EVERY YEAR at holiday time I agonize whether or not to send a holiday gift to Deidre. She’s been sending me the same box of cheese for 20 years. She lives in California. I live in Wisconsin. I’m surrounded by cheese. The last thing I need is a box of cheese. Often the box of cheese she sends is from a company in Wisconsin, which is ironic. Even more ironic is the fact that I started this chain of gift-giving. Deidre and I started off as business associates and then got to know each other as friends. One year I got caught up in the “spirit of the season” and sent her a holiday present in the mail. Shortly thereafter the first box of cheese showed up. The following year the box of cheese arrived early, and I had to send her a present in return. On and on the gift-giving has continued for 20 years. I sometimes think that I should stop sending a present. Then maybe she wouldn’t send me the cheese, and we could stop this worn-out holiday tradition. But would she think badly of me if one year I didn’t send a gift? And so the tradition continues. Maybe Deidre will read this book and get mad at me and stop the cheese!

WE RETURN FAVORS and exchange gifts. Sometimes we do this out of love or for fun. But many times we give gifts or favors out of a sense of obligation. If I give you a gift or do you a favor, you will feel indebted to me. You will want to give me a gift or do me a favor in return; possibly to be nice, but mainly to get rid of the feeling of indebtedness. This is a largely unconscious feeling, and it is quite strong. This is called reciprocity.

The theory is that this gift-giving and favor-swapping developed in human societies because it is useful in the survival of the species. If one person gives someone something (food, shelter, money, a gift, or favor), that person will trigger the indebtedness. If the person who did the gifting finds him or herself in need of something in the future, he can “call-in” the favor. These “deals” or arrangements encouraged cooperation between individuals in a group, and that cooperation allowed the group to grow and support each other.

Richard Leakey, a paleontologist and son of the famous archeologists Louis and Mary Leakey, wrote “We are human because our ancestors learned to share their food and their skills in an honored network of obligation.” (Leakey and Lewin, 1978)

RECIPROCITY DOESN’T MEAN that if we give others a gift we will automatically get a gift in return. What does happen is that if we give them a gift, we will trigger a feeling of indebtedness—a feeling of indebtedness that they’ll want to get rid of by responding with gifts or favors. Sometimes they will ignore their feelings, but those feelings will linger. It might even take a long time for them to act on the feelings. Another interesting aspect about reciprocity: when they return the gift or favor, that gift or favor may be different in value than the original gift. Usually, they won’t reciprocate with something of lesser value—that would leave them with a feeling of an unpaid debt. Often, they reciprocate with something of higher value than the original gift.

IN A RESEARCH study by Kunz and Wolcott (1976), researchers sent out Christmas cards to random people and received cards back from many of them—all strangers! Like my situation with Deidre, many of these Christmas cards kept arriving year after year.

Imagine that you’ve signed up to participate in a research study on creativity. You go into a room with another participant, whom we’ll call Joe. The two of you are in the room working separately on your creativity tasks. After a while, the experimenter comes in the room to tell you that you’ll have a 10-minute break. Joe asks if he can leave the room during the break, and the experimenter says yes. Joe comes back a few minutes later with two cans of soda. He’s opened one, but he hands the other one to you and says, “I asked the guy if it was okay to bring a soda in here and he said yes, so I brought one for you, too.” You thank him and open the soda. The experimenter comes in the room and starts the art creativity tasks again. Another short while later the experimenter says that he has to first check on something, then you are free to go. While he is gone, Joe says to you, “Hey, would you be interested in buying some raffle tickets? The person who sells the most tickets gets a prize.” You say okay and buy three raffle tickets for $5.

It turns out that Joe is really part of the experiment. The experiment was on reciprocity. If Joe gave you a can of soda, would you then reciprocate and buy the raffle tickets when he asked you? Half of the time, Joe offers a soda. The other half, he doesn’t. The results? When Joe brings you a soda, you’re twice as likely to purchase a raffle ticket than when Joe doesn’t bring you a soda. You feel that you have to buy the raffle tickets because he gave you a gift—even though the raffle tickets cost a lot more than the soda did (Regan, 1971).

The power of reciprocity has been well known to people who manage direct marketing campaigns.

For example, a mailing that solicited donations for a veterans group generated an average response rate of 18 percent. When the mailing campaign included personalized address labels, the donations almost doubled to 35 percent (Cialdini, 2007). And it seems that the principle of reciprocity occurs across most, if not all, cultures (Heinrich et al, 2001).

In a mail appeal for donations, the normal response rate was 18 percent. If, however, the mailing included personalized address labels, the donations almost doubled to 35 percent.

Reciprocity is used to persuade you to perform some action, such as making a purchase, volunteering, or funding a project.

LET’S SAY THAT you are on the local school board and I’m part of a group of parents that would like to get new playground equipment. We’ve heard that there are some extra funds left over this year in the school budget. The parent group has selected me to approach the school board and ask for $5,000 of the fund balance for the playground equipment project.

At the meeting in which I’m making my request, I shock the rest of the parent group by asking for $7,500, not $5,000. You and the rest of the school board shake your heads and say, “No, no, we can’t possibly spend that much money for playground equipment.” I look disappointed and then say, “Oh, well, we do have a reduced plan for $5,000.” You ask to see the reduced plan, and I walk out of the meeting with the $5,000 project approved.

What just happened is called concession. When you said no to me, and I accepted that no, my no acted as a gift to you. As a result, you were indebted to me. You had to reciprocate with something. So when I offered the reduced plan for $5,000, you said yes as a way to relieve the indebtedness.

This tactic is sometimes called “rejection then retreat.” The initiator asks a favor that is well above what most people would agree to. After the refusal, the initiator then asks for another favor that is more reasonable and received exactly what he or she wanted in the first place.

WHAT IF I stopped you on the street one day and asked you to chaperone a group of troubled youth on a one-day trip to the zoo? Cialdini et.al. (1975) did just that. If you were like most people in his study, you said no. Only 17 percent of people said yes.

If he first asked people to spend two hours a week as a counselor for the youth for a minimum of two years (a larger request), every one of them declined—100 percent refusal. If he then asked them to chaperone a group of troubled youth on a one-day trip to the zoo, 50 percent agreed. That is nearly three times the number of those who agreed when they were only asked to chaperone. That’s concession working.

That’s how many people agreed to chaperone. But how many actually showed up? Eighty-five percent of the people in the concession group actually showed up, compared with only 50 percent of the group that did not go through the concession process.

A similar study by the same group also found that the concession technique resulted in a higher likelihood that people would volunteer again (84 percent vs. 43 percent). Concession resulted in a greater number of those willing to commit.

For concession to have an effect, the first offer has to be beyond what people will normally agree to, but still has to be considered reasonable. If the first offer is totally outlandish, the retreat (second) request won’t work. In addition, the retreat offer has to be seen as “fair.”

ANYTIME SOMETHING IS given away at a Web site, it has created an opportunity to build indebtedness and reciprocity. This is perhaps a little more complex and subtle than it seems.

Let’s say there is an e-commerce site offering free shipping on orders over $75. Is this reciprocity?

Consider the fact that we not only have to buy something, we have to spend a certain amount of money—perhaps more than we were willing to spend. By agreeing to spend more than we’d originally planned, we presented the first gift (our willingness to spend more money). The company then reciprocates by giving us free shipping. This feels like an even exchange, at best—as such, the offer for free shipping will not create a feeling of indebtedness in us.

For us to consider free shipping to be the gift, we have to feel as if the offer has no strings attached. At Zappos.com’s online shoe store, they offer free shipping with no strings attached. Even better, they offer free shipping if you decide to return the shoes. Now that’s special, which makes the offer feel like a gift to us when we shop their online store.

Zappos.com has free shipping, no strings attached AND free shipping if you want to return what you bought.

Free gifts are very powerful. If a site gives us free gifts, no strings attached—that will trigger reciprocity.

Several years ago, Lands End (a clothing company in the United States) sent me a small Christmas tree ornament with a card. The card read, “Just to say thanks for being our customer.” No coupons, nothing else, just a little ornament and the card. That small gesture 15 years ago continues to influence my behavior today. Every time I need to buy an article of clothing that I could buy from LL Bean, or Eddie Bauer, or any number of places, I always stop and think, “I should see if Lands End has what I am looking for first.”

So, giving a gift away at a Web site that has no strings attached could procure a customer or friend for a long time.

ONE WAY THAT Web sites give gifts is by giving the gift of useful information. For example, if an e-commerce site sells cameras, there could be a portion of the site that features an excellent guide to taking pictures. If users come to the site to read about taking pictures, and they appreciate the information that is provided for free, they might feel as if they’ve been given a gift. This doesn’t guarantee that they’ll buy a camera from the site, but it greatly increases the chances that they will—and that might just keep them from visiting your competitor’s site. Even if they do not purchase right away, they are likely to eventually come back to buy. And this type of information giving works well in getting people to give information, such as filling in a form of data.

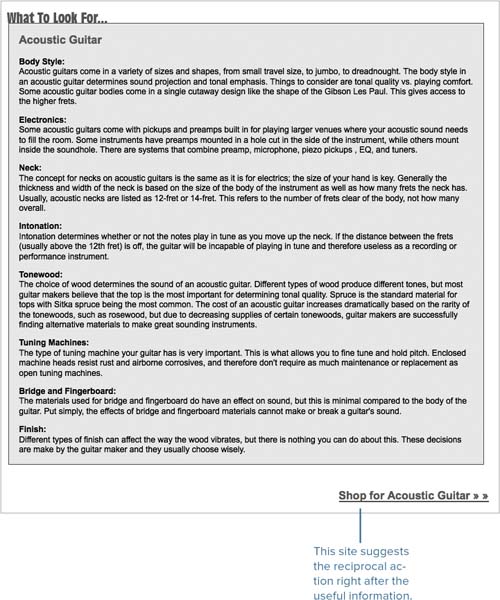

NO STRINGS ATTACHED is powerful, but it is also okay to ask for a reciprocal action—especially when you provide useful information.

Even giving visitors recommendations can be seen as a gift (as long as the recommendations are deemed to be useful information to visitors). If visitors love books on rare antiques and they receive notification that a new book on rare antiques has been published, they’re likely to consider that notice useful information (and a gift of sorts).

Showing your visitors other products they might be interested in buying might be seen by them as a gift from you.

Here’s an idea that is different, but might also trigger reciprocity: A for-profit company can give a donation to a non-profit organization for you, and thereby engender a feeling of indebtedness by you. It’s as though they gave a gift “for you,” even if they gave it to someone else. Now you feel that you should give something to them since they donated for you.

Sites donating for you are giving you a gift of sorts.

The above image shows an example of this concept. If you take a picture of yourself kissing someone and upload it, the site owners, in turn, will donate to an organization of your choice. This act of goodwill is likely to create a feeling of indebtedness in you because the company has not only acted on your behalf, but they’ve likely triggered your emotional connection to your favorite organization.

Now you will feel indebted to them (which is what they want). You will want to return the favor or gift, perhaps by being a loyal customer or by visiting their site again.

In some cases, your gift might be your user information—the Name and Phone fields you see in this example. Sites are known to sell or trade this information with other sites that are looking to expand their audience.