6

Virtuality

CRAFTING THE MOST IMAGINATIVE

Thus begins the very first computer adventure game in the world, Colossal Cave Adventure, created by Will Crowther in 1976.1 As crude as such a text-based game seems today, notice its salient attributes that continue through to the most wondrous of computer adventures today (which all owe this first game a great deal of debt):

∞ It creates a world in which the game action occurs, a world that does not exist in reality (although Crowther did model the environs after Bedquilt Cave, part of the Mammoth Cave system in Kentucky).

∞ That world does, however, have a real sense of place. (Where generic space is amorphous, place has presence.) A player can embrace and learn that place as if it were real, feeling as if he were there.

∞ It is immersive. While playing the game, everything else—the real room in which the player resides, the sights and sounds there, potentially even the monitor and keyboard on which it is played—recedes into the background and effectively disappears.

∞ It supplies a story, a narrative that sets the action in motion and creates drama.

∞ It grants agency. More than mere interactivity, the player has control and his actions have meaning, at least within the bounds set up by the game, making for a nonlinear narrative.2

∞ The player himself is represented in the game world in some way, even if only by the reference to “You.”

∞ The real experience of playing the game happens inside the player, in his own mind.

Think of any kind of game (not just adventure games, but battles, conquests, puzzles, and any other genre you can think of) played on any kind of digital computer system—Pong on an Atari, Doom on a PC, Pac-Man on an arcade machine, SuperMario Bros. on a Nintendo DS, Halo on an Xbox, Tetris on an iPhone, and on and on we could go—and these foundational characteristics all seem to be present: world creation, a sense of place, a feeling of immersion, narrative, agency, individual representation, and a real experience.

Crafting the Most Imaginative of Experiences

Moreover, these characteristics apply not just to computer adventures but to all of Virtuality.3 Rendering an experience inside of a digital computer means creating a world that does not really exist, but a world that does feel real enough to have a sense of place (even if it does not look like the real world in any way). The essence of Virtuality lies in how it immerses the mind, although generally not the body, in ways that free us from the constraints of Time, Space, and Matter. The individual sees himself inside the created world, interacting with and within it (even if the user/player/experiencer/person cannot change that place in any way, as with a work of art) in a way that creates a real experience within him.

This last characteristic applies to all experiences everywhere, whether formed in a real or virtual place. Experiences happen inside of us, as our reaction to the stimuli staged outside of us, whether the substance of that stimuli be material or digital. Experiences are memorable events that engage each person in an inherently personal way, whether the events enacted are actual or autonomous to our everyday lives and surroundings. So don’t make the mistake of thinking an experience must be based in Reality to be real! The research of Byron Reeves and Clifford Nass shows that “individuals’ interactions with computers, television, and new media are fundamentally social and natural, just like interactions in real life.”4

Of course, as we stressed in Chapter 2, “Reality,” the richest of experiences still resides in real life, and we believe always will. For although the essence of the realm of Reality is its sheer physicality—immersion in God’s creation, not the creations of Man—Virtuality, conceived in imagination and birthed in immateriality, enables experiences otherwise impossible in Reality.

Virtuality is not constrained by physical places, existing not in the real world but in the ethereal world of the Internet, or cyberspace. This now-old term derives from cybernetics, the study of communication or control, based on the Greek word cyber, meaning “to steer.” In the No-Space of cyberspace, however, it is not the body that steers but the mind, through its manipulation of No-Matter. For Virtuality is not limited by material things, being constructed of digital bits. Further, Virtuality is not bound by actual time, as it opens up to past times in the history of the world, invented times in possible futures of the world, or fictional times in cosmos incogniti that never were, are not, and never will be other than in our imagination. Even when a Virtuality experience remains tethered to the real world of the here and now—such as with social media—there remains an otherworldly sense of how time flows, taking advantage of the hyperlinked nature of the hypertext Internet to flit about in all possible sequences, multitasking to the max until time and space themselves recede and we seem to become more mind than body, more out there than in here, more immaterial than material.

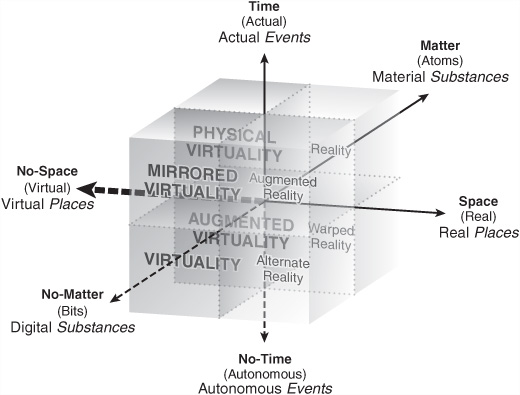

The Greek-derived term hyper, in fact, means “over, above, or beyond,” and its use serves notice that one is leaving Reality as we have always known it and entering a different kind of place, one over, above, or beyond. Think too of hyperspace, that fictional dimension where undiscovered laws of physics enable faster-than-light travel, which in turn enables travel through time. Such is possible only in Virtuality, the realm of [No-Time – No-Space – No-Matter] or [autonomous, virtual, bits], shown in Figure 6.1 where physicality recedes, mental activity ascends, and links to actual time fall away.

The Promise of Virtual Reality

Virtuality first captured the imagination in the form of Virtual Reality, a term popularized if not coined by Jaron Lanier, who was one of the pioneers of the head-mounted displays and data gloves associated with the concept. The goal was to replicate reality using digital technology, ideally with a verisimilitude so high that one could feel the technology melt away as the re-creation came to seem real, immersing the body, filling the senses, and engaging the mind. Research into Virtual Reality (VR) both inspired its loftiest depictions in fiction—the Holodeck of Star Trek (a completely realistic virtual simulation involving not only sights and sounds but smells, tastes, and tactile sensations) and the Matrix of The Matrix (where a complete simulation of reality was jacked straight into characters’ brains), among others—and in turn was inspired by these portrayals to reach higher, further, and realer.

While that vision remains remote still decades later, the first known depiction of a virtual environment reaches back over two millennia: the Allegory of the Cave in Plato’s The Republic.5 In this well-known story the ancient Greek philosopher held that most people were like prisoners who lived in a cave all their lives, bound by chains, seeing only the shadows thrown on a wall by some unseen light source. These shadows came to comprise their reality, for they knew nothing else. The philosopher, on the other hand, is like a prisoner set free, who comes to understand the true nature of the shadows: that they merely represent what is real and true existing outside the Cave. For Plato, these shadows were the material things that we can sense in the world, and the real and true things were not things at all, but ideas and ideals from which all else was but mere shadow. Of course, the irony—and the lesson—here is not that what seems real (the shadows) is virtual, but that what Plato says is really real (the ideals) is actually virtual, existing only in the collective mind of humanity!

The Reality of Virtuality

And the mind is a wonderful thing. It turns out that we do not need full immersion of the VR kind to participate fully in imaginative virtual worlds; we only need a representation of a world we can believe in, good enough that we can act as if it were real.6 Even a text-based environment, as we saw with Colossal Cave Adventure, suffices in this regard, although of course visual representations work even better by making explicit what the mind only imagines.7 The first virtual experiences that could earn the appellation “world” were text-based Multi-User Dungeons, or MUDS, which brought the live action role-playing games (or LARPs, mentioned in Chapter 5, “Warped Reality”) inside a computer where they could be played individually and accessed repeatedly, whenever desired. These moved from text descriptions to graphical representations over time, morphing into the awkwardly acronymed MMORPGs, massively multiplayer online role-playing games, such as World of Warcraft, Ultima Online, Everquest, Call of Duty, Battlestar Galactica, and Eve Online. These spawned open-ended places of exploration, creation, and conversation such as Second Life, There, The Sims Online, Cyworld, and Habbo Hotel, not to mention the intriguingly named Real Life Plus. And their progeny include virtual worlds designed especially for children, such as Webkinz World, Build-A-Bearville, Club Penguin, Virtual Magic Kingdom, American Girl’s Innerstar University, and LEGO Universe. Video games, too, create virtual worlds with a sense of place and sensation of the real, whether played on an arcade platform, a personal computer, a computer-based console, a smartphone, or any other digital delivery device.

What they all have in common, again, are the attributes mentioned above: world creation, a sense of place, a feeling of immersion, narrative, agency, individual representation, and a real experience. In other words, we don’t need the full promise of virtual reality to create Virtuality; we only need to create, in poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s immortal phrase, “that willing suspension of disbelief.”8 In this view, people let what actually is, Reality, wash away to believe the representation, Virtuality. Coleridge, however, did not quite get it right. In Hamlet on the Holodeck, Georgia Tech professor Janet Murray rightly comments on Coleridge’s famous expression:

But this is too passive a formulation even for traditional media. When we enter into a fictional world, we do not merely “suspend” a critical faculty; we also exercise a creative faculty. We do not suspend disbelief so much as we actively create belief. Because of our desire to experience immersion, we focus our attention on the enveloping world and we use our intelligence to reinforce rather than to question the reality of the experience.9

Creating Virtuality, then, requires fashioning a representation people willingly, actively desire to believe. It is a matter of creating belief.10 J. R. R. Tolkien, who knew a thing or two about fabricating worlds in which people could immerse themselves through belief, called his craft “Enchantment” and outlined how to go about it: “What really happens is that the story-maker proves a successful ‘sub-creator.’ He makes a Secondary World which your mind can enter. Inside it, what he relates is ‘true’: It accords with the laws of that world. You therefore believe it, while you are, as it were, inside.”11

And inside people go, tens of millions of them, with their numbers increasing every day. Such virtual worlds, Second Life in particular, became all the rage a few years ago as hundreds of companies followed, moving in-world to market their out-world merchandise. Few, however, bothered to truly understand the phenomenon or create anything but empty stores with no real experience. And so in the eyes of many it crashed and burned.12 As is so typical with high technology, virtual worlds were overhyped on the short term (with many worlds sure to go under, perhaps even Second Life itself), but almost certainly underhyped on the long term.13 Edward Castronova, the first economist to study the trend, predicts that eventually hundreds of millions of people, maybe a billion or more, will spend tens of hours every week inside virtual worlds, for “these two domains”—Reality and Virtuality in our terminology—“are in competition with one another.” “An exodus is under way,” he explains. “Time and attention”—the currency of experiences—“are migrating from the real world into the virtual world.”14

This migration of time and attention to virtual worlds applies not just to full-fledged renderings like Second Life, it also applies, perhaps even more so, to much less realistic but more easily played casual or social games, such as Tetris, Peggle, My Empire, and FarmVille. The latter game, from San Francisco-based Zynga, lets Facebook users set up and manage a simulated farm, with, at the time of this writing, over 215 million annual players, 20 million of whom check in on their crops and livestock every day.15 At the time of your reading, those numbers will certainly be much higher (and perhaps it will even be surpassed by its urban cousin, CityVille). As friend Dave Wright told Joe point-blank: “FarmVille has captured my wife.”

A key reason for the level of engagement all of these virtual experiences epitomize is, once again, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s concept of flow. Although discussed in Chapter 5, “Warped Reality,” in regard to that realm’s aspect of No-Time, flow applies just as much to Virtuality experiences (of all stripes and realms).16 For being “captured” need not be bodily; we only need some sort of avatar, some virtual representation of the real self that fulfills that fifth attribute of individual representation. An avatar serves as our virtual identity, representing who we are, whether via a mere camera view that says someone in particular is looking at the scene, a cartoon-like figure that performs actions, or a full-fledged virtual body that we may create, customize, clothe, and call pretty much anything we desire. In those virtual worlds with such extensive, customizable, and embodied avatars, if the creator proves an adept story-maker, then when our minds enter it, our avatars enable us to believe it, to see it as true. As anthropologist Tom Boellstorff says in his wonderful study Coming of Age in Second Life, “Avatars make virtual worlds real … they are a position from which the self encounters the virtual.”17

The Virtuality of Reality

The virtual worlds our selves encounter need not be solely fictional, invented, or hypothetical. You also can fashion representations of the real world to let people experience places they may not be able to visit physically or in ways they cannot experience materially. Think of all the websites layered on top of Google Maps, such as Globe Genie, from MIT graduate student Joe McMichael, where hitting the “Teleport” button takes you to a random spot on the seven continents, albeit virtually.18 Or even more experientially, consider Google Earth, a virtual globe where you can zip around and zoom in to any place in the world. Because Google’s done all the hard work of stitching together satellite images and other information to create a virtual 3D representation of the physical world, Google Earth has become a platform for all sorts of Virtuality experiences, from election results, blue state by red state, to the location of items for sale on Craigslist, home by home. In autonomous fashion it also provides historical imagery, seeing sites from present time back to the first available images in 1930, as well as a time slider to see the effects of the earth’s rotation over the past twenty-four hours as day and night shift across the globe.

NASA provides an open-source satellite view of the earth, World Wind, that people can browse and fly through, and Microsoft maintains its own offering called Virtual Earth. One of the latter’s most intriguing aspects is Photosynth, which at the street level stitches together numerous digital photographs of the same place into one navigable image. The resulting “synth” converts 2D photographs into a 3D synthesis that recreates the original, real-world place as a mesmerizing mishmash of days, times, lighting, angles, and resolutions.

Far more accurate and even more fascinating, CyArk uses 3D laser technology to scan and build virtual models of cultural heritage sites around the world. The nonprofit organization, founded by civil engineer and inventor Ben Kacyra of Orinda, California, desires to preserve and share sites that might otherwise be lost forever to erosion or disasters. Its lasers collect millions of measurements per hour as they scan such sites as Mount Rushmore, the Mesa Verde cliff dwellings in Colorado, the Piazza del Duomo in Pisa, Italy, and ancient Nineveh in Kacyra’s native country of Iraq. (All of CyArk’s projects are nicely laid out in a Google Earth mashup on its website!19) The vast collection of digital data should result in the most complete and precise 3D virtual models ever detailed, in effect enabling time travel, as Michael Kimmelman of the New York Times makes clear:

Through scanning, the experts can conjure up what objects looked like ages ago, in effect turning the clock back on ancient sites. They can simulate the effects of climate change, urban encroachment or other natural or man-made disasters on those same sites, peering into the future.

Given a proposal for a new building in a city like Edinburgh, they can also create virtual realities, almost microscopically accurate, so viewers might see what the building looks like from all angles in the place where it’s intended to go, including the shadows it might cast at different time of day….

A virtual past that never dies.20

Less accurate than any of the previously mentioned examples but equally appealing, people also create simulations (or “sims”) of real-world places inside of virtual worlds, especially in Second Life (or SL). These include re-creations of physical entities that exist in Real Life (or RL), such as buildings like the Eiffel Tower from Paris, Burj Al Arab hotel from Dubai, and the Arch from St. Louis; museums like the Exploratorium (the original museum of science, art, and human perception in San Francisco); and sims of cities like Seattle (complete with Space Needle), Berlin (after the wall came down), and New York (with numerous places recreated within SL, and where 9/11 commemorations now happen every year, demonstrating the ability to have authentic experiences in virtual places). Countries have even created virtual representations for diplomatic relations, with the Maldives placing the first known embassy inside SL.21 And taking full advantage of the No-Time dimension of Virtuality, there are even reenactments of historical places, such as Tombstone, Arizona, in 1899 where you—that is, your avatar—must wear suitable nineteenth-century clothing, and ancient Rome, or Roma, where your avatar is supplied a toga on entering the Customs House.

IBM made a place inside Second Life that exists nowhere in the real world: IBM Land. Here its executives meet with clients and give presentations; even CEO Sam Palmisano has been known to meet with clients here, avatar to avatar, as it were. In IBM Land its consultants create models of clients’ businesses to experiment (at very low cost) with process changes and assess the potential results. The company also created a Virtual Universe Community (VUC), which it uses to help clients conduct business inside virtual worlds, as well as for other business activities, including learning and training, teaming and collaboration, connecting and networking, scenario planning, and business process simulation. By using virtual worlds for conferences, brainstorming, and networking, IBM saves money and time while providing a platform that invites broad participation, with people from all over the world taking part at incredibly low costs compared to traveling to the same place at the same time.22

Simulation of Reality

IBM also created the CityOne game to help companies figure out how to use the offerings in its Smarter Planet initiative by trying them out in a “Real World Game” with “Real World Impact,” as its tagline attests.23 But the games and simulations IBM runs to help clients figure out how to improve their real-world businesses of course reside in Virtuality. Such simulations have long been around, particularly in the field of training, whether to prepare people for the manufacturing line, the cockpit, the operating room, a burning building, or the theater of battle. Digital technology now enables increasingly realistic, lifelike, and immersive experiences that can be replayed over and over, across myriad variations, until people become prepared to take on the tasks of real life. These all purposefully commoditize people’s experience in order to change them, and thereby shift up the Progression of Economic Value (see Figure I.1 in the Introduction, “Innovation on the Digital Frontier”), to become the fifth and final economic offering: transformations. By having people go through simulations of real-world experiences over and over and over again, their reactions become second nature, creating the ability to react instinctually to fast-changing, often life-threatening, situations.

The military specializes in this field, for the greater the danger of those real-life tasks, the greater the need to prepare. In 1999 the United States Army helped found the USC Institute for Creative Technologies in Playa Vista, California, to develop digital technologies that would prepare soldiers for far-flung battlefields. The directive from Army chief scientist Mike Andrews: “Build us a holodeck.”24 In concert with colleagues from Hollywood, ICT’s researchers continue to this day to get as close as they can to that vision, using interactive digital media to simulate such scenes as battlefields in Iraq, tunnels in Afghani stan, and the skies overhead both arenas. They also create simulations to prepare warriors to come back home, including one to help treat soldiers diagnosed with combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).25

The Army also effectively uses virtual simulations as recruiting experiences, including the highly effective America’s Army online video game and its Virtual Army Experience that it moves around the country. Interestingly, in collaboration with Pandemic Studios, ICT produced a commercial offshoot of its work, the popular Xbox video game Full Spectrum Warrior. This is not the same-old first-person shooter game as with so many other bloody titles; rather, the institute calls its products “first-person thinkers,”26 for it is all about making the right decisions at the right time. (And then you shoot.) Many object to such games, including the recruiting ones, but their impact extends far beyond the military. ICT now also produces “virtual humans, computer training simulations and immersive experiences for decision-making, cultural awareness, leadership and health.”27 One of the roles players take on in America’s Army is a medic, with the simulation so realistic that one such player, Paxton Galvanek, was able to serve effectively as a first responder in a life-threatening car accident. As Colonel Casey Wardynski, America’s Army Project director, now retired, noted, “Because of the training he received in America’s Army’s virtual classroom, Mr. Galvanek had mastered the basics of first aid and had the confidence to take appropriate action when others might do nothing. He took the initiative to assess the situation, prioritize actions, and apply the correct procedures. Paxton is a true hero. We are pleased to have played a role in providing the lifesaving training that he employed so successfully at the scene.”28

Virtual simulations increasingly provide an advanced platform for training and learning. Pro sports teams now apply the same motion-capture technology used in 3D films to create simulations of individual players to teach them better mechanics, or even “to train against life-size animations whose movements are based on statistics of specific opponents”; the real player, wearing 3D goggles, “runs, jukes and throws” as the virtual players chase him.29 Corporations increasingly use custom simulations and games to train their employees for the arena of business, or they take advantage of competitive games like EVE Online, Lineage, or Star Wars Galaxies to teach their employees leadership skills in fast-moving galactic arenas. As reported in a Harvard Business Review article, IBM found in a survey of its employees that such games were “surprisingly relevant to their day-to-day work”; three-quarters of the game players said they “could be applied to enhance leadership effectiveness,” with half having “already improved their real-world leadership capabilities.”30

In Learning in 3D, Karl Kapp and Tony O’Driscoll make the case for using, and provide a blueprint for, what they call “virtual immersive environments,” or VIEs, across myriad learning situations. They believe such simulations will eventually be done as a matter of course: “The Immersive Internet will become a worldwide virtual platform that allows people to immediately exercise their skills and abilities around endeavors that matter most to them.”31

Byron Reeves, the Stanford University communications professor mentioned earlier, extends this, with his colleague Leighton Read, to say that Virtuality should not just be used by workers to learn, but should apply to work itself. Echoing what Jane McGonigal said of alternate reality games, businesses should incorporate “the power of multiplayer games in the redesign of work, making work more engaging and making workers more productive.”32 This will happen because so much of work today lacks engagement, whereas “sophisticated online multiplayer games” require what businesses need: “extraordinary teamwork, elaborate data analysis and strategy, the recruitment, evaluation, and retention of top players in multiperson ‘guilds,’ the cooperation of people who have complementary roles that require coordinated action, player innovations that come from everyone, and decision making and leadership behavior that happens quickly and with transparent consequence.”33

Virtuality in Everyday Life

Although an Immersive Internet, replacing 2D pages on the World Wide Web with 3D environments, may very well be on the way, and multiplayer games within virtual worlds very likely will transform the workplace (more on that in Chapter 13, “From Design to Deployment”), the Web as we know it already comprises a place—ok, billions of individual but instantly interconnected and endlessly absorbing places—for Virtuality experiences. People spend prodigious amounts of time on social networking sites such as Facebook, MySpace, YouTube, Twitter, hi5, South Korea’s CyWorld, and China’s QQ, not to mention professional B2B sites such as LinkedIn and Chatter. They frequent social book-marking or news sites such as Del.icio.us, Digg, and reddit. They seek out blogs such as the Huffington Post, Gizmodo, Boing Boing, and Town-hall. They participate in online communities such as chat rooms, instant messaging, forums, and wikis.34 They play. They work. They live.

The Internet makes nearly everyone, everything, and everywhere almost immediately accessible to all of us virtually, eliminating geographic barriers and time differences to engender myriad options for connecting, creating, and collaborating. When Frances Cairncross so presciently said in 1997’s The Death of Distance that the communications revolution would yield, well, the death of distance, she noted that it meant (even more so than the coming of the telegraph had meant to nineteenth-century England) “the annihilation of … time” as well.35 For not having to travel means not having to spend time traveling. As the telegraph annihilated the distance and time of information, as the telephone annihilated the distance and time of voice, as radio and television annihilated the distance and time of entertainment, so the Internet annihilates the distance and time of experience.

No one has captured the No-Time, No-Space, No-Matter essence of the Web better than David Weinberger in his wonderful treatise Small Pieces Loosely Joined:

Our real-world view of space says that it consists of homogenous measurable distances laid across an arbitrary geography indifferent to human needs; the Web’s geography, on the other hand, consists of links among pages each representing a spring of human interest. Real-world time consists of ticking clocks and the relentless schedules they enable; on the Web, time runs as intertwining threads and stories…. Our “realistic” view of matter says that it’s the stuff that exists independent of us, and as such it is essentially apart from whatever meanings we cast over it like shadows; the matter of the Web, on the other hand, consists of pages that we’ve built, full of intention and meaning.36

So we seamlessly weave manifestations of Virtuality into our daily lives: not only the World Wide Web via Google searches and hyperlinks, but with mobile phones incorporating the ability to instantly access digital text, images, and videos sent and received from across the globe. We carry out more and more aspects of our everyday lives online. We e-mail, access, talk, text, twitter, blog, bank, search, shop, sell, purchase, pay, play, plan, track, travel, fritter, relate, love, enjoy, escape, learn, be. We experience.

Thus have our daily activities been transformed, and in so doing have transformed us. The World Wide Web is the Wild, Wild West of Virtuality. It is a digital mash-up of times and places, telescoping location and distance along with past and future into an ever-on, always accessible here and now.

Virtuality Unbound

Of course, in reality, if you think about it, all we can ever live in is an ever-on, always accessible here and now. That is the nature of real life. What digital technology does (for good and ill, it must be said) is intensify that life, increase its reach, and, yes, telescope what is accessible to make nearly everything within reach, virtually.

There is, however, an older way of moving beyond what lies physically at our fingertips, a way that predates digital technology: our imagination.

Long before the Internet made all information accessible—every book that has ever been published, every paper that has ever been written, seemingly every thought that has ever been thunk—we could read books and imagine. In our mind’s eye we could escape the humdrum of everyday life and see vistas unknown, travel to places unexplored, encounter dramas untold, and, with Plato, contemplate ideals unappreciated.37 Before the telephone, we could listen to the stories of others—true stories as well as made-up ones—and picture them in our mind, maybe dream of being the protagonist, the hero saving the day. Before radio and TV and movies—all varieties of Virtuality themselves, with the primary experience happening on a screen—kids could break free of the boundaries of parental expectations and communal constraints through play, unadulterated fun where anything can happen and often does. Before the personal computer and the PlayStation, before Nintendo DS and the iPhone, we all could compete in games defined by rules of our own making, or join in with others on well-worn pastimes with rich histories.

In each case you can see Virtuality at work. No, not Virtuality enabled by digital technology, but Virtuality still conceived in imagination and birthed in immateriality, enabling experiences otherwise impossible in Reality.38 Virtuality enacted by the autonomous events of No-Time, formed in the virtual places of No-Space, and constructed of the immaterial (if not digital) substances of No-Matter.39

As discussed in Chapter 2, “Reality,” the key characteristic of Reality is its sheer physicality, involving not just the mind nor only the body but the physical world that lies outside of them. With Virtuality, where anything is possible, the opposite holds true: its primary characteristic is its utter immateriality, an experience unencumbered by the physical world and existing only in our mind. Sure, the body never really goes away, but with today’s technology it primarily withdraws from the full torso to the sensory extremities: the eyes, the ears, and especially the fingertips.

The exact same remains the case with so many other experiences we do not typically consider being virtual worlds, such as those noted earlier: going to the movies; watching TV; listening over the telephone, to the radio, or live with other people in conversation or storytelling; playing; competing in games; even reading books, where words create meaning. As philosopher Pierre Lévy notes in his Becoming Virtual: Reality in the Digital Age, “Since its Mesopotamian origin the text has been a virtual object, abstract, independent of any particular substrate.”40 He applies this not just to fictional stories but to nonfiction as well, for “writing desynchronizes and delocalizes” and “has led to methods of communication in which messages are often separated in time and space from their source.”41 As just one handy example, we wrote the words on this page at a completely different moment and place than you are reading them. (And those reading them on any sort of digital reader have the added virtualness of seeing these same words nicely pixilated from their corresponding bits.)

But when it comes to fiction, to the creations of the imagination, recall what digital media Professor Janet Murray said about how we actively create belief: “When we enter into a fictional world, we do not merely ‘suspend’ a critical faculty; we also exercise a creative faculty.”42 We do not need digital technology to exercise that creative faculty, but it intensifies our creativity, increases its capabilities, and maximizes its realization to make anything that can be dreamt experienceable, not only in our imagination, but visually, audibly, and increasingly through the other senses as well.

And when it comes to imagination, the possibilities are infinite.

Applying Virtuality

Virtuality is indeed the realm that most takes advantage of imagination, for its essence is again its utter immateriality, unencumbered by the physical world, communicated through a screen but existing only in the mind. Although we provided no principles for the other anchor realm of Reality, for it seemed, well, redundant,, it certainly seems appropriate here to do so for Virtuality. So embrace these principles to bring the power of No-Time, No-Space, and No-Matter to your offerings:

∞ First, envision how you can make the material immaterial initially in your imagination, and then through digital technology.

∞ Similarly, envision how you can make the real virtual by using digital technology to create places that do not exist in the physical world.

∞ And then of course envision how you can make the actual autonomous by playing with time. Review all the ways we discussed for doing so at the end of Chapter 5, “Warped Reality,” but recognize too that digital technology makes it so much easier to go into the past or future while enabling whole new ways, such as the time-shifting available with DVRs, or the ability to instantly pause the action and then pick up right where you left off as with most any computer game.

∞ Embrace the seven foundational attributes of Virtuality discussed at the beginning of the chapter that characterize nearly all of Virtuality:

– World creation: Create a virtual world, in particular one with “worldness,” to use Celia Pearce’s term, “a sense of coherence, completeness, and consistency within the world’s environment, aesthetics, and rules.”43

– A sense of place: That world should not be generic, amorphous, or indistinct, but should have the feel of the real about it.

– A feeling of immersion: Make Reality recede as Virtuality advances.

– Narrative: Enact a drama through imaginative storytelling.

– Agency: Give the customer control of his own destiny and thereby let him become the hero, or at least a hero, of the story.

– Individual representation: Provide the means for the customer to represent himself virtually, via some sort of avatar.

– Real experience: Recognize that the experience customers have inside their minds are real—even if the substance the experience is made out of is immaterial, the place in which it happens is virtual, and the events autonomous—and therefore work hard to create belief, providing touch points of Reality for them to grasp.

∞ Go beyond these foundational attributes to incorporate other aspects characteristic of state-of-the-art Virtuality experiences:44

– Three-dimensional: Although text-based representations no longer cut it, even 2D graphical worlds look positively primitive; Virtuality experiences should as much as possible visually look like real, three-dimensional places.

– Persistence: To go from mere game to fully realized world, the place must live on, even when any particular customer exits the world.

– Embodiment: Avatars come to not just identify people but to represent their identity through an emotional bond.

– Sociality: We are not alone; we are immersed with and interact with (the avatars of) other people. In almost all multiplayer games, it takes multiple players to achieve any goals of significance.

– AI-populated: We also are not alone in that many characters are in fact “bots,” powered by artificial intelligence to enhance the play experience.

– Contributory: Individual customers shape the virtual world, adding to (and sometimes subtracting from) it while affecting the experiences of the other people within it.

– Explorable: Even in first-person shooter games players can go where they want at the pace they want.

– Rule-bound: The world abides not just by the rules of physics but by the rules of their creators to enact the social environment they desire; failure to abide by them can result in some cases in death (or even worse, expulsion).

– Market-based: An internal economy—often with exchange rates to the real-world economy—allows people to buy and sell offerings found in-world or created from their own imaginations.

– Reputation: Avatars become known for what they have done, what they can do, what they know, and who they are, often via ranks and levels that immediately identify them to others.

∞ Go even further to consider attributes not yet there, but coming in the labs and on the horizon:

– Accessibility: Anywhere, anywhen, anyhow from wherever people happen to be, whenever they want, using whatever device they wish.

– Fully sensory: Virtual worlds remain primarily visual, with the ability to engage the ears via voice only a recent addition; tactile is next up, and then we will see what applications, if any, await the ability to taste and smell.45

– Emotive AI: Characters powered by artificial intelligence will eventually be able to respond emotionally, not just logically, to the cues given them.

– Natural: Keyboards and mice will eventually go away as we increasingly interact via gestures, voice, and even thought.

∞ But do not stop there. We are not trying to accumulate a definitive list but to spark your creativity and imagination. So seek out other attributes, attributes that no one else has thought of, attributes that emerge only with time, ingenuity, and the expansion of technological capability.

∞ With all of these as your toolbox, now think about how to re-create reality virtually, creating customer value using such platforms as Google Earth, Google Maps, or Microsoft’s Virtual Earth. Or your own.

∞ Simulate reality as well, providing the means by which your customers can learn about what is important to them before encountering it in Reality.

∞ Turn your attention from your customers to your workers to employ games, virtual worlds, and other forms of Virtuality as the means to run your business.

∞ Embrace the everyday, for you do not need to create an entirely new virtual world for your customers or your employees; you can make countless improvements in all the ways we already, as people, incorporate Virtuality into our lives.

∞ Understand that anything you can digitize you can customize; once something is represented in zeroes and ones, those ones can be changed instantaneously back to zeroes, and vice versa. So seek to customize anything and everything that makes sense (recognizing that not everything will), from avatars to interactions to the virtual worlds themselves.

∞ Use your imagination. Virtuality existed long before digital technology, and today as then it exists solely within the imagination. The possibilities may be endless, but the explorers are many; use your imagination to find the right possibilities for you, for your customers, for your company.

∞ And then create belief.

Game designer Harvey Smith says the most immersive experiences depend on good design and the ability to create a coherent and believable game world, not on fancy technology: “Despite all the gadgets that are now available, he says, ‘nothing is as immersive as a good book.’ “46 Acknowledging that a good book is a gadget of Virtuality, you still have nothing without belief. By getting your customers to actively create belief within your Virtuality offerings, you can create the value they increasingly seek on the digital frontier, becoming their guides in leading them to cosmos incogniti never before imagined.

The Realms of the Virtual

A counterweight to Reality in the Multiverse model, Virtuality anchors the Realms of the Virtual, depicted in Figure 6.2. The other three realms to be discussed—Augmented Virtuality, Physical Virtuality, and Mirrored Virtuality—all take this realm as their starting point, as each revolves around the No-Space axis encompassing virtual places. These realms each have their roots in Virtuality, which (as with the Realms of the Real introduced in Chapter 2, “Reality”) stretches out to encompass aspects of its opposite anchor, in this case Reality: shifting from No-Matter to Matter yields Augmented Virtuality, swapping No-Time for Time produces Mirrored Virtuality, and substituting both variables engenders Physical Virtuality.

It again would be just as accurate to say that Reality reaches out to pull a Virtuality-based experience in its direction by flipping appropriate dimensions from Virtuality-based to Reality-based: from bits to atoms for Augmented Virtuality, from autonomous to actual for Mirrored Virtuality, and then flipping both for Physical Virtuality. Creating experiences in these four realms all involve making virtual places, although some enact autonomous and some actual events, and some construct with digital and some with material substances. So even though the next three realms all maintain the texture of the virtual about them, they each take on one or more facets of the real and thereby provide even further opportunities for discovery.