Chapter 5

Understanding the Essentials of VBA Syntax

In this chapter, you'll learn the essentials of VBA syntax, building on what you learned via practical examples from the previous chapters. This chapter defines the key terms that you need to know about VBA to get going with it, and you'll also practice using some of the features in the Visual Basic Editor.

You'll find lots of definitions of programming terms as you work your way through this chapter. If you come across something that doesn't yet make sense to you, just keep going. You'll most likely find an explanation in the next few pages. And also remember that few people can recall all the programming punctuation or commands that they need for a macro. Google is your friend in such cases.

Getting Ready

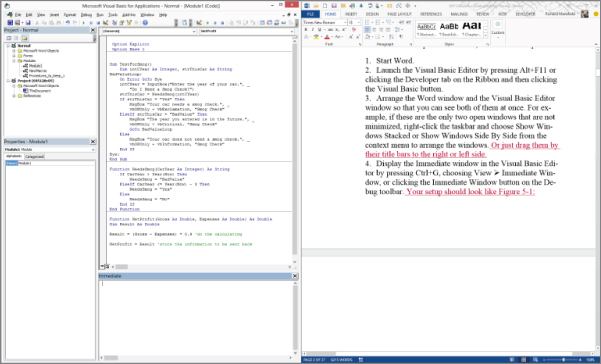

To learn most efficiently in this next section, arrange the Visual Basic Editor in Word by performing the following steps. This chapter focuses on Word because it's the most widely used of the VBA-enabled applications. If you prefer not to use Word, read along anyway without performing the actions on the computer. These examples are easy to follow. (Much of this code will work on any VBA host application, though many of the commands shown here are specific to Word.) Here are the steps:

- Start Word.

- Launch the Visual Basic Editor by clicking Developer ➢ Visual Basic.

- Arrange the Word window and the Visual Basic Editor window so that you can see both of them at once.

For example, if these are the only two open windows that are not minimized, right-click the Taskbar and choose Show Windows Stacked or Show Windows Side By Side from the context menu to arrange the windows, or just drag them by their title bars to the right or left side. In Windows 10 you can press Windows Key+← or Windows Key+→.

- Display the Immediate window in the Visual Basic Editor by pressing Ctrl+G, choosing View ➢ Immediate Window, or clicking the Immediate Window button on the Debug toolbar.

Your setup should basically look like Figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1 The Visual Basic Editor set up alongside a Word document. This is a good way to edit or debug macros. You can see where you are in the code and, often, the effect the macro is having.

Procedures

A procedure in VBA is a named unit of code that contains a sequence of statements to be executed as a group. You can write your own procedures (Subs or functions), but VBA itself has a library of prewritten procedures you can use as well.

For example, VBA contains a function (a type of procedure) named Left, which returns the left portion of a text string that you specify. For example, hello is a string of text five characters long. The statement Left("hello", 3) returns the leftmost three characters of the string: hel. (You could then go on to display this three-character string in a message box or use it in code.) The name assigned to the procedure gives you a way to refer to the procedure in your code.

When you write a macro, you are writing a procedure of your own (as opposed to a procedure like left that's built into VBA already).

Your macros in VBA must be contained in a procedure (between a Sub and an or within a function. If your code isn't thus contained, VBA can't execute it and an error occurs. (The exception is statements you execute in the Immediate window, which take place outside a procedure. However, the contents of the Immediate window exist only during the current VBA editing session and are used for testing code. They cannot be executed from the host application via buttons, ribbons, or keyboard shortcuts. Nor will they be there when you restart the application.)End Sub),

A macro—in other words the code inside Sub to End Sub—is one type of procedure.

A collection of procedures are contained within modules, which in turn are contained within project files, templates, or other VBA host objects, such as user forms.

Just remember that there are two types of procedures: functions and subprocedures (usually called just subs). The VBA macros you create, however, are usually going to be subs.

Functions

A function in VBA is the other kind of VBA procedure. Like a sub, a function is a procedure designed to perform a specific and limited task. For example, the built-in VBA Left function returns the left part of a text string, and the Right function, its counterpart, returns the right part of a text string. Each function has a clear task that you use it for, and it doesn't do anything else. Left just does its one, simple job.

You can create your own function procedures (in addition to the normal macro sub procedures) as well. You'll create your own functions later in the book. They will begin with a Function statement and end with an End Function statement.

What distinguishes a sub from a function is that a sub doesn't return a value and all functions do. A returned value (datum) is whatever results from the function doing its job. For example, built into VBA is a Left function. It returns the left part of a string, such as hel. Other functions return different kinds of results. Some, for example, just test a condition and return True if the condition is met and False if it is not met. But just remember that what distinguishes a function is that it returns some value. Subs don't.

Subprocedures

A sub—subprocedure (also called a subroutine)—like a function, is a complete procedure designed to perform a specific task, but unlike a function, a sub doesn't return a value.

Note that many tasks need not return a result. For example, the Transpose_Word macros you created earlier in this book merely switch a pair of words in a document. There's no need for any value to be returned to VBA for further use. Job done.

On the other hand, if a procedure calculates sales tax, there is a result (the amount of tax that was calculated), so that value must be returned by the procedure for display to the user or for some other use. All the macros you record using the Macro Recorder are subs, as are many of the procedures you'll look at in the rest of this book.

Each sub begins with a Sub statement and ends with an End Sub statement.

Statements

When you create a macro in VBA, you're writing statements, which are similar to sentences in ordinary speech. A statement is a line of code that describes an action, defines an item, or gives the value of a variable. VBA usually has one statement per line of code, although you can put more than one statement on a line by separating them with colons. (This isn't usually a good idea because it makes your code harder to read. Most programmers stick to one statement per line.)

You can also break a lengthy line of code onto a second line or a subsequent line to make it easier to read (although this isn't usually necessary). You continue a statement onto the next line by using a line-continuation character: an underscore (_) preceded by a space (and followed by a carriage return; in other words, press the Enter key). You continue a line strictly for visual convenience on your monitor. VBA still reads a continued line as a single “virtual” line of code. In other words, no matter how many line continuations you use for easy-to-read formatting, during execution it's still a single statement to VBA. Here's an example. Note the underscore that tells VBA to read this as a single, continuous line of code, even though it's broken into two visual lines:

Selection.InsertSymbol Font:="Wingdings", CharacterNumber:=-3880, Unicode _:=True

So, think of VBA code as a series of sentences, each on its own line (or continued), that are usually executed one by one down from the top. Just like a list of steps to take when following a recipe in a cookbook.

VBA statements vary widely in length and complexity. A statement can range in length from a single word (such as Beep, which makes the computer beep) to very long and complicated lines involving many components. But to make it easy to read your code, try to make your lines as brief as possible.

That said, let's examine the makeup of several sample VBA statements in Word. Most of these will use the ActiveDocument object, which represents the currently active (the one that's visible) document in the current session of Word. However, a couple of these statements use the Documents collection, which represents all open documents (including the active document). And one of our example statements uses the Selection object, which represents the current selection within a document (selected text or just the location of the blinking insertion cursor if nothing is selected). Don't worry if some of the following VBA code statements aren't immediately comprehensible—you'll understand them soon enough.

Here are some example statements for you to try:

Documents.Open “c: empSample Document.docm"MsgBox ActiveDocument.NameActiveDocument.Words(1).Text = “Industry"ActiveDocument.Close SaveChanges:=wdDoNotSaveChangesDocuments.AddSelection.TypeText “The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog."Documents.Close SaveChanges:=wdDoNotSaveChangesApplication.Quit

Let's look at each of these statements in turn. The statement

Documents.Open “c: empSample Document.docm"uses the Open method of the Documents collection to open the specified document—in this case, Sample Document.docm. Try it: type this statement in the Immediate window, substituting a path and filename of a document that exists on your computer for empSample Document.

docm.

Press the Enter key, and VBA opens the target document in the Word window. Just as when you open a document by hand while working interactively in Word, this statement in the macro makes this document the active document (the document whose window has the focus; in other words, the window you can see and that will therefore take input from keystrokes or mouse activity).

The statement

MsgBox ActiveDocument.Nameuses the MsgBox function (built into VBA) to display to the user the Name property of the ActiveDocument object (in this example, Sample Document.docm). As an experiment, type this MsgBox statement into the Immediate window (type in lowercase, and use VBA's Help features as you choose) and press the Enter key. VBA displays a message box over the Word window. Click the OK button to dismiss the message box.

Now you see how useful the Immediate window can be when you just want to quickly test a statement to see its effects. You don't have to execute its entire macro. You can just try out a single statement (a single line of code) in the Immediate window if you want to see what it does.

Next, the statement

ActiveDocument.Words(1).Text = “Industry"uses the assignment operator (the equal [=] sign) to assign the value Industry to the Text property of the first item in the Words collection in the ActiveDocument object. Enter this statement in the Immediate window and press the Enter key. You'll see the word Industry displayed in the current typeface at the beginning of the document you opened.

Note that after this line executes, the blinking insertion point appears at the beginning of this word rather than at the end of the word, where it would be if you'd typed the word. This happens because VBA manipulates the properties of the document (in this case the Words collection) directly rather than imitating “typing” into it.

The statement

ActiveDocument.Close SaveChanges:=wdDoNotSaveChangesuses the Close method to close the ActiveDocument object. It uses one argument, SaveChanges, which controls whether Word saves the document that's being closed (if the document contains unsaved changes). In this case, the statement uses the constant wdDoNotSaveChanges to specify that Word shouldn't save changes when closing this document. Enter this statement in the Immediate window and press the Enter key, and you'll see VBA make Word close the document.

An argument is information you send to a procedure. For example, in this next statement the argument is the text string show, which is sent to the built-in VBA MsgBox function:

MsgBox ("show")A MsgBox function will display any text. So you send it an argument: the particular text you want it to display. You'll learn more about arguments shortly.

Now try entering this statement in the Immediate window:

Documents.AddThis statement uses the Add method of the Documents collection to add a new Document object to the Documents collection. In other words, it creates a new document. Because the statement doesn't specify which template to use, the new document is based on the default template (Normal.dotm). When you enter this statement in the Immediate window and press Enter, Word creates a new document. As usual, this new document becomes the active document.

The statement

Selection.TypeText “The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog."uses the TypeText method of the Selection object to type text into the active document at the position of the insertion point or current selection. (The Selection object represents the current selection, which can be either a “collapsed” selection—a mere insertion point with nothing actually selected, as in this example—or one or more selected objects, such as one or more words.)

If text is selected in the active document, that selection is overwritten—unless you've cleared the Typing Replaces Selected Text check box by pressing Alt+F then I, and then clicking the Advanced option in the left pane of the Word Options dialog box. In that case, the selection is collapsed to its beginning and the new text is inserted before the previously selected text.

But in this example—because you just created a new document—nothing is yet selected. Enter the previous Selection.TypeText statement in the Immediate window and press the Enter key, and Word enters the text. Note that this time the insertion point ends up after the inserted text; the TypeText method of the Selection object is analogous to typing something into Word yourself.

The statement

Documents.Close SaveChanges:=wdDoNotSaveChangesis similar to an ActiveDocument.Close SaveChanges:=wdDoNotSaveChanges statement except that it works on the Documents collection rather than the ActiveDocument object. The Documents collection represents all open documents in the current Word session. So this statement closes all open documents and doesn't save any unsaved changes in them. Enter this statement in the Immediate window and press Enter, and you'll see that Word closes all the open documents.

The statement

Application.Quituses the Quit method of the Application object to close the Word application. Enter the statement in the Immediate window and press the Enter key. Word closes itself, also closing the Visual Basic Editor in the process because Word is the host for the Visual Basic Editor.

Keywords

A keyword is a word that is part of the built-in VBA language. It's part of VBA diction. I like to call keywords commands. Here are some examples:

- The

Subkeyword indicates the beginning of a sub, and theEnd Subkeywords mark the end of a sub. - The

Functionkeyword indicates the beginning of a function, and theEnd Functionkeywords mark the end of a function. - The

Dimkeyword starts a declaration (for example, of a variable) and theAskeyword links the item declared to its type, which is also a keyword. For example, in the statementDim strExample As String, there are three keywords:Dim,As, andString.

The names of functions and subs are not keywords (neither the built-in procedures nor procedures you write).

Expressions

An expression involves multiple commands, working together as a unit. An expression consists of a combination of keywords, operators, variables, and/or constants that, when executed, results in (or resolves to) a string, number, or object.

For example, you could use an expression to do a math calculation or to compare one variable against another. Here's an example of a numeric expression (it's shown in boldface) that compares the variable N to the number 4 by using the > (greater than) operator:

If N > 4 ThenThe result of this expression will depend on whatever value is currently held in the variable N. If it holds 12, then the expression will result in TRUE because 12 is greater than 4. More on expressions later.

Operators

An operator is a symbol you use to specify a relationship between the values in an expression—to compare, combine, or otherwise manipulate the values in an expression. VBA has four kinds of operators:

- Arithmetic operators (such as

+and–) perform mathematical calculations. - Comparison operators (such as

<and>, less than and greater than, respectively) compare values. - Logical operators (such as

And,Not, andOr) build logical structures. - The concatenation operator (

&) joins two strings together.

You'll look at the different kinds of operators and how they work in Chapter 11, “Making Decisions in Your Code.”

Variables

Variables are very important in programming. A variable is a location in memory set aside for storing a piece of information—information that can change while a procedure is running. (Think of it as a named, resizable compartment within the memory area, like a small file folder. This isn't precisely how the computer actually handles variables, but it's how the process appears to work to us programmers.)

For example, if you need users to input their name via an input box, you'll typically store the name in a variable so you can work with it further down in some later statement in the macro.

Or perhaps you want to get a total of several numbers that the user types in. You would have a variable that holds the current sum total—which keeps changing (varying) as the user types in more numbers.

VBA uses several types of variables, including these:

- Strings store a text character or a group of characters.

- Integers store whole numbers (numbers without fractions).

- Objects store objects.

- Variants can store any type of data. Variant is the default type of variable.

Either you can let VBA create Variant variables as the default type, or you can specify another data type if you wish. Specifying the types of variables has certain advantages that you'll learn about in due course.

For the moment, try creating a variable in the Immediate window. Type the following line and press Enter:

myVariable = “Some sample text"Nothing visible happens, but VBA has created the myVariable variable. It has set aside some memory and labeled that area myVariable. It also stored the text string Some sample text in that variable's memory location. Now, type the following line into the Immediate window and press Enter:

MsgBox myVariableThis time, you can see the result: VBA goes to the memory area you specified (that was labeled with the variable name myVariable) and retrieves the value, the string. A message box appears containing the text you had stored in the variable.

You can declare variables either explicitly or implicitly. An explicit declaration is a line of code that specifies the name you want to give the variable, and usually its type, before you use the variable in your code. Here's an explicit variable declaration:

Dim myVariable As StringAn implicit declaration means that you don't bother with that explicit declaration statement. Instead, you just use the variable name in some other statement. VBA then stores the data in a Variant variable type because you didn't specify the type.

In other words, if you just use a variable in your code without declaring it, it's implicit.

Here's an example of implicit declaration:

myVariable = “Some sample text"You never explicitly declared this variable using Dim. This is the first time that myVariable appeared in your code. All you did was to just assign some data (the text string) to it. So VBA assumes that you want to create the variable implicitly.

In the next few chapters, you'll use a few implicit variable declarations to keep things simple. In other words, you won't have to type in lines of code to declare implicit variables. VBA will create them for you when you first use them in an assignment or other statement.

However, many educators and professional programmers insist on explicit declaration, so we'll do that for the most part in the later sections of this book. Explicit variable declarations make your code easier to understand. What's more beneficial, some types of errors can be avoided if you explicitly declare all your variables to be of a particular type. So declaring is a good habit to get into. And when you or VBA include this line at the top of your code window, you must declare all variables:

Option Explicit

Constants

A constant is similar to a variable. It's a named item that keeps a constant value while a program is executing. The constant's meaning doesn't change during the macro's execution, or indeed ever. (So in this way, it's unlike a variable.) Some programmers use more constants than others—I rarely use user-defined constants. Variables are just fine for holding most data, even data that doesn't vary.

VBA uses two types of constants: intrinsic constants, which are built into the VBA language itself (and individual Office applications' implementations of VBA), and user-defined constants, which you can create. For example, the built-in constant vbOKCancel is always available in VBA to be used with the MsgBox function. This constant creates a message box that contains an OK and a Cancel button. There are sets of built-in constants for colors, printing (vbTab, for example), and other properties. I do use intrinsic constants. They're convenient. And make code more readable.

Concerning constants that you define, you might want to create one to store a piece of information that doesn't change, such as the name of a procedure or the distance between Boston and New York.

In practice, the built-in intrinsic constants are used quite often in VBA programming; user-defined constants not so much. I repeat: It's just as easy to put the distance between those cities in a variable, even though it won't vary.

Arguments

An argument is a piece of information—supplied by a constant, a variable, a literal, or an expression—that you pass to a procedure (a function or sub), or a method. Some arguments are required; others are optional. The text hello there in this MsgBox function is an argument:

MsgBox ("hello there")Arguments often must be enclosed in parentheses, but not always. Here's another example. As you saw earlier, the following statement uses the optional argument SaveChanges to specify whether Word should save any unsaved changes while closing the active document:

ActiveDocument.Close SaveChanges:=wdDoNotSaveChangesThis optional argument uses the built-in constant wdDoNotSaveChanges. It's optional because there are other ways to save.

The Visual Basic Editor's helpful prompts and the Visual Basic Help file show the list of arguments for a function, a sub, or a method in parentheses, with any optional arguments enclosed in brackets. If you have its Auto Quick Info feature activated, the Editor displays the argument list for a function, sub, or method after you type its name followed by a space.

Figure 5.2 shows the argument list for the Document object's Open method. Type Documents.Open, then press the spacebar to see the argument list.

Figure 5.2 Optional arguments are enclosed within brackets.

The FileName argument is required, so it isn't surrounded by brackets. All the other arguments (ConfirmConversions, ReadOnly, AddToRecentFiles, and so on) are optional and therefore are surrounded by brackets.

If you don't supply a value for an optional argument, VBA uses the default value for the argument. (To find out the default value for an argument, consult the VBA Help file. The default is usually the most commonly employed value in most macros.) The Visual Basic Editor uses boldface to indicate the current argument in the list; as you enter each argument, the next argument in the list becomes bold.

Specifying Argument Names vs. Omitting Argument Names

You can add arguments in either of two ways:

- Enter the name of the argument (for example,

ConfirmConversions), followed by a colon, an equal sign (ConfirmConversions:=), and the constant or value you want to set for it (ConfirmConversions:=True). For example, the start of the statement might look like this:Documents.Open FileName:="c: empExample.docm", _ConfirmConversions:=True, ReadOnly:=False - Or enter the constant or value in the appropriate position in the argument list for the method, without entering the name of the argument. The previous statement would look like this:

Documents.Open “c:TempExample.docm", True, False

When you use the first approach—naming the arguments—you don't need to put them in order because VBA looks at their names to identify them. The following statements are functionally equivalent:

Documents.Open ReadOnly:=False, FileName:= “c: empExample.docm", _ReadOnly:=False, ConfirmConversions:=TrueDocuments.Open FileName:="c: empExample.docm", _ConfirmConversions:=True, ReadOnly:=False

You also don't need to indicate to VBA which optional arguments you're omitting.

By contrast, when you don't employ argument names, you're specifying which argument is which simply by its position in the list. Therefore, the arguments must be in the correct order for VBA to recognize them accurately. If you choose to omit an optional argument but to use another optional argument that follows it, enter a comma (as a placeholder) to denote the omitted argument.

For example, the following statement omits the ConfirmConversions argument and uses a comma to denote that the False value refers to the ReadOnly argument rather than the ConfirmConversions argument:

Documents.Open “c: empExample.docm",, FalseRemember that when you type the comma in the Code or the Immediate window, Auto Quick Info moves the boldface to the next argument in the argument list to indicate that it's next in line for your attention.

When to Include the Parentheses around an Argument List

Most programmers enclose argument lists within parentheses. It makes the code easier to read. However, parentheses can be omitted in some circumstances. When you're assigning the result of a function to a variable or other object, you must enclose the whole argument list in parentheses. For example, to assign to the variable objMyDocument the result of opening the document c: empExample.docm, use the following statement:

objMyDocument = Documents.Open(FileName:="c: empExample.docm", _ConfirmConversions:=True, ReadOnly:=False)

However, when you aren't assigning the result of an operation to a variable or an object, you don't need to use the parentheses around the argument list, even though it's common practice to do so. The following examples illustrate how you can either use or leave out parentheses when not assigning a result to a variable or other object:

MsgBox ("Hi there!")MsgBox “Hi there!"

Objects

To VBA, each application consists of a series of objects. Here are a few examples:

- In Word, a document is an object (the

Documentobject), as is a paragraph (theParagraphobject) and a table (theTableobject). Even a single character is an object (theCharacterobject). - In Excel, a workbook is an object (the

Workbookobject), as are the worksheets (theWorksheetobject) and charts (theChartobject). - In PowerPoint, a presentation is an object (the

Presentationobject), as are its slides (theSlideobject) and the shapes (theShapeobject) they contain.

Most of the actions you can take in VBA involve manipulating objects. For example, as you saw earlier, you can close the active document in Word by using the Close method on the ActiveDocument object:

ActiveDocument.CloseCollections

A collection is an object that contains other objects, the way an umbrella-stand object contains umbrella objects. Collections provide a way to access all their members at the same time. For example, the Documents collection contains all the open documents, each of which is an object. Instead of closing Document objects one by one, you can close all open documents by using the Close method on the Documents collection:

Documents.Close

Likewise, you can use a collection to change the properties of all the members of a collection simultaneously. (Press F5 to execute the code in the Immediate window.)

Here's an example of some code that displays, in the Immediate window of the Editor, all the names of the objects in Word's CommandBars collection:

'fetch the number of commandbarsn = CommandBars.Count'display all their namesFor i = 1 To nDebug.Print CommandBars(i).NameNext i

Properties

Each object has a number of properties. Think of properties as the qualities of an object, such as its color, size, and so on.

For example, the current document in Word has properties such as the number of sentences in the document. Type this into the Immediate window, then press Enter:

MsgBox (ActiveDocument.Sentences.Count)Here you're using the Count property of the Sentences collection to find out how many sentences are in the document.

Even a single character has various properties, such as its font, font size, and various types of emphasis (bold, italic, strikethrough, and so on).

Methods

A method is something an object can do— a capability. Different objects have different methods, just as different people have different talents. For example, here's a list of some of the methods of the Document object in Word (many of these methods are also available to objects such as the Workbook object in Excel and the Presentation object in PowerPoint):

ActivateActivates the document (the equivalent of selecting the document's window with the keyboard or mouse.)

CloseCloses the document (the equivalent of pressing Alt+F then C, or clicking the Close option after clicking the File tab on the Ribbon.)

SaveSaves the document (the equivalent of pressing Alt+F then S, or clicking the Save option after clicking the File tab on the Ribbon.)

SaveAsSaves the document under a specified name (the equivalent of pressing Alt+F then A, or clicking the Save As option after clicking the File tab on the Ribbon.)

Events

When an event occurs, VBA is aware that something happened, usually something that happened to an object. For example, the opening of a file on the hard drive (either by a user or by a macro procedure) typically generates an event. The user clicking a button in the toolbar generates a Click event. Another way to put it is that when you click a button, you trigger that button's Click event, and VBA becomes aware that this has happened.

By writing code for an event, you can cause VBA to respond appropriately when that event occurs. For example, let's say you display a user form (a window). You might put on your form an OK button. Then you write some code in that OK button's Click event. This code might check that all necessary settings were specified by the user when the user clicked the OK button to close the user form and apply the settings.

You might write more code within that button's Click event that responded (perhaps by displaying a message box) if the user had failed to type in some required information. In essence, you can write code in an event to tell VBA what to do if that event is triggered. You don't have to write code for all events in any given macro. Sometimes you'll write code in only one of them. But if you put a button captioned “Display Results” on a user form, you'd better at least write some code in that button's Click event to display some results, or your users will be baffled when they click this button and nothing happens.

The Bottom Line

- Understand the basics of VBA. VBA includes two types of procedures, used for different purposes.

- Master It Name the two types of procedures used in VBA (and indeed in most computer languages), and describe the difference between them.

- Work with subs and functions. A procedure (a sub or function) is a container for a set of programming statements that accomplish a particular job.

- Master It Write a sub in the Visual Basic Editor that displays a message to the user. Then execute that sub to test it.

- Use the Immediate window to execute individual statements. When you're writing code, you often want to test a single line (a statement) to see if you have the syntax and punctuation right or if it produces the expected result.

- Master It Open the Immediate window, type in a line of code, and then execute that line.

- Understand objects, properties, methods, and events. Object-oriented programming (OOP) means working with objects in your programming. OOP has become the fundamental paradigm upon which large programming projects are built. Generally speaking, macros are not large and therefore they usually don't profit from the clerical and security benefits that OOP offers—these features largely benefit people who write sizable applications, and work as a team.

However, in your programming, you'll make frequent use of code libraries. All VB's commands are part of these libraries, such as the vast VBA set of objects and their members (not to mention the even vaster .NET libraries that tap into the power of the operating system itself). These libraries are huge. So, there needs to be a clerical way to organize the objects and functions within the libraries—to categorize the objects and commands, and allow you to execute the methods and manage their properties and arguments in your own macros. As a result, the most useful aspect of OOP to us VBA macro programmers—taxonomy—is quite valuable even when writing brief macros. It's a way to quickly locate the members you're interested in.

- Master It Look up the

Documentobject in the Visual Basic Editor's Help system; then look at its methods.

- Master It Look up the