HAVE YOU EVER attended a church or religious service that was not one that you were used to? It might have gone something like this. You weren’t sure what was going to happen next. People were responding or praying or singing or chanting in what seemed like a foreign language. They seemed to be sitting, or standing, or kneeling at various cues. You surreptitiously stole glances at everyone around you and tried to imitate what they were doing. If everyone stood up and put a paper bag on their heads and turned around three times, you probably would have looked to see where your paper bag was.

Why is the behavior of others so compelling? Why do we pay attention to and copy what others do? It’s called social validation.

Most people view themselves as independent thinkers, meaning that they like to think they are unique individuals. The truth is, however, that the need to fit in and belong is wired into our brains and our biology. We want to fit in. We want to be like the crowd. This is such a strong drive, that when people are in a social situation, they will look to others to see how to behave. It’s not a conscious process; we don’t know we’re doing it.

ONE NIGHT IN 1964 a young woman by the name of Kitty Genovese was attacked in Queens, NY and stabbed to death. According to an article in The New York Times, she was stabbed multiple times by the same man over a 30-minute period, screamed for help repeatedly during the attacks, and yet no one went to her aid. The article said that 38 people witnessed the attack, but no one intervened to help.

The New York Times article started a storm of speculation by social scientists about why normal, upstanding citizens would let something like that happen. Why did no one go to Kitty’s aid? Is it because people are apathetic? Are they afraid that if they intervene they’ll be killed too? A line of research into what is called the bystander effect was started.

Latane and Darley (1970) conducted a series of studies culminating in a book in 1970 called The Unresponsive Bystander: Why Doesn’t He Help?

In one of Latane and Darley’s studies, they would have someone act as though they were having an epileptic seizure on a city street. Would someone coming upon the person in distress stop and help? They studied varying numbers of onlookers. If a single bystander came upon the person in distress, that individual helped 85 percent of the time. If five people were present, they found that one person stepped forward to help only 31 percent of the time. This research supported the notion that if there were others around in a particular situation, most individuals seemed to look to everyone else in the group to determine how they should behave. Most of the time, no one took action. They essentially stood around and looked for somebody else to act.

In another Latane and Darley study (1968), participants sat in a room and completed questionnaires. While they completed their paperwork, smoke was released into the room from a vent. The experimental conditions varied:

• In one experimental condition, there was only one subject in the room, and that subject was not aware of the study.

• In another, there were three individuals in the room, but two were aware of the experiment. Those two were instructed to act unconcerned and continue to fill out their questionnaires while smoke filled the room.

• In a third experimental condition, there were three subjects in the room, all of whom were entirely unaware of the experiment.

So what did people do? Did anyone take action by leaving the room and reporting the smoke?

In the first condition, 75 percent of the subjects left the room and reported the smoke. In the second condition, only 10 percent of the subjects left the room and reported the smoke. In the third experiment, 38 percent left the room and reported the smoke.

This research supports the notion that we look to others to validate what our behavior should be. The research shows that this is especially true when we’re uncertain about what to do.

People look to others to decide what they should do. This is especially true when they are uncertain about whether or what action to take.

A 1995 New York Times article cast doubt on the first article’s description of the Kitty Genovese incident. The article raised the possibility that the number of people actually witnessing the event was exaggerated. Based on a later analysis of the data and the crime scene, it is likely that some people (but not necessarily 38 people) heard or saw something, and also noted that those individuals might have had difficulty figuring out what was going on. Still, the line of research that was started in the bystander effect is strong, and the data holds.

IN A MORE recent study on the bystander effect (Markey, 2000), Markey asked whether the bystander effect would work in chat groups.

• If you asked a question in a chat group, would your sex determine how long it would take to get an answer?

• Would the number of other people (bystanders) in the chat room affect the time it would take to get help?

• Finally, if you asked for help from a specific person and addressed him by name, would you receive help faster?

The results? Gender didn’t have an effect, but the more people who were present in the chat group, the longer it took for someone to get help. Each additional person added to the chat group added about three seconds to the time it took to get help.

For example, with only two people in the chat room, it took 30 seconds to get a response. With 19 people in the chat room, it took over 65 seconds to get a response. If you addressed a particular person, then it was as though no one else were in the room, and it took only 30 seconds to get a response.

Imagine you’re at a chain superstore looking for an HD flat-screen television. You stand there and stare at the large wall of HD televisions showing NASCAR races. An innocent bystander meanders by and you grab him and say, “What do you think of this TV? Did you buy one? Would you buy it again if you had to do it all over?” He tells you his opinion and walks away. You grab the next person you see and say, “Hey there, do you have this TV? What do you think of it?” She tells you her opinion and walks away. You are at the store for 13 hours gathering opinions. This goes on until you feel secure in a decision.

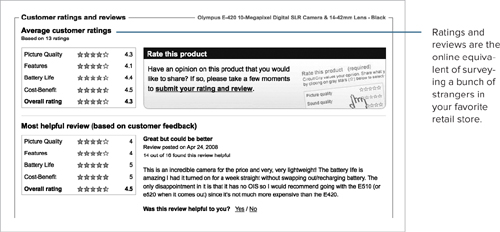

Sound absurd? In the “real world,” it is absurd. Online, it’s not so absurd. However, you won’t need 13 hours to browse products on a Web site. The online version of consumer feedback is faster. You can gather data by reading ratings and reviews. We will avidly read reviews from total strangers, and these reviews will sway our decision on whether, what, and when to buy. Why? We don’t know who the people reviewing the product are, where they come from, their likes and dislikes, or if they are anything like us—and yet, we trust them. If we see that a product has received only one out of five stars, we don’t even take a closer look. It’s social validation at work.

How does social validation affect how we use Web sites? Online ratings and reviews influence us greatly—most powerfully at a non-conscious level.

There are lots of ways to use ratings. Some are more effective than others.

For example, the site that follows doesn’t put any rating information on the first page. We have to click on a specific product before the rating appears. This means they aren’t using social validation as effectively as they could.

By waiting until a later screen to show rating information, they risk losing our attention. We may never get to the next screen to even see the ratings.

Once they show ratings, they do a great job. Notice they even have ratings on different criteria, such as comfort and look. They also show the number of reviewers. The more reviewers there are, the more powerful the impact of social validation will be.

And, finally, the actual reviews themselves.

There is one way the conscious mind might kick in to the conversation. Sometimes (but it’s rare), we start to get suspicious. This usually happens only if we have information that leads us to doubt ratings. For example, a friend of mine used to work at a company that hired people to post positive product ratings. “What if they’re all fake?” she asked.

Now her cortex (new brain) is disagreeing with her old brain. Her old brain says, “I want to be like everyone else,” even when she’s not aware it’s saying that. But her new brain says, “Maybe this isn’t accurate data.” The old brain will probably win in the end. If she reads some reviews that are not 100 percent positive, and if the people writing those reviews seem like a “real” person who actually used the product, then the new brain’s objections can be squelched fairly easily.

Ratings and reviews work unconsciously to activate our need for social validation. But they also give us the rationalization we need or want after we have made our decision unconsciously. Data, charts, graphs, and statistics allow us to tell ourselves we are making the wise choice.

Statistics and a bar chart appeal to our idea that we are making a logical choice, even though our choice is based on unconscious processing.

The most powerful ratings and reviews involve narratives and storytelling. See Chapter 10 for more information about the power of stories.

At this next site, they provide information about the person who wrote the review, as well as a summary of that individual’s experience with the product. They have sketched out a mini “persona” and “scenario.” This adds to the narrative element, making the review even more powerful.

Ideally, the information provided about reviewers is more detailed than the name and location you see here. You’ll learn more about that later in this chapter.

Customer feedback is not limited to the product itself. Reviewers can post comments regarding the company.

Reviews of the company as a whole are effective too.

Reviewer feedback is most powerful when we know more about the reviewers than just their names and the dates their feedback was posted.

We listen more closely to people we know and trust. If we are listening to someone we don’t know, then we will try to (unconsciously) determine if the person is like us (for more information about this concept, see Chapter 8). We are also very influenced by stories, which you’ll learn more about in Chapter 10.

Taking this into account, what kinds of ratings and reviews will influence us the most? We’re most influenced (in this order) when:

![]() We are most influenced when we know the person and the person is telling a story. It is unlikely that we will be reading a review online by someone we actually know. That brings us then to #2.

We are most influenced when we know the person and the person is telling a story. It is unlikely that we will be reading a review online by someone we actually know. That brings us then to #2.

![]() We are somewhat less influenced when we don’t necessarily know the person, but it’s still someone we can imagine because there is a persona, a name (or company name). Again, it always helps if the person is telling a story.

We are somewhat less influenced when we don’t necessarily know the person, but it’s still someone we can imagine because there is a persona, a name (or company name). Again, it always helps if the person is telling a story.

![]() We’re even less influenced when we don’t know the person, and we can’t imagine them, but we are provided with a story.

We’re even less influenced when we don’t know the person, and we can’t imagine them, but we are provided with a story.

![]() We are least influenced when we don’t know the person, and we’re provided with only a rating.

We are least influenced when we don’t know the person, and we’re provided with only a rating.

In the example that follows, we’re at least provided with the full name of the person and her company.

Social validation not only influences our purchase decisions, but it also affects other behavior, such as how we might experience a Web site. For example, a highly-rated video might influence us to watch the video ourselves, thereby influencing our behavior. Here are ratings on videos to watch at YouTube.

Showing how many people performed a particular action at the Web site is powerful. This example shows how many people watched a particular video.

And here’s an interesting twist: What are others doing right now at the same Web site?

Even better, show me what people are doing RIGHT NOW.