22 Generating Images

ONE OF THE USEFUL THINGS YOU CAN DO WITH PHP is create images on the fly. PHP has some built-in image information functions, and you can also use the GD2 library to create new images or manipulate existing ones. This chapter discusses how to use these image functions to achieve some interesting and useful effects.

Key topics covered in this chapter include

![]() Setting up image support in PHP

Setting up image support in PHP

![]() Using automatically generated images in other pages

Using automatically generated images in other pages

![]() Using text and fonts to create images

Using text and fonts to create images

![]() Drawing figures and graphing data

Drawing figures and graphing data

Specifically, we look at two examples: generating website buttons on the fly and drawing a bar chart using figures from a MySQL database.

We use the GD2 library here, but there is one other popular PHP image library. The ImageMagick library is not part of the standard PHP build but is easily installable from the PHP Extension Class Library (PECL). ImageMagick and GD2 have a lot of fairly similar features, but in some areas ImageMagick goes further. If you want to create GIFs (even animated GIFS), you should look at ImageMagick. If you want to work with true color images or render transparent effects, you should compare the offerings in both libraries.

See PECL for the PHP download of ImageMagick at http://pecl.php.net/package/imagick.

See the main ImageMagick site for demonstrations of its capabilities and detailed documentation at http://www.imagemagick.org.

Setting Up Image Support in PHP

Some of the image functions in PHP are always available, but most of them require the GD2 library. Detailed information about GD2 is available at http://www.libgd.org/Main_Page.

Since PHP 4.3, PHP comes with its own forked version of the GD2 library, supported by the PHP team. This version is easier to install with PHP and is usually more stable, so it’s advisable to use this version. Under Windows, PNGs and JPEGs are automatically supported as long as you have the php_gd2.dll extension registered. You can do this by copying the php_gd2.dll file from your PHP installation directory (in the ext subfolder) to your system directory (the C:Windowssystem directory if using Windows XP). You must also uncomment the following line in your php.ini file by removing the “;” at the beginning of the line:

extension=php_gd2.dll

If you have Unix and want to work with PNGs, you need to install libpng from http://www.libpng.org/pub/png/ and zlib from http://www.gzip.org/zlib/.

You then need to configure PHP with the following options:

--with-png-dir=/path/to/libpng

--with-zlib-dir=/path/to/zlib

If you have Unix and want to work with JPEGs, you need to download jpeg-6b and recompile GD with JPEG support included. You can download it from ftp://ftp.uu.net/graphics/jpeg/.

You then need to reconfigure PHP with the following option and recompile it:

--with-jpeg-dir=/path/to/jpeg-6b

If you want to use TrueType fonts in your images, you also need the FreeType library. It also comes with PHP since version 4. Alternatively, you can download it from http://www.freetype.org/.

If you want to use PostScript Type 1 fonts instead, you need to download t1lib, available from ftp://sunsite.unc.edu/pub/Linux/libs/graphics/.

You then need to run PHP’s configure program with

--with-t1lib[=path/to/t1lib]

Finally, you will, of course, need to configure PHP using --with-gd.

Understanding Image Formats

The GD library supports JPEG, PNG, and WBMP formats. It no longer supports the GIF format. Let’s briefly look at each of these formats.

JPEG

JPEG (pronounced “jay-peg”) stands for Joint Photographic Experts Group and is really the name of a standards body, not a specific format. The file format we mean when we refer to JPEGs is officially called JFIF, which corresponds to one of the standards issued by JPEG.

In case you are not familiar with them, JPEGs are usually used to store photographic or other images with many colors or gradations of color. This format uses lossy compression; that is, to squeeze a photograph into a smaller file, some image quality is lost. Because JPEGs should contain what are essentially analog images, with gradations of color, the human eye can tolerate some loss of quality. This format is not suitable for line drawings, text, or solid blocks of color.

You can read more about JPEG/JFIF at the official JPEG site at http://www.jpeg.org/.

PNG

PNG (pronounced “ping”) stands for Portable Network Graphics. This file format is the replacement for GIF (Graphics Interchange Format) for reasons we discuss shortly. The PNG website describes it as “a turbo-studly image format with lossless compression.” Because it is lossless, this image format is suitable for images that contain text, straight lines, and blocks of color such as headings and website buttons—all the same purposes for which you previously might have used GIFs. A PNG-compressed version of the same image is generally similar in size to a GIF-compressed version. PNG also offers variable transparency, gamma correction, and two-dimensional interlacing. It does not, however, support animations; for this, you must use the extension format MNG, which is still in development.

Lossless compression schemes are good for illustrations but not generally a good way to store large photos because they tend to give large file sizes.

You can read more about PNG at the official PNG site at http://www.libpng.org/pub/png/.

WBMP

WBMP, which stands for Wireless Bitmap, is a file format designed specifically for wireless devices. It is not in wide use.

GIF

GIF stands for Graphics Interchange Format. It is a compressed lossless format widely used on the Web for storing images containing text, straight lines, and blocks of single color.

The GIF format uses a palette of up to 256 distinct colors from the 24-bit RGB color space. It also supports animations, allowing a separate palette of 256 colors for each frame. The color limitation makes the GIF format unsuitable for reproducing color photographs and other images with continuous color, but it is well-suited for more simple images such as graphics or logos with solid areas of color.

GIFs are compressed using the LZW lossless data compression technique, which reduces the file size without degrading the visual quality.

Creating Images

The four basic steps to creating an image in PHP are as follows:

1. Creating a canvas image on which to work.

2. Drawing shapes or printing text on that canvas.

3. Outputting the final graphic.

4. Cleaning up resources.

Let’s begin by looking at the simple image creation script shown in Listing 22.1.

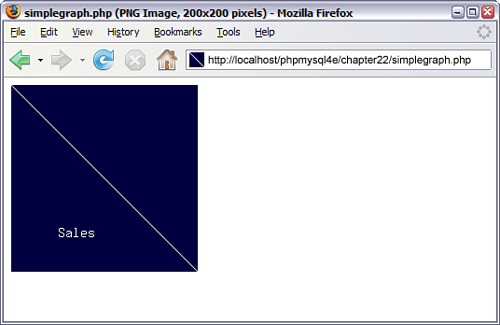

Listing 22.1 simplegraph.php—Outputs a Simple Line Graph with the Label Sales

<?php

// set up image

$height = 200;

$width = 200;

$im = imagecreatetruecolor($width, $height);

$white = imagecolorallocate ($im, 255, 255, 255);

$blue = imagecolorallocate ($im, 0, 0, 64);

// draw on image

imagefill($im, 0, 0, $blue);

imageline($im, 0, 0, $width, $height, $white);

imagestring($im, 4, 50, 150, 'Sales', $white);

// output image

Header ('Content-type: image/png'),

imagepng ($im);

// clean up

imagedestroy($im);

?>

The output from running this script is shown in Figure 22.1.

Figure 22.1 The script draws a blue background and then adds a line and a text label for the image.

Now let’s walk through the steps of creating this image one by one.

Creating a Canvas Image

To begin building or changing an image in PHP, you need to create an image identifier. There are two basic ways to do this. One is to create a blank canvas, which you can do with a call to the imagecreatetruecolor() function, as done in this script with the following:

$im = imagecreatetruecolor($width, $height);

You need to pass two parameters to ImageCreateTrueColor(). The first is the width of the new image, and the second is the height of the new image. The function will return an identifier for the new image. These identifiers work a lot like file handles.

An alternative way is to read in an existing image file that you can then filter, resize, or add to. You can do this with one of the functions imagecreatefrompng(), imagecreatefromjpeg(), or imagecreatefromgif(), depending on the file format you are reading in. Each of these functions takes the filename as a parameter, as in this example:

$im = imagecreatefrompng('baseimage.png'),

An example is shown later in this chapter using existing images to create buttons on the fly.

Drawing or Printing Text on the Image

Drawing or printing text on the image really involves two stages. First, you must select the colors in which you want to draw. As you probably already know, colors to be displayed on a computer monitor are made up of different amounts of red, green, and blue light. Image formats use a color palette that consists of a specified subset of all the possible combinations of the three colors. To use a color to draw in an image, you need to add this color to the image’s palette. You must do this for every color you want to use, even black and white.

You can select colors for your image by calling the ImageColorAllocate() function. You need to pass your image identifier and the red, green, and blue (RGB) values of the color you want to draw into the function.

Listing 22.1 uses two colors: blue and white. You allocate them by calling

$white = imagecolorallocate ($im, 255, 255, 255);

$blue = imagecolorallocate ($im, 0, 0, 64);

The function returns a color identifier that you can use to access the color later.

Second, to actually draw into the image, you can use a number of different functions, depending on what you want to draw—lines, arcs, polygons, or text.

The drawing functions generally require the following as parameters:

![]() The image identifier

The image identifier

![]() The start and sometimes the end coordinates of what you want to draw

The start and sometimes the end coordinates of what you want to draw

![]() The color you want to draw in

The color you want to draw in

![]() For text, the font information

For text, the font information

In this case, you use three of the drawing functions. Let’s look at each one in turn.

First, you paint a blue background on which to draw using the imagefill() function:

imagefill($im, 0, 0, $blue);

This function takes the image identifier, the start coordinates of the area to paint (x and y), and the color to fill in as parameters.

Next, you draw a line from the top-left corner (0, 0) to the bottom-right corner ($width, $height) of the image:

imageline($im, 0, 0, $width, $height, $white);

This function takes the image identifier, the start point x and y for the line, the end point, and then the color as parameters.

Finally, you add a label to the graph:

imagestring($im, 4, 50, 150, 'Sales', $white);

The imagestring() function takes some slightly different parameters. The prototype for this function is

int imagestring (resource im, int font, int x, int y, string s, int col)

It takes as parameters the image identifier, the font, the x and y coordinates to start writing the text, the text to write, and the color.

The font is a number between 1 and 5. These numbers represent a set of built-in fonts in latin2 encoding, with higher numbers corresponding to larger fonts. As an alternative to these fonts, you can use TrueType fonts or PostScript Type 1 fonts. Each of these font sets has a corresponding function set. We use the TrueType functions in the next example.

A good reason for using one of the alternative font function sets is that the text written by imagestring() and associated functions, such as imagechar() (write a character to the image) is aliased. The TrueType and PostScript functions produce antialiased text.

If you’re not sure what the difference is, look at Figure 22.2. Where curves or angled lines appear in the letters, the aliased text appears jagged. The curve or angle is achieved by using a “staircase” effect. In the antialiased image, when curves or angles appear in the text, pixels in colors between the background and the text color are used to smooth the text’s appearance.

Figure 22.2 Normal text appears jagged, especially in a large font size. Antialiasing smoothes the curves and corners of the letters.

![]()

Outputting the Final Graphic

You can output an image either directly to the browser or to a file.

In this example, you output the image to the browser. This is a two-stage process. First, you need to tell the web browser that you are outputting an image rather than text or HTML. You do this by using the Header() function to specify the MIME type of the image:

Header ('Content-type: image/png'),

Normally, when you retrieve a file in your browser, the MIME type is the first thing the web server sends. For an HTML or PHP page (post execution), the first thing sent is

Content-type: text/html

This tells the browser how to interpret the data that follows.

In this case, you want to tell the browser that you are sending an image instead of the usual HTML output. You can do this by using the Header() function, which we have not yet discussed.

This function sends raw HTTP header strings. Another typical application of this function is to do HTTP redirects. They tell the browser to load a different page instead of the one requested. They are typically used when a page has been moved. For example,

Header ('Location: http://www.domain.com/new_home_page.html'),

An important point to note when using the Header() function is that it cannot be executed if content has already been sent for the page. PHP will send an HTTP header automatically for you as soon as you output anything to the browser. Hence, if you have any echo statements, or even any whitespace before your opening PHP tag, the headers will be sent, and you will get a warning message from PHP when you try to call Header(). However, you can send multiple HTTP headers with multiple calls to the Header() function in the same script, although they must all appear before any output is sent to the browser.

After you have sent the header data, you output the image data with a call to

imagepng ($im);

This call sends the output to the browser in PNG format. If you wanted it sent in a different format, you could call imagejpeg()—if JPEG support is enabled. You would also need to send the corresponding header first, as shown here:

Header ('Content-type: image/jpeg'),

The second option you can use, as an alternative to all the previous ones, is to write the image to a file instead of to the browser. You can do this by adding the optional second parameter to imagepng() (or a similar function for the other supported formats):

imagepng($im, $filename);

Remember that all the usual rules about writing to a file from PHP apply (for example, having permissions set up correctly).

Cleaning Up

When you’re done with an image, you should return the resources you have been using to the server by destroying the image identifier. You can do this with a call to imagedestroy():

imagedestroy($im);

Using Automatically Generated Images in Other Pages

Because a header can be sent only once, and this is the only way to tell the browser that you are sending image data, it is slightly tricky to embed any images you create on the fly in a regular page. Three ways you can do it are as follows:

![]() You can have an entire page consist of the image output, as we did in the previous example.

You can have an entire page consist of the image output, as we did in the previous example.

![]() You can write the image out to a file, as previously mentioned, and then refer to it with a normal

You can write the image out to a file, as previously mentioned, and then refer to it with a normal <IMG> tag.

![]() You can put the image production script in an image tag.

You can put the image production script in an image tag.

We have covered the first two methods already. Let’s briefly look at the third method now. To use this method, you include the image inline in HTML by having an image tag along the lines of the following:

<img src="simplegraph.php" height="200" width="200" alt="Sales going down" />

Instead of putting in a PNG, JPEG, or GIF directly, put in the PHP script that generates the image in the SRC tag. It will be retrieved and the output added inline, as shown in Figure 22.3.

Figure 22.3 The dynamically produced inline image appears the same as a regular image to the end user.

Using Text and Fonts to Create Images

Let’s look at a more complicated example of creating images. It is useful to be able to create buttons or other images for your website automatically. You can easily build simple buttons based on a rectangle of background color using the techniques we’ve already discussed. You can generate more complicated effects programmatically, too, but you can generally do it more easily in a paint program. This also makes it easier to get an artist to do the artwork and leave programmers programming.

In this example, you generate buttons using a blank button template. This allows you to have features such as beveled edges and so on, which are a good deal easier to generate using Photoshop, the GIMP, or some other graphics tool. With the image library in PHP, you can begin with a base image and draw on top of that.

You also use TrueType fonts in this example so that you can use antialiased text. The TrueType font functions have their own quirks, which we discuss.

The basic process is to take some text and generate a button with that text on it. The text will be centered both horizontally and vertically on the button, and will be rendered in the largest font size that will fit on the button.

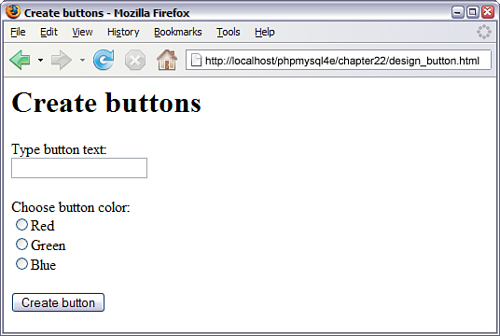

We built a front end to the button generator for testing and experimenting. This interface is shown in Figure 22.4. (We did not include the HTML for this form here because it is very simple, but you can find it on the CD in design_button.html.)

Figure 22.4 The front end lets a user choose the button color and type in the required text.

You could use this type of interface for a program to automatically generate websites. You could also call the script in an inline fashion, to generate all a website’s buttons on the fly, but this would require caching to stop it becoming time consuming.

Typical output from the script is shown in Figure 22.5.

Figure 22.5 This button is generated by the make_button.php script.

The button is generated by the make_button.php script shown in Listing 22.2.

Listing 22.2 make_button.php—Enables Calls from the Form in design_button.html or from Within an HTML Image Tag

<?php

// check we have the appropriate variable data

// variables are button-text and color

$button_text = $_REQUEST['button_text'];

$color = $_REQUEST['color'];

if (empty($button_text) || empty($color))

{

echo 'Could not create image - form not filled out correctly';

exit;

}

// create an image of the right background and check size

$im = imagecreatefrompng ($color.'-button.png'),

$width_image = imagesx($im);

$height_image = imagesy($im);

// Our images need an 18 pixel margin in from the edge of the image

$width_image_wo_margins = $width_image - (2 * 18);

$height_image_wo_margins = $height_image - (2 * 18);

// Work out if the font size will fit and make it smaller until it does

// Start out with the biggest size that will reasonably fit on our buttons

$font_size = 33;

// you need to tell GD2 where your fonts reside

putenv('GDFONTPATH=C:WINDOWSFonts'),

$fontname = 'arial';

do

{

$font_size--;

// find out the size of the text at that font size

$bbox=imagettfbbox ($font_size, 0, $fontname, $button_text);

$right_text = $bbox[2]; // right co-ordinate

$left_text = $bbox[0]; // left co-ordinate

$width_text = $right_text - $left_text; // how wide is it?

$height_text = abs($bbox[7] - $bbox[1]); // how tall is it?

}

while ( $font_size>8 &&

( $height_text>$height_image_wo_margins ||

$width_text>$width_image_wo_margins )

);

if ( $height_text>$height_image_wo_margins ||

$width_text>$width_image_wo_margins )

{

// no readable font size will fit on button

echo 'Text given will not fit on button.<br />';

}

else

{

// We have found a font size that will fit

// Now work out where to put it

$text_x = $width_image/2.0 - $width_text/2.0;

$text_y = $height_image/2.0 - $height_text/2.0 ;

if ($left_text < 0)

$text_x += abs($left_text); // add factor for left overhang

$above_line_text = abs($bbox[7]); // how far above the baseline?

$text_y += $above_line_text; // add baseline factor

$text_y -= 2; // adjustment factor for shape of our template

$white = imagecolorallocate ($im, 255, 255, 255);

imagettftext ($im, $font_size, 0, $text_x, $text_y, $white, $fontname,

$button_text);

Header ('Content-type: image/png'),

imagepng ($im);

}

imagedestroy ($im);

?>

This is one of the longest scripts we’ve looked at so far. Let’s step through it section by section. The script begins with some basic error checking and then sets up the canvas on which you’re going to work.

Setting Up the Base Canvas

In Listing 22.2, instead of starting from scratch, you start with an existing image for the button. You provide a choice of three colors in the basic button: red (red-button.png), green (green-button.png), and blue (blue-button.png).

The user’s chosen color is stored in the color variable from the form.

You begin by extracting the color from the superglobal $_REQUEST and setting up a new image identifier based on the appropriate button:

$color = $_REQUEST['color'];

…

$im = imagecreatefrompng ($color.'-button.png'),

The function imagecreatefrompng() takes the filename of a PNG as a parameter and returns a new image identifier for an image containing a copy of that PNG. Note that this does not modify the base PNG in any way. You can use the imagecreatefromjpeg() and imagecreatefromgif() functions in the same way if the appropriate support is installed.

Fitting the Text onto the Button

Some text typed in by the user is stored in the $button_text variable. What you need to do is print that text on the button in the largest font size that will fit. You do this by iteration, or strictly speaking, by iterative trial and error.

You start by setting up some relevant variables. The first two are the height and width of the button image:

$width_image = imagesx($im);

$height_image = imagesy($im);

The second two represent a margin in from the edge of the button. The button images are beveled, so you need to leave room for that around the edges of the text. If you are using different images, this number will be different! In this case, the margin on each side is around 18 pixels:

$width_image_wo_margins = $width_image - (2 * 18);

$height_image_wo_margins = $height_image - (2 * 18);

You also need to set up the initial font size. You start with 32 (actually 33, but you decrement that in a minute) because this is about the biggest font that will fit on the button at all:

$font_size = 33;

With GD2, you need to tell it where your fonts live by setting the environment variable GDFONTPATH as follows:

putenv('GDFONTPATH=C:WINDOWSFonts'),

You also set up the name of the font you want to use. You’re going to use this font with the TrueType functions, which will look for the font file in the preceding location and will append the filename with .ttf (TrueType Font):

$fontname = 'arial';

Note that depending on your operating system, you may have to add .ttf to the end of the font name.

If you don’t have Arial (the font we used here) on your system, you can easily change it to another TrueType font.

Now you loop, decrementing the font size at each iteration, until the submitted text will fit on the button reasonably:

do

{

$font_size--;

// find out the size of the text at that font size

$bbox=imagettfbbox ($font_size, 0, $fontname, $button_text);

$right_text = $bbox[2]; // right co-ordinate

$left_text = $bbox[0]; // left co-ordinate

$width_text = $right_text - $left_text; // how wide is it?

$height_text = abs($bbox[7] - $bbox[1]); // how tall is it?

}

while ( $font_size>8 &&

( $height_text>$height_image_wo_margins ||

$width_text>$width_image_wo_margins )

);

This code tests the size of the text by looking at what is called the bounding box of the text. You do this by using the imagegetttfbbox() function, which is one of the TrueType font functions. You will, after you have figured out the size, print on the button using a TrueType font (we used Arial, but you can use whatever you like) and the imagettftext() function.

The bounding box of a piece of text is the smallest box you could draw around the text. An example of a bounding box is shown in Figure 22.6.

Figure 22.6 Coordinates of the bounding box are given relative to the baseline. The origin of the coordinates is shown here as (0,0).

To get the dimensions of the box, you call

$bbox=imagettfbbox ($font_size, 0, $fontname, $button_text);

This call says, “For given font size $font_size, with text slanted on an angle of zero degrees, using the TrueType font Arial, tell me the dimensions of the text in $button_text.”

Note that you actually need to pass the path to the file containing the font into the function. In this case, it’s in the same directory as the script (the default), so we didn’t specify a longer path.

The function returns an array containing the coordinates of the corners of the bounding box. The contents of the array are shown in Table 22.1.

Table 22.1 Contents of the Bounding Box Array

To remember what the contents of the array are, just remember that the numbering starts at the bottom-left corner of the bounding box and works its way around counterclockwise.

There is one tricky thing about the values returned from the imagettfbbox() function. They are coordinate values, specified from an origin. However, unlike coordinates for images, which are specified relative to the top-left corner, they are specified relative to a baseline.

Look at Figure 22.6 again. You will see that we have drawn a line along the bottom of most of the text. This is known as the baseline. Some letters hang below the baseline, such as y in this example. These parts of the letters are called descenders.

The left side of the baseline is specified as the origin of measurements—that is, x coordinate 0 and y coordinate 0. Coordinates above the baseline have a positive x coordinate, and coordinates below the baseline have a negative x coordinate.

In addition, text might actually have coordinate values that sit outside the bounding box. For example, the text might actually start at an x coordinate of –1.

What this all adds up to is the fact that care is required when you’re performing calculations with these numbers.

You work out the width and height of the text as follows:

$right_text = $bbox[2]; // right co-ordinate

$left_text = $bbox[0]; // left co-ordinate

$width_text = $right_text - $left_text; // how wide is it?

$height_text = abs($bbox[7] - $bbox[1]); // how tall is it?

After you have this information, you test the loop condition:

} while ( $font_size>8 &&

( $height_text>$height_image_wo_margins ||

$width_text>$width_image_wo_margins )

);

You test two sets of conditions here. The first is that the font is still readable; there’s no point in making it much smaller than 8-point type because the button becomes too difficult to read. The second set of conditions tests whether the text will fit inside the drawing space you have available for it.

Next, you check to see whether the iterative calculations found an acceptable font size and report an error if not:

if ( $height_text>$height_image_wo_margins ||

$width_text>$width_image_wo_margins )

{

// no readable font size will fit on button

echo 'Text given will not fit on button.<br />';

}

Positioning the Text

If all was okay, you next work out a base position for the start of the text. This is the midpoint of the available space.

$text_x = $width_image/2.0 - $width_text/2.0;

$text_y = $height_image/2.0 - $height_text/2.0 ;

Because of the complications with the baseline relative coordinate system, you need to add some correction factors:

if ($left_text < 0)

$text_x += abs($left_text); // add factor for left overhang

$above_line_text = abs($bbox[7]); // how far above the baseline?

$text_y += $above_line_text; // add baseline factor

$text_y -= 2; // adjustment factor for shape of our template

These correction factors allow for the baseline and a little adjustment because the image is a bit “top heavy.”

Writing the Text onto the Button

After that, it’s all smooth sailing. You set up the text color, which will be white:

$white = ImageColorAllocate ($im, 255, 255, 255);

You can then use the imagettftext() function to actually draw the text onto the button:

imagettftext ($im, $font_size, 0, $text_x, $text_y, $white, $fontname,

$button_text);

This function takes quite a lot of parameters. In order, they are the image identifier, the font size in points, the angle you want to draw the text at, the starting x and y coordinates of the text, the text color, the font file, and, finally, the actual text to go on the button.

Finishing Up

Finally, you can output the button to the browser:

Header ('Content-type: image/png'),

imagepng ($im);

Then it’s time to clean up resources and end the script:

imagedestroy ($im);

That’s it! If all went well, you should now have a button in the browser window that looks similar to the one you saw in Figure 22.5.

Drawing Figures and Graphing Data

In the preceding application, we looked at existing images and text. We haven’t yet looked at an example with drawing, so let’s do that now.

In this example, you run a poll on your website to test whom users will vote for in a fictitious election. You store the results of the poll in a MySQL database and draw a bar chart of the results using the image functions.

Graphing is the other thing these functions are primarily used for. You can chart any data you want—sales, web hits, or whatever takes your fancy.

For this example, we spent a few minutes setting up a MySQL database called poll. It contains one table called poll_results, which holds the candidates’ names in the candidate column and the number of votes they received in the num_votes column. We also created a user for this database called poll, with password poll. This table is straightforward to set up, and you can create it by running the SQL script shown in Listing 22.3. You can do this piping the script through a root login using

mysql -u root -p < pollsetup.sql

Of course, you could also use the login of any user with the appropriate MySQL privileges.

Listing 22.3 pollsetup.sql—Sets Up the Poll Database

create database poll;

use poll;

create table poll_results (

candidate varchar(30),

num_votes int

);

insert into poll_results values

('John Smith', 0),

('Mary Jones', 0),

('Fred Bloggs', 0)

;

grant all privileges

on poll.*

to poll@localhost

identified by 'poll';

This database contains three candidates. You provide a voting interface via a page called vote.html. The code for this page is shown in Listing 22.4.

Listing 22.4 vote.html—Allows Users to Cast Their Votes Here

<html>

<head>

<title>Polling</title>

<head>

<body>

<h1>Pop Poll</h1>

<p>Who will you vote for in the election?</p>

<form method="post" action="show_poll.php">

<input type="radio" name="vote" value="John Smith">John Smith<br />

<input type="radio" name="vote" value="Mary Jones">Mary Jones<br />

<input type="radio" name="vote" value="Fred Bloggs">Fred Bloggs<br /><br />

<input type="submit" value="Show results">

</form>

</body>

</html>

The output from this page is shown in Figure 22.7.

The general idea is that, when users click the button, you will add their vote to the database, get all the votes out of the database, and draw the bar chart of the current results.

Typical output after some votes have been cast is shown in Figure 22.8.

Figure 22.7 Users can cast their votes here, and clicking the submit button will show them the current poll results.

Figure 22.8 Vote results are created by drawing a series of lines, rectangles, and text items onto a canvas.

The script that generates this image is quite long. We split it into four parts, and we discuss each part separately. Most of the script is familiar; you have seen many MySQL examples similar to this one. You looked at how to paint a background canvas in a solid color and how to print text labels on it.

The new parts of this script relate to drawing lines and rectangles. We focus our attention on these sections. Part 1 (of this four-part script) is shown in Listing 22.5.1.

Listing 22.5.1 show_poll.php—Part 1 Updates the Vote Database and Retrieves the New Results

<?php

/*******************************************

Database query to get poll info

*******************************************/

// get vote from form

$vote=$_REQUEST['vote'];

// log in to database

if (!$db_conn = new mysqli('localhost', 'poll', 'poll', 'poll'))

{

echo 'Could not connect to db<br />';

exit;

}

if (!empty($vote)) // if they filled the form out, add their vote

{

$vote = addslashes($vote);

$query = "update poll_results

set num_votes = num_votes + 1

where candidate = '$vote'";

if(!($result = @$db_conn->query($query)))

{

echo 'Could not connect to db<br />';

exit;

}

}

// get current results of poll, regardless of whether they voted

$query = 'select * from poll_results';

if(!($result = @$db_conn->query($query)))

{

echo 'Could not connect to db<br />';

exit;

}

$num_candidates = $result->num_rows;

// calculate total number of votes so far

$total_votes=0;

while ($row = $result->fetch_object())

{

$total_votes += $row->num_votes;

}

$result->data_seek(0); // reset result pointer

Part 1, shown in Listing 22.5.1, connects to the MySQL database, updates the votes according to the user’s selection, and gets the stored votes. After you have that information, you can begin making calculations to draw the graph. Part 2 is shown in Listing 22.5.2.

Listing 22.5.2 show_poll.php—Part 2 Sets Up All the Variables for Drawing

/*******************************************

Initial calculations for graph

*******************************************/

// set up constants

putenv('GDFONTPATH=C:WINDOWSFonts'),

$width=500; // width of image in pixels – this will fit in 640x480

$left_margin = 50; // space to leave on left of graph

$right_margin= 50; // ditto right

$bar_height = 40;

$bar_spacing = $bar_height/2;

$font = 'arial';

$title_size= 16; // point

$main_size= 12; // point

$small_size= 12; // point

$text_indent = 10; // position for text labels from edge of image

// set up initial point to draw from

$x = $left_margin + 60; // place to draw baseline of the graph

$y = 50; // ditto

$bar_unit = ($width-($x+$right_margin)) / 100; // one "point" on the graph

// calculate height of graph - bars plus gaps plus some margin

$height = $num_candidates * ($bar_height + $bar_spacing) + 50;

Part 2 sets up some variables that you will use to actually draw the graph.

Working out the values for these sorts of variables can be tedious, but a bit of fore-thought about how you want the finished image to look will make the drawing process much easier. We arrived at the values used here by sketching the desired effect on a piece of paper and estimating the required proportions.

The $width variable is the total width of the canvas you will use. You also set up the left and right margins (with $left_margin and $right_margin, respectively); the “fatness” and spacing between the bars ($bar_height and $bar_spacing); and the font, font sizes, and label position ($font, $title_size, $main_size, $small_size, and $text_indent).

Given these base values, you can then make a few calculations. You want to draw a baseline that all the bars stretch out from. You can work out the position for this baseline by using the left margin plus an allowance for the text labels for the x coordinate and again an estimate from the sketch for the y coordinate. You could get the exact width of the longest name instead if flexibility is important.

You also work out two important values: first, the distance on the graph that represents one unit:

$bar_unit = ($width-($x+$right_margin)) / 100; // one "point" on the graph

This is the maximum length of the bars—from the baseline to the right margin—divided by 100 because the graph is going to show percentage values.

The second value is the total height that you need for the canvas:

$height = $num_candidates * ($bar_height + $bar_spacing) + 50;

This value is basically the height per bar times the number of bars, plus an extra amount for the title. Part 3 is shown in Listing 22.5.3.

Listing 22.5.3 show_poll.php —Part 3 Sets Up the Graph, Ready for the Data to Be Added

/*******************************************

Set up base image

*******************************************/

// create a blank canvas

$im = imagecreatetruecolor($width,$height);

// Allocate colors

$white=imagecolorallocate($im,255,255,255);

$blue=imagecolorallocate($im,0,64,128);

$black=imagecolorallocate($im,0,0,0);

$pink = imagecolorallocate($im,255,78,243);

$text_color = $black;

$percent_color = $black;

$bg_color = $white;

$line_color = $black;

$bar_color = $blue;

$number_color = $pink;

// Create "canvas" to draw on

imagefilledrectangle($im,0,0,$width,$height,$bg_color);

// Draw outline around canvas

imagerectangle($im,0,0,$width-1,$height-1,$line_color);

// Add title

$title = 'Poll Results';

$title_dimensions = imagettfbbox($title_size, 0, $font, $title);

$title_length = $title_dimensions[2] - $title_dimensions[0];

$title_height = abs($title_dimensions[7] - $title_dimensions[1]);

$title_above_line = abs($title_dimensions[7]);

$title_x = ($width-$title_length)/2; // center it in x

$title_y = ($y - $title_height)/2 + $title_above_line; // center in y gap

imagettftext($im, $title_size, 0, $title_x, $title_y,

$text_color, $font, $title);

// Draw a base line from a little above first bar location

// to a little below last

imageline($im, $x, $y-5, $x, $height-15, $line_color);

In Part 3, you set up the basic image, allocate the colors, and then begin to draw the graph.

You fill in the background for the graph this time using

imagefilledrectangle($im,0,0,$width,$height,$bg_color);

The imagefilledrectangle() function, as you might imagine, draws a filled-in rectangle. The first parameter is, as usual, the image identifier. Then you must pass it the x and y coordinates of the start point and the end point of the rectangle. These points correspond to the upper-left corner and lower-right corner, respectively. In this case, you fill the entire canvas with the background color, which is the last parameter, and it’s white.

You then call

imagerectangle($im,0,0,$width-1,$height-1,$line_color);

to draw a black outline around the edge of the canvas. This function draws an outlined rectangle instead of a filled one. The parameters are the same. Notice that the rectangle is drawn to $width-1 and $height-1—a canvas of width by height goes from (0, 0) to these values. If you drew it to $width and $height, the rectangle would be outside the canvas area.

You use the same logic and functions as in the preceding script to center and write the title on the graph.

Finally, you draw the baseline for the bars with

imageline($im, $x, $y-5, $x, $height-15, $line_color);

The imageline() function draws a line on the image you specify ($im) from one set of coordinates ($x, $y-5) to another ($x, $height-15), in the color specified by $line_color.

In this case, you draw the baseline from a little above where you want to draw the first bar, to a little above the bottom of the canvas.

You are now ready to fill in the data on the graph. Part 4 is shown in Listing 22.5.4.

Listing 22.5.4 showpoll.php—Part 4 Draws the Actual Data onto the Graph and Finishes Up

/*******************************************

Draw data into graph

*******************************************/

// Get each line of db data and draw corresponding bars

while ($row = $result->fetch_object())

{

if ($total_votes > 0)

$percent = intval(($row->num_votes/$total_votes)*100);

else

$percent = 0;

// display percent for this value

$percent_dimensions = imagettfbbox($main_size, 0, $font, $percent.'%'),

$percent_length = $percent_dimensions[2] - $percent_dimensions[0];

imagettftext($im, $main_size, 0, $width-$percent_length-$text_indent,

$y+($bar_height/2), $percent_color, $font, $percent.'%'),

// length of bar for this value

$bar_length = $x + ($percent * $bar_unit);

// draw bar for this value

imagefilledrectangle($im, $x, $y-2, $bar_length, $y+$bar_height, $bar_color);

// draw title for this value

imagettftext($im, $main_size, 0, $text_indent, $y+($bar_height/2),

$text_color, $font, "$row->candidate");

// draw outline showing 100%

imagerectangle($im, $bar_length+1, $y-2,

($x+(100*$bar_unit)), $y+$bar_height, $line_color);

// display numbers

imagettftext($im, $small_size, 0, $x+(100*$bar_unit)-50, $y+($bar_height/2),

$number_color, $font, $row->num_votes.'/'.$total_votes);

// move down to next bar

$y=$y+($bar_height+$bar_spacing);

}

/*******************************************

Display image

*******************************************/

Header('Content-type: image/png'),

imagepng($im);

/*******************************************

Clean up

*******************************************/

imagedestroy($im);

?>

Part 4 goes through the candidates from the database one by one, works out the percentage of votes, and draws the bars and labels for each candidate.

Again, you add labels using imagettftext() and draw the bars as filled rectangles using imagefilledrectangle():

imagefilledrectangle($im, $x, $y-2, $bar_length, $y+$bar_height, $bar_color);

You add outlines for the 100% mark using imagerectangle():

imagerectangle($im, $bar_length+1, $y-2,

($x+(100*$bar_unit)), $y+$bar_height, $line_color);

After you have drawn all the bars, you again output the image using imagepng() and clean up after yourself using imagedestroy().

This long-ish script can be easily adapted to suit your needs or to autogenerate polls via an interface. One important feature that this script is missing is any sort of anticheating mechanism. Users would quickly discover that they can vote repeatedly and make the result meaningless.

You can use a similar approach to draw line graphs, and even pie charts, if you are good at mathematics.

Using Other Image Functions

In addition to the image functions used in this chapter, many others are available. Drawing with a programming language takes a long time and some trial and error to get right. Always begin by sketching what you want to draw, and then you can hit the manual for any extra functions you might need.

Further Reading

A lot of reading material is available online. If you’re having trouble with the image functions, it sometimes helps to look at the source documentation for GD because the PHP functions are wrappers for this library. The GD documentation is available at http://www.libgd.org/Documentation.

Remember, though, the PHP version of GD2 is a fork of the main library, so some details will vary.

You can also find some excellent tutorials on particular types of graph applications, particularly at Zend and Devshed at http://www.zend.com and http://devshed.com, respectively.

The bar chart application in this chapter was inspired by the dynamic bar graph script written by Steve Maranda, available from Devshed.

Next

In the next chapter, we tackle PHP’s handy session control functionality.