5

THE DEVELOPMENT PROCESS

Development Process Overview

The development phase is when the creative foundation for a project is solidified through visual and written materials. Inspired by an idea or a vision, writers and artists strive to capture the unknown. To some, it is a seemingly simple process; however, it can become much more involved than one might imagine. There are no hard and fast rules to development. The approach taken is dictated by the property, its source, and the individuals initially attached to it, such as the creator (referred to in this chapter as the seller) and the buyer. Putting together a strong development team to bring the concept to life is one of the most important steps in shaping a successful project. Although it can be challenging to match up key players who have a creative chemistry, when the right people are in place, the potential of a project is limitless.

The Role of the Producer During Development

Even if the producer is not the driving force behind a project from its inception (such as when a studio hires a producer to work on a project it already owns), it is important for him or her to be involved in the development phase as early as possible. How a project is shaped and launched is entirely dependent on its producer. Factors that directly influence this process are the story content and the project's intended budget and schedule. During the script writing process, one of the producer's primary duties is to ensure that the project is suitable for animation. Collaborating closely with a writer, the producer's goal is to flesh out as much of the story as possible so that the script can be considered “locked” prior to start of production. Partnered with the director and working with a select group of conceptual artists, the producer helps guide the creative efforts to establish an appropriate style and quality of animation. In addition to overseeing the writing and visual development process, it is important to keep the buyer satisfied. Just because a property is in development, there are no guarantees that it will get produced. It is the producer's job to keep the buyer completely confident that his or her investment is a sound business decision so that the funds can be put in place and production can be launched.

In exploring the possible paths to developing a project, the producer needs to assess its strengths and weaknesses. If the property is based on written material, the text may be used to create the visuals. On the other hand, it could be the reverse, whereby the visuals drive the script and a writer needs to be identified. It may be, however, that the project is based on a property that already has both elements in place, such as a comic book. In this case, the person attached to the property and/or its creator may act solely as a consultant or may be responsible for either the visual or written material, depending on his or her expertise. In all of the possible scenarios, the producer works with the creative executive, who is typically the representative of the buyer and the seller, to find and interview the appropriate candidates to help develop the project.

Independent studios and projects with lower budgets generally use freelance artists for visual development. When negotiating and hiring any member of the creative team, the producer needs to be clear as to whether they are “attaching” the talent to the project or simply bringing them on as a “work for hire.” If someone is integral to the project's success and is instrumental in selling it—such as an “A-list” writer or top director—the producer will probably attach him or her to the project, which ensures that the talent is available should the show go forward. The producer should be highly discerning, however, when attaching staff this early in the process. If the talent is not crucial to the project, they should be hired only for their specific services. If for example, the buyer is not impressed with a writer's output or an artist's work, yet that individual is attached to the property, this predicament could hinder the project getting picked up for production. Another item for the producer to consider before hiring anyone for the duration of the project is how easy or difficult it is to work with him or her. Starting with a freelance-type relationship is a great way of gaining insight into how someone works. Getting a project produced is challenging enough without having to deal with personality conflicts.

Projects developed in the larger animation studios are generally created by staff producers, directors, visual effects supervisors, and visual development artists. Writers may or may not be on staff. These studios typically have a number of artists who focus solely on conceptual artwork. As the lead storyteller, the director guides the artist(s) towards his or her vision. If no talent is initially attached to the project, the producer selects visual development artists, and possibly a director, to establish the look of the show. (See Chapter 4, “The Core Team,” for more information on this process.) In cases in which the director is already on board, he or she works with the producer to review portfolios and find the appropriate talent for the project.

In television, unlike features, the overall creative visionary on a project is usually the executive producer, who is often referred to as a showrunner. Note that if the property is the writer's concept, the writer typically plays the role of the executive producer. It is his or her responsibility to oversee the storytelling process and the show's visual development.

On both television and feature projects, the producer creates two important schedules. In cooperation with the writer, he or she generates a schedule based on the key milestones of the script as it evolves from premise to final draft. The writer receives creative notes from the producer, the director, the seller, and the creative executives at every stage of the scripting process. The purpose of this input is to make sure that the script is meeting the project's creative objectives from a narrative perspective as well as in terms of character development. On the visual front, the producer typically negotiates deals with the artists and creates a schedule for visual development. Working closely with the executive producer, the director, the seller, and the creative executive, the producer makes sure that the notes are addressed by the artists and that they are staying on track. If not, he or she reevaluates the scheduled plan and determines the timing of the next steps.

It falls on the producer's shoulders to pace development appropriately, allowing creativity to thrive and at the same time meeting long-term objectives. Although it is essential to adhere to schedules in production, applying strict deadlines to development can at times hinder the creative process. The producer has the balancing act of ensuring that the creative team has enough time and money to achieve their artistic goals and that the quality of artwork generated is suitable for production. As a result, the producer has to use his or her intuition to know when to push and when not to push. An artist's worst fear is working with a producer who has an assembly line approach towards artistic endeavors. Yet how can network or studio delivery deadlines be met if there is no schedule?

Besides keeping the creative team moving forward, another key responsibility for the producer is to keep the buyer and other significant players excited and enthusiastic about the future product. For example, one approach that can greatly help the buyer clearly envision a CG project, is taking the main characters and key locations into early surfacing and lighting tests. If the budget allows these additional steps, then the buyer can get fully behind the project and literally visualize why it is worth pursuing. It is important for all parties involved to understand that a concept in development can take many months—or even several years—before it is ready to be greenlit, as it is constantly changing and evolving into the best television show or feature production it can be.

As a project begins to take shape and the characters are more defined and developed, a producer must look at it in terms of applications in other mediums. Given today's transmedia marketplace, a property that has the legs to stand in multiple platforms—comprised of suitable content for games, mobiles and apps—has a stronger chance of succeeding, as it may start out in a smaller format and grow into a brand. In the case of a larger studio, a producer needs to begin to plant seeds and build support to help launch his or her project. Working with other divisions or ancillary entities within the company—such as the marketing department, consumer products, and online and music groups—it is important to engage them as possible stakeholders who may in turn provide additional funds or materials in support of the project. If a property has transmedia potential, buyers are more likely to support it through development and production, as they can see other possible ancillary revenue streams that can help offset their risks.

One important final item to note prior to getting into the development process is confidentiality of material. Starting at this stage of the production, it is critical for the producer to establish ground rules safeguarding the project from piracy. Confidentiality policies and procedures typically apply to script, all forms of artwork, and software development and must be adhered to throughout production and post-production. It is wise to watermark all script copies printed, to place burn-ins on all digital outputs created, and to keep a log of who is given what in order to closely track the possession and distribution of such materials.

The Curious Art of Developing a Known Property

Ellen Cockrill, Senior Vice President of Animation, Universal Studios Home Entertainment Family Productions

Although creating an animated show from scratch is an exciting adventure, taking a well-known property and translating it into film or television is an intriguing journey as well. The first challenge is to identify what is loved about the property in its original format. It's a critical step because it will inform all the creative choices going forward. This process involves exploring the key elements of the property—characters, art direction, and stories—and figuring out how to best translate their magic into the new medium. Such was the case with our work bringing to television Curious George, the beloved book property created by Margret and H. A. Rey.

Characters: The two main characters, George and the Man with the Yellow Hat, are delicately balanced in the books and we were mindful to retain that balance in the television show. Our supervising director and head writer both worked hard to ensure that George is always innocent in his actions so that he never comes off as a troublemaker or purposefully disobedient as he's following his curiosity and messing things up. This is what gives him his can-do spirit, keeping him sweet and full of charm. Likewise, we wanted to make the Man with the Yellow Hat an intelligent, lighthearted, and fully accepting “father” for George, even as he's witnessing George's chaos. Not only did we pursue this direction in the writing and directing, but we also searched for actors who could deliver just the right voice performances.

Because George doesn't speak an actual language, we needed to come up with alternative ways to keep him alive on screen. First, we made the book narrator an off-screen character, someone who could communicate George's point of view. However, we couldn't utilize as much narration as the books do, so we also incorporated “thought balloons” to visually portray some of George's thoughts. Finally, we had the writers not only script out all of George's actions and reactions but also his “chittered” dialogue. This gave our artists and our actor voicing George specific direction to work from. They then added their own terrific talents to bring George to life.

Art direction: To make an authentic translation of the book illustrations, our art director closely examined the color palette, shape vocabulary, line quality, use of shadow, and painting technique in the original work. He strictly adapted some of those design elements and strategically took liberties with others that might not play as well in the new medium. For instance, the book illustrations are done mainly with primary colors. In the animated show, we broadened the color palette but still attempted to create the sense that George's world is one of bright, primary hues. We also endeavored to use the art direction in a way that retained the books' timeless feel. This approach, hopefully, helped make the series “evergreen.”

There was one design aspect of our show that required deep deliberation before proceeding into animation, and that was the interpretation of George's eye shape. In the books, George has simple “button” eyes, but when attempting to translate that look into animation, we realized that he was able to convey more expression and emotion when given a more detailed eye design with white surrounding his pupils. This change was weighed heavily, but when considered in combination with the fact that George does not speak in human language, eye design proved too valuable an animation tool to oversimplify.

Stories: Another essential aspect of development we considered was where the stories could logically go from where they left off in the books. We knew our curious little monkey character would lend himself to countless entertaining scenarios; it was one of the reasons Curious George was initially viewed as an outstanding property for adaptation. We realized his curiosity would also be a great means for introducing preschool audiences to basic math, science, and engineering principles. To develop our stories, we worked with preschool education specialists to come up with concepts that would be educational as well as entertaining. The specialists then continued to give helpful comments throughout production to make the episodes as enjoyable yet informative as possible.

In the versatile world of animation, imagination and creative analysis easily combine to create memorable experiences for fans of endearing characters, old and new. You just have to be curious enough about the development adventure to make the most of it!

Figure 5–1 Curious George (CG: ® & © 2010 Universal Studios and/or HMH. All Rights Reserved).

The Writing Process

The key to a successful project is a great script. You can have some of the most beautiful and complex animation in the world, but if the story doesn't work and the characters are not compelling, chances are that the show won't be either. In animation, there are several ways to approach scripting, depending on the genre, format, and length of the project. In the old days, most of the famous cartoon shorts were created directly from an outline to storyboard. Gags would be conceived in a room of artists bouncing ideas off each other. These ideas would then be pitched or acted out by the directors and/or animators. This approach enabled everyone to be spontaneous and come up with some classic comedy, and it is still a popular technique used for short-form projects. In terms of longer formats, once a script is available, it is common to hold brainstorming sessions with the story artists to come up with gags and/or solve story problems. Whatever the method used, the goal of the producer is to get the best writer, story boarding team and script possible.

Writer's Deals

You are finally ready to hire a professional writer to take the story idea to the next stage. How do you set that up? In the larger studio system, the business affairs department, with input from the creative executive and producer, negotiates the writer's contract. Rates paid depend on the type of project, budget, and the background experience and perceived value of the writer.

For a series, writers' fees can vary greatly for a traditional half-hour “Saturday morning” script versus a prime-time show. Feature scripts also range greatly in cost depending on the stature of the writer, his or her “quote” (the amount they received on their last project), and the number of writers brought in to work on the script throughout the development phase. It is standard that a writer is not expected to make less than his or her quote, and—depending on the nature of the project—the writer generally expects an increase in pay. It is also important to respect practices established by the Writer's Guild of America if the writer is a member of this group. If a studio is a member of the animation union, in-house writers are covered by that union. In such cases, writers can expect minimum scale rates. However, because these fees are considered low, scale would be an appropriate payment mostly for a first-time writer.

Each studio has its own standards and processes in place for payment if the writer is non-union. If the writer is union, payments must be paid per union rules. Commonly, the payment installments are made based on the breakdown of the script phases. In most cases, certain payments will be guaranteed to the writer and others will be considered optional, based on performance. Payments are made as the writer reaches key milestones. An initial fee is usually paid upon commencement of writing. The balance is paid once the outline is completed, and the rest is delivered, for example, when the draft is handed in for review and notes. A typical breakdown follows:

- Premise (for television)

- Story beats/outline (with two revisions)

- Treatment (with two revisions—for long formats)

- Script: script fees can be divided (first draft, final draft, polish)

In most companies, no payments are made until a Certificate of Authorship (C of A) has been signed. The C of A assigns the material rights to the buyer for the writer's services on the script, which means that all written material and ideas are the property of the buyer.

Series Bible

A bible is the written concept that sets up the key elements for a series. It includes a description of the show as a whole, and it defines the main characters, their relationships with one another, the tone of the show, and the target audience. Premises (explained shortly) are also written for potential stories and episodes. Once the visuals are designed, they are placed in the bible to help enhance the storytelling. After the bible is assembled and signed off by the buyer, the seller, the executives, and the producer, it has multiple functions. Primarily, it is used as a tool for the writing team to help ensure consistency throughout the writing process. The series bible is also utilized by the casting director to select voice talent. Finally, it is used by the artistic crew to help them better understand the tone of the show and how the characters and plot are intertwined.

Script Stages

The writing of a project progresses through a number of stages before it is ready for production. In the case of a traditional narrative structure, this process includes establishing and setting up the characters, their world, their conflict(s), and the resolution. The following sections offer explanations of each of these stages.

Premise (Television/Short Form)

The premise is a paragraph or two that outlines the main story concept. Included are the main characters, the basic conflict, any complications, and how they are resolved.

Outline (Long-Form and Short-Form)

For long-form productions such as direct-to-DVD, features or television specials, an outline describing the key plot points of the story is an important foundation for script writing. This outline is broken down into three acts and chronologically lists each significant emotional and action moment portrayed in each sequence within each act. If storyboard artists are working on the project, it is often helpful to have them create visual representations of each plot point on this outline, generating a story beat board that can further inspire the writing and artistic teams. This artwork enables the crew to keep on track with the creative goals sequence by sequence.

In television, the outline is a more detailed version of the premise. It is generally a sequence-by-sequence breakdown of the story with a few lines of dialogue added to flesh out the characters, giving a project with multiple writers a sampling of the tone. In the outline, the flow of the action is spelled out. It is easier to change the structure of the story at this point rather than re-working it in the script stage. The number of pages may range from two to ten, depending on the format being produced.

Treatment (Long-Form)

The treatment is an expansion of the outline. It is generally a 20–25 page document that is broken down into a three-act structure and includes some dialogue.

Pilot Script

The pilot script is used in television and in some ways is similar to the series bible. Its purpose is to give the reader a sense of the tone of the show and to set up the characters while explaining their relationships to one another. If this script is successful, it may be produced as a story reel, or be fully animated prior to a series being greenlit. Like all television scripts, it would follow some or all of the various steps outlined next.

First Draft Script

A script is written in several drafts or phases. The first draft fleshes out the story arcs, adding dialogue and action. In the case of a television series, a story editor may ensure that the script is ready for production. He or she also makes certain that the writing across all episodes is consistent in following the characterizations and tone of the series as established in the bible. Once complete, the first draft is given to the key creative staff on the project—usually the producer, director, and creative executive—for notes. A half-hour script is between 25 and 35 pages long. A feature script for an 80-minute film can be anywhere from 80 to 110 pages, depending on whether it is dialogue-heavy or action-driven.

Second, Third, and Even Fourth Drafts or More

Each draft incorporates new notes given to the writer with the goal of improving the story through the revisions. The process of writing continues until the script is considered ready to go into production. On a series, the story editor may be responsible for inputting the notes after the second draft. In long form, it is very common for the script to go into production in segments while the rest of it is still in development.

In feature development, it is also common for new writers to be hired if the buyer/creator is not getting what he or she needs from the originally hired writer—it is always better to find the right tone in the script earlier rather than later. New writers may also be brought in to handle specific script tasks, such as punching-up the comedic content or deepening the emotional pull of the story.

Polish

This is the stage at which final touches are completed on the script. Rarely is the structure of the script altered at this point. The focus is most often on improving dialogue or clarifying content. It is not uncommon on feature films to attach a new writer to the project for the final dialogue pass.

The Feature Film Script

In general, the feature script is never locked by the time preproduction begins, the reason being that the story is further developed by the collaboration of the director, the storyboard artists, and the scriptwriter. The storyboard artist or, at times, a previs artist, takes a written sequence and visualizes the action. The goal here is to further improve the script. If the budget allows, the scripting process may be concurrent with the storyboarding pass. (See Chapter 8, “Pre-production,” for more information on this process.) Using the treatment or outline as a starting place, the writer holds a series of meetings with the project's director, head of story, and several of the storyboard artists to work out the story and flesh out the characters. Tracking these key character and story arcs as well as plotting out what is accomplished in each scene enables this group to further refine the story.

After these meetings, the writer creates a draft of the screenplay. The storyboard artists illustrate sequences based on the written material. Upon completion of this assignment, the group meets again to review the board, the animatic, or pre-vis sequence and to come up with more ideas and ways to improve the story. The artist pitches the board to the producer, director, and writer. Based on the producer's and director's decision, the artwork and script are revised as necessary. This process continues until everyone is satisfied and considers the sequence ready for production. This approach is very interactive and is a productive method of improving the script. Given that animation is a visual medium, it helps ensure that the words in the script make the transition to the screen effectively. (For more information, see Chapter 8, “Pre-production.”)

Production Scripts

Once production begins, the greenlit script goes through a number of stages. It needs to be constantly updated throughout the production process as lines and scenes are revised, added, and deleted. This information must be carefully handled through the production's centralized tracking system so that everyone affected by the changes is informed and that nothing is missed during production. Another key reason to track all versions of a script is for the purpose of determining screen credits. If the project falls under the jurisdiction of a union, this tracking is required, especially when significant changes are made. The following sections define the different types of scripts created during production.

Numbered Script

In the numbered script, each line of dialogue in the production script is numbered. This script is used during the voice recording session as a reference tool. These numbers are used and referred to by the actors, directors, recording engineers, and editors. All the description and scene information is left in the script.

Recording Script or Engineer's Script

In the recording script, typically all descriptions and scene directions are deleted, leaving only the lines of dialogue. This script is used to keep track of the recorded dialogue and the various takes the actor records. The director's select takes are circled on the script and are given to the editor to cut into the track. These lines are referred to as circle takes.

Conformed Script

Once the animatic is locked for production, the script is updated and conformed to match it. (see Chapter 8, “Preproduction.”) All changes or deletions are included in the conformed script. Conforming the script can be an ongoing process as opposed to a one-time step.

Automatic Dialogue Replacement (ADR) Script

The ADR script shows the additional and replacement dialogue only. Used during post-production, the ADR script contains the lines of dialogue with their corresponding line number. These lines are also numbered with reference to time code. (For more information on ADR, see Chapter 10, “Post-production.”)

Final As-Aired/Released Script

Because many changes can take place in post-production, the final-as-aired script is conformed to match the actual as-aired or released version. It is very important that this script be created because it is needed for closed captioning and foreign-language dubbing.

Script Clearances

It is key to begin the script clearance process—that is, ensuring that legal permission is obtained for details of the script—as early as the project begins to solidify. Under the guidance of an attorney or legal affairs department, the earliest details to clear should be the names of main characters and locations. In the event that a name does not clear, meaning that it is already legally claimed in a similar capacity, it is best to replace that element earlier rather than later. In such instances, the legal representative may be able to provide comparable names that are cleared for use to facilitate the replacement of the unavailable name. This process continues as new character and location names are suggested. The final script as a whole also requires clearance.

Visual Development

The two main visual elements necessary to set up the world of an animated project are characters and locations. Depending on the production, there may be many line and color drawings, just a few conceptual paintings, rough CG models (if applicable), or any combination thereof that helps to clearly bring the project to life. Similarly, dozens of artists may be developing a show, or there could be as few as one or two individuals wearing multiple hats, such as a production designer, art director, and/or character designer.

It is during the conceptual stage that the style of a show is established. Is it going to be cartoony, realistic, highly stylized, or a combination thereof? If there is absolutely no visual starting point on a property, one approach may be to assign several visual development artists to design the key characters and locations in a variety of styles. The director and producer can then review the artwork and use it as a jumping-off point for creating the look of the show. Conceptual art usually begins as a fairly loose approach to the characters and their environment. As development progresses, the style becomes more distinct and the artwork is further refined to match the direction that the project is taking.

When the show gets close to the pre-production phase, the producer's most consequential task is to have finalized and approved artwork. The final signoff on the character designs, location, and props is a requirement for the smooth transition of a project from development onto production.

This early stage in visual development is an opportune time for the buyer and other members of the team to make changes and give their input. At this point in the process, it is not that expensive to explore new ideas or even restart if the current designs are not working. Given the enormous cost of revisions once a project is in production, it is crucial to nail down and agree to as many key decisions as possible during the development stage. When revisions are made, a domino effect occurs because so many different elements need to be altered in order to keep the show consistent. (See Chapter 9, “Production,” for more information on this process.) As a result, the cost implications to the schedule and budget can be significant. On lower-budget television projects, there may not be enough money to make changes, so it is necessary to finalize all key creative decisions prior to the start of production. Once the character, location, and prop designs are considered final and approved and handed off to animation, they are considered to be locked items—that is, no longer open to major revisions, especially if they are being sent to a subcontractor. (See Chapter 8, “Pre-production,” for more information on the model package.)

It is also wise to consult legal advice during the visual development process for all main characters, props, and logos created. Similar likenesses to real persons or products may involve some risk of future litigation, and the acceptance of this risk should be discussed and determined between the owner of the project's copyright and the legal and business affairs group. An exception to seeking clearances takes place when they are used in parody, such as in the Academy Award00AE-winning short “Logorama” (Figure 5-2).

Figure 5-2 Logorama (LOGORAMA by H5 [François Alaux, Hervé de Crécy, Ludovic Houplain] © 2009—Autour de Minuit Productions).

CASE STUDY: Luna

In order to best explain the various stages of animation from development to pre-production to production, the progression of Luna—an original short-form film that was created, developed, and produced by Rainmaker Entertainment—will serve as a case study. Luna is a CG project produced for final delivery in both 3D and 3D stereoscopic. This case study illustrates how a story can be produced for animation by outlining the various stages of its progress from its earliest conception to final output. See the Preproduction and Production chapters for process specific examples.

All of the elements from Luna illustrated in this book can be viewed interactively at www.rainmaker.com/luna. The website presents 2D imagery with color as well as moving turntables, animation tests, and the various stages of the story reel from boards through final animation, lighting, and sound. The ![]() symbol will serve as a cue that the element being discussed can also be viewed online.

symbol will serve as a cue that the element being discussed can also be viewed online.

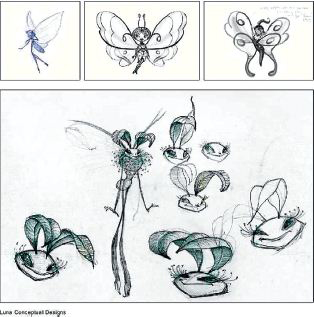

The initial project was inspired by the image in Figure 5-3. The idea that a caterpillar was in love with a moth, yet living in a lamp with no way to pursue the object of his affection, was intriguing to the Rainmaker executives. From this singular image and simple concept, they developed a story about the power of attraction and unrequited love. After an extensive story development process, the final synopsis of the film landed as follows, presented here with a sampling of the visual development artwork that was created in order to establish the look of the characters and environment for Luna (Figures 5-4through 5–7). The team found Silky as a caterpillar before determining his look as a moth:

Happily lazing about in his home, eating leaves and enjoying the view, we meet Silky the caterpillar.

It is dark. A light suddenly illuminates Silky's home. A shadow ominously casts upon him. Startled and afraid, Silky tries to hide but has nowhere to go. He nervously peeks up and is surprised to see a most beautiful creature—Luna the moth, who smiles and flutters about gracefully. It appears she is flirting with him. Silky is immediately smitten. It's love at first sight, and Silky's alter ego—a Spanish matador—transforms him. Using his many charms and talents, Silky makes his move to woo and romance Luna&

Luna too appears smitten, but the two “lovebugs” are separated. She bangs on the glass wall desperately trying to reach him. Her efforts are futile. As Silky continues with his debonair moves, the music builds and the two of them become more and more attracted to each other. The music crescendos, their lips pucker for a kiss, they rush towards each other. Thwump! Silky hits the glass. Thwump! Luna hits the glass. Silky's puckered lips have nowhere to go. And then the light goes out. Luna is dramatically upset. Silky doesn't understand what is happening.

Figure 5-3 Luna: Concept development.

Cut outside to reveal that Luna is simply a moth attracted to the bright light in a street lamp.

Returning to Silky's POV, he realizes the light was the focus of her attraction. Heartbroken, Luna flies away. As she leaves, Silky is devastated, his heart also broken. Despondent, he attempts to return to his old life of leaf eating—but without love, there is no longer joy. He cocoons.

Time passes. Silky breaks free from his cocoon. He sees his reflection in the glass and marvels at his new body. Unraveling his wings, he is thrilled to discover that he has metamorphosed into a moth. A shadow of a moth flies by, reminding him of Luna. Another metamorphosis takes place: Silky as the “Don Juan of Moths” emerges. Determined to find the love of his life, Silky breaks free from his old home in search of Luna.

Figure 5-4 Luna: Character development for Luna.

Figure 5-5 Luna: Character development for Silky as a caterpillar.

Figure 5-6 Luna: Character development for Silky as a moth.

Flying up through the clouds, he spots her. She sees him too. They come together. It is again love at first sight, but this time it is mutual. They do a dance. Backlit by the moon, the setting is romantic. It is time for the kiss they could never have: they pucker, close their eyes, and lean in towards each other. As their lips are about to touch, a light turns on. They look up and choose to ignore it. But alas, another light and then another turns on. They continue their pucker; Silky and Luna look at each other, but the power of the light shines even brighter and begins to sparkle. Finally, the pull of attraction is too strong.

Following Silky, the camera pulls back to reveal Luna racing towards one street lamp, and Silky towards another. Pulling back even further, more street lamps are revealed, with many more moths equally enthralled, attracted, and in love … with the light.

Figure 5-7 Luna: Location development.

Conclusion

Using the script, bible (if applicable), and conceptual artwork, the producer analyzes the complexity and cost needs of the project to create the production plan, with input from key executives (production and creative). The development materials (the script and the artwork) produced along with this plan are used to get a greenlight for production. After the project has been greenlit and all of the items listed earlier are completed and signed off on by the key players, the script is ready to go into the next phase of the process: pre-production, which is discussed in Chapter 8.