3

HOW TO IDENTIFY AND SELL PROJECTS

This is where the adventure begins: identifying a concept. Imagine yourself as a U.S. Navy SEAL. You are on a reconnaissance mission. You need extensive preparation and training for the process. Every step that you take can potentially have larger repercussions, so you must be mindful of every action. Equally as important, you must pace yourself through all kinds of obstacles in a labyrinth. Before embarking on this mission, you need to have a thorough understanding of the landscape and mindscape ahead, which involve these key stages:

- Spotting the idea

- Defining the format and target audience

- Identifying the buyer

- Developing pitch material

- Hiring representation

- Entering negotiations

The selling journey of every project is unique depending on who you are, what you are pitching, and to whom you are pitching it. There is no one distinct path to follow, nor is there a specified timeframe in which you should expect results. This fluidity may seem frustrating to navigate at times, but it provides you with the ability to tailor your pitch to best suit your individual situation and project. One thing is consistent, however: at each step along this journey you need to be open to feedback and possible changes that will inevitably arise—and you need to be ready to respond quickly and intelligently.

Spotting the Idea

Your first goal is to find an idea. You might get inspiration through a piece of art, a dream, or a book. There are no set rules as to when or where you can find a winning concept, but the key is having the ability to recognize one and know how to identify, package, and ultimately sell it to the appropriate buyer.

As a producer, you may have an original idea or explore one that has been previously established. Going down the original idea path requires a strong conviction that the concept and characters are highly appealing and viable in the marketplace. If you choose to develop and sell something that is already established, you can search for materials in a wide variety of locations: potential story ideas can be found in comic books, graphic novels, classic tales in the public domain, toys, and children's books and songs, for example. Be sure to keep in mind that unless you are the creator or the material is considered to be in the public domain (that is, anyone can use the rights as no one person or entity owns them), the next step must be exploring how you can obtain the rights to use it.

Searching for brand-new material? Countless “desktopcreated” original shorts are available for viewing through publicly accessible videos on websites such as youtube.com, vimeo.com, or funnyordie.com. Animation podcasts and artists' personal blogs are a direct peek into such creative outlets. More often than not, the artist has created the postings with the hopes of having his or her material picked up for development as a feature film, television series, web, game, or mobile content, unless otherwise noted. It's an easy way for any artist to get his or her work out into the world and an equally easy way for producers to find the next great idea or artistic talent without spending a dime or leaving the comfort of their home or office.

Comic books, comic strips, and graphic novels are among the easiest types of material to adapt for animation. With an established visual style, fully developed characters, and a storyline, the producer has almost all the main ingredients necessary to start pre-production. Notable comics and graphic novels that have been sold to studios include Over the Hedge (see Figure 3-1), from the comic strip written and drawn by Michael Fry and T. Lewis, and Persepolis, the Academy Award-nominated film based on Marjane Satrapi's graphic novel. Typically, the best places to locate comic books and graphic novels are comic book conventions. For example, the annual Comic-Con International summer event in San Diego is the largest comic book convention in the world; all the major publishers, distributors, and many independent creators come to show and sell their books. Because not everyone can travel to conventions, visiting and perusing a neighborhood comic book store is another good way to familiarize yourself with the world of comics. The Internet also hosts a myriad of web comics and podcasts related to comics.

Figure 3-1 Over the Hedge (“Over the Hedge” ® & © 2006 DreamWorks Animation LLC, used with permission of DreamWorks Animation LLC).

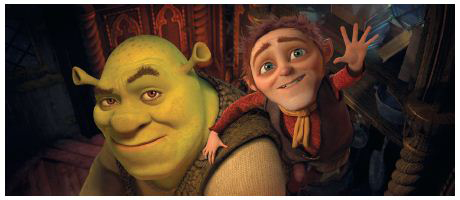

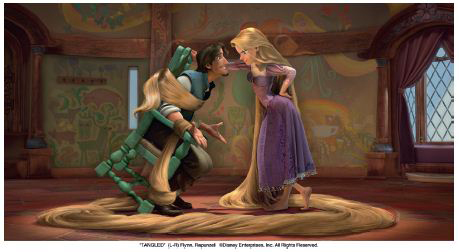

Children's books are another bountiful source for animated projects. Successful examples of these adaptations include Curious George, Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs (Figure 3-2), and Shrek (Figure 3-3), to name just a few. Even contemporary tween- and teen-targeted literature has had great success when developed into animated films, such as How to Train Your Dragon and Coraline (Figure 3-4). Children's classic literature is an obvious choice for development, with its reliable marketability and name recognition. It is rare, however, to find a well-known children's title that has not been already optioned or remains in public domain. Something to keep in mind is that popular books can be costly to option, so depending on your access to financial resources, this may or may not be a feasible route. It is therefore useful to look for stories that are either newly published or are already in the public domain. Looking for material that is hot off the press? Consider attending books fairs or visiting your local independent bookstore and asking the person in charge of ordering new titles to share his or her favorite recent picks. Examples of public domain stories are Tangled (Figure 3-5), based on the fairy tale of Rapunzel, and Hoodwinked (Figure 3-6), a twist on the folktale of Little Red Riding Hood. Taking a famous story and adding a new spin to it is very popular, as is evident in the box office success of these titles.

Figure 3-2 Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs (© 2009 Sony Pictures Animation, Inc. All Rights Reserved).

Figure 3-3 Shrek Forever After (“Shrek Forever After” ™ & © 2010 DreamWorks Animation LLC, used with permission of DreamWorks Animation LLC).

If you are interested in developing original source material but can't write or draw, you may want to team up with an established artist or up-and-coming talent in the field. If your funds are limited, you might consider teaming up with an artist who is willing to accept a smaller fee in lieu of partial ownership of your project. In search of talent? Animation festivals are excellent forums for finding great material and meeting animation directors and animators. At such events, you are able to view the work of renowned artists as well as student films that might be perfect for developing into commercial projects, such as the case of A Grand Day Out (Figure 3-7), the first of the “Wallace and Gromit” stories by Nick Park, which was discovered while it was still in production as Park's graduation project for the National Film and Television School in the United Kingdom. At first glance, developing and preparing original material to sell may seem like a relatively easy path to follow. It is deceiving, however, as coming up with a strong story that feels fresh and has a unique voice and compelling characters takes creativity and time. A key concept to keep in mind is that an original idea is a risky proposition for buyers, as it is untested. Although it is impossible to assess the future success of a project, the basic idea must nevertheless be distinctive and promising enough in order for the buyer to be willing to take a chance on it and invest the resources to get it into development and production.

Figure 3-4 Coraline (© 2009, Courtesy Focus Features).

Figure 3-5 Tangled ((L–R) Flynn, Rapunzel © 2010 Disney/Pixar. © Disney Enterprises, Inc. All Rights Reserved).

Before spending money on a property, it is wise to do some research to make sure that there is actually a market for your concept. You may think you have found the most exciting superhero since Batman, but there may be similar properties in development, or it could be that superheroes are not currently popular. Market research is therefore essential. One studio may only look for original characters; another, preestablished properties; yet another may seek dramatic prime-time material. Although it is not easy, you should consider picking up the phone to cold-call executives and find out what they are looking for. Do your homework in advance by familiarizing yourself with the type of shows that each studio has produced. If indeed you do get the opportunity to speak with someone and your idea seems to fit the bill, be prepared to summarize and pitch your idea in just a few sentences, as discussed later in this chapter.

Figure 3–6 Hoodwinked (© Kanbar Entertainment, LLC).

Figure 3–7 A Grand Day Out (© NFTS 1989).

Perseverance and Belief in Your Vision

Jill Sanford, Director, Original Series, Disney Television Animation

In development, we are always looking for projects that have that special something—that little spark of potential, whether it's in the characters or the concept or the artwork or the talent pitching the project. In terms of finding that gem of a property, there are no rules for how a project comes into us in a pitch form. Sometimes it's a great one-line pitch or a funny drawing of a character, and sometimes it's a 50-page bible. Each story and character has its own strengths and merits, depending on where it is in the development process. The question that many people ask is: what is it that makes a project stand out and how do you know if it is going to be a hit? The truth is that no one knows what is going to hit big, but we try to stack the deck as much as we can to give each show we get behind the best shot possible. Because we see so many ideas, picking those special projects and people that we want to invest the time and resources in is based on an understanding of our brand, combined with experience, intuition, and sometimes a little bit of luck. A great example of this is the story behind Phineas and Ferb and how it developed at Disney Television Animation.

When the idea for Phineas and Ferb initially came to our offices at Disney, it was a cute concept that seemed like it had that little nugget of potential, at the very least. At the time, we were trying to be a little more “hands-off” with our development projects and give them time to actually develop—funnily enough—before showing them to the entire executive team. So when Dan Povenmire wanted to pitch out the full storyboard instead of writing a script, we were all for it. The studio executive and I looked at the initial outline, gave a bit of feedback, and the next stage I saw was a full storyboard. It was the first time I know of at TVA [Disney Television Animation] that we'd ever seen an outline pitched with full storyboards, which impressed us because it really made sense for this show: having two lead characters that don't talk is hard to play in a script, and visual expression is vital to understanding what both Ferb and Perry the Platypus are all about. Dan and his co-creator Jeff “Swampy” Marsh had even written a theme song for the show, and that just further proved how deeply these creators knew their characters and how to present them effectively. Although this extensive a presentation is unusual and unexpected, it helped us fully grasp their vision for Phineas and Ferb and get behind it. The characters felt really fresh and had a soul to them. Plus, the board was really funny. That always helps.

During the pitch, it was clear that Dan and Swampy were more than prepared to survive the development process, as they had spent more than eleven years committed to making this property happen. This faith in their characters combined with their strong portfolio of experience around the industry made them appear to be the kind of team that we could get behind. As it turned out, we were right in our assessment. During development, they were good about being collaborative, and they were patient when they had to take notes from an ever-changing series of executives. They knew when to pick their battles and work within the process to get their vision onto the screen.

Figure 3-8 Phineas and Ferb (© Disney Channel).

It took Dan and Swampy a long time from when they first started to shop the project to when they got the green light at Disney. But if you asked them if it was worth it, I'm pretty sure they would say yes…especially now that they've got one of the most popular shows in the history of Disney Channel, an Emmy, multiple other awards and nominations, and an emerging franchise for the Walt Disney Company. Ideally, this tale of perseverance will keep you motivated to keep on pitching, so that you yourself can say enthusiastically, “Hey, Ferb, I know what we're gonna do today…we're gonna find the right buyer for our concept!”

Producers have to be smart and frugal about how to go about the process of developing on a budget, choosing wisely where to spend money and time when preparing for a pitch. If you believe that you have a strong story already, you may not need to spend money on creating original artwork but may instead rely on various reference looks from visuals already in existence.

Keep in mind at all times that the gestation period for a new idea has no defined schedule or path to success. What is consistent is the need to work and rework an idea over and over, poking holes into it and finding gaps. With every challenge come new solutions and ideas that can typically make a project better. If your project development process goes down a path that is not working, don't be afraid to throw out ideas and start again. Stepping back from an idea and putting it on the shelf for a while so that you can see it with fresh eyes is an effective way of evaluating your work. It is amazing what issues will become apparent and what great solutions come to mind when you give yourself the opportunity to create a healthy distance between yourself and your project. (See Chapter 5, “The Development Process,” for more details regarding the typical steps taken during full development of a project.)

Defining the Format and Target Audience

Once you have identified a property, it is important to determine its future format. Is it more suitable for a television series, theatrical features, direct-to-DVD, webisodes, gaming, or perhaps an iPhone/iPad application? If the answer is “more than one of these options,” that's great news, but in order to get started, make a decision based on the approach that is creatively and economically doable. Having a clear answer to this question up front will help you proceed with your pitch development efforts efficiently in terms of both time and money.

Figure 3–9 Toy Story 3 ((L–R) Slinky Dog, Aliens, Bullseye, Jessie, Mr. Potato Head, Woody, Mrs. Potato Head, Rex, Buzz Lightyear, Hamm. © 2010 Disney/Pixar. © Disney Enterprises, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Slinky ® Dig © James Industries. Mr. Potato Head ® and Mrs. Potato Head ® are registered trademarks of Hasbro, Inc. Used with Permission. © Hasbro, Inc. All Rights Reserved).

In the television arena, the target audience markets are very defined and niche, based on the demographics of the viewers and the network's brand. Ask yourself if the concept is aimed at a preschool, tween, teen, a prime-time audience, or is it best suited for adults only? If it is not clear who the viewer is, you may want to reconsider your choice or make defining it a top priority during development.

The audience for animated features is generally much broader. Unlike television, the target audience for feature properties developed by the larger studios tends to include both children and adults, as the success of Happy Feet and the Toy Story films (Figure 3-9) attest. Similar to features, home entertainment projects are also developed for a broad audience, but the lion's share of that market is children or, more specifically, parents buying DVDs for their young children.

Although large studios tend to develop for a broad marketplace, animated features can also be targeted at a more specific audience while maximizing a lower budget and wisely directing marketing efforts to that desired viewing segment. Independent producers have found ways to produce more niche, lower-budget films thanks to direct distribution outlets and viral marketing efforts. Films such as The Secret of Kells (Figure 3-10) and Nina Paley's passion project Sita Sings the Blues (Figure 3-11) have achieved critical success with much lower budgets than those of the typical major studio release.

Figure 3–10 The Secret of Kells (© 2009 Cartoon Saloon).

Figure 3–11 Sita Sings the Blues (© Nina Paley 2008).

Identifying the Buyer

There are two different types of buyers. The first is a group with a distribution arm, such as a network, cable company, or movie studio. Typically, it is advantageous to sell your property directly to one of these outlets, as the distribution and ancillary support (licensing, marketing, etc.) are already in place. On the other hand, depending on the property and your background, it may make more sense to sell your idea to an independent production house and partner with them to get your property sold. Though independent production companies ultimately need to find distribution, they may have other strengths to offer. The advantage of working with an independent production house is twofold. First, such companies tend to be more accessible. Second, they can draw on their internal resources and experience to develop and prepare your project for pitching to targeted buyers. Depending on the size and reputation of the company, it may be able to provide deficit financing (production money used to supplement the license/production fees paid by the buyer). The independent production house could also be better equipped to turn a property into a franchise, in terms of enough time to give it the attention required to reach such a goal. Or it may own an animation facility that could actually produce and develop the project.

There are several ways to find potential buyers. It is up to you to do your homework to find and target them. Read industry magazines (such as Hollywood Reporter, Variety, and Animation Magazine, to name a few) that interview and highlight key executives to discover who's who and what they are buying. Another option is to browse the Internet for websites and blogs on the industry. Depending on where a buyer works (that is, a production company, studio, network, or cable company), he or she may have a different title. The most common titles are creative executive, development executive, current executive, and programming executive. Whatever they are called, the buyers' overall responsibilities are generally the same. Their goal is to identify new and one-of-a-kind concepts to develop for the company. Their success is based on getting projects greenlit, produced, and—most important—turned into a hit. It is therefore vital that they seek out the material to be the next highly sought-after property that audiences want to see.

Once you have a solid pitch, don't be shy to pick up the phone and cold call. With that said, again, make sure to have done your homework to find out what type of development materials your potential buyer is seeking. Some studios require a fully fleshed out script; others are more open to a treatment and initial characters only. Each set of executives has their own personal approach to how they find and develop properties, so be sure to tailor your pitch to address their needs. Once a project has been selected, it is the job of the executives to shepherd it through the negotiation, development, and—in most cases—production processes.

Creative/Development Executives

The responsibilities assigned to an executive vary from one studio to another, as do titles. In some studios, for example, the development executive may work on a project's conceptual phase and remain equally involved as it goes through production, postproduction, and final delivery. Elsewhere, when a project has completed development and is greenlit for production, another executive inherits responsibility for the project from the development executive. In television, this position is commonly referred to as a current executive. In this type of structure, after a brief transition period during which both the current executive and the development executive are jointly involved, the current executive takes over the show. From this point on, the current executive manages its creative progress until the completion of production. For the sake of simplicity and clarity, we refer to the key creative point person on the buyer's side as the creative executive.

In terms of titles, a person with the creative executive title is typically in a more junior position within the studio hierarchy. This junior executive is probably the most accessible person amongst the development staff, as it is his or her job to be a gatekeeper while finding and sorting through ideas to share with the more senior members of the team. As you go up the ladder, there is a director, followed by a senior director (depending on the company), and then the vice president, senior vice president, and so on. The higher the person is, the more responsibility is placed on his or her shoulders in terms of having the power to option projects. Ultimately, the person in this position can decide how much money is allocated to the various phases of development and also whether it is beneficial to attach specific talent to the project. The more senior the person is, generally the tougher he or she is to access—unless, of course, you are already established in the business. With that in mind, another person that is generally approachable is the assistant to the executive. The assistant is usually a good person to befriend, as he or she can be a great source of information, possibly letting you know what the executive is looking for as well as getting you a meeting with him or her.

The creative executives' primary role is to identify properties for the company to pursue. They spend their time looking at all kinds of materials, including published works and original concepts. In their widespread search for talent, they attend film festivals; meet and foster relationships with writers, publishers, and agents; visit comedy clubs; and view postings on the Internet. They need to be in touch with what's hot, be able to recognize upcoming trends, and also possess a good sense of timing so as to jump on an idea before it is otherwise taken. Along with searching for properties, creative executives meet with producers, directors, and creators to take pitches and find material. In general, having an open-door policy allows the executive to listen to many pitches, therefore improving the probability of finding a hit. Once he or she has found something of interest, it is this executive's job to sell the property to his or her supervisor, for development and ultimately for production. The person they report to is typically the head of programming for the studio—the individual who has the ability to purchase or greenlight a project and put the necessary funds behind it.

The creative executive on your project is an integral part of the process in terms of championing your project forward. Depending on their level of seniority, they may not be individually able to greenlight the project, but if they believe in it, they have the power to keep your project alive by selling it to key individuals within their company, giving it the best chance for production. It is therefore your job as a producer to ensure that their initial enthusiasm for your story continues throughout the lengthy and often bumpy process of development.

During development, creative executives are very involved in finding and hiring the core team for a project, bringing together the director, producer, artists, writers, production designer, and art director. Once a project is in production, the executive monitors its creative progress to ensure that the story is working. Depending on the budget, schedule, and deal struck by the producer, these executives have input at key creative checkpoints throughout the process with regards to story, character development, and art direction. Should your project get produced, the creative executives are often very involved in getting it promoted both internally on a corporate level and externally to the public, thereby helping to secure its success. Finding ways to give the project as much exposure as possible is key not just for the sake of the show, but also for the future of the executive and his or her career.

Production Executive

When a project is close to being greenlit for production, another key executive is included in the process of analyzing whether it can actually be produced or not. This is the production executive. It is the production executive's job to assess whether the agreed-upon creative goals of a project can be achieved within the fiscal parameters of the production. In most cases, production executives report to the head of production.

The production executive works closely with the creative executive and the producer to structure a budget and schedule for both the development and production processes. Once a project begins actual production, the production executive monitors its progress, making certain that the creative needs of the buyer are served while meeting the agreed-upon schedule, budget, and delivery requirements. When a production has problems such as falling behind schedule, it is the role of the production executive to troubleshoot the situation, working with the producing team and creative executive to find solutions and get the production back on track.

Developing Pitch Material

It cannot be stressed enough how important it is to research your potential buyer and determine exactly what type of materials they want to see. As noted earlier, some buyers may be interested in a fully developed concept with a completed script and visuals, whereas others may only wish to see a premise and some rough designs. It may also depend on the profile of the project. If it is a well-known franchise, little or no development may be necessary to sell a project to a distributor (who will then partner with you to develop the material to suit their brand and market requirements). Many different approaches can be equally effective; it all depends on your concept and the would-be buyer.

When preparing, bear in mind that people can only take in so much before you start to lose them; therefore, keep the materials concise. No matter what form of pitch you choose, the three key elements to have in place are:

- The concept(s)

- The character(s)

- The story

For television, there are two main factors to set up from the start: a clear concept and a defined target audience. You should be able to explain what the series is about in a logline, meaning one or two sentences. Make sure you can communicate what sets this show apart from all of the others out in the marketplace. You must also have several compelling stories prepared in order to illustrate that the property has a life beyond the pilot episode (the first episode of a TV series) and that there is a reason why viewers would select this show over other choices. In most cases, if it is an original prime-time property, it is best to have a pilot script prepared. Keep in mind that if the network goes forward with optioning the property, it will probably do further development to the materials to shape the project for its specific audience.

For long-form properties such as feature films, you should be able to take the buyer through the main storyline using the classic structure of a beginning, middle, and end, presenting it in a concise and exciting way that will hook your audience. Introduce the main characters and a few supporting characters as you come to them in the process of pitching the story rather than up front. Be prepared to explain the subplots when questions arise, but don't try to include them in the main story pitch, as you want the story to be crystal-clear. If the property requires it, outline the rules of the universe: for example, do humans and animals interact? Define the target audience and describe the tone using frames of reference such as other movies or well-known stories. Artwork is not vital; however, a few carefully selected quality setups illustrating the characters in their world can be useful. You can flesh out your characters by selecting a few actors that might be considered for voice-over; however, do this sparingly and only if the project warrants it. If a composer is already attached (although this is not at all necessary), have a demo available. It is good to have a brief synopsis containing only the key story beats prepared to leave behind or to send as a follow-up. Prior to pitching, do not feel that you need to have ancillary partners such as merchandising in place. This aspect of the process is usually handled later on, and is not vital to the success of a pitch: in fact, if it is approached as a key focus in your pitch, it can be distracting to the buyer. However, if the property has transmedia opportunities (multiple formats to which the characters naturally lend themselves, such as gaming, web shorts, etc.) in addition to the format you are pitching, you should be prepared to cover all options. Depending on the buyer, having a business partner can be helpful, but at this stage, the main goal is to sell the idea on its own merit. For feature film executives, a strong story concept that fits with their studio's overall mandate is likely to work best. If all of these pieces fall into place, and the pitch holds up to their questions, an executive will want to pursue the project.

Pitching

Before going into a pitch, practice your presentation. First impressions are important, so it is critical to come off as polished and professional as possible. Brief is best. You should have the pitch down to ten minutes or under for a series and ten to fifteen minutes for a feature—no more! In both cases, it is a good technique to come up with a sentence that sets the tone of the pitch and provides context for your audience. This sentence may be as simple as referencing a well-known movie or story or combination of ideas to which your project is similar. If you have a creative partner, decide who will handle what during your meeting. Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of the partnership. Your strength may be in drawing and your partner's in selling the story. Take practice runs, setting each other up rather than stepping on top of one another during the presentation.

When pitching, try to remain as natural as possible. Analyze your audience's response and try to cater to what their needs are rather than taking the pitch in a direction that is suitable for you. Again, be short and to the point—don't waste time. Summarize what you are selling and get the concept across in just a few sentences.

Note that some studios may require you to sign a submission release agreement before you pitch to them. The purpose of this is to make clear the studio's position of no obligation to a producer by virtue of hearing a pitch, even holding the company harmless if the studio develops a project based on ideas similar to those pitched. This release is typically required for those people who have original ideas and are not established in the industry. However, in some cases, even the most established producer will be required to sign one of these agreements before he or she is allowed to pitch an idea.

Post Pitch

After a pitch, it generally takes time to get a response. Creative executives have many projects that cross their desks each week. Consequently, it is almost impossible for them to get back to everyone in a timely manner. Unless you meet with the person who can greenlight optioning a property, the creative executive still needs to sell it to his or her superiors, who may want you to pitch the property again directly to them. They may also ask you to send more materials. After the pitch, being patient is critical. You should expect to wait at least four weeks before hearing anything.

If this isn't the project for this executive, take the rejection gracefully. You want to leave a good impression with your executive so that he or she will want to see you again, at this job or the next, because executives tend to move around a lot. (It has been said that the average career span of a creative executive at a particular studio is between one-and-a-half to three years.) If you are in it for the long haul, chances are good that you will cross paths with this individual numerous times at different studios. If you get a positive response, you should be very excited, as you are one step closer to the fun process of in-depth development. But first you need to put an agreement in place with your new creative partner.

Hiring Representation

Whenever possible, it is advantageous to have a lawyer or an agent on your team when you pitch your project. As a company policy, some executives may not even meet with you or review a property unless you have representation. Executives prefer that the creator and/or producer be attached to a lawyer or agent for a number of reasons. The existence of these relationships helps avoid any potential misunderstandings when a similar project is greenlit or put into development. If the executive decides to option the property, you will be in the position to make a deal immediately. It also indicates that your material has been reviewed by an industry professional who is confident that the material is developed appropriately and is ready for pitching.

If you do not already have representation, the best way to find a lawyer or an agent is through recommendations. Speak to other artists or producers who can lead you in the right direction. If you do not have any connections, review the various animation journals (see the Appendix, “Animation Resources”) or research online directories such as the Animation Industry Database (http://www.aidb.com) to help you identify potential candidates. In order to make sure that you are hiring the right person, consider interviewing a few people. Your agent or lawyer is ultimately a reflection of you and your style. Because they represent you to the people with whom you are going to be working, you want to be sure that the relationship is solid when the project begins development. General questions to ask potential representation include:

- How long have you been in the business?

- What is your business philosophy?

- What is your negotiation style?

- Could you provide me with a list of clients?

- What are your rates?

- What is your method of payment?

It is necessary to set up the terms of your relationship with your representation before you go forward with negotiations on your project. As a rule of thumb, agents take 10 percent of the fees they negotiate, and entertainment lawyers are paid an hourly fee ranging from $300 to $900 per hour. The advantage of hiring a lawyer who is paid on an hourly basis is that once you have paid the fees, there are no additional costs. Some lawyers will charge a flat fee for negotiating a contract; however, most prefer to work on a percentage basis, which typically translates to 5 percent of your entire deal. In this case, the lawyer's payment is similar to an agent who is entitled to a percentage of the backend benefits. (Backend is a percentage of profits you receive on items such as domestic and international sales, spin-off projects, and merchandising.) The advantage of this type of contract is that because your agent or lawyer shares the financial rewards with you, he or she is highly motivated to get you the best deal possible. Also, if you hire an agent, you do not need to pay any fees until the buyer pays you. Another plus to working with an agent is that he or she can be instrumental in finding new opportunities for you as executives call agents when looking for talent. When selecting an agency or a lawyer, also consider the pros and cons of how big a pool of talent they serve. If you are new to the business, sometimes it makes more sense to find a representative with fewer clients so that you don't get lost in the shuffle.

Standing Out in a Crowd

Julie Kane-Ritsch, Manager, The Gotham Group

Although success in the entertainment business hinges on a combination of talent, tenacity, and timing, we decide whether to represent an artist or writer by assessing the talent portion of the equation. The single most important factor we look for is a distinctive voice. The second most important factor is whether the potential client has solid interpersonal skills. Creators most likely to flourish in the business are those who can interact successfully with executives and inspire a crew.

How do we assess talent? For a writer, we look for a unique voice. The only way to evaluate a writer's voice is to see it on the page. Therefore, we prefer to read original scripts, with a backup of spec scripts in the genre in which the client wants to focus. The original script can be a play, a half-hour episode, an hour episode, an animated piece, or a feature, and can be in the comedy, family film, thriller, or drama genres. The piece must have the prerequisites of a solid structure, coherent plot, and great characters, but the attention-grabbing factor is in the story the writer chooses to tell and how the writer chooses to tell it. With a strong original sample or two in hand, the writer must also have spec scripts to show that he or she can mimic another creator's voice. If a writer wants to write for an animated comedy, action/comedy animated series, or live-action comedy, the writer needs spec scripts in each of these arenas. In short, write as much and as often as possible.

For an artist, we look for the combination of a unique visual style or a distinctive vision expressed through words and visuals. If an artist ultimately wants to create television series or direct a feature, the strongest calling card is a short film. Students frequently create a beautifully rendered world in their film projects but fail to couple it with a cohesive and compelling story. These works rarely land an artist representation or a job. Shorts that are well executed with a strong story are the most memorable and impressive. If the story has a strong comedic sense, so much the better, as the majority of work done in the animation field is not seriously dramatic in nature. If an artist wants to focus on opportunities in the purely visual realm, a portfolio showing a signature style is critical. If the artist also has a broader range of styles and can mimic others, these pieces should be showcased as well.

How do we assess interpersonal skills? It all comes down to the meeting. How at ease is she in a room? Can he pitch his ideas effectively? What do her professors or bosses say about her? Do his peers want to work with him again? Based on a meeting or two with the potential client and talking to bosses and co-workers, we can form a fairly good picture of the person's interpersonal skill set. This knowledge is essential in making a representation decision. Even if an artist or writer has all the talent in the world, animation is an incredibly collaborative process and, by necessity, requires constant interaction with others. An artist must be able to effectively deal with executives, who will be giving notes, setting schedules, and approving budget requests, and who will be involved in the day-to-day realities of production. Not only must an artist manage up to those people who will finance and distribute his or her work, but the artist must also manage down to inspire the confidence and creativity in a crew. Few people embody all of these skills equally, and part of our evaluation is whether we think these skills can be developed.

We enjoy nothing more than finding the creator who makes us laugh, who makes us shudder, or who makes us wonder at the worlds he or she creates. Once we find these creative individuals, our job is to tenaciously pursue their career objectives and to maximize the timing of opportunities presented to them in the business. It is an exciting and a rewarding collaboration in which we are privileged to participate.

Entering Negotiations

Patience is vital when heading into the negotiation process. After everyone has agreed that they would be interested in developing a property together, it goes into the world of “business affairs,” where the attorneys work out the deal points to option the property. These negotiations can average three to nine months before all parties are in agreement and the contract is finalized. The exception to this rule would be if the project is on the “fast track” and someone in a decision-making position is interested enough in it to make it a top priority.

Many steps take place internally (meaning at the buyer's place of business) in order for everyone to agree to the costs involved in developing and producing a property. Once internal meetings take place, the buyer's business affairs person will make an offer to your representative. After the offer has been presented, it is up to you and your representative to counter the proposal. In order to do this, you need to think about what is important to you in the deal and what is not. After discussing this with your representative, he or she will go back to the buyer with a counteroffer. This back-and-forth negotiating process continues until everyone agrees to terms that are satisfactory to all parties.

A short-form contract is negotiated first, and then a long-form contract is drawn up. The short-form contract typically spells out the key deal points, including:

- Option fees

- Compensation

- Services to be rendered (that is, producing, writing, and so on)

- The term (the length of the option period, or how long the project can be kept at the studio before it is greenlit or released back into the possession of the producer)

- Backend percentages

- Credits

- Ownership

- Purchase price of the project once production is commenced

- Transmedia options (if applicable)

The long-form contract is a detailed legal document that includes all of the material stipulations negotiated in the shortform contract, as well as terms that are standard and customary in the industry. These conditions include representation and warranties, termination, indemnification, and force majeure, for example. In most cases, they are nonnegotiable terms. The studio's backend definition is usually attached as a rider to the long form. This type of rider is an additional contract that defines all of the complex details regarding the calculation process that a studio will undertake before sharing in the profits of a successful project. This document is typically quite lengthy and is not usually written in a way that is simple to negotiate or easily understood. Unless you have ample resources, you will need to determine whether to spend the money to have someone review this material. You will also need to assess whether you have the clout in terms of your personal or your property's perceived value to shift the definition provided by the studio in a way that will fiscally benefit you and offset the investment to do this.

When negotiating your deal, be realistic in your expectations. You are probably not going to get everything on your wish list. Negotiating entails compromise. Your representative should be able to provide you with current market rates as a frame of reference. By thoroughly considering all options offered, you should be able to make educated decisions as you forge through this process. Various factors—including your experience, the buyer's policies, standard negotiation practices, and the studio precedents—can place the final results somewhat out of your control. It is essential that you feel satisfied enough with the deal so that you can work with enthusiasm on the development of the project. However, try to be flexible, and when you do give in on a point, let it go and move on. It is important to preserve the relationship and keep good will intact on the part of your buyer. After all, once the negotiations are completed, you will be working together on the same team.

Once agreements have been signed, development can begin.