4

Alternate Reality

CREATING AN ALTERNATE VIEW OF THE REAL WORLD

![]()

In early August 2004, the alternate reality game I Love Bees gave its online players, over 600,000 in number, their first real-world mission. On a web page that had previously presented recipes for the fictional heroine’s Saffron Honey Ice Cream and Bee-licious Chocolate Chip Cookies, a new set of tantalizing ingredients appeared: 210 unique pairs of Global Positioning System (GPS) coordinates; 210 corresponding time codes spaced four minutes apart and stretching across a twelve-hour period in the Pacific Daylight Savings Time zone; and a central timer counting down to a single future date: 08/24/2004.

There were no further instructions provided. The I Love Bees (ILB) players were given no goal, no rules, no choices, no resources to manage, no buttons to press, no objects to collect—just a series of very specific, physical locations and an impending cascade of actual, real-time moments. Taken together, what were these ingredients supposed to yield?

For two weeks following the initial appearance of the GPS data set on <http://www.ilovebees.com>, interpretation of its meaning varied greatly among the ILB players. There was no early consensus about what ILB’s designers wanted the players to do with these coordinates, times, and date. An explosion of creative experimentation with the data ensued. Some players plotted the GPS points on a United States map in the hopes of revealing a connect-the-dot message. Others projected the earthbound coordinates onto sky maps to see if they matched any known constellations. A particularly large group collected the names of the cities to which the 210 points mapped and then tried to create massive anagrams and acrostics from them. A smaller group decided to average the two numbers in each pair of coordinates and look for an underlying statistical pattern across the set.

Meanwhile, many players began visiting the locations nearest them and taking digital photos, uploading them to the ILB community online to see if a visual or functional commonality across the sites would emerge. Others without digital cameras carried out similar scouting activities and filed text-based reports, hoping to help uncover the secret message signified by the coordinates. Among this growing scouting group, numerous competing patterns emerged: The coordinates all pointed to Chinese restaurants, several players suggested—or mailboxes, or video game stores, or public libraries.

For a short while, the potential for plausible readings of the GPS coordinates seemed both inexhaustible and irresoluble. However, as the 8/24/2004 date loomed closer, and after tens of thousands of speculative posts on dozens of Web forums, a critical mass of players finally converged on a single interpretation: The GPS data set was not a puzzle, or a clue—it was a command. The designers were instructing players just to show up at the locations at the specified times and wait for something to happen.

And so, on August 24, swarms of “beekeepers” (a nickname many of the ILB players adopted) showed up at nearly all of the 210 locations, expectantly hovering in groups of a dozen or more. At the coordinates, the players clustered together laden with laptops, cameras, PDAs, cell phones, and anything else they thought to bring just in case, waiting to find out exactly what they were supposed to do. They explained to inquisitive passersby, “We’re playing a game.” The core mechanic of which appeared to be: Go exactly where you are told to go, and then wait for something to happen. Don’t make meaningful decisions. Don’t exercise strategy. Don’t explore the space. Just go, and wait for further instructions.

This is a game?

Indeed, it is. For many gamers, the August 24th I Love Bees mission was their first introduction to a new mode of digital gaming, one that centers on real-world, live action, performance-based missions.1

Whether or not this new mode of digital gaming—alternate reality games, or ARGs, here ably described by Jane McGonigal, the world’s foremost authority on them (and “puppet master” for I Love Bees, the ARG used to promote Microsoft’s Halo 2 videogame)—appeals personally to you or not, do recognize what a momentous experience it was for the players, who eventually did, as a group, figure out what in the heck was going on, and what it meant.

If you have not experienced an alternate reality game firsthand, it may not be the easiest experience to grasp. New media developer Asta Wellejus, of Copenhagen-based The Asta Experience, told us the best way she’s found to describe them is like this: “An ordinary virtual game is like Alice going down the proverbial rabbit hole where she enters a virtual world totally unfamiliar to her experience in the real world. An ARG takes dynamite to the rabbit hole and blows it up, letting all that virtual activity spill out into the real world, and makes the distinction between reality and the game world disappear. The game is now alive.” (Not coincidentally, ARG designers call the incident that begins the game the “rabbit hole.”) Thus, computer-based games can now be taken out of the terra nova of Virtuality and played out on the terra firma of Reality.

Creating an Alternate View of the Real World

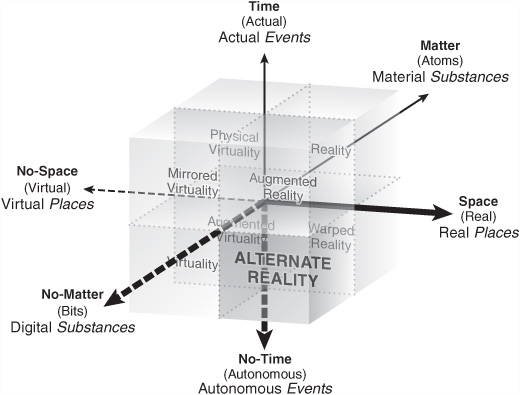

In terms of the Multiverse, Wellejus’ description perfectly depicts the entire realm of Alternate Reality, which takes otherwise virtual experiences and plays them out in the real world. For although a Realm of the Real, as seen in Figure 4.1 it lies next to Virtuality, encompassing virtual experiences shifted from No-Space to Space, from a virtual to a real place. The resulting superimposition of the virtual onto the real creates an alternate view of the physical reality.

So the essence of Alternate Reality involves using Reality as a digital playground, changing the way people perceive, and interact in, the real world via a superimposed, virtual narrative freed from the bonds of actual time. It is enacted as a series of autonomous events, not just by the company but the participants themselves, who interlace it with their everyday lives as they collectively work to solve the mystery and bring about a resolution, their very actions affecting the direction and intensity of the nonlinear narrative. Although the I Love Bees command to be at particular locations on a specific date smacked of actual Time, players at each of the GPS-specified locations discovered payphones that all rang successively. Answering the calls yielded individual snippets of a five-hour serial radio broadcast chopped up and spread out, which then had to be pieced together to solve the puzzle in autonomous No-Time fashion.2 As media expert Henry Jenkins notes, an ARG “depends on scrambling the pieces of a linear story and allowing us to reconstruct the plot through our acts of detection, speculation, exploration, and decryption.”3

Because of this extreme level of involvement, participants take ARGs very seriously. This flows from the philosophy (or conceit) that, no matter what you may think, “This is not a game” (known by players as “TINAG”).4 ARGs are becoming more and more widespread, with the Alternate Reality Gaming Network, dedicated to sniffing out new this-is-not-a-game games and providing a central resource to playing them, listing eleven ongoing games at the time of this writing.5 The first widespread ARG was The Beast, designed as a marketing experience for Steven Spielberg’s movie A.I.: Artificial Intelligence, and to this day companies primarily employ ARGs to market offerings—Audi, for example, created The Art of the Heist to promote the launch of its A3; this ARG involved players tracking down actual A3s in the real world to secure clues.6 But they also can be offerings unto themselves. Perplex City (say it three times fast), from London-based Mind Candy, offers cash prizes (£100,000 for its first contest) but makes money by selling cards that provide additional clues beyond what can be learned for free. Sean Stewart, the lead writer for The Beast and I Love Bees both, also writes novels, and using the knowledge gained from his work on ARGs now uses “websites, phone numbers, emails, and other ‘fourth wall’ techniques [that break the “wall” between performer and audience] to create uniquely interactive stories.”7

Or consider the offering Walt Disney World uses to spice up its least exciting place for the younger set, Epcot. The Kim Possible World Showcase Adventure (named after the eponymous TV show teenager on the Disney Channel who saves the world from evil villains when not going to school) puts youngsters in the role of detectives, who must join together to save the world themselves. The World Showcase in Epcot—a collection of pavilions demonstrating arts, crafts, and foods from around the world—provides the physical backdrop to the Alternate Reality experience, with kids given top-secret “Kimmunicators” (modified cell phones) that guide their journey, providing clues of where to go, who to talk to, what to encounter, and, finally, how to come together as Team Possible to save the world. While parents and others unaware enjoy learning about the world, those who play the adventure have a completely different experience in the same place and time, although in keeping with the autonomous nature of Alternate Reality, according to Disney the “Kimmunicators even recognize when a team has broken away from the action—even secret agents need ice cream breaks—and will alter your mission accordingly.”8

Beyond ARGs

Of course, ARGs do not provide the only way of embracing Alternate Reality—they give the realm its name but remain only a subset of the possibilities here. Closely related are these other forms of gaming:

∞ Pervasive games, such as Killer, where you and your fellow players take on the roles of undercover assassins, have “one or more salient features that expand the contractual magic circle of play spatially, temporally, or socially,” according to media culture expert Markus Montola.9 He goes on to relate these first two features in ways immediately recognizable as Space and No-Time thinking, referring to spatial expansion as using the “whole world as [a] playground” and temporal expansion as going outside “the proper boundaries of time,” and also acknowledging how digital technology, particularly that arising from Augmented Reality, is “a perfect way of adding game content to the physical world.”10

∞ Fantasy sports, such as Rotisserie baseball, fantasy football, and so forth, are games in which players create their own teams of real-life players, but they distribute them throughout the fantasy league in ways that in no way resemble the actual teams and leagues. They then use computers to compile the statistics of the games played at various days and times to create their own, alternate universe of a game, and eventually an entire season, based on how their players did.

∞ Scavenger hunts pit individuals or groups against each other to find the right spots in the real world based on clues coming in from the virtual world. Boston-based SCVNGR, for example, describes its offering as “a geo-gaming platform that enables anyone to quickly and easily build location-based mobile games, tours, and interactive experiences that can be enjoyed from any mobile device.”11 Founder Seth Priebatsch says he wants “to build the game layer on top of the world.”12

∞ GPS games are location-based games such as those provided by LocoMatrix of the United Kingdom, which claims that with its platform for “free-roaming games,” downloaded on your GPS-enabled phone, “planet earth’s a playground” (as the video on its home page attests).13 Games, including chasing, racing, and strategy games, can be played solo or with friends at a park, on the beach, or in any open space. LocoMatrix emphasizes that its games are “not on your mobile” but played “with your mobile” and that it “takes gaming away from the screen and into the real world.”14

∞ RFID games use radio-frequency identification chips rather than GPS to be location-aware. Netherlands-based Swinxs offers a self-contained gaming console with RFID wristbands that kids (generally younger than would participate in GPS games) can use indoors or outdoors to play such games as tag, relay, hide and seek, musical chairs, and even to take educational quizzes. As with LocoMatrix, the kids can even design their own games, in this case by connecting the console to a PC.

∞ Geocaching is another form of location-based game that Seattle-based Groundspeak describes as “a high-tech treasure hunting game played throughout the world by adventure seekers equipped with GPS devices” used “to locate hidden containers, called geocaches, outdoors and then share [their] experiences online.”15 The company, which popularized the activity, goes on to say on its official website that there are over 1.2 million geocaches around the world, with 4 to 5 million geocachers out looking for them.

∞ Geoteaming is an offshoot of geocaching used for business team-building. Its official website describes it this way: “Equipped with your cunning and the coolest high-tech toys—GPS receivers, Pocket PCs, two-way radios, and digital cameras—you and your team strike out on a fun-filled mission to find hidden caches. It’s a treasure hunt where the riches you take away are more than just prizes—they’re transformational lessons that apply to how your team works in your company environment.”16

Outside of gaming but in keeping with fun, consider GoCar Tours, which operates yellow go karts (tiny four-wheeled, two-seat vehicles) equipped with GPS-powered narration systems for tooling around tiny-car-friendly places in the United States as well as Lisbon and Barcelona. Its website description makes clear the No-Time, No-Matter nature of the real-world experience:

It’s a tour guide … a talking car … a trusty co-pilot … and a local on wheels.

GoCar is the first-ever GPS-guided storytelling car—and it’s available to rent right now!

Leave your guidebook behind and see the San Francisco, San Diego, and Miami most visitors never see. Hop into a GoCar and let this little yellow car take you on a guided tour of these fantastic cities.

Your clever talking car navigates and shows you the way—but that’s not all. As you enjoy the drive, it takes you to all the best sites and tells the stories that bring these cities to life.

These cars are smart. An on-board computer and a GPS-system do the thinking so you can actually relax and take in the beautiful cities.

The GoCar takes you to spectacular places few visitors get to see. It’s like having a local show you around. And this little car can go where the tour buses can’t.

Best of all, the adventure happens at your pace. You can stop for photos, take detours, grab a coffee or break for lunch. (You’ll actually be able to park!) Or you can blaze your own trail and explore the city streets, neighborhoods and parks on your own.17

With GoCars, people in effect randomly access any site they wish in any order and at any pace, a decidedly nonlinear activity relative to tour buses and other such constrained modes of visiting a destination.

Real-World Playgrounds

Notice how in almost every example inhabiting this realm people learn about something, whether it is the route of their traveling, how to traverse the landscape, clues that help solve a puzzle, where caches are located, or information about the other members of a team. Our favorite Alternate Reality offering gears itself specifically to the task of helping kids learn—with the great added benefit of getting them exercise—using actual schoolyard playgrounds as its real-world location of virtual activity. Lappset Group Oy, a manufacturer of playground equipment based in Rovaniemi, Finland, decided to add intelligence to its offerings via its SmartUs line of interactive playgrounds. Kids carry around RFID-enabled iCards recognized by the central console—the iStation—and various iPosts placed around the schoolyard. Kids might decide to play an adding game, for example, where the iStation tells them to add up to a particular number, say, 27. They then start running to all the iPosts to see what numbers they represent via their iCards. One might be +7, another -3, a third +4, and so forth. So they have to keep running to the posts, which change the totals on the cards whenever they’re read, until they execute a sequence that adds up to 27. The first kid to do so wins the game, and then off they go to play another, whether based in math, geography, history, or another subject. The iStation loads results into the Scorecard so kids can keep track of their results for long-term comparisons, determining their progress, and of course bragging rights.

They can also play other games using the iGrid, a jump mat placed in front of the iStation where each point in the grid can have different meanings in different games. Kids can even define their own learning games in the classroom, upload them to the iStation, and then play them with their friends. In this way SmartUs fuses gaming and digital technology with physical playgrounds and equipment to create a new generation of playful, active learning environments. While participants—not only children but often their parents on weekends, with other setups geared to keeping elderly adults as active (and as lean) as possible—run and jump and climb, they also solve puzzles, search for clues, and find solutions that enhance their learning, all in an atmosphere of compelling and competitive interactive play with all of its aspects of No-Time—enacting nonlinear sequences, starting and stopping, and so forth. Why, even recess is an autonomous respite from the otherwise linear sequencing of the school day! More than 70 schools across Europe now have Lappset digital equipment—not including its new Lappset Mobile Playground aimed at teens—and as its Managing Director, Juha Laakkonen, told us, “With SmartUs, schoolyards become a new classroom and a more diverse teaching facility—places where play, exercise, and learning all come together.”

Consider another playground of sorts for kids and adults, the DigiWall from Digiwall Technology AB of Piteå, Sweden. It is a digitized rock-climbing wall, which the company calls a “gigantic computer game in the form of a climbing wall”18 and sells to amusement parks and other attractions. Each hold in the wall is connected to a computer and comes with lighting and audio effects. This enables groups of people to use the DigiWall to play games, from seeing how many holds they can tap as they light up to a memory game in which they have to find matching holds that emit the same sound. Players can even play Pong with each other as the holds light up in sequence to simulate a moving ball, and when not in use the DigiWall can be programmed to play a light-and-music show for passersby.

As with SmartUs, DigiWall takes a reality-based experience, a climbing wall, and constructs digital substances to amp up the experience and thereby make players more active. They also both share the No-Time aspect inherent in games, which can be started and stopped, reined in or extended, and even frozen during a time out. They generally have a degree of autonomy that other, more natural and less rule-bound forms of physical space do not. Tom Chatfield points out “the sheer, changeless otherness of gaming, and its strange relationship with passing time” in his book Fun Inc. “To enter into the world of a game is to visit somewhere unfallen and ageless, where what you do and experience seems to occupy a special, separate kind of temporality; and where the passage of time in your own life leaves no mark.”19

From Actual to Autonomous Events

Realize, too, that this shift from actual to autonomous events distinguishes Alternate Reality from the adjacent realm of Augmented Reality, which both share the variables of digital substance and physical place. That means that if you can take the technology used to augment reality and then add a dimension of playing with time in some way, you can use that very same technology to alter people’s view of the reality before them! While Locomatrix, for example, refers to its technology as Augmented Reality, its No-Time games really belong in Alternate Reality. Sydney-based MUVEDesign, founded by virtual design expert Gary Hayes, is releasing a smartphone-based game called Time Treasure in 2011, which it describes as a “location based augmented reality story game” that, due to its “ten layers of time from 2050 back to 5000BC,”20 also plants it firmly in this alternate realm. People can also use “Reality Browser” Layar to “see” into the past or future, with layers to perceive what the Coliseum looked like in ancient times from your position in present-day Rome, for example, and to envision what the Market Hall in Rotterdam will look like when completed as you stand before the construction site.

Similarly, the Jurascope that ART+COM developed to animate dinosaurs in a museum becomes a “timescope” when used to simulate traveling back in time. In Berlin, where very few remnants of the Berlin Wall remain today after absolutely defining the divided city for so many decades, an installation enables people to digitally reconstruct where it was located and what it looked like. They can even select among various dates to see how the Wall changed over time, with the timescope “superimposing historical photos and films at exactly the location where they had been shot.”21 Similarly, the timescope also allows people to peer into the future by, for example, seeing how a building will change as it undergoes construction.

Note a key difference between these two implementations: with the timescope users must remain stationary, whereas with Layar they can move around. Mobility proves key to most Alternate Reality offerings (even when confined to a playground or a location such as Epcot’s World Showcase), for they exploit the technological capabilities of smartphones—cameras, video displays, accelerometers, compasses (magnetometers), GPS sensors, and Wi-Fitriangulation (where GPS doesn’t work well, such as in urban centers). That means the entire world comes into play, such as with the Gigaputt game from Brooklyn-based Gigantic Mechanic, which defines a virtual golf course from wherever you physically stand, letting you and up to three other buddies play it by using your accelerometer-equipped smartphone as the club handle. Gigaputt measures your swing and plots the resulting path of the ball across your neighborhood, urban streets, a park, or wherever you happen to want to play. As journalist Peter Wayner notes in the New York Times, “Everything in the game will unfold in the imagination of the players who might look a bit mad to everyone else on the street…. With these new tools, designers are building mystical realms, orienteering courses, immersive fictions, and parallel universes in a way that may or may not have anything to do with the world around them.”22

Affecting the Real World

What if companies squarely aimed Alternate Reality experiences at the world with the purpose of actually changing the real world in which they play out? Doing exactly that, on a regular basis, is the mission of our able ARG guide, Jane McGonigal. Her talk at the 2010 TED conference, “Gaming Can Make a Better World,”23 outlined how she wants to bring the skills, capabilities, and, most importantly, the time of gamers to bear on the problems of the world. She put her own skills where her mouth is by helping design a 2007 ARG called World Without Oil for San Francisco-based Independent Television Service (ITVS). Its aim: to see how society might react to and solve—just like the usual fictional ARG puzzles—a global oil shortage.24 Superstruct, a 2008 endeavor created in her role as director of game research and development at the Institute for the Future in Palo Alto, asked players to imagine the world in 2019, what tribulations they would face, and then what they might do to solve those issues, for “this is about more than just envisioning the future. It’s about making the future.”25

McGonigal went even further in a Harvard Business Review opinion piece by asserting to business executives that Alternate Reality should become “the New Business Reality”:

Although commercial ARGs are, in relative terms, a niche entertainment genre involving several million players worldwide, their enterprise counterpart could eventually become a significant platform for real-world business—in essence, the new operating system.

Why? ARGs train people in hard-to-master skills that make collaboration more productive and satisfying…. Using these skills, players amplify and augment one another’s knowledge, talents, and capabilities. Because ARGs draw on the same collective-intelligence infrastructure that employees use for “official” business, games will map directly to a familiar reality—no translation required.26

We should indeed see more of business played out in Alternate Reality, whether in forecasting, strategy, or even innovation exploration. “In all these cases,” McGonigal suggests, “business leaders will become the vital puppet masters, guiding collaboration, introducing complicating variables, and helping focus players’ attention in promising new directions,” resulting in “an ARG-based operating system that amps up collaboration in the service of strategy.”27

So Alternate Reality can also mean exploring alternate possibilities for the future of the real world and determining the best path in which to go.28 Then the “this is not a game” activity really will not be a game.

Applying Alternate Reality

Whether used as a marketing experience, a playful offering, an active learning experience, a strategic tool, or as one of myriad other possibilities that have yet to be innovated, Alternate Reality takes a virtual experience and shifts it over to the real world, making participants physically active in solving puzzles or discovering solutions. Its essence lies in constructing a digital experience and superimposing it onto a real place to create an alternate view of the physical reality. It blends the richness and sensations of the real with the power and complexity of the digital to challenge and involve participants in play environments where they learn almost every step of the way. Follow these principles to determine what role it can play in your business:

∞ As with Augmented Reality, use the real world as the background for the experience—but keep it in the background, only rising to the fore when focused on the real world itself, as in McGonigal’s plea. It is a Reality-based experience that flips not one but two variables—Matter to No-Matter and Time to No-Time—to yield new creative possibilities.

∞ With Alternate Reality, as its name implies, create an alternate view of physical reality. So what physical reality do you own or can you make into a digital playground? And what alternate views of that reality would create value for your customers?

∞ If you already are in the playground business, think about how to use your playground (by you or by others) for an Alternate Reality experience. Here think broadly, including in the definition of playground not only literal playground equipment like Lappset makes or the schools and parks it sells to, but also amusement and theme parks, golf courses, tour operators, tourism areas, urban districts, stadiums, and any other such physical places; even experientially active restaurants such as ESPN Zone or Dave & Buster’s plus outdoor-based retailers such as REI, Cabela’s, or Bass Pro Shops could take advantage of this realm. Such business venues as educational and learning places, conference centers, trade shows, and executive briefing centers should also closely examine this realm to create innovative offerings.

∞ Manufacturers of toys and other offerings for kids—think LEGO, Mattel, Fisher-Price, Topps—should look to make playful goods the basis for playful Alternate Reality experiences. If Walt Disney can do a Kim Possible experience at Epcot, how about Mattel’s American Girl making an Alternate Reality offering in each of the physical places (and past times) in which the stories of all of its historical dolls are set? Recognize, too, that you don’t have to make toys to have playful products—think of all of Apple’s offerings—and perhaps many B2B goods qualify as great bases for this realm, too, ranging from personal computers to construction equipment (such as at the Case Tomahawk Experience Center mentioned in Chapter 2).29

∞ If you already use (or develop) Augmented Reality offerings, figure out how to manipulate time to shift from Augmented to Alternate Reality. This might include looking to the future or past, nonlinear narratives, and random or unconstrained access to content.

∞ Look to mobile technology—cellphones, GPS sensors, cameras, compasses, accelerometers, and so forth—as the means to get customers out into the real world. Geocaching and geoteaming have already been innovated; what other “geo-activity” might you come up with?

∞ One commonality among all Alternate Reality offerings: get people up and active in the real world. It’s a great way to get people to exercise their bodies while exerting their minds.

∞ Another commonality at least most share: help people learn about the greater world around them.30 What value can you create by helping customers learn about your offerings, about societal issues, history, places, and subjects, or even about themselves? An alternate view of reality can in fact make that reality more accessible.

∞ Finally, apply this realm internally, just as McGonigal suggests, to your strategy or innovation process, and even to education and employee development. Over the long term, that could be one of the most impactful ways of creating value for your company.

So, here, think of all the lively ways you can apply Alternate Reality, but recognize its potential for serious play and learning, including for strategy and innovation, even for transformation. So how can you get your customers out in the real world, in your place or their place or public places, in ways that they value?