11

Offering Depiction

VARYING THE VARIABLES

Leonardo da Vinci, Picasso, Frank Lloyd Wright, and, to bring up a current-day business example, IDEO, all discovered new possibilities more as artists and designers than as explorers. Whereas explorers of terrae incognitae past used maps to guide their ventures, artists and designers guide their creative process via various forms of expression, including frameworks, methods, rules, and principles. These push them along the path to generating new creative solutions, whether purely artistic, primarily pragmatic, or somewhere in between. Artists often employ the golden ratio. Engineers turn their knowledge of loads, materials, and physics into design theory, guidelines, and rules. Architects follow principles of design to produce both the form and function of their creations. And now designers of experiences have one more valuable tool to add to their repertoire: the Experience Design Canvas, to be employed in conjunction with the Varying the Variables expedition introduced here in this chapter.

The Experience Design Canvas

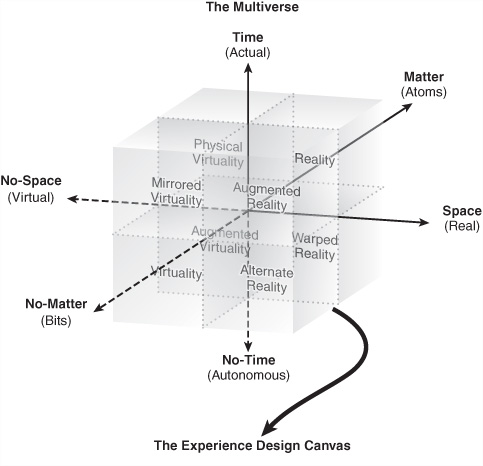

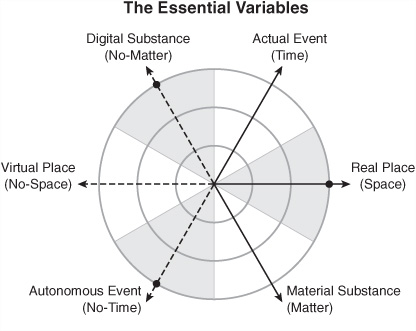

This new tool focuses squarely on the second number of the 8-6-3-1 architecture at the heart of the Multiverse: the six variables. It is here in this chapter where we take full advantage of these independent variables of experience design, as illustrated in Figure 11.1. Through this focus the Experience Design Canvas serves as a platform not only for engendering ideas and discovering opportunities but for designing experiences as well. With the Varying the Variables expedition you do not act as an explorer so much as a designer, depicting experiences (existing or imagined) on the Design Canvas. You select experiential elements from the full palette of variables to depict and design how digital and material substances are constructed, how real and virtual places are formed with those substances, and how autonomous and actual events are enacted in those places.

Figure 11.1 The experience design canvas

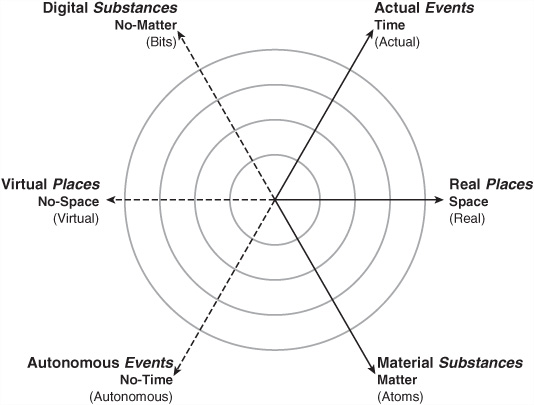

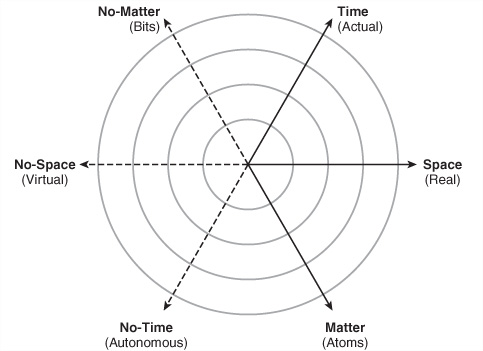

The Canvas simply takes the six variables of the Multiverse and lays them out in a two-dimensional circle, a process illustrated in Figure 11.2, so you easily can plot the intensity of the six variables within the experiences they together create. Rather than losing fidelity as our view shifts from three to two dimensions, this new perspective deepens understanding and reveals opportunities. In Chapter 1, “Cosmos Incogniti,” we described the Multiverse as a sense-making guide for exploring the cosmos incogniti that lie beyond the digital frontier. The Experience Design Canvas lets us more fully explore these worlds, shifting them from unknown to a bit more known, by plotting the variables of possibilities to depict them in a way that lets us see the landscape of what’s around us.

Figure 11.2 From realms to variables

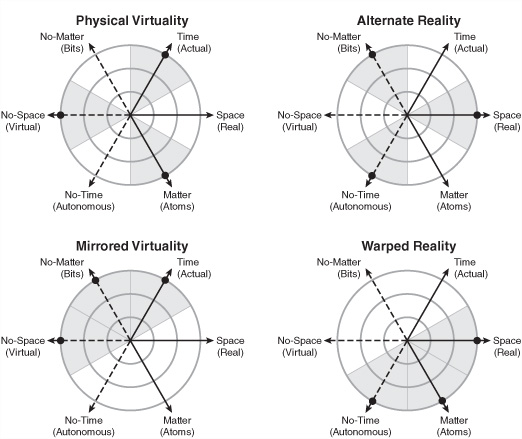

Figure 11.3 then shows each realm of the Multiverse plotted on its respective Canvas, illustrating not only how the 3D to 2D translation works but also revealing the unity of the Multiverse, the Experience Design Canvas, and the 8-6-3-1 architecture. Note the balance and harmony of these realm depictions, with each one positioned across from its polar opposite, forming a progression of patterns between the Realms of the Real on the right side (the same side on which the Space axis resides in the Multiverse framework) and the Realms of the Virtual on the left (where the No-Space axis resides in the Multiverse). The gray areas represent the variables used to create each realm, each one a “pie slice” starting at the middle point, or origin, and extending out to the endmost circle of the Canvas. So Reality, for example, encompasses the three pie slices centered on the lines representing the three variables of Time, Space, and Matter, and Physical Virtuality encompasses the three slices centered on Time, No-Space, and Matter. Of course, the latter realm, along with its opposite, Alternate Reality, looks very different than the others, but this simply results from representing three dimensions onto two; if we were to change the somewhat arbitrary order of the variables—say, Time, Matter, Space instead of Time, Space, Matter—then different realms would have this “split” effect.

Both the Multiverse and its corresponding cousin the Experience Design Canvas serve as ideation tools for discovering new value-creation opportunities. In the case of the eight realms of the Multiverse, the descriptive identifiers such as Alternate Reality or Augmented Virtuality spur idea generation more than if we had identified each of them by their less colorful defining variables (i.e., [No-Time – Space – No-Matter] or [No-Time – No-Space – Matter], respectively). The realm names give aid to understanding, creating eight distinct mental models with easily thought-of exemplars that directionally guide ideation. The Experience Design Canvas foregoes these labels, for once they serve their purpose they only limit thinking to the preexisting mental models, and we don’t want to preclude new-to-the-cosmos ideas that do not fit what we currently mean by each label.

This opens us up vast new areas to be explored and exploited. For the conceptual simplifications provided by the realms of the Multiverse limit our thinking to only three variables at a time, those that comprise each realm. Actual experiences can, and more often than not do, extend beyond the strict confines of any one realm, often encompassing elements that have meaning in four, five, or even all six variables. The Experience Design Canvas lets us depict offerings to reflect the involvement of any or all of these variables—enabling us to take a more sophisticated view of value creation beyond the realms themselves by thinking outside the cube.

Figure 11.3 The eight Realms of the Multiverse

So here we focus on a different set of labels, with different mental models, by using the more descriptive names for the six variables we introduced in Chapter 1, “Cosmos Incogniti”: actual events and autonomous events, real places and virtual places, and material substances and digital substances.

A Variable Design Expedition

Both the Reaching through the Realms expedition, discussed in Chapter 10, “Multiverse Excursion,” and Varying the Variables, covered in this chapter, directly harness the power of the Multiverse to guide discovery, but they do so in distinctly different ways. Reaching through the Realms focuses on methodically walking through the Multiverse realm by realm to see what possibilities each one might reveal. Varying the Variables, on the other hand, ignores the realms completely. Instead, it directs your attention to these six variables in order to consider the possibilities of varying their intensities and configurations.

As with the Reaching expedition, we suggest you conduct this as a group exercise with multiple small teams initially working independently before bringing their ideas together for further discussion, refinement, and selection with the overall group. Being more free-form, however, this expedition does not have the same step-by-step approach. Rather, you initiate a Varying the Variables expedition from a variety of ways: by depicting a familiar offering (whether yours or a competitor’s), by mapping the variables of an idea generated from your previous ideation exercises, or even by doodling, fiddling, and generally messing around with the variables. You can even start with a blank canvas to try to discover new possibilities.

Once you plot an offering on the canvas, whether an existing one or a new idea, look at the overall pattern of variables. Consider the variables’ characteristics, configuration, coherence, complementarity, contrast, and consequence. What characteristics does each variable contribute to the offering? What makes this particular configuration work? Can you see any lack of coherence between the variables involved? Which variables clearly complement one another? Does the contrast between variables enrich or detract from the experience? What consequences result from this particular pattern of variables?

Having now depicted an offering, each team looks for opportunities to create greater value by adjusting the intensity and configuration of variables. If two variables are in conflict, how might the impact of one or the other be reduced? How might one or more variables be doubled or tripled in intensity—perhaps even by an order of magnitude—to yield greater impact overall? How do other competing offerings compare to the one in question? What does this tell you about the value created or, alternatively, how customers sacrifice by not getting exactly what they want?

As you may have gathered, depicting existing offerings or ideas for new offerings encourages unbounded idea generation. Follow a hunch. Scratch an itch. Take a leap into the unknown. Pursue a notion just to see where it leads. Depicting possibilities on the Design Canvas even suits a “blue sky” approach just fine. You never know what ideas will emerge from explorations unencumbered by existing notions of what the offerings should be and what previously has been demonstrated as possible.

Going Beyond the Realms

Now, in order to better understand experience depiction, let us delve deeper into plotting experiences on the Experience Design Canvas. Start by cleansing from your minds—albeit temporarily—what you have so diligently learned about the eight realms. To that end, understand that while plotting the “pure” Multiverse realms (with their three defining variables) on the Design Canvas shows us the Multiverse–Canvas correspondence of idealized realms, depicting the form of actual experiences on the Canvas lets us see what’s really going on.

Take, for example, an Alternate Reality experience, nominally illustrated on the left side of Figure 11.4 as the distinctive combination of No-Time, Space, and No-Matter. This certainly captures the essential variables of any ARG or other experience within this realm, but in such experiences the opposite variables along each of the Event, Place, and Substance dimensions do in fact come in to play, as seen in the fuller picture on the right half. Actual time figures prominently, as the players in an ARG cannot ignore the actual events enacted in the real space where the game’s events play out. In an urban game, traffic, traffic lights, bus schedules, and so forth, all enter into the pace, cadence, rhythm, and timing of the game’s events, which the puppet masters manipulate to fit their own schedules. Further, material substances (such as jars of honey and phone booths) and virtual places (such as websites and phone calls) enter into the mix, yielding an experience whose center of gravity still lies in the three prototypical Alternate Reality variables, but actually spreads across all six variables of the Multiverse.

Figure 11.4 Alternate Reality on the Experience Design Canvas

Understanding the fuller picture of Alternate Reality as represented on the Canvas should spur ARG (and other such experience) designers to explicitly define and address the intended configuration of its variables—flushing out ideas regarding variable conflicts, variable intensity, varying configurations, enhancements, manifestations, augmentations, infusions, embedding, and even customer sacrifice elimination. Even further, although the diagram on the bottom half of Figure 11.4 accurately describes ARGs as presently produced, designers and puppet masters could use the ARG format for an even fuller experience, spreading it out even further on the Canvas to encompass the other variables of the Multiverse (actual events, virtual places, and material substances) more fully and simultaneously. Or they could do the opposite: seek to minimize all but the primary Alternate Reality variables (autonomous events, real places, and digital substances) to focus on and intensify the experience, getting it down to its essence.

That is exactly the thrust of the Varying the Variables expedition, to spur on ideation while simultaneously building experience design capability. Though still systematic to a degree, Varying the Variables takes on a more free-form/organic quality than does Reaching through the Realms. It forces us to recognize that any given experience may comprise anywhere from three variables up to and including all six of the possible variables in the Multiverse, so we not only take our capability to faithfully represent the variables of an experience up a notch but also do the same for our understanding, insight, and ideation.

This expedition provides the means to consider enhancing any experience, from adding what might be missing, minimizing what does not add value, combining variables in new ways, or boosting particular variables. It also provides the means for designing experiences from scratch, considering the intensity of each variable one at a time and the interplay between the variables. Beyond focusing on one particular experience, portraying two different experiences on one Canvas provides the means to explicitly compare and contrast them to expose differences in the intensity and configuration of variables. This one-to-one experience comparison serves to deepen understanding, reveal opportunities, identify customer value as well as sacrifice, stimulate ideation, and advance design.

Depicting Experiences

Again, any experience can be characterized by the six variables of the Multiverse to reflect or capture its actuality, autonomy, reality, virtuality, materiality, or digitality. Plotting these variables on the Experience Design Canvas—whether one experience per canvas or two or more for comparison’s sake—generates insights and uncovers opportunities that otherwise remain hidden. To understand how, let’s see what depicting some easily understood experiences reveals to us.

Think of a real-world experience such as a casual bicycle ride, unenhanced by digital technology, through, say, New York City’s Central Park. How would you rate the values of each variable in the Multiverse? Let’s take the easy ones first—autonomous events enacted, virtual places formed, and digital substances constructed for this experience are all zero. Nothing digital going on here, folks. That leaves the three variables of Reality–Time with its actual events, Space’s real places, and the material substances of Matter. But are the relative intensities of these three variables equal to one another? Or does the significance of Central Park’s contribution to the experience mean the magnitude of the real places variable should be greater than the other two? As with any experience, you are the ultimate arbiter, but we think it does. (Of course, we’re from Minnesota and do not get to bike in Central Park every day.)

Now consider how you would rate the same variables in an obviously more intense experience in Reality, say, climbing the Matterhorn in Switzerland. Relative to the casual ride in the park, think of how much more expansive is this real place, how much more dependent you are on the material substance of the mountain and your climbing equipment, how much more each and every moment proceeding in this actual event means to your experience as you grapple with the climb. Would each of these variables be ten times as intense? A hundred times? Or perhaps a thousand? Again, we report, you decide.

Now take your analysis of these two experiences and plot them onto the Design Canvas, as we have our opinion in Figure 11.5. You see the six independent yet interrelated variables, three of which are again zero, with the rest dialed up greatly—we’re considering it to be a logarithmic scale, so each circle represents an order of magnitude increase in intensity—to reflect the greater impact of the three variables for the mountain-climbing experience. Just by glancing at the area under the curve, as mathematicians say—although in this case it is multiple adjacent curves—you can see how much more intense we believe the mountain-climbing experience is than riding a bike, with the real places and especially material substances contributing a greater portion of that intensity than the flow of actual time.

Figure 11.5 Two reality experiences

When using the Canvas, the scale of the variable values can be whatever best serves your purpose. A logarithmic scale serves you well when seeking or designing order of magnitude increases in variable intensity, as we’ve done here, whereas a linear scale may better serve your need to compare experiences with variables of similar intensity. Once having depicted an experience variable by variable, you can then start thinking about and varying each of them individually and in their collective configuration to discover and depict just the right experience to meet the needs, hopes, and desires of your customers. As just one quick example: turning the climb into a time trial or race would amp up the Time variable commensurate with the other two.

Thinking in Variables

To build up your experience deciphering and depicting skills, think through each of the three dimensions of the Multiverse. Start with the Event dimension and turn your attention first to events enacted, the when of an experience where change and activity—the timing of its events in Time and/or No-Time—play into your customer’s perceptions. With actual events, action marches unrelentingly forward to bring a temporal reality to the experience. These events happen in real time with a pace, beat, direction, and rhythm that pushes, prompts, or tugs the experience incessantly forward. Autonomous events, on the other hand, take the experience wherever it wants in time—backward, forward, sideways, jumping around, slowing down, speeding up, and so on—where events becomes malleable with a nonlinear temporality. These events may not move synchronously, nor exist in the now of reality, but yet still may overlap with actual events. Along this variable of autonomous events, look for experiences that take your customers off the endless conveyer belt of stacked events flowing in reality’s timeframe to bring them the rewards of autonomous events.

Next, study the Place dimension, the where of an experience formed in Space and/or No-Space. Real places bring real-world familiarity to an experience with an emotional appeal that comes from reality’s social and cultural familiarity, what futurist Jerry Paffendorf refers to as the “gravity of reality.”1 Virtual places, on the other hand, bring the experience designer free exercise of imagination to invent new places within the limits of the technology employed to bring them into virtual being. (Note how James Cameron scripted Avatar more than a decade before he could film the movie as he waited for technology to catch up with his dreams.2)

Finally, consider the Substance dimension, the what of an experience constructed in Matter and/or No-Matter. Material substances—whether natural or man-made objects, devices, materials, plants, or animals—first evoke physical sensations followed by the emotions they trigger. These substances can soothe, support, stimulate, shake, strike, shift, shove, or soar your physical being. In their more forceful renditions, they can bump, burn, blast, and bombard your senses. Digital substances, on the other hand, address the senses in a very different manner, coming to the individual in the form of text, graphics, or imagery enhanced by sounds and occasionally other senses. They evoke a variety of emotions, sans the physical impacts, by tweaking your emotions, tugging at your heart, tickling your funny bone, titillating your fancy, triggering your imagination, transporting you to your peaceful spot, tapping your libido, tempting you to anger, taking you down, terrorizing your very being, or touching you deeply in a multitude of ways and degrees.

Playing on the Experience Design Canvas

With this introduction to the variables of the Multiverse and the Experience Design Canvas, you can now go to work discovering new value for your customers on the digital frontier, specifically by playing with the variables of experience. Start by selecting a current offering and plotting it on the canvas. This should produce a lively discussion right off the bat about the relative value or intensity of each variable and the inevitable comparison of the experience in question with other experiences. You could of course even bring customers into this discussion, or ethnographically observe them using an existing or prototyped offering. Once you have produced the six-variable representation of the experience, start playing with its variables to see what ideas emerge. Look for alternative types of value being created, intensified or reduced emotions, or the achievement of a new level of human capability.

As you play with the variables and their overall configuration, think of what each one lends to an experience and how it affects the customer value of that experience. The Variables of Experience box, with its characterization of each variable, can help get you started. As you practice your own Multiverse-enabled experience design, add to these descriptions as you discover more of what each variable contributes to the types of experiences you develop. As you do this, you should find your ideation capability grows—spurred on with your new insights—to flush out ever-greater possibilities to create new economic value.

For example, play with the variables to see what happens when you intensify the digital substances of a previously reality-centered experience. What changes? What value might be added, what value might be taken away? And how does the overall value of the Substance dimension change? Consider a wide variety of variable intensities and mixes, as well as overall experiential forms. Consider the forms of the experience over time; you could even plot each segment in time with its own unique Canvas. Does this give you any ideas about where the current form can be enhanced to add value? Maybe previous forms of the offering lost one form of value in exchange for another. Maybe technology steered it one way for a time and now new technology stands ready to take it in another direction.

Get a little crazy. Stretch your imagination by considering what happens if you could double the order of magnitude of one variable. What might an offering look like that was one—no, make it two orders of magnitude greater? What would the value be to your customers? What technology exists, or is emerging, that would enable this? Now consider more than one variable at a time. Is it possible to create an experience where every variable is relatively equal? What might it look like? What customer value would it have? What might the experience be if all six variables doubled in intensity at once? Can you stage the exact opposite experience by flipping the intensity of every variable to its opposing intensity? What customer value might that have? What does this reveal about the original experience? If you take the Reality experience of driving a NASCAR race car and flip the variables, you end up with iRacing.com, a Virtuality racing experience safe for novices but also real enough to train professional drivers. Do the same with football and you get the Madden NFL video games from EA Sports, where you too can take to the gridiron without a care for conditioning or possible injury—and where NFL players themselves enjoy the experience.

Even when you get a little crazy, ideation works best when you have some purpose in mind to focus the exercise. Although you do not want to focus so hard on a particular customer need that you cannot expand your thinking enough to generate significant new value-creating ideas, you also should not venture so far and wide that you leave your business and company somewhere back over the receding horizon. But when a particular customer focus strikes you as too narrow, look for ideas that leverage your company’s current and developing competencies, that employ technologies from other industries within your grasp to master, and that embrace emerging technologies that could soon apply to your business or that one day might help you further your company’s pursuit of its chosen purpose. After all, when opportunities exist for a company to leap from iMacs to iPods to iTunes to iPhones to iPads as Apple did, you do not want to constrain your ideation to miss such game-changing opportunities.

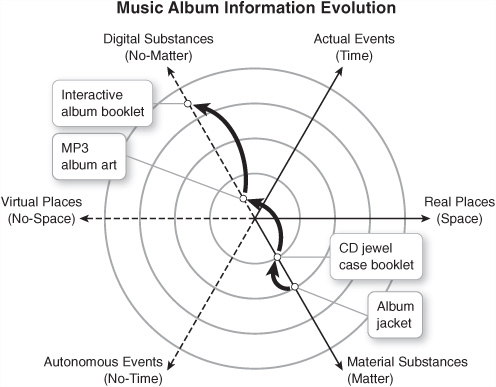

Playing with Substance

Consider the possibilities the Varying the Variables expedition presents as we illustrate several different offerings and their changes over time. We’ll start with an example that plays out only on the Substance dimension—transitions in music album art, as shown in Figure 11.6. In the days when music was most commonly sold as analog patterns carved in one long spiral on a vinyl disc—for those unfamiliar with such a strange thing, look up “gramophone record” on Wikipedia3—the cardboard album jackets became an advanced art form thriving on a little over one square foot. With the advent of the jewel case to hold digitized music on a compact disc, album-art real estate decreased to one-sixth its former size, with the front “cover” being a removable booklet of multiple pages.4 In one sense, this moved album art down the Substance dimension, providing less material to work with, at least as far as what is visible on the real estate of the shrink-wrapped jewel case is concerned. But this was only the beginning of what digitization wrought on album art.

The next step, from CD to MP3, broke the 1:1 relationship between the material media and the music. People now store multiple albums or songs on their digital memory devices, losing the physical medium for the album art and leaving only the miniscule thumbnail icon that may or may not, depending on the setup, display with a song listed on a hard drive or music player. But the virtualization of the album also held the solution to the problem, as digitally interactive album art arose on the Internet to bring a richer experience to the listener than was ever possible with the cardboard-based media of long ago. Users now can access interactive multimedia content, including artist videos, band photos and even “animated lyrics and liner notes,” as Apple boasts concerning its iTunes LP offering, which invited you to “experience a beautifully designed, interactive world right in your iTunes library.”5

Figure 11.6 Playing with substance

In time, as digital tablet devices like the iPad and universal Internet connectivity become commonplace, you will be able to view this album art anytime, anywhere—whether lounging in your favorite chair or seated in an airplane. Digitization brought with it a wave of enhancements to the music experience—indexing, searching, arranging, selecting themed playlists, and so forth, none of which was lost on Apple. What digitization took away from the physical it replaced many times over in the virtual.

Playing with Presence

Next, consider the evolution of groups communicating from disparate locations. The telephone, whether in the form of land lines, cell phones, or VoIP applications such as Skype, offers people the opportunity to meet virtually. Figure 11.7 plots the teleconference experience on the Experience Design Canvas. Note the dominance of digital substances and actual events. Real space reflects a small commitment to the location of the telecommunications device, though this becomes minimal when using a mobile phone compared to, say, a normal office environment. The phone device shows as a minor material substance factor. The notion that teleconferencing in its own small way eases the grip of time by alleviating the requirement that meeting participants gather together in one physical place gets reflected as a small dose of autonomous events. Finally, there is very little virtual place in the teleconference experience (just the tiny shared space over the wire, through the ether, or across the Internet).

Figure 11.7 From teleconference to telepresence

Now compare teleconferencing to telepresence, a much more experiential offering centered in Mirrored Virtuality. In addition to actual events, of course, virtual places and digital substances become the dominant variables, creating new customer value far exceeding that of teleconferencing due to not only the lifelike video presence of the participants but also the functionality of collaboration apps supporting joint participation in activities and the sharing of information.

Notice there is also, almost paradoxically, a greater intensity or role for real places due to the specialized rooms required to conduct a telepresence session. For the most part, this is not an added value to the experience, but rather a new customer sacrifice, because the attendees must gather in specific physical locations. Maybe one day Cisco, HP, or another supplier will replace the telepresence room with virtual reality goggles and ear phones to create an even better experience of “being there” without physically being there, freeing the participants to collaborate regardless of their physical location.6

Playing with Emotion

Telepresence illustrates how an increase in a variable may not actually add value to the experience, but rather can cause customers to sacrifice. Customer sacrifice is the difference between what a customer settles for and what he wants exactly. In any experience design pay attention to where you might be introducing such sacrifice, whether unintentionally or as a consequence of value added elsewhere, and further how you might eliminate sacrifices that customers encounter in current or competitive offerings.

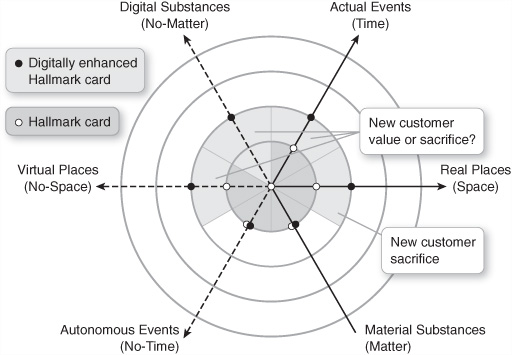

This notion of value versus sacrifice, or negative value, also comes out in Hallmark Cards’ Augmented Virtuality offering highlighted in Chapter 7, “Augmented Virtuality.” Hallmark did not have the benefit of the Multiverse when describing its new offering as Augmented Reality, but now that we have it, using the lens of the six variables yields a richer, more nuanced interpretation for both its traditional card-only offering and its new augmented offering.

The traditional card experience fits in a particular spot in the flow of actual events because it commemorates, celebrates, anticipates, or simply accompanies some, uh, actual event. Card givers often intend for the card-receiving experience to happen in a special place: delivered to one’s place of work to celebrate a milestone with coworkers, sent to a loved one’s home to be relished in an easy chair, dropped off as a blessing at a wedding, or given in person at a social gathering intending to elicit a spontaneous laugh. The material substance of the card itself contains the pictures and words that trigger the recipient’s imaginative and emotional response—serving this purpose not just on receipt but often many times over as the recipient views the card again and again.

But the pictures and words (including added personal inscriptions) often also activate an autonomous time and virtual place. The giver uses these elements to invoke particular emotions, typically of comfort, joy, or humor, that transport (we could say “teleport”) the receiver to a different time and place—memories of a pleasant past, hope of better times to come, a fantasy environment, or even a shared humorous space connecting sender to receiver over many miles and moments. Place virtualizes as time warps to bring the recipient to the remembered past or expectant future (and, yes, sometimes a thankful present, but one more intensely felt and appreciated). As you can see from the core plot of the Hallmark card in Figure 11.8, the traditional card experience, nominally residing in Reality, actually embraces not just three but five of the six variables, illustrating the richness of experience possible with greeting cards and other such social expressions!

Figure 11.8 Digitally enhancing the Hallmark Card

Now consider how Hallmark enhanced this experience with its Augmented Virtuality offering, where software downloaded from its website enables recipients to view an entertaining animation when the physical card is placed in front of a webcam. When given such a digitally enhanced card, a recipient actually has pretty much the exact same experience at first, and only afterward goes to his computer for the new, Virtuality-dominated experience. So the total experience actually involves a second, separate event that adds to the first, one of a significantly different nature. Here, the video displayed on the computer screen digitally creates a predesigned virtual place, rather than the virtual place existing solely in the cardholder’s imagination. It is a primarily entertainment experience with a linear structure, without the spontaneity of the traditional recipient’s autonomous flights of fancy. And if you happen to tilt the card too much and lose the video, on restarting the experience you must start all over again at the beginning. Moreover, this all must happen in front of a computer, with a functioning camera, after a not insignificant amount of time spent downloading the application to make the video work. Depending on the recipient, this add-on experience could have significant value—as it did with Joe’s daughters when he sent them ones for Valentine’s Day—or not be worth the trouble, for as the digitally enhanced Hallmark card is depicted in Figure 11.8, it clearly entails some new customer sacrifice.

Realize, however, that the current implementation is an interim step for what will certainly be possible in the future—and we applaud Hallmark for experimenting at this early stage in the technology’s development. Imagine the day when such virtual experiences become embedded in the physical cards themselves, eliminating the sacrifice of the virtual place and downloaded software on the computer. Card givers could then, for example, add customized digital substances, displaying pictures or videos of the recipient’s past or the recollections of friends and loved ones of their past lives together. How much better would the experience be to open the card and see a holographic video playing above the card—just like Hallmark Sound Cards already embed audio clips? Other possibilities abound, such as using an iPad as the social expression delivery mechanism, or expanding the material substance of the card, for very special occasions, to become some sort of glass-like cube containing the card’s message in the form of custom pictures, narration, and videos that play on touching the device, eliminating the card altogether while maintaining the social expression that emotionally connects giver and recipient together. Finally, how far away are we from artificial intelligence capabilities that would enable the card recipient to carry on a conversation with the holograph of a loved one, living or passed on? How much better might this expand and intensify the previous plain-old-card experience?

The card is only a medium through which to deliver a virtual experience, the story on the card and the emotions it evokes. The physical card serves, as it always has, as the personal memento that re-triggers the emotional sentiments when glanced at, as well as a public testimony that you have friends who acknowledge your uniqueness.

Playing Guitar

For one last example, consider the Guitar Hero World Tour video game introduced in 2008. It physically includes peripheral lead, bass, and rhythm guitars as well as drums and a microphone for vocals. Imagine the experience of five players gathered around a large-screen TV, several of them playing the digital renditions of real instruments while others perform as vocalists, as they lose themselves in the rhythm, mood, collaboration, and focus required to adhere to the pace of the game. This game, too, is nominally Augmented Virtuality, but a closer examination reveals that, like ARGs, it encompasses all six Multiverse variables, none of them producing much customer sacrifice. There is an element of autonomous time for those lost in their performance, the actual time of the music, the virtual place as portrayed on the TV display, the real place of the gathering, the material instruments and microphones, and the most dominant variable of all, the digital substance of music.

As indicated by its depiction in Figure 11.9, this experience has it all—Reality and Virtuality fused together (not to mention authenticity, immersion, emotion, and action), with all variables high in intensity. No wonder the game became such a hit! The interplay of all the variables immerses the players in a virtual place and flow in time by linking their physical bodies and minds in the activity of real-world playing and singing, bathing the virtual world in digital music. The emotional warmth of those gathered to engage in a common purpose shows in the players’ intense looks and glowing smiles. The visible feedback of the guitar player’s fingering of the frets extends his senses, spurs on his performance, and links him to the others who are organized in the overall context of the game.

Figure 11.9 Guitar Hero World Tour: fusing the real and the virtual

Let Guitar Hero World Tour further open your thinking to the diverse possibilities for designing digital experiences. Some may be “pure and simple,” like a singularly Virtuality or Reality experience, some may be augmented while anchored in Virtuality or Reality, and others may break the bonds of both of these realms to create an entirely new kind of experience.

Variable Guidance

However you use these examples and insights to bring your expedition to an end, learn to Vary the Variables the way children approach playing with LEGO building bricks: fiddling with the variables of the Multiverse, changing their magnitude and their configuration to see what discoveries you make, what insights reveal themselves, and what ideas arise. Consider it serious play.7

Varying the Variables takes idea generation for experience design to a whole new level. Keep in mind that although no authoritative formula exists for depicting the variables of experiences on the Design Canvas, it proves a superb catalyst for serious idea generation and even design initiation, if not refinement. With this in mind, here are some guidelines to enrich your capabilities in these areas:

∞ Know your experiential variables. Honing in on the variables of the Multiverse opens the door to a whole new perspective on the makeup of an experience. To employ this perspective, start by thinking of, and becoming very familiar with, the way each variable contributes to the whole experience. Become practiced in analyzing your own personal experiences. Become proficient at knowing how each variable acts to enlarge an experience, embellish its nature, boost its value, and enrich it to entice engagement.

∞ Put all the variables to work. Your company instantiates experiences from events enacted, places formed, and substances constructed. Each of these three dimensions consists of two variables to be both scrutinized in existing offerings and imagined in various configurations for possible new offerings. Always consider each variable’s inclusion, exclusion, and intensity relative to one another within the experience in question, its absolute intensity in consideration of the intention of the experience, and its relative contribution compared to other experiences.

∞ More is more. Look for opportunities to turn up the intensity of one or more variables of an experience. Challenge yourself to dial up one variable at a time in order of magnitude. How does this change the experience? What potential value does this create? And how might it be accomplished?

∞ Less is more. Refine the selection and intensity of some variable to create a pure experience. Eschew any variable that takes away from the essence of an experience, like deep-sixing your mobile phone before entering a health club for your workout or massage, or turning the voice off on your GPS navigator to enjoy the conversation with your passenger.

∞ Eliminate sacrifice. Minimize or even eliminate any unneeded, unnecessary, and unwanted variable (or aspects thereof). We pointed out in the Hallmark example the sacrifice the customer makes by having computer interactions as part of the digital experience. Target eliminating such sacrifices to clarify the experience.

∞ Mass customize the offering. Mass customizing eliminates customer sacrifice, and digitization enables mass customizing. So as we’ve emphasized before (and will again), seek to design Multiversal experiences to order, tailoring them to create customer-unique offerings that engage targeted senses, extend custom capabilities, and selectively evoke specific emotions.

∞ Context, context, context. Keep in mind that all experiences are personal in nature. The guest of an experience is its most essential contextual element. For example, the father of my (Kim’s) good friend recently visited the USS Arizona Memorial in Hawaii where his brother died in the opening days of WWII in the Pacific. For him, this place evoked an intense emotional response due to his loss over sixty years ago. Other guests come simply to learn more about a historical event that never touched them personally. Still others may view this place indifferently and be more drawn to watching the fish swimming over the sunken battleship than the memorial to those killed in battle. How can you design for each context? Each guest?

∞ Harmonize the variables. Be sensitive to how one variable of an experience affects the others. Have you ever, for instance, been to a promotional event where to give it gravitas the organizers erect some striking structure, such as stunningly massive columns? During the course of the event you go stand next to one of the columns, where a rap of your knuckles produces only a hollow sound from the obviously fake prop. All of the sudden the once authentic-looking column loses its luster, and you begin to notice the speaker and the rest of the event begin to look less authentic as well. Inconsistencies in the visual versus material aspects take away from the whole experience.

∞ Examine variable capabilities. Identify how the technologies associated with each variable enable and expand human capabilities in order to be aware of the various technology → human capability → value creation progressions involved. For example, we have seen many examples of value created by virtual substances (No-Matter) that enhance and extend our sensing, linking, performing, and organizing capability. What capabilities are associated with the other variables? How might you extend and enhance people’s capabilities?

∞ Explore the four possibilities for juxtaposing real and virtual variables to create new value in Multiversal experiences:

– Enrich the real with the virtual. Look for opportunities to add some virtual element to enhance the real experience. Augmented Reality has a host of examples, but the same can be done for other realms and configurations of variables. Just pick a real variable and look at its virtual counterpart for possibilities.

– Manifest the virtual in the real. Look for opportunities to bring the virtual into the real, like how 3D printing brings material substance to the virtual. What other types of opportunities exist to make the virtual real?

– Infuse the virtual into the real. Look for opportunities to instill the virtual into the real, to blend the two together for a more robust experience. ARGs and Guitar Hero do this to great extents. Where and how else might this be done?

– Embed the real in the virtual. We already do this, lots of it. That’s what Mirrored Virtuality is all about. But what other opportunities exist? How would the experience be more engaging by bringing all three Reality variables into Virtuality?

∞ Finally, iterate your ideation, definition, selection, and design. Performing multiple iterations yields ever more bountiful results. Though very practical, people rarely practice iterative inquiry, presuming they will be plowing the same ground twice for little or no additional gain. In actuality, iterative inquiry nearly always reveals significant, new, valuable ideas for anywhere from three to five, and sometimes even more, iterations. Intrepid idea explorers who have the patience, persistence, diligence, and courage to iterate through the same process multiple times will discover the most valuable gems.

When you follow these guidelines, your pool of ideas should be overflowing even more than following the Reaching through the Realms expedition.

Turning Possibilities into Opportunities

Note that your explorations build progressively from one to the next. Each one enriches the others as you build knowledge and insights regarding the possibilities and opportunities opening up to your company on the digital frontier. Through diligent pursuit of Multiverse ideation expeditions you grow your capabilities to first gain insights from the perspectives of each realm and then on to envision the power of each variable. These enable you to build foresight emanating from the promise of technology and to create tomorrow’s hindsight today through unfettered perceptions of what truly meeting your customer needs looks like.

While Reaching through the Realms searches and imagines to discover new possibilities, the Varying the Variables expedition depicts and designs to not only generate ideas but define new offerings. In this exploratory progression, the Multiverse expeditions get you beyond mere possibilities to newly formulated opportunities that—accompanied with perceptive analysis, excellent decision making, and flawless execution, of course!—can be designed and deployed to create economic value for your company.

In all your ideation efforts, complement your discovery of value by understanding the five genres of offerings identified in the Progression of Economic Value delineating the flow in customer value from commodities to goods and services and on to experiences and transformations. Then focus your opportunity search on where the greatest value can be created—seek to solve customer problems, identify their latent needs, find alternatives for them to use their time and resources in ways that improve their lives, extend their current capabilities, and enable them to do things they otherwise are not able to do. In a broad sense, these are the things humanity always has done with the technology available to it and invented by it. We now find ourselves on the digital frontier with the opportunities to create new value stretching out to and beyond our very imagination, just waiting to be discovered.