Shift-; (Windows).

Crop Near the Border. If you’re trying to shave just a sliver of pixels off one side of an image, you’ll find it incredibly annoying that Photoshop snaps the cropping rectangle to the edge of the image whenever you drag close to it. Fortunately, you can turn this behavior off temporarily by unchecking the command View > Snap > Document Bounds. Or you can hold down the Control key to disable snapping temporarily.

Eraser Tool Tips

The Eraser tool gets a bad rap because people assume you have to use a big, blocky eraser. No, you can erase using any brush—one that’s soft, or hard like an airbrush, or even textured. And you can control the opacity of the Eraser. Still, masking is usually better than erasing. The difference? Masks (covered in Chapter 8) can “erase” pixels without actually deleting them. They just hide the data, and you can always recover it later. Nevertheless, the Eraser tool can, on occasion, get you out of a jam. Here are a few tips:

Erase to History. The Erase to History feature (it’s a check box on the Options bar when you have the Eraser tool selected) lets you use the Eraser tool to replace pixels from an earlier state of the image (see “When Things Go Wrong,” later in this chapter, for more on the History feature). Erase to History more or less turns the Eraser into the History Brush tool. For instance, you can open a file, mess with it until it’s a mess, then revert parts of it to the original using the Eraser tool with Erase to History turned on.

Tip

![]()

When using the Eraser tool, you can temporarily switch to Erase to History by holding down the Option (Mac) or Alt (Windows) key.

Watch Preserve Transparency When Erasing. Note that the Eraser tool (or any other tool, for that matter) won’t change a layer’s transparency when you have the Preserve Transparency check box turned on in the Layers panel. That means it won’t erase pixels away to transparency; rather it just paints in the background color. Don’t forget that you can turn Preserve Transparency on and off by pressing / (forward slash).

Erase to Transparency. When you use a soft-edged brush to erase pixels from a layer (other than the Background layer), the pixels that are partially erased—that is, they’re still somewhat visible, but they have some transparency in them—cannot be brought back to full opacity. For example, if you set the Eraser to 50 percent opacity and erase pixels from a layer, there’s no way to get them back to 100 percent again. The reason: You’re not changing the pixel’s color, only the layer’s transparency mask. This isn’t really a tip; it’s just a warning. What you erase sometimes doesn’t really go away.

Gradient Tips

The Gradient tool (press G) is a quick way to create a transition between any two colors, or between color and transparency. A Gradient adjustment layer is an even more flexible way to use an entire layer as a gradient.

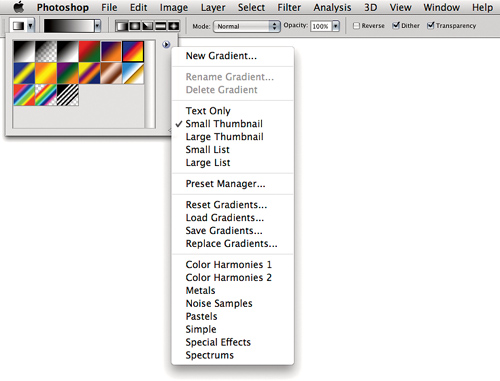

Gradient Presets. Some people work hard at creating a blend that fades away into transparency without realizing that it’s been done for them. The Options bar for the Gradient tool offers a pop-up menu with various gradient presets in it (see Figure 6-21). By default, these presets include gradients that use transparency. You can create or edit a gradient preset by clicking once on the gradient swatch in the Options bar. You can also select a different set of gradient presets from the pop-up menu to the right of the swatch.

Figure 6-21 Gradient presets and their pop-up menu

Maybe You Don’t Need to Use the Gradient Tool. If you’ve got a layer with nothing on it except a gradient, and you harbor even the slightest suspicion that you might need to edit that gradient later, consider creating it as a gradient layer. It’s a kind of adjustment layer that you can edit at any time. To create a gradient layer, choose Layer > New Fill Layer > Gradient or click the Create New Fill or Adjustment Layer button at the bottom of the Layers panel and choose Gradient Layer. You can edit its settings by double-clicking it in the Layers panel—much faster and easier than painting it all over again with the Gradient tool! However, if you’re creating a gradient on a mask, you’ll need to use the Gradient tool.

Avoid Banding in Gradients. On output, a blend in Photoshop can sometimes display banding—tonal or color breaks instead of a smooth transition. This is often a limitation of the specific type of output. A common remedy is to add noise to the blend, which Photoshop does using the Dither check box on the Options bar. Dither is on by default and in most cases should be left on. You can turn it off for uses such as scientific imaging or printing to a very high-quality output device that won’t cause banding.

If you still see banding even with Dither turned on, you could apply the Add Noise filter. But instead of applying noise to the entire gradient, try adding it in only a channel or two. View each channel separately (see Chapter 9) to see where the banding is more prevalent. Then add some noise just to the blend area in that channel.

Better CMYK Blends. If you’re going to make blends in images that will end up in CMYK mode, create them in CMYK mode. Sometimes changing modes from RGB to CMYK can give you significant color shifts in blends.

If you see problems with blue saturation in CMYK blends and you’re using a custom CMYK profile, try creating the blend in one of the CMYK working spaces that come with Photoshop and then assign your custom profile to the result. It sounds strange, but some custom CMYK profiles have a saturation “hole” that creates unexpected results in blues. For more about assigning profiles, see Chapter 4, “Color Settings.”

Notes Tips

You can leave notes in a Photoshop document to communicate anything that shouldn’t be output or printed with the image. For example, you can leave a note that includes processing guidance for the person on your team who’ll edit the image next, or include explanations for students or clients.

The Tools panel includes a Note tool grouped with the Eyedropper tool (see Figure 6-18). To create a new note, click the Note tool on the document; the Notes panel opens so you can enter text. Select a note to see its text in the Notes panel; if the Notes panel isn’t already open, double-click a note. If multiple notes exist in a document, you can use the arrow buttons in the Notes panel to see the previous and next notes.

To delete a note, select it and press the Delete key. To delete every note from a document, right-click or Control-click (Mac OS X) a note and choose Delete All Notes from the context menu.

Display Note Icons. You can drag note icons; I like to keep notes just visible in the corner of an image because in the past I’ve missed some that were outside the image area. To hide notes, press Command-H (Mac) or Ctrl-H (Windows), which toggles the View > Extras command. If you can’t see note icons in a Photoshop file but you suspect they’re there, make sure the Notes command is selected in the View > Show submenu.

Not Just for Photoshop. To send a Photoshop image with annotations to someone who doesn’t have Photoshop, relax. Choose File > Save As to save the image in Photoshop PDF format. In that format, notes can be read using Adobe Acrobat or the free Adobe Reader (in Mac OS X, you can also use Preview), and you can still edit the file using Photoshop.

You can load notes from a PDF document into a Photoshop document. To do this, in Photoshop choose the Note tool, right-click (or Control-click in Mac OS X) on the document, choose Import Notes from the context menu, select the PDF document, and click Load.

Tool Preset Tips

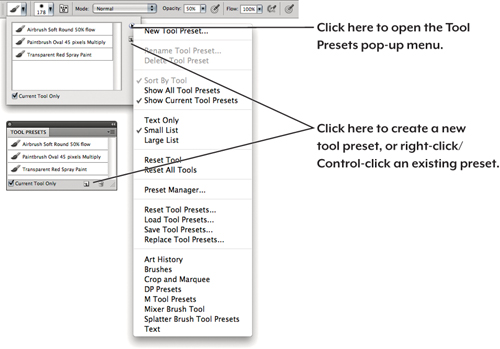

Each tool in the Tools panel offers options, such as the size of a brush’s diameter, or whether a selection is feathered, or what mode a tool will paint in (Multiply, Screen, and so on). It’s a hassle to remember to set all the tool options, especially if you need to change them frequently. Fortunately, the Tool Presets feature remembers multiple tool settings for you.

Tool presets live in two places: at the far left side of the Options bar and in the Tool Presets panel (see Figure 6-22). Choose Window > Tool Presets to open it. The panel is most useful for fine artists who switch among various tool presets, often within the same image. Production folks tend to keep the panel closed and select tools from the Tool Presets pop-up menu in the Options bar. One reason that tool presets live on the Options bar is that a tool preset includes the settings you’ve made in the Options bar.

Figure 6-22 Tool presets, their pop-up menu, and the Tool Presets panel

To create a new tool preset, select any tool in the Tools panel, change the Options bar to the way you want it, click the Tool Presets icon in the Options bar, then click the New Tool Preset button. Or even faster, Option-click (Mac) or Alt-click (Windows) the Tool Presets icon in the Options bar. When Photoshop asks you for a name, avoid confusion by giving the tool preset a descriptive name such as “Shape Tool Circle 50c20m.”

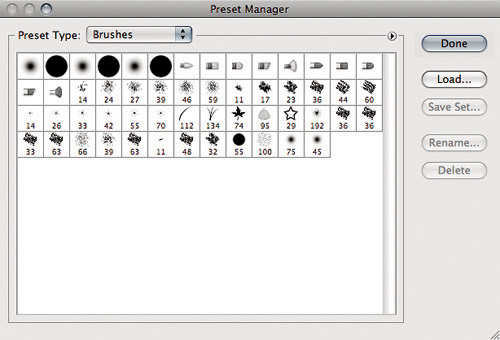

Photoshop comes with several premade collections of tool presets, such as Art History and Brushes. The trick to finding these (and to doing all sorts of other things with tool presets, like saving your own sets), is to open the Preset Manager dialog (see Figure 6-23) by choosing Preset Manager from the Tools panel menu; the same menu is available in the top-right corner of the Tool Presets pop-up menu from the Options bar.

Figure 6-23 The Preset Manager dialog with Brushes presets displayed

Unfortunately, there’s no way to edit a tool preset once you make it—you can only create a new one and delete the old one by choosing Delete Tool Preset from the Tool Preset menu. To reset tool options for either a single tool or for all the tools, Control-click (Mac) or right-click (Windows) on the Tool Presets icon on the Options bar.

Panels and Workspaces

Panels are both incredibly useful when you need them and incredibly annoying when they’re in your way, so it pays to get to know them. This section talks about panels and workspaces in general, and then discusses tips for individual Photoshop panels.

Panel Tips

Photoshop uses the same turbocharged workspaces that appear in the rest of the Adobe Creative Suite applications: You can group panels, dock them to the edge of the screen, or move panel groups to other monitors; collapse panels to save space; and collapse panel stacks to maximize screen space.

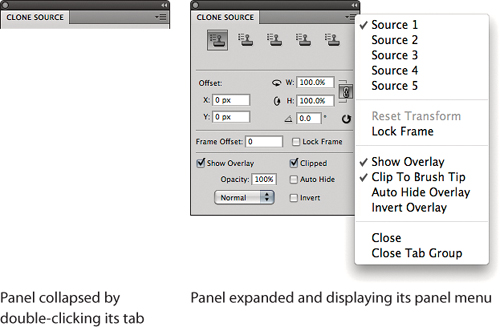

Save Space. Collapse or expand a panel by double-clicking the tab.

Panel Menus. Most panels have a pop-up menu at the top-right corner of the panel. To see it, click the icon that looks like a tiny menu (see Figure 6-24). Get to know the panel menus—sometimes it seems as though half of the power of Photoshop is inside the panel menus, which are easy to miss.

Scrubby Sliders. Earlier I mentioned scrubbing number fields in dialogs—Command-dragging (Mac) or Ctrl-dragging (Windows) over a number field (see “Dialog Tips” earlier in this chapter). This works in most panels too.

Rename Panel Items. To rename an item you created in a panel list, such as a layer name, double-click the panel item and type the new name. Text layers are special—they name themselves after the text you’ve typed and rename themselves if you edit the text. But if you manually rename a text layer, it will no longer update when you edit that layer’s text.

Tip

![]()

When entering a value in a panel, if you might change your mind, press Shift-Return in Mac OS X or Shift-Enter in Windows. This keeps the field selected so you can enter a different value.

Workspace Tips

Workspaces are extremely useful because there is no one right way to arrange things. When I connect my notebook computer to a color-calibrated desktop monitor, I like to use the higher-quality desktop monitor as the main image viewing area and place as many panels as possible on the laptop monitor. When I use the laptop by itself, there isn’t nearly enough room to replicate the two-monitor desktop arrangement so I become picky about which panels are visible. To switch instantly between the two panel arrangements, I saved each arrangement as its own workspace.

Tip

![]()

If there’s anything you want to change about how panels behave, check the Panels & Documents section of the Interface pane in the Preferences dialog. Your wish might already be granted.

Tip

![]()

A collapsed stack can be as narrow as a stack of unlabeled icons. If you’re still learning what the icons represent, widen a collapsed stack to reveal the labels; or to free up maximum screen space, collapse panels down to icons and use tool tips to see icon names.

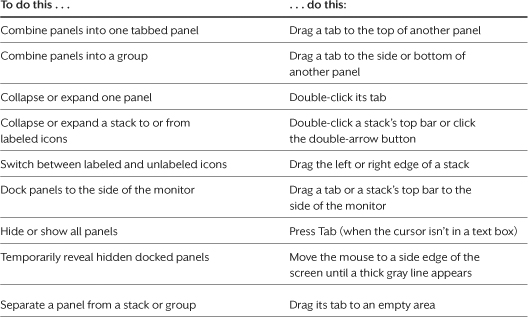

Ways to Combine. You can do so much more than just push panels around the screen. Table 6-4 describes how to get exactly the workspace you want; Figures 6-29 and 6-30 show you some of the many possibilities.

Table 6-4 Working with panels.

Figure 6-25 Workspace arrangements

Change Tab Order. It’s a minor thing, but when panels are in a tabbed group you can drag to change the tab order.

Workspaces are definitely personal. My friend David Blatner always keeps his Layers, Channels, and Paths panels together in one tabbed group. When he wants to work with one of these he clicks that panel’s tab heading or, better yet, uses a shortcut he defined for the panel. I always keep the Layers and Channels panels separate because I like to see multiple views of a document’s structure simultaneously. And I always keep the Info panel open because I’m always checking color values.

Figure 6-26 Display options for panels docked to one side of the monitor, and the workspace pop-up menu

Tip

![]()

The fastest way to get to a workspace with the mouse is to click the workspace pop-up menu at the right edge of the Application bar.

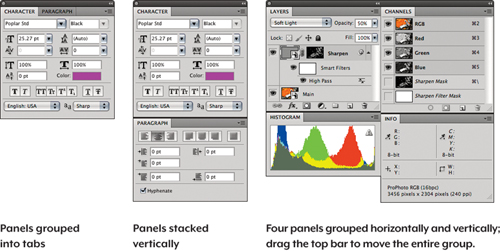

The Thin Blue Line. When dragging panels or document windows to combine them, always watch for the blue line at the edge of the destination panel or window (see Figure 6-27). It tells you when releasing the mouse will attach a panel to another one. If you see a blue rectangle, that means the panel you’re dragging will become a tab within the panel you’re dragging to. Figure 6-27 shows you what this looks like.

Figure 6-27 The blue line indicates that panels are about to group or dock.

Save Workspaces. To save a workspace, set up the panels the way you want them, optionally load any custom keyboard shortcut and menu sets, and choose Window > Workspace > Save Workspace. Saved workspaces appear on a workspace pop-up menu at the right edge of the Application bar as well as at the top of the Window > Workspace submenu. For even easier recall, use the Keyboard Shortcuts and Menus dialog to assign keyboard shortcuts to your favorite workspaces.

Workspaces and Monitors. You can dock only to the sides of your main monitor, not to the top or bottom. You can’t dock stacks at all on any other connected monitor. However, the ability to group panels both horizontally and vertically means you can create “flotillas” of grouped panels and drag the whole lot around on any connected monitor.

Tip

![]()

If you collapse panels to icons and don’t like expanded panels to stay open, open the Preferences dialog, click the Interface pane, and turn on Auto-Collapse Iconic Panels.

Self-Adapting and Resetting Workspaces. Workspaces adapt to you. For example, if you choose the Essentials workspace and move panels around, Photoshop updates the Essentials workspace with your adjustments. To revert to the workspace as it was last saved, choose Window > Workspace > Reset (workspace name).

Layers Panel Tips

It’s hard to conceive of a time when images were edited without multiple layers; many Photoshop users would never give up the flexibility that layers bring. Here’s an overview of the Layers panel (see Figure 6-28).

Display and Hide Layers. If you’re clicking the eye icons one layer at a time, there’s a faster way. Just click and drag through the column for all the layers you want to make visible. When you Option-click (Mac) or Alt-click (Windows) an eyeball in the Layers panel, Photoshop toggles the visibility of all the layers except the one you clicked on, which stays visible.

Create a New Layer. The fast way to create a new layer is to press Command-Shift-N (Mac) or Ctrl-Shift-N (Windows). If you want to bypass the New Layer dialog, press Command-Option-Shift-N (Mac) or Ctrl-Alt-Shift-N (Windows).

Duplicate Layers. Duplicating a layer is a part of my everyday workflow, so it’s a good thing there are various ways to do it.

• Drag the layer’s thumbnail on top of the New Layer button.

• Option-drag (Mac) or Alt-drag (Windows) the layer’s thumbnail to a new position in the Layers panel.

• Press Command-J (Mac) or Ctrl-J (Windows). If some pixels are selected, only those pixels will be duplicated to a new layer.

• Choose the Duplicate Layer command. This command is on the Layer menu, the Layers panel menu, and in the context menu when you right-click or Control-click (Mac OS X) a layer in the Layers panel.

• In the document window (not the Layers panel), Control-click (Mac) or right-click (Windows) a layer with a marquee, lasso, or Crop tool and choose Duplicate Layer from the context menu.

The method you use at any given time should be determined by where your hands are. (Keyboard? Mouse? Coffee mug?)

Select Layers. You can select layers using keyboard shortcuts. To select the next visible layer behind or in front of the current layer, press Option-[ or Option-] (Mac) or Alt-[ or Alt-] (Windows). To extend the selection to multiple layers, add the Shift key. To select the top or bottom layer, respectively, press Option-. (period) or Option-, (comma) in Mac OS X, or press Alt-. (period) or Alt-, (comma) in Windows.

Tip

![]()

You can delete multiple layers at once. Just select multiple layers in the Layers panel and then press the Delete key.

Automatic Layer Selection. Perhaps the fastest way to select a layer is to click it with the Move tool, but this doesn’t happen by default. To set this up, select the Move tool, turn on the Auto-Select check box in the Options bar, and then choose Layer from the Auto-Select pop-up menu. If it isn’t active when you want to select a different layer, activate the Move tool temporarily by pressing Command (Mac) or Ctrl (Windows) as you click.

A variation on Auto-Select is to click layer content while pressing modifier keys, skipping the context menu entirely. Using any tool, Command-Option-Control-click (Mac) or Ctrl-Alt-right-click (Windows).

On the other hand, Auto-Select can be irritating because it’s too easy to select the wrong layer. When that happens, right-click or Control-click (Mac) layer content and choose a layer name from the context menu that appears.

These techniques typically work only when you click on a pixel that has an opacity greater than 50 percent. (I say “typically” because it sometimes does work if the total visible opacity is less than 50 percent. See “Info Panel Tips,” later in this chapter.) In general, if you make sure you click on reasonably opaque areas of layers, these techniques should work fine.

Tip

![]()

If only one layer is visible when you press the layer arrangement shortcuts, Photoshop hides that layer and shows the next layer. This is great for cycling through a number of layers, though it doesn’t always work when you have layer groups.

Move and Duplicate Layer Masks. In the Layers panel, simply drag a layer mask’s thumbnail to a new layer. To duplicate a layer mask, Option-drag (Mac) or Alt-drag (Windows) a layer mask thumbnail.

Rearrange Layers. To move the selected layer down or up in the Layers panel with the keyboard, press Command-[ or Command-] (Mac) or Ctrl-[ or Ctrl-] (Windows). To move the selected layer to the bottom or top of the layer stack, add the Shift key to either shortcut.

Create Layer Groups. The more layers you have in your document, the more difficult it is to manage them. Fortunately, Photoshop offers layer groups in which you can work with adjacent layers as a unit. Layer groups work much like the folders on your desktop. Here are the basics:

• Layer groups act like a single layer. When you show, hide, move, or add a mask to the group, it affects all the layers in that group.

• To create a layer group, select the layers you want to group and then press Command-G (Mac) or Ctrl-G (Windows), which is the keyboard shortcut for Layer > Group Layers. You can also click the New Layer Group button in the Layers panel (see Figure 6-28), but then you have to drag layers into the group yourself.

• To add a layer to a group, just drag it on top of the group. Or to create a new layer inside the group automatically, select the group or any layer within the group (in the Layers panel) and click the New Layer button. You can remove a layer from a group simply by dragging it out.

• You can drag a layer group (with all of its layers) to another document.

• You can nest one layer group inside another, up to five levels deep.

Unfortunately, you can’t apply a layer effect to a layer group or use a layer group as a clipping mask (see Chapter 8).

Tip

![]()

To select groups more easily using the Move tool, choose Groups from the Auto-Select pop-up menu on the Move tool Options bar.

Layer Groups and Blending Modes. By default, a layer group’s blending mode is set to Pass Through, which means, “let each layer’s blending mode speak for itself.” In this mode, layers inside the group look the same as they would if they were outside the group. However, if you change the group’s blending mode, a curious thing happens: Photoshop first composites the layers in the group as though they were a single layer (following the blending modes you’ve specified for each layer), and then it composites that “single layer” with the rest of your image using the layer group’s blending mode. In this case, layers may appear very different depending on whether they’re inside or outside that group.

Similarly, when you change the opacity of the group, Photoshop first composites the layers in the group (using their individual opacity settings) and then applies this global opacity setting to the result.

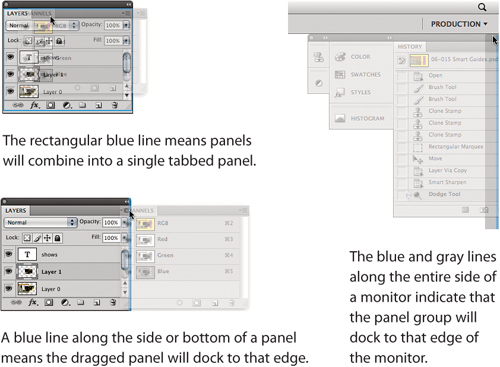

Layer Comps Panel Tips

If you like to keep your options open, you’ll love layer comps. The Layer Comps panel is like a clever combination of the Layers panel and the History panel: It lets you save the state of your document’s layers so you can return to it later. It might seem that the Layer Comps feature should be part of the Layers panel, but perhaps Adobe figured that the Layers panel was already complex enough. Although the snapshots feature of the History panel can perform most of the same tasks as the Layer Comps panel, the History panel is significantly more memory intensive and—this is important—layer comps can be saved with the document, while snapshots disappear when you close the file. Saving a layer comp makes almost no difference to your file size (each comp is only a few kilobytes on disk).

Tip

![]()

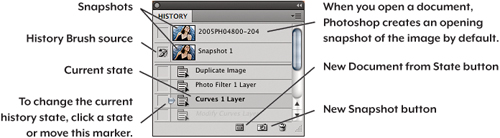

To open the Layer Comp Options dialog, double-click a thumbnail of a layer comp.